Acts of Union 1707

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png) | |

| Long title | An Act for a Union of the Two Kingdoms of England and Scotland |

|---|---|

| Citation | 1706 c. 11 |

| Territorial extent | Kingdom of England (inc. Wales); subsequently, United Kingdom |

Status: Current legislation | |

| Revised text of statute as amended | |

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png) | |

| Long title | Act Ratifying and Approving the Treaty of Union of the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England |

|---|---|

| Citation | 1707 c. 7 |

| Territorial extent | Kingdom of Scotland; subsequently, United Kingdom |

Status: Current legislation | |

| Revised text of statute as amended | |

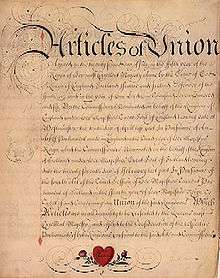

The Acts of Union were two Acts of Parliament: the Union with Scotland Act 1706 passed by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act passed in 1707 by the Parliament of Scotland. They put into effect the terms of the Treaty of Union that had been agreed on 22 July 1706, following negotiation between commissioners representing the parliaments of the two countries. By the two Acts, the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland—which at the time were separate states with separate legislatures, but with the same monarch—were, in the words of the Treaty, "United into One Kingdom by the Name of Great Britain".[2]

The two countries had shared a monarch since the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when King James VI of Scotland inherited the English throne from his double first cousin twice removed, Queen Elizabeth I. Although described as a Union of Crowns, until 1707 there were in fact two separate Crowns resting on the same head (as opposed to the implied creation of a single Crown and a single Kingdom, exemplified by the later Kingdom of Great Britain). There had been three attempts in 1606, 1667, and 1689 to unite the two countries by Acts of Parliament, but it was not until the early 18th century that both political establishments came to support the idea, albeit for different reasons.

The Acts took effect on 1 May 1707. On this date, the Scottish Parliament and the English Parliament united to form the Parliament of Great Britain, based in the Palace of Westminster in London, the home of the English Parliament.[3] Hence, the Acts are referred to as the Union of the Parliaments. On the Union, the historian Simon Schama said "What began as a hostile merger, would end in a full partnership in the most powerful going concern in the world ... it was one of the most astonishing transformations in European history."[4]

Historical background

.svg.png)

Pre-1707 attempts at Union

Despite attempts by Edward I to conquer Scotland in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, the two countries were entirely separate. However, when Elizabeth I became Queen of England in 1558, a union became increasingly likely as she neither married or had children. From 1558 onwards, her heir was her Catholic cousin Mary, Queen of Scots who pledged herself to a peaceful union between the two kingdoms.[5] In 1567, Mary was forced to abdicate as Queen of Scots and replaced by her infant son James VI and I, who was brought up as a Protestant and became heir to the English throne. After Elizabeth died in 1603, the two Crowns were held in personal union by James and his Stuart successors but England and Scotland remained separate entities.

1603-1639

When James became King of England in 1603, the creation of a unified Church of Scotland and England governed by bishops was the first step in his vision of a centralised, Unionist state.[6] On his accession, he announced his intention to unite the two realms so he would not be "guilty of bigamy;" he used the royal prerogative to take the title "King of Great Britain"[7] and give a British character to his court and person.[8]

The 1603 Union of England and Scotland Act established a joint Commission to agree terms but the English Parliament was concerned this would lead to the imposition of an absolutist structure similar to that of Scotland.[9] James dropped his policy of a speedy union, the topic disappeared from the legislative agenda while attempts to revive it in 1610 were met with hostility.[10]

This did not mean James abandoned the idea; 17th century religion and politics were closely linked and he viewed a unified Church of Scotland and England as the first step towards a centralised, Unionist state.[11] The problem was that the two churches were very different in both structure and doctrine; Scottish bishops presided over Presbyterian structures but were doctrinal Calvinists who viewed many Church of England practices as little better than Catholicism.[12] The religious policies followed by James and his son Charles I were intended as precursors to political union; resistance to this concept led to the 1638 National Covenant in Scotland and the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

1639-1670

The 1639-1640 Bishops' Wars confirmed the primacy of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland or kirk and established a Covenanter government in Scotland. The Scots remained neutral when the First English Civil War began in 1642, but grew concerned as to the impact of Royalist victory on Scotland after Parliamentary defeats in the first year of the war.[13] Religious union with England was also seen as the best way to preserve a Presbyterian kirk.[14] The 1643 Solemn League and Covenant provided Scottish military support for the English Parliament in return for a religious union between the Church of England and the kirk. While it referred repeatedly to 'union' between England, Scotland, and Ireland, it did not explicitly commit to political union which had little support even among their English supporters.

Even religious union was fiercely opposed by the Episcopalian majority in the Church of England and Independents like Oliver Cromwell. The Scots and English Presbyterians came to see the Independents who dominated the New Model Army as a bigger threat than the Royalists and when Charles I surrendered in 1646, they agreed to restore him to the English throne. Both Royalists and Covenanters agreed the institution of monarchy was divinely ordered but disagreed on the nature and extent of Royal authority versus that of the church.[15]

After defeat in the 1647-1648 Second English Civil War, Scotland was occupied by English troops which were withdrawn once the so-called Engagers whom Cromwell held responsible for the war had been replaced by the Kirk Party. In December 1648, Pride's Purge confirmed Cromwell's political control in England by removing Presbyterian MPs from Parliament and executing Charles in January 1649. Despite this, in February, the Kirk Party proclaimed Charles II King of Scotland and Great Britain; and agreed to restore him to the English throne.

Defeat in the 1649-1651 Third English Civil War or Anglo-Scottish War resulted in Scotland's incorporation into the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, largely driven by Cromwell's determination to break the power of the kirk, which he held responsible for the Anglo-Scottish War.[16] The 1652 Tender of Union was followed on 12 April 1654 by An Ordinance by the Protector for the Union of England and Scotland, creating the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland.[17] It was ratified by the Second Protectorate Parliament on 26 June 1657, creating a single Parliament in Westminster, with 30 representatives each from Scotland and Ireland added to the existing English members.[18]

While it established free trade within the Commonwealth, the economic benefits were diminished by the heavy taxation needed to fund the army.[19] In Scotland, Union was associated with military occupation, in England with heavy taxes and had little popular support in either country. It was dissolved by the 1660 Restoration of Charles II despite a petition by Scottish members of the Commonwealth Parliament for its continuance.

The Scottish economy was badly damaged by the English Navigation Acts of 1660 and 1663 and wars with the Dutch Republic, its major export market. An Anglo-Scots Trade Commission was set up in January 1668 but the English had no interest in making concessions, as the Scots had little to offer in return. In 1669, Charles II revived talks on political union; his motives were to weaken Scotland's commercial and political links with the Dutch, still seen as an enemy and complete the work of his grandfather James I.[20] Continued opposition in both England and Scotland meant that by the end of 1669, negotiations between Commissioners ground to a halt.[21]

1670-1707

Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, a Scottish Convention met in Edinburgh in April 1689 to agree a new constitutional settlement; during which the Scottish Bishops backed a proposed union in an attempt to preserve Episcopalian control of the kirk. William and Mary were supportive of the idea but it was opposed both by the Presbyterian majority in Scotland and the English Parliament.[22] Episcopacy in Scotland was abolished in 1690, alienating a significant part of the political class; it was this element that later formed the bedrock of opposition to Union.[23]

The 1690s were a time of economic hardship in Europe as a whole and Scotland in particular, a period now known as the Seven ill years which led to strained relations with England.[24] In 1698, the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies received a charter to raise capital through public subscription.[25] The Company invested in the Darién scheme, an ambitious plan funded almost entirely by Scottish investors to build a colony on the Isthmus of Panama for trade with East Asia.[26] The scheme was a disaster; the losses of over £150,000 severely impacted the Scottish commercial system.[27] The financial losses incurred have often been suggested as one of the drivers behind Union.

Treaty and passage of the Acts of 1707

Deeper political integration had been a key policy of Queen Anne from the time she acceded to the throne in 1702. Under the aegis of the Queen and her ministers in both kingdoms, the parliaments of England and Scotland agreed to participate in fresh negotiations for a union treaty in 1705.

Both countries appointed 31 commissioners to conduct the negotiations. Most of the Scottish commissioners favoured union, and about half were government ministers and other officials. At the head of the list was Queensberry, and the Lord Chancellor of Scotland, the Earl of Seafield.[28] The English commissioners included the Lord High Treasurer, the Earl of Godolphin, the Lord Keeper, Baron Cowper, and a large number of Whigs who supported union. Tories were not in favour of union and only one was represented among the commissioners.[28]

Negotiations between the English and Scottish commissioners took place between 16 April and 22 July 1706 at the Cockpit in London. Each side had its own particular concerns. Within a few days, England gained a guarantee that the Hanoverian dynasty would succeed Queen Anne to the Scottish crown, and Scotland received a guarantee of access to colonial markets, in the hope that they would be placed on an equal footing in terms of trade.[29]

After negotiations ended in July 1706, the acts had to be ratified by both Parliaments. In Scotland, about 100 of the 227 members of the Parliament of Scotland were supportive of the Court Party. For extra votes the pro-court side could rely on about 25 members of the Squadrone Volante, led by the Marquess of Montrose and the Duke of Roxburghe. Opponents of the court were generally known as the Country party, and included various factions and individuals such as the Duke of Hamilton, Lord Belhaven and Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, who spoke forcefully and passionately against the union. The Court party enjoyed significant funding from England and the Treasury and included many who had accumulated debts following the Darien Disaster.[30]

In Scotland, the Duke of Queensberry was largely responsible for the successful passage of the Union act by the Scottish Parliament. In Scotland, he received much criticism from local residents, but in England he was cheered for his action. He had received around half of the funding awarded by the Westminster treasury for himself. In April 1707, he travelled to London to attend celebrations at the royal court, and was greeted by groups of noblemen and gentry lined along the road. From Barnet, the route was lined with crowds of cheering people, and once he reached London a huge crowd had formed. On 17 April, the Duke was gratefully received by the Queen at Kensington Palace.[31]

Political motivations

The Acts of Union should be seen within a wider European context of increasing state centralisation during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. This included the monarchies of France, Sweden, Denmark and Spain. While there were exceptions such as the Dutch Republic or the Republic of Venice, the trend was clear.[32]

The dangers of the monarch using one Parliament against the other became apparent in the wars of 1647 and 1651 and resurfaced during the Exclusion Crisis. English resistance to the Catholic James succeeding his brother Charles resulted in him being sent to Edinburgh in 1681 as Lord High Commissioner. In August, the Scottish Parliament passed the Succession Act, confirming the divine right of kings, the rights of the natural heir 'regardless of religion,' the duty of all to swear allegiance to that king and the independence of the Scottish Crown. It then went beyond ensuring James's succession to the Scottish throne by explicitly stating the aim was to make his exclusion from the English throne impossible without '...the fatall and dreadfull consequences of a civil war.'[33]

The issue reappeared during the 1688 Glorious Revolution. Contrary to what is often assumed, the English Parliament generally supported the replacement of James with his Protestant daughter Mary II but strongly resisted making her Dutch husband William III & II joint ruler. They only gave way when he threatened to return to the Netherlands and Mary refused to rule without him.[34]

In Scotland, conflict over control of the kirk between Presbyterians and Episcopalians and William's position as a fellow Calvinist put him in a much stronger position. Originally, William insisted on retaining Episcopacy in the kirk and the Committee of the Articles, an unelected body that controlled what legislation Parliament could debate. Both of these would have given the Crown far greater control than in England but he withdrew his demands due to the 1689-1692 Jacobite Rising.[35]

English perspective

The English purpose was to ensure that Scotland would not choose a monarch different from the one on the English throne. The two countries had shared a king for much of the previous century, but the English were concerned that an independent Scotland with a different king, even if he were a Protestant, might make alliances against England. The English succession was provided for by the English Act of Settlement 1701, which ensured that the monarch of England would be a Protestant member of the House of Hanover. Until the Union of Parliaments, the Scottish throne might be inherited by a different successor after Queen Anne: the Scottish Act of Security 1704 granted parliament the right to choose a successor and explicitly required a choice different from the English monarch unless the English were to grant free trade and navigation. Many people in England were unhappy about the prospect, however. English overseas possessions made England very wealthy in comparison to Scotland, a poor country with few roads, very little industry and almost no Navy. This made some view unification as a markedly unequal relationship.

Scottish perspective

In Scotland, some claimed that union would enable Scotland to recover from the financial disaster wrought by the Darien scheme through English assistance and the lifting of measures put in place through the Alien Act to force the Scottish Parliament into compliance with the Act of Settlement.[36]

The combined votes of the Court party with a majority of the Squadrone Volante were sufficient to ensure the final passage of the treaty through the House.

Personal financial interests were also allegedly involved. Many Commissioners had invested heavily in the Darien scheme and they believed that they would receive compensation for their losses; Article 15 granted £398,085 10s sterling to Scotland, a sum known as The Equivalent, to offset future liability towards the English national debt. In essence it was also used as a means of compensation for investors in the Company of Scotland's Darien scheme, as 58.6% was allocated to its shareholders and creditors.[37]

Even more direct bribery was also said to be a factor.[38] £20,000 (£240,000 Scots) was dispatched to Scotland for distribution by the Earl of Glasgow. James Douglas, 2nd Duke of Queensberry, the Queen's Commissioner in Parliament, received £12,325, more than 60% of the funding. Robert Burns referred to this:

We're bought and sold for English Gold,

Such a Parcel of Rogues in a Nation.

Some of the money was used to hire spies, such as Daniel Defoe; his first reports were of vivid descriptions of violent demonstrations against the Union. "A Scots rabble is the worst of its kind," he reported, "for every Scot in favour there is 99 against". Years later, Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, originally a leading Unionist, wrote in his memoirs that Defoe "was a spy among us, but not known as such, otherwise the Mob of Edinburgh would pull him to pieces."

The Treaty could be considered very unpopular at the time. Popular unrest occurred in Edinburgh, as mentioned above, with some lesser but still substantial riots in Glasgow. The people of Edinburgh demonstrated against the treaty, and their apparent leader in opposition to the Unionists was James Hamilton, 4th Duke of Hamilton. However, Hamilton was actually on the side of the English Government. Demonstrators in Edinburgh were opposed to the Union for many reasons: they feared the Kirk would be Anglicised; that Anglicisation would remove democracy from the only really elementally democratic part of the Kingdom; and they feared that tax rises would come.[39]

Sir George Lockhart of Carnwath, the only member of the Scottish negotiating team against union, noted that "The whole nation appears against the Union"[40] and even Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, an ardent pro-unionist and Union negotiator, observed that the treaty was "contrary to the inclinations of at least three-fourths of the Kingdom".[40] Public opinion against the Treaty as it passed through the Scottish Parliament was voiced through petitions from shires, burghs, presbyteries and parishes. The Convention of Royal Burghs also petitioned against the Union as proposed:

That it is our indispensable duty to signify to your grace that, as we are not against an honourable and safe union with England far less can we expect to have the condition of the people of Scotland, with relation to these great concerns, made better and improved without a Scots Parliament.[41]

Not one petition in favour of an incorporating union was received by Parliament. On the day the treaty was signed, the carilloner in St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, rang the bells in the tune Why should I be so sad on my wedding day?[42] Threats of widespread civil unrest resulted in Parliament imposing martial law.

Provisions of the Acts

The Treaty of Union, agreed between representatives of the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland in 1706, consisted of 25 articles, 15 of which were economic in nature. In Scotland, each article was voted on separately and several clauses in articles were delegated to specialised subcommittees. Article 1 of the treaty was based on the political principle of an incorporating union and this was secured by a majority of 116 votes to 83 on 4 November 1706. To minimise the opposition of the Church of Scotland, an Act was also passed to secure the Presbyterian establishment of the Church, after which the Church stopped its open opposition, although hostility remained at lower levels of the clergy. The treaty as a whole was finally ratified on 16 January 1707 by a majority of 110 votes to 69.[43]

The two Acts incorporated provisions for Scotland to send representative peers from the Peerage of Scotland to sit in the House of Lords. It guaranteed that the Church of Scotland would remain the established church in Scotland, that the Court of Session would "remain in all time coming within Scotland", and that Scots law would "remain in the same force as before". Other provisions included the restatement of the Act of Settlement 1701 and the ban on Roman Catholics from taking the throne. It also created a customs union and monetary union.

The Act provided that any "laws and statutes" that were "contrary to or inconsistent with the terms" of the Act would "cease and become void".

Related Acts

The Scottish Parliament also passed the Protestant Religion and Presbyterian Church Act 1707 guaranteeing the status of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. The English Parliament passed a similar Act, 6 Anne c.8.

Soon after the Union, the Act 6 Anne c.40—later named the Union with Scotland (Amendment) Act 1707—united the English and Scottish Privy Councils and decentralised Scottish administration by appointing justices of the peace in each shire to carry out administration. In effect it took the day-to-day government of Scotland out of the hands of politicians and into those of the College of Justice.

In the year following the Union, the Treason Act 1708 abolished the Scottish law of treason and extended the corresponding English law across Great Britain.

Evaluations

Scotland benefited, says historian G.N. Clark, gaining "freedom of trade with England and the colonies" as well as "a great expansion of markets". The agreement guaranteed the permanent status of the Presbyterian church in Scotland, and the separate system of laws and courts in Scotland. Clark argued that in exchange for the financial benefits and bribes that England bestowed, what it gained was

of inestimable value. Scotland accepted the Hanoverian succession and gave up her power of threatening England's military security and complicating her commercial relations ... The sweeping successes of the eighteenth-century wars owed much to the new unity of the two nations.[44]

By the time Samuel Johnson and James Boswell made their tour in 1773, recorded in A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland, Johnson noted that Scotland was "a nation of which the commerce is hourly extending, and the wealth increasing" and in particular that Glasgow had become one of the greatest cities of Britain.[45]

300th anniversary

A commemorative two-pound coin was issued to mark the tercentennial—300th anniversary—of the Union, which occurred two days before the Scottish Parliament general election on 3 May 2007.[46]

The Scottish Executive held a number of commemorative events through the year including an education project led by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, an exhibition of Union-related objects and documents at the National Museums of Scotland and an exhibition of portraits of people associated with the Union at the National Galleries of Scotland.[47]

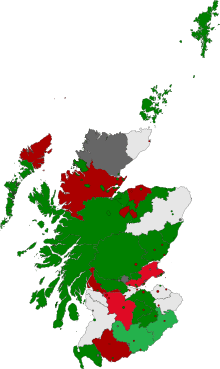

Scottish voting records

See also

Notes

- ↑ The citation of this Act by this short title was authorised by section 1 of, and Schedule 1 to, the Short Titles Act 1896. Due to the repeal of those provisions, it is now authorised by section 19(2) of the Interpretation Act 1978.

- ↑ Article I of the Treaty of Union

- ↑ Act of Union 1707, Article 3

- ↑ Simon Schama (presenter) (22 May 2001). "Britannia Incorporated". A History of Britain. Episode 10. 3 minutes in. BBC One.

- ↑ ABDN.ac.uk

- ↑ Stephen, Jeffrey (January 2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special): 55–58.

- ↑ Larkin, James F.; Hughes, Paul L., eds. (1973). Stuart Royal Proclamations: Volume I. Clarendon Press. p. 19.

- ↑ Lockyer, R. (1998). James VI and I. London: Addison Wesley Longman. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-582-27962-3.

- ↑ Lockyer, op. cit., pp. 54–59

- ↑ Lockyer, op. cit., p.59

- ↑ Stephen, Jeffrey (January 2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special): 55–58.

- ↑ McDonald, Alan (1998). The Jacobean Kirk, 1567–1625: Sovereignty, Polity and Liturgy. Routledge. pp. 75–76. ISBN 185928373X.

- ↑ Kaplan, Lawrence (May 1970). "Steps to War: The Scots and Parliament, 1642-1643". ournal of British Studies. 9 (2): 50–70.

- ↑ Robertson, Barry (2014). Royalists at War in Scotland and Ireland, 1638–1650. Routledge. p. 125. ISBN 978-1317061069.

- ↑ Harris, Tim (2015). Rebellion: Britain's First Stuart Kings, 1567-1642. OUP Oxford. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0198743114.

- ↑ Morrill, John (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman. p. 162. ISBN 0582016754.

- ↑ Constitution.org

- ↑ The 1657 Act's long title was An Act and Declaration touching several Acts and Ordinances made since 20 April 1653, and before 3 September 1654, and other Acts

- ↑ Parliament.uk Archived 12 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ MacIntosh, Gillian (2007). Scottish Parliament under Charles II, 1660-1685. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 79-87 passim. ISBN 0748624570.

- ↑ C. Whatley, op. cit., p.95

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (1992). Scotland: a New History. Pimlico Publishing. p. 305. ISBN 0712698930.

- ↑ Harris, Tim (2007). Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685-1720. Penguin. pp. 404–406. ISBN 0141016523.

- ↑ Whatley, C. (2006). The Scots and the Union. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-7486-1685-3.

- ↑ Mitchison, Rosalind (2002). A History of Scotland (3rd ed.). Routledge. pp. 301–2. ISBN 0415278805.

- ↑ E. Richards, Britannia's Children: Emigration from England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland since 1600 (Continuum, 2004), ISBN 1852854413, p. 79.

- ↑ Mitchison, Rosalind (2002). A History of Scotland (3rd ed.). Routledge. p. 314. ISBN 0415278805.

- 1 2 "The commissioners". UK Parliament website. 2007. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "The course of negotiations". UK Parliament website. 2007. Archived from the original on 21 July 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Ratification". UK parliament website. 2007. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "1 May 1707 – the Union comes into effect". UK Parliament website. 2007. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ Munck, Thomas (2005). Seventeenth-Century Europe: State, Conflict and Social Order in Europe 1598-1700. Palgrave. pp. 429–431. ISBN 1403936196.

- ↑ Jackson, Clare (2003). Restoration Scotland, 1660-1690: Royalist Politics, Religion and Ideas. Boydell Press. pp. 38–54. ISBN 0851159303.

- ↑ Horwitz, Henry (1986). Parliament, Policy and Politics in the Reign of William III. MUP. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0719006619.

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (1992). Scotland, A New History. Vintage. pp. 300–303. ISBN 0712698930.

- ↑ Whatley, C. A. (2001). Bought and sold for English Gold? Explaining the Union of 1707. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. p. 48. ISBN 1-86232-140-X.

- ↑ Watt, Douglas. The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the wealth of nations. Luath Press 2007.

- ↑ Parliament.uk Archived 25 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bambery, Chris (2014). A People's History of Scotland. Verso.

- 1 2 "Scottish Referendums". BBC. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ The Humble Address of the Commissioners to the General Convention of the Royal Burrows of this Ancient Kingdom Convened the Twenty-Ninth of October 1706, at Edinburgh

- ↑ Notes by John Purser to CD Scotland's Music, Facts about Edinburgh.

- ↑ Riley, P. J. W. (1969). "The Union of 1707 as an Episode in English Politics". The English Historical Review. 84 (332): 498–527 [pp. 523–524]. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxxiv.cccxxxii.498. JSTOR 562482.

- ↑ G.N. Clark, The Later Stuarts, 1660–1714 (2nd ed. 1956) pp 290–93.

- ↑ Gordon Brown (2014). My Scotland, Our Britain: A Future Worth Sharing. Simon & Schuster UK. p. 150.

- ↑ House of Lords – Written answers, 6 November 2006, TheyWorkForYou.com

- ↑ Announced by the Scottish Culture Minister, Patricia Ferguson, 9 November 2006

Further reading

- Bowie, Karin. Scottish Public Opinion and the Anglo-Scottish Union, 1699–1707 (Boydell Press, 2007).

- Brown, Stewart J. and Christopher A. Whatley, eds. The Union of 1707: New Dimensions (Edinburgh UP, 2008).

- Deschamps, Yannick. "Résistances écossaises à l'union de 1707: essai historiographique," Dix-huitième siècle (2012) No. 44 pp 601–20 DOI : 10.3917/dhs.044.0601; online—use built in translator in Chrome for English

- Ferguson, William. "The Making of the Treaty of Union of 1707" Scottish Historical Review 43, (1964), p. 89-110.

- Ferguson, William. Scotland's Relations with England: A Survey to 1707 (Edinburgh John Donald, 1977), pp. 180–277.

- Herman, Arthur. How the Scots Invented the Modern World. Three Rivers Press, 2001. ISBN 0-609-80999-7

- Riley, P. W. J. The Union of England and Scotland: A Study in Anglo-Scottish Politics of the Eighteenth Century (Manchester UP, 1978).

- Smout, T. C. "Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707. I. The Economic Background" Economic History Review (1964) 16:3, pp. 455–467.

- Stephen, Jeffrey. Scottish Presbyterians and the Act of Union 1707 (Edinburgh UP, 2007).

Other books

- Defoe, Daniel. A tour thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain, 1724–27

- Defoe, Daniel. The Letters of Daniel Defoe, GH Healey editor. Oxford: 1955.

- Fletcher, Andrew (Saltoun). An Account of a Conversation

- Lockhart, George, "The Lockhart Papers", 1702–1728

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Union with England Act and Union with Scotland Act – Full original text

- Treaty of Union and the Darien Experiment, University of Guelph, McLaughlin Library, Library and Archives Canada

- Text of the Union with Scotland Act 1706 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk

- Text of the Union with England Act 1707 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk

.svg.png)