Late Bronze Age collapse

| Bronze Age |

| ↑ Chalcolithic |

|

Near East (c. 3300–1200 BC) South Asia (c. 3300–1200 BC) Europe (c. 3200–600 BC)

East Asia (c. 2000–300 BC) |

| ↓Iron Age |

|

| Human history | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ Prehistory | |||

| Recorded history | |||

| Ancient | |||

| Postclassical | |||

| Modern | |||

|

|||

| ↓ Future | |||

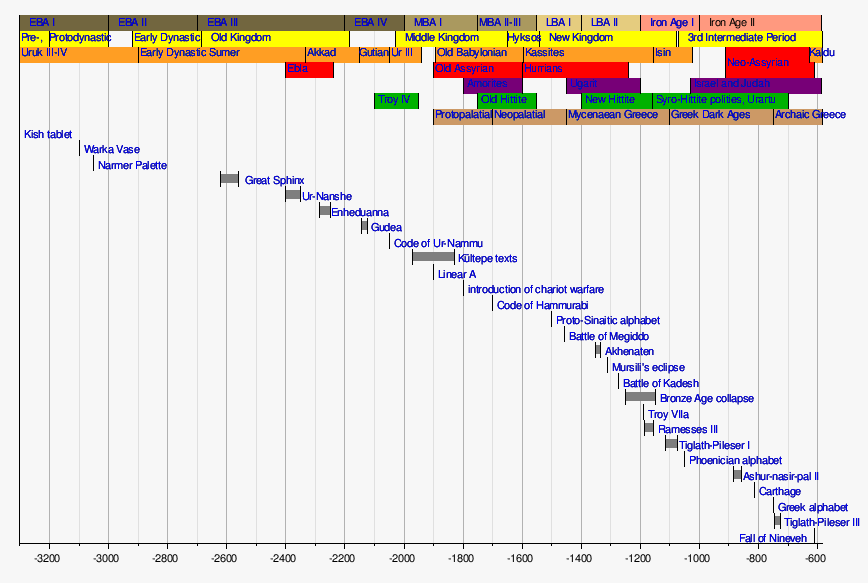

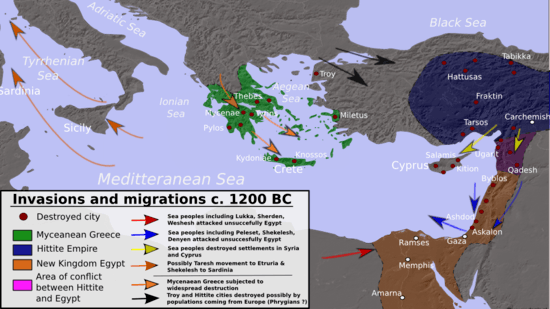

The Late Bronze Age collapse involved a dark-age transition period in the Near East, Asia Minor, Aegean region, North Africa, Caucasus, Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age, a transition which historians believe was violent, sudden, and culturally disruptive. The palace economy of the Aegean region and Anatolia that characterised the Late Bronze Age disintegrated, transforming into the small isolated village cultures of the Greek Dark Ages. The half-century between c. 1200 and 1150 BC saw the cultural collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms, of the Kassite dynasty of Babylonia, of the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and the Levant, and of the Egyptian Empire;[1] the destruction of Ugarit and the Amorite states in the Levant, the fragmentation of the Luwian states of western Asia Minor, and a period of chaos in Canaan.[2] The deterioration of these governments interrupted trade routes and severely reduced literacy in much of the known world.[3] In the first phase of this period, almost every city between Pylos and Gaza was violently destroyed, and many abandoned, including Hattusa, Mycenae, and Ugarit.[4] According to Robert Drews:

Within a period of forty to fifty years at the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the twelfth century almost every significant city in the eastern Mediterranean world was destroyed, many of them never to be occupied again.[5]

A very few powerful states, particularly Assyria and Elam, survived the Bronze Age collapse – but by the end of the 12th century BC, Elam waned after its defeat by Nebuchadnezzar I, who briefly revived Babylonian fortunes before suffering a series of defeats by the Assyrians. Upon the death of Ashur-bel-kala in 1056 BC, Assyria went into a comparative decline for the next 100 or so years, its empire shrinking significantly. By 1020 BC Assyria appears to have controlled only the areas in its immediate vicinity; the well-defended Assyria itself was not threatened during the collapse. Gradually, by the end of the ensuing Dark Age, remnants of the Hittites coalesced into small Neo-Hittite and Syro-Hittite states in Cilicia and the Levant, the latter states being composed of mixed Hittite and Aramean polities. Beginning in the mid-10th century BC, a series of small Aramaean kingdoms formed in the Levant and the Philistines settled in southern Canaan where the Canaanite-speaking Semites had coalesced into a number of defined polities such as Israel, Moab, Edom and Ammon. From 935 BC Assyria began to reorganise and once more expand outwards, leading to the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-605 BC), which came to control a vast area from the Caucasus to Egypt, and from Greek Cyprus to Persia. Phrygians, Cimmerians and Lydians arrived in Asia Minor, and a new Hurrian polity of Urartu formed in eastern Asia Minor and the southern Caucasus, where the Colchians (Georgians) also emerged. Iranian peoples such as the Persians, Medes, Parthians and Sargatians first appeared in Ancient Iran soon after 1000 BC, displacing earlier non-Indo-European Kassites, Hurrians and Gutians in the northwest of the region, although the indigenous language isolate-speaking Elamites and Manneans continued to dominate the southwest and Caspian Sea regions respectively. After the Orientalising period in the Aegean, Classical Greece emerged.

Regional evidence

Evidence of destruction

Anatolia

Before the Bronze Age collapse, Anatolia (Asia Minor) was dominated by a number of peoples of varying ethno-linguistic origins: including Semitic Assyrians and Amorites, language isolate-speaking Hurrians, Kaskians and Hattians, and later-arriving Indo-European peoples such as Luwians, Hittites, Mitanni, and Mycenaean Greeks. From the 16th century BC, the Mitanni (a migratory minority speaking an Indo-Aryan language) formed a ruling class over the Hurrians, an ancient indigenous Caucasian people who spoke a Hurro-Urartian language, a language isolate. Similarly, the Indo-Anatolian-speaking Hittites absorbed the Hattians,[6] a people speaking a language that may have been of the non–Indo-European North Caucasian language group or a language isolate.

Every Anatolian site, apart from integral Assyrian regions in the south east, and regions in eastern, central and southern Anatolia under the control of the powerful Middle Assyrian Empire (1392–1050 BC) that was important during the preceding Late Bronze Age shows a destruction layer, and it appears that in these regions civilization did not recover to the level of the Assyrians and Hittites for another thousand years or so. The Hittites, already weakened by a series of military defeats and annexations of their territory by the Middle Assyrian Empire (which had already destroyed the Hurrian-Mitanni Empire) then suffered a coup de grâce when Hattusas, the Hittite capital, was burned, probably by the language isolate-speaking Kaskians, long indigenous to the southern shores of the Black Sea, and possibly aided by the incoming Indo-European–speaking Phrygians). The city was abandoned and never reoccupied.

Karaoğlan[lower-alpha 1] (near present-day Ankara) was burned and the corpses left unburied.[8] Many other sites that were not destroyed were abandoned.[9] The Luwian city of Troy was destroyed at least twice, before being abandoned until Roman times. (Trojan War)

The Phrygians had arrived (probably over the Bosphorus or Caucasus) in the 13th century BC[10], before being first checked by the Assyrians and then conquered by them in the Early Iron Age of the 12th century BC. Other groups of Indo-European peoples followed the Phrygians into the region, most prominently the Doric Greeks and Lydians, and in the centuries after the period of Bronze Age Collapse, the Cimmerians, and Scythians also appeared. The Semitic Arameans, Kartvelian-speaking Colchians (Georgians), and revived Hurrian polities, particularly Urartu, Nairi and Shupria also emerged in parts of the region and southern Caucasus. The Assyrians simply continued their already extant policies, by conquering any of these new peoples and polities they came into contact with, as they had with the preceding polities of the region. However Assyria gradually withdrew from much of the region for a time in the second half of the 11th century BC, although they continued to campaign militarily at times, in order to protect their borders and keep trade routes open, until a renewed vigorous period of expansion in the late 10th century BC.

These sites in Anatolia show evidence of the collapse:

Cyprus

The catastrophe separates Late Cypriot II (LCII) from the LCIII period, with the sacking and burning of Enkomi, Kition, and Sinda, which may have occurred twice before those sites were abandoned.[12] During the reign of the Hittite king Tudhaliya IV (reigned c. 1237–1209 BC), the island was briefly invaded by the Hittites,[13] either to secure the copper resource or as a way of preventing piracy.

Shortly afterwards, the island was reconquered by his son around 1200 BC. Some towns (Enkomi, Kition, Palaeokastro and Sinda) show traces of destruction at the end of LCII. Whether or not this is really an indication of a Mycenean invasion is contested. Originally, two waves of destruction in c. 1230 BC by the Sea Peoples and c. 1190 BC by Aegean refugees have been proposed.[14]

Alashiya was plundered by the Sea Peoples and ceased to exist in 1085.

The smaller settlements of Ayios Dhimitrios and Kokkinokremnos, as well as a number of other sites, were abandoned but do not show traces of destruction. Kokkinokremos was a short-lived settlement, where various caches concealed by smiths have been found. That no one ever returned to reclaim the treasures suggests that they were killed or enslaved. Recovery occurred only in the Early Iron Age with Phoenician and Greek settlement.

These sites in Cyprus show evidence of the collapse:

Syria

Ancient Syria had been initially dominated by a number of indigenous Semitic-speaking peoples. The East Semitic-speaking Eblaites, Akkadians and Assyrians and the Northwest Semitic-speaking Ugarites and Amorites prominent among them.[15] Syria during this time was known as "The land of the Amurru".

Before and during the Bronze Age Collapse, Syria became a battle ground between the empires of the Hittites, Assyrians, Mitanni and Egyptians between the 15th and late 13th centuries BC, with the Assyrians destroying the Hurri-Mitanni empire and annexing much of the Hittite empire. The Egyptian empire had withdrawn from the region after failing to overcome the Hittites and being fearful of the ever growing Assyrian might, leaving much of the region under Assyrian control until the late 11th century BC. Later the coastal regions came under attack from the Sea Peoples. During this period, from the 12th century BC, the incoming Northwest Semitic-speaking Arameans came to demographic prominence in Syria, the region outside of the Canaanite-speaking Phoenician coastal areas eventually came to speak Aramaic and the region came to be known as Aramea and Eber Nari. The Babylonians belatedly attempted to gain a foothold in the region during their brief revival under Nebuchadnezzar I in the 12th century BC, however they too were overcome by their Assyrian neighbours. The modern term 'Syria' is a later Indo-European corruption of 'Assyria' which only became formally applied to the Levant during the Seleucid Empire (323–150 BC) (see Etymology of Syria).

Levantine sites previously showed evidence of trade links with Mesopotamia (Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia), Anatolia (Hattia, Hurria, Luwia and later the Hittites), Egypt and the Aegean in the Late Bronze Age. Evidence at Ugarit shows that the destruction there occurred after the reign of Merneptah (ruled 1213–1203 BC) and even the fall of Chancellor Bay (died 1192 BC). The last Bronze Age king of the Semitic state of Ugarit, Ammurapi, was a contemporary of the Hittite king Suppiluliuma II. The exact dates of his reign are unknown.

A letter by the king is preserved on one of the clay tablets found baked in the conflagration of the destruction of the city. Ammurapi stresses the seriousness of the crisis faced by many Levantine states from invasion by the advancing Sea Peoples in a dramatic response to a plea for assistance from the king of Alasiya. Ammurapi highlights the desperate situation Ugarit faced in letter RS 18.147:

My father, behold, the enemy's ships came (here); my cities(?) were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots(?) are in the Land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the Land of Lukka?... Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.[16]

No help arrived and Ugarit was burned to the ground at the end of the Bronze Age. Its destruction levels contained Late Helladic IIIB ware, but no LH IIIC (see Mycenaean period). Therefore, the date of the destruction is important for the dating of the LH IIIC phase. Since an Egyptian sword bearing the name of Pharaoh Merneptah was found in the destruction levels, 1190 BC was taken as the date for the beginning of the LH IIIC.

A cuneiform tablet found in 1986 shows that Ugarit was destroyed after the death of Merneptah. It is generally agreed that Ugarit had already been destroyed by the 8th year of Ramesses III, 1178 BC. These letters on clay tablets found baked in the conflagration of the destruction of the city speak of attack from the sea, and a letter from Alashiya (Cyprus) speaks of cities already being destroyed by attackers who came by sea. It also speaks of the Ugarit fleet being absent, patrolling the Lycian coast.

The West Semitic Arameans eventually superseded the earlier Semitic Amorites, Canaanites and people of Ugarit. The Arameans, together with the Phoenician Canaanites and Neo-Hittites came to dominate most of the region demographically, however these people, and the Levant in general, were also conquered and dominated politically and militarily by the Middle Assyrian Empire until Assyria's withdrawal in the late 11th century BC, although the Assyrians continued to conduct military campaigns in the region. However with the rise of Neo Assyrian Empire in the late 10th century BC, the entire region once again fell to Assyria.

These sites in Syria show evidence of the collapse:

Southern Levant

Egyptian evidence shows that from the reign of Horemheb (ruled either 1319 or 1306 to 1292 BC), wandering Shasu were more problematic than the earlier Apiru. Ramesses II (ruled 1279–1213 BC) campaigned against them, pursuing them as far as Moab, where he established a fortress, after a near defeat at the Battle of Kadesh. During the reign of Merneptah, the Shasu threatened the "Way of Horus" north from Gaza. Evidence shows that Deir Alla (Succoth) was destroyed after the reign of Queen Twosret (ruled 1191–1189 BC).[17]

The destroyed site of Lachish was briefly reoccupied by squatters and an Egyptian garrison, during the reign of Ramesses III (ruled 1186–1155 BC). All centres along a coastal route from Gaza northward were destroyed, and evidence shows Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Akko, and Jaffa were burned and not reoccupied for up to thirty years. Inland Hazor, Bethel, Beit Shemesh, Eglon, Debir, and other sites were destroyed. Refugees escaping the collapse of coastal centres may have fused with incoming nomadic and Anatolian elements to begin the growth of terraced hillside hamlets in the highlands region that was associated with the later development of the Hebrews.[17]

During the reign of Rameses III, Philistines were allowed to resettle the coastal strip from Gaza to Joppa, Denyen (possibly the tribe of Dan in the Bible, or more likely the people of Adana, also known as Danuna, part of the Hittite Empire) settled from Joppa to Acre, and Tjekker in Acre. The sites quickly achieved independence, as the Tale of Wenamun shows.

These sites in Southern Levant show evidence of the collapse:

Greece

None of the Mycenaean palaces of the Late Bronze Age survived (with the possible exception of the Cyclopean fortifications on the Acropolis of Athens), with destruction being heaviest at palaces and fortified sites. Up to 90% of small sites in the Peloponnese were abandoned, suggesting a major depopulation.

The Bronze Age collapse marked the start of what has been called the Greek Dark Ages, which lasted roughly 400 years and ended with the establishment of Archaic Greece. Other cities like Athens continued to be occupied, but with a more local sphere of influence, limited evidence of trade and an impoverished culture, from which it took centuries to recover.

These sites in Greece show evidence of the collapse:

Areas that survived

Mesopotamia

The Middle Assyrian Empire (1392–1056 BC) had destroyed the Hurrian-Mitanni Empire, annexed much of the Hittite Empire and eclipsed the Egyptian Empire, and at the beginning of the Late Bronze Age collapse controlled an empire stretching from the Caucasus mountains in the north to the Arabian peninsula in the south, and from Ancient Iran in the east to Cyprus in the west. However, in the 12th century BC, Assyrian satrapies in Anatolia came under attack from the Mushki (Phrygians), and those in the Levant from Arameans, but Tiglath-Pileser I (reigned 1114–1076 BC) was able to defeat and repel these attacks, conquering the incomers. The Middle Assyrian Empire survived intact throughout much of this period, with Assyria dominating and often ruling Babylonia directly, controlling south east and south western Anatolia, north western Iran and much of northern and central Syria and Canaan, as far as the Mediterranean and Cyprus.[19]

The Arameans and Phrygians were subjected, and Assyria and its colonies were not threatened by the Sea Peoples who had ravaged Egypt and much of the East Mediterranean, and the Assyrians often conquered as far as Phoenicia and the East Mediterranean. However, after the death of Ashur-bel-kala in 1056 BC, Assyria withdrew to areas close to its natural borders, encompassing what is today northern Iraq, north east Syria, the fringes of north west Iran, and south eastern Turkey. Assyria still retained a stable monarchy, the best army in the world, and an efficient civil administration, enabling it to survive the Bronze Age Collapse intact. Assyrian written records remained numerous and the most consistent in the world during the period, and the Assyrians were still able to mount long range military campaigns in all directions when necessary. From the late 10th century BC, it once more began to assert itself internationally, with the Neo-Assyrian Empire growing to be the largest the world had yet seen.[19]

The situation in Babylonia was very different. After the Assyrian withdrawal, it was still subject to periodic Assyrian (and Elamite) subjugation, and new groups of Semites, such as the Aramaeans, Suteans (and in the period after the Bronze Age Collapse, Chaldeans also), spread unchecked into Babylonia from the Levant, and the power of its weak kings barely extended beyond the city limits of Babylon. Babylon was sacked by the Elamites under Shutruk-Nahhunte (c. 1185–1155 BC), and lost control of the Diyala River valley to Assyria.

Egypt

After apparently surviving for a while, the Egyptian Empire collapsed in the mid-twelfth century BC (during the reign of Ramesses VI, 1145 to 1137 BC). Previously, the Merneptah Stele (c. 1200 BC) spoke of attacks (Libyan War) from Putrians (from modern Libya), with associated people of Ekwesh, Shekelesh, Lukka, Shardana and Tursha or Teresh (possibly Troas), and a Canaanite revolt, in the cities of Ashkelon, Yenoam and among the people of Israel. A second attack (Battle of the Delta and Battle of Djahy) during the reign of Ramesses III (1186–1155 BC) involved Peleset, Tjeker, Shardana and Denyen.

Conclusion

Robert Drews describes the collapse as "the worst disaster in ancient history, even more calamitous than the collapse of the Western Roman Empire."[20] Cultural memories of the disaster told of a "lost golden age": for example, Hesiod spoke of Ages of Gold, Silver, and Bronze, separated from the cruel modern Age of Iron by the Age of Heroes. Rodney Castledon suggests that memories of the Bronze Age collapse influenced Plato's story of Atlantis[21] in Timaeus and the Critias.

Possible causes

Various theories have been put forward as possible contributors to the collapse, many of them mutually compatible.

Environmental

Climate change

Changes in climate similar to the Younger Dryas period or the Little Ice Age punctuate human history. The local effects of these changes may cause crop failures in multiple consecutive years, leading to warfare as a last-ditch effort at survival. The triggers for climate change are still debated, but ancient peoples could not have predicted substantial climate changes.

Volcanoes

The Hekla 3 eruption approximately coincides with this period; and, while the exact date is under considerable dispute, one group calculated the date to be specifically 1159 BC, implicating the eruption in the collapse in Egypt.[22]

Drought

Using the Palmer Drought Index for 35 Greek, Turkish and Middle Eastern weather stations, it was shown that a drought of the kind that persisted from January AD 1972 would have affected all of the sites associated with the Late Bronze Age collapse.[23] Drought could have easily precipitated or hastened socioeconomic problems and led to wars.

More recently, it has been shown how the diversion of midwinter storms from the Atlantic to north of the Pyrenees and the Alps, bringing wetter conditions to Central Europe but drought to the Eastern Mediterranean, was associated with the Late Bronze Age collapse.[24]

Pollen in sediment cores from the Dead Sea and the Sea of Galilee show that there was a period of severe drought at the start of the collapse.[25][26]

Cultural

Ironworking

The Bronze Age collapse may be seen in the context of a technological history that saw the slow, comparatively continuous spread of ironworking technology in the region, beginning with precocious iron-working in the present Bulgaria and Romania in the 13th and 12th centuries BC.[27]

Leonard R. Palmer suggested that iron, superior to bronze for weapons manufacture, was in more plentiful supply and so allowed larger armies of iron users to overwhelm the smaller bronze-equipped armies of maryannu chariotry.[28]

Changes in warfare

Robert Drews argues[29] for the appearance of massed infantry, using newly developed weapons and armor, such as cast rather than forged spearheads and long swords, a revolutionising cut-and-thrust weapon,[30] and javelins. The appearance of bronze foundries suggests "that mass production of bronze artifacts was suddenly important in the Aegean". For example, Homer uses "spears" as a virtual synonym for "warriors".

Such new weaponry, in the hands of large numbers of "running skirmishers", who could swarm and cut down a chariot army, would destabilize states that were based upon the use of chariots by the ruling class. That would precipitate an abrupt social collapse as raiders began to conquer, loot and burn cities.[31][32][33]

General systems collapse

A general systems collapse has been put forward as an explanation for the reversals in culture that occurred between the Urnfield culture of the 12th and 13th centuries BC and the rise of the Celtic Hallstatt culture in the 9th and 10th centuries BC.[34] General systems collapse theory, pioneered by Joseph Tainter,[35] hypothesises how social declines in response to complexity may lead to a collapse resulting in simpler forms of society.

In the specific context of the Middle East, a variety of factors – including population growth, soil degradation, drought, cast bronze weapon and iron production technologies – could have combined to push the relative price of weaponry (compared to arable land) to a level unsustainable for traditional warrior aristocracies. In complex societies that were increasingly fragile and less resilient, the combination of factors may have contributed to the collapse.

The growing complexity and specialization of the Late Bronze Age political, economic, and social organization in Carol Thomas and Craig Conant's phrase[36] together made the organization of civilization too intricate to reestablish piecewise when disrupted. That could explain why the collapse was so widespread and able to render the Bronze Age civilizations incapable of recovery. The critical flaws of the Late Bronze Age are its centralisation, specialisation, complexity, and top-heavy political structure. These flaws then were exposed by sociopolitical events (revolt of peasantry and defection of mercenaries), fragility of all kingdoms (Mycenaean, Hittite, Ugaritic, and Egyptian), demographic crises (overpopulation), and wars between states. Other factors that could have placed increasing pressure on the fragile kingdoms include piracy by the Sea Peoples interrupting maritime trade, as well as drought, crop failure, famine, or the Dorian migration or invasion.[37]

See also

- Greek Dark Ages—period following the Bronze Age collapse

- Third Intermediate Period of Egypt—a similar period in Egypt

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed by Eric H. Cline

- Iron Age Cold Epoch

Notes

References

- ↑ For Syria, see M. Liverani, "The collapse of the Near Eastern regional system at the end of the Bronze Age: the case of Syria" in Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World, M. Rowlands, M.T. Larsen, K. Kristiansen, eds. (Cambridge University Press) 1987.

- ↑ S. Richard, "Archaeological sources for the history of Palestine: The Early Bronze Age: The rise and collapse of urbanism", The Biblical Archaeologist (1987)

- ↑ Russ Crawford (2006). "Chronology". In Stanton, Andrea; Ramsay, Edward; Seybolt, Peter J; Elliott, Carolyn. Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. Sage. p. xxix. ISBN 978-1412981767.

- ↑ The physical destruction of palaces and cities is the subject of Robert Drews's The End of the Bronze Age: changes in warfare and the catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C., 1993.

- ↑ Drews, 1993, p. 4

- ↑ Gurnet, Otto, (1982), The Hittites (Penguin) pp. 119–130.

- ↑ Robbins, p. 170

- ↑ Robert Drews (1995). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0691025916.

- ↑ Manuel Robbins (2001). Collapse of the Bronze Age: The Story of Greece, Troy, Israel, Egypt, and the Peoples of the Sea. iUniverse. p. 170. ISBN 978-0595136643.

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor. The Kingdom of the Hittites. (Clarendon), p. 379

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor. The Kingdom of the Hittites (Clarendon), p. 374.

- ↑ Robbins, Manuel (2001). Collapse of the Bronze Age: The Story of Greece, Troy, Israel and Egypt and the Peoples of the Sea. pp. 220–239

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor. The Kingdom of the Hittites (Clarendon), p. 366.

- ↑ Paul Aström has proposed dates of 1190 and 1179 BC (Aström).

- ↑ Woodard, Roger D. (2008). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1139469340.

- ↑ Jean Nougaryol et al. (1968) Ugaritica V: 87–90 no. 24

- 1 2 Tubbs, Johnathan (1998), "Canaanites" (British Museum Press)

- ↑ Drews, Robert (1993), The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 BC (Princeton Uni Press)

- 1 2 Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq

- ↑ Drews 1993:1, quotes Fernand Braudel's assessment that the Eastern Mediterranean cultures returned almost to a starting-point ("plan zéro"), "L'Aube", in Braudel, F. (ed.) (1977), La Mediterranee: l'espace et l'histoire (Paris)

- ↑ Castledon, Rodney (1998), "Atlantis Destroyed" (Routledge)

- ↑ Yurco, Frank J. "End of the Late Bronze Age and Other Crisis Periods: A Volcanic Cause". in Teeter, Emily; Larson, John (eds.). Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente. (Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 58.) Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. 1999:456–458. ISBN 1885923090.

- ↑ Weiss, Harvey (June 1982). "The decline of Late Bronze Age civilization as a possible response to climatic change". Climatic Change. 4 (2): 173–198. doi:10.1007/BF00140587.

- ↑ Fagan, Brian M. (2003). The Long Summer: How Climate Changed Civilization. Basic Books.

- ↑ Kershner, Isabel (22 October 2013). "Pollen Study Points to Drought as Culprit in Bronze Age Mystery". The New York Times. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0431.

- ↑ Langgut, Dafna; Finkelstein, Israel ; Litt, Thomas (October 2013) "Climate and the late Bronze Collapse: New evidence from the southern Levant", Journal of Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, 40 (2): 149–175.

- ↑ See A. Stoia and the other essays in M.L. Stig Sørensen and R. Thomas, eds., The Bronze Age: Iron Age Transition in Europe (Oxford) 1989, and T.H. Wertime and J.D. Muhly, The Coming of the Age of Iron (New Haven) 1980.

- ↑ Palmer, Leonard R (1962). Mycenaeans and Minoans: Aegean Prehistory in the Light of the Linear B Tablets. New York, Alfred A. Knopf

- ↑ Drews 1993:192ff

- ↑ Drews 1993:194

- ↑ Drews, R. (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. (Princeton).

- ↑ McGoodwin, Michael. "Drews (Robert) End of Bronze Age Summary". mcgoodwin.net.

- ↑ "alan little's weblog". alanlittle.org.

- ↑ http://www.iol.ie/~edmo/linktoprehistory.html History of Castlemagner, on the web page of the local historical society.

- ↑ Tainter, Joseph (1976). The Collapse of Complex Societies (Cambridge University Press).

- ↑ Thomas, Carol G.; Conant, Craig. (1999) Citadel to City-state: The Transformation of Greece, 1200–700 B.C.E.,

- ↑ Cline, Eric H. (2014). "1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed". Princeton University Press.

Further reading

- Dickinson, Oliver (2007). The Aegean from Bronze Age to Iron Age: Continuity and Change Between the Twelfth and Eighth Centuries BC. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415135900.

- Cline, Eric H. (2014). 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691140896.

External links

- Ancient History at Curlie (based on DMOZ)