Languages of Italy

| Languages of Italy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official languages | Italian |

| Regional languages | see "legal status" |

| Minority languages | see "legal status" |

| Main immigrant languages | Spanish, Albanian, Arabic, Romanian, Hungarian, and Romani |

| Main foreign languages | |

| Sign languages | Italian Sign Language |

| Common keyboard layouts | |

| Source | Special Eurobarometer, Europeans and their Languages, 2006 |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Italy |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

| Sport |

|

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

There are approximately thirty-four native living spoken languages and related dialects in Italy,[6] most of which are indigenous evolutions of Vulgar Latin, and are therefore classified as Romance languages. Although they are sometimes referred to as regional languages, there is no uniformity within any Italian region, and speakers from one locale within a region are typically aware of the features distinguishing their local tongue from the one of other places nearby. The official and most widely spoken language across the country is Standard Italian, a direct descendant of Tuscan.

Almost all the Romance languages native to Italy, with the notable exception of Italian, are often colloquially referred to as "dialects", although for some of them the term may coexist with other labels like "minority languages" or "vernaculars".[7] However, the use of the term "dialect" to refer to the languages of Italy may erroneously imply that the languages spoken in Italy are actual "dialects" of Standard Italian in the prevailing linguistic sense of "varieties or variations of a language".[8] This is not the case regarding the longstanding languages of Italy, as they are not varieties of Italian. Most of the local Romance languages of Italy predate Italian and evolved locally from Vulgar Latin, independently of what would become the national language, long before the fairly recent spread of Italian throughout Italy.[9] In fact, Standard Italian is itself either a continuation of, or a dialect heavily based on, Florentine Tuscan. The indigenous local Romance tongues of Italy are therefore classified as separate languages that evolved independently from Latin, rather than "dialects" or variations of the Italian language.[10][11] [12] Conversely, with the spread of Standard Italian throughout Italy in the 20th century, local varieties of Italian have also developed throughout the peninsula, influenced to varying extents by the underlying local languages, most noticeably at the phonological level; though regional boundaries seldom correspond to isoglosses distinguishing these varieties, these variations on Italians are commonly referred to as Regional Italian (italiano regionale).

There are several minority languages that belong to other Indo-European branches, such as Cimbrian (Germanic), Arbëresh (Albanian), the Slavomolisano dialect of Serbo-Croatian (Slavic), and Griko (Hellenic). Other non-indigenous languages are spoken by a substantial percentage of the population due to immigration.[13]

Legal status

Recognition at the European level

Italy is a signatory of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, but is yet to ratify the treaty, and therefore its provisions protecting regional languages do not apply in the country.[14]

The Charter does not, however, establish at what point differences in expression result in a separate language, deeming it an "often controversial issue", and citing the necessity to take into account, other than purely linguistic criteria, also "psychological, sociological and political considerations".[15]

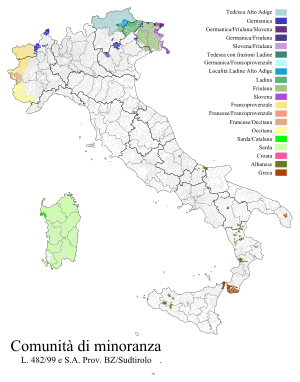

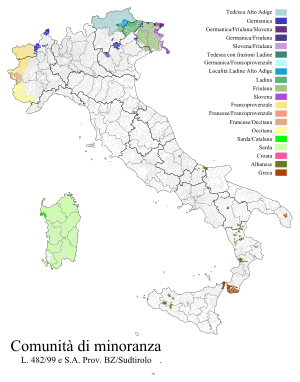

Recognition by the Italian state

The following minority languages are officially recognized as "historical language minorities" by the Law no. 482/1999: Albanian, Catalan, German, Greek, Slovene, Croatian, French, Franco-Provençal, Friulian, Ladin, Occitan and Sardinian (Legge 15 Dicembre 1999, n. 482, Art. 2, comma 1).[16] The selection of those languages to the exclusion of numerous others is a matter of some controversy.[17] Some interpretations of said law also state that the phrasing would seem to imply a further distinction, considering only some groups (namely Albanians, Catalans, Germanic peoples indigenous to Italy, Greeks, Slovenes and Croats) to be national minorities.[18][16] Nonetheless, the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, signed and ratified by Italy in 1997, applies to all the groups mentioned by the 1999 national law, with the addition of the Romani.

The original Italian Constitution does not explicitly express that Italian is the official national language. Since the constitution was penned there have been some laws and articles written on the procedures of criminal cases passed that explicitly state that Italian should be used:

- Statute of the Trentino-South Tyrol, (constitutional law of the northern region of Italy around Trento) – "[...] [la lingua] italiana [...] è la lingua ufficiale dello Stato." (Statuto Speciale per il Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Art. 99, "[...] [the language] Italian [...] is the official language of the State.")

- Code for civil procedure – "In tutto il processo è prescritto l'uso della lingua italiana. (Codice di procedura civile, Art. 122, "In all procedures, it is required that the Italian language is used.")

- Code for criminal procedure – "Gli atti del procedimento penale sono compiuti in lingua italiana." (Codice di procedura penale, Art. 109 [169-3; 63, 201 att.], "The acts of the criminal proceedings are carried out in the Italian language.")

- Article 1 of law 482/1999 – "La lingua ufficiale della Repubblica è l'italiano." (Legge 482/1999, Art. 1 Comma 1, "The official language of the Republic is Italian.")

Recognition by the regions

- Aosta Valley:

- Apulia:

- Griko, Arbëresh and Franco-Provençal are recognized and safeguarded (Legge regionale 5/2012)[21].

- Friuli-Venezia Giulia:

- Lombardy:

- Piedmont:

- Piedmontese is unofficial but recognised as the regional language (Consiglio Regionale del Piemonte, Ordine del Giorno n. 1118, Presentato il 30/11/1999);[25][26]

- the region "promotes", without recognising, the Occitan, Franco-Provençal, French and Walser languages (Legge regionale 7 aprile 2009, n. 11, Art. 1).[27]

- Sardinia:

- Sicily:

- South Tyrol:

- Trentino:

- Veneto:

Conservation status

.svg.png)

According to the UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, there are 31 endangered languages in Italy.[32] The degree of endangerment is classified in different categories ranging from 'safe' (safe languages are not included in the atlas) to 'extinct' (when there are no speakers left).[33]

The source for the languages' distribution is the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger[32] unless otherwise stated, and refers to Italy exclusively.

Vulnerable

- Alemannic: spoken in the Lys Valley of the Aosta Valley and in Northern Piedmont

- Bavarian: South Tyrol

- Ladin: several valleys, comunes and villages in the Dolomites, including the Val Badia and the Gardena Valley in South Tyrol, the Fascia Valley in Trentino, and Livinallongo in the Province of Belluno

- Sicilian: Sicily, southern and central Calabria and southern Apulia

- Neapolitan: Campania, Basilicata, Abruzzo, Molise, northern Calabria, northern and central Apulia, southern Lazio and Marche as well as eastern fringes of Umbria

- Romanesco: Metropolitan City of Rome in Lazio and in some comunes of southern Tuscany

- Venetian: Veneto, parts of Friuli-Venezia Giulia

Definitely endangered

- Algherese Catalan: the town of Alghero in northwestern Sardinia; an outlying dialect of Catalan language not listed separately by the SIL

- Alpine Provençal: the upper valleys of Piedmont (Val Mairo, Val Varacho, Val d’Esturo, Entraigas, Limoun, Vinai, Pinerolo, Sestrieres); the original joint ISO code [prv] for Alpine Provençal and Provençal has been retired on false grounds.

- Arbëresh: (i) Adriatic zone: Montecilfone, Campomarino, Portocannone and Ururi in Molise as well as Chieuti and Casalvecchio di Puglia in Apulia; (ii) San Marzano in Apulia; (iii) Greci in Campania; (iv) northern Basilicata: Barile, Ginestra and Maschito; (v) North Calabrian zone: ca. 30 settlements in northern Calabria (Plataci, Civita, Frascineto, San Demetrio Corone, Lungro, Acquaformosa etc.) as well as San Costantino Albanese and San Paolo Lucano in southern Basilicata; (vi) settlements in southern Calabria, e.g. San Nicola dell'Alto and Vena di Maida; (vii) Sicilian zone: Piana degli Albanesi and two nearby villages near Palermo; (viii) formerly also Villabadessa in Abruzzi; an outlying dialect of Albanian

- Cimbrian: vigorously spoken in Luserna in Trentino; disappearing in Giazza (part of the commune Selva di Progno) in the Province of Verona and in Roana in the Province of Vicenza; recently extinct in several other locations in the region; an outlying dialect of Bavarian

- Corsican: spoken on Maddalena Island off the northeast coast of Sardinia

- Emilian-Romagnol: Emilia-Romagna, parts of the provinces of Pavia, Voghera, and Mantua in southern Lombardy, the Lunigiana district in northwestern Tuscany, the Alta Valle del Tevere district in northern part of the Province of Perugia and eastern part of the Province of Arezzo, the Province of Pesaro-Urbino in the Marche, and in a zone called Traspadana Ferrarese in the Province of Rovigo in Veneto

- Faetar: Faeto and Celle San Vito in the Province of Foggia in Apulia; an outlying dialect of Francoprovençal not listed separately by the SIL

- Franco-Provençal: the Alpine valleys to the north and east of the Susa Valley in Piedmont; disappeared in France and Switzerland

- Friulian: Friuli-Venezia Giulia except the Province of Trieste and western and eastern border regions, and Portogruaro area in the Province of Venice in Veneto

- Gallo-Italic of Sicily: Nicosia, Sperlinga, Piazza Armerina, Valguarnera Caropepe and Aidone in the province of Enna, and San Fratello, Acquedolci, San Piero Patti, Montalbano Elicona, Novara di Sicilia and Fondachelli-Fantina in the province of Messina; an outlying dialect of Lombard not listed separately by the SIL; other dialects were formerly also spoken in southern Italy outside Sicily, especially in Basilicata

- Gallurese: northeastern Sardinia; an outlying dialect of Corsican

- Ligurian: Liguria and adjacent areas of Piedmont, Emilia and Tuscany; settlements in the towns of Carloforte on the San Pietro Island and Calasetta on the Sant’Antioco Island off the southwest coast of Sardinia

- Lombard: Lombardy (except the southernmost border areas) and the Province of Novara in Piedmont

- Mòcheno: Palù, Fierozzo and Frassilongo in the Fersina Valley in Trentino; an outlying dialect of Bavarian

- Piedmontese: Piedmont except the Province of Novara, the western Alpine valleys and southern border areas, as well as minor adjacent areas

- Resian: Resia in the northeastern part of the Province of Udine; an outlying dialect of Slovene not listed separately by the SIL

- Romani: spoken by the Roma community in Italy

- Sardinian, consisting of both the Campidanese (southern Sardinia) and Logudorese (central Sardinia) dialects

- Sassarese: northwestern Sardinia; a transitional language between Corsican and Sardinian

- Yiddish: spoken by parts of the Jewish community in Italy

Severely endangered

- Walser German: the village of Issime in the upper Lys Valley/Lystal in the Aosta Valley; an outlying dialect of Alemannic not listed separately by the SIL

- Molise Croatian: the villages of Montemitro, San Felice del Molise, and Acquaviva Collecroce in the Province of Campobasso in southern Molise;[34] a mixed Chakavian–Shtokavian dialect of Serbo-Croatian not listed separately by the SIL

- Griko (Salento): the Salento peninsula in the Province of Lecce in southern Apulia; an outlying dialect of Greek not listed separately by the SIL

- Gardiol: Guardia Piemontese in Calabria; an outlying dialect of Alpine Provençal

- Griko (Calabria): a few villages near Reggio di Calabria in southern Calabria; an outlying dialect of Greek not listed separately by the SIL

- Vastese: the town of Vasto.

Classification

All living languages indigenous to Italy are part of the Indo-European language family. The source is the SIL's Ethnologue unless otherwise stated.[35] Language classification can be a controversial issue, when a classification is contested by academic sources, this is reported in the 'notes' column.

They can be divided into Romance languages and non-Romance languages.

Romance languages

Gallo-Rhaetian and Ibero-Romance

| Language | Family | ISO 639-3 | Dialects spoken in Italy | Notes | Speakers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French | Gallo-Romance | Gallo-Rhaetian | Oïl | French | fra | 100,000 | ||

| Arpitan | Gallo-Romance | Gallo-Rhaetian | Oïl | Southeastern | frp | 70,000 | ||

| Friulian | Gallo-Romance | Gallo-Rhaetian | Rhaetian | fur | 600,000[36] | |||

| Ladin | Gallo-Romance | Gallo-Rhaetian | Rhaetian | lld | 31,000 | |||

| Catalan | Ibero-Romance | East Iberian | cat | Algherese | 20,000 | |||

| Occitan | Ibero-Romance | Oc | oci | Provençal; Gardiol | 100,000 | |||

Gallo-Italic languages

| Language | ISO 639-3 | Dialects spoken in Italy | Notes | Speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emiliano-Romagnolo | eml | Emilian; Romagnol (Forlivese); | Emilian and Romagnol have been assigned two different ISO 639-3 codes (egl and rgn, respectively). | 1,000,000 |

| Ligurian | lij | Tabarchino; Mentonasc; Intemelio; Brigasc | 500,000 | |

| Lombard | lmo | Western Lombard (see Western dialects of Lombard language); Eastern Lombard; Gallo-Italic of Sicily | 3,600,000 | |

| Piedmontese | pms | 1,600,000 | ||

| Venetian | vec | Triestine; Fiuman; Chipilo Venetian; Talian; veneziano Lagunar | Usually not considered as being Gallo-Italic | 3,800,000 |

Italo-Dalmatian languages

Not included is Corsican, which is mainly spoken on the French island of Corsica. Istriot is only spoken in Croatia. Judeo-Italian is moribund.

| Language | ISO 639-3 | Dialects spoken in Italy | Notes | Speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian | ita | Tuscan; | National language | 60,000,000 |

| Central Italian | nap | Romanesco; Sabino; Marchigiano | 5,700,000 | |

| Neapolitan | ita | Abruzzese; Cosentino; Bari dialect | 3,000,000 | |

| Sicilian | scn | Salentino; Southern Calabrian | 4,700,000 |

Sardinian language

Sardinian is a distinct language group with significant phonological and lexical differences among its varieties. Ethnologue, not without controversy, even goes as far as considering Sardinian to be four separate languages, all being included along with Corsican and the Corso-Sardinian varieties in a hypothetical subgroup (Southern Romance[37]) which has gained little support from linguists. UNESCO, while seeming to share the same opinion of Ethnologue by calling Gallurese and Sassarese alternately "Sardinian",[32] considers them to be dialects of Corsican rather than Sardinian on the other hand.[32] As is not infrequently the case in such controversies, the linguistic landscape of Sardinia is in principle most accurately described as being, for the most part, a dialect continuum.

| Language | ISO 639-3 | Dialects spoken in Italy | Notes | Speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campidanese Sardinian | sro | Southern dialect of Sardinian proper | 500,000 | |

| Logudorese Sardinian | src | Central dialect of Sardinian proper | 500,000 | |

| Gallurese | sdn | Outlying dialect of Corsican | 100,000 | |

| Sassarese | sdc | Outlying dialect of Corsican | 100,000 |

Non-Romance languages

Albanian, Slavic, Greek and Romani languages

| Language | Family | ISO 639-3 | Dialects spoken in Italy | Notes | Speakers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arbëresh | Albanian | Tosk | aae | considered an outlying dialect of Albanian by the UNESCO[32] | 100,000 | |||

| Serbo-Croatian | Slavic | South | Western | hbs | Molise Croatian | 1,000 | ||

| Slovene | Slavic | South | Western | slv | Gai Valley dialect; Resian; Torre Valley dialect; Natisone Valley dialect; Brda dialect; Karst dialect; Inner Carniolan dialect; Istrian dialect | 100,000 | ||

| Italiot Greek | Hellenic (Greek) | Attic | ell | Griko (Salento); Calabrian Greek | 20,000 | |||

| Romani | Indo-Iranian | Indo-Aryan | Central Zone | Romani | rom | |||

High German languages

| Language | Family | ISO 639-3 | Dialects spoken in Italy | Notes | Speakers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German | Middle German | East Middle German | deu | Tyrolean dialects | Austrian German is the usual standard variety | 315,000 |

| Cimbrian | Upper German | Bavarian-Austrian | cim | sometimes considered a dialect of Bavarian, also considered an outlying dialect of Bavarian by the UNESCO[32] | 2,200 | |

| Mocheno | Upper German | Bavarian-Austrian | mhn | considered an outlying dialect of Bavarian by the UNESCO[32] | 1,000 | |

| Walser | Upper German | Alemannic | wae | 3,400 | ||

Geographic distribution

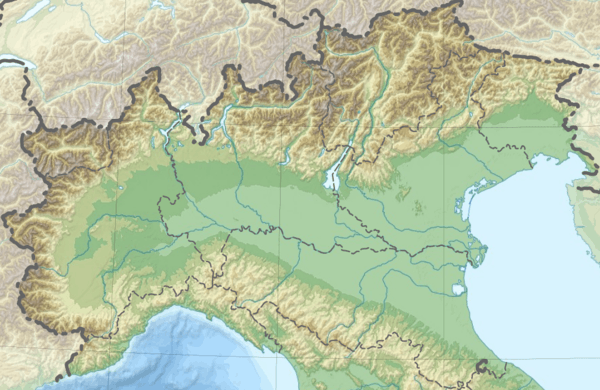

Northern Italy

The Northern Italian languages are conventionally defined as those Romance languages spoken north of the La Spezia–Rimini Line, which runs through the northern Apennine Mountains just to the north of Tuscany; however, the dialects of Occitan and Franco-Provençal spoken in the extreme northwest of Italy (e.g. the Valdôtain in the Aosta Valley) are generally excluded. The classification of these languages is difficult and not agreed-upon, due both to the variations among the languages and to the fact that they share isoglosses of various sorts with both the Italo-Romance languages to the south and the Gallo-Romance languages to the northwest.

One common classification divides these languages into four groups:

- The Italian Rhaeto-Romance languages, including Ladin and Friulan

- The poorly researched Istriot language

- The Venetian language (sometimes grouped with the majority Gallo-Italian languages)

- The Gallo-Italian languages, including all the rest (although with some doubt regarding the position of Ligurian)

Any such classification runs into the basic problem that there is a dialect continuum throughout northern Italy, with a continuous transition of spoken dialects between e.g. Venetian and Ladin, or Venetian and Emilio-Romagnolo (usually considered Gallo-Italian).

All of these languages are considered innovative relative to the Romance languages as a whole, with some of the Gallo-Italian languages having phonological changes nearly as extreme as standard French (usually considered the most phonologically innovative of the Romance languages). This distinguishes them significantly from standard Italian, which is extremely conservative in its phonology (and notably conservative in its morphology). [38]

Southern Italy and islands

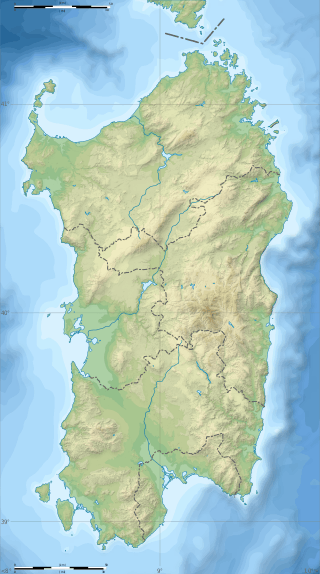

Approximate distribution of the regional languages of Sardinia and Southern Italy according to the UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger:

Mother tongues of foreigners

| Language (2012)[39][40] | Population |

|---|---|

| Romanian | 798,364 |

| Arabic | 476,721 |

| Albanian | 380,361 |

| Spanish | 255,459 |

| Italian | 162,148 |

| Chinese | 159,597 |

| Russian | 126,849 |

| Ukrainian | 119,883 |

| French | 116,287 |

| Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian | 93,289 |

| Polish | 87,283 |

| Others | 862,986 |

Standardised written forms

Although "[al]most all Italian dialects were being written in the Middle Ages, for administrative, religious, and often artistic purposes,"[41] use of local language gave way to stylized Tuscan, eventually labeled Italian. Local languages are still occasionally written, but only the following regional languages of Italy have a standardised written form. This may be widely accepted or used alongside more traditional written forms:

- Piedmontese: traditional, definitely codified between the 1920s and the 1960s by Pinin Pacòt and Camillo Brero

- Ligurian: "Grafîa ofiçiâ" created by the Académia Ligùstica do Brénno;[42]

- Sardinian: "Limba sarda comuna" was experimentally adopted in 2006;[43]

- Friulian: "Grafie uficiâl" created by the Osservatori Regjonâl de Lenghe e de Culture Furlanis;[44]

- Ladin: "Grafia Ladina" created by the Istituto Ladin de la Dolomites;[45]

- Venetian: "Grafia Veneta Unitaria", official manual from Regione Veneto local government published in 1995, although written in Italian.[46]

Gallery

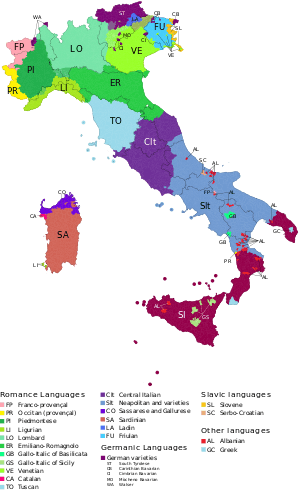

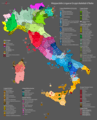

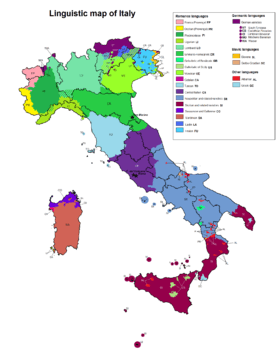

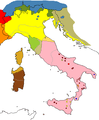

Languages of Italy

Languages of Italy Detailed map of the languages and language islands of Italy

Detailed map of the languages and language islands of Italy Regional languages of Italy according to Clemente Merlo and Carlo Tagliavini in 1939

Regional languages of Italy according to Clemente Merlo and Carlo Tagliavini in 1939 Main dialectal groups of Italy

Main dialectal groups of Italy Main linguistic groups of Italy

Main linguistic groups of Italy Officially recognised ethno-linguistic minorities of Italy

Officially recognised ethno-linguistic minorities of Italy Percentage of people in Italy having a command of a regional language (Doxa, 1982; Coveri's data, 1984)

Percentage of people in Italy having a command of a regional language (Doxa, 1982; Coveri's data, 1984).svg.png) Percentage of regional bilingualism in Italy (ISTAT, 2015).

Percentage of regional bilingualism in Italy (ISTAT, 2015).

See also

Notes

- ↑ Tagliavini, Carlo (1962). Le origini delle lingue neolatine: introduzione alla filologia romanza. R. Patròn.

- ↑ "La variazione diatopica". Archived from the original on February 2012.

- ↑ Archived 7 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ AIS, Sprach-und Sachatlas Italiens und der Südschweiz, Zofingen 1928-1940

- ↑ "Lingue di Minoranza e Scuola: Carta Generale". Minoranze-linguistiche-scuola.it. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Italy". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-07-22.

- ↑ Loporcaro 2009; Marcato 2007; Posner 1996; Repetti 2000:1–2; Cravens 2014.

- ↑ Cravens 2014

- ↑ Tullio, de Mauro (2014). Storia linguistica dell'Italia repubblicana: dal 1946 ai nostri giorni. Editori Laterza, EAN: 9788858113622

- ↑ Maiden, Martin; Parry, Mair (March 7, 2006). The Dialects of Italy. Routledge. p. 2.

- ↑ Repetti, Lori (2000). Phonological Theory and the Dialects of Italy. John Benjamins Publishing. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ Andreose, Alvise; Renzi, Lorenzo (2013), "Geography and distribution of the Romance Languages in Europe", in Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam, The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages, Vol. 2, Contexts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 302–308

- ↑ "Legge 482". Camera.it. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- ↑ "Chart of signatures and ratifications of Treaty 148". Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ↑ What is a regional or minority language?, Council of Europe, retrieved 2015-10-17

- 1 2 Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche, Italian parliament, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Cravens 2014

- ↑ Archived 16 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Legge 482". Webcitation.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- 1 2 Statut spécial de la Vallée d'Aoste, Title VIe, Region Vallée d'Aoste, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Puglia, QUIregione - Il Sito web Istituzionale della Regione. "QUIregione - Il Sito web Istituzionale della Regione Puglia". QUIregione - Il Sito web Istituzionale della Regione Puglia. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ↑ Norme per la tutela, valorizzazione e promozione della lingua friulana, Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Norme regionali per la tutela della minoranza linguistica slovena, Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ «L.R. 25/2016 - 1. Ai fini della presente legge, la Regione promuove la rivitalizzazione, la valorizzazione e la diffusione di tutte le varietà locali della lingua lombarda, in quanto significative espressioni del patrimonio culturale immateriale, attraverso: a) lo svolgimento di attività e incontri finalizzati a diffonderne la conoscenza e l'uso; b) la creazione artistica; c) la diffusione di libri e pubblicazioni, l'organizzazione di specifiche sezioni nelle biblioteche pubbliche di enti locali o di interesse locale; d) programmi editoriali e radiotelevisivi; e) indagini e ricerche sui toponimi. 2. La Regione valorizza e promuove tutte le forme di espressione artistica del patrimonio storico linguistico quali il teatro tradizionale e moderno in lingua lombarda, la musica popolare lombarda, il teatro di marionette e burattini, la poesia, la prosa letteraria e il cinema. 3. La Regione promuove, anche in collaborazione con le università della Lombardia, gli istituti di ricerca, gli enti del sistema regionale e altri qualificati soggetti culturali pubblici e privati, la ricerca scientifica sul patrimonio linguistico storico della Lombardia, incentivando in particolare: a) tutte le attività necessarie a favorire la diffusione della lingua lombarda nella comunicazione contemporanea, anche attraverso l'inserimento di neologismi lessicali, l'armonizzazione e la codifica di un sistema di trascrizione; b) l'attività di archiviazione e digitalizzazione; c) la realizzazione, anche mediante concorsi e borse di studio, di opere e testi letterari, tecnici e scientifici, nonché la traduzione di testi in lingua lombarda e la loro diffusione in formato digitale.»

- ↑ Ordine del Giorno n. 1118, Presentato il 30/11/1999, Consiglio Regionale del Piemonte, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Ordine del Giorno n. 1118, Presentato il 30/11/1999 (PDF), Gioventura Piemontèisa, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Legge regionale 7 aprile 2009, n. 11. (Testo coordinato) “Valorizzazione e promozione della conoscenza del patrimonio linguistico e culturale del Piemonte”, Consilio Regionale del Piemonte, retrieved 2017-12-02

- 1 2 Legge Regionale 15 ottobre 1997, n. 26, Regione Sardegna, 1997, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Gazzetta Ufficiale della Regione Siciliana - Anno 65° - Numero 24

- 1 2 Statuto speciale per il Trentino-Alto Adige (PDF), Regione.taa.it, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Legge regionale 13 aprile 2007, n. 8, Consiglio Regionale del Veneto, retrieved 2015-10-17

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, UNESCO's Endangered Languages Programme, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Degrees of endangerment, UNESCO's Endangered Languages Programme, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ "Endangered languages in Europe: report". Helsinki.fi. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- ↑ Languages of Italy, SIL, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ "Sociolinguistic Condition". Arlef.it. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Ethnologue report for Southern Romance". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- ↑ Hull, Geoffrey, PhD thesis 1982 (University of Sydney), published as The Linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia: Historical Grammar of the Padanian Language. 2 vols. Sydney: Beta Crucis, 2017.

- ↑ "Linguistic diversity among foreign citizens in Italy". Statistics of Italy. 25 July 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Stranieri residenti e condizioni di vita : Lingua madre". Istat.it. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Andreose, Alvise; Renzi, Lorenzo (2013), "Geography and distribution of the Romance Languages in Europe", in Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam, The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages, Vol. 2, Contexts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 303

- ↑ Grafîa ofiçiâ, Académia Ligùstica do Brénno, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Limba sarda comuna, Sardegna Cultura, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Grafie dal O.L.F., Friûl.net, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ PUBLICAZIOIGN DEL ISTITUTO LADIN, Istituto Ladin de la Dolomites, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ↑ Grafia Veneta Unitaria - Manuale a cura della giunta regionale del Veneto, Commissione regionale per la grafia veneta unitaria, retrieved 2016-12-06

References

- Loporcaro, Michele (2009). Profilo linguistico dei dialetti italiani (in Italian). Bari: Laterza.

- Cravens, Thomas D. (2014). "Italia Linguistica and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages". Forum Italicum. 48. pp. 202–218.

- Marcato, Carla (2007). Dialetto, dialetti e italiano (in Italian). Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Posner, Rebecca (1996). The Romance languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rapetti, Lori, ed. (2000). Phonological theory and the dialects of Italy. Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science, Series IV Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. 212. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

External links

- NavigAIS Online version of the Sprach- und Sachatlas Italiens und der Südschweiz (AIS) (Linguistic and Ethnographic Atlas of Italy and Southern Switzerland)

- An interactive map of languages and dialects in Italy

- Ethnologue - Languages of Italy

- Rivista Etnie, linguistica