Roman Italy

| Italy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4th/3rd century BC–476 AD | |||||||||

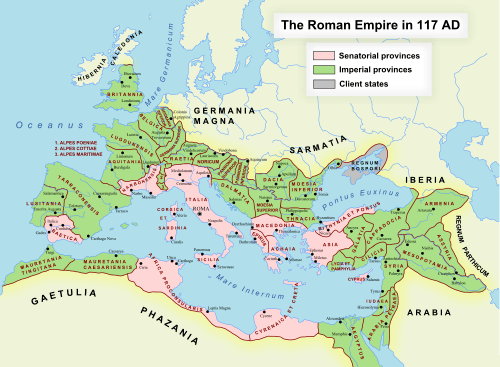

Roman Empire at its greatest extent | |||||||||

| Capital | Rome, Mediolanum and Ravenna (as capitals of the Republic or the Empire) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Latin | ||||||||

| Religion | Polytheistic synchretism, followed by monotheistic Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Mixed constitution | ||||||||

| Legislature | Senate and People of Rome | ||||||||

| Historical era | Classic Antiquity | ||||||||

• Legendary arrival of Aeneas in Italy | 11th century BC | ||||||||

| 4th/3rd century BC | |||||||||

| 90 BC | |||||||||

| 45 BC | |||||||||

• Augustan organization | 7 BC | ||||||||

• Deocletian organization | late 3rd century | ||||||||

• Constantine organization | 330 | ||||||||

| 476 AD | |||||||||

| 6th century AD | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• | 10-15 millions at its peak | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | IT | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||

Italia (Latin name for the Italian Peninsula) was the homeland of the Romans and the metropole of Rome's empire in classical antiquity. According to Roman mythology, Italy was the new home promised by Jupiter to Aeneas of Troy and his descendants, ancestors of the founders of Rome.

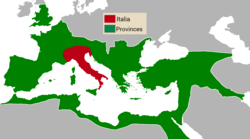

The consolidation of Italy into a single entity occurred during the Roman expansion in the peninsula, when Rome formed a permanent association with most of the local tribes and cities.[1] The strength of the Italian alliance was a crucial factor in the rise of Rome, starting with the Punic and Macedonian wars between the 3d and 2nd century BC. As provinces were being established throughout the Mediterranean, Italy maintained a special status which made it "not a province, but the Domina (ruler) of the provinces".[2] Such a status meant that Roman magistrates exercised the Imperium domi (police power) within Italy, rather than the Imperium militiae (military power) used abroad. Italy's inhabitants had latin rights as well as religious and financial privileges.

The period between the end of the 2nd century BC and the 1st century BC was turbolent, beginning with the Servile Wars, continuing with the opposition of aristocratic élite to reformers and even leading to a Social War in the middle of Italy. However, Roman citizenship was recognized to the Italics by the end of the conflict and then extended to Cisalpine Gaul when Julius Caesar became Roman dictator. Within the context of the transition from Republic to Principate, Italy swore allegiance to Octavian Augustus and was then organized in eleven regions from the Alps to the Ionian Sea, including Istria.

More than two centuries of stability followed, during which Italy was referred to as the rectrix mundi (queen of the world) and omnium terrarum parens (motherland of all lands).[3] The crisis of the third century hit Italy particularly hard and left the eastern half of the Empire more prosperous. Nevertheless, the islands of Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily and Malta were added to Italy by Diocletian in 292 AD, and Italian cities such as Milan and Ravenna continued to serve as capitals for the West. The Bishop of Rome gained importance during Constantine's reign and was given religious primacy with the Edict of Thessalonica under Theodosius I.

Italy was invaded several times by the barbarians and fell under the control of Odoacer, when Romulus Augustus was deposed in 476 AD. In the sixth century, Italy's territory was divided between the Byzantine Empire and the Germanic peoples. After that, Italy remained divided until 1861, when it was reunited in the Kingdom of Italy, which became the present-day Italian Republic in 1946.

Characteristics

Following the end of the Social War in 88 BC, Rome had allowed its Italian allies full rights in Roman society and granted Roman citizenship to all the Italic peoples.[4]

After having been for centuries the heart of the Roman Empire, from the 3rd century the government and the cultural center began to move eastward: first the Edict of Caracalla in 212 AD extended Roman citizenship to all free men within the imperial boundaries. Then, Christianity became the dominant religion during Constantine's reign (306–337), raising the power of other Eastern political centres. Although not founded as a capital city in 330, Constantinople grew in importance. It finally gained the rank of eastern capital when given an urban prefect in 359 and the senators who were clari became senators of the lowest rank as clarissimi.

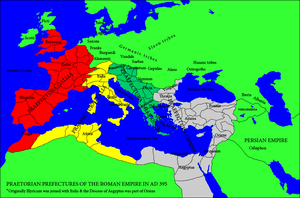

As a result, Italy began to decline in favour of the provinces, which resulted in the division of the Empire into two administrative units in 395: the Western Roman Empire, with its capital at Mediolanum (now Milan), and the Eastern Roman Empire, with its capital at Constantinople (now Istanbul). In 402, the capital was moved to Ravenna from Milan, confirming the decline of the city of Rome (which was sacked in 410 for the first time in seven centuries).

History

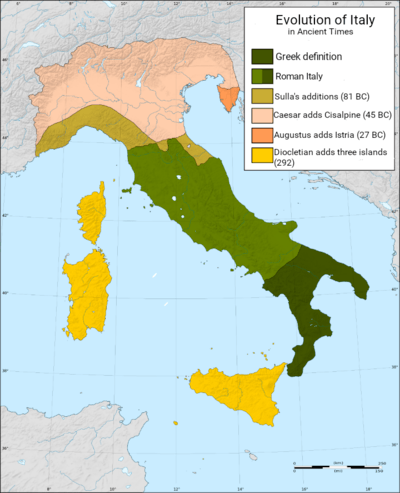

The name Italia covered an area whose borders evolved over time. According to Strabo's Geographica, before the expansion of the Roman Republic, the name was used by Greeks to indicate the land between the strait of Messina and the line connecting the gulf of Salerno and gulf of Taranto (corresponding roughly to the current region of Calabria); later the term was extended by Romans to include the Italian Peninsula up to the Rubicon, a river located between Northern and Central Italy.

In 49 BC, with the Lex Roscia, Julius Caesar gave Roman citizenship to the people of the Cisalpine Gaul;[5] while in 42 BCE the hitherto existing province was abolished, thus extending Italy to the north up to the southern foot of the Alps.[6][7]

Under Augustus, the peoples of today's Aosta Valley and of the western and northern Alps were subjugated (so the western border of Roman Italy was moved to the Varus river), and the Italian eastern border was brought to the Arsia in Istria;.[7] Finally, in the late 3rd century, Italy came to include the islands of Corsica and Sardinia and Sicily, as well as Raetia and part of Pannonia to the north.[8] The city of Emona (modern Ljubljana, Slovenia) was the easternmost town of Italy.

Augustan organization

At the beginning of the Roman imperial era, Italy was a collection of territories with different political statuses. Some cities, called municipia, had some independence from Rome, while others, the coloniae, were founded by the Romans themselves. Around 7 BC, Augustus divided Italy into eleven regiones, as reported by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia:

- Regio I Latium et Campania

- Regio II Apulia et Calabria

- Regio III Lucania et Bruttium

- Regio IV Samnium

- Regio V Picenum

- Regio VI Umbria et Ager Gallicus

- Regio VII Etruria

- Regio VIII Aemilia

- Regio IX Liguria

- Regio X Venetia et Histria

- Regio XI Transpadana

Italy was privileged by Augustus and his heirs, with the construction, among other public structures, of a dense network of Roman roads. The Italian economy flourished: agriculture, handicraft and industry had a sensible growth, allowing the export of goods to the other provinces. The Italian population may have grown as well: three census were ordered by Augustus, to record the number of Roman citizens throughout the empire. The surviving totals were 4,063,000 in 28 BC, 4,233,000 in 8 BC, and 4,937,000 in AD 14, but it is still debated whether these counted all citizens, all adult male citizens, or citizens sui iuris.[9] Estimates for the population of mainland Italy, including Cisalpine Gaul, at the beginning of the 1st century range from 6,000,000 according to Karl Julius Beloch in 1886, to 14,000,000 according to Elio Lo Cascio in 2009.[10]

Diocletian and Constantinian re-organizations

During the Crisis of the Third Century the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressures of invasions, military anarchy and civil wars, and hyperinflation. In 284, emperor Diocletian restored political stability. He carried out thorough administrative reforms to maintain order. He created the so-called Tetrarchy whereby the empire was ruled by two senior emperors called Augusti and two junior vice-emperors called Caesars. He decreased the size of the Roman provinces by doubling their number to reduce the power of the provincial governors; make their job easier and governance more effective by controlling a smaller areas. He may have grouped the provinces into several dioceses (Latin: diocesis) under the supervision of the imperial vicarius (vice, deputy) who were the head of the diocese (there is a move to place the creation of dioceses to the year 313/14 by Constantine and Licinius after their meeting in Milan in February 313. During the Crisis of the Third Century the importance of Rome declined because the city was far from the troubled frontiers. Diocletian and his colleagues usually resided in four imperial seats. The Augusti, Diocletian and Maximian, who were responsible for the East and West respectively, established themselves at Nicomedia, in north-western Anatolia (closer to the Persian frontier in the east) and Milan, in northern Italy (closer to the European frontiers) respectively. The seats of the Caesars were Augusta Treverorum (on the River Rhine frontier) for Constantius Chlorus and Sirmium (on the River Danube frontier) for Galerius who also resided at Thessaloniki.

Under Diocletian Italy became the Dioecesis Italiciana. It included Raetia. It was subdivided the following provinces:

- Liguria (today's Liguria and western Piedmont)

- Transpadana (western Piedmont and Lombardy)

- Rhaetia (eastern Switzerland, western and central Austria and part of southern Germany)

- Venetia et Histria (today's Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Trentino-Alto Adige)

- Aemilia (Emilia-Romagna)

- Tuscia (Etruria) et Umbria (Tuscany and Umbria)

- Flaminia (Picenum and the former Ager Gallicus, in today's Marche)

- Latium et Campania (the coastal parts of Lazio and Campania)

- Samnium (Abruzzo, Molise and Irpinia)

- Apulia et Calabria (today's Apulia)

- Lucania et Bruttium (Basilicata and Calabria)

- Sicilia (Sicily and Malta)

- Corsica et Sardinia

Constantine subdivided the empire into four Praetorian prefectures. The Diocesis Italiciana became the Praetorian prefecture of Italy (praefectura praetoria Italiae), and was subdivided into two dioceses. It still included Raetia. The two dioceses and their provinces were:

Diocesis Italia annonaria (Italy of the annona - its inhabitants had to provide the administration in Milan and the troops stationed in that city the annona - food, wine and timber).

- Alpes Cottiae (modern Liguria and part of Piedmont)

- Liguria (western Lombardy and part of Piedmont)

- Venetia et Histria (Istria [which is now part of Croatia, Slovenia and Italy], Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Trentino-Alto Adige, Veneto and eastern and central Lombardy)

- Raetia I (eastern Switzerland and western Austria)

- Rhaetia II (central Austria and part of southern Germany)

- Aemilia (the Emilia part of Emilia-Romagna)

- Flaminia et Picenum Annonarium (Romagna and northern Marche)

Diocesis Italia Suburbicaria (Italy "under the government of the urbs", i.e. Rome)

- Tuscia (Etruria) et Umbria (Tuscany, Umbria and the northern part of coastal Lazio)

- Picenum suburbicarium (Piceno, in southern Marche)

- Valeria Sabina (the modern province of Rieti, other areas of Lazio and areas of Umbria and Abruzzo)

- Campania (central and southern coastal Lazio and coastal Campania except for the modern province of Salerno)

- Samnium (Abruzzo, Molise and the mountain areas of modern Campania; i.e., the modern provinces of Benevento and Avellino and part of the province of Caserta)

- Apulia et Calabria (today's Apulia)

- Lucania et Bruttium (modern Calabria, Basilicata and the province of Salerno in modern Campania)

- Sicilia (Sicily and Malta)

- Sardinia

- Corsica

Western Roman Empire

In 330, Constantine inaugurated Constantinople. He established the imperial court, a Senate, financial and judicial administrations, as well as the military structures. The new city, however, did not receive an urban prefect until 359 which raised it to the status of eastern capital. After the death of Theodosius in 395 and the subsequent division of the empire Italy was part of the Western Roman Empire. As a result of Alaric's invasion in 402 the western seat was moved from Mediolanum to Ravenna. Alaric, king of Visigoths, sacked Rome itself in 410; something that hadn't happened for eight centuries. Northern Italy was attacked by Attila's Huns in 452. Rome was sacked in 455 again by the Vandals under the command of Genseric.

According to Notitia Dignitatum, one of the very few surviving documents of Roman government updated to the 420s, Roman Italy was governed by a praetorian prefect, Prefectus praetorio Italiae (who also governed the Diocese of Africa and the Diocese of Pannonia), one vicarius, and one comes rei militaris. The regions of Italy were governed at the end of the fourth century by eight consulares (Venetiae et Histriae, Aemiliae, Liguriae, Flaminiae et Piceni annonarii, Tusciae et Umbriae, Piceni suburbicarii, Campaniae, and Siciliae), two correctores (Apuliae et Calabriae and Lucaniae et Bruttiorum) and seven praesides (Alpium Cottiarum, Rhaetia Prima and Secunda, Samnii, Valeriae, Sardiniae, and Corsicae). After the assassination of Valentinian III in 455 the puppet emperors were controlled by the barbarian generals. The Western imperial government maintained control over Italy whose coasts were periodically under attack. In 476, with the abdication of Romulus Augustulus, the Western Roman Empire had formally fallen unless one considers Julius Nepos, the legitimate emperor recognized by Constantinople as the last. He was assassinated in 480: he was regarded as legitimate by Constantinople. He may have been recognized by Odoacer. Italy remained under Odoacer and his Kingdom of Italy, and then under the Ostrogothic Kingdom. The Germanic successor states under Odoacer and Theodoric the Great continued to use the Roman administrative machinery, as well as being nominal subjects of the Eastern emperor at Constantinople. In 535 Roman Emperor Justinian sent an army to retake Italy which suffered twenty years of disastrous war. In August 554, Justinian issued a Pragmatic sanction which maintained most of the organization of Diocletian. The "Prefecture of Italy" thus survived, and came under Roman control in the course of Justinian's Gothic War. As a result of the Lombard invasion in 568, the Byzantines lost most of Italy, except the territories of the Exarchate of Ravenna - a corridor from Venice to Lazio - and footholds in the south Naples and the toe and heel of the peninsula.

References

- ↑ Mommsen, Theodor (1855). History of Rome, Book II: From the Abolition of the Monarchy in Rome to the Union of Italy. Leipzig: Reimer & Hirsel.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Keaveney, Arthur (1987). Rome and the Unification of Italy. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 9781904675372.

- ↑ Cassius, Dio. Historia Romana. 41. 36.

- ↑ Laffi, Umberto (1992). "La provincia della Gallia Cisalpina". Athenaeum (in Italian). Firenze (80): 5–23.

- 1 2 Aurigemma, Salvatore. "Gallia Cisalpina". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Enciclopedia Italiana. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ↑ "Italy (ancient Roman territory)". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ Hin, Saskia (2007). Counting Romans (PDF). Leiden: Princeton/Stanford Working Papers.

- ↑ Lo Cascio, Elio (2009). Urbanization as a Proxy of Demographic and Economic Growth. Oxford: Scholarship Online. ISBN 9780199562596.

Further reading

- Potter, Timothy W. (1990). Roman Italy. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06975-7.

- Salmon, Edward T. (1982). The Making of Roman Italy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801414381.

- Whatmough, Joshua (1937). The Foundations of Roman Italy. London: Methuen & Company.

- Lomas, Kathryn (1996). Roman Italy, 338 BC-AD 200. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-16072-2.

- Launaro, Alessandro (2011). Peasants and Slaves: The Rural Population of Roman Italy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107004795.

- Hin, Saskia (2013). The Demography of Roman Italy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00393-4.

- Clarke, John R. (1991). The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 BC-AD 250. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07267-7.

- Laurence, Ray (2002). The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16616-0.

External links

- (in Italian) Geographical regions in Roman history: Italy