Lebanese Arabic

| Lebanese Arabic | |

|---|---|

| اللهجة اللبنانية | |

| Native to | Lebanon |

Native speakers | 5.47 million (2015)[1] |

| Dialects | |

|

Arabic alphabet Arabic chat alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

apc |

| ISO 639-3 |

apc |

| Glottolog |

stan1323[2] |

North Lebanese Arabic

North-Central Lebanese Arabic

Beqaa Arabic

Jdaideh Arabic

Sunni Beiruti Arabic

South-Central Lebanese Arabic

Iqlim-Al-Kharrub Sunni Arabic

Saida Sunni Arabic

South Lebanese Arabic | |

Lebanese Arabic or Lebanese is a variety of North Levantine Arabic, indigenous to and spoken primarily in Lebanon, with significant linguistic influences borrowed from other Middle Eastern and European languages, and is in some ways unique from other varieties of Arabic. Due to multilingualism among Lebanese people (a majority of the Lebanese people are bilingual or trilingual - speaking Arabic, French, and/or English), it is not uncommon for Lebanese people to mix Lebanese Arabic, French, and English languages into their daily speech.

Differences from Standard Arabic

Lebanese Arabic shares many features with other modern varieties of Arabic. Lebanese Arabic, like many other spoken Levantine Arabic varieties, has a syllable structure very different from that of Modern Standard Arabic. While Standard Arabic can have only one consonant at the beginning of a syllable, after which a vowel must follow, Lebanese Arabic commonly has two consonants in the onset.

- Morphology: simpler, without any mood and case markings.

- Number: verbal agreement regarding number and gender is required for all subjects, whether already mentioned or not.

- Vocabulary: many borrowings from other languages; most prominently Syriac-Aramaic, Western-Aramaic, Phoenician-Ugaritic, Ottoman Turkish, French , as well as, less significantly, from English.

- About 50 percent of the Lebanese grammatical structure is due to Aramaic influences.[3]

Examples

- The following example demonstrates two differences between Standard Arabic (Literary Arabic) and Spoken Lebanese Arabic: Coffee (قهوة), Literary Arabic: /ˈqahwa/; Lebanese Arabic: [ˈʔahwe]. The voiceless uvular plosive /q/ corresponds to a glottal stop [ʔ], and the final vowel ([æ~a~ɐ]) commonly written with tāʾ marbūtah (ة) is raised to [e].

- As a general rule of thumb, the voiceless uvular plosive /q/ is replaced with glottal stop [ʔ], e.g. /daqiːqa/ "minute" becomes [dʔiːʔa]. This debuccalization of /q/ is a feature shared with Syrian Arabic, Palestinian Arabic, Egyptian Arabic, and Maltese.

- The exception for this general rule is the Druze of Lebanon who, like the Druze of Syria and Israel, have retained the pronunciation of /q/ in the centre of direct neighbours who have substituted the /q/ for the [ʔ] (example: "Heart" is /qalb/ in Literary Arabic, becomes [ˈʔaleb] or [ʔalb], which is similar in Syrian, Palestinian, Egyptian and Maltese. The use of /q/ by Druze is particularly prominent in the mountains and less so in urban areas.

- Unlike most other varieties of Arabic, a few dialects of Lebanese Arabic have retained the classical diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/ (pronounced in Lebanese Arabic as [aɪ] and [aʊ]), which were monophthongised into [eː] and [oː] elsewhere, although the majority of Lebanese Arabic dialects realize them as [oʊ] and [eɪ]. In urban dialects (i.e. Beiruti) [eː] has replaced /aj/ and sometimes medial /aː/, and [e] has replaced final /i/ making it indistinguishable with tāʾ marbūtah (ة). Also, [oː] has replaced /aw/; [o] replacing some short /u/s. In singing, the /aj/, /aw/ and medial /aː/ are usually maintained for artistic values.

- /t/ and /θ/ are both pronounced [t].

Not Arabic?

Several commentators, including Nassim Taleb, have claimed that the Lebanese vernacular is not in fact a variety of Arabic at all, but rather a separate Central Semitic languages, descended from Aramaic with the many Arabic and Turkish loanwords and use of the Arabic alphabet disguising the language's true nature.[4] Taleb recommended that the language be called Northwestern Levantine or neo-Canaanite.[5][6][7] This classification is not widely accepted by linguists.[8][9][10]

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar/ Uvular |

Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | |||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||

| Stop | voiceless | (p) | t | tˤ | k | ʔ | ||

| voiced | b | d | dˤ | (ɡ) | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | sˤ | ʃ (t͡ʃ) | x | ħ | h |

| voiced | (v) | z | zˤ | ʒ | ɣ | ʕ | ||

| Tap/trill | r | |||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||

- The phonemes /p, v/ are not native to Lebanese Arabic and are only found in loanwords. They are sometimes realized as [b] and [f] respectively.

- The velar stop /g/ occurs in native Lebanese Arabic words but is generally restricted to loanwords. It is realized as [k] by some speakers.

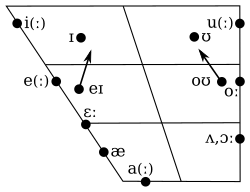

Vowels and diphthongs

Comparison

This table shows the correspondence between general Lebanese Arabic vowel phonemes and their counterpart realizations in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and other Levantine Arabic varieties.

| Lebanese Arabic | MSA | Southern | Central | Northern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /æ/ | [a] | [ɑ] or [ʌ] | [ɑ] or [ʌ] | [ɔ] or [ɛ] |

| /ɪ/ | [i] or [u] | [e] | [ə] | [e] or [o] |

| /ʊ/ | [u] | [o] or [ʊ] | [o] | [o] |

| /e/1 | [a] | [e]1 | [e]1 | [e]1 |

| /ɛ:/ | [a:] | [a:] | [æ:] | [e:] |

| /ɔ:/ | [a:] | [a:] | [ɑ:] | [o:] |

| /e:/ | [a:] | [a] | [e] | [e] |

| /i/: | [i:] | [i:] | [i:] | [i:] |

| /i~e/ | [i:] | [i] | [i] | [i] |

| /u:/ | [u:] | [u:] | [u:] | [u:] |

| /eɪ~e:/ | [aj] | [e:] | [e:] | [e:] |

| /oʊ~o:/ | [aw] | [o:] | [o:] | [o:] |

^1 After back consonants this is pronounced [ʌ] in Lebanese Arabic, Central and Northern Levantine varieties, and as [ɑ] in Southern Levantine varieties

Regional varieties

Although there is a common Lebanese Arabic dialect mutually understood by Lebanese people, there are regionally distinct variations with, at times, unique pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary. [12]

Widely used regional varieties include:

- Beiruti varieties, further distributed according to neighborhoods, the notable ones being Achrafieh variety, Basta variety, Ras Beirut variety, etc.

- Northern varieties, further distributed regionally, the most notable ones being Tripoli variety, Zgharta variety, Bsharri variety, Koura variety, Akkar variety.

- Southern varieties, with notable ones being the Tyre and Bint Jbeil varieties.

- Beqaa varieties, further divided into varieties, the notable ones being Zahlé and Baalbek-Hermel varieties.

- Mount Lebanon varieties, further divided into regional varieties like the Keserwan variety, the Matin dialect, Shouf variety, etc.

Writing system

Lebanese Arabic is rarely written, except in novels where a dialect is implied or in some types of poetry that do not use classical Arabic at all. Lebanese Arabic is also utilized in many Lebanese songs, theatrical pieces, local television and radio productions, and very prominently in zajal.

Formal publications in Lebanon, such as newspapers, are typically written in Modern Standard Arabic, French, or English.

While Arabic script is usually employed, informal usage such as online chat may mix and match Latin letter transliterations. The Lebanese poet Saïd Akl proposed the use of the Latin alphabet but did not gain wide acceptance. Whereas some works, such as Romeo and Juliet and Plato's Dialogues have been transliterated using such systems, they have not gained widespread acceptance. Yet, now, most Arabic web users, when short of an Arabic keyboard, transliterate the Lebanese Arabic words in the Latin alphabet in a pattern similar to the Said Akl alphabet, the only difference being the use of digits to render the Arabic letters with no obvious equivalent in the Latin alphabet.

There is still today no generally accepted agreement on how to use the Latin alphabet to transliterate Lebanese Arabic words. However, Lebanese people are now using latin numbers while communicating online to make up for sounds not directly associable to latin letters: for example, the character 7 is equivalent to a deep H sound. In 2010, The Lebanese Language Institute has released a Lebanese Arabic keyboard layout and made it easier to write Lebanese Arabic in a Latin script, using unicode-compatible symbols to substitute for missing sounds.[13]

Said Akl's orthography

- Capitalization and punctuation are used normally the same way they are used in the French and English languages.

- Some written consonant-letters, depending on their position, inherited a preceding vowel. As L and T.

- Emphatic consonants are not distinguished from normal ones, with the exception of /zˤ/ represented by ƶ. Probably Said Akl did not acknowledge any other emphatic consonant.

- Stress is not marked.

- Long vowels and geminated consonants are represented by double letters.

- Ç which represents /ʔ/ was written even initially.

- All the basic Latin alphabet are used, in addition to other diacriticized ones. Most of the letters loosely represent their IPA counterparts, with some exceptions:

| Letter | Corresponding phoneme(s) | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

| a | /a/, /ɑ/ | |

| aa | /aː/, /ɑː/ | |

| c | /ʃ/ | |

| ç | /ʔ/ | The actual diacritic looks like a diagonal stroke on the bottom left |

| g | /ɣ/ | |

| i | /ɪ/, /i/ | Represents /i/ word-finally |

| ii | /iː/ | |

| j | /ʒ/ | |

| k | /χ/ | |

| q | /k/ | |

| u | /ʊ/, /u/ | Represents /u/ word-finally |

| uu | /uː/ | |

| x | /ħ/ | |

| y | /j/ | |

| ȳ | /ʕ/ | The actual diacritic looks like a stroke connected to the upper-left spoke of the letter |

| ƶ | /zˤ/ |

See also

References

- ↑ "Arabic, North Levantine Spoken". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Lebanese Arabic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "You may think you're speaking Lebanese, but some of your words are really Syriac". The Daily Star Newspaper - Lebanon. 2008-11-25. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ↑ Taleb, Nassim Nicholas (2 January 2018). "No, Lebanese is not a "dialect of" Arabic".

- ↑ https://www.maronite-heritage.com/Lebanese%20Language.php

- ↑ "Phoenicia: The Lebanese Language: What is the difference between the Arabic Language and the Lebanese language?". phoenicia.org.

- ↑ "Lebanese Language Institute » History". www.lebaneselanguage.org.

- ↑ سواق, Lameen Souag الأمين (4 January 2018). "Jabal al-Lughat: Taleb unintentionally proves Lebanese comes from Arabic".

- ↑ "Lebanese and Arabic - A Post-Mortem of the Nassim Taleb kerfuffle". Twitter.

- ↑ "How well does Nassim Taleb's evidence hold up in his piece arguing against the idea that the direct ancestor of Lebanese is not an old form of Arabic and should not be referred to as an Arabic dialect? - Quora". www.quora.com.

- ↑ Abdul-Karim, K. 1979. Aspects of the Phonology of Lebanese Arabic. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Doctoral Dissertation.

- ↑ Makki, Elrabih Massoud. 1983. The Lebanese dialect of Arabic: Southern Region. (Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University; 155pp.)

- ↑ Lebanese Language Institute: Lebanese Latin Letters The Lebanese Latin Letters

Bibliography

- Spoken Lebanese. Maksoud N. Feghali, Appalachian State University. Parkway Publishers, 1999 ( ISBN 978-1-887905-14-5)

- Michel T. Feghali, Syntaxe des parlers arabes actuels du Liban, Geuthner, Paris, 1928.

- Elie Kallas, 'Atabi Lebnaaniyyi. Un livello soglia per l'apprendimento del neoarabo libanese, Cafoscarina, Venice, 1995.

- Angela Daiana Langone, Btesem ente lebneni. Commedia in dialetto libanese di Yahya Jaber, Università degli Studi La Sapienza, Rome, 2004.

- Jérome Lentin, "Classification et typologie des dialectes du Bilad al-Sham", in Matériaux Arabes et Sudarabiques n. 6, 1994, 11–43.

- Plonka Arkadiusz, L’idée de langue libanaise d’après Sa‘īd ‘Aql, Paris, Geuthner, 2004, ISBN 978-2-7053-3739-1

- Plonka Arkadiusz, "Le nationalisme linguistique au Liban autour de Sa‘īd ‘Aql et l’idée de langue libanaise dans la revue «Lebnaan» en nouvel alphabet", Arabica, 53 (4), 2006, 423–471.

- Franck Salameh, "Language, Memory, and Identity in the Middle East", Lexington Books, 2010.

- lebaneselanguage.org, "Lebanese vs Arabic", Lebanese Language Institute, March 6, 2010.

- Abdul-Karim, K. 1979. Aspects of the Phonology of Lebanese Arabic. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Doctoral Dissertation.

- Bishr, Kemal Mohamed Aly. 1956. A grammatical study of Lebanese Arabic. (Doctoral dissertation, University of London; 470pp.)

- Choueiri, Lina. 2002. Issues in the syntax of resumption: restrictive relatives in Lebanese Arabic. Ann Arbor: UMI. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Los Angeles; xi+376pp.)

- Makki, Elrabih Massoud. 1983. The Lebanese dialect of Arabic: Southern Region. (Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University; 155pp.)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lebanese Arabic phrasebook. |