Magna Graecia

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Italy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Greece |

|

|

History by topic |

|

|

Magna Graecia (/ˌmæɡnə

Antiquity

According to Strabo, Magna Graecia's colonization had already begun by the time of the Trojan War and lasted for several centuries.[2]

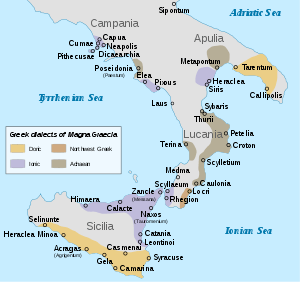

In the 8th and 7th centuries BC, for various reasons, including demographic crises (famine, overcrowding, etc.), the search for new commercial outlets and ports, and expulsion from their homeland, Greeks began to settle in southern Italy (Cerchiai, pp. 14–18). Also during that period, Greek colonies were established in places as widely separated as the eastern coast of the Black Sea, Eastern Libya and Massalia (Marseille). They included settlements in Sicily and the southern part of the Italian Peninsula. The Romans called the area of Sicily and the foot of Italy Magna Graecia (Latin, “Great Greece”) since it was so densely inhabited by the Greeks. The ancient geographers differed on whether the term included Sicily or merely Apulia and Calabria: Strabo being the most prominent advocate of the wider definitions.

With colonization, Greek culture was exported to Italy, in its dialects of the Ancient Greek language, its religious rites and its traditions of the independent polis. An original Hellenic civilization soon developed, later interacting with the native Italic civilisations. The most important cultural transplant was the Chalcidean/Cumaean variety of the Greek alphabet, which was adopted by the Etruscans; the Old Italic alphabet subsequently evolved into the Latin alphabet, which became the most widely used alphabet in the world.

Many of the new Hellenic cities became very rich and powerful, like Neapolis (Νεάπολις, Naples, "New City"), Syracuse (Συράκουσαι), Acragas (Ἀκράγας) Paestum (Ποσειδωνία) and Sybaris (Σύβαρις). Other cities in Magna Graecia included Tarentum (Τάρας), Epizephyrian Locri (Λοκροί Ἐπιζεφύριοι), Rhegium (Ῥήγιον), Croton (Κρότων), Thurii (Θούριοι), Elea (Ἐλέα), Nola (Νῶλα), Ancona (Ἀγκών), Syessa (Σύεσσα), Bari (Βάριον) and others.

Following the Pyrrhic War in the 3rd century BC, Magna Graecia was absorbed into the Roman Republic.

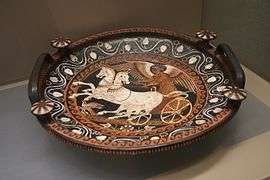

5th century BC Greek coins of Tarentum

5th century BC Greek coins of Tarentum

Middle Ages

During the Early Middle Ages, following the disastrous Gothic War, new waves of Byzantine Christian Greeks may have come to Southern Italy from Greece and Asia Minor, as Southern Italy remained loosely governed by the Eastern Roman Empire. Although possible, the archaeological evidence shows no trace of new arrivals of Greek peoples, only a division between barbarian newcomers, and Greco-Roman locals. The iconoclast emperor Leo III appropriated lands that had been granted to the Papacy in southern Italy[3] and the Eastern Emperor loosely governed the area until the advent of the Lombards then, in the form of the Catapanate of Italy, superseded by the Normans.

A remarkable example of the influence is the Griko-speaking minority that still exists today in the Italian regions of Calabria and Apulia. Griko is the name of a language combining ancient Doric, Byzantine Greek, and Italian elements, spoken by few people in some villages in the Province of Reggio Calabria and Salento. There is a rich oral tradition and Griko folklore, limited now but once numerous, to around 30,000 people, most of them having become absorbed into the surrounding Italian element. Some scholars, such as Gerhard Rohlfs, argue that the origins of Griko may ultimately be traced to the colonies of Magna Graecia.

Modern Italy

Although many of the Greek inhabitants of Southern Italy were entirely Italianized during the Middle Ages (for example, Paestum was by the 4th century BC), pockets of Greek culture and language remained and survived into modernity partly because of continuous migration between southern Italy and the Greek mainland. One example is the Griko people, some of whom still maintain their Greek language and customs.

Greeks re-entered the region in the 16th and 17th century in reaction to the conquest of the Peloponnese by the Ottoman Empire. Especially after the end of the Siege of Coron (1534), large numbers of Greeks took refuge in the areas of Calabria, Salento and Sicily. Greeks from Coroni, the so-called Coronians, were nobles, who brought with them substantial movable property. They were granted special privileges and tax exemptions.

Other Greeks who moved to Italy came from the Mani Peninsula of the Peloponnese. The Maniots were known for their proud military traditions and for their bloody vendettas, many of which still continue today. Another group of Maniot Greeks moved to Corsica.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, Paul Harvey, 1927,1955, p258

- ↑ [ Strabo, Geographica οἱ δὲ τῆς Σικελίας τύραννοι καὶ μετὰ ταῦτα Καρχηδόνιοι, τοτὲ μὲν περὶ τῆς Σικελίας πολεμοῦντες πρὸς Ῥωμαίους τοτὲ δὲ περὶ αὐτῆς τῆς Ἰταλίας, ἅπαν- τας τοὺς ταύτῃ κακῶς διέθηκαν, μάλιστα δὲ τοὺς Ἕλληνας, πρότερον μέν γε καὶ τῆς μεσογαίας πολλὴν ἀφῄρηντο, ἀπὸ τῶν Τρωικῶν χρόνων ἀρξάμενοι, καὶ δὴ ἐπὶ τοσοῦτον ηὔξηντο ὥστε τὴν μεγάλην Ἑλλάδα ταύτην ἔλεγον καὶ τὴν Σικελίαν· νυνὶ δὲ πλὴν Τάραντος καὶ Ῥηγίου καὶ Νεαπόλεως ἐκβεβαρβαρῶσθαι συμβέβηκεν ἅπαντα καὶ τὰ μὲν Λευκανοὺς καὶ Βρεττίους κατέχειν τὰ δὲ Καμπανούς, καὶ τούτους λόγῳ, τὸ δ' ἀληθὲς Ῥωμαίους· καὶ γὰρ αὐτοὶ Ῥωμαῖοι γεγόνασιν. ]

- ↑ T. S. Brown, "The Church of Ravenna and the Imperial Administration in the Seventh Century," The English Historical Review (1979 pp 1-28) p.5.

References

- Cerchiai L., Jannelli L., Longo F. The Greek Cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily. Getty Trust, 2004. ISBN 0-89236-751-2

- Dunbabin T. J. The Western Greeks. 1948.

- Smith W. "Magna Graecia." In Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. 1854.

- Woodhead A. G. The Greeks in the West. 1962.

Further reading

- Adam-Veleni, Polyxeni, and Dimitra Tsangari, eds. 2015. Greek colonisation: New data, current approaches; Proceedings of the scientific meeting held in Thessaloniki (6 February 2015). Athens: Alpha Bank.

- Bennett, Michael J., Aaron J. Paul, Mario Iozzo, and Bruce M. White. 2002. Magna Graecia: Greek Art From South Italy and Sicily. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art.

- Casadio, Giovanni, and Patricia A. Johnston. 2009. Mystic Cults In Magna Graecia. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Cerchiai, Lucia, Lorenna Jannelli, and Fausto Longo, eds. 2004. The Greek cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily. Photography by Mark E. Smith. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Ceserani, Giovanna. 2012. Italy's Lost Greece: Magna Graecia and the Making of Modern Archaeology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gualtieri, M. 1993. Fourth Century B.C. Magna Graecia: A Case Study. Jonsered, Sweden: P. Åströms.

- Holloway, R. Ross. 1978. Art and Coinage In Magna Graecia. Bellinzona: Edizioni arte e moneta.

- Mayo, Margaret Ellen. 1982. The Art of South Italy: Vases From Magna Graecia. Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

- Pugliese Carratelli, Giovanni. 1996. The Greek World: Art and Civilization In Magna Graecia and Sicily. New York: Rizzoli.

- ————, ed. 1996. The Western Greeks: Catalog of an exhibition held in the Palazzo Grassi, Venice, March–Dec., 1996. Milan: Bompiani.

- Zuntz, Günther. 1971. Persephone: Three Essays On Religion and Thought In Magna Graecia. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Magna Graecia. |

| Library resources about Magna Graecia |

- Map. Ancient Coins.

- David Willey. Italy rediscovers Greek heritage. BBC News. 21 June 2005, 17:19 GMT 18:19 UK.

- Gaze On The Sea. Salentine Peninsula, Greece and Greater Greece. (in Italian, Greek and English)

- Oriamu pisulina. Traditional Griko song performed by Ghetonia.

- Kalinifta. Traditional Griko song performed by amateur local group.

- Second Interdisciplinary Symposium on the Hellenic Heritage of Southern Italy. Archaeological Institute of America (AIA). June 11, 2015. (Dates: Monday, May 30, 2016 to Thursday, June 2, 2016.)

- Sergio Tofanelli et al. The Greeks in the West: genetic signatures of the Hellenic colonisation in southern Italy and Sicily. European Journal of Human Genetics, (15 July 2015).