Uptown Hudson Tubes

Route map:

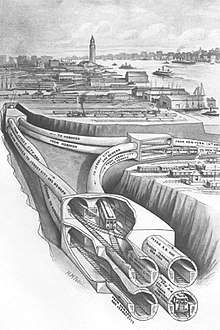

Junction in Jersey City at tubes' west end from a 1909 illustration | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Hudson River; Midtown Manhattan |

| Coordinates | 40°43′48″N 74°01′14″W / 40.7301°N 74.0205°W |

| System | PATH |

| Start |

Christopher Street (underwater section) 33rd Street (full line) |

| End | between Hoboken Terminal and Newport |

| Operation | |

| Constructed | 1874-1906 |

| Opened | February 26, 1908 |

| Operator | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey |

| Traffic | Railroad |

| Character | Rapid transit |

| Technical | |

| Design engineer | Charles M. Jacobs |

| Length |

5,650 ft (1,722 m) underwater 3 miles (4.8 km) total |

| No. of tracks | 2 |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Electrified | 600 V DC Third rail |

| Tunnel clearance |

15.25 feet (4.65 m) diameter (southern tube) 18 feet (5.5 m) diameter (northern tube) |

| Depth of tunnel below water level | 97 ft (29.57 m) below river level |

Uptown Hudson Tubes | |

The Uptown Hudson Tubes are a pair of tunnels that carry PATH trains between Manhattan in New York City, New York, to the east and Jersey City in New Jersey to the west. The tubes originate at a junction of two PATH lines on the New Jersey shore, cross eastward under the Hudson River. On the Manhattan side, the tubes run mostly underneath Christopher Street and Sixth Avenue, making four intermediate stops before terminating at 33rd Street station. Contrary to their name, the tubes do not actually enter Uptown Manhattan, but are so named because they are located to the north of the Downtown Hudson Tubes, which connect Jersey City and the World Trade Center.

Dewitt Clinton Haskin first attempted to construct the Uptown Hudson Tubes in 1873. Work was delayed by five years by a lawsuit, and was further disrupted by an accident in 1880, which killed twenty workers. The project was subsequently canceled in 1883 due to a lack of money. A British company attempted to complete the tunnels in 1888, but also ran out of money by 1892, by which point the tunnels were nearly half-finished. In 1901, a company formed by William Gibbs McAdoo resumed work on the tubes, and by 1907, the tunnels had been fully bored. The Uptown Hudson Tubes opened to passenger service in 1908 as part of the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (H&M) and were completed by 1910.

After the Uptown Hudson Tubes' opening, the H&M proposed extending the tubes northward to Grand Central Terminal, as well as creating a crosstown spur line that would run under Ninth Street in Manhattan. However, neither extension was ultimately constructed. In the 1930s, parts of the tubes under Sixth Avenue were rebuilt due to the construction of the Independent Subway System (IND)'s Sixth Avenue Line. The Uptown Hudson Tubes had originally contained seven stations, but two were later closed, and the 33rd Street terminal was rebuilt. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey took over the H&M and the tunnels in 1962, rebranding the H&M as part of the PATH system.

Description

The Uptown Hudson Tubes use a roughly east-west path under the Hudson River, connecting Manhattan in the east of Jersey City in the west. On the Manhattan side, the tunnels initially take an eastward trajectory under Morton Street.[1] At Greenwich Street, the tubes curve sharply north, then continue two blocks before turning sharply east under Christopher Street. This sharp curve, which follows the streets above it, was necessitated to avoid the demolition of preexisting basements during construction.[2]

The "Uptown Hudson Tubes" name also applies to the section of the subway under Christopher Street and Sixth Avenue in Manhattan.[3][4] The first PATH stop in New York is at the Christopher Street station, and service in New York continues uptown to the 33rd Street terminal, making intermediate stops at 9th Street, 14th Street, and 23rd Street.[5] Two more stations formerly existed at 19th Street and 28th Street. The ornately designed stations in Manhattan featured straight platforms, each 370 feet (110 m) long and able to accommodate 8-car consists.[6] The stations underneath Sixth Avenue (14th, 19th, 23rd, and 28th Streets, and the original 33rd Street Terminal) contained round columns with scrolls and the station name near the ceilings. The exposed steel rings of the tunnel's structure can be seen at Christopher and Ninth Streets.[7]

On the Jersey City side, the tunnels leave the riverbank approximately parallel to 15th Street[1] and enter a flying junction where trains can proceed to either Hoboken Terminal to the north or Newport station to the south.[8]

The Uptown Hudson Tubes measure 5,500 feet (1,700 m)[9]:11 or 5,650 feet (1,720 m) between shafts.[10]:22[6][11] The tubes descend up to 97 feet (30 m) below mean river level.[6][11] In both the uptown and downtown tubes, each track is located in its own tunnel,[6] which enables better ventilation by the so-called piston effect. When a train passes through the tunnel it pushes out the air in front of it toward the closest ventilation shaft, and also pulls air into the rail tunnel from the closest ventilation shaft behind it.[12] The diameter of the Uptown Tunnels' southern tube and both downtown tubes is 15 feet 3 inches (4.65 m); the more northerly of the two uptown tubes is slightly larger, with a diameter of 18 feet (5.5 m) because that tube had been constructed first.[13] Shield tunneling was used only between the Uptown Tunnels' western end in Jersey City and 12th Street in Manhattan. North of 12th Street, the circular tubes transition into two rectangular tunnels, which measure 14.5 feet (4.4 m) high by 13 feet (4.0 m) wide and carry one track each.[14]

History

Initial construction attempts

In 1873, a wealthy Californian, Dewitt Clinton Haskin, formed the Hudson Tunnel Company to construct a tunnel under the Hudson River. The tube would run from 15th Street in Jersey City to Morton Street in Manhattan, a distance of 5,400 feet (1,600 m).[6][9]:14[13][15]:107 He hired Trenor W. Park as the president of the new company.[16] Haskin initially sought $10 million in funding to pay for the tunnel.[10]:12 At the time, constructing a tunnel under the mile-wide river was considered less expensive than trying to build a bridge over it. An initial attempt to construct the Hudson River tunnel began in November 1874 from the Jersey City side.[9]:14 When the tunnel was completed, it would be 12,000 feet (3,700 m) feet long. Trains from five railroad companies on the New Jersey side would enter one of two tubes, hauled by special steam locomotives that would be able to emit very little steam. The engines would continue to Manhattan, terminating at a railroad hub in Washington Square Park.[13] This tunnel project was known as the Morton Street Tunnel.[17]

Work progressed only for one month when progress was stopped by a court injunction brought about by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, who owned the property at the tunnel's New Jersey portal.[13][18] Due to the lawsuit, work on the tunnel was not resumed until September 1879.[9]:14-15[10]:12[19]

The construction method at the time did not use a tunneling shield, but it did use air compressors to maintain pressure against the water laden silt that was being tunneled through. Haskin believed the river silt was strong enough to maintain the tunnel's form, with the help of compressed air, until a 2-foot-6-inch-thick (76 cm) brick lining could be constructed. Haskin's plan was to excavate the tunnel, then fill it with compressed air to expel the water and to hold the iron plate lining in place.[6] However, the amount of pressure needed to hold back the water at the bottom of the tube was much greater than the pressure needed to hold back the water at the top. On July 21, 1880, an overpressure blowout at the tube's top caused an accident that resulted in an air lock jam, trapping several workers and killing 20.[10]:12[15]:107[20][21] A memorial to the workers killed was later erected in Jersey City.[22]

The liabilities incurred as a result of the accident meant that tunnel work was again stopped on November 5, 1882, since the company had run out of money. At that time water was allowed to fill the unfinished tunnel. On March 20, 1883, the air and compressors were turned back on and the tunnel was drained for a resumption of work. Work continued for the next four months when on July 20, 1883, it was stopped once more due to lack of funds.[13][9]:67 By that time, about 1,200 feet (370 m) of the tunnel's route had been constructed.[10]:12 This included 1,500 feet (460 m) of one tube and 600 feet (180 m) of a parallel tube to the south.[13]

In 1888, a British company attempted to resume work on the Morton Street Tunnel, employing James Henry Greathead as a consulting engineer and S. Pearson & Son as principal contractors.[10]:13 S. Pearson & Son then received the Morton Street Tunnel's construction contract from Haskin's company.[16] The firm used Greathead's then-new device, called the "Greathead Shield", to extend the tunnel by 1,600 feet (490 m).[10]:13 As there was a concentration of rock directly underneath the clay riverbed, the tube would have to pass directly over the concentration of rock, with very little clearance. To maintain sufficient air pressure in the tube, S. Pearson & Son decided to place a silt layer of at least 15 feet (4.6 m) above the tube, then remove the silt layer after the tube was finished and thus able to maintain its own air pressure.[16][10]:17

S. Pearson & Son could not complete the tubes, as they were also out of funds by 1891.[15]:107-108 Work stopped completely in 1892 after the company had completed another 2,000 feet (610 m) of digging.[13][6] At this point, the pair of tubes had been dug from both sides of the river. The northern tube, extended 4,000 feet (1,200 m) from the New Jersey shore and 150 feet (46 m) from the New York shore, with a gap of 1,500 feet (460 m) between the two ends of the tube. The southern tube had only been dug 1,000 feet (300 m) from the New Jersey shore and 300 feet (91 m) from the New York shore.[16]

Completion of construction

In 1901, a Tennesseean named William Gibbs McAdoo casually mentioned the idea of a Hudson River tunnel to John Randolph Dos Passos, a lawyer who had invested in the original tunneling project.[6][10]:14 Through this conversation, McAdoo learned about the previous Hudson tunnel effort. He went to explore it with Charles M. Jacobs, an engineer who had built New York City's first underwater tunnel in 1894 under the East River. Jacobs had also worked on the incomplete Hudson River tunnel.[6][10]:15 McAdoo and consulting engineer J. Vipond Davies believed that the existing work was still salvageable. McAdoo formed the New York and Jersey Tunnel Company in 1902, raising $8.5 million in capital stock for the company.[23] Unlike the North River Tunnels upstream, which would carry intercity and commuter trains, the Morton Street Tunnel would carry only trolleys or rapid transit.[17]

McAdoo's original intention had been simply to complete the northern tube of the Morton Street Tunnel, which was further along in the construction process. Afterward, he would operate a narrow-gauge railway with two small carriages going back and forth within that one tube.[10]:15[13] However, after thinking about the ferry congestion at Cortlandt Street Ferry Depot in Lower Manhattan, he devised plans to create a network of train lines connecting New Jersey and New York City.[13] The Morton Street Tunnel became known as the Uptown Hudson Tubes, complementing a pair of downtown tunnels connecting Jersey City, New Jersey, with Lower Manhattan.[10]:15 The idea for the downtown tunnels was actually devised by another company in 1903, the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Corporation (H&M), but McAdoo's New York and Jersey Railroad Company was interested in the H&M tunnel.[24]

The new effort to build the Uptown Tubes, led by chief engineer Charles M. Jacobs, employed a different method of tunneling using tubular cast iron plating and a tunneling shield at the excavation site. The large mechanically jacked shield was pushed through the silt at the bottom of the river, and the silt went through the bulkhead of the shield, which faced the portion of the tunnel that had already been dug.[17] The bulkhead contained a pressurized air lock in order to avoid sudden blowouts, such as had occurred during the original construction. The air pressure was maintained at 38 pounds per square inch (260 kPa).[11][10]:17 The excavated mud would be carted away to the surface using battery-operated electric locomotives running on a temporary narrow-gauge railway. In some cases, the silt would be baked with kerosene torches to facilitate easier removal of the mud. The cast iron lining would then be placed on the tunnel wall immediately after the shield had been pushed through, so that no silt could be seen on the tube wall behind the shield's bulkhead. These iron plates were then bolted shut to prevent leakages, as well as to maintain low air pressure in the tunnel.[10]:17[17] McAdoo later wrote that the Uptown Tubes was the first project where machines, rather than workers, carted out the excess silt.[6]

Owing to the previous work that had been performed on the Morton Street Tunnel, the tunnel project was half-completed a year after McAdoo's company started digging. By 1903, there was a gap of only a few feet between the two sections of the northern tube.[17] As a result, the tubular cast iron and tunneling shield method was mostly used on the southern tube.[10]:17[17] For the southern tube, the tunneling shield progressed from the New Jersey side.[25] Some difficulties arose during the completion of the northern tube: the company had to use dynamite to tunnel through a hard reef on the Manhattan side, and one explosion killed a worker.[6] The two parts of the northern tube were connected in March 1904, accompanied by a large celebration that involved a group of 20 men walking through the completed tube from end to end.[26][10]:17–18

By the end of 1904, the New York and Jersey Railroad Company had received permission from the New York City Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners to build a new subway line through Midtown Manhattan, which would connect with the Uptown Hudson Tubes; the company received the sole rights to operate this line for a duration of 25 years. The Midtown Manhattan line would travel eastward under Christopher Street before turning northeastward under Sixth Avenue, then continue underneath Sixth Avenue to a terminus at 33rd Street. The New York City Board of Aldermen implied that the line could be extended further north to Central Park in the future. McAdoo's company would also retain perpetual rights to build and operate an east-west crosstown line under Christopher and Ninth Streets eastward to either Second Avenue or Astor Place,[27][10]:22 with no intermediate stops.[28] This option was never fully exercised, as the crosstown line was only dug about 250 feet (76 m); the partly completed crosstown tube still exists.[10]:22[6] In January 1905, the Hudson Companies was incorporated for the purpose of completing the Uptown Hudson Tubes and constructing the Sixth Avenue line. The company, which was contracted to construct the Uptown Hudson Tubes' subway tunnel connections on each side of the river, already had a capital of $21 million.[29]

The Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company (H&M) was incorporated in December 1906 to operate a passenger railroad system between New York and New Jersey via the Uptown and Downtown Tubes.[30][31] The Downtown Tubes, located about 1.25 miles (2.01 km) south of the first pair, had started construction by that point.[10]:19 The next year, the Uptown Tubes were completed after 33 years of intermittent effort, and as such, were celebrated as the first non-waterborne link between Manhattan and New Jersey.[32][15]:132 Work continued on finishing off the interior of the uptown tubes. The final work included the completion of a concrete lining, which replaced the original brick lining, as well as laying tracks and electric third rails; this took an additional year to complete. The stations on the Manhattan side were also completed during this time.[6][11] Test runs of trains without passengers started through the tunnels in late 1907:[33] the Hudson Companies tested its rolling stock on the Second Avenue Elevated, then delivered the trains to the Uptown Hudson Tubes for further testing.[6]

Service begins

A trial run, carrying a party of officials, dignitaries, and news reporters, ran on February 15, 1908.[34] The first "official" passenger train, which was also open only to officials and dignitaries, left 19th Street at 3:40 p.m. on February 25, 1908, and arrived at Hoboken Terminal ten minutes later.[6][35][10]:21 The tubes opened to the general public at midnight the next day.[35] At the time, three more stations at 23rd Street, 28th Street, and 33rd Street were under construction,[34] and there were plans to extend the H&M line northeast to Grand Central Terminal, at Park Avenue and 42nd Street.[36] The 23rd Street station opened on June 15, 1908.[37] In the coming years, many businesses moved to Sixth Avenue, along the route of the Uptown Hudson Tubes, while commuters moved to New Jersey to take advantage of the 10-minute commute to Manhattan.[6][11] There were also new developments centered around Hoboken Terminal.[38]

On July 19, 1909, service via the downtown tubes began between Hudson Terminal in Lower Manhattan and Exchange Place in Jersey City.[39] By this time, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) had become a viable competitor, as its Lexington Avenue line was proposed to connect to the H&M at three locations once the planned system was complete. The Sixth Avenue portion of the H&M line also marginally duplicated the IRT's Sixth Avenue elevated, but the elevated served a longer segment of Sixth Avenue, as it extended both north of 33rd Street and south of 9th Street.[36]

McAdoo wanted to extend the uptown tubes under Sixth Avenue to 42nd Street, where they would curve east under the IRT's 42nd Street Line and terminate at Park Avenue. There would be two intermediate stops at 39th Street/Sixth Avenue and 42nd Street/Fifth Avenue.[28] The proposed expansion of the Uptown Tubes to Grand Central soon encountered problems. At Grand Central, the H&M platforms would be directly below the 42nd Street Line's platforms, but above the IRT's Steinway Tunnel that carried the Flushing Line to Queens. However, the IRT constructed an unauthorized ventilation shaft between the 42nd Street line and the Steinway Tunnel. This would force the H&M to build its station at a very low depth, thus making it harder for any passengers to access the H&M station.[40] As an alternative, it was proposed to connect the Uptown Tubes to the Steinway Tunnel.[41]

A franchise to extend the Uptown Tubes to Grand Central was awarded in June 1909, with the expectation that construction could start within six months and that the new extension would be ready by January 1911.[42] However, by February 1910, financing had only been secured for the completion of the 33rd Street terminal, and not for the Grand Central extension.[43] The extension to 33rd Street opened on November 10, 1910.[44] By 1914, the H&M had not started construction of the Grand Central extension yet, and it wished to delay the start of construction further. The Rapid Transit Commissioners had determined that the Ninth Street crosstown spur was unlikely to start construction any time soon.[45] By 1920, the H&M had submitted seventeen applications in which they sought to delay construction of the extensions; in all seventeen instances, the H&M had claimed that it was not an appropriate time to construct the tube.[46] This time, however, the Rapid Transit Commissioners declined this request for a delay, effectively ending the H&M's right to build an extension to Grand Central.[10]:55–56

Reconfiguration underneath Sixth Avenue

In 1924, the city-operated Independent Subway System (IND) submitted its list of proposed subway routes to the New York City Board of Transportation. One of its proposed routes, the Sixth Avenue Line, was to run parallel to the Uptown Hudson Tubes from Ninth to 33rd Streets.[47] At first, the city intended to take over the portion of the Uptown Tubes under Sixth Avenue for IND use, then build a pair of new tubes for the H&M directly underneath it. The IND had committed to building the Sixth Avenue line, and the H&M's 33rd Street terminal was located both above and below preexisting railroad tunnels, hence the IND's plan to convert part of the H&M tubes.[48] However, the H&M objected, and so negotiations between the city and IND and the H&M continued for several years.[49]

The IND and H&M finally came to an agreement in 1930. The city had decided to build the IND Sixth Avenue Line's local tracks around the pre-existing H&M tubes, and add express tracks for the IND underneath the H&M tubes at a later date.[50] However, the city still planned to eventually take over the H&M tracks, convert them to express tracks for the IND line, then build a lower level for the H&M.[51] As part of the construction of the IND line, the H&M's 14th Street and 23rd Street stations had to be rebuilt to provide space for the IND's 14th Street and 23rd Street stations, which would be located at a similar elevation. The 19th Street station was not affected because the IND tracks were located below the H&M tracks at that point.[52]

The 33rd Street terminal closed on December 26, 1937 and service on the H&M was cut back to 28th Street to allow for construction on the subway to take place.[53] The 33rd Street terminal was moved south to 32nd Street and reopened on September 24, 1939. The city had to pay $800,000 to build the new 33rd Street station and reimbursed H&M another $300,000 to the H&M for the loss of revenue.[54] The 28th Street station was closed at this time because the southern entrances to the 33rd Street terminal were located only two blocks away, rendering the 28th Street stop unnecessary. It was demolished to make room for the IND tracks below.[55] The IND line opened in December 1940.[52] It replaced the Sixth Avenue elevated, which was closed in December 1938[56] and demolished soon after.[52]

Later years

The 19th Street station was closed in 1954. The only entrance to the station's westbound platform had been located inside a building, whose owner had canceled the lease for the station entrance. The H&M believed that constructing a new entrance was too expensive, and so the station was closed.[57] In 1962, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey took over the H&M's operations, and the H&M system was rebranded as the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH).[58]

In 1961, as part of the Chrystie Street Connection and DeKalb Avenue Junction project, the city started building a pair of express tracks for the IND Sixth Avenue Line. Although the tracks were located 80 feet (24 m) below ground level, they were directly underneath the portion of the Uptown Tubes that ran along Sixth Avenue.[59][60] The ceiling of the express tunnel was located 38 feet (12 m) underneath the bottom of the Uptown Tubes.[61] Service on the Uptown Tubes was suspended for five days in 1962 when it was found that the express-track construction project had drilled to an "unsafe" margin of 18 feet (5.5 m) underneath the Uptown Tubes.[61][62] The express tracks opened in 1967.[63]

The stations along the Uptown Tubes started to age, and in 1986, the New Jersey-bound platform at 14th Street and both platforms of Christopher Street were closed for three months of renovations.[7]

Awards

The uptown and downtown Hudson tubes were declared a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1978 by the American Society of Civil Engineers.[11]

The coal-fired Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Powerhouse was built in 1906-1908 and generated electricity to run the Hudson tube trains. The powerhouse stopped generating in 1929. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 23, 2001.[64][65]

See also

References

- 1 2 "WALK THROUGH HUDSOH TUNNEL; An Inspection Party Strolls from An Jersey City to Manhattan Dryshod. CURVE AT NEW YORK SHORE Bore Diverted to Avoid Appraiser's Stores -- Last Caisson Down In Dey Street Terminal To-day". The New York Times. May 23, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "WALK THROUGH HUDSOH TUNNEL; An Inspection Party Strolls from An Jersey City to Manhattan Dryshod. CURVE AT NEW YORK SHORE Bore Diverted to Avoid Appraiser's Stores -- Last Caisson Down In Dey Street Terminal To-day". The New York Times. May 23, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ Jackson, Dugald Caleb; McGrath, David James (1917). Street Railway Fares, Their Relation to Length of Haul and Cost of Service: Report of Investigation Carried on in the Research Division of the Electrical Engineering Department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. McGraw-Hill book Company, Incorporated.

- ↑ Shaw, A. (1910). Review of Reviews and World's Work. p. 434. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Maps - PATH". www.panynj.gov. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Fitzherbert, Anthony (June 1964). "The Public Be Pleased: William Gibbs McAdoo and the Hudson Tubes". Electric Railroaders' Association. Retrieved April 24, 2018 – via nycsubway.org.

- 1 2 Anderson, Susan Heller; Dunlap, David W. (May 27, 1986). "NEW YORK DAY BY DAY; PATH Recalls Early Years". The New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ Brooks, Benjamin (September 1908). "The Contracting Engineer". Scribner's Magazine. XLIV (3): 272.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burr, S.D.V. (1885). Tunneling Under The Hudson River: Being a description of the obstacles encountered, the experience gained, the success achieved, and the plans finally adopted for rapid and economical prosecution of the work. New York: John Wiley and Sons. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "History and Heritage of Civil Engineering: Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Tunnel". American Society of Civil Engineers. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ↑ Davies, John Vipond (1910). "The Tunnel Construction of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. 49: 164–187. JSTOR 983892.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "The Worlds Greatest Inter-Urban Tunnels" (PDF). Evening Star. Washington D.C. June 24, 1905. p. 2. Retrieved April 24, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ The World Almanac and Encyclopedia. Press Publishing Company (The New York World). 1911. p. 792. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Jacobs, David; Anthony E. Neville (1968). Bridges, Canals & Tunnels: The engineering conquest of America. New York: American Heritage Publishing Co. Inc. with the Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-442-04040-7.

- 1 2 3 4 "THE HUDSON RIVER TUNNEL.; EFFORT MAKING TO RAISE SUFFICIENT MONEY TO COMPLETE IT". The New York Times. March 18, 1893. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "WORK ON NEW JERSEY TUNNEL; HAIRDRESSERS OF THE EAST SIDE Their Services in Constant Demand on Account of Frequent Weddings. MEDICINE FOR TREES. Park Department Applying Disinfectant to Kill Off the Caterpillars". The New York Times. April 26, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "THE HUDSON RIVER TUNNEL.; CHANCELLOR RUNYON GRANTS AN INJUNCTION PRACTICALLY ENDING THE WORK THE CASE TO BE TAKEN BEFORE JUDGE DEPUE". The New York Times. January 2, 1875. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ "WORK ON THE TUNNEL RESUMED". The New York Times. July 23, 1879. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ Fitzherbert, Anthony (June 1964). ""The Public Be Pleased": William G. McAdoo and the Hudson Tubes". Electric Railroaders Association. Retrieved March 14, 2009 – via nycsubway.org.

- ↑ "TWENTY MEN BURIED ALIVE; CAVING IN OF THE HUDSON RIVER TUNNEL. THE STORY OF THE DISASTER. STORY OF A SURVIVOR. WHAT ANOTHER WORKMAN SAYS. THE LOST AND THE SAVED. WHAT THE SUPERINTENDENT SAYS. CHARACTER OF THE ENTERPRISE. WHERE THE "BLOW-OUT" OCCURRED. CONSULTATION OF ENGINEERS. WHO IS AT FAULT?". The New York Times. July 22, 1880. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Long before PATH trains, tragedy struck inside Hudson River tunnel". NJ.com. May 2, 2017. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ↑ "UNDER RIVER BY TROLLEY; New York and Jersey Railroad Company Incorporated. Concern Capitalized at $8,500,000 Will Complete the Old Hudson River Tunnel". The New York Times. February 12, 1902. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ "ANOTHER TUNNEL SCHEME; Company Formed to Drive One Under the North River. Would Extend from Cortlandt Street and Broadway to Jersey City -- Purchases of Property Made". The New York Times. March 21, 1903. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ "COUPLING HEADINGS OF NORTH RIVER TUNNEL; Several Days Before Tube to New Jersey Can Be Opened. WHAT REMAINS TO BE DONE No Car Service Till the Second Tube Shall Have Been Completed, Probably a Year Hence". The New York Times. March 10, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "HUDSON TUNNEL OPEN END TO END; Party of Twenty Walk Under River to Jersey City. LAST HEADINGS ARE COUPLED President McAdoo Unexpectedly Summoned to Make the First Trip Through the Bore". The New York Times. March 12, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "M'ADOO SUBWAY WINS FIGHT FOR FRANCHISE; Crosstown Line Perpetual -- 25 Years Under Sixth Avenue". The New York Times. December 16, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- 1 2 "In 1874, a Daring Downtown Plan: Build a Train Tunnel Under the Hudson". Tribeca Trib Online. 2018-04-23. Retrieved 2018-05-02.

- ↑ "$21,000,000 COMPANY FOR HUDSON TUNNELS; Will Also Build Ninth Street and Sixth Avenue Subways. FOR CENTRAL PARK ROUTE? Rapid Transit Board Hints at It in Recommending McAdoo Underground Routes to Aldermen". The New York Times. 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ The Commercial & Financial Chronicle ...: A Weekly Newspaper Representing the Industrial Interests of the United States. William B. Dana Company. 1914.

- ↑ "$100,000,000 CAPITAL FOR M'ADOO TUNNELS; Railroad Commission Agrees to Issuance of Big Mortgage. McADOO EXPLAINS PROGRESS The Work Very Expensive, but Going on Rapidly -- New Bonds to Take Up Old Issues". The New York Times. 1906-12-12. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ "Under the Hudson River by Tunnel About to Become a Reality; October 1 Will See the End of a Romance of Thirty-four Years' Struggle of Capital and Brains Against the Seemingly Insurmountable Obstacles of Nature". The New York Times. May 26, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "UNDER THE HUDSON BY TRAIN.; First Trip Through Christopher Street Tubes to be Made To-day". The New York Times. December 18, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- 1 2 "IN M'ADOO TUNNEL TO JERSEY, FAST RUN; Fifteen Minutes from Fourteenth Street to Hoboken on Trial Trip Yesterday. NOVEL FEATURES IN CARS Stations Which Avoid Crush of Incoming and Outgoing Passengers -- Open for Travel Feb. 25. IN M'ADOO TUNNEL TO JERSEY, QUICK RUN". The New York Times. February 16, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- 1 2 "TROLLEY TUNNEL OPEN TO JERSEY; President Turns On Power for First Official Train Between This City and Hoboken. REGULAR SERVICE STARTS Passenger Trains Between the Two Cities Begin Running at Midnight. EXERCISES OVER THE RIVER Govs. Hughes and Fort Make Congratulatory Addresses -- Dinner at Sherry's in the Evening". The New York Times. February 26, 1908. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- 1 2 "TWO NEW SUBWAYS NOW BEING PLANNED; Interborough and McAdoo Interests Likely to Build East and West Side Systems. COMPLETE UNIFIED SYSTEM Traction Interests Disclaim Anything More Than a Tentative Interest at This Time". The New York Times. February 14, 1909. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "TO EXTEND HUDSON TUNNEL.; Trains to Begin Running to Twenty-third Street on Monday". The New York Times. June 12, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Skyscraper Construction Now Invading Hoboken; New Office Building for Site Near Tunnel Terminal -- Increasing Values Near the Business Centre". The New York Times. 1909-06-06. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ↑ "40,000 CELEBRATE NEW TUBES' OPENING; Downtown McAdoo Tunnels to Jersey City Begin Business with a Rush. TRIP TAKES THREE MINUTES Red Fire and Oratory Signalize the Event -- Speeches by Gov. Fort and Others -- Ovation to Mr. McAdoo". The New York Times. 1909-07-20. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ "INTER-TUNNEL SHAFT IN M'ADOO'S WAY; Connects Subway and Steinway Tunnel Through Third Level Under 42d Street. WHO AUTHORIZED IT THERE? Public Service Board Likely to Ask Questions -- If It Stays, McAdoo People Must Go Lower". The New York Times. March 26, 1909. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "MAY CONNECT M'ADOO AND STEINWAY TUBES; Utilities Board Suggests Such a Junction to the Board of Estimate. McADOO FRANCHISE SAFE Commission Says the 42d Street Extension Won't Interfere with Other Subways". The New York Times. 1909-05-06. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ "M'ADOO EXTENSION TO BE READY IN 1911; Head of Hudson & Manhattan Road Promises It After the Board of Estimate Approves. BUSINESS MEN GRATIFIED Mr. McAdoo Also Happy -- He Will Begin at Once to Complete the Jersey-Grand Central Route". The New York Times. 1909-06-05. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ "MORGAN SYNDICATE TAKES M'ADOO NOTES; An Issue of $5,500,000 Put Out Through Harvey Fisk & Sons to Finish the Tubes". The New York Times. 1910-02-05. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ↑ "M'Adoo Tubes Now Reach 33rd Street; First Through Train from the Downtown Terminal to New One in the Shopping Belt". The New York Times. November 3, 1910. p. 11. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ "M'ADOO'S RAILROAD SLOW IN BUILDING; Two Months More Time Given for Extension to Grand Central". The New York Times. 1914-04-09. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ↑ "HUDSON TUBE ASKS DELAY.; Seventeenth Application for More Time to Extend Subway". The New York Times. February 16, 1920. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ "New Subway Routes in Hylan Program to Cost $186,046,000 – Board of Transportation Adopts 22.90 Miles of Additional Lines – Total Now $345,629,000 – But the Entire System Planned by Mayor Involves $700,000,000 – Description of Routes – Heaviest Expenditures Will Be Made on Tunnels – No Allowance for Equipment – New Subway Routes to Cost $186,046,000". The New York Times. 1925-03-21. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- ↑ "6TH AV. SUBWAY PLAN HINGES ON TUBES' USE; City Must Reach Agreement With Hudson & Manhattan to Carry Out Project". The New York Times. November 20, 1924. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ↑ "FINAL CONTRACTS TO FINISH SUBWAY AWARDED BY CITY; Include $20,000,000 for Cars, Equipment and Substations for Manhattan Line. OPERATION SET FOR 1931 Board of Transportation Moves to Rid Sixth Avenue of Trolley Tracks. SEEKS TO BUY FRANCHISE Line Willing to Exchange It for Bus Permit--Negotiations Pushed to Extend Tube". The New York Times. August 1, 1929. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ↑ "DELANEY FOR RAZING ELEVATED LINE NOW; Work in 6th Av. Could Begin in Six Months if Condemnation Started at Once, He Says. SEES CUT IN SUBWAY COST Eliminating Need for Underpinning Would Save $4,000,000 and Speed Construction, He Holds". The New York Times. January 11, 1930. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ "6th Av. Tube Work to be Begun Oct. 1". The New York Times. August 8, 1935. p. 23. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "New Subway Line on 6th Ave. Opens at Midnight Fete". The New York Times. December 15, 1940. pp. 1, 56. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Hudson Tube Terminus At 33d St. Closes Today". The New York Times. 1937-12-26. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ↑ "Hudson Tube Opens Terminal Today – Remodeled 33d St. Station Cost City $800,000 as Part of 6th Ave. Subway Expense – Closed for Two Years – Two Train Platforms and 3 Sets of Tracks Among New Transit Equipment". The New York Times. September 24, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Tube Terminal to Reopen – Station at 33d St. and 6th Ave. to Renew Service Sept. 24". The New York Times. September 12, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ↑ "GAY CROWDS ON LAST RIDE AS SIXTH AVE. ELEVATED ENDS 60-YEAR EXISTENCE; 350 POLICE ON DUTY But the Noisy Revelers Strip Cars in Hunt for Souvenirs SUIT MAY DELAY RAZING Little Threat Seen to Plan, However-Jobless Workers to Press Their Protest Makes Only One Stop Entrances Are Boarded Up FINAL TRAINS RUN ON ELEVATED LINE Police Guard Structure". The New York Times. 1938-12-05. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ↑ "H. & M. STATION TO CLOSE; State Authorizes Shutdown of Tube Line's 19th Street Stop". The New York Times. February 19, 1954. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Hudson Tubes Sale Is Approved by I.c.c." The New York Times. 1962-08-29. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ↑ Levey, Stanley (1961-04-19). "Construction of New IND Tunnel For 6th Ave. Line Begins Today; Express Tracks Deep Under Street to Run From 4th to 34th St. -- 1964 Finish Set for $22,000,000 Job". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ↑ Annual Report 1964–1965. New York City Transit Authority. 1965.

- 1 2 Levey, Stanley (1962-10-11). "Hudson Tubes Halt 33d St. Run; IND Digging Endangers Tunnel; SERVICE TO 33D ST. HALTED BY TUBES". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ↑ "Service Is Resumed By Hudson Tubes To 33d St. Terminal". The New York Times. 1962-10-15. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ↑ Perlmutter, Emanuel (November 27, 1967). "BMT-IND Changes Bewilder Many – Transit Authority Swamped With Calls From Riders as New System Starts". The New York Times. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Listings November 30, 2001". Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ↑ Karnoutsos, Carmela (2002). "Hudson & Manhattan Railroad Powerhouse". New Jersey City University. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

Further reading

- Walker, James Blaine (1918). "XX. The Hudson and Manhattan Tunnels Under the Hudson River". Fifty Years of Rapid Transit, 1864 to 1917. New York: Law Printing Co. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- Progress of the Great Railway Tunnels Under the Hudson River between New York and New Jersey City Scientific American, November 1, 1890