Susa

| شوش | |

Tepe of the Royal city (left) and of the Acropolis (right), seen from the Hill mound of the Apadana in Susa. | |

Shown within Iran | |

| Location | Shush, Khuzestan Province, Iran |

|---|---|

| Region | Zagros Mountains |

| Coordinates | 32°11′26″N 48°15′28″E / 32.19056°N 48.25778°ECoordinates: 32°11′26″N 48°15′28″E / 32.19056°N 48.25778°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | Approximately 4200 BCE |

| Abandoned | 1218 CE |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

| Official name | Susa |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 1455 |

| Inscription | 2015 (39th Session) |

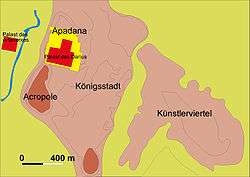

Susa (/ˈsuːsə/; Šuš; [ʃuʃ]; Hebrew: שׁוּשָׁן Šušān; Greek: Σοῦσα [ˈsuːsa]; Syriac: ܫܘܫ Šuš; Middle Persian: 𐭮𐭥𐭱𐭩 Sūš, 𐭱𐭥𐭮 Šūs; Old Persian Çūšā) was an ancient city of the Proto-Elamite, Elamite, First Persian Empire, Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian empires of Iran, and one of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East. It is located in the lower Zagros Mountains about 250 km (160 mi) east of the Tigris River, between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers. The site now "consists of three gigantic mounds, occupying an area of about one square kilometer, known as the Apadana mound, the Acropolis mound, and the Ville Royale (royal town) mound."[1]

The modern Iranian town of Shush is located at the site of ancient Susa. Shusha administrative capital of the Shush County of Iran's Khuzestan province. It had a population of 64,960 in 2005.[2]

Name

In Elamite, the name of the city was written variously Ŝuŝan, Ŝuŝun, etc. The origin of the word Susa is from the local city deity Inshushinak.

Literary references

Susa was one of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East. In historic literature, Susa appears in the very earliest Sumerian records: for example, it is described as one of the places obedient to Inanna, patron deity of Uruk, in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta.

Biblical texts

Susa is also mentioned in the Ketuvim of the Hebrew Bible by the name Shushan, mainly in Esther, but also once each in Nehemiah and Daniel. According to these texts, Nehemiah also lived in Susa during the Babylonian captivity of the 6th century BCE (Daniel mentions it in a prophetic vision), while Esther became queen there, married to King Ahasueurus, and saved the Jews from genocide. A tomb presumed to be that of Daniel is located in the area, known as Shush-Daniel. However, a large portion of the current structure is actually a much later construction dated to the late nineteenth century, ca. 1871.[3] Susa is further mentioned in the Book of Jubilees (8:21 & 9:2) as one of the places within the inheritance of Shem and his eldest son Elam; and in 8:1, "Susan" is also named as the son (or daughter, in some translations) of Elam.

Excavation history

The site was examined in 1836 by Henry Rawlinson and then by A. H. Layard.[4]

In 1851, some modest excavation was done by William Loftus, who identified it as Susa.[5]

In 1885 and 1886 Marcel-Auguste Dieulafoy and Jane Dieulafoy began the first French excavations.[6]

Jacques de Morgan conducted major excavations from 1897 until 1911. These efforts continued under Roland De Mecquenem until 1914, at the beginning of World War I. French work at Susa resumed after the war, led by De Mecquenem, continuing until World War II in 1940.[7][8][9] To supplement the original publications of De Mecquenem the archives of his excavation have now been put online thanks to a grant from the Shelby White Levy Program.[10][11]

Roman Ghirshman took over direction of the French efforts in 1946, after the end of the war. Together with his wife Tania Ghirshman, he continued there until 1967. The Ghirshmans concentrated on excavating a single part of the site, the hectare sized Ville Royale, taking it all the way down to bare earth.[12] The pottery found at the various levels enabled a stratigraphy to be developed for Susa.[13][14]

During the 1970s, excavations resumed under Jean Perrot.[15][16]

Early settlement

Archeologists have dated the first traces of an inhabited Neolithic village to c 7000 BCE. Evidence of a painted-pottery civilization has been dated to c 5000 BCE.[17] Painted ceramic vessels from Susa in the earliest first style are a late, regional version of the Mesopotamian Ubaid ceramic tradition that spread across the Near East during the fifth millennium BC.[18]

In urban history, Susa is one of the oldest-known settlements of the region. Based on C14 dating, the foundation of a settlement there occurred as early as 4395 BCE (a calibrated radio-carbon date).[19] At this stage it was already very large for the time, about 15 hectares.

The founding of Susa corresponded with the abandonment of nearby villages. Potts suggests that the settlement may have been founded to try to reestablish the previously destroyed settlement at Chogha Mish.[20] Previously, Chogha Mish was also a very large settlement, and it featured a similar massive platform that was later built at Susa.

Another important settlement in the area is Chogha Bonut, that was discovered in 1976.

Susa I period

Shortly after Susa was first settled over 6000 years ago, its inhabitants erected a monumental platform that rose over the flat surrounding landscape.[21] The exceptional nature of the site is still recognizable today in the artistry of the ceramic vessels that were placed as offerings in a thousand or more graves near the base of the temple platform.

Susa's earliest settlement is known as Susa I period (c. 4200–3900 BCE). Two settlements named by archeologists Acropolis (7 ha) and Apadana (6.3 ha), would later merge to form Susa proper (18 ha).[20] The Apadana was enclosed by 6m thick walls of rammed earth (this particular place is named Apadana because it also contains a late Achaemenid structure of this type).

Nearly two thousand pots of Susa I style were recovered from the cemetery, most of them now in the Louvre. The vessels found are eloquent testimony to the artistic and technical achievements of their makers, and they hold clues about the organization of the society that commissioned them.[18]

Susa I style was very much a product of the past and of influences from contemporary ceramic industries in the mountains of western Iran. The recurrence in close association of vessels of three types—a drinking goblet or beaker, a serving dish, and a small jar—implies the consumption of three types of food, apparently thought to be as necessary for life in the afterworld as it is in this one. Ceramics of these shapes, which were painted, constitute a large proportion of the vessels from the cemetery. Others are coarse cooking-type jars and bowls with simple bands painted on them and were probably the grave goods of the sites of humbler citizens as well as adolescents and, perhaps, children.[22] The pottery is carefully made by hand. Although a slow wheel may have been employed, the asymmetry of the vessels and the irregularity of the drawing of encircling lines and bands indicate that most of the work was done freehand.

Copper metallurgy is also attested during this period, which was contemporary with metalwork at some highland Iranian sites such as Tepe Sialk.

Susa II and Uruk influence

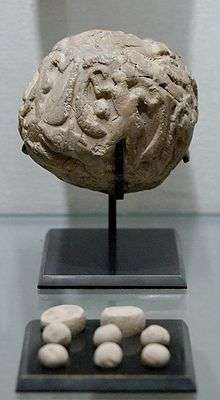

Susa came within the Uruk cultural sphere during the Uruk period. An imitation of the entire state apparatus of Uruk, proto-writing, cylinder seals with Sumerian motifs, and monumental architecture, is found at Susa. According to some scholars, Susa may have been a colony of Uruk.

There is some dispute about the comparative periodization of Susa and Uruk at this time, as well as about the extent of Uruk influence in Susa. Recent research indicates that Early Uruk period corresponds to Susa II period.[23]

D. T. Potts, argue that the influence from the highland Iranian Khuzestan area in Susa was more significant at the early period, and also continued later on. Thus, Susa combined the influence of two cultures, from the highland area and from the alluvial plains. Also, Potts stresses the fact that the writing and numerical systems of Uruk were not simply borrowed in Susa wholesale. Rather, only partial and selective borrowing took place, that was adapted to Susa's needs. Despite the fact that Uruk was far larger than Susa at the time, Susa was not its colony, but still maintained some independence for a long time, according to Potts.[24] An architectural link has also been suggested between Susa, Tal-i Malyan, and Godin Tepe at this time, in support of the idea of the parallel development of the protocuneiform and protoelamite scripts.[25]

Some scholars believe that Susa was part of the greater Uruk culture. Holly Pittman, an art historian at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia says, "they [Susanians] are participating entirely in an Uruk way of life. They are not culturally distinct; the material culture of Susa is a regional variation of that on the Mesopotamian plain". Gilbert Stein, director of the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute, says that "An expansion once thought to have lasted less than 200 years now apparently went on for 700 years. It is hard to think of any colonial system lasting that long. The spread of Uruk material is not evidence of Uruk domination; it could be local choice".[26]

Susa III period

Susa III (3100–2700 BCE) is also known as the 'Proto-Elamite' period.[27] At this time, Banesh period pottery is predominant. This is also when the Proto-Elamite tablets first appear in the record. Subsequently, Susa became the centre of Elam civilization.

Ambiguous reference to Elam (Cuneiform; 𒉏 NIM) appear also in this period in Sumerian records. Susa enters history during the Early Dynastic period of Sumer. A battle between Kish and Susa is recorded in 2700 BCE.

Elamites

In the Sumerian period, Susa was the capital of a state called Susiana (Šušan), which occupied approximately the same territory of modern Khūzestān Province centered on the Karun River. Control of Susiana shifted between Elam, Sumer, and Akkad. Susiana is sometimes mistaken as synonymous with Elam but, according to F. Vallat, it was a distinct cultural and political entity.[28]

Susiana was incorporated by Sargon the Great into his Akkadian Empire in approximately 2330 BCE.

Kutik-Inshushinak

Susa was the capital of an Akkadian province until ca. 2100 BCE, when its governor, Kutik-Inshushinak, rebelled and made it an independent state and a literary center. Also, he was the last from the Awan dynasty according to the Susa kinglist.[29] He unified the neighbouring territories and became the king of Elam. He encouraged the use of the Linear Elamite script, that remains undeciphered.

The city was subsequently conquered by the neo-Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur and held until Ur finally collapsed at the hands of the Elamites under Kindattu in ca. 2004 BCE. At this time, Susa became an Elamite capital under the Epartid dynasty.

Middle Elamite period

Around 1500 BCE, the Middle Elamite period began with the rise of the Anshanite dynasties. Their rule was characterized by an "Elamisation" of Susa, and the kings took the title "king of Anshan and Susa". While, previously, the Akkadian language was frequently used in inscriptions, the succeeding kings, such as the Igihalkid dynasty of c. 1400 BCE, tried to use Elamite. Thus, Elamite language and culture grew in importance in Susiana.[28]

This was also the period when the Elamite pantheon was being imposed in Susiana. This policy reached its height with the construction of the political and religious complex at Chogha Zanbil, 30 km (19 mi) south-east of Susa.

In ca. 1175 BCE, the Elamites under Shutruk-Nahhunte plundered the original stele bearing the Code of Hammurabi, the world's first known written laws,[30] and took it to Susa. Archeologists found it in 1901. Nebuchadnezzar I of the Babylonian empire plundered Susa around fifty years later.

Neo-Assyrians

In 647 BCE, Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal leveled the city during a war in which the people of Susa participated on the other side. A tablet unearthed in 1854 by Austen Henry Layard in Nineveh reveals Ashurbanipal as an "avenger", seeking retribution for the humiliations that the Elamites had inflicted on the Mesopotamians over the centuries:

"Susa, the great holy city, abode of their gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed. . . .I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones toward the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam and, on their lands, I sowed salt."[31]

Assyrian rule of Susa began in 647 BCE and lasted till Median capture of Susa in 617 BCE.

After Persian conquest

Achaemenid period

Susa underwent a major political and ethnocultural transition when it became part of the Persian Achaemenid empire between 540 and 539 BCE when it was captured by Cyrus the Great during his conquest of Elam (Susiana), of which Susa was the capital.[32] The Nabonidus Chronicle records that, prior to the battle(s), Nabonidus had ordered cult statues from outlying Babylonian cities to be brought into the capital, suggesting that the conflict over Susa had begun possibly in the winter of 540 BCE.[33]

It is probable that Cyrus negotiated with the Babylonian generals to obtain a compromise on their part and therefore avoid an armed confrontation.[34] Nabonidus was staying in the city at the time and soon fled to the capital, Babylon, which he had not visited in years.[35] Cyrus' conquest of Susa and the rest of Babylonia commenced a fundamental shift, bringing Susa under Persian control for the first time.

Under Cyrus' son Cambyses II, Susa became a center of political power as one of 4 capitals of the Achaemenid Persian empire, while reducing the significance of Pasargadae as the capital of Persis. Following Cambyses' brief rule, Darius the Great began a major building program in Susa and Persepolis. During this time he describes his new capital in the DSf inscription:

"This palace which I built at Susa, from afar its ornamentation was brought. Downward the earth was dug, until I reached rock in the earth. When the excavation had been made, then rubble was packed down, some 40 cubits in depth, another part 20 cubits in depth. On that rubble the palace was constructed."[36] Susa continued as a winter capital and residence for Achaemenid kings succeeding Darius the Great, Xerxes I, and their successors.[37]

The city forms the setting of The Persians (472 BCE), an Athenian tragedy by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus that is the oldest surviving play in the history of theatre.

Events mentioned in the Old Testament book of Esther are said to have occurred in Susa during the Achaemenid period.

Macedonian, Parthian and Sassanid periods

.jpg)

Susa lost much of its importance when Alexander of Macedon (Alexander the Great) conquered it in 331 BCE and incorporated the first Persian Empire. The Susa weddings was arranged by Alexander in 324 BCE in Susa, where mass weddings took place between the Persians and the Macedonians.

Approximately one century after Alexander, Susa fell to the Seleucid Empire. After Seleucia, it was the biggest city under Seleucid control at the time. Susa used Charax Spasinou as its port. It retained a considerable amount of independence and retained its Greek city-state organization well into the ensuing Parthian period and seems to have gained independence under a dynasty whose kings bore the name of Kamnaskires in the 1st century CE. [38]

When the Parthian Empire gained its independence from the Seleucid Empire, and took control of much of its eastern provinces, Susa was made one of the two capitals (along with Ctesiphon) of the new state.

Susa became a frequent place of refuge for Parthian and later, the Persian Sassanid kings, as the Romans sacked Ctesiphon five different times between 116 and 297 AD (Susa was briefly captured only by Roman emperor Trajan in 116 CE and never again would the Roman Empire advance so far to the east).[39] Typically, the Parthian rulers wintered in Susa, and spent the summer in Ctesiphon.

Post-Islamic period and degradation

Susa was destroyed at least three times in its history. The first was in 647 BCE, by Ashurbanipal. The second destruction took place in 638 CE, when the Muslim armies first conquered Persia. In 1218, the city was razed by invading Mongols. The city further degraded in the 15th century when the majority of its population moved to Dezful and it remains as a small settlement today.[40]

Susa had a significant Christian population during the first millennium, and was a diocese of the Church of the East between the 5th and 13th centuries, in the metropolitan province of Beth Huzaye (Elam).

Gallery

- Letter in Greek of the Parthian king Artabanus III to the inhabitants of Susa in the 1st century CE (the city retained Greek institutions since the time of the Seleucid empire). Louvre Museum.

Glazed clay cup: Cup with rose petals, 8th–9th centuries

Glazed clay cup: Cup with rose petals, 8th–9th centuries Anthropoid sarcophagus

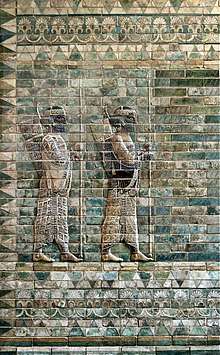

Anthropoid sarcophagus Lion on a decorative panel from Darius I the Great's palace

Lion on a decorative panel from Darius I the Great's palace%2C_late_1st_century_BC%E2%80%93early_1st_century_AD%2C_Louvre_Museum_(7462828632).jpg)

Glazed clay vase: Vase with palmtrees, 8th–9th centuries

Glazed clay vase: Vase with palmtrees, 8th–9th centuries Winged sphinx from the palace of Darius the Great at Susa.

Winged sphinx from the palace of Darius the Great at Susa. Ninhursag with the spirit of the forests next to the seven-spiked cosmic tree of life. Relief from Susa.

Ninhursag with the spirit of the forests next to the seven-spiked cosmic tree of life. Relief from Susa. 19th-century engraving of Daniel's tomb in Susa, from Voyage en Perse Moderne, by Flandin and Coste.

19th-century engraving of Daniel's tomb in Susa, from Voyage en Perse Moderne, by Flandin and Coste. Archers frieze from Darius' palace at Susa. Detail of the beginning of the frieze, left. Louvre Museum

Archers frieze from Darius' palace at Susa. Detail of the beginning of the frieze, left. Louvre Museum Ribbed torc with lion heads, Achaemenid artwork, excavated by Jacques de Morgan, 1901

Ribbed torc with lion heads, Achaemenid artwork, excavated by Jacques de Morgan, 1901- Shush Castle, 2011

- Children in Susa

Herm pillar with Hermes, from the well of the "Dungeon" in Susa.

Herm pillar with Hermes, from the well of the "Dungeon" in Susa.

See also

Notes

- ↑ John Curtis (2013). "Introduction". In Perrot, Jean. The Palace of Darius at Susa: The Great Royal Residence of Achaemenid Persia. I.B.Tauris. p. xvi. ISBN 9781848856219.

- ↑ "World city populations: Susa". Mongabay.com. 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2013-02-08.

- ↑ Kriwaczek, Paul. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization, St. Martin's Press, 2010, p. 5

- ↑ George Rawlinson, A Memoir of Major-General Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, Nabu Press, 2010, ISBN 1-178-20631-9

- ↑ Google Books, William K. Loftus, Travels and Researches in Chaldaea and Susiana, Travels and Researches in Chaldaea and Susiana: With an Account of Excavations at Warka, the "Erech" of Nimrod, and Shush, "Shushan the Palace" of Esther, in 1849-52, Robert Carter & Brothers, 1857

- ↑ Jane Dieulafoy, Perzië, Chaldea en Susiane. (in Dutch)

- ↑ Archive.org, Jacques de Morgan, Fouilles à Suse en 1897–1898 et 1898–1899, Mission archéologique en Iran, Mémoires I, 1990

- ↑ Archive.org, Jacques de Morgan, Fouilles à Suse en 1899–1902, Mission archéologique en Iran, Mémoires VII, 1905

- ↑ Robert H. Dyson, Early Work on the Acropolis at Susa. The Beginning of Prehistory in Iraq and Iran, Expedition, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 21-34, 1968

- ↑ Roland de Mecquenem: Archives de Suse (1912-1939) - in French

- ↑ Harvard.edu Archived 11 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Shelby White - Leon Levy Program funded project to publish early Susa archaeological results

- ↑ Roman Ghirshman, Suse au tournant du III au II millenaire avant notre ere, Arts Asiatiques, vol. 17, pp. 3-44, 1968

- ↑ Hermann Gasche, Ville Royal de Suse: vol I : La poterie elamite du deuxieme millenaire a.C, Mission archéologique en Iran, Mémoires 47, 1973

- ↑ M. Steve and Hermann H. Gasche, L'Acropole de Suse: Nouvelles fouilles (rapport preliminaire), Memoires de la Delegation archeologique en Iran, vol. 46, Geuthner, 1971

- ↑ Jean Perrot, Les fouilles de Sus en 1975, Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran 4, pp. 224-231, 1975

- ↑ D. Canal, La haute terrase de l'Acropole de Suse, Paleorient, vol. 4, pp. 169-176, 1978

- ↑ Langer, William L., ed. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 17. ISBN 0-395-13592-3.

- 1 2 Aruz, Joan (1992). The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. New York: Abrams. p. 26.

- ↑ The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State - by D. T. Potts, Cambridge University Press, 29/07/1999 - page 46 - ISBN 0521563585 hardback

- 1 2 Potts, 1999

- ↑ Hole, Frank. “A Monumental Failure: The Collapse of Susa.” In Robin A. Carter and Graham Philip, eds., Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration of Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East, pp. 221–226, Studies in Oriental Civilization, no. 63, Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2010

- ↑ Aruz, Joan (1992). The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. New York: Abrams. p. 29.

- ↑ D. T. Potts, The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, 2015 ISBN 1107094690 p58

- ↑ D. T. Potts, The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, 2015 ISBN 1107094690 pp 58-61

- ↑ F. Desset, An Architectural Pattern in Late Fourth-Millennium BC Western Iran: A New Link Between Susa, Tal-I Malyan, and Godin Tepe, Iran, vol. 52, iss. 1, pp. 1-18, 2014

- ↑ Lawler, Andrew. 2003. Uruk: Spreading Fashion or Empire. Science. Volume 302, P. 977-978

- ↑ D. T. Potts, A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Volume 94 of Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons, 2012 ISBN 1405189886 p743

- 1 2 F. Vallat, The history of Elam, 1999 iranicaonline.org

- ↑ Daniel T. Potts, The Archaeology of Elam. Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 122

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ "Persians: Masters of Empire" ISBN 0-8094-9104-4 p. 7-8

- ↑ Tavernier, Jan. "Some Thoughts in Neo-Elamite Chronology" (PDF). p. 27.

- ↑ Kuhrt, Amélie. "Babylonia from Cyrus to Xerxes", in The Cambridge Ancient History: Vol IV — Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean, pp. 112–138. Ed. John Boardman. Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-521-22804-2

- ↑ Tolini, Gauthier, Quelques éléments concernant la prise de Babylone par Cyrus, Paris. "Il est probable que des négociations s’engagèrent alors entre Cyrus et les chefs de l’armée babylonienne pour obtenir une reddition sans recourir à l’affrontement armé." p. 10 (PDF)

- ↑ The Harran Stelae H2 - A, and the Nabonidus Chronicle (Seventeenth year) show that Nabonidus had been in Babylon before 10 October 539, because he had already returned from Harran and had participated in the Akitu of Nissanu 1 [4 April], 539 BCE.

- ↑ Lendering, 2010

- ↑ "Susa: Statue of Darius". Livius.org. 2009-04-01. Retrieved 2013-02-08.

- ↑ John E. Hill, Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE, BookSurge, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1

- ↑ Robert J. Wenke, Elymeans, Parthians, and the Evolution of Empires in Southwestern Iran, Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 101, no. 3, pp. 303-315, 1981

- ↑ M. Streck, Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1997). Encyclopaedia of Islam, San-Sze. IX. Leiden: Brill. pp. 898–899. ISBN 9789004104228.

- ↑ Jonsson, David J. (2005). The Clash of Ideologies. Xulon Press. p. 566. ISBN 978-1-59781-039-5.

Antiochus III was born in 242 BC, the son of Seleucus II, near Susa, Iran.

References

- Jean Perrot, Le Palais de Darius à Suse. Une résidence royale sur la route de Persépolis à Babylone, Paris, Paris-sorbonne.fr, 2010

- Lendering, Jona. "Susa, capital of Elam". The Iranian Chamber. Retrieved 2010. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Vallat, François (1999). "The History of Elam". The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies (CAIS).

- Potts, Daniel T. (1999). The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian state. Cambridge University Press, 1999. p. 490. ISBN 0-521-56496-4. World Archaeology Series.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Susa. |

- "Early Works on the Acropolis at Susa" Expedition Magazine 10.4 1968

- Livius.org pictures of Susa

- Aerial views of Susa at the Oriental Institute

- Digital Images of Cuneiform Tablets from Susa - CDLI

- Hamid-Reza Hosseini, Shush at the foot of Louvre (Shush dar dāman-e Louvre), in Persian, Jadid Online, 10 March 2009.

- Audio slideshow at Jadidonline.com (6 min 31 sec)