Italic peoples

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

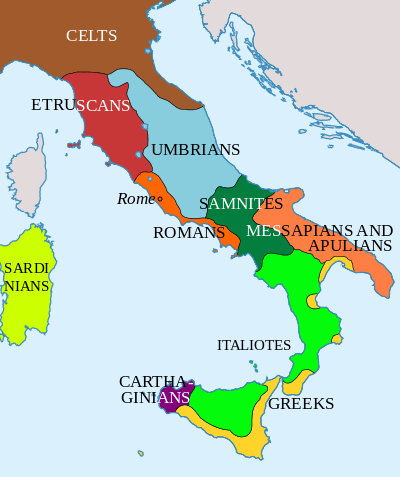

The Italic peoples are an Indo-European ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages and are, or were, related to italic descendants.

The Italic peoples are descended from Indo-Europeans who migrated into Italy from East-Central Europe in the 2nd-millenium BC. The Latins eventually achieved a dominant position among these tribes, establishing ancient Roman civilization. During this development, other Italic tribes adopted Latin language and culture in a process known as romanization. With the creation of the Roman Empire, romanization was spread to much of Europe. The modern Italic-speaking ethnic groups descended from this development speak Romance languages, and are collectively referred to as Romance peoples or Latin peoples. This includes the French people, Italians, Portuguese people, Romanians, Spaniards, Latinoamericans and others.

Classification

The Italics are an ethnolinguistic group who identified by their use of the Italic languages, which is one of the branches of Indo-European languages.

The term is sometimes used improperly, especially in nonspecialised literature, to refer to all pre-Roman people of Italy, including those not of Indo-European lineages, such as the Etruscans and the Raetians.[1]

History

Copper Age

During the Copper Age, at the same time as metalworking appeared, Indo-European people are believed to have migrated to Italy in several waves.[2] Associated with this migration are the Rinaldone culture and Remedello culture in Northern Italy, and the Gaudo culture of Southern Italy. These cultures were led by a warrior-aristocracy and are considered intrusive.[2] Their Indo-European character is suggested due to the presence of weapons in burials, the appearance of the horse in Italy at this time and material similarities with cultures of Central Europe.[2]

Early and Middle Bronze Age

%2C_The_Horse%2C_The_Wheel_and_Language.jpg)

According to David W. Anthony, between 3100–3000 BC, a massive migration of Indo-Europeans from the Yamna culture took place into the Danube Valley. Thousands of kurgans are attributed to this event. These migrations probably split off Pre-Italic, Pre-Celtic and Pre-Germanic from Proto-Indo-European.[3] By this time the Anatolian peoples and the Tocharians had already split of from other Indo-Europeans.[4] Hydronymy shows that Proto-Germanic homeland is in Central Germany, which would be very close to the homeland of Italic and Celtic languages as well.[5] The origin of a hypothetical ancestral "Italo-Celtic" people is to be found in today's eastern Hungary, settled around 3100 BC by the Yamna culture. This hypothesis is to some extent supported by the observation that Italic shares a large number of isoglosses and lexical terms with Celtic and Germanic, some of which are more likely to be attributed to the Bronze Age.[2] In particular, using Bayesian phylogenetic methods, Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson argued that proto-Italic speakers separated from proto-Germanic ones 5500 years before present, i.e. roughly the start of the Bronze Age.[6] This is further confirmed by the fact that Germanic language family shares more vocabulary with the Italic family than with the Celtic language family.[7]

From the late 3rd to the early 2nd millennium BC, tribes coming both from the north and from Franco-Iberia brought the Beaker culture[8] and the use of bronze smithing, to the Po Valley, to Tuscany and to the coasts of Sardinia and Sicily. The Beakers could have been the link which brought the Yamna dialects from Hungary to ]]Austria]] and Bavaria. These dialects might then have developed into Proto-Celtic.[9] The arrival of Indo-Europeans into Italy is in some sources ascribed to the Beakers.[1] A migration across the Alps from East-Central Europe by Italic tribes is though to have occurred around 1800 BC.[10][11]

In the mid-2nd millennium BC, the Terramare culture developed in the Po Valley.[12] The Terramare culture takes its name from the black earth (terra marna) residue of settlement mounds, which have long served the fertilizing needs of local farmers. These people were still hunters, but had domesticated animals; they were fairly skillful metallurgists, casting bronze in moulds of stone and clay, and they were also agriculturists, cultivating beans, the vine, wheat and flax. The Latino-Faliscan people have been associated with this culture, especially by the archaeologist Luigi Pigorini.[2]

Late Bronze Age

The Urnfield culture might have brought proto-Italic people from among the "Italo-Celtic" tribes who remained in Hungary into Italy.[9] These tribes are thought to have penetrated Italy from the east during the late 2nd millennium BC through the Proto-Villanovan culture.[9] They later crossed the Apennine Mountains and settled central Italy, including Latium. Before 1000 BC several Italic tribes had probably entered Italy. These divided into various groups and gradually came to occupy central Italy and southern Italy.[11] This period was characterized by widespread upheaval in the Mediterranean, including the emergence of the Sea Peoples and the Late Bronze Age collapse.[13]

The Proto-Villanovan culture dominated the peninsula and replaced the preceding Apennine culture. The Proto-Villanovans practiced cremation and buried the ashes of their dead in pottery urns of a distinctive double-cone shape. Generally speaking, Proto-Villanovan settlements have been found in almost the whole Italian peninsula from Veneto to eastern Sicily, although they were most numerous in the northern-central part of Italy. The most important settlements excavated are those of Frattesina in Veneto region, Bismantova in Emilia-Romagna and near the Monti della Tolfa, north of Rome. The Osco-Umbrians, the Veneti, and possibly the Latino-Faliscans too, have been associated with this culture.

In the 13th century BC, Proto-Celts (probably the ancestors of the Lepontii people), coming from the area of modern-day Switzerland, eastern France and south-western Germany (RSFO Urnfield group), entered Northern Italy (Lombardy and eastern Piedmont), starting the Canegrate culture, who not long time after, merging with the indigenous Ligurians, produced the mixed Golasecca culture.

Iron Age

In the early Iron Age, the relatively homogeneous Proto-Villanovan culture shows a process of fragmentation. In Tuscany and in part of Emilia-Romagna, Latium and Campania, the Proto-Villanovan culture was followed by the Villanovan culture. The Villanovan culture is closely associated with the Celtic Halstatt culture of Alpine Austria, and is characterised by the introduction of iron-working, the practice of cremation coupled with the burial of the ashes in distinctive pottery. The earliest remains of Villanovan culture date back to approx. 1100 BC.

In the region south of the Tiber (Latium Vetus), the Latial culture of the Latins emerges, while in the north-east of the peninsula the Este culture of the Veneti appeared. Roughly in the same period, from their core area in central Italy (modern-day Umbria and Sabina region), the Osco-Umbrians began to emigrate in various waves, through the process of Ver sacrum, the ritualized extension of colonies, in southern Latium, Molise and the whole southern half of the peninsula, replacing the previous tribes, such as the Opici and the Oenotrians. This corresponds with the emergence of the Terni culture, which had strong similarities with the Celtic cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène.[14] The Umbrian necropolis of Terni, which dates back to the 10th century BC, was identical under every aspect, to the Celtic necropolis of the Golasecca culture.[15]

Antiquity

By the mid-1th-millenium BC, the Latins of Rome were growing in power and influence. This led to the establishment of ancient Roman civilization. In order to combat the non-Italic Etruscans, several Italic tribes united in the Latin League. After the Latins had liberated themselves from Etruscan rule they acquired a dominant position among the Italic tribes. Frequent conflict between various Italic tribes followed. The best documented of these are the wars between the Latins and the Samnites.[1]

The Latins eventually succeeded in unifying the Italic elements in the country. Many non-Latin Italic tribes adopted Latin culture and acquired Roman citizenship. During this time Italic colonies were established throughout the country, and non-Italic elements eventually adoted Latin language and culture in a process known as romanization.[11] In the early 1th-century BC, several Italic tribes, in particular the Marsi and the Samnites, rebelled against Roman rule. This conflict is called the Social War. After Roman victory was secured, all peoples in Italy, except from the Celts of the Po Valley, were granted Roman citizenship.[1]

Rise of the Romance peoples

Aided by the rise of Christianity, romanization was eventually extended to the European areas dominated by Roman Empire. Roman methods of organization and technology also spread to the Germanic tribes living along Rome's European frontier. In the 5th-century AD these tribes migrated into the Western Roman Empire and amalgamated with the local Latin-speaking population.[1] The Germanic migration left a vacuum filled by the Slavs.[1]

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the use of the Latin language retreated in size, but was still widely used, such as through the Catholic Church as well as by others like the Germanic Visigoths and the Catholic Frankish kingdom of Clovis.[16]:1 In part due to regional dialects of the Latin language and local environments, several languages evolved from it, the Romance languages.[16]:4 The ethnic groups that emerged from this development are collectively referred to as Romance peoples or Latin peoples, while still belonging to the Italic people group.[1][17] The Spanish and Portuguese languages prominently spread into North, Central, and South America through colonization.[16]:8,10 The French language has spread to most inhabited continents through colonialism, however the ethnic qualification of the Italic ethnolinguistic group is only found in France, and some parts of Haiti. [16]:13–15 The Italian language developed as a national language of Italy beginning in the 19th century out of several similar Romance dialects.[16]:312 The Romanian language has developed primarily in the Daco-Romanian variant that is the national language of Romania, but also other Romanian variants such as Aromanian is spoken in Bulgaria, Greece, Albania, Montenegro, Serbia and Macedonia by Aromanian minority. Today, Italic peoples can be found all throughout Latin America and Romance-speaking Europe.

Romance ethnic groups include:[17]

- Andorrans[18]

- Argentines

- Aromanians

- Asturians

- Brazilians

- Bolivians

- Canarians

- Catalans[19]

- Chileans

- Colombians

- Costa Ricans

- Corsicans[20]

- Cubans

- Dominicans

- Ecuadorians

- French people[21]

- Galicians

- Guatemalans

- Haitians

- Hondurans

- Italians (including Vaticans and Sammarinese)[22]

- Leonese

- Ligurians

- Mexicans

- Monacans

- Nicaraguans

- Normans

- Occitans

- Panamanians

- Paraguayans

- Peruvians

- Piedmontese

- Portuguese

- Romands[23]

- Romanians

- Romansh people

- Sards[24]

- Salvadorans

- Savoyards

- Sicilians

- Spaniards

- Uruguayans

- Venezuelans

- Walloons

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 452-459

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mallory 1997, p. 314-319

- ↑ Anthony 2007, p. 305

- ↑ Anthony 2007, p. 344

- ↑ Hans, Wagner. "Anatolien war nicht Ur-Heimat der indogermanischen Stämme". eurasischesmagazin. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ↑ "Language evolution and human history: what a difference a date makes, Russell D. Gray, Quentin D. Atkinson and Simon J. Greenhill (2011)".

- ↑ "A Grammar of Proto-Germanic, Winfred P. Lehmann Jonathan Slocum" (PDF).

- ↑ p144, Richard Bradley The prehistory of Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-521-84811-3

- 1 2 3 Anthony 2007, p. 367

- ↑ "Italic languages: Origins of the Italic languages". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "History of Europe: Romans". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ↑ Pearce, Mark (December 1, 1998). "New research on the terramare of northern Italy". Antiquity.

- ↑ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 620-658

- ↑ Leonelli, Valentina. La necropoli delle Acciaierie di Terni: contributi per una edizione critica (Cestres ed.). p. 33.

- ↑ Farinacci, Manlio. Carsulae svelata e Terni sotterranea. Associazione Culturale UMRU - Terni.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harris, Martin; Vincent, Nigel (2001). Romance Languages. London, England, UK: Routledge.

- 1 2 Minahan 2000, p. 776

- ↑ Minahan 2000, p. 47

- ↑ Minahan 2000, p. 156

- ↑ Minahan 2000, p. 182

- ↑ Minahan 2000, p. 257

- ↑ Minahan 2000, p. 343

- ↑ Minahan 2000, p. 545

- ↑ Minahan 2000, p. 588

Bibliography

- Anthony, David (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- Devoto, Giacomo; Buti, Gianna G. (1974). Preistoria e storia delle regioni d'Italia. Florence: Sansoni.

- Devoto, Giacomo (1951). Gli antichi Italici. Florence: Vallechi.

- Mallory, J. P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Douglas Q. Adams. ISBN 1884964982. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313309841.

- Moscati, Sabatino (1998). Così nacque l'Italia: profili di popoli riscoperti. Turin: Società Editrice Internazionale.

- Pigorini, Luigi (1910). Gli abitanti primitivi dell'Italia. Rome: Bertero.

- Villar, Francisco (1997). Gli Indoeuropei e le origini dell'Europa. Bologna: Il Mulino. ISBN 88-15-05708-0.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181.

no |location=Bologna |isbn=88-15-05708-0}}

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181.