Lancashire

| Lancashire | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| County | |||

The Red Rose of Lancaster is the county flower of Lancashire, and a common symbol for the county. | |||

| |||

|

Motto: "In Consilio Consilium" ("In Counsel is Wisdom") | |||

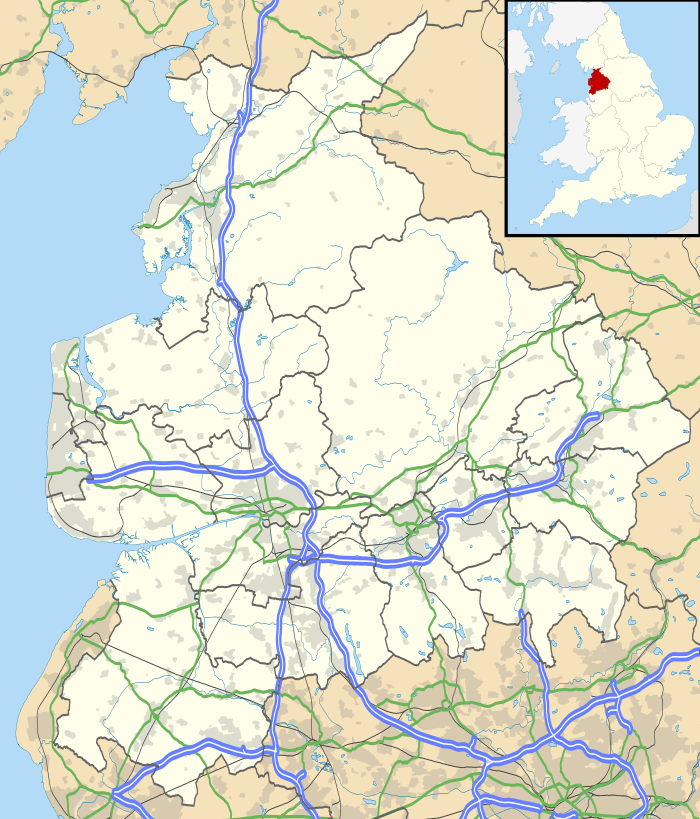

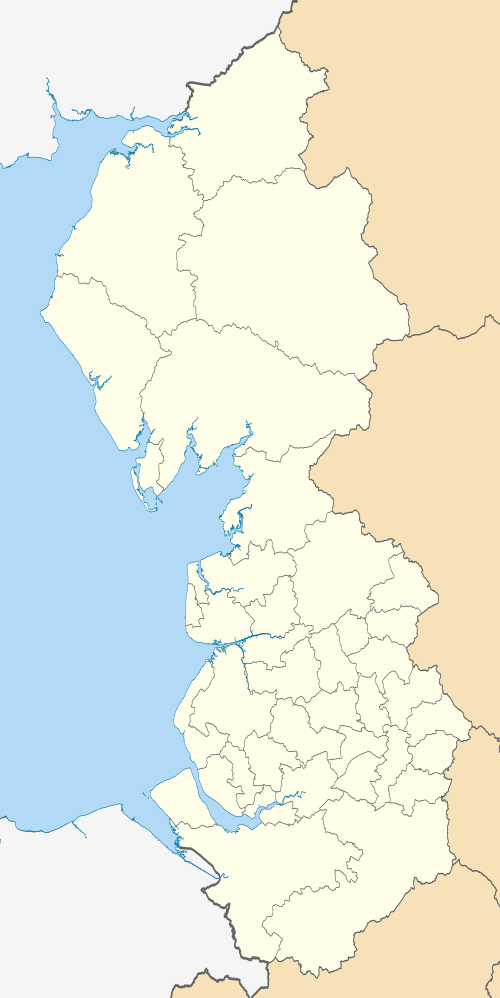

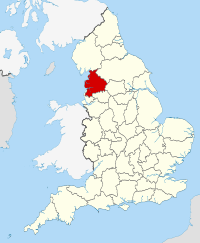

Lancashire in England | |||

| Sovereign state |

| ||

| Country |

| ||

| Region | North West England | ||

| Established | c. 1182[1] | ||

| Ceremonial county | |||

| Area | 3,079 km2 (1,189 sq mi) | ||

| • Ranked | 17th of 48 | ||

| Population (mid-2017 est.) | 1,490,500 | ||

| • Ranked | 8th of 48 | ||

| Density | 484/km2 (1,250/sq mi) | ||

| Ethnicity |

89.7% White British 6.0% S. Asian 2.1% Other White 0.9% Mixed 0.7% E. Asian and Other 0.5% Black 2005 Estimates | ||

| Non-metropolitan county | |||

| County council | Lancashire County Council | ||

| Executive | Conservative | ||

| Admin HQ | Preston | ||

| Area | 2,903 km2 (1,121 sq mi) | ||

| • Ranked | 16th of 27 | ||

| Population | 1,201,900 | ||

| • Ranked | 4th of 27 | ||

| Density | 413/km2 (1,070/sq mi) | ||

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-LAN | ||

| ONS code | 30 | ||

| NUTS | UKD43 | ||

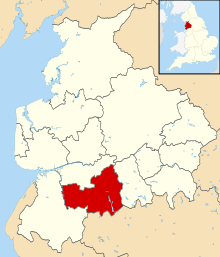

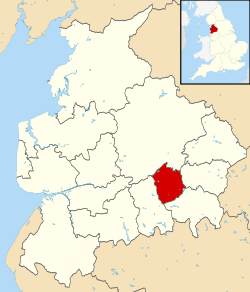

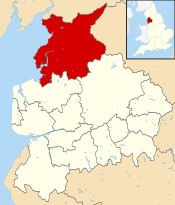

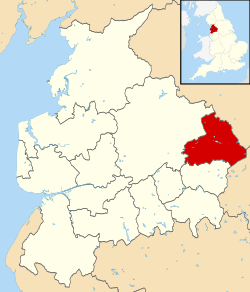

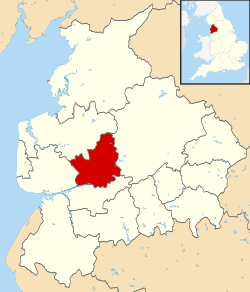

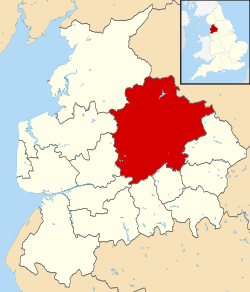

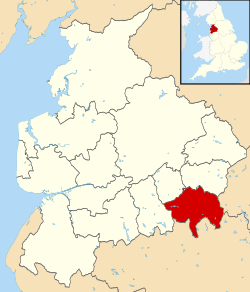

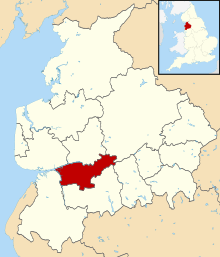

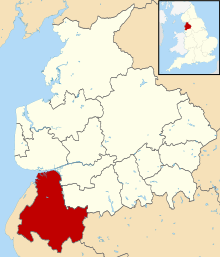

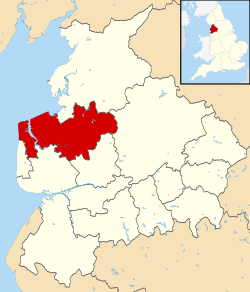

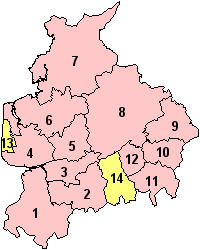

Districts of Lancashire | |||

| Districts | |||

| Members of Parliament | |||

| Time zone | Greenwich Mean Time (UTC) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | British Summer Time (UTC+1) | ||

Lancashire (/ˈlæŋkəʃər/ LANG-kə-shər, /-ʃɪər/ -sheer; abbreviated Lancs.) is a ceremonial county in north west England. The administrative centre is Preston. The county has a population of 1,449,300 and an area of 1,189 square miles (3,080 km2). People from Lancashire are known as Lancastrians.

The history of Lancashire begins with its founding in the 12th century. In the Domesday Book of 1086, some of its lands were treated as part of Yorkshire. The land that lay between the Ribble and Mersey, Inter Ripam et Mersam, was included in the returns for Cheshire. When its boundaries were established, it bordered Cumberland, Westmorland, Yorkshire, and Cheshire.

Lancashire emerged as a major commercial and industrial region during the Industrial Revolution. Liverpool and Manchester grew into its largest cities, dominating global trade and the birth of modern industrial capitalism. The county contained several mill towns and the collieries of the Lancashire Coalfield. By the 1830s, approximately 85% of all cotton manufactured worldwide was processed in Lancashire.[2] Accrington, Blackburn, Bolton, Burnley, Bury, Chorley, Colne, Darwen, Manchester, Nelson, Oldham, Preston, Rochdale and Wigan were major cotton mill towns during this time. Blackpool was a centre for tourism for the inhabitants of Lancashire's mill towns, particularly during wakes week.

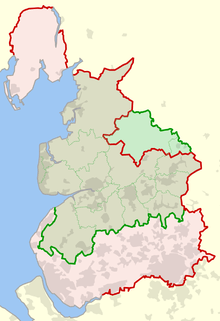

The historic county was subject to a significant boundary reform in 1974 which created the current ceremonial county and removed Liverpool and Manchester, and most of their surrounding conurbations to form the metropolitan and ceremonial counties of Merseyside and Greater Manchester.[3][4] The detached northern part of Lancashire in the Lake District, including the Furness Peninsula and Cartmel, was merged with Cumberland and Westmorland to form Cumbria. Lancashire lost 709 square miles of land to other counties, about two fifths of its original area, although it did gain some land from the West Riding of Yorkshire.

Today the ceremonial county borders Cumbria to the north, Greater Manchester and Merseyside to the south, and North and West Yorkshire to the east; with a coastline on the Irish Sea to the west. The county palatine boundaries remain the same as those of the pre-1974 county with Lancaster serving as the county town, and the Duke of Lancaster exercising sovereignty rights,[5] including the appointment of lords lieutenant in Greater Manchester and Merseyside.[6].

History

Early history

The county was established in 1182,[3] later than many other counties. During Roman times the area was part of the Brigantes tribal area in the military zone of Roman Britain. The towns of Manchester, Lancaster, Ribchester, Burrow, Elslack and Castleshaw grew around Roman forts. In the centuries after the Roman withdrawal in 410AD the northern parts of the county probably formed part of the Brythonic kingdom of Rheged, a successor entity to the Brigantes tribe. During the mid-8th century, the area was incorporated into the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, which became a part of England in the 10th century.

In the Domesday Book, land between the Ribble and Mersey were known as "Inter Ripam et Mersam"[7][8] and included in the returns for Cheshire.[9] Although some historians consider this to mean south Lancashire was then part of Cheshire,[8][10] it is by no means certain.[note 1][11][note 2] It is also claimed that the territory to the north formed part of the West Riding of Yorkshire.[10] It bordered on Cumberland, Westmorland, Yorkshire, and Cheshire.

The county was divided into hundreds, Amounderness, Blackburn, Leyland, Lonsdale, Salford and West Derby.[12] Lonsdale was further partitioned into Lonsdale North, the detached part north of the sands of Morecambe Bay including Furness and Cartmel, and Lonsdale South.

Modern history

Lancashire is smaller than its historical extent following a major reform of local government.[13] In 1889, the administrative county of Lancashire was created, covering the historic county except for the county boroughs such as Blackburn, Burnley, Barrow-in-Furness, Preston, Wigan, Liverpool and Manchester.[14] The area served by the Lord-Lieutenant (termed now a ceremonial county) covered the entirety of the administrative county and the county boroughs, and was expanded whenever boroughs annexed areas in neighbouring counties such as Wythenshawe in Manchester south of the River Mersey and historically in Cheshire, and southern Warrington. It did not cover the western part of Todmorden, where the ancient border between Lancashire and Yorkshire passes through the middle of the town.

During the 20th century, the county became increasingly urbanised, particularly the southern part. To the existing county boroughs of Barrow-in-Furness, Blackburn, Bolton, Bootle, Burnley, Bury, Liverpool, Manchester, Oldham, Preston, Rochdale, Salford, St. Helens and Wigan were added Warrington (1900), Blackpool (1904) and Southport (1905). The county boroughs also had many boundary extensions. The borders around the Manchester area were particularly complicated, with narrow protrusions of the administrative county between the county boroughs – Lees urban district formed a detached part of the administrative county, between Oldham county borough and the West Riding of Yorkshire.[15]

By the census of 1971, the population of Lancashire and its county boroughs had reached 5,129,416, making it the most populous geographic county in the UK.[16] The administrative county was also the most populous of its type outside London, with a population of 2,280,359 in 1961. On 1 April 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972, the administrative county was abolished, as were the county boroughs. The urbanised southern part largely became part of two metropolitan counties, Merseyside and Greater Manchester.[17] The new county of Cumbria incorporates the Furness exclave.[3]

The boroughs of Liverpool, Knowsley, St. Helens and Sefton were included in Merseyside. In Greater Manchester the successor boroughs were Bury, Bolton, Manchester, Oldham (part), Rochdale, Salford, Tameside (part), Trafford (part) and Wigan. Warrington and Widnes, south of the new Merseyside/Greater Manchester border were added to the new non-metropolitan county of Cheshire. The urban districts of Barnoldswick and Earby, Bowland Rural District and the parishes of Bracewell and Brogden and Salterforth from Skipton Rural District in the West Riding of Yorkshire became part of the new Lancashire.[4] One parish, Simonswood, was transferred from the borough of Knowsley in Merseyside to the district of West Lancashire in 1994.[18] In 1998 Blackpool and Blackburn with Darwen became independent unitary authorities, removing them from the non-metropolitan county but not from the ceremonial county.

The Wars of the Roses tradition continued with Lancaster using the red rose symbol and York the white. Pressure groups, including Friends of Real Lancashire and the Association of British Counties advocate the use of the historical boundaries of Lancashire for ceremonial and cultural purposes.[19][20]

Geography

Divisions and environs

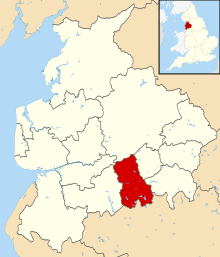

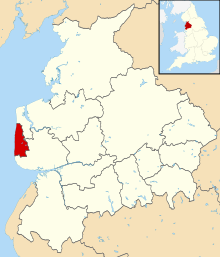

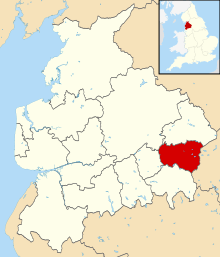

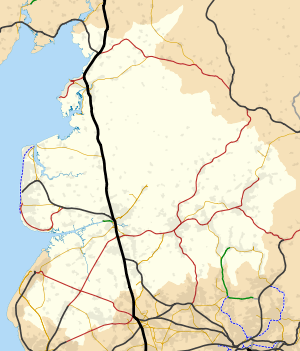

Lancashire, the shire county controlled by the county council is divided into local government districts, Burnley, Chorley, Fylde, Hyndburn, Lancaster, Pendle, Preston, Ribble Valley, Rossendale, South Ribble, West Lancashire, and Wyre.[21][22]

Blackpool and Blackburn with Darwen are unitary authorities that do not come under county council control.[23] The Lancashire Constabulary covers the shire county and the unitary authorities.[24] The ceremonial county, including the unitary authorities, borders Cumbria, North Yorkshire, West Yorkshire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside in the North West England region.[25]

Geology, landscape and ecology

The highest point of the county is Gragareth, near Whernside, which reaches a height of 627 m (2,057 ft).[26] Green Hill near Gragareth has also been cited as the county top.[27] The highest point within the historic boundaries is Coniston Old Man in the Lake District at 803 m (2,634 ft).[28]

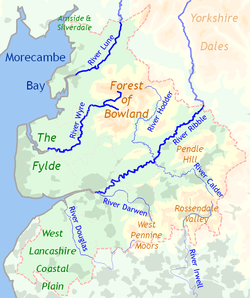

Lancashire rivers drain westwards from the Pennines into the Irish Sea. Rivers in Lancashire include the Ribble, Wyre and Lune. Their tributaries are the Calder, Darwen, Douglas, Hodder, and Yarrow. The Irwell has its source in Lancashire.

To the west of the county are the West Lancashire Coastal Plain and the Fylde coastal plain north of the Ribble Estuary. Further north is Morecambe Bay. Apart from the coastal resorts, these areas are largely rural with the land devoted to vegetable crops. In the northwest corner of the county, straddling the border with Cumbria, is the Arnside and Silverdale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), characterised by its limestone pavements and home to the Leighton Moss nature reserve.

To the east of the county are upland areas leading to the Pennines. North of the Ribble is Beacon Fell Country Park and the Forest of Bowland, another AONB. Much of the lowland in this area is devoted to dairy farming and cheesemaking, whereas the higher ground is more suitable for sheep, and the highest ground is uncultivated moorland. The valleys of the River Ribble and its tributary the Calder form a large gap to the west of the Pennines, overlooked by Pendle Hill. Most of the larger Lancashire towns are in these valleys South of the Ribble are the West Pennine Moors and the Forest of Rossendale where former cotton mill towns are in deep valleys. The Lancashire Coalfield, largely in modern-day Greater Manchester, extended into Merseyside and to Ormskirk, Chorley, Burnley and Colne in Lancashire.

Green belt

Lancashire contains green belt interspersed throughout the county, covering much of the southern districts and towns throughout the Ribble Valley, West Lancashire and The Fylde coastal plains to prevent convergence with the nearby Merseyside and Greater Manchester conurbations. Further pockets control the expansion of Lancaster, and surround the Blackpool urban area, as part of the western edge of the North West Green Belt. It was first drawn up from the 1950s. All the county's districts contain some portion of belt, the portion by Burnley also abutting the Forest of Pendle Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Politics

Parliamentary constituencies

| General Election 2017: Lancashire | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Labour | UKIP | Liberal Democrats | Green | Others | Turnout |

| 338,000 +59,000 |

362,000 +94,000 |

11,000 -90,000 |

28,000 −5,000 |

9,000 -9,000 |

2,000 −5,000 |

750,000 +40,000 |

| Overall Number of Seats as of 2017 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Labour | UKIP | Liberal Democrats | Green | Others |

| 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

County Council

Lancashire County Council is based in County Hall in Preston, It was built as a home for the county administration, the Quarter Sessions and Lancashire Constabulary) and opened on 14 September 1882.[29]

Local elections for 84 councillors from 84 divisions are held every four years. The council is currently No Overall Control with the Labour Party leading a minority administration.

| Election | Number of councillors elected by each political party | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Labour | Liberal Democrats | Independent | Green Party | BNP | UKIP | Idle Toad | |

| 2017 | 46 | 30 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1[30] | 0 |

| 2013 | 35 | 39 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2009 | 51 | 16 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2005 | 31 | 44 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2001 | 27 | 44 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Duchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is one of two royal duchies in England. It has landholdings throughout the region and elsewhere, operating as a property company, but also exercising the right of the Crown in the County Palatine of Lancaster.[5] While the administrative boundaries changed in the 1970s, the county palatine boundaries remain the same as the historic boundaries.[31] As a result, the High Sheriffs for Lancashire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside are appointed "within the Duchy and County Palatine of Lancaster".[32]

The High Sheriff is an ancient county officer, but is now a largely ceremonial post. High Shrievalties are the oldest secular titles under the Crown, in England and Wales. The High Sheriff is the representative of the monarch and is the "Keeper of The Queen's Peace" in the county, executing judgements of the High Court.[16]

The Duchy administers bona vacantia within the County Palatine, receiving the property of persons who die intestate and where the legal ownership cannot be ascertained. There is no separate Duke of Lancaster, the title merged into the Crown many centuries ago – but the Duchy is administered by the Queen in Right of the Duchy of Lancaster. A separate court system for the county palatine was abolished by Courts Act 1971. A particular form of The Loyal Toast, 'The Queen, Duke of Lancaster' is in regular use in the county palatine. Lancaster serves as the county town of the county palatine.

It is traditional that when giving the dinner toast to the Queen, in Lancashire only, that the form of words is to 'The Queen, the Duke of Lancaster'. This practice is still upheld within the county where after dinner toasts are made.

Economy

Lancashire in the 19th century was a major centre of economic activity, and hence one of wealth. Activities included coal mining, textile production, particularly cotton, and fishing. Preston Docks, an industrial port are now disused for commercial purposes. Lancashire was historically the location of the port of Liverpool while Barrow-in-Furness is famous for shipbuilding.

As of 2013, the largest private sector industry is the defence industry with BAE Systems Military Air Solutions division based in Warton on the Fylde coast. The division operates a manufacturing site in Samlesbury. Other defence firms include BAE Systems Global Combat Systems in Chorley, Ultra Electronics in Fulwood and Rolls-Royce plc in Barnoldswick.

The nuclear power industry has a plant at Springfields, Salwick operated by Westinghouse and Heysham nuclear power station is operated by British Energy. Other major manufacturing firms include Leyland Trucks, a subsidiary of Paccar building the DAF truck range.

Other companies with a major presence in Lancashire include:

- Airline Network, an internet travel company with headquarters in Preston.

- Baxi, a heating equipment manufacturer has a large manufacturing site in Bamber Bridge.

- Crown Paints, a major paint manufacturer based in Darwen.

- Enterprise plc, one of the UK's leading support services based in Leyland.

- Hanson plc, a building supplies company operates the Accrington brick works.

- Hollands Pies, a major manufacturer of baked goods based in Baxenden near Accrington.

- National Savings and Investments, the state-owned savings bank, which offers Premium Bonds and other savings products, has an office in Blackpool.

- Thwaites Brewery, a regional brewery founded in 1807 by Daniel Thwaites in Blackburn.

- Xchanging, a company providing business process outsourcing services, with operations in Fulwood.

- Fisherman's Friend, a confection company, famous for making strong mints and lozenges.

The Foulnaze cockle fishery is in Lytham. It has only opened the coastal cockle beds three times in twenty years; August 2013 was the last of these openings.[33]

Enterprise zone

The creation of Lancashire Enterprise Zone was announced in 2011. It was launched in April 2012, based at the airfields owned by BAE Systems in Warton and Samlesbury.[34] Warton Aerodrome covers 72 hectares (180 acres) and Samlesbury Aerodrome is 74 hectares.[35] Development is coordinated by Lancashire Enterprise Partnership, Lancashire County Council and BAE Systems.[34] The first businesses to move into the zone did so in March 2015, at Warton.[36]

In March 2015 the government announced a new enterprise zone would be created at Blackpool Airport, using some airport and adjoining land.[37] Operations at the airport will not be affected.[38]

Economic output

This is a chart of trend of regional gross value added of the non-metropolitan county of Lancashire at basic prices published by the Office for National Statistics with figures in millions of British pounds sterling.[39]

| Year | Regional Gross Value Added[note 3] | Agriculture[note 4] | Industry[note 5] | Services[note 6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 13,789 | 344 | 5,461 | 7,984 |

| 2000 | 16,584 | 259 | 6,097 | 10,229 |

| 2003 | 19,206 | 294 | 6,352 | 12,560 |

Education

Lancashire has a mostly comprehensive system with four state grammar schools. Not including sixth form colleges, there are 77 state schools (not including Burnley's new schools) and 24 independent schools. The Clitheroe area has secondary modern schools. Sixth form provision is limited at most schools in most districts, with only Fylde and Lancaster districts having mostly sixth forms at schools. The rest depend on FE colleges and sixth form colleges, where they exist. South Ribble has the largest school population and Fylde the smallest (only three schools). Burnley's schools have had a new broom and have essentially been knocked down and started again in 2006. There are many Church of England and Catholic faith schools in Lancashire.

Lancashire is home to four universities: Lancaster University, the University of Central Lancashire, Edge Hill University and the Lancaster campus of the University of Cumbria. Seven colleges offer higher education courses.

Transport

Road

The Lancashire economy relies strongly on the M6 motorway which runs from north to south, past Lancaster and Preston. The M55 connects Preston to Blackpool and is 11.5 miles (18.3 km) long. The M65 motorway from Colne, connects Burnley, Accrington, Blackburn to Preston. The M61 from Preston via Chorley and the M66 starting 500 metres (0.3 mi) inside the county boundary near Edenfield, provide links between Lancashire and Manchester] and the trans-Pennine M62. The M58 crosses the southernmost part of the county from the M6 near Wigan to Liverpool via Skelmersdale.

Other major roads include the east-west A59 between Liverpool in Merseyside and Skipton in North Yorkshire via Ormskirk, Preston and Clitheroe, and the connecting A565 to Southport; the A56 from Ramsbottom to Padiham via Haslingden and from Colne to Skipton; the A585 from Kirkham to Fleetwood; the A666 from the A59 north of Blackburn to Bolton via Darwen; and the A683 from Heysham to Kirkby Lonsdale via Lancaster.

Rail

The West Coast Main Line provides direct rail links with London and other major cities, with stations at Preston and Lancaster. East-west connections are carried via the East Lancashire Line between Blackpool and Colne via Lytham, Preston, Blackburn, Accrington and Burnley. The Ribble Valley Line runs from Bolton to Clitheroe via Darwen and Blackburn. There are connecting lines from Preston to Ormskirk and Bolton, and from Lancaster to Morecambe, Heysham and Skipton.

Air

Blackpool Airport are no longer operating domestic or international flights, but it is still the home of flying schools, private operators and North West Air Ambulance . Manchester Airport is the main airport in the region. Liverpool John Lennon Airport is nearby, while the closest airport to the Pendle Borough is Leeds Bradford.

There is an operational airfield at Warton near Preston where there is a major assembly and test facility for BAE Systems.

Ferry

Heysham offers ferry services to Ireland and the Isle of Man.[40] As part of its industrial past, Lancashire gave rise to an extensive network of canals, which extend into neighbouring counties. These include the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, Lancaster Canal, Sankey Canal, Bridgewater Canal, Rochdale Canal, Ashton Canal and Manchester Ship Canal.

Bus

Several bus companies run bus services in the Lancashire area serving the main towns and villages in the county with some services running to neighbouring areas, Cumbria, Greater Manchester, Merseyside and West Yorkshire.

Demography

The major settlements in the ceremonial county are concentrated on the Fylde coast (the Blackpool Urban Area), and a belt of towns running west-east along the M65: Preston, Blackburn, Accrington, Burnley, Nelson and Colne. South of Preston are the towns of Leyland and Chorley; the three formed part of the Central Lancashire New Town designated in 1970. The north of the county is predominantly rural and sparsely populated, except for the towns of Lancaster and Morecambe which form a large conurbation of almost 100,000 people. Lancashire is home to a significant Asian population, numbering over 70,000 and 6% of the county's population, and concentrated largely in the former cotton mill towns in the south east.

Population change

| Population totals for modern (post-1998) Lancashire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-1998 statistics were gathered from local government areas that now comprise Lancashire Source: Great Britain Historical GIS.[41] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Settlements

The table below has divided the settlements into their local authority district. Each district has a centre of administration; for some of these correlate with a district's largest town, while others are named after the geographical area.

Areas

- † – part of the West Riding of Yorkshire until 1974

- This table does not form an extensive list of the settlements in the ceremonial county. More settlements can be found at Category:Towns in Lancashire, Category:Villages in Lancashire, and Category:Civil parishes in Lancashire.

Historic areas

Some settlements which were historically part of the county now fall under the counties of West Yorkshire, Cheshire, Merseyside, Greater Manchester and Cumbria:[3][4][14][17][42][43][44]

Boundary changes to occur before 1974 include:[44]

- Todmorden (split between Lancashire and Yorkshire) entirely to West Riding of Yorkshire in 1889

- Mossley (split between Lancashire, Yorkshire and Cheshire) entirely to Lancashire in 1889

- Stalybridge, entirely to Cheshire in 1889

- the former county boroughs of Manchester and Warrington both extended south of the Mersey into historic Cheshire (areas such as Wythenshawe and Latchford)

- correspondingly, the former county borough of Stockport extended north into historic Lancashire, including areas such as Reddish and the Heatons (Heaton Chapel, Heaton Mersey, Heaton Moor and Heaton Norris).

Symbols

The Red Rose of Lancaster is the county flower found on the county's heraldic badge and flag. The rose was a symbol of the House of Lancaster, immortalised in the verse "In the battle for England's head/York was white, Lancaster red" (referring to the 15th-century Wars of the Roses). The traditional Lancashire flag, a red rose on a white field, was not officially registered. When an attempt was made to register it with the Flag Institute it was found that it was officially registered by Montrose in Scotland, several hundred years earlier with the Lyon Office. Lancashire's official flag is registered as a red rose on a gold field.

Sport

Cricket

Lancashire County Cricket Club has been one of the most successful county cricket teams, particularly in the one-day game. It is home to England cricket team members James Anderson and Jos Buttler. The County Ground, Old Trafford, Trafford has been the home cricket ground of LCCC since 1864.[45]

Historically important local cricket leagues include the Lancashire League, the Central Lancashire League and the North Lancashire and Cumbria League, all of which were formed in 1892. These league clubs hire international professional players to play alongside their amateur players.

Since 2000, the designated ECB Premier League[46] for Lancashire has been the Liverpool and District Cricket Competition.

Football

Football in Lancashire is governed by the Lancashire County Football Association which like most County Football Associations has boundaries which are aligned roughly with the historic counties. The Manchester Football Association and Liverpool County Football Association operate in Greater Manchester and Merseyside.[47][48]

Lancashire clubs were prominent in the formation of the Football League in 1888, with the league being officially named at a meeting in Manchester.[49][50] Of the twelve founder members of the league, six were from Lancashire: Accrington, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Burnley, Everton, and Preston North End.

The Football League now operates out of Preston.[51] The National Football Museum was founded at Deepdale, Preston in 2001, but moved to Manchester in 2012.[52]

Seven professional full-time teams were based in Lancashire, at the start of the 2018–2019 season:

- Premier League: Burnley

- Championship: Blackburn Rovers and Preston North End

- League One: Accrington Stanley, Blackpool and Fleetwood Town

- League Two: Morecambe

The county's most prominent football rivalries are the East Lancashire derby between Blackburn Rovers and Burnley, and the West Lancashire derby between Blackpool and Preston North End.

A further nine professional full-time teams lie within the historical borders of Lancashire but outside of the current ceremonial county. These include the Premier League clubs Everton, Liverpool, Manchester City and Manchester United.

Rugby League

Along with Yorkshire and Cumberland, Lancashire is recognised as the heartland of Rugby League. The county has produced many successful top flight clubs such as St. Helens, Wigan, Warrington and Widnes. The county was once the focal point for many of the sport's professional competitions including the Lancashire League competition which ran from 1895 to 1970, and the Lancashire County Cup which ran until 1993. Rugby League has also seen a representative fixture between Lancashire and Yorkshire contested 89 times since its inception in 1895.[53] In recent times there were several rugby league teams that are based within the ceremonial county which include Blackpool Panthers, East Lancashire Lions, Blackpool Sea Eagles, Bamber Bridge RLFC, Leyland Warriors, Chorley Panthers, Blackpool Stanley, Blackpool Scorpions and Adlington Rangers.

Archery

There are many archery clubs located within Lancashire.[54] In 2004 Lancashire took the winning title at the Inter-counties championships from Yorkshire who had held it for 7 years.[55]

Wrestling

Lancashire has a long history of wrestling, developing its own style called Lancashire wrestling, with many clubs that over the years have produced many renowned wrestlers. Some of these have crossed over into the mainstream world of professional wrestling, including Shak Khan, Billy Riley, Davey Boy Smith, William Regal, Wade Barrett and the Dynamite Kid.

Music

Folk music

Lancashire has a long and highly productive tradition of music making. In the early modern era the county shared in the national tradition of balladry, including perhaps the finest border ballad, "The Ballad of Chevy Chase", thought to have been composed by the Lancashire-born minstrel Richard Sheale.[56] The county was also a common location for folk songs, including "The Lancashire Miller", "Warrington Ale" and "The soldier's farewell to Manchester", while Liverpool, as a major seaport, was the subject of many sea shanties, including "The Leaving of Liverpool" and "Maggie May",[57] beside several local Wassailing songs.[56] In the Industrial Revolution changing social and economic patterns helped create new traditions and styles of folk song, often linked to migration and patterns of work.[58] These included processional dances, often associated with rushbearing or the Wakes Week festivities, and types of step dance, most famously clog dancing.[58][59]

A local pioneer of folk song collection in the first half of the 19th century was Shakespearean scholar James Orchard Halliwell,[60] but it was not until the second folk revival in the 20th century that the full range of song from the county, including industrial folk song, began to gain attention.[59] The county produced one of the major figures of the revival in Ewan MacColl, but also a local champion in Harry Boardman, who from 1965 onwards probably did more than anyone to popularise and record the folk song of the county.[61] Perhaps the most influential folk artists to emerge from the region in the late 20th century were Liverpool folk group The Spinners, and from Manchester folk troubadour Roy Harper and musician, comedian and broadcaster Mike Harding.[62][63][64] The region is home to numerous folk clubs, many of them catering to Irish and Scottish folk music. Regular folk festivals include the Fylde Folk Festival at Fleetwood.[65]

Classical music

Lancashire had a lively culture of choral and classical music, with very large numbers of local church choirs from the 17th century,[66] leading to the foundation of local choral societies from the mid-18th century, often particularly focused on performances of the music of Handel and his contemporaries.[67] It also played a major part in the development of brass bands which emerged in the county, particularly in the textile and coalfield areas, in the 19th century.[68] The first open competition for brass bands was held at Manchester in 1853, and continued annually until the 1980s.[69] The vibrant brass band culture of the area made an important contribution to the foundation and staffing of the Hallé Orchestra from 1857, the oldest extant professional orchestra in the United Kingdom.[70] The same local musical tradition produced eminent figures such as Sir William Walton (1902–88), son of an Oldham choirmaster and music teacher,[71] Sir Thomas Beecham (1879–1961), born in St. Helens, who began his career by conducting local orchestras[72] and Alan Rawsthorne (1905–71) born in Haslingden.[73] The conductor David Atherton, co-founder of the London Sinfonietta, was born in Blackpool in 1944.[74] Lancashire also produced more populist figures, such as early musical theatre composer Leslie Stuart (1863–1928), born in Southport, who began his musical career as organist of Salford Cathedral.[75]

More recent Lancashire-born composers include Hugh Wood (1932– Parbold),[76] Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (1934–2016, Salford),[77] Sir Harrison Birtwistle (1934–, Accrington),[78] Gordon Crosse (1937–, Bury),[79]John McCabe (1939–2015, Huyton),[80] Roger Smalley (1943–2015, Swinton), Nigel Osborne (1948–, Manchester), Steve Martland (1954–2013, Liverpool),[81] Simon Holt (1958–, Bolton)[82] and Philip Cashian (1963–, Manchester).[83] The Royal Manchester College of Music was founded in 1893 to provide a northern counterpart to the London musical colleges. It merged with the Northern College of Music (formed in 1920) to form the Royal Northern College of Music in 1972.[84]

Popular music

Liverpool produced a number of nationally and internationally successful popular singers in the 1950s, including traditional pop stars Frankie Vaughan and Lita Roza, and one of the most successful British rock and roll stars in Billy Fury.[62] Many Lancashire towns had vibrant skiffle scenes in the late 1950s, out of which by the early 1960s a flourishing culture of beat groups began to emerge, particularly around Liverpool and Manchester. It has been estimated that there were around 350 bands active in and around Liverpool in this era, often playing ballrooms, concert halls and clubs, among them the Beatles.[85] After their national success from 1962, a number of Liverpool performers were able to follow them into the charts, including Gerry & the Pacemakers, the Searchers and Cilla Black. The first act to break through in the UK who were not from Liverpool, or managed by Brian Epstein, were Freddie and the Dreamers, who were based in Manchester,[86] as were Herman's Hermits and the Hollies.[87] Led by the Beatles, beat groups from the region spearheaded the British Invasion of the US, which made a major contribution to the development of rock music.[88] After the decline of beat groups in the late 1960s the centre of rock culture shifted to London and there were relatively few local bands who achieved national prominence until the growth of a disco funk scene and the punk rock revolution in the mid and late 1970s.[89]

Cuisine

Lancashire is the origin of the Lancashire hotpot, a casserole dish traditionally made with lamb. Other traditional foods from the area include:

- Black peas, also known as parched peas: popular in Darwen, Bolton and Preston.

- Bury black pudding has long been associated with the county. The most notable brand, Chadwick's Original Bury Black Puddings, are still sold on Bury Market,[90] and are manufactured in Rossendale.

- Butter cake: slice of bread and butter.

- Butter pie: a savoury pie containing potatoes, onion and butter. Usually associated with Preston.

- Clapbread: a thin oatcake made from unleavened dough cooked on a griddle.

- Chorley cakes: from the town of Chorley.

- Eccles cakes are small, round cakes filled with currants and made from flaky pastry with butter, originally made in Eccles.

- Faggot: savoury duck

- Fag pie: pie made from chopped dried figs, sugar and lard. Associated with Blackburn and Burnley, where it was the highlight of Fag Pie Sunday (Mid-Lent Sunday).

- Fish and chips: first fish and chip shop in northern England opened in Mossley, near Oldham, around 1863.[91]

- Frog-i'-th'-'ole pudding: now known as "toad in the hole"

- Frumenty: sweet porridge. Once a popular dish at Lancashire festivals, such as Christmas and Easter Monday.

- Goosnargh cakes: small flat shortbread biscuits with coriander or caraway seeds pressed into the biscuit before baking.[92] Traditionally baked on feast days like Shrove Tuesday.

- Jannock: cake or small loaf of oatmeal. Allegedly introduced to Lancashire (possibly Bolton) by weavers of Flemish origin.

- Lancashire cheese has been made in the county for several centuries.[93] Beacon Fell Traditional Lancashire Cheese has been awarded EU Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status.[94]

- Lancashire Flat Cake: A lemon flavoured sponge cake, traditionally made with a couple too many eggs, best eaten after being chilled.

- Lancashire oatcake, resembling a large oval pancake, eaten either moist or dried

- "Stew and hard": a beef and cowheel stew with dried Lancashire oatcake

- Nettle porridge: a common starvation diet in Lancashire in the early 19th century. Made from boiled stinging nettles and sometimes a handful of meal.

- Ormskirk gingerbread: local delicacy that was sold throughout South Lancashire.

- Parkin: a ginger cake with oatmeal.

- Pobs or pobbies: bread and milk.

- Potato hotpot: a variation of the Lancashire Hotpot without meat that is also known as fatherless pie.

- Ran Dan: barley bread. A last resort for the poor at the end of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th century.

- Rag pudding: traditional suet pudding filled with minced meat and onions.

- Sad cake: a traditional cake that may be a variation of the more widely known Chorley cake that was once common around Burnley.

- Throdkins: a traditional breakfast food of the Fylde.

- Uncle Joe's Mint Balls: traditional mints produced by William Santus & Co. Ltd. in Wigan.[95]

Places of interest

| Key | |

| Abbey/Priory/Cathedral | |

| Accessible open space | |

| Amusement/Theme Park | |

| Castle | |

| Country Park | |

| English Heritage | |

| Forestry Commission | |

| Heritage railway | |

| Historic House | |

| Museum (free/not free) | |

| National Trust | |

| Theatre | |

| Zoo | |

The following are places of interest in the ceremonial county:

- Arnside and Silverdale AONB

- Astley Hall

- Bank Hall

- Beacon Fell

- Blackburn Cathedral

- Blackpool Pleasure Beach

- Blackpool Tower

- Blackpool Zoo

- British Commercial Vehicle Museum, Leyland

- Camelot Theme Park

- Clitheroe Castle

- Darwen Tower

- East Lancashire Railway

- Forest of Bowland: Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

- Gawthorpe Hall, Padiham

- Harris Museum

- Helmshore Mills Textile Museum

- Hoghton Tower

- Irwell Sculpture Trail

- Lancaster Castle

- Lancaster Cathedral

- Lathom Park Chapel

- Lytham Hall

- Leighton Moss nature reserve, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

- Martin Mere, Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust nature reserve, Burscough

- Morecambe Bay

- Museum of Lancashire

.png)

- Pendle Hill

- The Pennines

- Ribble Steam Railway

- Rivington Pike

- Rufford Old Hall

- Samlesbury Hall

- St Walburge's Church

- Stonyhurst College – manor house dating from 1592, now a Jesuit public school

- Towneley Hall, Burnley

- Queen Street Mill, Burnley

- West Lancashire Light Railway

- West Pennine Moors

- Williamson Park and the Ashton Memorial

- Witton Country Park

- Yarrow Valley Park

Ashton Memorial, Lancaster

Ashton Memorial, Lancaster Bank Hall, Bretherton, a Jacobean mansion house, awaiting restoration. Home to Lancashire's oldest Yew tree and one of the two fallen sequoia in the UK.

Bank Hall, Bretherton, a Jacobean mansion house, awaiting restoration. Home to Lancashire's oldest Yew tree and one of the two fallen sequoia in the UK..jpg) Blackpool Tower, completed in 1894

Blackpool Tower, completed in 1894 Rivington Pike, near Horwich, atop the West Pennine Moors, is one of the most popular walking destinations in the county; on a clear day the whole of the county can be viewed from here

Rivington Pike, near Horwich, atop the West Pennine Moors, is one of the most popular walking destinations in the county; on a clear day the whole of the county can be viewed from here Queen Street Mill, the worlds only surviving steam driven cotton weaving shed located in Burnley.

Queen Street Mill, the worlds only surviving steam driven cotton weaving shed located in Burnley.

Filmography

Whistle Down the Wind, 1961, was directed by Bryan Forbes, set at the foot of Worsaw Hill and in Burnley, and starred local Lancashire schoolchildren.

The tunnel scene was shot on the old Bacup-Rochdale railway line, location 53°41'29.65"N, 2°11'25.18"W, off the A6066 (New Line) where the line passes beneath Stack Lane. The tunnel is still there, in use as an industrial unit but the railway has long since been removed.

See also

- Custos Rotulorum of Lancashire - Keepers of the Rolls

- Healthcare in Lancashire

- High Sheriff of Lancashire

- Lancashire (UK Parliament constituency) - Historical list of MPs for Lancashire constituency

- Lancashire dialect

- Lord Lieutenant of Lancashire

- Lancashire Police

- Lancashire Police and Crime Commissioner

- Lancashire Coalfield

- List of collieries in Lancashire since 1854

- List of mining disasters in Lancashire

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Harris and Thacker (1987). write on page 252: Certainly there were links between Cheshire and south Lancashire before 1000, when Wulfric Spot held lands in both territories. Wulfric's estates remained grouped together after his death, when they were left to his brother Aelfhelm. And indeed, there still seems to have been some kind of connexion in 1086, when south Lancashire was surveyed together with Cheshire by the Domesday commissioners. Nevertheless, the two territories do seem to have been distinguished from one another in some way and it is not certain that the shire-moot and the reeves referred to in the south Lancashire section of Domesday were the Cheshire ones.

- ↑ Crosby, A. (1996). writes on page 31: The Domesday Survey (1086) included south Lancashire with Cheshire for convenience, but the Mersey, the name of which means 'boundary river' is known to have divided the kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia and there is no doubt that this was the real boundary.

- ↑ Components may not sum to totals due to rounding

- ↑ includes hunting and forestry

- ↑ includes energy and construction

- ↑ includes financial intermediation services indirectly measured

References

- ↑ "Lancashire: county history". The High Sheriff's Association of England and Wales. 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Gibb, Robert (2005). Greater Manchester: A panorama of people and places in Manchester and its surrounding towns. Myriad. p. 13. ISBN 1-904736-86-6.

- 1 2 3 4 George, D., Lancashire, (1991)

- 1 2 3 Local Government Act 1972. 1972, c. 70

- 1 2 "County Palatine". Duchy of Lancaster.

- ↑ "NWDA Chairman appointed as High Sheriff of Lancashire". Northwest Regional Development Agency. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ↑ "Lancashire: County History". The High Sherrifs' Association of England and Wales. High Sheriff's Association of England and Wales (The Shrievalty Association). Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- 1 2 Sylvester (1980). p. 14.

- ↑ Morgan (1978). pp.269c–301c,d.

- 1 2 Booth, P. cited in George, D., Lancashire, (1991)

- ↑ Phillips and Phillips (2002). pp. 26–31.

- ↑ Vision of Britain Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. – Lancashire ancient county divisions

- ↑ Berrington, E., Change in British Politics, (1984)

- 1 2 Vision of Britain Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. – Lancashire ancient county boundaries

- ↑ Lord Redcliffe-Maud and Bruce Wood. English Local Government Reformed. (1974)

- 1 2 "High Sheriff - Lancashire County History". highsheriffs.com.

- 1 2 Jones, B. et al., Politics UK, (2004)

- ↑ OPSI – The Cheshire, Lancashire and Merseyside (County and Metropolitan Borough Boundaries) Order 1993

- ↑ FORL. Retrieved 7 November 2008. Archived 8 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ ABC Counties Archived 16 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ↑ Vision of Britain Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. – Divisions of Lancashire

- ↑ Lancashire County Council Archived 15 April 2007 at Archive.is – Lancashire districts

- ↑ OPSI – The Lancashire (Boroughs of Blackburn and Blackpool) (Structural Change) Order 1996

- ↑ Lancashire County Council Archived 8 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine. – Map of Lancashire (Unitary boundaries shown)

- ↑ Government Office for the North West Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. – Local Authorities

- ↑ BUBL Information Service Archived 26 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. – The Relative Hills of Britain

- ↑ "Administrative (1974) County Tops". Hill-bagging.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ "Historic County Tops". Hill-bagging.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ "Opening of the new Town-Hall at Preston". The Times. 15 September 1882.

- ↑ "Lancashire County Council: Elections". www3.lancashire.gov.uk.

- ↑ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 15 Jun 1992". parliament.uk.

- ↑ High Sheriffs, The Times, 21 March 1985

- ↑ Christopher Thomond (13 August 2013). "Eyewitness: Lytham, Lancashire" (Image upload). The Guardian. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- 1 2 Dillon, Jonathon (26 February 2012). "'Big companies' interested in East Lancashire enterprise zone". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ Woodhouse, Lisa (23 August 2012). "Lancashire enterprize [sic] zone due in to boost jobs 18 months". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ "Enterprise zone takes off". Blackpool Gazette. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ "New Lancashire enterprise zone confirmed in Budget". Blackpool Gazette. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ "No impact on runway from redevelopment". Blackpool Gazette. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2007. Retrieved 2015-10-20. pp. 240–253 Office for National Statistics

- ↑ Transport for Lancashire – Lancashire Inter Urban Bus and Rail Map (PDF) Archived 30 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ A Vision of Britain through time. "Lancashire Modern (post 1974) County: Total Population". Retrieved 10 January 2010

- ↑ Vision of Britain Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. – Lancashire boundaries 1974

- ↑ Chandler, J., Local Government Today, (2001)

- 1 2 Youngs. Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England. Volume 2. Northern England.

- ↑ "LCCC contact details". Lccc.co.uk. 16 January 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ "List of ECB Premier Leagues". Ecb.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ "Manchester FA | About Us". Manchesterfa.com. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ "Liverpool FA | About Us". Liverpoolfa.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Fletcher, Paul (26 February 2013). "One letter, two meetings and 12 teams - the birth of league football". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2018-08-12.

- ↑ "On this day in 1888: The letter that led to the formation of The Football League". EFL Official Website. 2 March 2016. Retrieved 2018-08-12.

- ↑ "Contact Us". English Football League. Retrieved 2018-08-12.

- ↑ Airey, Tom (2012-07-06). "Why football museum moved to Manchester". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-08-12.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 September 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ↑ "Archery clubs in Lancashire". Lancashire-archery.org.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ "Bowmen of Skelmersdale". Bowmen of Skelmersdale. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- 1 2 D. Gregory, '"The Songs of the People for Me: The Victorian Rediscovery of Lancashire Vernacular Song', Canadian Folk Music/Musique folklorique canadienne, 40 (2006), pp. 12–21.

- ↑ J. Shepherd, D. Horn, and D. Laing, Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World (London: Continuum, 2003), ISBN 0-8264-7436-5, p. 360.

- 1 2 Lancashire Folk, http://www.lancashirefolk.co.uk/Morris_Information.htm, retrieved 16 February 2009.

- 1 2 G. Boyes, The Imagined Village: Culture, Ideology, and the English Folk Revival (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993), 0-71902-914-7, p. 214.

- ↑ E. D. Gregory, Victorian Songhunters: the Recovery and Editing of English Vernacular Ballads and Folk Lyrics, 1820–1883 (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 2006), ISBN 0-8108-5703-0, p. 248.

- ↑ Folk North West, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-25. , retrieved 16 February 2009.

- 1 2 P. Frame, Pete Frame's Rockin' Around Britain: Rock'n'Roll Landmarks of the UK and Ireland (London: Music Sales Group, 1999), ISBN 0-7119-6973-6, pp. 72–6.

- ↑ J, C. Falstaff, 'Roy Harper Longest Running Underground Act', Dirty Linen, 50 (Feb/Mar '94), http://www.dirtylinen.com/feature/50harper.html, 16 February 2009.

- ↑ S. Broughton, M. Ellingham and R. Trillo, World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East (Rough Guides, 1999), ISBN 1-85828-635-2, p. 67.

- ↑ 'Festivals', Folk and Roots, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-25. , retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ↑ R. Cowgill and P. Holman, Music in the British Provinces, 1690–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2007), ISBN 0-7546-3160-5, p. 207.

- ↑ R. Southey, Music-Making in North-East England During the Eighteenth Century (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2006), ISBN 0-7546-5097-9, pp. 131–2.

- ↑ D. Russell, Popular Music in England, 1840–1914: a Social History (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), ISBN 0-7190-2361-0, p. 163.

- ↑ A. Baines, The Oxford Companion to Musical Instruments (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), ISBN 0-19-311334-1, p. 41.

- ↑ D. Russell, Popular Music in England, 1840–1914: a Social History (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), ISBN 0-7190-2361-0, p. 230.

- ↑ D. Clark and J. Staines, Rough Guide to Classical Music (Rough Guides, 3rd edn., 2001), ISBN 1-85828-721-9, p. 568.

- ↑ L. Jenkins, While Spring and Summer Sang: Thomas Beecham and the Music of Frederick Delius (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2005), ISBN 0-7546-0721-6, p. 1.

- ↑ J. McCabe, Alan Rawsthorne: Portrait of a Composer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), ISBN 0-19-816693-1.

- ↑ "Biography of David Atherton (1944-VVVV)". thebiography.us.

- ↑ A. Lamb, Leslie Stuart: Composer of Floradora (London: Routledge, 2002), ISBN 0-415-93747-7.

- ↑ "Hugh Wood".

- ↑ Stephen Moss. "Profile: Peter Maxwell Davies". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Harrison Birtwistle".

- ↑ "Crosse, Gordon - NMC Recordings".

- ↑ "John McCabe - biography".

- ↑ "Schott Music - Steve Martland - Profile".

- ↑ "Simon Holt". musicsalesclassical.com.

- ↑ "Philip Cashian - Biography".

- ↑ M. Kennedy, The History of the Royal Manchester College of Music, 1893–1972 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1971), ISBN 0-7190-0435-7.

- ↑ A. H. Goldman, The Lives of John Lennon (A Capella, 2001), ISBN 1-55652-399-8, p. 92.

- ↑ "'Dreamers' star Freddie Garrity dies" Daily Telegraph, 20 May 2006. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ↑ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, p. 532.

- ↑ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1316–7.

- ↑ S. Cohen, Rock Culture in Liverpool: Popular Music in the Making (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), ISBN 0-19-816178-6, p. 14.

- ↑ Keating, Sheila (11 June 2005). "Food detective: Bury black pudding". The Times. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ↑ History of fish and chips Archived 27 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sudi Pigott (30 May 2013), Goosnagh cake, sea lavender honey, medlar butter - forgotten foods making a comeback, The Independent, accessed 3 May 2018

- ↑ "Lancashire Cheese History". Lancashire Cheese Makers. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ↑ "EU Protected Food Names Scheme: Beacon Fell traditional Lancashire cheese". Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Archived from the original on 6 November 2009. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ↑ "Uncle Joe's Mint Balls". Uncle Joe's Favourites. Wm Santus & Co. Ltd. 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

Bibliography

- Crosby, A. (1996). A History of Cheshire. (The Darwen County History Series.) Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-85033-932-4.

- Harris, B. E., and Thacker, A. T. (1987). The Victoria History of the County of Chester. (Volume 1: Physique, Prehistory, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Domesday). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-722761-9.

- Morgan, P. (1978). Domesday Book Cheshire: Including Lancashire, Cumbria, and North Wales. Chichester, Sussex: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-85033-140-4.

- Phillips A. D. M., and Phillips, C. B. (2002), A New Historical Atlas of Cheshire. Chester, UK: Cheshire County Council and Cheshire Community Council Publications Trust. ISBN 0-904532-46-1.

- Sylvester, D. (1980). A History of Cheshire. (The Darwen County History Series). (2nd Edition.) London and Chichester, Sussex: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-85033-384-9.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lancashire. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lancashire. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Lancashire. |

- Lancashire On Line Parish Clerk an active project to transcribe and publish records of Births, Marriages and Deaths in Lancashire from the time records began in Edward VIths reign

- Traditions of Lancashire, Volume 1 (of 2), by John Roby

- Lancashire Lantern, The Lancashire Life and Times E-Resource network

- Lancashire Archives' online catalogue - over 1 million descriptions of unique historical documents, accessible to the public, which tell the county's story

- Website of the film 'Catch - the hold not taken', a look at the cultural significance of wrestling in Lancashire

- Lancashire County Council – MARIO (Mapping portal)

- Map of Lancashire

- Government Office for the North West

- North West Regional Minister

- Lancashire Online Forums

- Images of Lancashire at the English Heritage Archive

- Lancashire Enterprise Zone