Italian Civil War

| Italian Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Italian Campaign (World War II), World War II | |||||||

Italian Civil War scene. Partisan hanged by republican fascists of the Decima Flottiglia MAS. The sign says "He attempted with weapons to shoot the Decima". | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5,000+ killed 7,500+ missing 7,500+ wounded (June–August 1944 only) |

5,927 killed[7] unknown wounded, captured, and missing 35,828 killed 21,168 seriously wounded[8] unknown captured | ||||||

| ~80,506 civilians killed[9] | |||||||

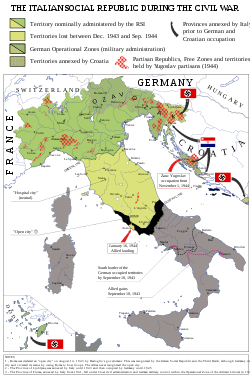

The Italian Civil War (Italian: La guerra civile) is the period between September 8, 1943 (the date of the armistice of Cassibile), and May 2, 1945 (the date of the surrender of German forces in Italy[10]) in which the Italian Resistance and the Italian Co-Belligerent Army joined the allies fighting Axis forces including continuing Italian Fascists Italian Social Republic.[11]

Terminology

Claudio Pavone's book Una guerra civile. Saggio storico sulla moralità della Resistenza (A Civil War. Historical Essay On the Morality Of the Resistance), published in 1991, led the term Italian Civil War to become a widespread term used in Italian[12] and international[13][14] historiography. Although the term had been used before,[15] in the early 1990s it became accepted.

Factions

The confrontations between the factions resulted in the torture and death of many civilians. During the Italian Campaign, partisans were supplied by the Western Allies with small arms, ammunition and explosives. Allied forces and partisans cooperated on military missions, parachuting or landing personnel behind enemy lines, often including Italian–American members of OSS. Other operations were carried out exclusively by secret service personnel. Where possible, both sides avoided situations in which Italian units of opposite fronts were involved in combat episodes. In rare cases, clashes between Italians involved partisans and fascists of various armed formations.

Partisans

The first groups of partisans were formed in Boves (Piedmont) and Bosco Martese (Abruzzo). Other groups composed mainly of Slavic and communist elements sprang up in Venezia Giulia. Others grew around Allied Yugoslav and Soviet prisoners of war, released or escaped from captivity following the events of September 8. These first organized units soon dissolved because of the rapid German reaction. In Boves, the Nazis committed their first massacre on Italian territory.

On September 8, hours after the radio communication of the armistice, several antifascist organizations converged on Rome. They were Ivanoe Bonomi (PDL), Scoccimarro and Amendola (PCI), De Gasperi (DC), La Malfa and Fenoaltea (PDA), Nenni and Romita (PSI), Ruini (DL), Casati (PLI). They formed the first Committee of National Liberation (CLN). Bonomi took over the presidency.[16]

The Italian Communist Party was anxious to take the initiative without waiting for the Allies:

(in Italian) ...è necessario agire subito ed il più ampiamente e decisamente possibile perché solo nella misura in cui il popolo italiano concorrerà attivamente alla cacciata dei tedeschi dall'Italia, alla sconfitta del nazismo e del fascismo, potrà veramente conquistarsi l'indipendenza e la libertà. Noi non possiamo e non dobbiamo attenderci passivamente la libertà dagli angloamericani. - [17]

"... It's necessary to act immediately and as widely and decisively as possible, because only if the Italian People actively contribute to push out Germans from Italy and to defeat Nazism and Fascism, it will be really able to get independence and freedom. We can not and must not passively expect freedom from the British and the Americans."

The Allies did not believe in the guerillas' effectiveness, so General Alexander postponed their attacks against the Nazis. On 16 October the CLN issued its first important political and operational press release,[18] which rejected the calls for reconciliation launched by Republican leaders. CLN Milan asked "the Italian people to fight against the German invaders and against their fascists lackeys".[19]

In late November, the Communists established task forces called distaccamenti d'assalto Garibaldi which later would become brigades and divisions[note 1] whose leadership was entrusted to Luigi Longo, under the political direction of Pietro Secchia and Giancarlo Pajetta, Chief of Staff. The first operational order dated 25 November ordered the partisans to:

- attack and annihilate in every way officers, soldiers, material, deposits of Hitler's armed forces;

- attack and annihilate in every way people, places, properties of fascists and traitors who collaborate with the occupying Germans;

- attack and annihilate in every way war industries, communication systems and everything that might help to war plans of Nazi occupants.[20]

Shortly after the Armistice, the Italian Communist Party,[21] the Gruppi di Azione Patriottica ("Patriotic Action Groups") or simply GAP, established small cells whose main purpose was to unleash urban terror through bomb attacks against fascists, Germans and their supporters. They operated independently in case of arrest or betrayal of individual elements. The success of these attacks led the German and Italian police to believe they were composed of foreign intelligence agents. A public announcement from the PCI in September 1943 stated:

To the tyranny of Nazism, that claims to reduce to slavery through violence and terror, we must respond with violence and terror.

— Appeal of PCI to the Italian People, September 1943

The GAP's mission was claimed to be delivering "justice" to Nazi tyranny and terror, with emphasis on the selection of targets: "the official, hierarchical collaborators, agents hired to denounce men of the Resistance and Jews, the Nazi police informants and law enforcement organizations of CSR", thus differentiating it from the Nazi terror. However, partisan memoirs discussed the "elimination of enemies especially heinous", such as torturers, spies and provocateurs. Some orders from branch command partisans insisted on protecting the innocent, instead of providing lists of categories to be hit as individuals deserving of punishment. Part of the Italian press during the war agreed that murders were carried out of most moderate Republican fascists, willing to compromise and negotiate, such as Aldo Resega, Igino Ghisellini, Eugenio Facchini and the philosopher Giovanni Gentile.

Women also participated in the resistance, mainly procuring supplies, clothing and medicines, anti-fascist propaganda, fundraising, maintenance of communications, partisan relays, participated in strikes and demonstrations against fascism. Some women actively participated in the conflict as combatants.

The first detachment of guerilla fighters rose up in Piedmont in mid-1944 as the Garibaldi Brigade Eusebio Giambone. Partisan forces varied by seasons, German and fascist repression and also by Italian topography, never exceeding 200,000 men actively involved, with an important support by residents of occupied territories. Nonetheless it was an important factor that immobilized a conspicuous part of German forces in Italy, and to keep German communication lines insecure.

Fascist forces

When the Italian Resistance movement began following the armistice, with various Italian soldiers of disbanded units and many young people not willing to be conscripted into the fascist forces, Mussolini's Italian Social Republic (RSI) also began putting together an army. This was formed with what was left of the previous Regio Esercito and Regia Marina corps, fascist volunteers and drafted personnel. At first it was organized into four regular divisions (1ª Divisione Bersaglieri Italia - light infantry, 2ª Divisione Granatieri Littorio - grenadiers, 3ª Divisione fanteria di marina San Marco - marines, 4ª Divisione Alpina Monterosa - mountain troops), together with various irregular formations and the fascist militia Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana (GNR) that in 1944 were brought under the control of the regular army.[22]

The fascist republic fought against the partisans to keep control of the territory. The Fascists claimed their armed forces numbered 780,000 men and women. This is disputed and sources indicated that there were no more than 558,000.[23][24] Partisans and their active supporters numbered 82.000 in June 1944.[25]

In addition to regular units of the Republican Army and the Black Brigades, various special units of fascists were organized, at first spontaneously and afterward from regular units that were part of Salò's armed forces. These formations, often including criminals,[26] adopted brutal methods during counterinsurgency operations, repression and retaliation.

Among the first to form was the banda of the Federal Guido Bardi and William Pollastrini in Rome, whose methods shocked even the Germans.[27] In Rome the Banda Koch helped dismantle the clandestine structure of the Partito d'Azione. The so-called Koch Band led by Pietro Koch, then under the protection of General Kurt Maltzer, the Rome region military commander,[28] distinguished themselves with violent methods against anti-fascist partisans. After the fall of Rome, Koch moved to Milan. He gained the confidence of Interior Minister Guido Buffarini Guidi and continued his repressive activity in various Republican police forces.[29] In Tuscany and Veneto operated the Banda Carità, a special unit constituted within the 92nd Legion Blackshirts, which became famous for violent repression, such as the killings of Piazza Tasso" in 1944 in Florence.

In Milan, the Squadra d'azione Ettore Muti (later Autonomous Mobile Legion Ettore Muti) operated under the orders of the former army corporal Francesco Colombo, already expelled from the PNF for embezzlement. Considering him dangerous to the public, in November 1943, the Federal (i.e. fascist provincial leader) Aldo Resega wanted to depose him, but was killed by an attack of GAP. Colombo remained at his post, despite complaints and inquiries.[30] On August 10, 1944 Squadrists of Muti together with the GNR perpetrated the massacre of Piazzale Loreto in Milan. The victims were fifteen anti-fascist rebels, killed in retaliation for an assault against a German truck. Following the massacre, the mayor and chief of the Province of Milan, Piero Parini, resigned in an attempt to strengthen the cohesion of moderate forces, who were undermined by the heavy German repression and various militias of Social Republic.[31]

The chain of command of the National Republican Army was composed of Marshall Graziani and his deputies Mischi and Montagna. They controlled the repression and coordinated anti-partisan actions of the regular troops, the GNR, the Black Brigades and various semi-official police, together with the Germans, who made the reprisals. The Republican Army was an operational tool also thanks to the Graziani call-up for conscription that impressed several thousand Italians. Graziani were only nominally involved in the armed forces under the apolitical CSR, by the armed forces supreme command.[32]

Civil war

Prologue

On July 25, 1943, Mussolini was deposed and arrested and King Victor Emmanuel III imposed Pietro Badoglio as Prime Minister. At first, the new government supported the Axis. Demonstrations celebrating the change were violently repressed. Italy surrendered to the Allies on September 8. Victor left Rome with his Cabinet, leaving the Army without orders. Up to 600,000 Italian soldiers were taken as prisoners by the Nazis and the greatest part of them (about 95%) refused allegiance to the newly established Italian Social Republic (RSI), a fascist state with Benito Mussolini as Head of Government created on September 23. This was made possible by the German occupation of the Italian peninsula via Operation Achse, planned and led by Erwin Rommel. This period featured military and terrorist episodes along with political rivalries among the antifascists. After the armistice with Italy, British forces had two perspectives: that of liberals, who supported democratic parties attempting to overthrow the monarchy, and that of Churchill, who preferred a defeated enemy to a newly recruited ally.[33] The parties were reconstituted after September 8. "Even in this situation over the months the life of the parties was very difficult in the South during years 1943 and 1944 and above all, they (parties) were scarcely able to break through apathy that characterized local populations".[34] The rest of "the great majority of farmers referred to the parish structures".[35] Resources were concentrated to push propaganda among the masses in the Liberated Areas, featuring the common denominator of ending fascist support.[36] IPrefecture reports confirmed the recruitment of former fascists in the ranks of newly constituted parties.[36]

Events

Fascist units disputed for territory with partisan units, often sustained by German forces. Fascists predominated in cities and plain zones, supported by heavy arms, while small partisan units predominant in mountainous areas with better cover, where large formations could not maneuver effectively.

Many violent episodes followed, sometimes pitting fascists against fascists and partisans against partisans. Well known among these is the Porzûs massacre. Communist partisans of the division Natisone (the SAP brigade 13 martiri di Feletto), attached to the Yugoslavian XI Corpus by orders of Togliatti,[37] after reaching the command of one of the many Osoppo Brigades, massacred 20 partisans and a woman, claiming that they were German spies. Among these was commander Francesco De Gregori and brigade commissioner Gastone Valente.[38]

The forces of the Italian Social Republic struggled to keep the insurgency under wraps, resulting in a heavy toll on the German occupation forces stationed to buttress them. Field Marshall Kesselring estimated that from June to August 1944 alone, Italian partisans inflicted a minimum of 20,000 casualties on the Germans (5,000 killed, 7,000 to 8,000 captured/missing, and the same number wounded), while suffering far lower casualties themselves.[39] Kesselring's intelligence officer supplied a higher figure of 30,000 - 35,000 casualties from Partisan activity in those three months (which Kesselring considered too high): 5,000 killed and 25,000-30,000 missing or wounded.[40]

The end

Defeats at the hands of Anglo-American forces left the Germans, and by extension the Italian fascists, increasingly weaker in Italy, until by April their front was collapsing and rear lines were very lightly defended. The Italian partisans took advantage of this with a wide-scale uprising in late April, attacking the retreating Germans and RSI forces. On April 26 Genoa fell, with 14,000 Italian partisans forcing the city's surrender and taking 6,000 German soldiers as prisoners. 25,000 partisans captured Milan the same day, with Turin falling two days later on April 28. Mussolini attempted to withdraw to the mountains on April 27, but was caught by the partisans and killed.[41] Fascist forces surrendered fully on May 2, 1945 after an agreement made with the Allies on April 30, before Germany's surrender to the Allies on May 7, 1945.[42][43][44]

Aftermath

Following the civil war, many soldiers, executives and sympathizers of the fascist Repubblica Sociale were subjected to show trials and executed. Others were killed without a proper trial. Civilians were also killed. Among them were people wrongly accused of collaboration by others who wanted revenge over private grudges. Minister of Interior Mario Scelba estimated the number killed to be 732,[45] but historians dispute this estimate. German historian Hans Woller claimed some 12,060 were killed in 1945 and 6,027 in 1946. Ferruccio Parri said the fascist casualties were as high as 30,000.[46]

Violence decreased after the so-called Togliatti amnesty in 1946.[47]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Despite their name, generally these detachments were not that large, and at their best they counted no more than some hundreds of members. In some cases, there were formations numbering thousands of partisans, until summer 1944 when some joint Italian-German operations would reduce this strength (as in Appendix in De Felice 1997).

References

- ↑ Gianni Oliva, I vinti e i liberati: 8 settembre 1943-25 aprile 1945 : storia di due anni, Mondadori, 1994.

- ↑ Mussolini l'alleato: 1940-1945. Einaudi. 1997. ISBN 978-88-06-11806-8.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Gianni Oliva, I vinti e i liberati: 8 settembre 1943-25 aprile 1945 : storia di due anni, Mondadori, 1994.

- ↑ Bocca 2001, p. 493.

- ↑ "Le Divisioni Ausiliarie". Associazione Nazionale Combattenti Forze Armate Regolari Guerra di Liberazione. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ In 2010, the Ufficio dell'Albo d'Oro recorded 13,021 RSI soldiers killed; however, the Ufficio dell'Albo d'Oro excludes from its lists of the fallen the individuals who committed war crimes. In the context of the RSI, where numerous war crimes were committed in the anti-partisan warfare, and many individuals were therefore involved in such crimes (especially GNR and Black Brigades personnel), this influences negatively the casualty count, under a statistical point of view. The "RSI Historical Foundation" (Fondazione RSI Istituto Storico) has drafted a list that lists the names of some 35,000 RSI military personnel killed in action or executed during and immediately after World War II (including the "revenge killings" that occurred at the end of the hostilities and in their immediate aftermath), including some 13,500 members of the Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana and Milizia Difesa Territoriale, 6,200 members of the Black Brigades, 2,800 Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana personnel, 1,000 Marina Nazionale Repubblicana personnel, 1,900 X MAS personnel, 800 soldiers of the "Monterosa" Division, 470 soldiers of the "Italia" Division, 1,500 soldiers of the "San Marco" Division, 300 soldiers of the "Littorio" Division, 350 soldiers of the "Tagliamento" Alpini Regiment, 730 soldiers of the 3rd and 8th Bersaglieri regiments, 4,000 troops of miscellaneous units of the Esercito Nazionale Repubblicano (excluding the aabove-mentioned Divisions and Alpini and Bersaglieri Regiments), 300 members of the Legione Autonoma Mobile "Ettore Muti", 200 members of the Raggruppamento Anti Partigiani, 550 members of the Italian SS, and 170 members of the Cacciatori degli Appennini Regiment.

- ↑ Ufficio Storico dello Stato Maggiore dell'Esercito. Commissariato generale C.G.V. Ministero della Difesa – Edizioni 1986 (in Italian)

- ↑ Giuseppe Fioravanzo, La Marina dall'8 settembre 1943 alla fine del conflitto, p. 433. In 2010, the Ufficio dell'Albo d'Oro of the Italian Ministry of Defence recorded 15,197 partisans killed; however, the Ufficio dell'Albo d'Oro only considered as partisans the members of the Resistance who were civilians before joining the partisans, whereas partisans who were formerly members of the Italian armed forces (more than half those killed) were considered as members of their armed force of origin.

- ↑ Roma:Instituto Centrale Statistica. Morti E Dispersi Per Cause Belliche Negli Anni 1940–45 Rome, 1957. Total number of violent civilian deaths was 153,147, including 123,119 post armistice. Air raids were responsible for 61,432 deaths, of which 42,613 were post armistice.

- ↑ See as examples the opera of historian Claudio Pavone

- ↑ See as examples the following books (in Italian): Guido Crainz, L'ombra della guerra. Il 1945, l'Italia, Donzelli, 2007 and Hans Woller, I conti con il fascismo. L'epurazione in Italia 1943 - 1948, Il Mulino, 2008.

- ↑ See as examples Renzo De Felice and Gianni Oliva.

- ↑ See as examples the interview to French historian Pierre Milza on the Corriere della Sera of July 14, 2005 (in Italian) and the lessons of historian Thomas Schlemmer at the University of Munchen (in German).

- ↑ Stanley G. Payne, Civil War in Europe, 1905-1949, Cambridge University Press, 2011

- ↑ See as examples the books from Italian historian Giorgio Pisanò and the book L'Italia della guerra civile ("Italy of civil war"), published in 1983 by the Italian writer and journalist Indro Montanelli as the fifteen volume of the Storia d'Italia ("History of Italy") by the same author.

- ↑ Bocca 2001, p. 16.

- ↑ Pietro Secchia, Agire subito from La nostra lotta nr. 3-4, November 1943

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20100403035434/http://www.anpi.it/cln.htm. Archived from the original on April 3, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Oliva 1999, p. 176.

- ↑ Oliva 1999, p. 177.

- ↑ Leo Valiani said about existence of "terrorists of Partito d'Azione". Pavone 1991, p. 495.

- ↑ Decreto Legislativo del Duce nº 469 del 14 agosto 1944 - XXII E.F. "Passaggio della G.N.R. nell'Esercito Nazionale Repubblicano" - Legislative Decree of Duce (Benito Mussolini) n. 469, August 14, 1944

- ↑ Bocca 2001, p. 39.

- ↑ Meldi, Diego (2 February 2015). La repubblica di Salò. Gherardo Casini Editore. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-88-6410-068-5.

- ↑ Bocca 2001, p. 340-341.

- ↑ Ganapini 2010, p. 278.

- ↑ Ganapini 2010, p. 279.

- ↑ Bocca 2001, p. 289.

- ↑ Bocca 2001, pp. 196-199.

- ↑ Ganapini 2010, p. 53.

- ↑ Ganapini 2010, p. 322.

- ↑ F. W. Deakin, History of the Republic of Salò, Torino, Einaudi, 1968, p. 579.

- ↑ M. Ferrari, Recenti tendenze storiografiche sulla seconda guerra mondiale, “Annali di storia contemporanea”, ("Recent trends in historiography on the Second world War", "Annals of contemporary history"), 1995, 1, pp. 411-430, p. 419

- ↑ De Felice 1999, pp. 9-24, 17.

- ↑ Vendramini F., (1987) Il PCI a Belluno e l'avvio della lotta armata. Documenti, “Protagonisti” (The PCI in Belluno and the initiation of armed struggle. Documents, "Protagonists"), 29, pp. 35-42, p. 37

- 1 2 De Felice 1999, p. 21.

- ↑ from La nostra lotta ("Our fight") year II, n.17, October 13, 1944: ...italian formations entering in contact with Yugoslavian formations "will disciplinately stand under Yugoslavian operative command"

- ↑ Oliva, La resa dei conti, pag. 156

- ↑ O'Reilly, Charles (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943-1945. Oxford. Page 243.

- ↑ Kesselring, Albert. "The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Kesselring." Translation and foreword by James Holland and Kenneth Macksey. Skyhorse Publishing; Reprint edition (January 26, 2016). Page 272. Quote: "In the period June–August 1944, my intelligence officer reported to me some 5,000 killed and 25,000-30,000 wounded or kidnapped. These figures seem to me too high. According to my estimate, based on oral reports, a more probable minimum figure for those three months would be 5,000 killed and 7,000-8,000 killed or kidnapped, to which should be added a maximum total of the same number of wounded [as missing]. In any case, the proportion of casualties on the German side alone greatly exceeded the total Partisan losses."

- ↑ O'Reilly, Charles (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943-1945. Oxford. Page 43.

- ↑ "Today In History: Germany Surrenders To The Allies". The Huffington Post. 2013-05-07. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- ↑ "The Surrender of Nazi Germany - History Learning Site". History Learning Site. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- ↑ "Italy, a Nation Divided, 1943 - 1945 | HistoryNet". HistoryNet. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- ↑ See the Atti Parlamentari, Camera dei Deputati, 1952, Discussioni, 11 giugno 1952, p. 38736

- ↑ See the interview with erruccio Parri, on "Corriere della Sera" 15th November 1997. (in Italian)

- ↑ The informal name of the Decree of the President of the Italian Republic, 22 June 1946, no.4

Bibliography

- (in Italian) Bocca, Giorgio (2001). Storia dell'Italia partigiana settembre 1943 - maggio 1945 (in Italian). Mondadori. p. 39.

- Pavone, Claudio (1991). Una guerra civile. Saggio storico sulla moralità della Resistenza (in Italian). Torino: Bollati Boringhieri. ISBN 88-339-0629-9.

- De Felice, Renzo (1997). Mussolini l'alleato II. La guerra civile 1943-1945 (in Italian). Torino: Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-11806-4.

- De Felice, R. (1999). La resistenza ed il regno del sud, "Nuova storia contemporanea" (resistance and the southern kingdom, "New contemporary history"). 2. pp. 9–24 17.

- Stanley G. Payne, Civil War in Europe, 1905-1949, Cambridge University Press, 2011

- Ganapini, Luigi (2010) [1999]. Garzanti, ed. La repubblica delle camicie nere. I combattenti, i politici, gli amministratori, i socializzatori (in Italian) (2a ed.). Milano. ISBN 88-11-69417-5.

- (in German) Virgilio Ilari, Das Ende eines Mythos. Interpretationen und politische Praxis des italienischen Widerstands in der Debatte der frühen neunzinger Jahre, in P. Bettelheim and R. Streibl, Tabu und Geschichte. Zur Kultur des kollektiven Erinners, Picus Verlag, Vienna, 1994, pp. 129–174

- Oliva, Gianni (1999). Mondadori, ed. La resa dei conti. Aprile-maggio 1945: foibe, piazzale Loreto e giustizia partigiana (in Italian). Milano. ISBN 88-04-45696-5.

- Aurelio Lepre (1999). Mondadori, ed. La storia della Repubblica di Mussolini. Salò: il tempo dell'odio e della violenza (in Italian). Milano. ISBN 88-04-45898-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Italian civil war. |