Watts Towers

|

Watts Towers of Simon Rodia Simon Rodia State Historic Park | |

Watts Towers | |

| |

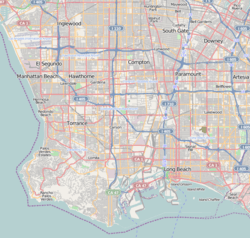

| Location | 1727 E. 107th Street, Los Angeles, California 90002 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33°56′19.46″N 118°14′27.77″W / 33.9387389°N 118.2410472°WCoordinates: 33°56′19.46″N 118°14′27.77″W / 33.9387389°N 118.2410472°W |

| Built | 1921–1954 |

| Architect | Sabato Rodia |

| NRHP reference # | 77000297 |

| CHISL # | 993 |

| LAHCM # | 15 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 13, 1977[1] |

| Designated NHL | December 14, 1990[2] |

| Designated CHISL | August 17, 1990[3] |

| Designated LAHCM | March 1, 1963[4] |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of the United States of America |

|---|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

United States portal |

The Watts Towers, Towers of Simon Rodia, or Nuestro Pueblo ("our town" in Spanish) are a collection of 17 interconnected sculptural towers, architectural structures, and individual sculptural features and mosaics within the site of the artist's original residential property in Watts, Los Angeles. The entire site of towers, structures, sculptures, pavement and walls were designed and built solely by Sabato ("Simon") Rodia (1879–1965), an Italian immigrant construction worker and tile mason, over a period of 33 years from 1921 to 1954. The tallest of the towers is 99.5 feet (30.3 m). The work is an example of outsider art or Art Brut and Italian-American naïve art.[2][5]

The Watts Towers are located near the 103rd Street/Watts Towers Los Angeles Metro station of the Los Angeles County Metro Rail Blue Line, and off the I-105 Century Freeway. They were designated a National Historic Landmark and a California Historical Landmark in 1990.[2][3] They are also a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument, and on the National Register of Historic Places in Los Angeles. The Simon Rodia State Historic Park encompasses the Watts Towers site.

Design and construction

Rodia spent 33 years building the towers on a small piece of land he had purchased shortly after moving to Watts in 1917. Before moving to the L.A. suburb, he had lived in Seattle and the San Francisco Bay Area, doing odd jobs. Divorced, estranged from his children, he came to Watts with little money or future. "I was one of the bad men in the United States," he recalled. "I was drunk all the time, always drinking."[6]

He was forty-two, barely literate, unskilled beyond the basic tasks from a life of labor. To this day no one is sure why, but in 1921 he began to build "something big." "You have to be either good good or bad bad to be remembered," he often said. "You gotta do somethin' they never got 'em in the world."[7] He began by digging a foundation, then made the rest up as he went along.

The sculptures' armatures are constructed from steel rebar and Rodia's own concoction of a type of concrete, wrapped with wire mesh. The main supports are embedded with pieces of porcelain, tile, and glass. They are decorated with found objects, including bottles, ceramic tiles, seashells, figurines, mirrors, and much more. Rodia called the Towers "Nuestro Pueblo" ("our town" in Spanish). He built them with no special equipment or predetermined design, working alone with hand tools. Neighborhood children brought pieces of broken pottery to Rodia, and he also used damaged pieces from the Malibu Pottery and CALCO (California Clay Products Company). Green glass includes recognizable soft drink bottles from the 1930s through 1950s, some still bearing the former logos of 7 Up, Squirt, Bubble Up, and Canada Dry; blue glass appears to be from milk of magnesia bottles.

Rodia bent much of the Towers' framework from scrap rebar, using nearby railroad tracks as a makeshift vise. Other items came from alongside the Pacific Electric Railway right-of-way between Watts and Wilmington. Rodia often walked the right-of-way all the way to Wilmington in search of material, a distance of nearly 20 miles (32 km).

In the summer of 1954, Rodia suffered a mild stroke. Shortly after the stroke, he fell off a tower. The fall was from a low height but at 75, he sensed the end. In 1955, Rodia quit claimed his property to a neighbor and left, reportedly tired of battling with the City of Los Angeles for permits, and because he understood the possible consequences of his aging and being alone. He moved to Martinez, California to be with his sister and never returned.

Artists and newspapers soon touted the amazing towers built by the little man who had disappeared. Then in 1961, Rodia was discovered living in Martinez. In his eighties, with broken teeth and a shock of white hair, he sat unnoticed at an art show in Berkeley where slides of his towers were shown. When the lights went up, Sam Rodia was introduced. He stood to his full 4'10". The audience stood, too, for wave after wave of applause. He bowed and tipped his hat. He died four years later.

Preservation after Rodia

Rodia's bungalow inside the enclosure burned down as a result of an accident on the Fourth of July 1956[8], and the City of Los Angeles condemned the structure and ordered it all to be destroyed. Actor Nicholas King and film editor William Cartwright visited the site in 1959, and purchased the property from Rodia's neighbor for $2,000 in order to preserve it. The City's decision to pursue expediting the demolition was still in force. The towers had already become famous and there was opposition from around the world. King, Cartwright, architects, artists, enthusiasts, academics, and community activists formed the Committee for Simon Rodia's Towers in Watts. The Committee negotiated with the city to allow for an engineering test to establish the safety of the structures and avoid demolition of the structures.

The test took place on October 10, 1959.[9] For the test, steel cable was attached to each tower and a crane was used to exert lateral force, all connected to a 'load-force' meter. The crane was unable to topple or even shift the towers with the forces applied, and the test was concluded when the crane experienced mechanical failure. Bud Goldstone and Edward Farrell were the engineer and architect leading the team. The stress test registered 10,000 lbs. The towers are anchored less than 2 feet (0.61 m) in the ground, and have been highlighted in architectural textbooks, and have changed the way some structures are designed for stability and endurance.

The Committee preserved the Towers independently until 1975 when, for the purpose of guardianship, they partnered with the City of Los Angeles. The City partnered with the State of California in 1978. The Towers are operated by the City of Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Department and curated by the Watts Towers Arts Center/Charles Mingus Youth Arts Center, which grew out of the Youth Arts Classes established in the house structure more than 50 years ago.

In February 2011, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art received a grant from the James Irvine Foundation to scientifically assess and report on the condition of the Watts Towers, to continue to preserve the undisturbed structural integrity and composition of the aging works of art.[10]

The Watts Towers are considered one of Southern California's most culturally significant public artworks.[11][12] They are one of nine folk art sites listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and were designated a National Historic Landmark in 1990.[2][5][13] The towers were also designated a California Historical Landmark in 1990.[3]

Conservation and damage

Weather and moisture have caused pieces of tile and glass to become loose on the towers, which are conserved for reattachment in the ongoing restoration work. The structures suffered little from the 1994 Northridge earthquake in the region, with only a few pieces shaken loose. A three-year restoration project by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art began in 2017 and suspends public tours within the site (tours outside of the fenced towers and sculptures are still available).[14]

Watts Towers Arts Center

The Watts Towers Arts Center is an adjacent community arts center. The current facility opened in 1970. Prior to that, the Center operated under a canopy next to the Towers.[15] The center was built and staffed by the non-profit Committee for Simon Rodia's Towers in Watts. Changing displays of contemporary artworks are on exhibit, and tours of the Watts Towers are conducted by the center. The Center's Charles Mingus Youth Arts Center holds art classes, primarily for youth and Special Needs adults from the local community and surrounding cities. Partnerships with CalArts and Sony Pictures provide media arts and piano classes. The Day of the Drum and Jazz Festival occurs annually on the last weekend of every September. It includes arts and craft booths and live music.

Guided Tours

The only guided tours of the Watts Towers are given by the Watts Towers Arts Center staff and have included access to the interior of the site. Guides explain the history and context of the towers. As of June 2017 general admission is $7.00, seniors $3.00 and children under 12 years of age are free.[16] Tours run Thursday through Saturday 10:30 am to 3:00 pm and Sundays 12:30 pm to 3:00 pm. There are no guided tours on Monday through Wednesday. NOTE: As of 2017, guided tours are no longer available within the site inside the gates for at least three years while substantial restoration is in progress. In the interim, guided tours are given from the exterior of the site only.

Special Exhibits

On-Line

A two-part digital exhibit of the Watts Towers (Part 1: Rodia's Ship; Part 2: Rodia's Pueblo) produced in 2016 by Public Art in Public Places for Google Cultural Institute's Google Arts & Culture focuses on Simon Rodia's intention to create a form of ship as well as his own pueblo or village. This Google Arts & Culture exhibit utilizes high-definition images and special digital technology for viewing image detail.[17]

Popular Culture References

In Literature

Jazz musician Charles Mingus mentioned Rodia's Towers in his 1971 autobiography Beneath the Underdog, writing about his childhood fascination with Rodia and his work. There is also a reference to the work in Don DeLillo's novel Underworld.[18]

California-based poet Robert Duncan featured Rodia's Towers in his 1959 poem, "Nel Mezzo del Cammin di Nostra Vita," as an example of democratic art that is free of church/state power structures.[19]

In his book White Sands Geoff Dyer writes about his visit to the Watts Towers in the chapter 'The Ballad of Jimmy Garrison'.

In Film

- The 1957 short documentary film The Towers, by William Hale, includes voice recordings of Rodia and footage of the artist at work.[9] The film incorrectly refers to the artist as "Simon Rodilla".

- In the 1967 movie Good Times, Sonny & Cher danced around in one of the towers.

- In the 1972 movie Melinda the title character is taken to see the towers.

- The climax of the 1976 blaxploitation movie Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde takes place at the towers.

- The climax of the 1977 blaxploitation movie Abar, the First Black Superman takes place at the towers.

- The 1988 movie Colors ends with Sean Penn near the towers.

- The 1991 movie Ricochet, starring Denzel Washington, climaxes with Denzel's character swinging on the towers.

- The 1993 movie CB4 shows Chris Elliott recording a piece for his character's documentary in front of the towers.

- The 1993 movie Menace II Society shows the towers at the beginning of the 1993 introduction.

- The 2006 documentary I Build the Tower focuses on Sabato "Simon" Rodia, and his creative vision and skill in building the Towers. The 1987 docudrama Daniel and The Towers is about them also. The Towers of Simon Rodia is a 2008 documentary filmed in digital 3-D.[20]

- The 2016 movie La La Land shows the film's main characters visiting the towers in a montage sequence.

In Television

The Watts Towers were highlighted in the 1973 BBC television series The Ascent of Man, written and presented by Jacob Bronowski, in the episode "The Grain in the Stone — tools, and the development of architecture and sculpture".

- The towers were also depicted on The Simpsons episode "Angry Dad: The Movie".[21]

- The towers are referenced in Dragnet season 2 episode 4.

- The towers appear and are discussed by student artists Claire Fisher and Russel Corwin in "Nobody Sleeps", the Season 3 Episode 4 of Six Feet Under.

- The towers appear and are discussed in 2017 Season 1, Episode 1 of the Amazon Originals production of "Long Strange Trip"

- Watts tower are Also in “the White Shadow” season 3 episode 9 B.M.O.C

On Radio

- In an August 2017 episode of BBC Radio 4's The Museum of Curiosity, California-born textile artist Kaffe Fassett chose the Watts Towers as his hypothetical donation to this imaginary museum.[22]

In Video games

- The 2004 game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas features the Jefferson Towers (also named as Sculpture Park) in the city of Los Santos, based on the Watts Towers.

- The 2005 street racing game LA Rush features the Watts Towers.

- The 2008 street racing game Midnight Club: Los Angeles features the Watts Towers.

- The 2013 game Grand Theft Auto: V similarly features the Watts Towers, but in this version named as Rancho Towers.

- The 2014 game Wasteland 2 features the Watts Towers as part of the town of Rodia.

See also

Local landmarks

- List of Registered Historic Places in Los Angeles.

- List of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments in South Los Angeles

- California Historical Landmarks in Los Angeles County, California

- List of Public Art in Los Angeles - Public Art in Public Places Project

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Los Angeles, California

Regional and international landmarks

- United States

- Baldasare Forestiere, another Italian immigrant in California (born the same year as Rodia), who built the Forestiere Underground Gardens in Fresno.

- Nitt Witt Ridge, an eclectic assemblage house in Cambria, California.

- Rubel Castle, a folk art sculptural house in Glendora, California.

- Bishop Castle, a massive stone castle hand built by Jim Bishop near Rye, Colorado.

- Mystery Castle, a house in Phoenix, Arizona, built in the 1930s in a similar style.

- Wharton Esherick Studio, built by American sculptor Wharton Esherick in Malvern, Pennsylvania.

- Coral Castle, a stone artwork and residence built in Homestead, Florida.

- Philadelphia's Magic Gardens, by mosaic artist Isaiah Zagar, an art space occupying three city lots created over the span of fourteen years.

- Heidelberg Project, a street in Detroit where houses have been turned into an outdoor art environment.

- Broken Angel House, in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, designed with similar ad hoc construction for more than 30 years.

- Kea Tawana, Japanese-American sculptor who built an ark from architectural salvage in Newark, New Jersey

- Salvation Mountain, in Imperial County, CA, built by Leonard Knight.

- Noah Purifoy, an African American visual artist and sculptor who co-founded the Watts Towers Art Center and created the Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum near the Mojave Desert town of Joshua Tree, CA.

- International

- Edward James, surrealist poet inspired by Rodia. James built "Las Pozas" in San Luis Potosí state, México.

- Hermit House, a unique residence in Israel, with intricate mosaics created by an artist over thirty years.

- Ferdinand Cheval, a French postman who constructed an "ideal palace" out of rocks in his spare time.

- Rock Garden, Chandigarh, a rock garden built completely out of thrown-away items. The project was secretly initiated by Nek Chand.

- Justo Gallego Martínez, a Spaniard who built his own cathedral.

- Valerio Ricetti, an Italian immigrant in Australia who built the Hermit's Cave.

- Antoni Gaudí, Catalan architect with a similar Expressionist style, particularly La Sagrada Família in Barcelona.

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 "Watts Towers". National Historic Landmark Quicklinks. National Park Service. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Watts Towers". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ↑ Department of City Planning. "Designated Historic-Cultural Monuments". City of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2010-06-09. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- 1 2 Goldstone, Arloa Paquin (1990-06-18). "The Towers of Simon Rodia". National Register of Historic Places Registration. National Park Service.

- ↑ "The Towers of Watts". The Attic. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ de Arend, Lucien. "The History of the Watts Towers". Watts Towers by Sam Rodia. Cultural Affairs Dept. Watts Center. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- 1 2 Goldstone, Bud; Goldstone, Arloa Paquin (1997). The Los Angeles Watts Towers. Getty Conservation Institute. ISBN 978-0892364916.

- ↑ Boehm, Mike (2011-02-11). "LACMA gets $500,000 grant to fund its new role as Watts Towers conservator". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ ""Watts Towers" or "Nuestro Pueblo" (1921-1954) by Sabato (Simon) Rodia - PUBLIC ART IN PUBLIC PLACES". www.publicartinpublicplaces.info. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ "PUBLIC ART IN PUBLIC PLACES". www.publicartinpublicplaces.info. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Towers of Simon Rodia, Accompanying 8 photos, from 1967–1989". National Register of Historic Places Registration. National Park Service. 1990-06-18.

- ↑ Nguyen, Arthur (July 14, 2016). "Conservation Proceeds at Watts Towers". LACMA. Un Framed. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Wattstowers.us: The Watts Towers Arts Center, and Charles Mingus Youth Arts Center.

- ↑ "Watts Towers Schedule and Prices". Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ "Google Arts & Culture | Public Art in Public Places". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Duvall, John N. (29 May 2008). "The Cambridge Companion to Don DeLillo". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 12 August 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Fredman, Stephen (12 August 2018). "Contextual Practice: Assemblage and the Erotic in Postwar Poetry and Art". Stanford University Press. Retrieved 12 August 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ The Towers of Simon Rodia (2008), with the documentary short Watts Towers – Then & Now — available on a DVD (2-D or 3-D) from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art bookshop.

- ↑ Ng, David (February 21, 2011). "The Simpsons' pays tribute to Watts Towers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Episode 3 Series 11". The Museum of Curiosity. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Watts Towers. |

- Public Art in Public Places: "Watts Towers" or "Nuestro Pueblo" (1921–1954), Los Angeles

- Watts Towers Arts Center

- Simon Rodia State Historic Park website

- Watts Towers on Great Buildings www.greatbuildings.com: Watts Towers

- The Towers — 1957 documentary