British Americans

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

Self reported: 40,234,652 (2009) [1][2] 13.0% of the total U.S. population. Other estimates: 72,065,000 [3] 23.3% of the total U.S. population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

Throughout the entire United States except parts of the Midwest Predominantly in the South, Northeast and West regions. | |

| Languages | |

| English (American English, British English), Goidelic languages, Scots, Welsh | |

| Religion | |

|

Christian Mainly Protestant (especially Baptist, Congregationalist, Episcopalian, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Quaker) and to a lesser extent Catholic and Mormon | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

.png)

British Americans usually refers to Americans whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland). Unlike similar terms, such as African American, Greek American, Italian American, or Chinese American individuals seldom self-designate as British American (1,172,050 chose it in the 2009 American Community Survey); it is primarily a demographic or historical research category for people who have at least partial descent from peoples of Great Britain and the modern United Kingdom, i.e. English Americans, Scottish Americans, Welsh Americans, Scotch-Irish Americans, Manx Americans, and to an extent, people who identify simply as "Americans".

According to American Community Survey in 2009, Americans reporting one of the British ancestries number 40,234,652, or 13.0% of the total U.S. population, a significant drop from the 1980 United States Census where 49,598,035 reported as having English ancestry and 61,311,449 reported as having British ancestry.[2] Using the self reported 2010 census figures British Americans are the largest European ancestry group of all. However, this figure is likely a serious undercount, as a large proportion of Americans of British descent have a tendency (since the introduction of a new 'American' category in the 2000 census) to identify as simply Americans[4][5][6][7] or if of mixed European ancestry, identify with a more recent and differentiated ethnic group.[8] Eight out of the ten most common surnames in the United States are of British origin.[9]

Occasionally the term is also used in an entirely different (although possibly overlapping) sense to refer to people who are dual citizens of both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Identity

British Americans have Cornish, English, Scottish, Ulster Scots, and/or Welsh family heritages, or came from Canada where their ancestors were of British descent, and are those Americans who were British born. Immigrants from Canada of British ancestry tend to call themselves Canadian Americans. Similarly, most British Americans tend to differentiate to being specifically Cornish, English, Northern Irish, Scottish, Welsh or ethnic minorities (e.g. Pakistani Scottish) and do not identify with the UK as a whole, therefore tending not to refer to themselves as British American (see: Cornish American, English American, Scottish American, Welsh American, or Scots-Irish American) and settlers of British heritage from other former British territories like Australia, New Zealand and South Africa also consider themselves by their nationalities, Australian Americans, New Zealand Americans and South African-Americans.

Number of British Americans

| Number of British Americans (ancestry) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Ref. | Population | % of the United States population | |||

| 1980 | [10][11] | English: 49,598,035 Scottish: 10,048,816 Scots-Irish: ND Welsh: 1,664,598 |

32.56% | |||

| 1990 | [12] | English: 32,651,788 Scottish: 5,393,581 Scotch-Irish: 5,617,773 Welsh: 2,033,893 |

18.4% | |||

| 2000 | [13] | English: 24,515,138 Scottish: 4,890,581 Scotch-Irish: 4,319,232 Welsh: 1,753,794 British: 1,085,720 |

12.9% | |||

| 2010 | [14] | English: 25,927,345 Scottish: 5,460,679 Scotch-Irish: 3,257,161 Welsh: 1,793,356 British: 1,181,557 |

||||

1790 Census

The ancestry of the 3,929,214 population in 1790 has been estimated by various sources by sampling last names in the very first United States official census and assigning them a country of origin.[15] The estimate results indicate that people of British ancestry made up about 62% of the total population or 74% of the European American population. Some 81% of the total United States population was of European heritage.[16] Around 757,208 were of African descent with 697,624 being slaves. Of the remaining population, more than 75% was of British origin.[17]

1980 Census

In the Twentieth 1980 United States Census, 61.3 million (61,311,449) Americans reported British ancestry.

The total U.S population in 1980 was 226,545,805 and was the first census-form that asked people's ancestry.[18]

These include: In 1980, the total census reported that British ancestry was (32.56%) of the total U.S. population. Triple ancestry response:English-Irish-Scotch: 897,316. This article does not include the Irish, as part of British nationality. There are still people of Northern Ireland which is part of the UK. Also when a lot of the Irish came over to the US, all were British citizens to up 1949. Furthermore people who emigrated to the US from Northern Ireland are not included but lumped with Irish ethnicity, this gives another massive distortion. Not all the Irish were anti British, as can be seen with the strong links between Ireland and the UK today, these links some of them would of carried over to the US. https://sluggerotoole.com/2015/07/28/the-irish-in-britain-no-longer-need-to-think-of-themselves-as-emigrants/. This link shows people of Irish descent and emigrants to Britain did not see themselves any different from the British in the UK, so this would be the case for "Irish" Americans.

There are no concrete figures for the Scots-Irish and some group responses were under-counted, but in 1980, 29,828,349 people claimed Irish and another ethnic ancestry. These figures make British Americans the largest "ethnic" group in the U.S. and would have naturally increased in population with more people of British origin than in 1980. This is true when counted collectively (the Census Bureau does give the choice to count them collectively as one ancestry, and also count them in a separate ethnic group, that is English, Scottish, Welsh or Scots-Irish). In 2000, Germans and Irish were the largest self-reported ethnic groups in the nation.

1990 Census

The Twenty-first 1990 United States Census.[19]

2000 Census

The Twenty-Second 2000 United States Census, 36.4 million Americans reported British ancestry.[20]

Most of the population who stated their ancestry as "American" are said to be of old colonial British stock.

- American ethnicity 20,625,093 (7.3%) Census

| Comparison between the 1790 and 2000 census | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 estimates[21] | 2000 Census[22] | ||||

| Ancestry | Number | % of total | Ancestry | Number | % of total |

| English | 2,605,699 | 66.3 | German | 42,885,162 | 15.2 |

| Other Race | 756,770 | 19.3 | African | 36,419,434 | 12.9 |

| Scottish | 221,562 | 5.6 | Irish | 30,594,130 | 10.9 |

| German | 176,407 | 4.5 | English | 24,515,138 | 8.7 |

| Dutch | 78,959 | 2.0 | Mexican | 20,640,711 | 7.3 |

| Irish | 61,534 | 1.6 | Italian | 15,723,555 | 5.6 |

| French | 17,619 | 0.4 | French | 10,846,018 | 3.9 |

| Other European | 10,664 | 0.3 | Hispanic | 10,017,244 | 3.6 |

| Polish | 8,977,444 | 3.2 | |||

| Scottish | 4,890,581 | 1.7 | |||

| Dutch | 4,542,494 | 1.6 | |||

| Norwegian | 4,477,725 | 1.6 | |||

| Scotch-Irish | 4,319,232 | 1.5 | |||

| United States | 3,929,214 [23] | 100 | United States | 281,421,906 | 100 |

Distribution

Following are the top 10 highest percentages of people of English, Scottish and Welsh ancestry, in U.S. communities with 500 or more total inhabitants (for the total list of the 101 communities, see the reference): (see also Maps of American ancestries)[24][25][26]

English

- Hildale, UT 66.9%

- Colorado City, AZ 52.7%

- Milbridge, ME 41.1%

- Panguitch, UT 40.0%

- Beaver, UT 39.8%

- Enterprise, UT 39.4%

- East Machias, ME 39.1%

- Marriott-Slaterville, UT 38.2%

- Wellsville, UT 37.9%

- Morgan, UT 37.2%

Scottish

- Lonaconing, MD town 16.1%

- Jordan, IL township 12.6%

- Scioto, OH township 12.1%

- Randolph, IN township 10.2%

- Franconia, NH town 10.1%

- Topsham, VT town 10.0%

- Ryegate, VT town 9.9%

- Plainfield, VT town 9.8%

- Saratoga Springs, UT town 9.7%

- Barnet, VT town 9.5%

Welsh

- Malad City, ID city 21.1

- Remsen, NY town 14.6

- Oak Hill, OH village 13.6

- Madison, OH township 12.7

- Steuben, NY town 10.9

- Franklin, OH township 10.5

- Plymouth, PA borough 10.3

- Jackson, OH city 10.0

- Lake, PA township 9.9

- Radnor, OH township 9.8

History

| Immigration from the United Kingdom to the United States 1820 - 2000[27][28][29][30] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | Arrivals | Years | Arrivals | Years | Arrivals |

| 1820-1830 | 27,489 | 1901-1910 | 525,950 | 1981-1990 | 159,173 |

| 1831-1840 | 75,810 | 1911-1920 | 341,408 | 1991-2000 | 151,866 |

| 1841-1850 | 267,044 | 1921-1930 | 339,570 | ||

| 1851-1860 | 423,974 | 1931-1940 | 31,572 | ||

| 1861-1870 | 606,896 | 1941-1950 | 139,306 | ||

| 1871-1880 | 548,043 | 1951-1960 | 202,824 | ||

| 1881-1890 | 807,357 | 1961-1970 | 213,822 | ||

| 1891-1900 | 271,538 | 1971-1980 | 137,374 | ||

| Arrivals | Total (180 yrs) | 5,271,016 | |||

| Prior to 1926, data for "Northern Ireland" was included in Ireland. Since 1925, data for United Kingdom refer to England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. | |||||

Early British emigration

The British diaspora consists of the scattering of British people and their descendants who emigrated from the United Kingdom. The diaspora is concentrated in countries that had mass migration such as the United States and that are part of the English-speaking world. A 2006 publication from the Institute for Public Policy Research estimated 5.6 million British-born people lived outside of the United Kingdom.[31][32]

After the Age of Discovery the British were one of the earliest and largest communities to emigrate out of Europe, and the British Empire's expansion during the first half of the 19th century saw an "extraordinary dispersion of the British people", with particular concentrations "in Australasia and North America".[33]

The British Empire was "built on waves of migration overseas by British people",[34] who left the United Kingdom and "reached across the globe and permanently affected population structures in three continents".[33] As a result of the British colonization of the Americas, what became the United States was "easily the greatest single destination of emigrant British".[33]

Historically in the 1790 United States Census estimate and presently in Australia, Canada and New Zealand "people of British origin came to constitute the majority of the population" contributing to these states becoming integral to the Anglosphere.[34]

Settlement and colonization

An English presence in North America began with the Roanoke Colony and Colony of Virginia in the late-16th century, but the first successful English settlement was established in 1607, on the James River at Jamestown. By the 1610s an estimated 1,300 English people had travelled to North America, the "first of many millions from the British Isles".[35] In 1620 the Pilgrims established the English imperial venture of Plymouth Colony, beginning "a remarkable acceleration of permanent emigration from England" with over 60% of trans-Atlantic English migrants settling in the New England Colonies.[35] During the 17th century an estimated 350,000 English and Welsh migrants arrived in North America, which in the century after the Acts of Union 1707 was surpassed in rate and number by Scottish and Irish migrants.[36]

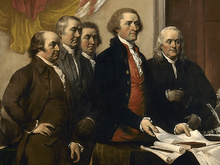

Declaration of independence. The Committee of Five and most of the Founding Fathers had British ancestors.

Declaration of independence. The Committee of Five and most of the Founding Fathers had British ancestors. The National personification of the United States and Great Britain. Uncle Sam embracing John Bull, while Britannia and Columbia hold hands and sit together in the background (1898).

The National personification of the United States and Great Britain. Uncle Sam embracing John Bull, while Britannia and Columbia hold hands and sit together in the background (1898).

The British policy of salutary neglect for its North American colonies intended to minimize trade restrictions as a way of ensuring they stayed loyal to British interests.[37] This permitted the development of the American Dream, a cultural spirit distinct from that of its European founders.[37] The Thirteen Colonies of British America began an armed rebellion against British rule in 1775 when they rejected the right of the Parliament of Great Britain to govern them without representation; they proclaimed their independence in 1776, and subsequently constituted the first thirteen states of the United States of America, which became a sovereign state in 1781 with the ratification of the Articles of Confederation. The 1783 Treaty of Paris represented Great Britain's formal acknowledgement of the United States' sovereignty at the end of the American Revolutionary War.[38]

Today

Nevertheless, longstanding cultural and historical ties have, in more modern times, resulted in the Special Relationship, the exceptionally close political, diplomatic and military co-operation of United Kingdom – United States relations.[39] Linda Colley, a professor of history at Princeton University and specialist in Britishness, suggested that because of their colonial influence on the United States, the British find Americans a "mysterious and paradoxical people, physically distant but culturally close, engagingly similar yet irritatingly different".[40]

American cultural icons

.svg.png) Grand Union Flag was first flown on December 2, 1775. The 13 stripes represent the original British thirteen colonies.

Grand Union Flag was first flown on December 2, 1775. The 13 stripes represent the original British thirteen colonies. The current flag has fifty stars on the flag representing the 50 states.

The current flag has fifty stars on the flag representing the 50 states.

- Harvard was founded by Englishmen who sought to reproduce the environment of academic excellence they experienced at Cambridge University, England where many of the founders of New England have been educated.

- The first public school in America, The Boston Latin School, was founded by Englishman John Cotton, Esq., former Dean of Emmanuel College, Cambridge University, England to replicate a public Latin School in England.

- Yale University was founded by Englishmen who considered Harvard too liberal for the education of New England gentlemen.

- The Declaration of Independence is a creation of British Americans.

- The Constitution of the United States is a creation of British Americans.

- The American Bill of Rights is a creation of British Americans.

- The American system of government: a Constitutional Republic with a separation of executive, legislative, and judicial powers is a creation of British Americans.

- Most American Presidents, Senators, Congressmen, Governors and Ivy League University Presidents have been British Americans.

The Grand Union Flag is considered to be the first national flag of the United States . This flag consisted of 13 red and white stripes with the British Union Flag of the time (before the inclusion of St. Patrick's cross of Ireland) in the canton. The flag was first flown on December 2, 1775 by John Paul Jones (then a Continental Navy lieutenant) on the ship Alfred in Philadelphia).[41] The Alfred flag has been credited to Margaret Manny.[42] It was used by the American Continental forces as a naval ensign and garrison flag in 1776 and early 1777. It is widely believed that the flag was raised by George Washington's army on New Year's Day 1776 at Prospect Hill in Charlestown (now part of Somerville), near his headquarters at Cambridge, Massachusetts, and that the flag was interpreted by British observers as a sign of surrender.[43] Some scholars dispute this traditional account, concluding that the flag raised at Prospect Hill was likely a British union flag.[44]

Place names

Alabama

- Birmingham after Birmingham, England

Connecticut

Delaware

- Dover after Dover, England

- Kent County, Delaware after Kent, England

- Wilmington named by Proprietor Thomas Penn after his friend Spencer Compton, Earl of Wilmington, who was prime minister in the reign of George II of Great Britain.

Maryland

- Aberdeen, Maryland after Aberdeen, Scotland

- Chester, Maryland after Chester, England

- Chestertown, Maryland after Chester, England

- Essex, Maryland after Essex, England

- Glencoe, Maryland after Glencoe, Scotland

- Hereford, Maryland after Hereford, England

- Manchester, Maryland after Manchester, England

- Westminster, Maryland after Westminster, England

Massachusetts

- Bedford, Massachusetts after Bedford, England

- Boston after Boston, England[45]

- Cambridge after the City of Cambridge, England[46]

- Falmouth, Massachusetts after Falmouth, England

- Gloucester after Gloucester, England

- Hampshire County, Massachusetts after Hampshire, England

- Middlesex County, Massachusetts after Middlesex, England

- Plymouth, Massachusetts after Plymouth, England

- Southampton after Southampton, England[47]

- Suffolk County, Massachusetts after Suffolk, England

- Swansea, Massachusetts after Swansea, Wales

- Weymouth, Massachusetts after Weymouth, Dorset, England

- Worcester, Massachusetts after Worcester, England

New Hampshire

- New Hampshire state (after Hampshire[48])

- Derry, New Hampshire after Derry, Northern Ireland

- Durham, New Hampshire after Durham, England

- Exeter, New Hampshire after Exeter, England

- Londonderry, New Hampshire after Londonderry, Northern Ireland

- Manchester after Manchester, England[49]

- New London, New Hampshire after London, England

- Plymouth, New Hampshire after Plymouth, England

- Portsmouth, New Hampshire after Portsmouth, England

Pennsylvania

- Bucks County after Buckinghamshire, England

- Chester County and Chester after Chester, England

- Carlisle, Pennsylvania after Carlisle, England

- Darby derived from Derby (pronounced "Darby"), the county town of Derbyshire (pronounced "Darbyshire")[50]

- Lancaster County and Lancaster after the city of Lancaster in the county of Lancashire in England, the native home of John Wright, one of the early settlers.[51]

- Reading, Berks County after Reading, Berkshire, England

- Warminster after a small town in the county of Wiltshire, at the western extremity of Salisbury Plain, England.[52]

- York, Pennsylvania after York, England

Virginia

- Crewe, Virginia after Crewe, England

- Dumfries, Virginia after Dumfries, Scotland

- Edinburg, Virginia after Edinburgh, Scotland

- Falmouth, Virginia after Falmouth, England

- Isle of Wight County, Virginia after Isle of Wight, England

- Kilmarnock, Virginia after Kilmarnock, Scotland

- Glasgow, Virginia after Glasgow, Scotland

- Gloucester, Virginia after Gloucester, England

- Richmond, Virginia and Richmond County, Virginia after Richmond, London

- Lancaster County, Virginia after Lancashire, England

- Midlothian, Virginia after Midlothian, Scotland

- New Kent County, Virginia after Kent County, England

- Norfolk, Virginia after Norfolk, England

- Northampton County, Virginia after Northampton, England

- Northumberland County, Virginia after Northumberland, England

- Portsmouth, Virginia after Portsmouth, England

- Stafford, Virginia after Stafford, England

- Suffolk, Virginia after Suffolk, England

- Westmoreland County, Virginia after Westmoreland (now part of Cumbria, England

- Winchester, Virginia after Winchester, England

In addition, some places were named after the kings and queens of the former kingdoms of England and Ireland. The name Virginia was first applied by Queen Elizabeth I (the "Virgin Queen") and Sir Walter Raleigh in 1584.,[53] the Carolinas were named after King Charles I and Maryland named so for his wife, Queen Henrietta Maria (Queen Mary).[54]

See also

References

- ↑ Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Search". factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- 1 2 Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ "About Ancestry.co.uk". Ancestry.co.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Dominic J. Pulera. Sharing the Dream: White Males in a Multicultural America.

- ↑ Reynolds Farley, 'The New Census Question about Ancestry: What Did It Tell Us?', Demography, Vol. 28, No. 3 (August 1991), pp. 414, 421.

- ↑ Stanley Lieberson and Lawrence Santi, 'The Use of Nativity Data to Estimate Ethnic Characteristics and Patterns', Social Science Research, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1985), pp. 44-6.

- ↑ Stanley Lieberson and Mary C. Waters, 'Ethnic Groups in Flux: The Changing Ethnic Responses of American Whites', Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 487, No. 79 (September 1986), pp. 82-86.

- ↑ Mary C. Waters, Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), p. 36.

- ↑ "Genealogy Data: Frequently Occurring Surnames from Census 2000 - U.S. Census Bureau". Census.gov. 21 December 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ "Persons Who Reported at Least One Specific Ancestry Group for the United States: 1980" (PDF). Census.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ "Rank of States for Selected Ancestry Groups with 100,00 or more persons: 1980" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ "1990 Census of Population Detailed Ancestry Groups for States" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 18 September 1992. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ "Ancestry: 2000". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ Stanley Lieberson, Mary C. Waters. From many strands: ethnic and racial groups in contemporary América.

- ↑ Historical U.S. population by race Archived 2010-02-25 at WebCite

- ↑ Ethnicity in Contemporary America. Books.google.com. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ↑ "United States 1980 Census" (PDF). Census.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ "United States 1990 Census" (PDF). Census.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ "Ancestry: 2000" (PDF). United States Government. June 2004.

- ↑ Samuel Peter Orth. Our Foreigners: A Chronicle of Americans in the Making.

- ↑ Szucs, Loretto Dennis; Luebking, Sandra Hargreaves (2006). The Source. Books.google.com. ISBN 9781593312770. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. 1790 Census" (PDF). Census.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ "Scottish Ancestry Search - Scottish Genealogy by City". Epodunk.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ "Top 101 cities with the most residents of English ancestry (population 500+)". Epodunk.com. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ↑ "Welsh Ancestry Search - Welsh Genealogy by City". Epodunk.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ Almost All Aliens: Immigration, Race, and Colonialism in American History ... By Paul Spickard

- ↑ Statistical Abstract of the United States (Page: 89)

- ↑ Statistical Abstract of the United States Immigration by country of origin 1851-1940 (Page: 107)

- ↑ Statistical Abstract of the United States (Page: 92)

- ↑ "Brits Abroad". BBC News. 2006-12-06. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ↑ Sriskandarajah, Dhananjayan; Drew, Catherine (December 11, 2006). "Brits Abroad: Mapping the scale and nature of British emigration". IPPR. Archived from the original on 2008-05-24. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- 1 2 3 Ember et al 2004, p. 47.

- 1 2 Marshall 2001, p. 254.

- 1 2 Ember et al 2004, p. 48.

- ↑ Ember et al 2004, p. 49.

- 1 2 Henretta, James A. (2007), "History of Colonial America", Encarta Online Encyclopedia, archived from the original on 2009-10-31

- ↑ "Chapter 3: The Road to Independence", Outline of U.S. History, usinfo.state.gov, November 2005, archived from the original on April 9, 2008, retrieved 2008-04-21

- ↑ James, Wither (March 2006), "An Endangered Partnership: The Anglo-American Defence Relationship in the Early Twenty-first Century", European Security, 15 (1): 47–65, doi:10.1080/09662830600776694, ISSN 0966-2839

- ↑ Colley 1992, p. 134.

- ↑ "Letters of delegates to Congress, 1774-1789, Volume 2, September 1775-December 1775". virginia.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-01-12.

- ↑ Leepson, 51

- ↑ Preble (1880) p. 218

- ↑ Ansoff (2006)

- ↑ "A Tale of Two Bostons - iBoston". Iboston.org. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ Cambridge, City of. "Brief History of Cambridge, Mass. - Cambridge Historical Commission - City of Cambridge, Massachusetts". Cambridgema.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ "ePodunk". Epodunk.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ http://www.n-state.com, NSTATE, LLC:. "The State of New Hampshire - An Introduction to the Granite State from NETSTATE.COM". Netstate.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ "New Hampshire". Boulter.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 100.

- ↑ Petition for the Establishment of Lancaster County Archived 2006-08-07 at the Wayback Machine., February 6, 1728/9

- ↑ "WARMINSTER TOWNSHIP HISTORY". Warminstertownship.org. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ↑ In 1584 Sir Walter Raleigh sent Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to lead an exploration of what is now the North Carolina coast, and they returned with word of a regional "king" named "Wingina." This was modified later that year by Raleigh and the Queen to "Virginia", perhaps in part noting her status as the "Virgin Queen." Stewart, George (1945). Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States. New York: Random House. p. 22.

- ↑ "The State of Maryland". netstate.com.

Scholarly sources

- Oscar Handlin, Ann Orlov and Stephan Thernstrom eds. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1980) the standard reference source for all ethnic groups.

- Rowland Tappan Berthoff. British Immigrants in Industrial America, 1790-1950 (1953).

- David Hackett Fischer. Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways In America (1989).