Dilmun

| Location | Eastern Arabia |

|---|---|

| Region | Northern Governorate |

| Type | Ancient |

| Part of | Eastern Arabia |

| History | |

| Founded | circa late 4th millennium BC[1] |

| Abandoned | c. 538 BC |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

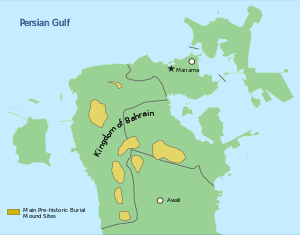

Dilmun, or Telmun,[2] (Arabic: دلمون, Sumerian: 𒆠, ni.tukki = DILMUNki;) was an ancient Semitic-speaking polity in Arabia mentioned from the 3rd millennium BC onwards.[3][4] Based on textual evidence, it was located in the Persian Gulf, on a trade route between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley Civilisation, close to the sea and to artesian springs.[1][5] A number of scholars have suggested that Dilmun originally designated the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, notably linked with the major Dilmunite settlements of Umm an-Nussi and Umm ar-Ramadh in the interior and Tarout on the coast.[6] Dilmun encompassed Bahrain, Kuwait,[7] Qatar and the eastern portion regions of Saudi Arabia.[8] This area is certainly what is meant by references to "Dilmun" among the lands conquered by King Sargon of Akkad and his descendants.

The great commercial and trading connections between Mesopotamia and Dilmun were strong and profound to the point where Dilmun was a central figure to the Sumerian creation myth.[9] Dilmun was described in the saga of Enki and Ninhursag as pre-existing in paradisiacal state, where predators don't kill, pain and diseases are absent, and people don't get old.[10]

Dilmun was an important trading centre. At the height of its power, it controlled the Persian Gulf trading routes.[1] According to some modern theories, the Sumerians regarded Dilmun as a sacred place,[11] but that is never stated in any known ancient text. Dilmun was mentioned by the Mesopotamians as a trade partner, a source of copper, and a trade entrepôt.

The Sumerian tale of the garden paradise of Dilmun may have been an inspiration for the Garden of Eden story.[12][13][14]

History

Dilmun was an important trading center from the late fourth millennium to 800 BC.[1] At the height of its power, Dilmun controlled the Persian Gulf trading routes.[1] Dilmun was very prosperous during the first 300 years of the second millennium.[15] Dilmun's commercial power began to decline between 1000 BC and 800 BC because piracy flourished in the Persian Gulf. In 600 BC, the Neo-Babylonian Empire, and later the Persian Empire, ruled Dilmun.

The Dilmun civilization was the centre of commercial activities linking traditional agriculture of the land—then utterly fertile due to artesian wells that have dried since, and due to a much wetter climate—with maritime trade between diverse regions such as the Meluhha (Indus River Valley), Magan (Oman), and Mesopotamia.[4] The Dilmun civilization is mentioned first in Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets dated to the late third millennium BC, found in the temple of goddess Inanna, in the city of Uruk. The adjective Dilmun is used to describe a type of axe and one specific official; in addition there are lists of rations of wool issued to people connected with Dilmun.[16]

One of the earliest inscriptions mentioning Dilmun is that of king Ur-Nanshe of Lagash (c. 2300 BC) found in a door-socket: "The ships of Dilmun brought him wood as tribute from foreign lands."[17]

From about 1700 BC come three inscriptions on stone vessels naming two kings of Dilmun. King Yagli-El and his father Rimum. The inscriptions were found in huge tumuli evidently the burial places of these kings. Rimum was already known to archaeology from the Durand Stone, discovered in 1879.[18]

Dilmun was mentioned in two letters dated to the reign of Burna-Buriash II (c. 1370 BC) recovered from Nippur, during the Kassite dynasty of Babylon. These letters were from a provincial official, Ilī-ippašra, in Dilmun to his friend Enlil-kidinni, the governor of Nippur. The names referred to are Akkadian. These letters and other documents, hint at an administrative relationship between Dilmun and Babylon at that time. Following the collapse of the Kassite dynasty, Mesopotamian documents make no mention of Dilmun with the exception of Assyrian inscriptions dated to 1250 BC which proclaimed the Assyrian king to be king of Dilmun and Meluhha, as well as Lower Sea and Upper Sea. Assyrian inscriptions recorded tribute from Dilmun.

There are other Assyrian inscriptions during the first millennium BC indicating Assyrian sovereignty over Dilmun.[19] One of the early sites discovered in Bahrain suggests that Sennacherib, king of Assyria (707–681 BC), attacked northeast Arabia and captured the Bahraini islands.[20] The most recent reference to Dilmun came during the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Neo-Babylonian administrative records, dated 567 BC, stated that Dilmun was controlled by the king of Babylon. The name of Dilmun fell from use after the collapse of Babylon in 538 BC.[19]

The "Persian Gulf" types of circular, stamped (rather than rolled) seals known from Dilmun, that appear at Lothal in Gujarat, India, and Failaka, as well as in Mesopotamia, are convincing corroboration of the long-distance sea trade. What the commerce consisted of is less known: timber and precious woods, ivory, lapis lazuli, gold, and luxury goods such as carnelian and glazed stone beads, pearls from the Persian Gulf, shell and bone inlays, were among the goods sent to Mesopotamia in exchange for silver, tin, woolen textiles, olive oil and grains.

Copper ingots from Oman and bitumen which occurred naturally in Mesopotamia may have been exchanged for cotton textiles and domestic fowl, major products of the Indus region that are not native to Mesopotamia. Instances of all of these trade goods have been found. The importance of this trade is shown by the fact that the weights and measures used at Dilmun were in fact identical to those used by the Indus, and were not those used in Southern Mesopotamia.

In regard to copper mining and smelting, the Umm al-Nar Culture and Dalma in the United Arab Emirates, and Ibri in Oman were particularly important.[21]

Some Meluhhan vessels may have sailed directly to Mesopotamian ports, but by the Isin-Larsa Period, Dilmun monopolized the trade. The Bahrain National Museum assesses that its "Golden Age" lasted ca. 2200–1600 BC. Discoveries of ruins under the Persian Gulf may be of Dilmun.[22]

People, language and religion

The population was Semitic with an Amorite presence; they used the Sumerian cuneiform,[23] and spoke a language that was either an Akkadian dialect, close to it or greatly influenced by it.[24][25] Dilmun's main deity was named Inzak and his spouse was Panipa.[26]

Mythology

In the early epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, the main events, which center on Enmerkar's construction of the ziggurats in Uruk and Eridu, are described as taking place at a time "before Dilmun had yet been settled".

Dilmun, sometimes described as "the place where the sun rises" and "the Land of the Living", is the scene of some versions of the Sumerian creation myth, and the place where the deified Sumerian hero of the flood, Utnapishtim (Ziusudra), was taken by the gods to live forever. Thorkild Jacobsen's translation of the Eridu Genesis calls it "Mount Dilmun" which he locates as a "faraway, half-mythical place".[27]

Dilmun is also described in the epic story of Enki and Ninhursag as the site at which the Creation occurred.[13][28] The later Babylonian Enuma Elish, speaks of the creation site as the place where the mixture of salt water, personified as Tiamat met and mingled with the fresh water of Abzu. Bahrein in Arabic means "the twin waters", where the fresh water of the Arabian aquifer mingles with the salt waters of the Persian Gulf. The promise of Enki to Ninhursag, the Earth Mother:

For Dilmun, the land of my lady's heart, I will create long waterways, rivers and canals, whereby water will flow to quench the thirst of all beings and bring abundance to all that lives.

Ninlil, the Sumerian goddess of air and south wind had her home in Dilmun.

However, it is also speculated that Gilgamesh had to pass through Mount Mashu to reach Dilmun in the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is usually identified with the whole of the parallel Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon ranges, with the narrow gap between these mountains constituting the tunnel.[29]

Location

In 1987, Theresa Howard-Carter proposed that Dilmun of this era might be a still unidentified tell near the Arvand Rud (Shatt al-Arab in Arabic) between modern-day Qurnah and Basra in modern-day Iraq.[30] In favor of Howard-Carter's proposal, it has been noted that this area does lie to the east of Sumer ("where the sun rises"), and the riverbank where Dilmun's maidens would have been accosted aligns with the Shat al-Arab which is in the midst of marshes. The "mouth of the rivers" where Dilmun was said to lie is for her the union of the Tigris and Euphrates at Qurnah.

As of 2008, archaeologists have failed to find a site in existence during the time from 3300 BC (Uruk IV) to 556 BC (Neo-Babylonian Era), when Dilmun appears in texts. According to Hojlund, no settlements exist in the Gulf littoral dating to 3300–2000 BC.

Garden of Eden theory

In 1922, Eduard Glaser proposed that the Garden of Eden was located in Eastern Arabia within the Dilmun civilization.[31] Scholar Juris Zarins also believes that the Garden of Eden was situated in Dilmun at the head of the Persian Gulf, where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers run into the sea, from his research on this area using information from many different sources, including Landsat images from space. In this theory, the Bible’s Gihon would correspond with the Karun in Iran, and the Pishon River would correspond to the Wadi Batin river system that once drained the now dry, but once quite fertile central part of the Arabian Peninsula.[32]

See also

- Dilmun Burial Mounds

- Gerrha

- History of Bahrain

- History of Iraq

- DHL International Aviation ME, a cargo airline using “Dilmun” as radio call sign

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jesper Eidema, Flemming Højlundb (1993). "Trade or diplomacy? Assyria and Dilmun in the eighteenth century BC". World Archaeology. 24 (3): 441–448. doi:10.1080/00438243.1993.9980218.

- ↑ The former is the reconstructed Sumerian pronunciation; the latter is the reconstructed Semitic.

- ↑ "Bahrain digs unveil one of oldest civilizations". BBC.

- 1 2 "Qal'at al-Bahrain – Ancient Harbour and Capital of Dilmun". UNESCO. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ "Dilmun and Its Gulf Neighbors". Harriet E. W. Crawford. 1998. p. 9.

- ↑ Roads of Arabia p.180

- ↑ "The Invention of Cuneiform: Writing in Sumer". Jean-Jacques Glassner. 1990. p. 7.

- ↑ "Prehistory and Protohistory of the Arabian Peninsula: Bahrain". M. A. Nayeem. 1990. p. 32.

- ↑ The Arab world: an illustrated history p.4

- ↑ The Arab world: an illustrated history p.4

- ↑ Rice, Michael (2004). Egypt's Making: The Origins of Ancient Egypt 5000-2000 BC. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-49263-3. , page 230

- ↑ Edward Conklin. Getting Back Into the Garden of Eden. p. 10.

- 1 2 Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 54–59. ISBN 0-8122-1047-6. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ↑ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 145–150. ISBN 0-226-45238-7.

In fact, there is some reason to believe that the very idea of a paradise, a garden of the gods, originated with the Sumerians.

- ↑ "Dilmun and Its Gulf Neighbours". Harriet E. W. Crawford. 1998. p. 152.

- ↑ Crawford, Harriet E. W. (1998). Dilmun and its Gulf neighbours. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-521-58348-9.

- ↑ Samuel Noah Kramer (1963). The Sumerians: their history, culture, and character. p. 308.

- ↑ Steffen Terp Laursen: Kings of Dilmun identified by name; Kings of Dilmun identified by name and announced in a press conference held by BACA

- 1 2 Larson, Curtis E. (1983). Life and land use on the Bahrain Islands: The geoarcheology of an ancient society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0-226-46905-0.

- ↑ Mojtahed-Zadeh, Pirouz (1999). Security and Territoriality in the Persian Gulf: A Maritime Political Geography. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-1098-1.

- ↑ "Egypt's Making: The Origins of Ancient Egypt 5000–2000 BC". Michael Rice. 1991. p. 229.

- ↑ The UK Register, Science, Lost ancient civilisation's ruins lie beneath Gulf, By Lewis Page Science, December 9, 2010

- ↑ William H. Stiebing Jr (2016). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. p. 217. ISBN 9781315511153.

- ↑ Jean Jacques Glassner (2013-10-28). "Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha". In Julian Reade. The Indian Ocean In Antiquity. p. 242. ISBN 9781136155314.

- ↑ Serge Cleuziou (1996). "The emergence of oasis towns in eastern and southern Arabia". In G. Afanas'ev; S. Cleuziou; R. Lukacs; M. Tosi. The prehistory of Asia and Oceania, Forlí: Colloquia of the XIII International congress of prehistoric and protohistoric sciences. 16. ABACO Edizioni, Forlì. p. 157. ISBN 978-88-86-71206-4.

- ↑ Jean Jacques Glassner (2013-10-28). "Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha". In Julian Reade. The Indian Ocean In Antiquity. p. 239. ISBN 9781136155314.

- ↑ Thorkild Jacobsen (23 September 1997). The Harps that once--: Sumerian poetry in translation. Yale University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-300-07278-5. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ↑ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 145–150. ISBN 0-226-45238-7.

- ↑ P. T. H. Unwin; Tim Unwin (18 June 1996). Wine and the Vine: An Historical Geography of Viticulture and the Wine Trade. Psychology Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-415-14416-2. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ Howard-Carter, Theresa (1987). "Dilmun: At Sea or Not at Sea? A Review Article". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 39 (1): 54–117. doi:10.2307/1359986. JSTOR 1359986.

- ↑ W. F. Albright (October 1922). "The Location of the Garden of Eden". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 39 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1086/369964. JSTOR 528684.

- ↑ Hamblin, Dora Jane (May 1987). "Has the Garden of Eden been located at last?" (PDF). Smithsonian Magazine. 18 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

External links

- Indus Valley—Mesopotamian trade passing through Dilmun

- Lost ancient civilisation's ruins lie beneath Gulf, says boffin

- Bahrain National Museum's hall of Dilmun

- Dilmun Site Al-Khidr, Failaka Island, State of Kuwait

- Greek inscriptions found on Bahrein (a pdf-file)

- Dilmun Calendar Theory Backed, Gulf Daily News, 11 July 2006