LGBT rights in Italy

| LGBT rights in Italy | |

|---|---|

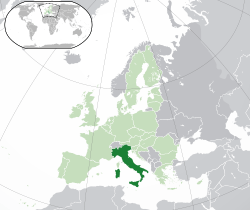

Location of Italy (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Same-sex sexual intercourse legal status | Legal since 1890[1] |

| Gender identity/expression | Transgender persons allowed to change legal gender since 1982 |

| Military service | Gays, lesbians and bisexuals allowed to serve openly |

| Discrimination protections | Sexual orientation protections in employment (see below) |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships |

Unregistered cohabitation and civil unions since 2016,[2] Same-sex marriage banned; first foreign same-sex marriage recognised in 2017 |

| Adoption | Stepchild adoption recognised by courts on a case by case basis |

| Part of a series on |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights |

|---|

|

|

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) rights in Italy have changed significantly over the course of the last years, although LGBT persons may still face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Despite this, Italy is considered a gay-friendly country and public opinion on homosexuality is generally regarded as increasingly culturally liberal, with same-sex unions being legally recognised since June 2016. As of 2018, Italy is the only major country in the Western world with a marriage ban for same-sex couples.

In Italy, both male and female same-sex sexual activity have been legal since 1887, when a new Penal Code was promulgated. A civil unions law passed in May 2016, providing same-sex couples with many of the rights of marriage. Stepchild adoption was, however, excluded from the bill, and it is currently a matter of judicial debate.[3] The same law provides both same-sex and heterosexual couples which live in an unregistered cohabitation with some limited rights.[4][5][6] In 2017, the Italian Supreme Court allowed a marriage between two women to be officially recognised.[5][6]

Transgender people have been allowed to legally change their legal gender since 1982. Although discrimination regarding sexual orientation in employment has been banned since 2003, no other anti-discrimination laws regarding sexual orientation or gender identity and expression have been enacted nationwide; though some Italian regions have enacted more comprehensive anti-discrimination laws. In February 2016, days after the Senate approved the civil union bill, a new poll showed again a large majority in favour of civil unions (69%), a majority for same-sex marriage (56%), but only a minority approving stepchild adoption and LGBT parenting (37%).[7]

LGBT history in Italy

Italian unification in 1860 brought together a number of States which had all (with the exception of two) abolished punishment for private, non-commercial and homosexual acts between consenting adults as a result of the Napoleonic Code.

One of the two exceptions had been the Kingdom of Sardinia which punished homosexual acts between men (although not women) under articles 420–425 of the Penal Code promulgated in 1859 by Victor Emmanuel II.

With the unification, the former Kingdom of Sardinia extended its own criminalizing legislation to the rest of the newly born Kingdom of Italy. However, this legislation did not apply to the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, taking into account the "particular characteristics of those that lived in the south".

This bizarre situation, where homosexuality was illegal in one part of the kingdom, but legal in another, was only reconciled in 1887, with the promulgation of the Zanardelli Code which abolished all differences in treatment between homosexual and heterosexual relations across the entire territory of Italy.

Since the introduction of the first Penal Code in 1889, effective in 1890, there have been no laws against private, adult and consensual homosexual relations.

This situation remained in place despite the fascist promulgation of 19 October 1930 of the Rocco Code. This wanted to avoid discussion of the issue completely, in order to avoid creating public scandal. Repression was a matter for the Catholic Church, and not the Italian State. In any case, it claimed, that most Italians were not interested in an issue only practised by less "healthy" and less "virile" foreigners.

This did not, however, prevent the fascist authorities from targeting male homosexual behaviour with administrative punishment, such as public admonition and confinement; and gays were persecuted in the later years of the regime of Benito Mussolini,[8] and under the Italian Social Republic of 1943–45.

The arrangements of the Rocco Code have remained in place over subsequent decades. Namely the principle that homosexual conduct is an issue of morality and religion, and not criminal sanctions by the State. However, during the post-war period, there have been at least three attempts to re-criminalise it. And such attitudes have made it difficult to bring discussion of measures, for example to recognise homosexual relationships, to the parliamentary sphere.

Issues

Legality of same-sex sexual activity

Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1890.[1] The age of consent is 14 years old, regardless of gender and sexual orientation.

Recognition of same-sex relationships

Since 2016, same-sex couples living in Italy can have shared rights to property, social security or inheritance. Since the 2005 regional elections, many Italian regions governed by centre-left coalitions have passed resolutions in support of French-style PACS (civil unions), including Tuscany, Umbria, Emilia-Romagna, Campania, Marche, Veneto, Apulia, Lazio, Liguria, Abruzzo and Sicily. Lombardy, led by the centre-right House of Freedoms, officially declared their opposition to any recognition of same-sex relationships.[9] All these actions, however, are merely symbolic as regions do not have legislative power on the matter.

Despite the fact that several bills on civil unions or the recognition of rights to unregistered couples had been introduced into the Parliament in the twenty years prior to 2016, none had been approved owing to the strong opposition from the social conservative members of Parliament belonging to both coalitions. On 8 February 2007, the Government led by Romano Prodi introduced a bill,[10] which would have granted rights in areas of labour law, inheritance, taxation and health care to same-sex and opposite-sex unregistered partnerships. The bill was never made a priority of Parliament and was eventually dropped when a new parliament was elected after the Prodi Government lost a confidence vote.

In 2010, the Constitutional Court (Corte Costituzionale) issued a landmark ruling where recognized same sex couples as a "legitimate social formation, similar to and deserving homogeneous treatment as marriage".[11] Since that ruling, the Corte di Cassazione (the last revision court for some issues such as commercial issues or immigration issues) remanded a decision by a Justice of the Peace who had rejected a residence permit to an Algerian citizen, married in Spain to a Spaniard of the same sex. After that, this same judiciary stated that the questura (police office, where residence permits are issued) should deliver a residence permit to a foreigner married with an Italian citizen of his same sex, and cited the ruling.

On 21 July 2015, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that in not recognizing any form of civil union or same-sex marriage in Italy, the country was violating international human rights.[12]

| Wikinews has related news: Italian parliament votes to back same-sex civil unions |

On 2 February 2016, Italian senators started to debate a same-sex civil unions bill.[13] On 25 February 2016, the bill was approved by the Senate in a 173–71 vote. The bill was then sent to the Chamber of Deputies where it passed on 11 May 2016, with 372 voting in favour, compared to 51 against and 99 abstaining.[14] In order to ensure swift passage of the bill, Prime Minister Matteo Renzi had earlier declared it a confidence vote saying it was "unacceptable to have any more delays after years of failed attempts."[15] The civil unions law provides same-sex couples with all the rights of marriage (while not allowing same-sex marriage), however, provisions allowing for stepchild or joint adoption were stricken from an earlier version of the bill.[3] Italian President Sergio Mattarella signed the Civil Union Bill into law on 20 May 2016.[16] It took effect on 5 June 2016.[17]

Adoption and parenting

Adoption and foster care are regulated by the Legge 184/1983. Adoption is in principle permitted only to married couples who must be only opposite-sex couples. Indeed, according to Italian law, there are no restrictions on foster care. In a limited number of situations, the law provides for "adoption in particular cases" by a single person, however, and this has been interpreted by some courts, including on appeal court level, to include the possibility of stepchild adoption for unmarried (opposite-sex and same-sex) couples.[18]

On 11 January 2013, the Court of Cassation upheld a lower decision of court which granted the sole custody of a child to a lesbian mother. The father of the child complained about the homosexual relationship of the mother. The Supreme Court rejected the father's appeal because it was not argued properly.[19]

On 15 November 2013, it was reported that the Court of Bologna chose a same-sex couple to foster a 3-year-old child.[20]

On 1 March 2016, a Rome family court approved a lesbian couple's request to simultaneously adopt each other's daughters.[21] Since 2014, the Rome Family Court has made at least 15 rulings upholding requests for gay people to be allowed to adopt their partners' children.[21] On 29 April 2016, Marilena Grassadonia, president of the Rainbow Families Association, won the right to adopt her wife's twin boys.[22] The possibility of stepchild adoption was confirmed by the Court of Cassation in a decision published on 22 June 2016.[23]

In February 2017, a Trento court recognized both male same-sex partners as dads of two surrogate-born kids, born in the United States.[24]

In March 2017, the Florence Court for Minors recognised a foreign adoption by a same-sex couple.[25][26] The Milan Court of Appeal also recognised a foreign same-sex adoption in June 2017.[27]

In April 2018, a lesbian couple in Turin was permitted by city officials to register their son, born through IVF, as the child of both parents.[28] Two other same-sex couples also had their children officially registered. A few days later, a same-sex couple in Rome was similarly allowed to register their daughter.[29]

Discrimination protections

In 2002, Franco Grillini introduced legislation that would modify article III of the Italian Constitution to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.[30][31] It was not successful.

Since 2003, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in employment is illegal throughout the whole country, in conformity with EU directives.

In 2006, Grillini again introduced a proposal to expand anti-discrimination laws, this time adding gender identity as well as sexual orientation.[31] It received less support than the previous one had.

In 2008, Danilo Giuffrida was awarded 100,000 euros compensation after having been ordered to re-take his driving test by the Italian Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport due to his sexuality; the judge said that the Ministry of Transport was in clear breach of anti-discrimination laws.[32]

In 2009, the Italian Chamber of Deputies shelved a proposal against homophobic hate crimes, that would have allowed increased sentences for violence against gay and bisexual individuals, approving the preliminary questions moved by Union of the Centre and supported by Lega Nord and The People of Freedom[33] (although 9 deputies, politically near to the President of the Chamber Gianfranco Fini, have voted against).[34] Deputy Paola Binetti, who belongs to Democratic Party, also voted against party guidelines.[35]

On 16 May 2013, a bill which will prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity was presented in a press conference by four deputies of four different parties.[36] The bill is cosponsored by 221 MPs of the Chamber of Deputies but none of the center-right side has pledged his support yet. In addition to this bill some deputies introduced another two bills. On 7 July, the Justice Committee advanced a unified bill.[37]

The bill was amended in compliance of the request of some conservative MPs who fear to be fined or jailed for stating their opposition to the recognition of same-sex unions. On 5 August, the House started to consider the bill. On 19 September 2013, the House of Deputies passed the bill in a 228–58 vote (and 108 abstentions). On the same day, a controversial amendment passed, which will protect free speech for politicians and clergymen.[38] On 29 April 2014, the Senate began examining the bill.[39] As of May 2017, the bill is still in the Senate Judicial Commission, being blocked by several hundred amendments from conservative MPs.[40]

Regional laws

In 2004, Tuscany became the first Italian region to ban discrimination against homosexuals[41] in the areas of employment, education, public services and accommodations. The Berlusconi Government challenged the new law in court, asserting that only the central Government had the right to pass such a law. The Constitutional Court overturned the provisions regarding accommodations (with respect to private homes and religious institutions), but otherwise upheld most of the legislation.[42] Since then, the region of Piedmont has also enacted a similar measure.[43] Sicily and Umbria followed suit in March 2015 and April 2017, respectively.[44][45][46][47][48]

Gender identity and expression

Cross dressing is legal in Italy, and sex reassignment surgeries are also legal, with medical approval. However, gender identity is not a part of official anti-discrimination law.

In 1982, Italy became the third nation in the world to recognise the right to change one's legal gender. Before Italy, only Sweden (1972) and Germany (then-West Germany) (1980) recognised this right.

In 2006, a police officer was reportedly fired for cross-dressing in public while off duty.[49]

The first transgender MP was Vladimir Luxuria, who was elected in 2006 as a representative of the Communist Refoundation Party. While she was not reelected, she went on to be the winner of a popular reality television show called L'Isola dei Famosi.[50]

In 2005, a couple got legally married as husband and wife. Some years later, one of the parties transitioned as a trans woman. In 2009, she was legally recognized as such according to the Italian law on transsexualism (Legge 14 aprile 1982, n. 164). Later the couple discovered that their marriage was dissolved because the couple became a same-sex couple, even though they did not ask a civil court to divorce.

The Law on Transsexualism (164/1982) prescribes that when a transsexual person is married to another person the couple should divorce, but in the case of the trans woman mentioned above (Alessandra) and her wife, there was no will to divorce. The couple asked the Civil Court of Modena to nullify the order of dissolvement of their marriage. On 27 October 2010, the court ruled in favour of the couple. The Italian Ministry of Interior appealed the decision and the Court of Appeal of Bologna reversed the trial decision.

Later the couple, appealed the decision to the Court of Cassation. On 6 June 2013, the Cassation asked the Constitutional Court whether the Law on Transsexualism was unconstitutional when it ordered the dissolvement of marriage by applying the Divorce Law (Legge 1 dicembre 1970, n. 898) even if the couple did not ask to do so. In 2014, the Constitutional Court finally ruled the case in favour of the couple, allowing them to stay married.[51]

On 21 May 2015, the Court of Cassation also decided that sterilisation is not required in order to obtain a legal gender change.[52]

Military service

Lesbians, gays and bisexuals are not banned from military service. The Armed Forces of Italy cannot deny men or women the right to serve within their ranks because of their sexual orientation, as this would be a violation of constitutional rights.

Blood donation

Gay and bisexual men have been allowed to donate blood since 2001.[53]

LGBT rights groups and public campaigns

The major national organization for LGBT rights in Italy is called Arcigay. It was founded in 1985, and has advocated for the recognition of same-sex couples and LGBT rights generally.

Some openly LGBT politicians include:

- Vladimir Luxuria, first openly transgender member of Parliament in Europe, and the world's second openly transgender MP after New Zealander Georgina Beyer; former deputy for the Communist Refoundation Party

- Nichi Vendola, leader of Left Ecology Freedom and former President of Apulia

- Rosario Crocetta, former President of Sicily and a prominent figure in the Democratic Party

- Paola Concia, former member of the Chamber of Deputies for the Democratic Party

- Daniele Capezzone, spokesperson for the People of Freedom party

- Franco Grillini, former member of the Chamber of Deputies for the Democrats of the Left

- Marco Pannella, former member of the European Parliament and leader of the Italian Radical Party (came out after retirement)

- Alfonso Pecoraro Scanio, former Minister of Environment and first openly bisexual minister

In 2007, an advert showing a baby wearing a wristband label that said "homosexual" caused controversy. The advert was part of a regional government campaign to combat anti-gay discrimination.[54]

Social conditions

Public opinion

According to data from the 2010 Italy Eurispes report released 29 January, the percentage of Italians who have a positive attitude towards homosexuality and are in favor of legal recognition of gay and lesbian couples is growing.

According to a 2010 poll, 82% of Italians considered homosexuals equal to all others. 41% thought that same-sex couples should have the right to marry in a civil ceremony, and 20.4% agreed with civil unions. In total, 61.4% were in favor of a form of legal recognition for gay and lesbian couples. This was an increase of 2.5% from the previous year (58.9%) and almost 10% in 7 years (51.6% in 2003). "This is further proof that Italians are ahead of their national institutions. Our Parliament hears more and more people on the issue and what it hears is to soon approve a law that guarantees gay people the opportunity to publicly recognize their families, as is done in 20 European countries "- said the national president of Arcigay, Aurelio Mancuso.[55]

| Italians support for gay rights | 2009 | 2010 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| recognition for same-sex couples | 58.9% | 61.4% | 62.8% | 79% | – | – | 69%[56] | – |

| same-sex marriage | 40.4% | 41% | 43.9% | 48% | 55% | 53%[57] | 56%[58] | 59% |

A 2013 Pew Research Center opinion survey of various countries throughout the world showed that 74% of the Italian population believed that homosexuality should be accepted by society (the 8th highest of all the countries polled), while 18% believed it should not.[59] Young people were generally more accepting: 86% of people between 18 and 29 were accepting of gay people, while 80% of people between 30 and 49 and 67% of people over 50 held the same belief. In a 2007 version of this survey, 65% of Italians were accepting of gay people, meaning that there was a net gain of 9% from 2007 to 2013 (the 4th highest gain in acceptance of gay people of the countries surveyed).

In December 2016, a survey was conducted by the Williams Institute in collaboration with IPSOS, in 23 countries (including Italy) on their attitudes towards transgender people.[60][61] The study showed a relatively liberal attitude from Italians towards transgender people. According to the study, 78% of Italians supported allowing transgender people to change their gender on their legal documents (the 4th highest percentage of the countries surveyed), with 29% supporting the idea of allowing them to do so without any surgery or doctor's/government approval (the 6th highest percentage of the countries surveyed). In addition to that, 78.5% of Italians believed that transgender people should be protected by the Government from discrimination, 57.7% believed that transgender people should be allowed to use the restroom corresponding to their gender identity rather than their birth sex, and only 14.9% believed that transgender people have a mental illness (the 6th lowest of the countries surveyed).

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent (14) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws concerning gender identity | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples (e.g. cohabitation or civil union) | |

| Single LGBT individual allowed to adopt | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Gays, lesbians and bisexuals allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Conversion therapy banned on minors | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians and automatic parenthood | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood | |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGBT in Italy. |

- Human rights in Italy

- LGBT rights in Europe

- LGBT rights in the European Union

References

- 1 2 State-sponsored Homophobia: A world survey of laws prohibiting same sex activity between consenting adults Archived 19 July 2013 at WebCite

- ↑ (in Italian) Unioni civili e convivenze di fatto

- 1 2 "Italian senate passes watered-down bill recognising same-sex civil unions". The Guardian. 25 February 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ (in Italian) Unioni civili, matrimoni e convivenze. Ecco cosa cambia in un grafico

- 1 2 3 (in Italian) Monica Cirinnà: con le unioni civili è appena iniziato il cammino verso l’uguaglianza

- 1 2 3 (in Italian) Nozze gay in Italia: Cassazione convalida il primo matrimonio tra due donne

- ↑ "Atlante Politico 54 - febbraio 2016 - Atlante politico - Demos & Pi".

- ↑ (in Italian) L'omosessualità in Italia Archived 4 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ (in Italian) Diritti gay: per la Regione Lombardia esistono solo le famiglie naturali

- ↑ "Italy may recognise unwed couples". BBC News. 9 February 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ↑ Sentenza N. 138 ; Repubblica Italiana in Nome Del Popolo Italiano La Corte Costituzionale

- ↑ Advocate: European Court Rules Italy's Same-Sex Marriage and Civil Union Ban a Human Rights Violation

- ↑ "Italian senators debate same-sex union bill under Vatican's watchful eye". Religion News Service. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ↑ "Senate to examine civil unions bill on Wednesday (2)". Gazzetta del Sud Online. 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "Italy says 'yes' to gay civil unions". The Local. 11 May 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ "Mattarella signs civil-unions law". ANSA. 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "Unioni civili, in Gazzetta la legge: in vigore dal 5 giugno". Il Sole 24. 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Adozioni gay, la Corte d'Appello di Roma conferma: sì a due mamme". Corriere della Sera. 23 December 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ "Famiglie gay, Cassazione: "Un bambino può crescere bene"". il Fatto Quotidiano. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ "Bologna segue la Cassazione: bimba di tre anni in affido a una coppia gay". Corriere di Bologna. 15 November 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- 1 2 "Italian court approves lesbian couple's adoption of each other's children". The Guardian. 2 March 2016.

- ↑ "Italian couple win same-sex adoption case". The Guardian. 29 April 2016.

- 1 2 (in Italian)"Cassazione, via libera alla stepchild adoption in casi particolari". Repubblica.

- 1 2 Court recognises gays as dads of 2 surrogate-born kids

- 1 2 Adoption of kids by gays recognised

- 1 2 Italy just recognized two gay men as adoptive fathers for the first time

- 1 2 (in Italian) Due padri: Corte d’Appello di Milano ordina la trascrizione di un’adozione gay in Usa

- ↑ "Italy Takes A Grande Step Forward For LGBT Parental Rights". Above the Law. 2 May 2018.

- ↑ (in Italian) Quei sindaci che sfidano la legge per registrare figli di coppie gay

- ↑ Pedote, Paolo; Nicoletta Poidimani (2007). We will survive!: lesbiche, gay e trans in Italia. Mimesis Edizioni. p. 181.

- 1 2 Borrillo, Daniel (2009). Omofobia. Storia e critica di un pregiudizio. Edizioni Dedalo. p. 155.

- ↑ "Italian wins gay driving ban case". BBC News. 13 July 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ↑ "Camera affossa testo di legge su omofobia" (in Italian). Reuters. 13 October 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ↑ "Omofobia, testo bocciato alla Camera E nel Pd esplode il caso Binetti". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 13 October 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ↑ "Omofobia, la Camera affossa il testo Caos nel Pd: riesplode il caso Binetti". La Stampa (in Italian). 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ↑ "Omofobia, un terzo dei parlamentari firma la nuova proposta di legge". Il Messaggero (in Italian). 16 May 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ Omofobia, testo Pd-Pdl passa in commissione Giustizia. Lavori socialmente utili a chi discrimina gli omosessuali

- ↑ "Omofobia, sì alle aggravanti. Ma è scontro nella maggioranza". la Repubblica (in Italian). 19 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ (in Italian) Senate Act no. 404

- ↑ (in Italian) Quella legge sull’omofobia bloccata al Senato da anni

- ↑ Text of Legislation (in Italian) Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Text of Decision (in Italian) Archived 19 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Text of Legislation (in Italian) Archived 19 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ (in Italian) Approvata legge regionale anti-omofobia

- ↑ (in Italian) Approvata legge contro l’omofobia, risultato storico per la Sicilia

- ↑ (in Italian) Approvata legge contro l’omotransfobia, dall’Umbria riparte la lotta alle discriminazioni [VIDEO]

- ↑ (in Italian) Dopo 10 anni una legge contro tutte le discriminazioni

- ↑ (in Italian) Arcigay Palermo: “legge contro l’omofobia è un risultato storico”.

- ↑ "Cross-dressing Italian cop given the boot". UPI. 29 December 2006.

- ↑ "Luxuria: "Ora la sinistra mi critica ma vado avanti"". il Giornale (in Italian). 25 November 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ↑ Nadeau, Barbie Latza (16 June 2014). "Italian Transgender Ruling Gives Green Light to Civil Unions". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ Court of Cassation judgment of 21 May 2015

- 1 2 "Gay: vietato donare sangue, ma solo con prove rischi – Altre news – ANSA Europa". ANSA. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ↑ "Gay newborn poster sparks row in Italy". Reuters. 25 October 2007.

- ↑ "La regolamentazione delle coppie di fatto". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 15 May 2009.

- ↑ (in Italian) ATLANTE POLITICO 54 - FEBBRAIO 2016

- ↑ Atlante Politico - Gli Italiani E Il Matrimonio Gay

- ↑ POLITICO 54 - FEBBRAIO 2016

- ↑ "The Global Divide on Homosexuality". Pew Research Center. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ↑ Flores, Andrew; Brown, Taylor; Park, Andrew (December 2016), Public Support for Transgender Rights: A Twenty-three Country Survey (PDF), retrieved 21 August 2017

- ↑ "This Is How 23 Countries Feel About Transgender People". Buzzfeed. 29 December 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ (in Italian) Legge antidiscriminazioni della Toscana ridimensionata

- ↑ (in Italian) REGIONE TOSCANA. LEGGE REGIONALE 15 NOVEMBRE 2004, N. 63

- ↑ Italian Court recognizes gay marriage officiated abroad for the first time

- ↑ "Italy says operation not needed for sex change". Retrieved 21 August 2017.