Joshua Tree National Park

| Joshua Tree National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

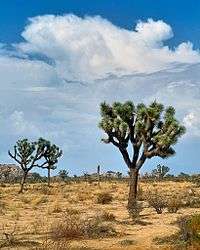

Cyclops and Pee Wee Formations near Hidden Valley Campground at dawn | |

Location in the United States  Location in California | |

| Location | Riverside County and San Bernardino County, California, United States |

| Nearest city | Yucca Valley, San Bernardino |

| Coordinates | 33°47′N 115°54′W / 33.79°N 115.90°WCoordinates: 33°47′N 115°54′W / 33.79°N 115.90°W |

| Area | 790,636 acres (319,959 ha)[1] |

| Established | October 31, 1994 |

| Visitors | 2,853,619 (in 2017)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website |

Official website |

Joshua Tree National Park is an American national park in southeastern California, east of Los Angeles, near San Bernardino and Palm Springs. The park is named for the Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia) native to the Mojave Desert. Originally declared a national monument in 1936, Joshua Tree was redesignated as a national park in 1994 when the U.S. Congress passed the California Desert Protection Act.[3] Encompassing a total of 790,636 acres (1,235.37 sq mi; 3,199.59 km2)[1]—an area slightly larger than the state of Rhode Island—the park includes 429,690 acres (671.39 sq mi; 1,738.89 km2) of designated wilderness. Straddling the border between San Bernardino County and Riverside County, the park includes parts of two deserts, each an ecosystem whose characteristics are determined primarily by elevation: the higher Mojave Desert and the lower Colorado Desert. The Little San Bernardino Mountains traverse the southwest edge of the park.[4]

History

Early

The earliest known residents of the land in and around what later became Joshua Tree National Park were the people of the Pinto Culture, who lived and hunted here between 8000 and 4000 BCE.[5] Their stone tools and spear points, discovered in the Pinto Basin in the 1930s, suggest that they hunted game and gathered seasonal plants, but little else is known about them.[5] Later residents included the Serrano, the Cahuilla, and the Chemehuevi peoples. All three lived at times in small villages in or near water, particularly the Oasis of Mara in what non-aboriginals later called Twentynine Palms. They were hunter-gatherers who subsisted largely on plant foods supplemented by small game, amphibians, and reptiles while using other plants for making medicines, bows and arrows, baskets, and other articles of daily life.[6] A fourth group, the Mojaves, used the local resources as they traveled along trails between the Colorado River and the Pacific coast. In the 21st century, small numbers of all four peoples live in the region near the park; the Twentynine Palms Band of Mission Indians, descendants of the Chemehuevi, own a reservation in Twentynine Palms.[7]

In 1772, a group of Spaniards led by Pedro Fages, made the first European sightings of Joshua trees while pursuing native converts to Christianity who had run away from a mission in San Diego. By 1823, the year Mexico achieved independence from Spain, a Mexican expedition from Los Angeles, in what was then Alta California, is thought to have explored as far east as the Eagle Mountains in what later became the park. Three years later, Jedediah Smith led a group of American fur trappers and explorers along the nearby Mojave Trail, and others soon followed. Two decades after that, the United States defeated Mexico in the Mexican–American War (1846–48) and took over about half of Mexico's original territory, including California and the future parkland.[8]

After 1870

In 1870, non-natives began grazing cattle on the tall grasses that grew in the park. In 1888, a gang of cattle rustlers moved into the region near the Oasis of Mara. Led by brothers James. B. and William S. McHaney, they hid stolen cattle in a box canyon at Cow Camp.[9] Throughout the region, ranchers dug wells and built rainwater catchments called "tanks", such as White Tank and Barker Dam.[10] In 1900,[11] C. O. Barker, a miner and cattleman, built the original Barker Dam, later improved by William "Bill" Keys, a rancher.[12] Grazing continued in the park through 1945.[10] Barker Dam was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 1975.[11]

Between the 1860s and the 1940s, miners worked about 300 pit mines, mostly small, in what later became the park.[13] The most successful, the Lost Horse Mine, produced gold and silver worth about $5 million in today's currency.[14] Johnny Lang and others, the original owners of the Lost Horse Mine, installed a two-stamp mill to process ore at the site, and the next owner, J.D. Ryan, replaced it with a 10-stamp steam-powered mill.[14] Ryan pumped water from his ranch to the mill and cut timber from the nearby hills to heat water to make steam.[14] Most of the structures associated with the mine fell apart, and for safety reasons the National Park Service plugged the mine, which had collapsed.[14] The Desert Queen Mine on Keys' Desert Queen Ranch was another productive gold mine.[13] In the early 1930s, Keys bought a gasoline-powered two-stamp mill, the Wall Street Mill, and moved it to his ranch to process ore.[15] The ranch and mill were added to the NRHP in 1975[15][16] and the mine in 1976.[17] Some of the mines in the park yielded copper, zinc, and iron.[13]

On August 10, 1936, after Minerva Hoyt and others persuaded the state and federal governments to protect the area, President Franklin D. Roosevelt used the power of the 1906 Antiquities Act to establish Joshua Tree National Monument. It protected about 825,000 acres (334,000 ha).[18] In 1950, the size of the park was reduced by about 290,000 acres to open the land to more mining.[19] The park was elevated to a National Park on October 31, 1994, by the Desert Protection Act, which also added 234,000 acres to the park.[20]

Geography and botany

Mojave Desert

The higher and cooler Mojave Desert is the special habitat of Yucca brevifolia, the Joshua tree for which the park is named. It occurs in patterns from dense forests to distantly spaced specimens. In addition to Joshua tree forests, the western part of the park includes some of the most interesting geologic displays found in California's deserts. The dominant geologic features of this landscape are hills of bare rock, usually broken up into loose boulders. These hills are popular among rock climbing and scrambling enthusiasts. The flatland between these hills is sparsely forested with Joshua trees. Together with the boulder piles and Skull Rock, the trees make the landscape otherworldly. Temperatures are most comfortable in the spring and fall, with an average high/low of 85 and 50 °F (29 and 10 °C) respectively. Winter brings cooler days, around 60 °F (16 °C), and freezing nights. It occasionally snows at higher elevations. Summers are hot, over 100 °F (38 °C) during the day and not cooling much below 75 °F (24 °C) until the early hours of the morning.[21]

Joshua trees dominate the open spaces of the park, but in among the rock outcroppings are piñon pine, California juniper (Juniperus californica), Quercus turbinella (desert scrub oak), Quercus john-tuckeri (Tucker's oak), and Quercus cornelius-mulleri (Muller's oak).[22] These communities are under some stress, however, as the climate was wetter until the 1930s, with the same hot and dry conditions that provoked the Dust Bowl affecting the local climate. These cycles were nothing new, but the original vegetation did not prosper when wetter cycles returned. The difference may have been human development. Cattle grazing took out some of the natural cover and made it less resistant to the changes. But the bigger problem seems to be invasive species, such as cheatgrass, which during wetter periods fill in below and among the pines and oak. In drier times, they die back, but do not quickly decompose. This makes wildfires hotter and more destructive, which kills some of the trees that would have otherwise survived. When the area regenerates, these non-native grasses form a thick layer of turf that makes it harder for the pine and oak seedlings to get a roothold.

Colorado Desert

Below 3,000 feet (910 m), the Colorado Desert encompasses the eastern part of the park and features habitats of Creosote bush scrub, Ocotillo, desert Saltbush and mixed scrub including Yucca and Cholla cactus (Cylindropuntia bigelovii). There are areas of such cactus density they appear as natural gardens. The lower Coachella Valley is on the southeastern side of the Park with sandy soil grasslands and desert dunes.

The only palm native to California, the California Fan Palm (Washingtonia filifera), occurs naturally in five oases in the park, rare areas where water occurs naturally year round and all forms of wildlife abound.[4]

Geology

The park's oldest rocks, Pinto gneiss among them, are 1.7 billion years old. They are exposed in places on the park's surface in the Cottonwood, Pinto, and Eagle mountains. Much later, from 250 to 75 million years ago, tectonic plate movements forced volcanic material toward the surface at this location and formed granites, including monzogranite common to the Wonderland of Rocks, parts of the Pinto, Eagle, and Coxcomb mountains, and elsewhere. Erosion eventually exposed the harder rocks, gneiss and granite, in the uplands and reduced the softer rocks to debris that filled the canyons and basins between the ranges. The debris, moved by gravity and water, formed alluvial fans at the mouths of canyons as well as bajadas where the alluvial fans overlapped.[23]

The rock formations of Joshua Tree National Park owe their shape partly to groundwater, which filtered through the roughly rectangular joints of the monzonite and eroded the corners and edges of blocks of stone, and to flash floods, which washed away covering ground and left piles of rounded boulders.[24] These prominent outcrops are known as inselbergs.[25]

Of the park's six blocks of mountains, five—the Little San Bernardino, Hexie, Pinto, Cottonwood, and Eagle—are among the Transverse Ranges, which trend generally east–west in locations between the Eagle Mountains on the east and the northern Channel Islands, in the Pacific Ocean west of Santa Barbara, on the west. Tectonic forces along the San Andreas Fault system compressed and lifted the crust material that formed these ranges. The San Andreas Fault itself passes southwest of the park, but related parallel faults including the Dillon, Blue Cut, and Pinto, run through the park, and movements along them have caused earthquakes. The easternmost range in the park, the Coxcomb Mountains, runs generally north–south and is part of the Basin and Range Province.[23]

Recreation

.jpg)

Camping

Nine established campgrounds exist in the park, two of which (Black Rock Campground and Cottonwood Campground) provide water and flush toilets. A fee is charged per night for each camping spot.[26] Reservations are accepted at Black Rock Campground, Cottonwood Campground, Indian Cove Campground, and Jumbo Rocks Campground for October through May, while the other campgrounds are first-come, first-served. Backcountry camping, for those who wish to backpack, is permitted with a few regulations.[27]

Hiking

There are several hiking trails within the park, many of which can be accessed from a campground. Shorter trails, such as the one mile hike through Hidden Valley, offer a chance to view the beauty of the park without straying too far into the desert. A section of the California Riding and Hiking Trail meanders for 35 miles (56 km) through the western side of the park.[28] The lookout point at Keys View, towards the south of the park, offers views of the Coachella Valley, the Salton Sea, the San Andreas Fault, the Santa Rosa Mountains, and the city of Palm Springs.[29]

Nature walks inside the park include:

- Hidden Valley

- Indian Cove

- Cholla Cactus Garden

Longer trails include:

- Boy Scout Hiking and Equestrian Trail

- Contact Mine

- Fortynine Palms Oasis

- Lost Horse Mine

- Lost Palms Oasis

- Ryan Mountain

- Warren Peak

Due to graffiti on at least 17 sites on trails, officials have closed them to the public. The closed sites include Native American sites, at the Southern California park's Rattlesnake Canyon and Barker Dam. They blame the increase in vandalism on the increased use of social media.[30]

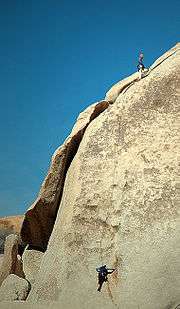

Climbing

The park is popular with rock climbers and was originally a winter practice area while Yosemite Valley and other parts of the Sierra Nevada were snowbound, but later became an area of interest in its own right. There are thousands of named climbing routes, at all levels of difficulty. The routes are typically short, the rocks being rarely more than 230 ft (70 m) in height, but access is usually a short, easy walk through the desert, and it is possible to do a number of interesting climbs in a single day. The rocks are all composed of quartz monzonite, a very rough type of granite made even more so as there is no snow or ice to polish it as in places like Yosemite.

Some routes are permanently closed while others are closed temporarily to protect sensitive wildlife in certain seasons. Climbing and bouldering routes that are permanently closed include Energy Crisis, the Schwarzenegger Wall, Zombie Woof Rock, the Maverick Boulder formation, Pictograph Boulder, Shindig, Lonely Stones Area #3, The Shipwreck formation, Indian Wave Boulders (except for Native Arete), and Wormholes. As of March 14, 2018, seasonal closures include the Slatanic Area, Towers of Uncertainty, Patagonia Pile, and Jerry's Quarry.[31]

Driving

The paved main road allows visitors to drive to major attractions and through the park. The unpaved roads may require a vehicle with high ground clearance, and four-wheel drive. An example is the Geology Tour Road in the center of the park. Visitors with a four-wheel drive vehicle can use this road for a self-guided tour with stops that describe the region's geology.[32]

Birding

There are over 250 species of bird in the park including resident desert birds such as the greater roadrunner and cactus wren as well as mockingbirds, Le Conte's thrasher, verdin and Gambel's quail. There are also many transient species that may spend only one or two seasons in the park. Noted birding spots in the park include: fan palm oases, Barker Dam and Smith Water Canyon. Queen Valley and Lost Horse Valley also provide good birding but with a different range of species because of the lack of water. These are often good places to see ladder-backed woodpecker and oak titmouse. A USGS Bird Checklist [33] of "what, when, and status" has 239 species listed for the park.[33]

Astronomy

Joshua Tree is a popular observing site in Southern California for amateur astronomy and stargazing,[34] along with nearby Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. The park is well known for its naturally dark night skies, which are far away from and largely free of the light pollution typical in the urban areas. The park's elevation and dry desert air, along with the relatively stable atmosphere in the region, often make for excellent seeing conditions.

On clear nights around new moon, the sky darkness of Joshua Tree is rated a Class 2–4 on the Bortle scale.[35][36] This ranges from an "average dark sky" (Class 2) in the easternmost region of the park to a sky quality typical of a rural/suburban transition (Class 4) in the western regions near Palm Springs.[36][37] In the easternmost regions of the park, visitors with optimal vision can expect to see the Andromeda (M31) and Triangulum (M33) galaxies with unaided eyes. The central Milky Way appears highly structured to the naked eye from this site, and zodiacal light appears as a faint yellowish glow when visible.[37] In the western regions of the park, the Andromeda Galaxy is still visible, and only the brightest structures around the Galactic Center of the Milky Way can be distinguished; zodicial light is visible halfway to the zenith.[37]

Wildlife

Many animals make their homes in Joshua Tree. Birds, lizards, and ground squirrels are most likely to be seen because they are largely active during the day. However, it is at night that desert animals come out to roam. Mostly nocturnal animals include snakes, bighorn sheep, kangaroo rats, coyotes, lynx, and black-tailed jackrabbits.[38]

Animals that thrive in Joshua Tree often have special adaptations for dealing with limited water and high summer temperatures. The smaller mammals and all reptiles take refuge from the heat underground. Desert mammals make more efficient use of their bodies’ water supply than does the human body. Reptiles are physiologically adapted to getting along with little water, and birds can fly to water sources when they need to drink. Nevertheless, the springs and seeps in the park are necessary to the survival of many animals.[38]

Most of the reptiles and many small rodents and insects go into an inactive state of hibernation during the winter. However, winter is the time of greatest bird concentrations in the park, because of the presence of many migrant species.[38]

A good place to view wildlife is at Barker Dam, a short hike from a parking area near Hidden Valley. Desert bighorn sheep and mule deer sometimes stop by the dam for a drink. Tours of the Barker Dam area are available.

Wildlife of the park includes:

- The California tree frog, Pseudacris cadaverina, is found in the rocky, permanent water sources created by the Pinto Fault along the northern edge of the park.[39]

- The red-spotted toad, Bufo punctatus, is a true denizen of the desert, where it spends most of its life underground. Found from one end of the park to the other, it appears after good, soaking rains.[39]

- Golden eagles hunt in the park regularly.[40]

- The roadrunner is an easily recognized resident.[40]

- The call of Gambel's quail can frequently be heard.[40]

- The tarantula Aphonopelma iodium, the green darner Anax junius, and the giant desert scorpion Hadrurus arizonensis are arthropods that can grow to be more than 4 inches (10 cm) long.[41]

- The yucca moth Tegeticula paradoxa is responsible for pollinating the Joshua trees after which the park is named.[41]

Wilderness

Of the park's total land area of 790,636 acres (319,959 ha), 429,690 acres (173,890 ha) are designated wilderness and managed by the National Park Service (NPS) in accordance with the Wilderness Act. The NPS requires registration for overnight camping at specific locations called registration boards. Other requirements include the use of a camp stove (since open campfires are prohibited) and employing Leave No Trace camping techniques (also known as "pack it in, pack it out").[42] Although bicycles are not allowed in wilderness areas, horses are, but a permit must be obtained in advance for travel in the backcountry. Cellular signals are weak to non-existent and should not be depended on while visiting the park.

Vandalism

On April 1, 2015, graffiti artist André was convicted and fined for vandalizing ancient rock formations in the park.[43] André posted photos of his vandalizations on Instagram. The web site Modern Hiker and its readers aided the National Park Service in tracking down and identifying André's vandalism.[44] Before the conviction, André attempted to silence the reporting with legal threats.[45]

In popular culture

In 1972, the album cover photos for Eagles were shot in Joshua Tree National Park.[46]

In 1973, Phil Kaufman attempted to cremate singer/songwriter Gram Parsons' remains here.[47] To this day, people continue to visit in tribute to Parsons.

In 1987, Irish rock band U2 released their fifth studio album, The Joshua Tree, named after a tree with which the band were photographed near Darwin, California. It is a common misconception that the site of this tree is within Joshua Tree National Park, when in fact it is over 200 miles away.

In 1994, American Tejano singer Selena recorded her music video for "Amor Prohibido" at Joshua Tree National Park.[48]

The black comedy crime film Seven Psychopaths (2012) was partly filmed in the park,[49] as were many other film and television productions[50] beginning with Borderland (1937), a Hopalong Cassidy feature.[51]

In 2016, Donald Glover (a.k.a. Childish Gambino) performed six sold-out shows in Joshua Tree in promotion of his new album, "Awaken, My Love!". The three-day event went by the name Pharos.[52]

In 2017, American rock band Walk the Moon recorded the video "One Foot" in the park during that summer's solar eclipse.[53]

See also

References

![]()

- 1 2 Land Resources Division (December 31, 2016). "National Park Service Listing of Acreage (summary)" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service.

- ↑

- 1 2 "A Desert Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- 1 2 "Pinto Culture". National Park Service. February 28, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ↑ Hunter, Charlotte (March 22, 2016). "American Indians". National Park Service. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ↑ Dilsaver 2015, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Dilsaver 2015, pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Eggers 2004, pp. 33–34.

- 1 2 "Cowboys". National Park Service. February 28, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- 1 2 Chappell, Gordon (June 11, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form: Barker Dam". National Park Service. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ↑ Dilsaver 2015, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 Dilsaver 2015, pp. 33–39.

- 1 2 3 4 Spoo, Melanie (February 28, 2015). "Lost Horse Mine". National Park Service. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- 1 2 Chappell, Gordon (June 10, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Wall Street Mill" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ↑ Chappell, Gordon (1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Keys Desert Queen Ranch" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ↑ Chappell, Gordon (1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Desert Queen Mine" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ↑ Zarki 2015, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Zarki 2015, p. 92.

- ↑ "Park History". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Operating Hours & Seasons". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS.

- ↑ Southern California Plant Communities 15. Joshua Tree woodland

- 1 2 Dilsaver 2015, pp. 16–19.

- ↑ "Geologic Formations". Joshua Tree National Park. January 4, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ↑ Trent, D. D. (April 1984). "Geology of the Joshua Tree National Monument". California Geology. 37. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Camping". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ↑ "California Resort Life". CaliforniaResortLife.com.

- ↑ "Hiking". National Park Service. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ↑ Kaiser 2010, pp. 142–43.

- ↑ "Graffiti Force Closure Of Joshua Tree Park Sites". AP. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Climbing Closures". nps.gov. National Park Service. March 14, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Geology Motor Tour". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- 1 2 "USGS Bird Checklist". Archived from the original on July 31, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Stargazing". Joshua Tree National Park. NPS. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ↑ "ClearDarkSky Light Pollution Map". ClearDarkSky.com. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- 1 2 "Light Lollution Map". lightpollutionmap.info. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- 1 2 3 "Bortle Dark Sky Scale". handprint.com. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- 1 2 3 "Animals". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- 1 2 "Amphibians". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Birds". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- 1 2 "Insects, Spiders, Centipedes, Millipedes". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Backpacking". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ↑ Spiers, Katherine (April 15, 2015) "Artist "Mr. Andre" Pays Fine For Vandalizing Joshua Tree National Park." KCET.org. (Retrieved April 16, 2015.)

- ↑ Schreiner, Casey (February 27, 2015). "Is Mr. Andre tagging in Joshua Tree?". Modern Hiker.

- ↑ Schreiner, Casey (March 10, 2015). "Mr. Andre issues legal threat to Modern Hiker". Modern Hiker.

- ↑ Simmons, Bill. "The Eagles' Greatest Hit". Grantland. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ↑ "What's up with the strange end of country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons?" from The Straight Dope

- ↑ Villarreal, Yezmen. "28 Things You Didn't Know About Selena". BuzzFeed. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Seven Psychopaths (2012) Filming & Production". imdb.com. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Learn About the Park: History & Culture > Stories > Movies". nps.gov. National Park Service. January 31, 2017. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Earliest Titles With Location Matching 'Joshua Tree National Park, California, USA'". imdb.com. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ↑ "A First Person Account of Childish Gambino's Spectacular Pharos Event". PigeonsandPlanes. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ↑ Stubblebine, Allison. "Walk the Moon Release High-Energy Single & Video, 'One Foot': Watch". billboard. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

Works cited

- Dilsaver, Lary M. (March 2015). Joshua Tree National Park: A History of Preserving the Desert (PDF). National Park Service. OCLC 912308073. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- Eggers, Margaret (2004). Mining History and Geology of Joshua Tree National Park. San Diego Association of Geologists. ISBN 978-0-916251-70-3.

- Kaiser, James (2010). Joshua Tree: The Complete Guide (4th ed.). Destination Press. ISBN 978-0-9825172-3-9.

- Zarki, Joseph W. (2015). Images of America: Joshua Tree National Park. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-3281-7.

Further reading

- Birds, Joshua Tree National Park Association

- "Joshua Tree" (2001), California's Gold. VHS videorecording by Huell Howser Productions, in association with KCET/Los Angeles. OCLC 655384402

External links

- Official website

- Map of Joshua Tree National Park (archive)

- Geologic Travel Guide: article by the American Geological Institute

- "Keys Ranch: Where Time Stood Still", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Joshua Tree National Park Bird Checklist with seasonal info.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hidden Valley