Sappho

Sappho (/ˈsæfoʊ/; Aeolic Greek Ψαπφώ Psapphô; c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an archaic Greek poet from the island of Lesbos.[lower-alpha 1] Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by a lyre.[2] Most of Sappho's poetry is now lost, and what is extant has survived only in fragmentary form, except for one complete poem: the "Ode to Aphrodite". As well as lyric poetry, ancient commentators claimed that Sappho wrote elegiac and iambic poetry. Three epigrams attributed to Sappho are extant, but these are actually Hellenistic imitations of Sappho's style.

Little is known of Sappho's life. She was from a wealthy family from Lesbos, though the names of both of her parents are uncertain. Ancient sources say that she had three brothers; the names of two of them are mentioned in the Brothers Poem discovered in 2014. She was exiled to Sicily around 600 BC, and may have continued to work until around 570. Later legends surrounding Sappho's love for the ferryman Phaon and her death are unreliable.

Sappho was a prolific poet, probably composing around 10,000 lines. Her poetry was well-known and greatly admired through much of antiquity, and she was among the canon of nine lyric poets most highly esteemed by scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria. Sappho's poetry is still considered extraordinary and her works continue to influence other writers. Beyond her poetry, she is well known as a symbol of love and desire between women.[3]

Ancient sources

There are three sources of information about Sappho's life: her testimonia, the history of her times, and what can be gleaned from her own poetry — although scholars are cautious when reading poetry as a biographical source.[5] Testimonia is a term of art in ancient studies that refers to collections of classical biographical and literary references to classical authors. The testimonia regarding Sappho do not contain references contemporary to Sappho.[lower-alpha 2][6] The representations of Sappho's life that occur in the testmonia, always need to be assessed for accuracy, many of them are certainly not correct.[7][8] The testimonia are also a source of knowledge regarding how Sappho's poetry was received in antiquity.[9] Some details mentioned in the testimonia are derived from Sappho's own poetry, which is of great interest, especially considering the testimonia originate from a time when more of Sappho's poetry was extant than is the case for modern readers.[10][11]

Life

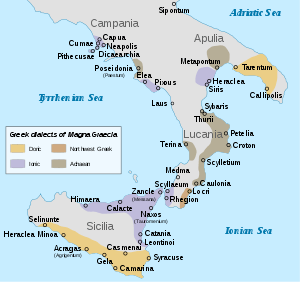

Little is known about Sappho's life for certain.[12] She was from Mytilene on the island of Lesbos[13][lower-alpha 3] and was probably born around 630 BC.[16][lower-alpha 4] Tradition names her mother as Cleïs,[18] though ancient scholars may simply have guessed this name, assuming that Sappho's daughter Cleïs was named after her.[14] Sappho's father's name is less certain. Ten names are known for Sappho's father from the ancient testimonia;[lower-alpha 5] this proliferation of possible names suggests that he was not explicitly named in any of Sappho's poetry.[20] The earliest and most commonly attested name for Sappho's father is Scamandronymus.[lower-alpha 6] In Ovid's Heroides, Sappho's father died when she was seven.[21] Sappho's father is not mentioned in any of her surviving works, but Campbell suggests that this detail may have been based on a now-lost poem.[22] Sappho's own name is found in numerous variant spellings, even in her own Aeolian dialect; the form that appears in her own extant poetry is Psappho.[23][24]

No reliable portrait of Sappho's physical appearance has survived; all extant representations, ancient and modern, are artists' conceptions.[25] In the Tithonus poem she describes her hair as now white but formerly melaina, i.e. black. A literary papyrus of the second century A.D. describes her as pantelos mikra, quite tiny.[26] Alcaeus possibly describes Sappho as "violet-haired",[27] which was a common Greek poetic way of describing dark hair.[28][29][30] Some scholars dismiss this tradition as unreliable.[31]

Sappho was said to have three brothers: Erigyius, Larichus, and Charaxus. According to Athenaeus, Sappho often praised Larichus for pouring wine in the town hall of Mytilene, an office held by boys of the best families.[33] This indication that Sappho was born into an aristocratic family is consistent with the sometimes rarefied environments that her verses record. One ancient tradition tells of a relation between Charaxus and the Egyptian courtesan Rhodopis. Herodotus, the oldest source of the story, reports that Charaxus ransomed Rhodopis for a large sum and that Sappho wrote a poem rebuking him for this.[lower-alpha 7][35]

Sappho may have had a daughter named Cleïs, who is referred to in two fragments.[36] Not all scholars accept that Cleïs was Sappho's daughter. Fragment 132 describes Cleïs as "παῖς" (pais), which, as well as meaning "child", can also refer to the "youthful beloved in a male homosexual liaison".[37] It has been suggested that Cleïs was one of Sappho's younger lovers, rather than her daughter,[37] though Judith Hallett argues that the language used in fragment 132 suggests that Sappho was referring to Cleïs as her daughter.[38]

According to the Suda, Sappho was married to Kerkylas of Andros.[14] However, the name appears to have been invented by a comic poet: the name "Kerkylas" comes from the word "κέρκος" (kerkos), a possible meaning of which is "penis", and is not otherwise attested as a name,[39] while "Andros", as well as being the name of a Greek island, is a form of the Greek word "ἀνήρ" (aner), which means man.[18] Thus, the name may be a joke name, and as such could be rendered as "Dick Allcock from the Isle of Man".[39]

Sappho and her family were exiled from Lesbos to Syracuse, Sicily around 600 BC.[13] The Parian Chronicle records Sappho going into exile some time between 604 and 591.[40] This may have been as a result of her family's involvement with the conflicts between political elites on Lesbos in this period,[41] the same reason for Sappho's contemporary Alcaeus' exile from Mytilene around the same time.[42] Later the exiles were allowed to return.

A tradition going back at least to Menander (Fr. 258 K) suggested that Sappho killed herself by jumping off the Leucadian cliffs for love of Phaon, a ferryman. This is regarded as unhistorical by modern scholars, perhaps invented by the comic poets or originating from a misreading of a first-person reference in a non-biographical poem.[32] The legend may have resulted in part from a desire to assert Sappho as heterosexual.[43]

Sexuality

Today Sappho, for many, is a symbol of female homosexuality;[18] the common term lesbian is an allusion to Sappho, originating from the name of the island of Lesbos, where she was born.[lower-alpha 8][44] However, she has not always been so considered. In classical Athenian comedy (from the Old Comedy of the fifth century to Menander in the late fourth and early third centuries BC), Sappho was caricatured as a promiscuous heterosexual woman,[45] and it is not until the Hellenistic period that the first testimonia which explicitly discuss Sappho's homoeroticism are preserved. The earliest of these is a fragmentary biography written on papyrus in the late third or early second century BC,[46] which states that Sappho was "accused by some of being irregular in her ways and a woman-lover".[28] Denys Page comments that the phrase "by some" implies that even the full corpus of Sappho's poetry did not provide conclusive evidence of whether she described herself as having sex with women.[47] These ancient authors do not appear to have believed that Sappho did, in fact, have sexual relationships with other women, and as late as the tenth century the Suda records that Sappho was "slanderously accused" of having sexual relationships with her "female pupils".[48]

Among modern scholars, Sappho's sexuality is still debated – André Lardinois has described it as the "Great Sappho Question".[49] Early translators of Sappho sometimes heterosexualised her poetry.[50] Ambrose Philips' 1711 translation of the Ode to Aphrodite portrayed the object of Sappho's desire as male, a reading that was followed by virtually every other translator of the poem until the twentieth century,[51] while in 1781 Alessandro Verri interpreted fragment 31 as being about Sappho's love for Phaon.[52] Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker argued that Sappho's feelings for other women were "entirely idealistic and non-sensual",[53] while Karl Otfried Müller wrote that fragment 31 described "nothing but a friendly affection":[54] Glenn Most comments that "one wonders what language Sappho would have used to describe her feelings if they had been ones of sexual excitement" if this theory were correct.[54] By 1970, it would be argued that the same poem contained "proof positive of [Sappho's] lesbianism".[55]

Today, it is generally accepted that Sappho's poetry portrays homoerotic feelings:[56] as Sandra Boehringer puts it, her works "clearly celebrate eros between women".[57] Toward the end of the twentieth century, though, some scholars began to reject the question of whether or not Sappho was a lesbian – Glenn Most wrote that Sappho herself "would have had no idea what people mean when they call her nowadays a homosexual",[54] André Lardinois stated that it is "nonsensical" to ask whether Sappho was a lesbian,[58] and Page duBois calls the question a "particularly obfuscating debate".[59]

One of the major focuses of scholars studying Sappho has been to attempt to determine the cultural context in which Sappho's poems were composed and performed.[60] Various cultural contexts and social roles played by Sappho have been suggested, including teacher, cult-leader, and poet performing for a circle of female friends.[60] However, the performance contexts of many of Sappho's fragments are not easy to determine, and for many more than one possible context is conceivable.[61]

One longstanding suggestion of a social role for Sappho is that of "Sappho as schoolmistress".[62] At the beginning of the twentieth century, the German classicist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff posited that Sappho was a sort of schoolteacher, in order to "explain away Sappho's passion for her 'girls'" and defend her from accusations of homosexuality.[63] The view continues to be influential, both among scholars and the general public,[64] though more recently the idea has been criticised by historians as anachronistic[65] and has been rejected by several prominent classicists as unjustified by the evidence. In 1959, Denys Page, for example, stated that Sappho's extant fragments portray "the loves and jealousies, the pleasures and pains, of Sappho and her companions"; and he adds, "We have found, and shall find, no trace of any formal or official or professional relationship between them, ... no trace of Sappho the principal of an academy."[66] David A. Campbell in 1967 judged that Sappho may have "presided over a literary coterie", but that "evidence for a formal appointment as priestess or teacher is hard to find".[67] None of Sappho's own poetry mentions her teaching, and the earliest testimonium to support the idea of Sappho as a teacher comes from Ovid, six centuries after Sappho's lifetime.[68] Despite these problems, many newer interpretations of Sappho's social role are still based on this idea.[69] In these interpretations, Sappho was involved in the ritual education of girls,[69] for instance as a trainer of choruses of girls.[60]

Even if Sappho did compose songs for training choruses of young girls, not all of her poems can be interpreted in this light,[70] and despite scholars' best attempts to find one, Yatromanolakis argues that there is no single performance context to which all of Sappho's poems can be attributed. Parker argues that Sappho should be considered as part of a group of female friends for whom she would have performed, just as her contemporary Alcaeus is.[71] Some of her poetry appears to have been composed for identifiable formal occasions,[72] but many of her songs are about – and possibly were to be performed at – banquets.[73]

Works

Sappho probably wrote around 10,000 lines of poetry; today, only about 650 survive.[74] She is best known for her lyric poetry, written to be accompanied by music.[74] The Suda also attributes to Sappho epigrams, elegiacs, and iambics; three of these epigrams are extant, but are in fact later Hellenistic poems inspired by Sappho, as are the iambic and elegiac poems attributed to her in the Suda.[75] Ancient authors claim that Sappho primarily wrote love poetry,[76] and the indirect transmission of Sappho's work supports this notion.[77] However, the papyrus tradition suggests that this may not have been the case: a series of papyri published in 2014 contains fragments of ten consecutive poems from Book I of the Alexandrian edition of Sappho, of which only two are certainly love poems, while at least three and possibly four are primarily concerned with family.[77]

Ancient editions

Sappho's poetry was probably first written down on Lesbos, either in her lifetime or shortly afterwards,[78] initially probably in the form of a score for performers of Sappho's work.[79] In the fifth century, Athenian book publishers probably began to produce copies of Lesbian lyric poetry, some including explanatory material and glosses as well as the poems themselves.[78] Some time in the second or third century, Alexandrian scholars produced a critical edition of Sappho's poetry.[80] There may have been more than one Alexandrian edition – John J. Winkler argues for two, one edited by Aristophanes of Byzantium and another by his pupil Aristarchus of Samothrace.[79] This is not certain – ancient sources tell us that Aristarchus' edition of Alcaeus replaced the edition by Aristophanes, but are silent on whether Sappho's work, too, went through multiple editions.[81]

The Alexandrian edition of Sappho's poetry was based on the existing Athenian collections,[78] and was divided into at least eight books, though the exact number is uncertain.[82] Many modern scholars have followed Denys Page, who conjectured a ninth book in the standard edition;[82] Yatromanolakis doubts this, noting that though testimonia refer to an eighth book of Sappho's poetry, none mention a ninth.[83] Whatever its make-up, the Alexandrian edition of Sappho probably grouped her poems by their metre: ancient sources tell us that each of the first three books contained poems in a single specific metre.[84] Ancient editions of Sappho, possibly starting with the Alexandrian edition, seem to have ordered the poems in at least the first book of Sappho's poetry – which contained works composed in Sapphic stanzas – alphabetically.[85]

Even after the publication of the standard Alexandrian edition, Sappho's poetry continued to circulate in other poetry collections. For instance, the Cologne Papyrus on which the Tithonus poem is preserved was part of a Hellenistic anthology of poetry, which contained poetry arranged by theme, rather than by metre and incipit, as it was in the Alexandrian edition.[86]

Surviving poetry

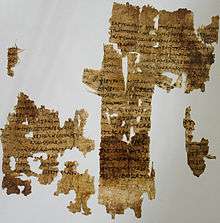

The earliest surviving manuscripts of Sappho, including the potsherd on which fragment 2 is preserved, date to the third century BC, and thus predate the Alexandrian edition.[79] The latest surviving copies of Sappho’s poems transmitted directly from ancient times are written on parchment codex pages from the sixth and seventh centuries AD, and were surely reproduced from ancient papyri now lost.[87] Manuscript copies of Sappho's works may have survived a few centuries longer, but around the 9th century her poetry appears to have disappeared,[88] and by the twelfth century, John Tzetzes could write that "the passage of time has destroyed Sappho and her works".[89]

According to legend, Sappho's poetry was lost because the church disapproved of her morals.[18] These legends appear to have originated in the renaissance – around 1550, Jerome Cardan wrote that Gregory Nazianzen had Sappho's work publicly destroyed, and at the end of the sixteenth century Joseph Justus Scaliger claimed that Sappho's works were burned in Rome and Constantinople in 1073 on the orders of Pope Gregory VII.[88] In reality, Sappho's work was probably lost as the demand for it was insufficiently great for it to be copied onto parchment when codices superseded papyrus scrolls as the predominant form of book.[90] Another contributing factor to the loss of Sappho's poems may have been the perceived obscurity of her Aeolic dialect,[91][92][90][93] which contains many archaisms and innovations absent from other ancient Greek dialects.[94] During the Roman period, by which time the Attic dialect had become the standard for literary compositions,[95] many readers found Sappho's dialect difficult to understand[92] and, in the second century AD, the Roman author Apuleius specifically remarks on its "strangeness".[95]

Only approximately 650 lines of Sappho's poetry still survive, of which just one poem – the "Ode to Aphrodite" – is complete, and more than half of the original lines survive in around ten more fragments. Many of the surviving fragments of Sappho contain only a single word[74] – for example, fragment 169A is simply a word meaning "wedding gifts",[96] and survives as part of a dictionary of rare words.[97] The two major sources of surviving fragments of Sappho are quotations in other ancient works, from a whole poem to as little as a single word, and fragments of papyrus, many of which were discovered at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt.[98] Other fragments survive on other materials, including parchment and potsherds.[75] The oldest surviving fragment of Sappho currently known is the Cologne papyrus which contains the Tithonus poem,[99] dating to the third century BC.[100]

Until the last quarter of the nineteenth century, only the ancient quotations of Sappho survived. In 1879, the first new discovery of a fragment of Sappho was made at Fayum.[101] By the end of the nineteenth century, Grenfell and Hunt had begun to excavate an ancient rubbish dump at Oxyrhynchus, leading to the discoveries of many previously unknown fragments of Sappho.[18] Fragments of Sappho continue to be rediscovered. Most recently, major discoveries in 2004 (the "Tithonus poem" and a new, previously unknown fragment)[102] and 2014 (fragments of nine poems: five already known but with new readings, four, including the "Brothers Poem", not previously known)[103] have been reported in the media around the world.[18]

Style

Sappho clearly worked within a well-developed tradition of Lesbian poetry, which had evolved its own poetic diction, meters, and conventions. Among her famous poetic forebears were Arion and Terpander.[104] Nonetheless, her work is innovative; it is some of the earliest Greek poetry to adopt the "lyric 'I'" – to write poetry adopting the viewpoint of a specific person, in contrast to the earlier epic poets Homer and Hesiod, who present themselves more as "conduits of divine inspiration".[105] Her poetry explores individual identity and personal emotions – desire, jealousy, and love; it also adopts and reinterprets the existing imagery epic poetry in exploring these themes.[106]

Sappho's poetry is known for its clear language and simple thoughts, sharply-drawn images, and use of direct quotation which brings a sense of immediacy.[107] Unexpected word-play is a characteristic feature of her style.[108] An example is from fragment 96: "now she stands out among Lydian women as after sunset the rose-fingered moon exceeds all stars",[109] a variation of the Homeric epithet "rosy-fingered Dawn".[110] Sappho's poetry often uses hyperbole, according to ancient critics "because of its charm".[111] An example is found in fragment 111, where Sappho writes that "The groom approaches like Ares[...] Much bigger than a big man".[112]

Leslie Kurke groups Sappho with those archaic Greek poets from what has been called the "élite" ideological tradition,[lower-alpha 9] which valued luxury (habrosyne) and high birth. These elite poets tended to identify themselves with the worlds of Greek myths, gods, and heroes, as well as the wealthy East, especially Lydia.[114] Thus in fragment 2 Sappho describes Aphrodite "pour into golden cups nectar lavishly mingled with joys",[115] while in the Tithonus poem she explicitly states that "I love the finer things [habrosyne]".[116][117][lower-alpha 10] According to Page DuBois, the language, as well as the content, of Sappho's poetry evokes an aristocratic sphere.[119] She contrasts Sappho's "flowery,[...] adorned" style with the "austere, decorous, restrained" style embodied in the works of later classical authors such as Sophocles, Demosthenes, and Pindar.[119]

Traditional modern literary critics of Sappho's poetry have tended to see her poetry as a vivid and skilled but spontaneous and naive expression of emotion: typical of this view are the remarks of H. J. Rose that "Sappho wrote as she spoke, owing practically nothing to any literary influence," and that her verse displays "the charm of absolute naturalness."[120] Against this essentially romantic view, one school of more recent critics argues that, on the contrary, Sappho's poetry displays and depends for its effect on a sophisticated deployment of the strategies of traditional Greek rhetorical genres.[121]

Legacy

Ancient reputation

In antiquity Sappho's poetry was highly admired, and several ancient sources refer to her as the "tenth Muse".[122] The earliest surviving poem to do so is a third-century BC epigram by Dioscorides,[123][124] but poems are preserved in the Greek Anthology by Antipater of Sidon[125][126] and attributed to Plato[127][128] on the same theme. She was sometimes referred to as "The Poetess", just as Homer was "The Poet".[129] The scholars of Alexandria included Sappho in the canon of nine lyric poets.[130] According to Aelian, the Athenian lawmaker and poet Solon asked to be taught a song by Sappho "so that I may learn it and then die".[131] This story may well be apocryphal, especially as Ammianus Marcellinus tells a similar story about Socrates and a song of Stesichorus, but it is indicative of how highly Sappho's poetry was considered in the ancient world.[132]

Sappho's poetry also influenced other ancient authors. In Greek, the Hellenistic poet Nossis was described by Marylin B. Skinner as an imitator of Sappho, and Kathryn Gutzwiller argues that Nossis explicitly positioned herself as an inheritor of Sappho's position as a woman poet.[133] Beyond poetry, Plato cites Sappho in his Phaedrus, and Socrates' second speech on love in that dialogue appears to echo Sappho's descriptions of the physical effects of desire in fragment 31.[134] In the first century BC, Catullus established the themes and metres of Sappho's poetry as a part of Latin literature, adopting the Sapphic stanza, believed in antiquity to have been invented by Sappho,[135] giving his lover in his poetry the name "Lesbia" in reference to Sappho,[136] and adapting and translating Sappho's 31st fragment in his poem 51.[137][138]

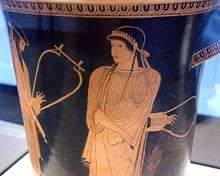

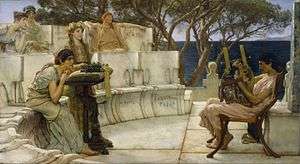

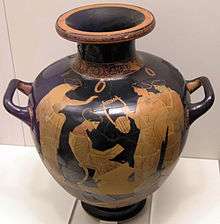

Other ancient poets wrote about Sappho's life. She was a popular character in ancient Athenian comedy,[45] and at least six separate comedies called Sappho are known.[139][lower-alpha 11] The earliest known ancient comedy to take Sappho as its main subject was the early-fifth or late-fourth century BC Sappho by Ameipsias, though nothing is known of it apart from its name.[140] Sappho was also a favourite subject in the visual arts, the most commonly depicted poet on sixth and fifth-century Attic red-figure vase paintings,[135] and the subject of a sculpture by Silanion.[141]

From the fourth century BC, ancient works portray Sappho as a tragic heroine, driven to suicide by her unrequited love for Phaon.[48] For instance, a fragment of a play by Menander says that Sappho threw herself off of the cliff at Leucas out of her love for Phaon.[142] Ovid's Heroides 15 is written as a letter from Sappho to her supposed love Phaon, and when it was first rediscovered in the 15th century was thought to be a translation of an authentic letter of Sappho's.[143] Sappho's suicide was also depicted in classical art, for instance on a first-century BC basilica in Rome near the Porta Maggiore.[142]

While Sappho's poetry was admired in the ancient world, her character was not always so well considered. In the Roman period, critics found her lustful and perhaps even homosexual.[144] Horace called her "mascula Sappho" in his Epistles, which the later Porphyrio commented was "either because she is famous for her poetry, in which men more often excel, or because she is maligned for having been a tribad".[145] By the third century AD, the difference between Sappho's literary reputation as a poet and her moral reputation as a woman had become so significant that the suggestion that there were in fact two Sapphos began to develop.[146] In his Historical Miscellanies, Aelian wrote that there was "another Sappho, a courtesan, not a poetess".[147]

Modern reception

By the medieval period, Sappho's works had been lost, though she was still known through later ancient authors such as Ovid. Her works began to become accessible again in the sixteenth century, first in early printed editions of authors who had quoted her. In 1508 Aldus Manutius printed an edition of Dionysius of Hallicarnassus, which contained Sappho 1, the "Ode to Aphrodite", and the first printed edition of Longinus' On the Sublime, complete with his quotation of Sappho 31, appeared in 1554. In 1566, the French printer Robert Estienne produced an edition of the Greek lyric poets which contained around 40 fragments attributed to Sappho.[148] In 1652, the first English translation of a poem by Sappho was published, in John Hall's translation of On the Sublime. In 1681 Anne Le Fèvre's French edition of Sappho made her work even more widely known.[149] Theodor Bergk's 1854 edition became the standard edition of Sappho in the second half of the 19th century;[150] in the first part of the 20th, the papyrus discoveries of new poems by Sappho led to editions and translations by Edwin Marion Cox and John Maxwell Edmonds, and culminated in the 1955 publication of Edgar Lobel's and Denys Page's Poetarum Lesbiorum Fragmenta.[151]

Like the ancients, modern critics have tended to consider Sappho's poetry "extraordinary".[152] As early as the 9th century, Sappho was referred to as a talented woman poet,[135] and in works such as Boccaccio's De Claris Mulieribus and Christine de Pisan's Book of the City of Ladies she gained a reputation as a learned lady.[153] Even after Sappho's works had been lost, the Sapphic stanza continued to be used in medieval lyric poetry,[135] and with the rediscovery of her work in the Renaissance, she began to increasingly influence European poetry. In the 16th century, members of La Pléiade, a circle of French poets, were influenced by her to experiment with Sapphic stanzas and with writing love-poetry with a first-person female voice.[135] From the Romantic era, Sappho's work – especially her "Ode to Aphrodite" – has been a key influence of conceptions of what lyric poetry should be.[154] Such influential poets as Alfred Lord Tennyson in the nineteenth century, and A. E. Housman in the twentieth, have been influenced by her poetry. Tennyson based poems including "Eleanore" and "Fatima" on Sappho's fragment 31,[155] while three of Housman's works are adaptations of the Midnight poem, long thought to be by Sappho though the authorship is now disputed.[156] At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Imagists – especially Ezra Pound, H. D., and Richard Aldington – were influenced by Sappho's fragments; a number of Pound's poems in his early collection Lustra were adaptations of Sapphic poems, while H. D.'s poetry was frequently Sapphic in "style, theme or content", and in some cases, such as "Fragment 40" more specifically invoke Sappho's writing.[157]

It was not long after the rediscovery of Sappho that her sexuality once again became the focus of critical attention. In the early seventeenth century, John Donne wrote "Sapho to Philaenis", returning to the idea of Sappho as a hypersexual lover of women.[159] The modern debate on Sappho's sexuality began in the 19th century, with Welcker publishing, in 1816, an article defending Sappho from charges of prostitution and lesbianism, arguing that she was chaste[135] – a position which would later be taken up by Wilamowitz at the end of the 19th and Henry Thornton Wharton at the beginning of the 20th centuries.[160] Despite attempts to defend her good name, in the nineteenth century Sappho was co-opted by the Decadent Movement as a lesbian "daughter of de Sade", by Charles Baudelaire in France and later Algernon Charles Swinburne in England.[161] By the late 19th century, lesbian writers such as Michael Field and Amy Levy became interested in Sappho for her sexuality,[162] and by the turn of the twentieth century she was a sort of "patron saint of lesbians".[163]

From the 19th century, Sappho began to be regarded as a role model for campaigners for women's rights, beginning with works such as Caroline Norton's The Picture of Sappho.[135] Later in that century, she would become a model for the so-called New Woman – independent and educated women who desired social and sexual autonomy –[164] and by the 1960s, the feminist Sappho was – along with the hypersexual, often but not exclusively lesbian Sappho – one of the two most important cultural perceptions of Sappho.[165]

The discoveries of new poems by Sappho in 2004 and 2014 excited both scholarly and media attention.[18] The announcement of the Tithonus poem was the subject of international news coverage, and was described by Marylin Skinner as "the trouvaille of a lifetime".[102][166]

See also

- Ancient Greek literature

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 7 – papyrus preserving Sappho fr. 5

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1231 – papyrus preserving Sappho frr. 15–30

Notes

- ↑ The fragments of Sappho's poetry are conventionally referred to by fragment number, though some also have one or more common names. The most commonly used numbering system is that of E. M. Voigt, which in most cases matches the older Lobel-Page system. Unless otherwise specified, the numeration in this article is from Diane Rayor and André Lardinois' Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, which uses Voigt's numeration with some variations to account for the fragments of Sappho discovered since Voigt's edition was published.

- ↑ The oldest of the testimonia are four Attic vase-paintings depicting Sappho, that are from the late sixth and early fifth centuries BC.

- ↑ According to the Suda she was from Eresos rather than Mytilene;[14] most testimonia and some of Sappho's own poetry point to Mytilene.[15]

- ↑ Strabo says that she was a contemporary of Alcaeus and Pittacus; Athenaeus that she was a contemporary of Alyattes, king of Lydia. The Suda says that she was active during the 42nd Olympiad, while Eusebius says that she was famous by the 45th Olympiad.[17]

- ↑ Two in the Oxyrhynchus Biography (P.Oxy. 1800), seven more in the Suda, and one in a scholion on Pindar.[19]

- ↑ Σκαμανδρώνυμος in Greek. Given as Sappho's father in the Oxyrhynchus Biography, Suda, a scholion on Plato's Phaedrus, and Aelian's Historical Miscellany, and as Charaxos' father in Herodotus.[19]

- ↑ Other sources say that Charaxus' lover was called Doricha, rather than Rhodopis.[34]

- ↑ The adjective sapphic, which means "relating to lesbians and/or lesbianism", and the related words sapphist, sapphism etc. all also come from Sappho.

- ↑ Though the word "élite" is used as a shorthand for a particular ideological tradition within Archaic Greek poetic thought, it is highly likely that all Archaic poets in fact were part of the elite, both by birth and wealth.[113]

- ↑ M.L. West comments on the translation of this word, "'Loveliness' is an inadequate translation of habrosyne, but I have not found an adequate one. Sappho does not mean 'elegance' or 'luxury'".[118]

- ↑ Parker lists plays by Ameipsias, Amphis, Antiphanes, Diphilos, Ephippus, and Timocles, along with two plays called Phaon, four called Leucadia, one Leukadios, and one Antilais all of which may have been about Sappho.

References

- ↑ Ohly 2002, p. 48.

- ↑ Freeman 2016, p. 8.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 2-9.

- ↑ McClure 2002, p. 38.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 2.

- ↑ Barnstone 2009, p. 123.

- ↑ Winkler 1990, p. 168.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 321.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 5.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. xi & 2.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 1.

- 1 2 Hutchinson 2001, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 4.

- ↑ Hutchinson 2001, p. 140, n.1.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. xi.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, pp. x–xi.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mendelsohn 2015.

- 1 2 Yatromanolakis 2008, ch. 4.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 20.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. 15, n.1.

- ↑ Sappho, frr. 1.20, 65.5, 94.5, 133b

- ↑ Smyth 1963, p. 233.

- ↑ Richter 1965, p. 172.

- ↑ Campbell & 1982, testimonia 1.

- ↑ Alcaeus fr. Loeb/L.P. 384. See n. 1 ad loc for an expression of the editor's uncertainty.

- 1 2 Campbell 1982, p. 3.

- ↑ Liddell et al. 1968, p. 832.

- ↑ Burn, A. R. (1968). The lyric age of Greece. Minerva Press. p. 227.

- ↑ Smyth 1963, p. 229.

- 1 2 Lidov 2002, pp. 205–6, n.7.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, pp. xi, 189.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, pp. 15, 187.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories, 2.135

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 3.

- 1 2 Hallett 1982, p. 22.

- ↑ Hallett 1982, pp. 22–23.

- 1 2 Parker 1993, p. 309.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. 9.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 10.

- ↑ Kurke 2007, p. 158.

- ↑ Hallett 1979, pp. 448–449.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 15.

- 1 2 Most 1995, p. 17.

- ↑ P. Oxy. xv, 1800, fr. 1

- ↑ Page 1959, p. 142.

- 1 2 Hallett 1979, p. 448.

- ↑ Lardinois 2014, p. 15.

- ↑ Gubar 1984, p. 44.

- ↑ DeJean 1989, p. 319.

- ↑ Most 1995, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Most 1995, p. 27.

- ↑ Devereux 1970.

- ↑ Klinck 2005, p. 194.

- ↑ Boehringer 2014, p. 151.

- ↑ Lardinois 2014, p. 30.

- ↑ duBois 1995, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 Yatromanolakis 2009, p. 216.

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 2009, pp. 216–218.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 310.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 313.

- ↑ Parker 1993, pp. 314–315.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 15.

- ↑ Page 1959, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Campbell 1967, p. 261.

- ↑ Parker 1993, pp. 314–316.

- 1 2 Parker 1993, p. 316.

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 2009, p. 218.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 342.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 343.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 344.

- 1 2 3 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 8.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. xii.

- 1 2 Bierl & Lardinois 2016, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Bolling 1961, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 Winkler 1990, p. 166.

- ↑ de Kreij 2015, p. 28.

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 1999, p. 180, n.4.

- 1 2 Yatromanolakis 1999, p. 181.

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 1999, p. 184.

- ↑ Lidov 2011.

- ↑ Obbink 2016, p. 42.

- ↑ Clayman 2011.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, pp. 81–2.

- 1 2 Reynolds 2001, p. 81.

- ↑ Tzetzes, On the Metres of Pindar 20–22 = T. 61

- 1 2 Reynolds 2001, p. 18.

- ↑ Grafton, Most & Settis 2010, p. 858.

- 1 2 Williamson 1995, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Haarman 2014, p. 164.

- ↑ Woodard 2008, p. 50-52.

- 1 2 Williamson 1995, p. 41.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 85.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 148.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ West 2005, p. 1.

- ↑ Obbink 2011.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 289.

- 1 2 Skinner 2011.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 155.

- ↑ Burn 1960, p. 229.

- ↑ duBois 1995, p. 6.

- ↑ duBois 1995, p. 7.

- ↑ Campbell 1967, p. 262.

- ↑ Zellner 2008, p. 435.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 66.

- ↑ Zellner 2008, p. 439.

- ↑ Zellner 2008, p. 438.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 73.

- ↑ Kurke 2007, p. 152.

- ↑ Kurke 2007, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Sappho 2.14–16

- ↑ Sappho 58.15

- ↑ Kurke 2007, p. 150.

- ↑ West 2005, p. 7.

- 1 2 duBois 1995, pp. 176–7.

- ↑ Rose 1960, p. 95.

- ↑ Cairns 1972, p. passim.

- ↑ Hallett 1979, p. 447.

- ↑ AP 7.407 = T 58

- ↑ Gosetti-Murrayjohn 2006, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ AP 7.14 = T 27

- ↑ Gosetti-Murrayjohn 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ AP 9.506 = T 60

- ↑ Gosetti-Murrayjohn 2006, p. 32.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 312.

- ↑ Parker 1993, p. 340.

- ↑ Aelian, quoted by Stobaeus, Anthology 3.29.58 = T 10

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 2009, p. 221.

- ↑ Gosetti-Murrayjohn 2006, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ duBois 1995, pp. 85–6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Schlesier 2015.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 72.

- ↑ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 108.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 30.

- ↑ Parker 1993, pp. 309–310, n. 2.

- ↑ Yatromanolakis 2008, ch. 1.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 69.

- 1 2 Hallett 1979, p. 448, n. 3.

- ↑ Most 1995, p. 19.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 73.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, pp. 72–3.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, pp. 73–4.

- ↑ Aelian, Historical Miscellanies 12.19 = T 4

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 84.

- ↑ Wilson 2012, p. 501.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 229.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 337.

- ↑ Hallett 1979, p. 449.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, pp. 82–3.

- ↑ Kurke 2007, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Peterson 1994, p. 123.

- ↑ Sanford 1942, pp. 223–4.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, pp. 310–312.

- ↑ Johannides 1983, p. 20.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, pp. 85–6.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 295.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, pp. 231–2.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 261.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 294.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, pp. 258–9.

- ↑ Reynolds 2001, p. 359.

- ↑ Payne 2014.

Works cited

- Barnstone, Willis (ed.) (2009). The Complete Poems of Sappho. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 9780834822009.

- Boehringer, Sandra (2014). "Female Homoeroticism". In Hubbard, Thomas K. A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Bierl, Anton; Lardinois, André (2016). "Introduction". In Bierl, Anton; Lardinois, André. The Newest Sappho: P. Sapph. Obbink and P. GC inv. 105, frs.1–4. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31483-2.

- Bolling, George Melville (1961). "Textual Notes on the Lesbian Poets". The American Journal of Philology. 82 (2).

- Burn, A. R. (1960), The Lyric Age of Greece, New York City, New York: St Martin's Press

- Cairns, Francis (1972). Generic Composition in Greek and Roman Poetry. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. passim.

- Campbell, D. A. (1967). Greek lyric poetry: a selection of early Greek lyric, elegiac and iambic poetry.

- Campbell, D. A. (ed.) (1982). Greek Lyric 1: Sappho and Alcaeus (Loeb Classical Library No. 142). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. ISBN 0-674-99157-5.

- Clayman, Dee (2011). "The New Sappho in a Hellenistic Poetry Book". Classics@. 4.

- DeJean, Joan (1989). Fictions of Sappho: 1546–1937. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- de Kreij, Mark (2015). "Transmissions and Textual Variants: Divergent Fragments of Sappho's Songs Examined". In Lardinois, André; Levie, Sophie; Hoeken, Hans; Lüthy, Christoph. Texts, Transmissions, Receptions: Modern Approaches to Narratives. Leiden: Brill.

- Devereux, George (1970). The Nature of Sappho's Seizure in Fr. 31 LP as Evidence of Her Inversion. The Classical Quarterly. 20.

- duBois, Page (1995). Sappho Is Burning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-16755-0.

- Freeman, Philip (2016). The Lost Songs and World of the First Woman Poet. New York City, New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393242232.

- Gosetti-Murrayjohn, Angela (2006). "Sappho as the Tenth Muse in Hellenistic Epigram". Arethusa. 39 (1).

- Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (2010). The Classical Tradition. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0.

- Gubar, Susan (1984). "Sapphistries". Signs. 10 (1): 43. doi:10.1086/494113.

- Haarman, Harold (2014), Roots of Ancient Greek Civilization: The Influence of Old Europe, Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarlane & Company, Inc. Publishers, ISBN 978-1-4766-1589-9

- Hallett, Judith P. (1979). "Sappho and her Social Context: Sense and Sensuality". Signs. 4 (3): 447. doi:10.1086/493630.

- Hallett, Judith P. (1982). "Beloved Cleïs". Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica. 10.

- Hutchinson, G. O. (2001). Greek Lyric Poetry: A Commentary on Selected Larger Pieces. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924017-5.

- Johannides, P. (1983), The Drawings of Raphael: With a Complete Catalogue, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, p. 20, ISBN 0-520-05087-8

- Klinck, Anne L. (2005). "Sleeping in the Bosom of a Tender Companion". Journal of Homosexuality. 49 (3–4): 193–208. doi:10.1300/j082v49n03_07. PMID 16338894.

- Kurke, Leslie V. (2007). "Archaic Greek Poetry". In Shapiro, H.A. The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lardinois, André (2014) [1989]. "Lesbian Sappho and Sappho of Lesbos". In Bremmer, Jan. From Sappho to De Sade: Moments in the History of Sexuality. London: Routledge.

- Liddell, Henry; Scott, Robert; Jones, Henry Stuart; McKenzie, Roderick (1968) [1843], A Greek-English Lexicon, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0 19 864214 8

- Lidov, Joel (2002). "Sappho, Herodotus and the Hetaira". Classical Philology. 97 (3).

- Lidov, Joel (2011). "The Meter and Metrical Style of the New Poem". Classics@. 4.

- McClure, Laura K. (2002), Sexuality and Gender in the Classical World: Readings and Sources, Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers, p. 38, ISBN 0-631-22589-7

- Mendelsohn, Daniel (16 March 2015). "Girl, Interrupted: Who Was Sappho?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Most, Glenn W. (1995). "Reflecting Sappho". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 40.

- Obbink, Dirk (2011). "Sappho Fragments 58–59: Text, Apparatus Criticus, and Translation". Classics@. 4.

- Obbink, Dirk (2016). "Ten Poems of Sappho: Provenance, Authority, and Text of the New Sappho Papyri". In Bierl, Anton; Lardinois, André. The Newest Sappho: P. Sapph. Obbink and P. GC inv. 105, frs.1–4. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31483-2.

- Ohly, Dieter (2002) [1972], The Munich Glyptothek: Greek and Roman Sculpture: A Brief Guide by Dieter Ohly with 75 Illustrations, Munich, Germany: Verlag C. H. Beck München, p. 48, ISBN 3-406-48355-0

- Parker, Holt (1993). "Sappho Schoolmistress". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 123.

- Page, D. L. (1959). Sappho and Alcaeus. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Payne, Tom (30 January 2014). "A new Sappho poem is more exciting than a new David Bowie album". The Telegraph. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Peterson, Linda H. (1994). "Sappho and the Making of Tennysonian Lyric". ELH. 61 (1).

- Rayor, Diane; Lardinois, André (2014). Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02359-8.

- Reynolds, Margaret, ed. (2001). The Sappho Companion. London: Vintage. ISBN 9780099738619.

- Richter, Gisela M. A. (1965). The Portraits of the Greeks. 1. London: Phaidon Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0801416835.

- Rose, H. J. (1960). A Handbook of Greek Literature. New York: E. F. Dutton. p. 95.

- Sanford, Eva Matthews (1942). "Classical Poets in the Work of A. E. Housman". The Classical Journal. 37 (4).

- Schlesier, Renate (2015). "Sappho". Brill's New Pauly Supplements II – Volume 7: Figures of Antiquity and Their Reception in Art, Literature, and Music. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- Skinner, Marilyn B. (2011). "Introduction". Classics@. 4.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1963) [1900], Greek Melic Poets, New York: Biblo and Tannen

- West, Martin. L. (2005). "The New Sappho". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 151.

- Wilson, Penelope (2012). "Women Writers and the Classics". In Hopkins, David; Martindale, Charles. The Oxford History of Classical Reception in English Literature: Volume 3 (1660-1790). ISBN 9780199219810.

- Williamson, Margaret (1995), Sappho's Immortal Daughters, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-78912-1

- Winkler, John J. (1990). The Constraints of Desire: The Anthropology of Sex and Gender in Ancient Greece. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415901235.

- Woodard, Roger D. (2008). The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521684958.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (1999). "Alexandrian Sappho Revisited". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 99.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (2008). Sappho in the Making: the Early Reception. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674026865.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (2009). "Alcaeus and Sappho". In Budelmann, Felix. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Lyric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139002479.

- Zellner, Harold (2008). "Sappho's Sparrows". The Classical World. 101 (4).

Further reading

- Balmer, Josephine (1992) Sappho: Poems and Fragments. Bloodaxe.

- Barnard, Mary (2000) Sappho: A New Translation. University of California Press.

- Burris, Simon; Fish, Jeffrey; Obbink, Dirk (2014). "New Fragments of Book 1 of Sappho". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 189.

- Carson, Anne (2002). If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-375-41067-8.

- Duban, Jeffrey M. (1983). Ancient and Modern Images of Sappho: Translations and Studies in Archaic Greek love Lyric. University Press of America.

- Greene, Ellen, ed. (1996). Reading Sappho. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lobel, E.; Page, D. L., eds. (1955). Poetarum Lesbiorum fragmenta. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Obbink, Dirk (2014). "Two New Poems By Sappho". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 189.

- Powell, Jim (2007) The Poetry Of Sappho Oxford University Press.

- Voigt, Eva-Maria (1971). Sappho et Alcaeus. Fragmenta. Amsterdam: Polak & van Gennep.

External links

| Library resources about Sappho |

| By Sappho |

|---|

- Commentaries on Sappho's fragments, William Annis.

- Fragments of Sappho, translated by Julia Dubnoff.

- Tithonus poem, text, translation by M. L. West, and notes by William Harris.

- Brothers poem, translation by Tim Whitmarsh.

- Sappho, BBC Radio 4, In Our Time.

- Sappho, BBC Radio 4, Great Lives.

- Works by Sappho at Project Gutenberg

-

-

- SORGLL: Sappho 1, read by Stephen G. Daitz

- Text of Sappho's poems with translations by Sean Palmer