Vandal Kingdom

| Kingdom of the Vandals and Alans Regnum Vandalorum et Alanorum Vandaliric | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 435 AD–534 AD | |||||||||||||

.jpg) Coin depicting Gelimer (530–534)

| |||||||||||||

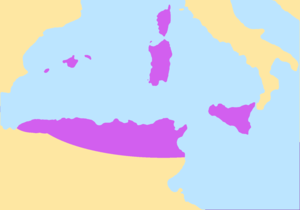

Greatest extent of the Vandal Kingdom c. 476 | |||||||||||||

| Capital |

Hippo Regius 435–439 [1] Carthage 439[2]–534[3] | ||||||||||||

| Common languages |

Latin (spoken by elite and clergy) Vulgar Latin and African Romance (spoken by common people) Vandalic (spoken among elite) Punic (spoken among common people) Numid (spoken among common people in rural areas) Medieval Greek (spoken among common people) | ||||||||||||

| Religion |

Arianism (among elite) Nicene Christianity then Chalcedonian Christianity | ||||||||||||

| Government | Pre-feudal Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

• 435–477 | Genseric | ||||||||||||

• 477–484 | Huneric | ||||||||||||

• 484-496 | Gunthamund | ||||||||||||

• 496-523 | Thrasamund | ||||||||||||

• 523-530 | Hilderic | ||||||||||||

• 530–534 | Gelimer | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| 435 AD | |||||||||||||

| 534 AD | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Tunisia | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Prehistoric |

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

The Vandal Kingdom (Latin: Regnum Vandalum) or Kingdom of the Vandals and Alans (Latin: Regnum Vandalorum et Alanorum) was established by the Germanic Vandal people under Genseric, and ruled in North Africa and the Mediterranean from 435 AD to 534 AD.

In 429, the Vandals, estimated to number 80,000 people, had crossed by boat from Spain to North Africa. They advanced eastward conquering the coastal regions of 21st century Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. In 435, the Roman Empire, then ruling in North Africa, allowed the Vandals to settle in the provinces of Numidia and Mauretania when it became clear that the Vandal army could not be defeated by Roman military forces. In 439 the Vandals renewed their advance eastward and captured Carthage, the most important city of North Africa. The fledgling kingdom then conquered the Roman-ruled islands of Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica in the Mediterranean Sea. In the 460s the Romans launched two unsuccessful military expeditions by sea in an attempt to overthrow the Vandals and reclaim North Africa. The conquest of North Africa by the Vandals was a blow to the beleaguered Western Roman Empire as North Africa was a major source of revenue and a supplier of grain (mostly wheat) to the city of Rome.

Although primarily remembered for the sack of Rome in 455 and their persecution of Nicene Christians in favor on their faith of Arian Christianity, the Vandals were also patrons of learning. Grand building projects continued, schools flourished and North Africa fostered many of the most innovative writers and natural scientists of the late Latin Western Roman Empire.[4]

The Vandal Kingdom ended in 534 when it was conquered by Belisarius in the Vandalic War and incorporated into the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire.

History

Establishment

The Vandals, under their new king Genseric (also known as Gaiseric or Geiseric), crossed to Africa in 429.[5] Although numbers are unknown and some historians debate the validity of estimates, based on Procopius' assertion that the Vandals and Alans numbered 80,000 when they moved to North Africa,[6] Peter Heather estimates that they could have fielded an army of around 15,000–20,000.[7] According to Procopius, the Vandals came to Africa at the request of Bonifacius, the military ruler of the region.[8] However, it has been suggested that the Vandals migrated to Africa in search of safety; they had been attacked by a Roman army in 422 and had failed to seal a treaty with them. Advancing eastwards along the African coast, the Vandals laid siege to the walled city of Hippo Regius in 430.[5] Inside, Saint Augustine and his priests prayed for relief from the invaders, knowing full well that the fall of the city would spell conversion or death for many Roman Christians. On 28 August 430, three months into the siege, St. Augustine (who was 75 years old) died[9] - perhaps from starvation or stress, as the wheat fields outside the city lay dormant and unharvested. After 14 months, hunger and diseases were ravaging both the city's inhabitants and the Vandals outside the city walls. The city eventually fell to the Vandals and they made it their first capital.[1]

Peace was made between the Romans and the Vandals in 435 through a treaty - between Valentinian III and Genseric - giving the Vandals control of coastal Numidia and parts of Mauretania. Genseric chose to break the treaty in 439 when he invaded the province of Africa Proconsularis and laid siege to Carthage.[10] The city was captured without a fight; the Vandals entered the city while most of the inhabitants were attending the races at the hippodrome. Genseric made it his capital, and styled himself the King of the Vandals and Alans, to denote the inclusion of his Alan allies into his realm. Conquering Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Malta and the Balearic Islands, he built his kingdom into a powerful state. Historian Cameron suggests that the new Vandal rule may not have been unwelcome to the population of North Africa as the previous landowners were generally unpopular.[11]

The impression given by sources such as Victor of Vita, Quodvultdeus, and Fulgentius of Ruspe was that the Vandal take-over of Carthage and North Africa led to widespread destruction. However, recent archaeological investigations have challenged this assertion. Although Carthage's Odeon was destroyed, the street pattern remained the same and some public buildings were renovated. The political centre of Carthage was the Byrsa Hill. New industrial centres emerged within towns during this period.[12] Historian Andy Merrills uses the large amounts of African red slip ware discovered across the Mediterranean dating from the Vandal period of North Africa to challenge the assumption that the Vandal rule of North Africa was a time of economic instability.[13] When the Vandals raided Sicily in 440, the Western Roman Empire was too preoccupied with war in Gaul to react. Theodosius II, emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, dispatched an expedition to deal with the Vandals in 441, however it only progressed as far as Sicily. The Western Empire under Valentinian III secured peace with the Vandals in 442.[14] Under the treaty the Vandals gained Byzacena, Tripolitania, part of Numidia, and confirmed their control of Proconsular Africa.[15]

The Grain Trade

Historians since Edward Gibbon have seen the capture of North Africa by the Vandals and Alans as the "deathblow"[16] and "the greatest single blow"[17] to the Western Roman Empire in its struggle to survive. Prior to the Vandals, northern Africa was prosperous and peaceful, requiring only a small percentage of the Roman Empire's military forces, and was an important source of taxes for the empire and grain for the city of Rome.[18] The scholar Josephus in the first century CE said that North Africa fed Rome for eight months of the year, with the other four months of needed grain coming from Egypt.[19]

The Roman need for grain from North Africa may have declined by the 5th century because of the diminishing population of the city of Rome and a decreasing number of Roman soldiers. Moreover, the treaty between Rome and the Vandals in 442 seems to have ensured that grain shipments would continue.[20] However, that treaty, in terms of halting hostilities between Rome and the Vandals, was honored more in the breach than in the observance and the Romans placed a high priority of recovering North Africa and regaining their control of grain from the Vandal Kingdom.[21]

Sack of Rome

The peace treaty of 442 did not halt Vandal raids in the western Mediterranean. During the next thirty-five years, with a large fleet, Genseric looted the coasts of the Eastern and Western Empires. After Attila the Hun's death in 453, however, the Romans turned their attention back to the Vandals, who were in control of some of the richest lands of their former empire.

In an effort to bring the Vandals into the fold of the Empire, Valentinian III offered his daughter's hand in marriage to Genseric's son. Before this treaty could be carried out, however, politics again played a crucial part in the blunders of Rome. Petronius Maximus, the usurper, killed Valentinian III in an effort to control the Empire. Diplomacy between the two factions broke down and in 455 with a letter from the Empress Licinia Eudoxia, begging Genseric's son to rescue her, the Vandals took Rome, along with the Empress Licinia Eudoxia and her daughters Eudocia and Placidia.

The chronicler Prosper of Aquitaine[22] offers the only fifth-century report that on 2 June 455, Pope Leo the Great received Genseric and implored him to abstain from murder and destruction by fire, and to be satisfied with pillage. The Vandals departed with countless valuables, including the spoils of the Temple in Jerusalem booty brought to Rome by Titus. Eudoxia and her daughter Eudocia were taken to North Africa.[15]

Later years

As a result of the Vandal sack of Rome, piracy in the Mediterranean, and the Roman need to recover control of the grain trade, the destruction of the Vandal kingdom became a priority for the Roman Empire. The Western Roman Emperor, Majorian, began to organize an offensive in the summer of 458; it was planned that a maritime force - staged from Cartagena in Spain - would take Mauretania and then march on Carthage whilst a simultaneous assault - commanded by Marcellinus - would retake Sicily. The Emperor assembled his fleet in 460 but his plan failed. Learning of the impending assault, Genseric 'put a scorched earth policy into effect in Mauretania - scouring the land and poisoning the wells in advance of the planned imperial offensive'; as well as this, Genseric led his own fleet against Majorian's force and defeated the Romans at Cartagena.[23][24]

In 468, both the Western and Eastern empires attempted to conquer Africa again with the 'most ambitious campaign ever launched against the Vandal state'; primary sources suggest that the fleet numbered 1,113 ships and carried 100,000 men but this figure has been rejected by modern historiography, with Peter Heather suggesting 30,000 troops and 50,000 soldiers and sailors combined, based on 16,000 Roman soldiers conveyed on 500 ships in 532. Andy Merrills and Richard Miles have asserted that the operation was undoubtedly extensive and 'deserves admiration for its logistical brilliance'.[25] At a naval battle in Cape Bon, Tunisia, the Vandals destroyed the Western fleet and part of the Eastern through the use of fire ships.[14] Following up the attack, the Vandals tried to invade the Peloponnese, but were driven back by the Maniots at Kenipolis with heavy losses.[26] In retaliation, the Vandals took 500 hostages at Zakynthos, hacked them to pieces and threw the pieces overboard on the way to Carthage.[26] In the 470s, the Romans abandoned their policy of war against the Vandals. The Western Germanic general Ricimer reached a treaty with the Vandals,[14] and in 476 Genseric was able to conclude a "perpetual peace" with Constantinople. Relations between the two states assumed a veneer of normality.[27] From 477 onwards, the Vandals produced their own coinage. It was restricted to bronze and silver low-denomination coins. Although the low-denomination imperial money was replaced, the high-denomination was not, demonstrating in the words of Merrills "reluctance to usurp the imperial prerogative".[28]

Genseric died on 25 January 477, 88 years of age. According to the law of succession which he had promulgated, the oldest male member of the royal house was to succeed. Thus he was succeeded by his son Huneric (477–484), who at first tolerated Nicene Christians, owing to his fear of Constantinople, but after 482 began to persecute Manichaeans and Nicene Christians.[29]

Gunthamund (484–496), his cousin and successor, sought internal peace with the Nicene Christians and ceased persecution once more. Externally, the Vandal power had been declining since Genseric's death, and Gunthamund lost large parts of Sicily to Theodoric's Ostrogoths and had to withstand increasing pressure from the native Berbers.

Gunthamund's successor Thrasamund (496–523), owing to his religious fanaticism, was hostile to Nicene Christians, but contented himself with bloodless persecutions.[29]

Conquest by the Eastern Roman Empire

Thrasamund's successor Hilderic (523–530) was the Vandal king most tolerant towards the trinitarian Christian Church. He granted it religious freedom; consequently Catholic synods were once more held in North Africa. However, he had little interest in war and left it to a family member, Hoamer. When Hoamer suffered a defeat against the Berbers, the Arian faction within the royal family led a revolt, and his cousin Gelimer (530–533) became king. Hilderic, Hoamer and their relatives were thrown into prison. Hilderic was deposed and murdered in 533.[30]

Byzantine Emperor Justinian I declared war, with the stated intention of restoring Hilderic to the Vandal throne. While an expedition was en route, a large part of the Vandal army and navy was led by Tzazo, Gelimer's brother, to Sardinia to deal with a rebellion by the Gothic nobleman Godas. As a result, the armies of the Byzantine Empire commanded by Belisarius were able to land unopposed 10 miles (16 km) from Carthage. Gelimer quickly assembled an army,[31] and met Belisarius at the Battle of Ad Decimum; the Vandals were winning the battle until Gelimer's brother Ammatas and nephew Gibamund fell in battle. Gelimer then lost heart and fled. Belisarius quickly took Carthage while the surviving Vandals fought on.[32]

On December 15, 533, Gelimer and Belisarius clashed again at the Battle of Tricamarum, some 20 miles (32 km) from Carthage. Again, the Vandals fought well but broke, this time when Gelimer's brother Tzazo fell in battle. Belisarius quickly advanced to Hippo, second city of the Vandal Kingdom, and in 534 Gelimer, besieged in Mount Pappua by the Herulian General Pharas, surrendered to the Byzantines, ending the Kingdom of the Vandals.

The Vandals' territory in North Africa (which is now northern Tunisia and eastern Algeria) became a Byzantine province, from which the Vandals were expelled. The best Vandal warriors were formed into five cavalry regiments, known as Vandali Iustiniani, and stationed on the Persian frontier. Some entered the private service of Belisarius.[33] Gelimer himself was honourably treated and received large estates in Galatia where he lived to be an old man. He was also offered the rank of patrician but had to refuse it because he was not willing to change his Arian faith.[29] In the words of historian Roger Collins: "The remaining Vandals were then shipped back to Constantinople to be absorbed into the imperial army. As a distinct ethnic unit they disappeared".[31]

Culture

Religion

From the beginning of their invasion of North Africa in 429, the Vandals – who were predominantly followers of Arianism – persecuted the Nicene church. This persecution began with the unfettered violence inflicted against the church during Genseric’s invasion but, with the legitimization of the Vandal kingdom, the oppression became entrenched in ‘more coherent religious policies’.[34] Victor of Vita’s History of the Vandal Persecution details the ‘wicked ferocity’ inflicted against church property and attacks against ‘many… distinguished bishops and noble priests’ in the first years of the conquest; similarly, Bishop Honoratus writes that ‘before our eyes men are murdered, women raped and we are ourselves collapse under torture’.[35][36] Using these and other corroborating sources, Andy Merrills has argued that there is ‘little doubt’ that the initial invasion was ‘brutally violent’.[37] Additionally, he has argued, along with Richard Miles that, the Vandals initially targeted the Nicene church for financial, rather than religious, reasons – seeking to rob the clergy of its wealth.[36]

However, once Genseric secured his hold over Numidia and Mauretania with the treaty of 435 he worked ‘to destroy the power of the Nicene Church in his new territories by seizing the basilicas of three of the most intransigent bishops and expelling them from their cities’.[38] Similar policies continued with the capture of Carthage in 439 as the Vandal king made efforts to simultaneously advance the Arian church whilst oppressing Nicene practices. Peter Heather highlights that four major churches within the city walls were confiscated for the Arians and a ban was imposed on all Nicene services in areas in which Vandals settled; Genseric also had Quodvultdeus (the city’s bishop) and many of his clergy exiled from Africa and refused ‘to allow replacements to be ordained… so that the total number of Nicene bishops within the Vandal kingdom suffered a decline’.[34] Laymen were excluded from office and frequently suffered confiscation of their property.[39] Diplomatic considerations took precedence over religious policy. In 454 Genseric installed Deogratius as the new bishop of Carthage (a position left empty since Quodvultdeus’ departure) at the request of Valentinian III; Heather argues that this accession was intended to improve relations as the Vandal king negotiated the marriage of his son, Huneric, to the Roman Emperor’s daughter, Eudocia.[40] However, with Valentinian's death and the worsening of relations with Rome and Constantinople Genseric persisted with oppressive religious policies, leaving the bishopric empty once again when Deogratius died in 457.

Peter Heather has argues that Genseric's promotion of the Arian church - with the accompanying persecution of the Nicene church - had political motivations. He notes a 'key distinction' between 'the anti-Nicene character 'of Genseric's actions in Proconsularis and the rest of his kingdom; persecution was most intense when it was in proximity to his Arian followers.[34] Heather suggests that Arianism was a means for Genseric to keep his followers united and under control, where there was interaction between his people and the Nicene church this strategy was threatened. Heather also notes that 'personal belief must have also played a substantial role in Genseric's decision making'.[34]

Huneric, Genseric’s son and successor, continued and intensified the repression of the Nicene church and attempts to make Arianism the primary religion in North Africa; indeed, much of Victor of Vita’s narrative focuses on the atrocities and persecutions committed during Huneric’s reign.[41] Priests were forbidden to practice the liturgy, homoousain books were destroyed, and almost 5000 bishops were forced to suffer exile in the desert.[42] Violence continued with ‘men and women… subjected to a series of torments including scalping, forced labour and execution by sword and fire.’[42] In 483, Huneric commanded all Catholic bishops in Africa, with a royal edict, to attend a debate with Arian representatives and in the aftermath of this conference Huneric forbid the Nicene clergy from assembling, carrying out baptisms or ordinations, and he ordered all Nicene churches and property to be closed.[42] Churches were then confiscated for the Royal Fisc or for Arian use.

Primary sources reveal little about Gunthamund's religious policies; yet, evidence does suggest that the new king was 'generally better disposed towards the Catholic faith than his predecessor [Huneric] had been' and maintained a period of tolerance.[43] Gunthamund ended the exile of a bishop called Eugenius and also restored the Nicene shrine of Agileus in Carthage.[43]

Thrasamund ended his late brother's policies of tolerance when he ascended to the throne, in 496. He reintroduced 'harsh measures against the Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy' but worked to maintain positive relations with the Romano-African lay elite' - his intention being to split the loyalties of the two groups.[43]

Generally most Vandal kings, except Hilderic, persecuted the Nicene Christians (as well as Donatists) to a greater or lesser extent, banning conversion for Vandals and exiling bishops.[44][45]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Andrew Merrills and Richard Miles, The Vandals (Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 60.

- ↑ An Empire of Cities, Penelope M. Allison, The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Roman World, ed. by Greg Woolf (Cambridge University Press, 2001), 223

- ↑ Andrew Merrills and Richard Miles, The Vandals, 3.

- ↑ Miles 2007, p. 1

- 1 2 Collins 2000, p. 124

- ↑ Procopius Wars 3.5.18–19 in Heather 2005, p. 512

- ↑ Heather 2005, pp. 197–198

- ↑ Procopius Wars 3.5.23–24 in Collins 2000, p. 124

- ↑ Newadvent.org

- ↑ Collins 2000, pp. 124–125

- ↑ Cameron 2000, pp. 553–554

- ↑ Merrills 2004, p. 10

- ↑ Merrills 2004, p. 11

- 1 2 3 Collins 2000, p. 125

- 1 2 Cameron 2000, p. 553

- ↑ Linn, Jason (Fall 2012), "The Roman Grain Supply, 441-455", Journal of Late Antiquity, Vol. 5, no. 2, p.298, and note 3, p. 298

- ↑ Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009), How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower, New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 358.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. 358

- ↑ Rickman, G.E. (1980), "The Grain Trade under the Roman Empire", Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol 36, The Seaborne Commerce of Ancient Rome, p. 264. Downloaded from JSTOR; Heather, pp. 275-276.

- ↑ Linn, pp. 298-299, 317-321

- ↑ Goldsworthy, pp.358-359

- ↑ Prosper's account of the event was followed by his continuator in the sixth century, Victor of Tunnuna, a great admirer of Leo quite willing to adjust a date or bend a point (Steven Muhlberger, "Prosper's Epitoma Chronicon: was there an edition of 443?" Classical Philology 81.3 (July 1986), pp 240-244).

- ↑ 1975-, Merrills, A. H. (Andrew H.), (2010). The Vandals. Miles, Richard, 1969-. Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 119–121. ISBN 9781405160681. OCLC 426065943.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, pp 358-359

- ↑ Heather 2005, p. 268.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 21

- ↑ Bury 1923, p. 125

- ↑ Merrills 2004, pp. 11–12

- 1 2 3 Catholic Encyclopedia 1913, "Vandals".

- ↑ Bury 1923, p. 131

- 1 2 Collins 2000, p. 126

- ↑ Bury 1923, pp. 133–135

- ↑ Bury 1923, pp. 139

- 1 2 3 4 Heather, Peter (2007). "Christianity and the Vandals in the Reign of Geiseric". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 50: 139–140 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ↑ Victor of Vita (1992). History of the Vandal Persecution. Translated by John Moorhead. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0 85323 127 3.

- 1 2 Merrills and Miles, p. 181.

- ↑ Merrills, Andy (2014). "Kingdoms of North Africa". In Michael Mass. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 266. ISBN 9781139128964.

- ↑ Merrills and Miles (2010), p.180.

- ↑ Collins 2000, pp. 125–126

- ↑ Heather (2010), p.141.

- ↑ Cameron 2000, p. 555

- 1 2 3 Merrills and Miles (2010), p. 185.

- 1 2 3 Merrills and Miles, p. 196.

- ↑ Swartz, Nico (2009). Historia Persecutionis. AFRICAN SUN MeDIA. p. 33. ISBN 192038300X. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ↑ Wace, Henry (1911). Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century A.D., with an Account of the Principal Sects and Heresies. p. 386. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

Sources

- Bury, John Bagnell (1923), History of the Later Roman Empire, from the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian (A.D.395 to A.D. 565), II, Macmillan

- Cameron, Averil (2000). "The Vandal conquest and Vandal rule (A.D. 429–534)". The Cambridge Ancient History. Late Antiquity: Empire and Successors, A.D. 425–600. XIV. Cambridge University Press. pp. 553–559.

- Collins, Roger (2000). "Vandal Africa, 429–533". The Cambridge Ancient History. Late Antiquity: Empire and Successors, A.D. 425–600. XIV. Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–126.

- Heather, Peter (2007), 'Christianity and the Vandals in the Reign of Geiseric', Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 50, pp. 137–146.

- Mass, Michael (ed.) (2014) The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781139128964

- Merrills, Andy (2004). "Vandals, Romans and Berbers: Understanding Late Antique North Africa". Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on Late Antique North Africa. Ashgate. pp. 3–28. ISBN 0-7546-4145-7.

- Merrills, Andrew; Miles, Richard (2010). The Vandals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 1405160683.

- Victor of Vita (1992) History of the Vandal Persecution trans. John Moorhead, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, ISBN 0853231273.