National Park of American Samoa

| National Park of American Samoa | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

Pola Island on Tutuila | |

| |

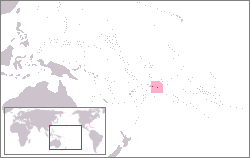

| Location | American Samoa, United States |

| Nearest city | Pago Pago |

| Coordinates | 14°15′30″S 170°41′00″W / 14.25833°S 170.68333°WCoordinates: 14°15′30″S 170°41′00″W / 14.25833°S 170.68333°W |

| Area | 13,500 acres (55 km2)[1] |

| Established | October 31, 1988 |

| Visitors | 69,468 (in 2017)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website |

Official website |

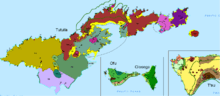

The National Park of American Samoa is a national park in the United States territory of American Samoa, distributed across three islands: Tutuila, Ofu, and Ta‘ū. The park preserves and protects coral reefs, tropical rainforests, fruit bats, and the Samoan culture. Popular activities include hiking and snorkeling. Of the park's 13,500 acres (5,500 ha), 9,000 acres (3,600 ha) is land and 4,500 acres (1,800 ha) is coral reefs and ocean.[3] The park is the only American National Park Service system unit south of the equator.[4]

History

The National Park of American Samoa was established on October 31, 1988 by Public Law 100-571[5] but the NPS could not buy the land because of traditional communal land system. This was resolved on September 9, 1993, when the National Park Service entered into a 50-year lease for the park land from the Samoan village councils. In 2002, Congress approved a thirty percent expansion on Olosega and Ofu islands.[6]

In 2009 an earthquake and tsunami produced several large waves, resulting in 34 confirmed deaths, more than a hundred injuries and the destruction of about 200 homes and businesses. The park encountered major damage. The visitor center and main office were destroyed but there was only one reported injury among the NPS staff and volunteers.[7]

Tutuila

The Tutuila unit of the park is on the north end of the island near Pago Pago. It is separated by Mount Alava (1,610 feet (490 m)) and the Maugaloa Ridge and includes the Amalau Valley, Craggy Point, Tafeu Cove, and the islands of Pola and Manofa. It is the only part of the park accessible by car and attracts the vast majority of visitors to the area. The park lands include a trail to the top of Mount Alava and historic World War II gun emplacement sites at Breakers Point and Blunt's Point.[8] The trail runs along the ridge in dense forest, north of which the land slopes steeply away to the ocean.[9]

Manua Island group

Ofu Unit

Ofu island is only accessible via small fisherman boats from Ta'u island. Accommodations are available on Ofu.

Ta‘ū Unit

Ta‘ū island can be reached by a flight from Tutuila to Fiti‘uta village on Ta‘ū. Accommodations are available on Ta‘ū. A trail runs from Saua around Si’u Point to the southern coastline and stairs to the 3,170-foot (970 m) summit of Lata Mountain.

Biodiversity

Because of its remote location, diversity among the terrestrial species is low. Approximately 30% of the plants and one bird species (the Samoan starling) are endemic to the archipelago.[10]

Fauna

Three species of bat are the only native mammals: two large fruit bats (Samoa flying fox and white-naped flying fox) and a small insectivore, the Pacific sheath-tailed bat. They serve an important role in pollinating the island's plants. The sheath-tailed bat was nearly eliminated by Cyclone Val in 1991. Native reptiles include the pelagic gecko, Polynesian gecko, mourning gecko, stump-toed gecko, Pacific boa and seven skink species.[11] A major role for the park is to control and eradicate invasive plant and animal species such as feral pigs, which threaten the park's ecosystem. There are several bird species, the most predominant being the wattled honeyeater, Samoan starling, and Pacific pigeon.[12] Other unusual birds include the Tahiti petrel, the spotless crake, and the rare (in this locality) many-colored fruit dove.[10]

Flora

The islands are mostly covered by tropical rainforest, including cloud forest on Ta'u and lowland ridge forest on Tutuila. Most plants arrived by chance from Southeast Asia. There are 343 flowering plants, 135 ferns and about 30% are endemic plant species.

Marine

The surrounding waters are filled with a diversity of marine life, including sea turtles, humpback whales, over 950 species of fish, and over 250 coral species. Some of the largest living coral colonies (Porites) in the world are at Ta'u island.

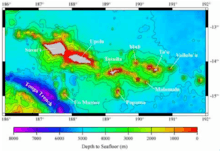

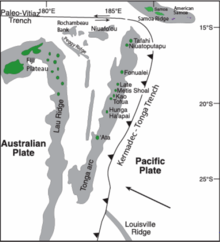

Geology

The volcanic islands of Samoa that dominate the acreage of the national park are composed of shield volcanoes which developed from a hot spot on the Pacific Plate, emerging sequentially from west to east. Tutulia, the largest and oldest island, probably dates from the Pliocene Epoch, approximately 1.24 to 1.4 million years ago, while the smaller islands are most likely Holocene in age.

The islands are not made up of individual volcanoes, but are rather composed of overlapping and superimposed shield volcanoes built by basalt lava flows. Much of the lava that erupted has since broken into angular fragments known as breccia. The volcanoes emerged from the intrusion of basaltic dikes from a rift zone on the ocean floor during the Pliocene Epoch, and were heavily eroded during the Pliocene and early Pleistocene Epochs, leaving behind trachyte plugs and exposed outcrops of volcanic tuff throughout the park. Ta'u island, the youngest of the islands included within the national park, is all that remains from the collapse of a shield volcano during Holocene time. This collapse produced sea cliffs over 3,000 feet high on the north side of the island, some of the highest such escarpments in the world.

While the Samoan islands have not shown evidence of volcanism for many years, the Samoa hotspot beneath the islands continues to give indications of activity, with a submarine eruption detected just east of American Samoa in 1973. The Vailulu'u Seamount, located east of Ta'u, is a future Samoan island developing from submarine lava flows, continuing the eastward progress of volcanic development from the hotspot below the islands. The lava flows forming the seamount have been dated by radiometric methods to between 5 and 50 years, during which time the seamount has risen 14,764 feet from the ocean floor.

Evidence exists of past submarine and surface landslides as a result of weathering and other forms of erosion of the rocks and soil making up the islands. On Ta'u island, an inland escarpment known as Liu Bench (a feature of mass wasting) threatens to slump into the nearby ocean, an event which could produce a tsunami strong enough to devastate the island of Fiji to the southeast.[13]

Olivine basalts were extruded from a N. 70° E. trending rift zone, oriented along the current Afono and Masefay bays of Tutuila, in the Pliocene or earliest Pleistocene. The Masefau dike complex and talus breccias are remnants of this rifting. Development of the Taputapu, Pago, Alofau, and Olomoana shield domes followed long parallel fissures followed, but when the Pago and Alofau summits collapsed, calderas were formed. Thick tuffs were deposited in the Pago caldera, and the southern rim was buried by lavas composed of picritic basalts, andesites, and trachytes. Subsequent erosion in Early to Middle Pleistocene enlarged the calderas, the Pago River in particular carved a deep canyon, the forerunner of today's Pago Pago Bay. A submarine shelf formed from the erosional runoff, allowing for the development of coral reefs before the island was submerged 600 to 2000 feet. Sea level fluctuations continued in the Middle to Late Pleistocene. A barrier reef formed, was submerged 200 feet, before emerging 50 feet, leaving sea caves above sea level. Leone volcanics erupted in recent time generating tuff cones undersea, such as Aunuu Island, and cinder cones on land. The pahoehoe flows buried the submerged barrier reef, enlarging the island by 8 square miles. The island has since emerged another 5 feet.[14]

Ofu and Olosega are the remains of a single basaltic volcano, 4 miles north to south and 6 miles east to west, which formed in the Pliocene to Early Pleistocene. Remnants of one half of the caldera, ponded flows, form the north center portion of Ofu. The steepest cliffs, 600 feet high, are found on this north coast. The Ofu-Olosega island group formed along the same N. 70° W. trending rift which formed Tau, another single basaltic dome. The remnant of Tau's caldera is found on the south coast. A 2000-foot cliff marks the north coast of this island.[14]:1313–1318

Upolu formed as an elongated basaltic shield volcano due to Late Tertiary to Late Pliocene rifting along a S. 70° E. trend. Remnants of these eruptions are found as inliers and monadnocks forming Mt. Tafatafao, Mt. Vaaifetu, and Mt. Spitzer. Volcanic activity renewed in the Middle Pleistocene along the same rift trend, with olivine basalt pahoehoe and aa flowing northward and southward from a point 8 miles west from the center of the island. Pleistocene cinder cones trending east and west, are aligned along the center axis of the island. Savai'i lies along this same rift trend, its surface marked by Quaternary lava flows. Examples include the olivine basalt pahoehoe which emerged from Mount Matavanu from 1905 to 1911, and the Mauga Afi chain of spatter cones of 1902.[14]:1318–1328

Threats

The coral reefs are under significant threat due to rising ocean temperatures and carbon dioxide concentration, as well as sea level rise. As a result of these and other stresses, the corals that form the reefs are projected to be lost by mid-century if carbon dioxide concentrations continue to rise at their current rate.[15]

See also

- List of national parks of the United States

- List of birds of Samoa

- Old Vatia, an important archaeological site in the park

- Rose Atoll

- Samoan plant names

- Tonga Trench

References

- ↑ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-05.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ↑ "The National Parks: Index 2009–2011". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/npsa/learn/news/fact-sheet.htm National Park of American Samoa. National Park Service. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Public Law No: 100-571". Library of Congress: THOMAS. 1988-10-31. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ "Public Law No: 107-336". Library of Congress: THOMAS. 2002-12-16. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ "American Samoa Earthquake and Tsunami Damage" (PDF). Department of the Interior. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-23. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ "Hiking and Beachwalking". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ National Geographic Guide to the National Parks of the United States. National Geographic Society. 2006. ISBN 0-7922-5322-1.

- 1 2 Hart, Risé (2005-02-14). "Pacific Island Network Vital Signs Monitoring Plan—Appendix A: National Park of American Samoa Resource Overview" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ National Park home page, retrieved 2009-10-01

- ↑ Craig, P. "Natural History Guide to American Samoa" (PDF). National Park of American Samoa, Department Marine and Wildlife Resources, American Samoa Community College. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ Ann G. Harris, et al., The Geology of National Parks,(Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt, 2004)

- 1 2 3 Stearns, Harold (1944). "Geology of the Samoan Islands". Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. 55 (November): 1312–1313. doi:10.1130/gsab-55-1279.

- ↑ Report to the Congress Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States, 2009

Bibliography

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Park of American Samoa. |

- National Park Service: National Park of American Samoa

- National Park Service map of the Manu‘a Islands showing the present park boundaries (pdf).

- Seacology National Park of American Samoa projects Seacology

- Birds of the National Park of American Samoa