Bronx–Whitestone Bridge

| Bronx-Whitestone Bridge | |

|---|---|

View of the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge from Queens. | |

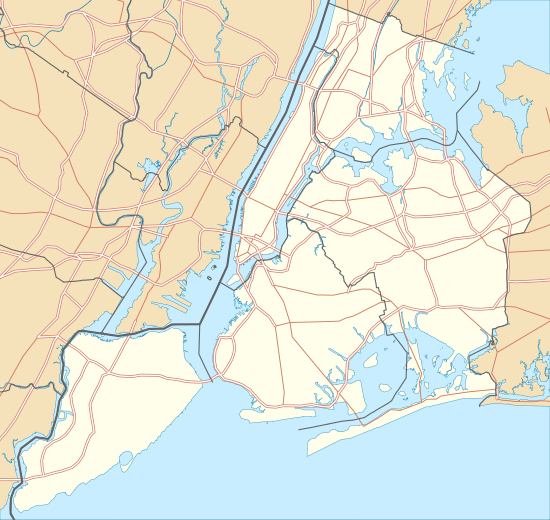

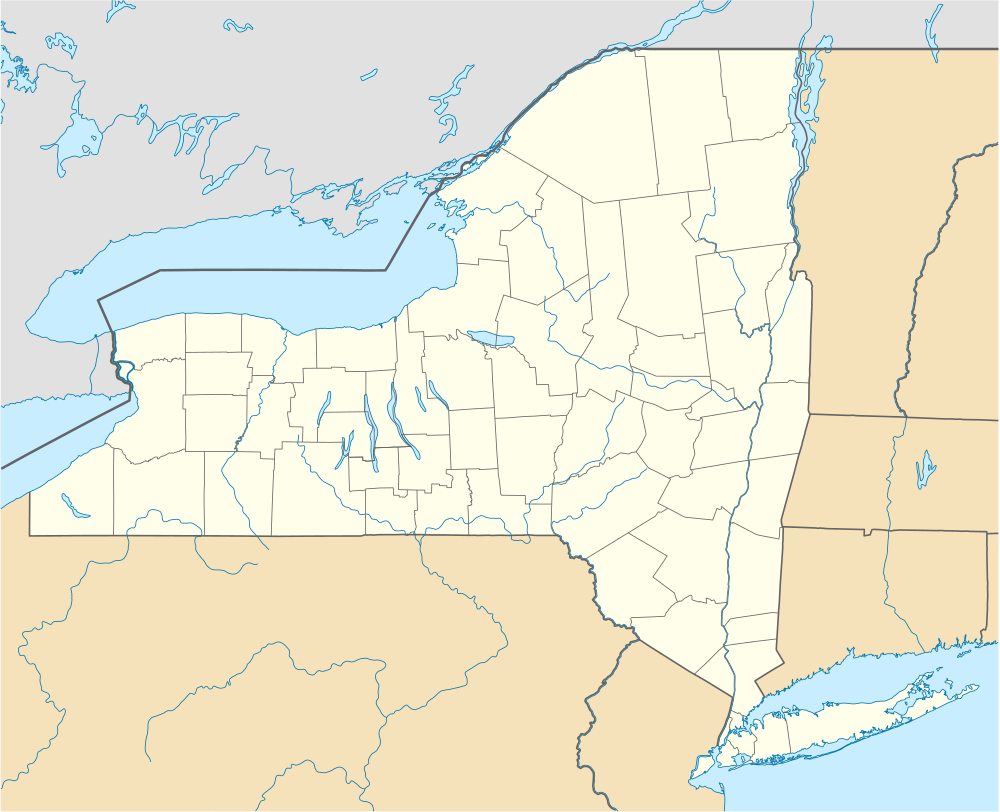

| Coordinates | 40°48′03″N 73°49′50″W / 40.80083°N 73.83056°WCoordinates: 40°48′03″N 73°49′50″W / 40.80083°N 73.83056°W |

| Carries |

6 lanes of |

| Crosses | East River |

| Locale | New York City (Throggs Neck, Bronx – Whitestone, Queens) |

| Other name(s) | Whitestone Bridge |

| Maintained by | MTA Bridges and Tunnels |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Suspension bridge |

| Total length | 3,770 feet (1,150 m) |

| Longest span | 2,300 feet (700 m) |

| Clearance above | 14 feet 6 inches (4.4 m) |

| Clearance below | 134 feet 10 inches (41.1 m) |

| History | |

| Construction cost | $17.5 million[1] |

| Opened | April 29, 1939 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 124,337 (2016)[2] |

| Toll | As of March 19, 2017, $8.50 (Tolls By Mail and non-New York E-ZPass); $5.76 (New York E-ZPass) |

Bronx-Whitestone Bridge  Bronx-Whitestone Bridge  Bronx-Whitestone Bridge | |

The Bronx–Whitestone Bridge (colloquially referred to as the Whitestone Bridge or simply the Whitestone) is a suspension bridge in New York City, carrying six lanes of Interstate 678 over the East River. The bridge connects Throggs Neck and Ferry Point Park in the Bronx with the Whitestone section of Queens.

The bridge was designed by Othmar Ammann and opened to traffic with four lanes on April 29, 1939.[3] The Bronx–Whitestone Bridge is owned by New York City and operated by the MTA Bridges and Tunnels, an affiliate agency of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

History

Planning

The idea for a crossing between the Bronx and Whitestone, Queens had come as early as 1905. At the time, residents around the proposed area of the bridge protested construction in fear of losing the then-rural character of the community. In 1929, however, the Regional Plan Association (RPA) had proposed another bridge from the Bronx to northern Queens to allow motorists from upstate New York and New England to reach Queens and Long Island without traveling through the traffic-ridden communities of western Queens.[4] On February 25, 1930, urban planner Robert Moses proposed a Ferry Point Park-to-Whitestone Bridge as part of his Belt Parkway system around Brooklyn and Queens.[5]

As the 1930s progressed, Moses found his bridge increasingly necessary to directly link the mainland to the 1939 New York World's Fair and to LaGuardia Airport (then known as North Beach Airport). In addition, the Whitestone Bridge was to provide congestion relief to the Triborough Bridge. It was said that the new bridge would also spur a wave of industrial development in the Bronx.[6] The RPA had also said that the Whitestone Bridge should have rail connections, or at least be able to accommodate them in the future, but the rail connections were not supported by Moses.

Construction

In 1936, Governor Herbert H. Lehman signed a bill that authorized the construction of the Bronx–Whitestone Bridge, which would connect Queens and the Bronx.[7] At its north end, the Bronx–Whitestone Bridge would connect to Eastern Boulevard (later known as Bruckner Boulevard) via the Hutchinson River Parkway.[8] At its south end, the bridge would connect to a new Whitestone Parkway, which led southwest off the bridge to Northern Boulevard.[8][9] Plans for the bridge were completed by February 1937, at which time the state started issuing bonds to fund bridge construction.[10] The Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority was to construct the span.[11] Moses argued that the TBTA and the city should each be responsible for half of the bridge's $17.5 million cost.[1]

The right-of-way for the Whitestone Bridge and Parkway was legally designated in July 1937.[12] Moses raised controversy when he quickly decided to demolish seventeen homes in the Queens community of Malba. He argued that such measures were necessary to complete the bridge on schedule.

Designer Othmar Ammann had several plans for the bridge that would keep construction on its tight schedule. The two 377-foot (115 m) towers were constructed in a short 18 days and were the first to have no diagonal cross bracing. Unlike other suspension bridges, the Whitestone Bridge did not have a stiffening truss system. Instead, 11-foot (3.4 m) I-beam girders gave the bridge an art deco streamlined appearance.

A $1.13 million contract for the construction of the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge's towers was awarded in June 1937 to the Bethlehem Steel Company.[13] The process of spinning the bridge's cables commenced in September 1938.[14] Construction on the bridge and the nearby Triborough Bridge was sped up so that they would be ready in time for the 1939 World's Fair.[15]

Opening

The Bronx–Whitestone Bridge opened on April 29, 1939, in festivities led by then-Mayor of New York City Fiorello H. La Guardia.[3] The bridge featured pedestrian walkways as well as four lanes of vehicular traffic, which carried 17,000 vehicles per day during the year 1940. The toll was 25 cents. The new "Whitestone" or Type 41 lamp post was later used in many other projects.[16] The 2,300-foot (700 m) center span was the fourth longest in the world at the opening. However, Ammann's plan to use I-beam girders proved to be a poor one after the collapse of the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington (known as Galloping Gertie for the effect wind had on the structure). The Bronx–Whitestone Bridge used the same general design as the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. The Narrows Bridge employed an 8-foot (2.4 m) deep girder system, much like the 11-foot (3.4 m) I-beam girders of the Whitestone Bridge. To mitigate the risk of failure from high winds, eight stay cables (two per tower per side) were installed for added stability in 1940.

Starting in 1943, the pedestrian walkways were removed from the bridge allowing for vehicular traffic expansion by the creation of two more vehicular lanes. The project's primary goal was to reinforce the bridge with trusses after the Tacoma Narrows Bridge disaster. The four lanes of roadway traffic were widened to six lanes and 14-foot (4.3 m) high steel trusses were installed on both sides of the deck to weigh down and stiffen the bridge in an effort to reduce oscillation. These trusses detracted from the former streamlined looking span but were later removed (see § Major repairs).

Originally built to connect the Hutchinson River Parkway in the Bronx to the Whitestone Parkway in Queens, the Bronx–Whitestone Bridge was redesignated as an interstate highway, Interstate 678, in the late 1950s. The approaches to the bridge were soon after converted to Interstate Highway standards. The Whitestone Parkway became the Whitestone Expressway, and the portion of the Hutchinson between the bridge and the Bruckner Interchange became the Hutchinson River Expressway. They now share the I-678 designation with the bridge itself.

Major repairs

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority planned to spend $286 million in bridge renovations, which started in August 2001. In 2003, the Metropolitan Transit Authority restored the classic lines of the bridge by removing the stiffening trusses and installing fiberglass fairing along both sides of the road deck. The lightweight fiberglass fairing is triangular in shape giving it an aerodynamic profile "that slices the wind as it passes over the bridge".[17][18] The removal of the trusses and other changes to the decking cut the bridge's weight by 6,000 tons, some 25% of the mass suspended by the cables.[19]

Other recent renovations include adding mass dampers to stabilize the bridge deck, repainting the two towers and the deck of the bridge, upgrading the lighting systems (including the beacons of the bridge and bulbs), and installing variable message signs. Replacing the deck of the bridge and assisting in lightening the deck by 6,000 tons was projected to be done by 2008.[20] The bridge remains in service during the overhaul, but a reduced number of lanes lead to traffic backups and signs suggesting use of the Throgs Neck Bridge. Trucks over 40 tons have been prohibited from using the span since 2005.

Other changes including a third supporting pier, the removal of the median barrier, the removal and replacement of the old roadway with a new superstructure, and demolition of the old supporting piers are being undertaken at a cost of $192.8 million.[21] The Queens and Bronx approaches were replaced in a project that started in 2008[22] and ended in 2015.[23]

Tolls

As of March 19, 2017, drivers pay $8.50 per car or $3.50 per motorcycle for tolls by mail. E‑ZPass users with transponders issued by the New York E‑ZPass Customer Service Center pay $5.76 per car or $2.51 per motorcycle. All E-ZPass users with transponders not issued by the New York E-ZPass CSC will be required to pay Toll-by-mail rates.[24]

Open-road cashless tolling began on September 30, 2017.[25] The tollbooths were gradually dismantled, and drivers are no longer able to pay cash at the bridge. Instead, there are cameras mounted onto new overhead gantries near where the booths are currently located.[26][27] Drivers without E-ZPass will have a picture of their license plate taken, and the toll will be mailed to them. For E-ZPass users, sensors will detect their transponders wirelessly.[26][27]

Public transportation

The bridge carries two MTA Regional Bus Operations routes, the Q44 SBS, operated by MTA New York City Transit, and the Q50 Limited (formerly part of the QBx1), operated by the MTA Bus Company.[28]

After the removal of the sidewalks starting in 1943, bicyclists were able to use QBx1 buses of the Queens Surface Corporation, which could carry bicycles on the front-mounted bike racks. However, since the Metropolitan Transportation Authority absorbed the bus routes formerly operated by Queens Surface, the bike racks were eliminated.[29] In April 1994, bike racks were installed onto QBx1 buses,[30] but the bike-on-bus program was eliminated on February 27, 2005, the same day as the MTA's takeover of the QBx1 route.[31] After the QBx1 was replaced by the Q50, the MTA reintroduced bike racks on Q50 buses in spring 2018.[32]

Road connections

The Bronx–Whitestone Bridge carries I-678 across the East River. From the Queens side, the Whitestone Expressway carries I-678 to the bridgehead. The Cross Island Parkway intersects with the Whitestone Expressway 0.6 miles (0.97 km) before the bridge.

On the Bronx side, the bridge leads to the Bruckner Interchange, which serves as the northern terminus of I-678, which is where the Cross Bronx Expressway (I-95 and I-295), Bruckner Expressway (I-278 & I-95), and the Hutchinson River Parkway meet.

See also

- Lists of crossings of the East River

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in New York

References

- 1 2 "WHITESTONE BRIDGE PLAN; Moses Tells How He Thinks the $17,500,000 Cost Should Be Split" (PDF). The New York Times. April 23, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ "New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes" (PDF). New York City Department of Transportation. 2016. p. 11. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- 1 2 "WHITESTONE SPAN OPENED BY MAYOR; New Bronx-Long Island Link Hailed as Symbol of City's Never-Ending Progress". The New York Times. April 30, 1939. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ↑ "Highway Loop in Plan Skirts Busy Centers". The New York Times. May 30, 1929. p. 12. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ↑ "ASKS NEW CITY PARKS TO COST $20,000,000; Metropolitan Conference Urges Prompt Purchases, Chiefly in Queens and Richmond. BERRY GETS HONOR SCROLL Calls for a 'Normal' Pace in Public Projects and Predicts Agency to Coordinate Them" (PDF). The New York Times. February 26, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ "NEW BRONX BRIDGE WILL AID INDUSTRY; Benefits of Whitestone Span to Borough Are Outlined by Roderick Stevens" (PDF). The New York Times. March 21, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ "LEHMAN SIGNS BILL FOR RELIEF BONDS; Measure Authorizing Referendum on $30,000,000 Issue Is One of Many Approved. HE MAKES PLEA TO VOTERS Whitestone Bridge Plan Ratified – Increased Fees for City Marshals Is Vetoed" (PDF). The New York Times. May 21, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- 1 2 New York (Map). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1940.

- ↑ New York with Pictorial Guide (Map). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1942.

- ↑ "WHITESTONE BRIDGE AT FINANCING STAGE; Authority Scans Two Plans for a Bond Issue to Build Bronx-Queens Span" (PDF). The New York Times. February 15, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ "LEHMAN -SIGNS BRIDGE BILL; Triborough and Whitestone Spans Put Under Joint Authority" (PDF). The New York Times. 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ "CITY GETS QUEENS LAND; 2 1/2-Mile Strip Being Taken for Link to Whitestone Bridge" (PDF). The New York Times. July 22, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ "TOWER CONTRACT LET FOR WHITESTONE SPAN; Triborough Authority Awards Work to American Bridge Company at $1,128,800" (PDF). The New York Times. June 24, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ "SPINNING OF CABLES ON NEW SPAN BEGUN.; Moses, Leading Inspection Party, Gives Signal to Start Wire-Twisting Process TASK TO TAKE 3 MONTHS Crews of 100 at Each End of Bronx-Whitestone Bridge to Create Huge Ropes Spinner Carries First Wire $13,000,000 for Highways" (PDF). The New York Times. September 15, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ "NEW BRIDGES TIED IN; Work Is Speeded on Traffic Links With Whitestone and Triborough Spans" (PDF). The New York Times. February 26, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ Walsh, Kevin (August 1, 2013). "Whitestone Lamps". Greater Astoria Historic Society. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ "A New Look for a Classic Bridge". MTA Newsroom, Bridges & Tunnels. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved November 2, 2007.

- ↑ Roth, Alisa (October 12, 2003). "A Onetime Thing of Beauty Gets a Little Prettying Up". The New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ Chan, Sewell (February 18, 2005). "A Bridge Too Fat". The New York Times. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ↑ Preliminary Capital Program for 2005–2009, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, dated July 29, 2004.

- ↑ , MTA Bridges and Tunnels Construction Improvements

- ↑ "Bronx-Whitestone Bridge approach upgrade". Bronx Times. December 5, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Press Release - Bridges & Tunnels - Bronx-Whitestone Queens Approach Reconstruction Project Completed With Reopening of Third Avenue Exit". MTA. May 8, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ↑ "2017 Toll Information". MTA Bridges & Tunnels. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Castillo, Alfonso A. (October 2, 2017). "Cashless tolling arrives at all MTA bridges". Newsday. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- 1 2 Siff, Andrew (October 5, 2016). "Automatic Tolls to Replace Gates at 9 NYC Spans: Cuomo". NBC New York. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- 1 2 WABC (December 21, 2016). "MTA rolls out cashless toll schedule for bridges, tunnels". ABC7 New York. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Queens Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. December 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Bronx-Whitestone Bridge (I-678)". Transportation Alternatives. Section 4-04(e)(2). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2008. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ "New York City Bicycle Master Plan" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Transportation, New York City Department of City Planning. May 1997. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ↑ "The New York City Bicycle Survey: A Report Based on the Online Public Opinion Questionnaire Conducted for Bike Month 2006" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. May 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016.

- ↑ "MTA Running Bus Routes with New Bike Racks This Summer". www.mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bronx-Whitestone Bridge. |

- Official website

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NY-308, "Bronx-Whitestone Bridge, Spanning East River between Whitestone, Queens & the Bronx, Bronx County, NY", 11 photos, 1 photo caption page

- NYCRoads.com Bronx-Whitestone Bridge

- Bronx-Whitestone Bridge at Structurae