PATH (rail system)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A PATH train of PA5 cars on the Newark–World Trade Center line, crossing the Passaic River en route to the World Trade Center | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Newark/Hudson County, New Jersey and Manhattan, New York | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of lines | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of stations | 13 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership | 283,719 (2017; weekdays)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Annual ridership | 82,812,915 (2017)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Began operation |

February 25, 1908 (as H&M Railroad) September 1, 1962 (as PATH) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of vehicles | 350 PA5 cars[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System length | 13.8 mi (22.2 km) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 600 V (DC) Third Rail | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) is a rapid transit system serving Newark, Harrison, Hoboken, and Jersey City in metropolitan northern New Jersey, as well as lower and midtown Manhattan in New York City. The PATH is operated by the Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. PATH trains run 24 hours a day and 7 days a week, with four lines during the daytime on weekdays and two lines during weekends and late nights.

The system has a total route length of 13.8 miles (22.2 km), not double-counting route overlaps. PATH trains use tunnels in Manhattan, Hoboken, and downtown Jersey City. The tracks cross the Hudson River through century-old cast iron tubes that rest on the river bottom under a thin layer of silt. The PATH tracks from Grove Street in Jersey City west to Newark Penn Station run in open cuts, at grade level, and on elevated track.

The routes of the PATH system were originally operated by the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (H&M). The railroad's Uptown Hudson Tubes first opened in 1908, followed by the Downtown Hudson Tubes in 1909, and the system was completed by 1911, with 16 stations. The H&M system had reached its peak in 1927, with 113 million passengers, and soon started to decline with the advent of vehicular travel. In 1937, two new stations in Harrison and Newark were built, replacing three existing stations. Two other stations in Manhattan were closed in the mid-20th century. The H&M went into bankruptcy in 1954. It operated under bankruptcy protection until 1962, when the Port Authority took it over and renamed it PATH. In 1971, as part of the construction of the World Trade Center, the Hudson Terminal in Lower Manhattan was replaced by the World Trade Center station. The PATH system was disrupted for several years after the World Trade Center was destroyed on September 11, 2001, and a new transport hub was eventually built at the site of the World Trade Center station.

There have been several unfulfilled proposals to extend the H&M and later the PATH, including to Grand Central Terminal and Astor Place in New York City and to Plainfield, New Jersey. A PATH extension to Newark Airport, first proposed in the 1970s, was reconsidered in the 2000s and is projected to start construction in 2020.

PATH accepts the same pay-per-ride MetroCard used by the New York City Transit system, but it does not accept unlimited ride, reduced fare, or EasyPay MetroCards. The PATH fare is also payable using a smart card called SmartLink, which is not compatible with any other transit system. In 2017, PATH had an annual ridership of 82.8 million passengers, with an average daily ridership of 283,719.

The PATH system is technically a commuter railroad under the jurisdiction of the Federal Railroad Administration, even though it operates as a rapid transit system. This is because its predecessor, the H&M, used to share its route to Newark with the Pennsylvania Railroad. The PATH uses one class of rolling stock, the PA5, which was delivered in 2009–2011.

History

Hudson & Manhattan Railroad

The PATH predates the New York City Subway's first underground line, operated by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company. It was originally known as the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (H&M). Although the railroad was first planned in 1874, existing technologies could not safely tunnel under the Hudson River. Construction began on the existing tunnels in 1890, but stopped shortly thereafter when funding ran out. Construction resumed in 1900 under the direction of William Gibbs McAdoo, an ambitious young lawyer who had moved to New York from Chattanooga, Tennessee. McAdoo later became president of the H&M.[3] The H&M became so closely associated with McAdoo that, in its early years, they became known as the McAdoo Tubes or McAdoo Tunnels.[4][5]

Construction

The first tunnel, now called the Uptown Hudson Tubes, started construction in 1873.[6]:14 The chief engineer of the time, Dewitt Haskin, tried to construct the tunnel using compressed air and then line it with brick.[3] The workers succeeded in building the tunnel out by approximately 1,200 feet (366 m) from Jersey City.[7]:12 However, construction was disrupted by a lawsuit,[8] as well as a series of blowouts, including a particularly serious one in 1880 that killed 20 workers.[9] The project was abandoned in 1883 due to a lack of funds.[3][6]:67[7]:12 Another effort by a British company, between 1888 and 1892, also proved to be unsuccessful.[10]

_(cropped).jpg)

When the New York and Jersey Tunnel Company resumed construction on the uptown tubes in 1902, chief engineer Charles M. Jacobs employed a different method of tunneling. He pushed a shield through the mud and then placed tubular cast iron plating around the tube.[3] As the northern tube of the uptown tunnel was completed shortly after the resumption of construction,[11] the southern tube was constructed using the tubular cast iron method.[3][12] Construction of the uptown tunnel was completed in 1906.[13]

By the end of 1904, the New York and Jersey Railroad Company had received permission from the New York City Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners to build a new subway line through Midtown Manhattan, which would connect with the Uptown Hudson Tubes; the company received the sole rights to operate this line for a duration of 25 years. The Midtown Manhattan line would travel eastward under Christopher Street before turning northeastward under Sixth Avenue, then continue underneath Sixth Avenue to a terminus at 33rd Street.[14]

In January 1905, the Hudson Companies was incorporated for the purpose of completing the Uptown Hudson Tubes and constructing the Sixth Avenue line. The company, which was contracted to construct the Uptown Hudson Tubes' subway tunnel connections on each side of the river, already had a capital of $21 million.[15] The H&M was incorporated in December 1906 to operate a passenger railroad system between New York and New Jersey via the Uptown and Downtown Tubes.[16][17]

A second pair of tunnels, the current Downtown Hudson Tubes, was built about 1 1⁄4 miles (2.0 km) south of the first pair. Construction began in 1906 and was completed in 1909, also using the tubular cast iron method.[3][7]:18 The uptown and downtown tunnels both consisted of two tubes, which each contained a single unidirectional track.[18] The eastern ends of the tunnels, located underneath Manhattan, employed cut and cover construction methods.[19]

Opening

_Newark.tiff.png)

Test runs of trains without passengers started through the tunnels in late 1907.[20] Revenue service started between Hoboken Terminal and 19th Street at midnight on February 26, 1908, after President Theodore Roosevelt pressed a button at the White House that turned on the electric lines in the uptown tubes; the "official" first train had occurred the previous day, but was open only to selected officials.[21][7]:21 This became part of the current Hoboken–33rd Street line.[22]:2 The H&M system was powered by a 650-volt direct current third rail, which in turn drew power from an 11,000-volt transmission system with three substations. The substations were the Jersey City Powerhouse, as well as two smaller substations at the Christopher Street and Hudson Terminal stations.[23]

An extension of H&M from 19th Street to 23rd Street opened on June 15, 1908.[24] On July 19, 1909, service began between the Hudson Terminal in Lower Manhattan and Exchange Place in Jersey City, through the downtown tubes.[25] The connection between Exchange Place and the junction near Hoboken Terminal opened on August 2, 1909,[26] and trains started running on the Hoboken–Hudson Terminal line.[22]:3 A new line running between 23rd Street and Hudson Terminal was created on September 20, 1909.[22]:3 On September 6, 1910, the H&M was extended from Exchange Place west to Grove Street,[27] and the 23rd Street–Hudson Terminal line was rerouted to Grove Street, becoming part of the current Journal Square–33rd Street line. A fourth line, Grove Street–Hudson Terminal (now the Newark–World Trade Center line), was also created.[22]:3 On November 10 of that year, the Hoboken-23rd Street and Grove Street-23rd Street lines were extended from 23rd Street to 33rd Street.[28][29]

The H&M's Grove Street–Hudson Terminal line was extended west from Grove Street to Manhattan Transfer on October 1, 1911,[30] and then to Park Place in Newark on November 26 of that year.[31] After completion of the uptown Manhattan extension to 33rd Street and the westward extension to the now-defunct Manhattan Transfer and Park Place Newark terminus in 1911, the H&M's track mileage had essentially been fully built.[32]:7 The final cost was estimated at $55–$60 million ($1,498,000,000 to $1,634,000,000 today).[33][34] A stop at Summit Avenue (now Journal Square), located between Grove Street and Manhattan Transfer, opened on April 14, 1912, as an infill station on the Newark-Hudson Terminal line, though only one platform was in use at the time. The Summit Avenue station was completed on February 23, 1913, allowing service from 33rd Street to terminate there.[32][22]:7 The last station, at Harrison, opened on March 6, 1913.[32]

External relations and unbuilt expansions

Originally, the Hudson Tubes were designed to link three of the major railroad terminals on the Hudson River in New Jersey—the Erie Railroad (Erie) and Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) in Jersey City and the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad (DL&W) in Hoboken—with New York City. While PATH still provides a connection to train stations in Hoboken and Newark, the Erie's Pavonia Terminal at what is now Newport and the PRR terminal at Exchange Place station were both eventually closed and subsequently demolished. There were early negotiations for New York Penn Station to also be shared by the two railroads.[35] In 1908, McAdoo proposed to build an additional branch of the H&M southward to Communipaw, so that there would be a transfer to the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal there.[36]

When the New York City Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners had approved the construction of the H&M's Sixth Avenue line in 1904, it also left open the option of digging an east-west crosstown line. The New York and Jersey Railroad Company was given the perpetual rights to dig under Christopher and Ninth Streets eastward to either Second Avenue or Astor Place.[14][7]:22 This option was never fully exercised, as the crosstown line was only dug about 250 feet (76 m); the partly completed crosstown tube still exists.[7]:22[3]

There were also plans to extend the H&M's Uptown Tubes northeast to Grand Central Terminal, located at Park Avenue and 42nd Street.[37] These plans were first announced in February 1909, and the openings of the 28th and 33rd Street stations were delayed because of planning for the Grand Central extension.[38] The New York Times speculated that the downtown tunnels would see more passenger use than the uptown tunnels because, at the time, the city's financial core was located downtown rather than in midtown. The Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) was a viable competitor to the H&M, as its Lexington Avenue line was proposed to connect to the H&M at Grand Central, Astor Place, and Fulton Street–Hudson Terminal once the planned system was complete.[37] Its terminus at Grand Central was supposed to be located directly below the IRT's 42nd Street line but above the IRT's Steinway Tunnel to Queens. However, the IRT constructed an unauthorized ventilation shaft between its two levels in an effort to force the H&M to build its station at a very low depth, thus making it harder for any passengers to access the H&M station.[39] As an alternative, it was proposed to connect the Uptown Tubes to the Steinway Tunnel.[40] A franchise to extend the Uptown Tubes to Grand Central was awarded in June 1909.[41] By 1914, the H&M had not started construction of the Grand Central extension yet, and it wished to delay the start of construction further.[42][7]:55 By 1920, the H&M had submitted seventeen applications in which they sought to delay construction of the extensions; in all seventeen instances, the H&M had claimed that it was not an appropriate time to construct the tube.[43] This time, however, the Rapid Transit Commissioners declined this request for a delay, effectively ending the H&M's right to build an extension to Grand Central.[7]:55–56

In September 1910, McAdoo proposed another expansion, consisting of a second north-south line through Midtown Manhattan. The line's southern terminus would be located at Hudson Terminal, and its northern terminus would be at 33rd Street and Sixth Avenue, underneath Herald Square and near the H&M's existing 33rd Street station. The new north-south line, which would be 4 miles (6.4 km) long, would run mainly under Broadway, although a small section of the line near Hudson Terminal would run under Church Street. Under McAdoo's plan, the city could take ownership of this line within 25 years of its completion.[28] That November, McAdoo also proposed that the two-track Broadway line be tied into the IRT's original subway line in Lower Manhattan. The Broadway line, going southbound, would merge with the local tracks of the IRT's Lexington Avenue line in the southbound direction at 10th Street. A spur off the Lexington Avenue line in Lower Manhattan, in the back of Trinity Church, would split eastward under Wall Street, cross the East River to Brooklyn, then head down Fourth Avenue in Brooklyn, with another spur underneath Lafayette Avenue. McAdoo wanted not only to operate what was then called the "Triborough System", but also the chance to bid on the Fourth Avenue line in the future.[44] The franchise for the Broadway line was ultimately awarded to the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) in 1913, as part of the Dual Contracts.[45][46] The first section of the BRT's Broadway line opened in 1917,[47] and that line was completed by 1920.[48] The BRT was also given the franchise for the Fourth Avenue line in Brooklyn as part of the Dual Contracts.[49] The BRT's Fourth Avenue line opened in stages from 1915[50] to 1925.[51][52]

In 1909, McAdoo considered extending the H&M in New Jersey, building a branch north to Montclair and Essex County. A route extending north from Newark would continue straight to East Orange. From there, branches would split to South Orange in the south and Montclair in the north.[53]

Start of decline

The H&M saw record ridership in 1927, when 113 million people used the system.[7]:55 The opening of the Holland Tunnel that year, coupled with the Depression that began shortly after, began the decline of H&M.[7]:55[54] The later construction of the George Washington Bridge in 1931 and the Lincoln Tunnel in 1937 further enticed people away from the railroad, since these former passengers were now able to cross the Hudson River in buses and personal cars.[7]:56[55] The Summit Avenue station was renovated and rededicated as "Journal Square" in 1929, and the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Powerhouse in Jersey City shut down later the same year, as the H&M system could now draw energy from the greater power grid.[32]:7

In the 1930s, service to the Uptown Hudson Tubes in Manhattan was affected due to the construction of the Independent Subway System (IND)'s Sixth Avenue Line. The 33rd Street terminal closed on December 26, 1937 and service on the H&M was cut back to 28th Street to allow for construction on the subway to take place.[56] The 33rd Street terminal was moved south to 32nd Street and reopened on September 24, 1939. The city had to pay $800,000 to build the new 33rd Street station and reimbursed H&M another $300,000 to the H&M for the loss of revenue.[57] The 28th Street station was closed at this time because the southern entrances to the 33rd Street terminal were located only two blocks away, rendering the 28th Street stop unnecessary. It was demolished to make room for the IND tracks below.[58]

The Manhattan Transfer station was closed on June 20, 1937, and H&M was realigned to Newark Penn Station from the Park Place terminus a quarter-mile north; the Harrison station across the Passaic River was moved several blocks south as a result. On the same day, the Newark City Subway was extended to Newark Penn Station. The upper level of the Centre Street Bridge to Park Place later became Route 158.[59]

Promotions and other advertising proved ineffectual at slowing the financial decline of the H&M. The 19th Street station in Manhattan was closed in 1954.[60] The same year, the H&M entered receivership due to a consistent loss of revenue.[61] It operated under bankruptcy protection for years and received a tax cut in 1956.[62] That year, the H&M saw 37 million annual passengers, and transportation experts called for subsidies to help keep H&M solvent. One expert proposed making a "rail loop", with the Uptown Hudson Tubes connecting to the IND Sixth Avenue Line, then continuing up Sixth Avenue and west via a new tunnel to Weehawken, New Jersey.[63] By 1958, the H&M recorded 30.46 million annual passengers.[55] Two years later, creditors approved a tax plan to reorganize the company.[64] During this time, H&M workers went on strike twice due to wage disputes: in 1953 for two days,[65] and in 1957 for a month.[66]

Port Authority operation

Takeover

_(26080894656).jpg)

The planning of the World Trade Center in the early 1960s enabled a compromise between the Port Authority and the states of New York and New Jersey. The Port Authority agreed to purchase and maintain the Tubes in return for the rights to build the World Trade Center on the land occupied by H&M's Hudson Terminal, which was the Lower Manhattan terminus of the Tubes.[67] A formal agreement was made in January 1962.[68] On April 1 of the same year, the Port Authority set up two subsidiary corporations: the Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation (PATH) to operate the H&M tubes, as well as another subsidiary to operate the World Trade Center. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey would have been bound under federal Interstate Commerce Commission rules if it ran the trains directly, but with the creation of the PATH Corporation, only the subsidiary's operations would be federally regulated.[69]

On September 1, 1962, PATH formally took over operation of the H&M Railroad and the Tubes.[7]:58[70] Upon taking over the H&M Railroad, the Port Authority spent $70 million to modernize its infrastructure.[71] The Port Authority also repainted H&M stations into the new PATH livery.[72] In 1964, the Port Authority ordered 162 PA1 railway cars to replace the H&M rolling stock.[73] The first PA1 cars were delivered in 1965.[74] Subsequently, the agency ordered 44 PA2 cars in 1967 and 46 PA3 cars in 1972.[75]

1970s

The Hudson Terminal was located on the future site of the World Trade Center. As part of the World Trade Center's construction, the Port Authority decided to demolish the Hudson Terminal and construct a new World Trade Center Terminal on the site.[68] Groundbreaking on the World Trade Center took place in 1966.[76] During excavation and construction, the original Downtown Hudson Tubes remained in service as elevated tunnels.[77] The new World Trade Center Terminal was opened on July 6, 1971, at a different location from the original Hudson Terminal.[78] The new station cost $35 million to build, and saw 85,000 daily passengers at the time of its opening.[79] At this time, the Hudson Terminal was shut down.[80]

.jpg)

In January 1973, the Port Authority released plans to double the size of the PATH system.[75] The plan called for a 15-mile (24 km) extension of the Newark–World Trade Center line from Newark Penn Station to Plainfield, New Jersey. A stop at Elizabeth would allow the PATH to serve Newark Airport as well. At the Newark Airport stop, there would be a transfer to a people mover to the terminals themselves.[81] Preliminary studies of the right-of-way, as well as a design contract, were conducted that year.[82] This 15-mile (24 km) extension was approved in 1975.[83] However, the Federal Urban Mass Transit Administration was wary of the proposed extension's usefulness and was reluctant to give the $322 million in funds that the Port Authority had requested for the project, which represented about 80% of the projected cost at the time.[84] Eventually, the administration agreed to back the PATH extension.[85] However, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Port Authority's use of bonds to finance the extension was not permitted, significantly setting back the project.[86] In June 1978, the extension, then estimated to cost $600 million, was canceled completely in favor of improved bus service in New Jersey.[87]

Also in 1973, PATH workers went on strike due to union disagreements with the Port Authority.[88] A strike had been avoided in January 1973,[89] but talks subsequently failed and workers walked out that April 1.[88] The 1973 strike had been caused by a dispute over salary increases that the Port Authority was unwilling to grant.[90] Negotiations between workers and the Port Authority broke down as the strike extended past one month.[91] The strike ended on June 2, 1973, sixty-three days after it had begun.[92]

The 1980 New York City transit strike suspended transit service on the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA)'s bus and subway routes from April 1 to 11. A special PATH route ran from 33rd Street to World Trade Center via Midtown Manhattan, Pavonia–Newport, and Exchange Place during the NYCTA strike.[93] PATH motormen also threatened to go on strike during this time, but this was unrelated to the NYCTA strike. The special service was suspended during April 8, a Tuesday, because some workers refused to voluntarily operate trains during their overtime hours.[94] On June 12, 1980, PATH workers again went on strike for the same reason as in 1973.[95] The 1980 strike, the first since 1973, continued for 81 days. During the strike, moisture built up within the tunnels and rust accumulated on the tracks, although the pumps in the underwater tunnels were still operating so that the tubes would not be flooded completely.[96] Alternative service across the Hudson River was provided by shuttle buses through the Holland Tunnel, though it was described as "inadequate".[97] The 1980 strike, which ended on September 1,[96] was the longest in the PATH's history.[98]

1980s and 1990s

During the 1980s, the PATH system experienced substantial growth in ridership, which meant the infrastructure needed expansion and rehabilitation. The Port Authority announced a plan in 1988 to upgrade the infrastructure so that stations on the Newark–WTC line could accommodate longer 8-car trains while 7-car trains could operate between Journal Square and 33rd Street.[99] In August 1990, the Port Authority put forth a $1 billion plan to renovate the PATH stations and add new rail cars.[100] To help provide revenue, the Port Authority installed video monitors in its stations that display advertising.[101] At that time, the Port Authority incurred a $135 million deficit annually, which it sought to alleviate with a fare hike to reduce the per passenger subsidy.[102] By 1992, the Port Authority had spent $900 million on infrastructure improvements, including repairing tracks; modernizing communications and signaling; replacing ventilation equipment; and installing elevators at seven stations as part of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.[103]

A new car maintenance facility was also added in Harrison, at a cost of $225 million, and opened circa 1990. On October 12, 1990, PATH's old Henderson Street Yard–a below-grade, open-air train storage yard at the northeast corner of Marin Boulevard and Christopher Columbus Drive just east of the Grove Street station–was closed.[104]

On December 11, 1992, a coastal storm caused high tides, which led to extensive flooding in the PATH tunnels. Most trains were stopped before reaching the floodwaters, but one train became stalled near Hoboken Terminal.[105] A 2,500–3,000-foot (760–910 m) section of track between Hoboken and Pavonia was flooded, as were other locations within the system. Some water pumps within the PATH system failed because there was too much water entering the system at once.[106] The Newark–World Trade Center service was not disrupted in the aftermath of the flood, but the Journal Square–33rd Street service was forced to slow down because several spots along the route needed to be pumped out.[105] Service to Hoboken was suspended for ten days, the longest period of disruption since the summer 1980 strike.[106]

When the World Trade Center bombing occurred on February 26, 1993, a section of ceiling in the PATH station collapsed and trapped dozens.[107][108] Nonetheless, the PATH station did not suffer any structural damage.[109] Within three days, the Port Authority was able to resume PATH service to the World Trade Center.[110]

In the summer of 1993, the Port Authority banned tobacco advertisements in all trains and stations. The Port Authority had earned $161,000 from these advertisements in the previous year.[111] A new car wash for the train cars opened in mid-September 1993 in Jersey City, replacing the old wash on Track 1 at the 33rd Street terminal. The new wash was computer-operated, and was designed to reclean and recycle the water used in the operation. More space for the operation was provided at Jersey City, allowing the detergent used on the cars to have more time to take effect. At 33rd Street, brushes began scrubbing the cars very soon after the detergent went on. The new facility was designed to give about a minute to allow the detergent to work, helping better clean the cars. The project allowed the Port Authority to deactivate the car wash at 33rd Street, providing more flexibility in terminal operations at the station.[112]

In April 1994, a new entrance to the Exchange Place was opened making the station ADA accessible. The new entrance was glass-enclosed and featured two elevators which led to a lower-level passageway 63 feet (19 m) down, from where another elevator went down the short distance to platform level.[113]

On April 29, 1996, three trains began running express on the Newark–World Trade Center service for six months, cutting running time by 3.5 minutes.[114] Weekend Hoboken–World Trade Center service began on October 27, 1996 on a six-month trial basis, and express Newark–World Trade Center service was made permanent the same day.[115][116]

September 11, 2001, and recovery

The World Trade Center station in Lower Manhattan, under the World Trade Center, is one of PATH's two New York terminals. The first station at the site, which replaced the old Hudson Terminal at the same place in 1971, was destroyed during the September 11 attacks, when the Twin Towers above it collapsed. Just prior to the collapse, the station was closed and any passengers in the station were evacuated.[7]:107

With the World Trade Center station destroyed, service to Lower Manhattan was suspended indefinitely.[117] Exchange Place, the next-to-last station before World Trade Center, was closed as well because it could not operate as a terminal station; the tracks could not turn back trains into the opposite direction.[118] The Exchange Place station also suffered severe water damage during the attacks.[119] A temporary PATH terminal at the World Trade Center was approved in December 2001 and was set to open within two years of that date.[120]

Shortly after the September 11 attacks, the Port Authority started operating two uptown services (Newark–33rd Street, colored red on the map, and Hoboken–33rd Street, colored blue),[121][122] and one intrastate New Jersey service (Hoboken–Journal Square, colored green).[123][122] One nighttime service was instituted: Newark–33rd Street (via Hoboken), colored red-and-blue.[122] In the meantime, modifications were made to a stub end tunnel to allow trains from Newark to reach the Hoboken bound tunnel and vice versa. The modifications required PATH to bore through the bedrock dividing the stub tunnel and the tunnels to and from Newark. This tunnel was known as the Penn Pocket, originally built for short turn World Trade Center to Exchange Place runs to handle PRR commuters from Harborside Terminal.[124] The new Exchange Place station opened on June 29, 2003.[119] Because of the original alignment of the tracks, trains to/from Hoboken used separate tunnels from the Newark service. Eastbound trains from Newark crossed over to the westbound track just west of Exchange Place. Trains then reversed direction and used a crossover switch to go to Hoboken. Eastbound trains from Hoboken entered on the eastbound track at Exchange Place. The train then reversed direction and used the same crossover switch to go to the westbound track to Newark before entering Grove Street.[7]:108

PATH service to Lower Manhattan was restored when a new, $323 million second station opened on November 23, 2003; the inaugural train was the same one that had been used for the evacuation.[125][7]:108–110 The second, temporary station contained portions of the original station, but did not have heating or air conditioning systems installed. The temporary entrance was closed on July 1, 2007, and demolished to make way for the third, permanent station; around the same time, the Church Street entrance opened.[126] A new entrance on Vesey Street opened in March 2008, and the entrance on Church Street was then demolished.[127]

On July 7, 2006, an alleged plot to detonate explosives in the PATH's Downtown Hudson Tubes (initially said to be a plot to bomb the Holland Tunnel) was uncovered by the FBI. According to officials, this plan was unsound due to the strength of both tunnels, as well as various restrictions in both the Holland Tunnel and the PATH system. Of the eight planners based in six different countries, three were arrested.[128]

Hurricane Sandy

At 12:01 am on October 29, 2012, PATH service was suspended system-wide in advance of Hurricane Sandy. The following day, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie stated that PATH train service would be out for 7–10 days as a result of the damage caused by the hurricane.[129] Storm surge from the hurricane caused significant flooding to PATH train stations in Hoboken and Jersey City, as well as at the World Trade Center.[129] An image captured from a PATH security camera showing the ingress of water at Hoboken at 8:23 p.m. on October 29, quickly spread across the Internet and became one of several representative images from the hurricane.[130]

The first revenue PATH trains after the hurricane were the Journal Square–33rd Street service, which recommenced on November 6 and ran only during the daytime.[131] Service was extended west to Harrison and Newark on November 12, in place of the Newark–World Trade Center service. Christopher Street and 9th Street were reopened during the weekend of November 17–18, but remained closed for the following five weekdays.[132] Normal weekday service on the Newark–World Trade Center and Journal Square–33rd Street lines resumed on November 26. On weekends, trains operated using the Newark–33rd Street service pattern.[133]

The Hoboken station suffered major damage after as much as eight feet (2.4 m) of water submerged the tunnels, and had to stay closed for several weeks for $300 million worth of renovations.[134] The Newark–33rd Street route was suspended for two weekends in mid-December, with the Newark–World Trade Center running in its place, in order to expedite the return of Hoboken service.[135] As a result, Hoboken Terminal reopened on December 19 for weekday daytime Hoboken–33rd Street service,[136] followed by the resumption of weekday 24-hour PATH service on January 9, 2013.[137][138] The Hoboken–World Trade Center trains resumed on January 29, and the pre-Hurricane Sandy service patterns were restored by the weekend of March 1.[139][140]

2010s improvements

The construction of the permanent four-platform World Trade Center Transportation Hub started in July 2008, when the first prefabricated "ribs" for the pedestrian walkway under Fulton Street were installed on the site.[141] Platform A, the first platform of the permanent station, opened February 25, 2014, serving Hoboken-bound riders.[142] Platform B and the remaining half of Platform A opened a year later on May 7, 2015.[143][144] The Oculus headhouse partially opened to the public on March 3, 2016, marking the opening of the hub.[145][146][147] Platforms C and D, the last two platforms in the station, were opened on September 8 of that year.[148][144]

In January 2010, Siemens announced that PATH would be spending $321 million to upgrade its signal system to use communications-based train control (CBTC), using Siemens' Trainguard MT CBTC, to accommodate anticipated growth in ridership.[149] The CBTC system would replace a fixed-block signaling system, which involved signals placed beside the track and was four decades old at the time.[150] The system would reduce the headway time between trains, so that more trains could run during rush hours, reducing passenger wait times. Trainguard MT CBTC would equip the tracks and 130 of the 340 PA5 cars being constructed by Kawasaki Railcar. The goal was to increase passenger capacity from the current 240,000 passengers to 290,000 passengers per day. The entire system was originally expected to become operational in 2017.[149][151] The entire initial order of 340 PA5 cars was completed in 2011.[152] An additional 60 PA5 cars were purchased in two subsequent optional orders.[153] In conjunction with the CBTC upgrade, the Port Authority spent $659 million to upgrade thirteen platforms on the Newark–World Trade Center line so that they could accommodate 10-car trains; prior to the upgrade, the line could only run eight-car-long trains.[154]

The Federal Railroad Administration also mandated that all railroads in the United States have positive train control, another railroad safety system, installed on their trackage by December 31, 2018. The installation of this system on the PATH was done concurrently with the installation of the CBTC signaling system, and by 2017, the PATH was ahead of schedule on its installation of positive train control.[155] The Newark–World Trade Center line west of Journal Square was converted to positive train control operation in April 2018, followed by the segments of track east and west of Journal Square in May 2018. This led to delays across the entire system when conductors had to slow down and manually adjust their trains to switch between the two signaling systems. Positive train control would be tested on the Uptown Hudson Tubes from July to October 2018, and the entire system would be converted by December.[150]

Newark Airport extension proposals

In the mid-2000s, a Newark Airport extension was again considered as the Port Authority allocated $31 million to conduct a feasibility study of extending PATH two miles (3.2 km) from Newark Penn Station.[156] In September 2012, it was announced that work would commence on the study.[157] The study estimated in 2004 the cost of the extension at $500 million.[158] On September 11, 2013, Crain's reported that New Jersey Governor Chris Christie would publicly support the PATH extension; its estimated cost grew to $1 billion.[159] The governor asked that the airport's largest operator, United Airlines, consider flying to Atlantic City International Airport as an enticement to further the project.[160]

On February 4, 2014, the Port Authority proposed a 10-year capital plan that included the PATH extension to Newark Liberty International Airport Station. The Board of Commissioners approved the Capital Plan, including the airport extension, on February 19, 2014.[161][162][163] Plans include a planned $1.5 billion PATH extension to Newark Liberty International Airport. The alignment will follow the existing Northeast Corridor approximately one mile further south to the Newark Airport station, where a connection to AirTrain Newark is available.[164] At the time, construction was expected to begin in 2018 and last five years.[165] However, in late 2014, there were calls for reconsideration of Port Authority funding priorities. The PATH extension followed the route of existing Manhattan-to-Newark Airport train service (on NJ Transit's Northeast Corridor Line and North Jersey Coast Line as well as Amtrak's Keystone Service and Northeast Regional). On the other hand, there was no funding for either the Gateway Tunnel, a pair of commuter train tunnels that would supplement the North River Tunnels under the Hudson River, or the replacement of the aging and overcrowded Port Authority Bus Terminal.[166] In December 2014, the PANYNJ awarded a three-year, $6 million contract to HNTB to perform cost analysis on the Newark Airport extension.[167]

On January 11, 2017, the PANYNJ released its 10-year capital plan that included $1.7 billion for the extension. Under the updated plan, construction was projected to start in 2020, with service in 2026.[168][169] Two public meetings on the project were held in early December 2017.[170] According to a presentation shown at these meetings, the new PATH station would include a park-and-ride lot as well as a new entrance to the station from the nearby Dayton neighborhood.[171]

Route operation

Port Authority Trans-Hudson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Weekdays | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Weekends, late nights, and holidays[172] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

PATH operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week. During weekday hours, PATH operates four train services, using three terminals in New Jersey and two in Manhattan.[173] These services are direct descendants of the four original services operated by the H&M.[22] During late nights, weekends and holidays, PATH operates two services from two terminals in New Jersey and two in Manhattan.[173]

Each line is represented by a unique color, which also corresponds to the color of the lights on the front of the trains. The Journal Square–33rd Street (via Hoboken) service is the only line represented by two colors (orange and blue), since it is a late-night/weekend/holiday combination of the Journal Square–33rd Street and Hoboken–33rd Street services. During peak hours, trains operate every four to eight minutes on each service. Every PATH station except Newark and Harrison is served by a train every two to three minutes, for a peak-hour service of 20 to 30 trains per hour.[173]

PATH management has two principal passenger outreach initiatives: the "PATHways" newsletter, distributed for free at terminals, as well as the Patron Advisory Committee.[174][175]

In 2017, PATH saw 82,812,915 total trips. On average, the system was used by 283,719 passengers per weekday; 116,383 per Saturday; 89,647 per Sunday; and 123,975 per holiday. The busiest station was World Trade Center, while the least busy station was Christopher Street.[1]

Services

The PATH system has 13.8 miles (22.2 km) of route mileage, counting route overlaps only once.[176] During the daytime on weekdays, four services operate:[173]

- Newark–World Trade Center, also known as NWK-WTC

- Hoboken–World Trade Center, or HOB-WTC

- Journal Square–33rd Street, or JSQ-33

- Hoboken–33rd Street, or HOB-33

Between 11:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m. Monday to Friday, and all-day Saturday, Sunday, and holidays, PATH operates two train services:[173]

- Newark–World Trade Center

- Journal Square–33rd Street (via Hoboken), or JSQ-33 (via HOB)

Prior to 2006, Hoboken–World Trade Center and Journal Square–33rd Street services were offered on Saturday, Sunday, and holidays between 9:00 a.m. and 7:30 p.m. On April 9, 2006, these services were indefinitely discontinued at those times, being replaced with the Journal Square–33rd Street (via Hoboken) service.[177] Passengers traveling from Hoboken to the World Trade Center were told to take the Journal Square–33rd Street service to Grove Street and transfer to the Newark–World Trade Center train.[173]

PATH does not normally operate directly from Newark to Midtown Manhattan; passengers traveling between those points are normally told to transfer to the Journal Square-33rd Street train at either Journal Square or Grove Street. However, after both 9/11 and Hurricane Sandy, special Newark–33rd Street services were operated to compensate for the loss of other lines and stations.[178][137] An intrastate Journal Square–Hoboken service was also operated after the 9/11 attacks.[123] The Journal Square–Hoboken and Newark–33rd Street services instituted after 9/11 were canceled by 2003.[178] From July to October 2018, because of positive train control installation on the Uptown Hudson Tubes, the Journal Square–33rd Street (via Hoboken) service was suspended on most weekends.[179] In the meantime, it was replaced by the Journal Square–World Trade Center (via Hoboken) and the restored Journal Square–Hoboken services, since all stations between Christopher and 33rd Streets were closed during the weekends.[172]

The lengths of trains on all lines except the Newark–World Trade Center line are limited to seven cars. This is because the platforms at Hoboken, Christopher Street, 9th Street, and 33rd Street can only accommodate seven cars and cannot be extended.[180] The Newark–World Trade Center line can accommodate trains composed of up to eight cars. In 2009, the Port Authority started upgrading platforms along that line so that it could accommodate 10-car trains.[154]

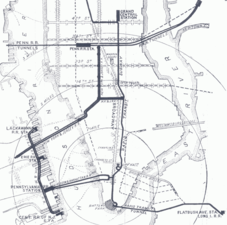

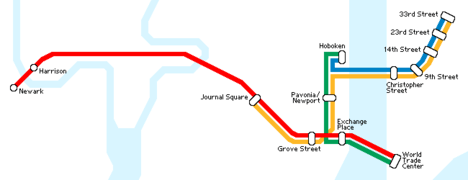

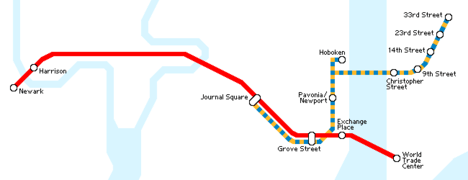

Map of PATH system (regular service)

Map of PATH system (regular service) Map of PATH system (late-night hours and on weekends/holidays)

Map of PATH system (late-night hours and on weekends/holidays) To-scale map of the PATH system

To-scale map of the PATH system

Station listing

There are currently 13 active PATH stations:[173]

| State | City | Station | Services | Opened | Connections[173] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NY | New York | 33rd Street | HOB–33 JSQ–33 |

November 10, 1910[29] | NJ Transit, Long Island Rail Road, Amtrak NYC Subway: B, D, F, M, N, Q, R, and W trains NYCT Bus[173] |

|

| 28th Street | Closed | November 10, 1910[29] | Closed September 24, 1939 when the 33rd Street station was extended southward.[181] | |||

| 23rd Street | HOB–33 JSQ–33 |

June 15, 1908[24] | NYCT Bus[173] | |||

| 19th Street | Closed | February 25, 1908[21] | Closed in 1954 when the southbound platform lost its only exit,[60] and to accelerate service[182] | |||

| 14th Street | HOB–33 JSQ–33 |

February 25, 1908[21] | NYC Subway: 1, 2, 3, F, L, and M trains NYCT Bus[173] |

|||

| 9th Street | HOB–33 JSQ–33 |

February 25, 1908[21] | NYC Subway: A, B, C, D, E, F, and M trains NYCT Bus[173] |

|||

| Christopher Street | HOB–33 JSQ–33 |

February 25, 1908[21] | NYCT Bus[173] | |||

| Hudson Terminal | Closed | July 19, 1909[25] | Closed in 1971 when service opened to World Trade Center.[183] | |||

| World Trade Center | NWK–WTC HOB–WTC |

July 6, 1971[78] | NYC Subway: 2, 3, 4, 5, A, C, E, J, N, R, W, Z, 1, and E trains NYCT Bus, MTA Bus[173] |

Closed from September 11, 2001 to November 23, 2003[184] | ||

| NJ | Hoboken | Hoboken | HOB–WTC HOB–33 |

February 25, 1908[21] | NJ Transit, Metro-North Hudson-Bergen Light Rail NJT Bus NY Waterway[173] |

|

| Jersey City | Newport | HOB–WTC JSQ–33 |

August 2, 1909[26] | Hudson-Bergen Light Rail NJT Bus, Academy Bus[173] |

Originally a station for the Erie Railroad. Formerly known as Pavonia/Newport until 2011 | |

| Exchange Place | NWK–WTC HOB–WTC |

July 19, 1909[25] | Hudson-Bergen Light Rail NJT Bus, A&C Bus[173] |

|||

| Grove Street | NWK–WTC JSQ–33 |

September 6, 1910[27] | NJT Bus, R&T Bus, A&C Bus[173] | Originally Grove-Henderson Streets | ||

| Journal Square | NWK–WTC JSQ–33 |

April 14, 1912[32]:2 | NJT Bus, R&T Bus, A&C Bus[173] | Originally Summit Avenue[32]:2 | ||

| Harrison | Harrison | NWK–WTC | June 20, 1937[59] | NJT Bus[173] | Originally one and a half blocks north (opened March 6, 1913[32]:3) | |

| Manhattan Transfer | Closed | October 1, 1911[30] | Closed in 1937 when the H&M was realigned to Newark Penn Station | |||

| Newark | Newark | NWK–WTC | June 20, 1937[59] | Amtrak, NJ Transit, Newark Light Rail NJT Bus, ONE Bus[173] |

Replacement for Park Place and Manhattan Transfer stations | |

| Park Place | Closed | November 26, 1911[31] | Closed in 1937 when the H&M was realigned to Newark Penn Station |

All terminals (33rd Street, Hoboken, World Trade Center, Journal Square and Newark) are compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, as are Exchange Place, Grove Street, and Pavonia/Newport. Harrison is currently undergoing reconstruction and will also become accessible, scheduled for completion in 2018.[185] When this project is completed, only four stations will not be accessible to wheelchair users, all of which will be in New York City.[186]

Fares

The Port Authority charges a single flat fee to ride the PATH system, regardless of distance traveled. As of October 1, 2014, a single PATH ride is $2.75; two-trip tickets are $5.50; 10-trip, $21; 20-trip, $42; 40-trip, $84 ($2.10 per trip); a seven-day unlimited, $29; and a 30-day unlimited, $89.[187][188] Single ride tickets are valid for two hours from time of purchase.[189]

| Ride Type | Price[188] | Effective Price Per Ride |

|---|---|---|

| Single Ride SmartLink/MetroCard | $2.75 | $2.75 |

| Two-Trip MetroCard | $5.50 | $2.75 |

| 10-Trip SmartLink | $21 | $2.10 |

| 20-Trip SmartLink | $42 | $2.10 |

| 40-Trip SmartLink | $84 | $2.10 |

| 1-Day Unlimited SmartLink | $8.25 | Varies by use |

| 7-Day Unlimited SmartLink | $29 | Varies by use |

| 30-Day Unlimited SmartLink | $89 | Varies by use |

| Senior SmartLink | $1 | $1 |

While some PATH stations are adjacent to or connected to New York City Subway, Newark Light Rail, Hudson-Bergen Light Rail, and New Jersey Transit stations, there are no free transfers between these different, independently run transit systems.[190]

History

Tier-based fares

The H&M formerly used a tier-based fare system where a different fare was paid based on where the passenger was traveling. For instance, prior to September 1961, an interstate fare to or from all stations except Newark Penn Station cost 25 cents, while an intrastate fare cost 15 cents. That month, the interstate fare was increased to 30 cents, and the intrastate fare to 20 cents. A fare to or from Newark Penn, regardless of the origin or destination point, was 40 cents because the station's operations were shared with the Pennsylvania Railroad at the time.[191] Under Port Authority operation, the PATH fare to and from Newark was lowered in 1966, standardizing the interstate fare to 30 cents.[192] The intrastate fare of 15 cents was doubled in 1970, effectively standardizing the fare for all trips to a flat rate of 30 cents.[193]

Tokens

PATH fares were paid with brass tokens starting in 1965. The Port Authority ordered 1 million tokens in 1962 and bought a half-million more in 1967. The Port Authority discontinued the sale of tokens in 1971 as a cost-cutting measure, since it cost $900,000 a year to maintain the token fare system. The agency replaced 175 turnstiles in the PATH's 13 stations with new turnstiles that accepted the 30-cent fare in exact change.[194]

QuickCards

A PATH fare was formerly payable with a paper ticket called the QuickCard. QuickCards, introduced in June 1990,[195] were only valid on the PATH system. They were magnetic stripe cards wherein the fare information is stored on a magnetic stripe on the front of the card.[196][197]

The QuickCard was phased out in 2008 with the introduction of the SmartLink.[198] QuickCard sales ceased at most PATH stations in early 2008; at NJ Transit ticket machines in NJ Transit stations since November 30, 2008; and at ticket machines in major PATH transfer stations since December 31, 2008.[199][200] By late 2008, PATH had completed the deactivation of all turnstiles that accepted cash (in addition to the QuickCard, MetroCard and SmartLink card). These turnstiles continued to accept the various cards as fare payment.[200]

After the QuickCard was discontinued, it was replaced by SmartLink Gray, a non-refillable, disposable version of the SmartLink card. This card was sold at selected newsstand vendors and was available in 10, 20 and 40 trip increments. Unlike regular SmartLink cards, SmartLink Gray cards had expiration dates. SmartLink Gray was itself discontinued in January 2016.[201]

Current payment methods

SmartLink

The PATH's official method of fare payment is a smart card known as SmartLink. The SmartLink was developed at a cost of $73 million, and initially was intended as a regional smart card that could be deployed on transit systems throughout the New York metropolitan area.[196] The rollout of the SmartLink started in July 2007 when it was first made available at the World Trade Center.[202] The SmartLink can be connected to an online web account system allowing a cardholder to register the card and monitor its usage. The SmartLink allows for an automatic replenishment system linked to a credit card account, wherein the card balance is automatically refilled upon reaching a threshold of 5 trips remaining (for multiple-trip cards) or 5 days remaining (for unlimited-ride cards).[203]

MetroCard

PATH fare payment may also be made using single-ride, two-trip, and pay-per-ride MetroCards, the standard farecard operated by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA).[204] The MetroCard is a magnetic stripe card, like the now defunct QuickCard. PATH riders paying their fare using MetroCard insert the card into a slot at the front of the turnstile, which reads the card and presents the MetroCard to the rider at a slot on the top of the same turnstile.[205] Other types of MetroCards, including unlimited-ride MetroCards, are not accepted on the PATH.[206]

Plans for using the MetroCard on the PATH date to 1996, when the Port Authority and MTA considered a unified fare system for the first time. At the time, the MetroCard was still being rolled out on the MTA system, and more than 80% of PATH riders transferred to other modes of transportation at some point in their trip.[197] In November 2003, the Port Authority announced that the MetroCard would be allowed for use on the PATH starting the following year.[125] The Port Authority started implementing the MetroCard on the PATH in 2005, installing new fare collection turnstiles at all PATH stations. These turnstiles allowed passengers to pay their fare with a PATH QuickCard or an MTA Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard.[207] MetroCard vending machines are located at all PATH stations. The machines sell Pay-Per-Ride MetroCards; allow riders to refill SmartLink cards; and sell Single Ride PATH tickets for use only on the PATH system. There are two types of MetroCard vending machines: large machines, which sell both MetroCards and SmartLinks and accept cash, credit cards, and transit benefits cards; and small machines, which do not accept cash or sell PATH single-ride tickets but otherwise perform the same functions as the large vending machines.[188]

In 2010, PATH introduced a two-trip card costing $4.00 using the standard MetroCard form. All PATH stations, except for the uptown platforms at 14th and 23rd Streets, contain "blue vending machines" which sell this card. The front of the card is the standard MetroCard (gold and blue) but on the reverse it has the text "PATH 2-Trip Card", "Valid for two (2) PATH trips only" and "No refills on this card". The user had to dispose of the card after the trips are used up because the turnstiles do not keep (or capture) the card as was done with the discontinued QuickCard.[188]

Rolling stock

Current roster

As of 2011, there is only one model, the PA5.[152] The cars are 51 feet (16 m) long by 9.2 feet (2.8 m) wide, a smaller loading gauge compared to similar vehicles in the US; this limitation is due to the restricted structure gauge through the tunnels under the Hudson River. They can achieve a maximum speed of 55 mph (89 km/h) in regular service. Each car seats 35 passengers, on longitudinal "bucket" seating, and can fit a larger number of standees in each car. PA5 cars have stainless steel bodies and three doors on each side. LCD displays above the windows (between the doors) display the destination of that particular train. The PA5 cars are coupled and linked into consists of up to ten cars long, with conductors' cabs on all cars and engineers' cabs on the "A" (driving) cars.[208]

In c. 2005, the Port Authority awarded a $499 million contract to Kawasaki to design and build 340 new PATH cars under the PA5 order, which replaced the system's entire existing fleet.[2] With an average age of 42 years, the fleet was the oldest of any operating heavy rail line in the United States. The Port Authority announced that the new cars would be updated versions of MTA's R142A cars. The first of these new cars entered revenue service July 10, 2009.[209] All 340 cars were delivered by 2011.[152] The Port Authority exercised a subsequent contract for 10 additional PA5 cars, bringing the total to 350.[2]

As part of the fleet expansion program and signal system upgrade, the Port Authority has the option to order a total of 119 additional PA5 cars as the option order; 44 of these cars would be to expand the NWK–WTC line to 10-car operation while the remaining 75 cars would be used to increase service frequencies once communication-based train control (CBTC) is implemented throughout the system by the end of 2018.[210] In December 2017, the Port Authority exercised an option to buy fifty extra PA5 cars for $150 million, for an ultimate total of 400 PA5 cars.[153][211] Subsequently, in July 2018, Kawasaki was awarded a $240 million contract to refurbish the 350 existing PA5 cars between 2018 and 2024. The contract also called for Kawasaki to build and deliver 72 new PA5 cars starting in 2021, for a total of 422 cars.[212][213]

The trains are stored and maintained at the Harrison Car Maintenance Facility in New Jersey, located east of the Harrison station. Another train storage yard exists east of the Journal Square Station.[214] If the Newark Airport extension is built, a third train storage yard would be built there.[171]

| Rolling stock | Year built | Builder | Car body | Car numbers | Total built | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA5 | 2008–2012 | Kawasaki | Stainless steel | 5600–5864 (A cars) 5100–5219 (C cars) |

340 base order 119 in fleet expansion option (10 A cars exercised so far;[215] 72 A and C cars in progress.[212]) |

"A" cars have cab units, "C" cars have no cabs[216] Siemens SITRAC AC propulsion system, upgradable to CBTC signalling compatibility, 3 doors per side, prerecorded station announcements |

Former roster

Before Port Authority takeover, the H&M system used rolling stock series that were given letters from A to J. All of these cars, except for the D and H series, were known as "black cars" because they were painted black.[217][218][32]:6 There were a total of 325 cars in series A through J,[217] of which 255 were black cars.[32]:6 The first 190 cars, in classes A through C, were ordered for the initial H&M service and delivered in 1909–1911. The cars, which were built in seven modular segments, measured 48.25 feet (14.71 m) long with a loading gauge of 8.83 feet (2.69 m) and a height of 12 feet (3.7 m), with longitudinal seating and three doors on each side. They were ordered to the narrow specifications of the Hudson Tubes, and were light enough that they could be tested on the Second Avenue elevated in Manhattan, which could only support lightweight trains.[23]:2 Seventy-five cars in classes E through G were added in 1921–1923, allowing the H&M to lengthen train consists from 6–7 cars each to 8 cars each. Although classes E-G had similar exterior dimensions to classes A-C, the E-G series had higher capacity, were heavier, and had substantially different window designs compared to the A-C series.[32]:6 The last order of black cars, the 20 cars in series J, was delivered in 1928.[32]:6–7 Many of the black cars remained in service from their inception until the H&M's bankruptcy in 1954. By that time, the black cars required large amounts of maintenance.[218]

The PRR and H&M joint service comprised 40 cars in classes D and H, which were owned by the H&M, as well as 72 cars from the MP38 class, which were owned by the PRR.[217] Sixty MP38s and 36 Class D cars were delivered in 1911, when the service first operated.[7]:43[219] In 1927, an additional twelve MP38 cars were ordered under the MP38A classification, as well as four Class H cars.[217][32]:6 As a result of the different manufacturers and the long duration between the two pairs of orders, the Class D and MP38 cars' designs were noticeably different from the Class H and MP38A cars' designs.[32]:6–7 The red cars were branded with the names of both companies to signify the partnership.[220] The red cars suffered from corrosion and design defects, and were unusable by 1954.[218] All of the red and black car series were designed to be operationally compatible, which meant that a train consist could be made up of cars from any of the series.[32]

The MP52 and K-class, which replaced the D-class and the 60 MP38s ordered in 1911, comprised an order of 50 cars. The MP52 (30 cars) and K-class (20 cars) were purchased by the PRR and H&M respectively and delivered in 1958 in order to save money on the maintenance of the existing cars.[217][221]

After the Port Authority took over operation of the H&M Railroad in 1962, it started ordering new rolling stock to replace the old H&M cars.[74] St. Louis Car built 162 PA1 cars in 1964–1965.[7]:101[73][74] St. Louis also built the PA2, a supplementary order of 44 cars, in 1966–1967.[7]:101[75] Hawker Siddeley built 46 PA3 cars in 1972.[7]:101[75] The 95 PA4s were built by Kawasaki Heavy Industries in 1986–1987, replacing the K-class and MP52 series.[7]:101[222]

PA1, PA2, and PA3 cars had painted aluminum bodies, and two doors on each side. Back-lit panels above the doors displayed the destination of that particular train: HOB for Hoboken, JSQ for Journal Square, NWK for Newark, 33 for 33rd Street, and WTC for World Trade Center.[7]:81 In the mid-1980s, Kawasaki overhauled 248 of the 252 PA1-PA3 cars at their factory in Yonkers, New York, and repainted these cars white to match the PA4 cars being delivered at the time.[7]:81[222][223] PA4 cars had stainless steel bodies, and three doors on each side. Back-lit displays above the windows (between the doors) displayed the destination of that particular train.[7]:81 All four series were designed to be operationally compatible.[224] Although all four orders contained "A" cars with cabs at one end, the PA1 and PA2 orders also contained some "C" cars. The ends of a train had to comprise an "A" car, but an even number of "A" cars and a variable number of "C" cars could be placed in the middle of the consist. This meant that, for instance, consists of cars coupled in A-A-A-A, A-C-C-A, or A-A-A-C-C-A sequence were operable, but not consists of cars coupled in A-A-A or A-A-C-A sequence. Trains could comprise between 3 and 8 cars.[180] All PA1-PA4 equipment were retired from passenger service in 2009–2011.[152]

| Rolling stock | Year built | Year retired | Builder | Car body | Car numbers | Total built | Notes[23][219][32][217][7]:101 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1908 | 1955 | Pressed Steel and American Car & Foundry | painted steel (black) | 200–249 | 50 | Pressed Steel built 10 cars numbered 200–209. American Car & Foundry built the remaining 40 cars numbered 210–249. |

| B | 1909 | 1964–1967 | Pressed Steel | painted steel (black) | 250–339 | 90 |

Car 318 was wrecked at 33rd Street on January 16, 1931.[225] |

| C | 1910 | 1964–1967 | American Car & Foundry | painted steel (black) | 340–389 | 50 | |

| D | 1911 | 1958 | Pressed Steel | painted steel (red) | 701–736 | 36 |

|

| MP38 | 1911 | 1964–1967 | Pressed Steel | painted steel (red) | 1901–1960 | 60 | "Red cars" used in the H&M/PRR joint service and owned by the PRR. |

| E | 1921 | 1966–1967 | American Car & Foundry | painted steel (black) | 401–425 | 25 | |

| F | 1922 | 1966–1967 | American Car & Foundry | painted steel (black) | 426–450 | 25 | |

| G | 1923 | 1966–1967 | American Car & Foundry | painted steel (black) | 451–475 | 25 | |

| H | 1927 | 1966–1967 | American Car & Foundry | painted steel (red) | 801–804 | 4 | "Red cars" used in the H&M/PRR joint service and owned by the H&M. |

| MP38A | 1927 | 1966–1967 | American Car & Foundry | painted steel (red) | 1961–1972 | 12 | "Red cars" used in the H&M/PRR joint service and owned by the PRR. |

| J | 1928 | 1966–1967 | American Car & Foundry | painted steel (black) | 501–520 | 20 | 503 at Shore Line Trolley Museum. 510 and 513 at Trolley Museum of New York. |

| MP52 | 1958 | 1987 | St. Louis Car Company | aluminum | 1200–1229 | 30 |

|

| K | 1958 | 1987 | St. Louis Car Company | aluminum | 1230–1249 | 20 |

|

| PA1 | 1964–1965 | 2009–2011 | St. Louis Car Company | painted aluminum | 100–151 ("C" cars) 600–709 ("A" cars) |

162 (110 cab units, 52 trailers) |

|

| PA2 | 1966–1967 | 2009–2011 | St. Louis Car Company | painted aluminum | 152–181 ("C" cars) 710–723 ("A" cars) |

44 (14 cab units, 30 trailers) |

|

| PA3 | 1972 | 2009–2011 | Hawker-Siddeley | painted aluminum | 724–769 | 46 |

|

| PA4 | 1986–1987 | 2009–2011 | Kawasaki | Stainless steel | 800–894 | 95 |

|

A PATH train consisting of cars 745, 143, 160, 845, 750, 139, and 612 was left under the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. The collapse of the south tower largely destroyed the train; cars 745 and 143 were not positioned directly beneath the tower and were the only cars to survive the collapse relatively intact. These two cars were cleaned and placed in storage following the collapse while the remains of the rest of the train had been stripped of usable parts and scrapped. The cars were intended to be displayed in the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.[226] However, the cars were deemed too large to be displayed in the museum; as a result, car 745 was instead donated to the Shore Line Trolley Museum,[227] while car 143 was donated to the Trolley Museum of New York.[228]

FRA railroad status

.jpg)

While the PATH resembles a typical intraurban heavy rail rapid transit system, it is actually under the jurisdiction of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), which oversees railroads that are part of the national railroad infrastructure.[229] PATH used to share trackage with the Pennsylvania Railroad between Hudson interlocking near Harrison and Journal Square. The line also connected to Amtrak's Northeast Corridor near Harrison station and also near Hudson tower. All of these connections have since been severed, as the track layout at Hudson interlocking has been modified considerably. Despite PATH now being an isolated rail system, FRA regulations still apply to the PATH because of the PATH tracks' proximity to Amtrak trackage.[230] The PATH also uses one bridge operated by Amtrak: the Dock Bridge near Newark Penn Station.[231]

While PATH operates under several grandfather waivers, it is required to do things not typically seen on American transit systems. Some of these include the proper fitting of grab irons to all PATH rolling stock, the use of federally certified locomotive engineers, installation of positive train control (PTC), and compliance with the federal railroad hours of service regulations. This raises the PATH's per-hour operating costs relative to other railroad systems in the New York City and Philadelphia areas.[214]

Media and popular culture

Media restrictions

The PATH regulations as of December 20, 2015 state that all photography, film making, video taping, or creations of drawings or other visual depictions within the PATH system is prohibited without a permit by PATH and supervision by a PATH representative.[232]:17 According to the rules, photographers, filmmakers, and other individuals must obtain permits through an application process.[232]:18 Although it has been suggested that the restriction was put in place due to terrorism concerns, the restriction predates 9/11.[233]

_(6390625079).jpg)

It is thought that this ban excludes members of the general public who want to take pictures, and the photography and filmography ban only applies to commercial or professional purposes. The general public is allowed to take pictures of PATH stations and all other Port Authority facilities except in secure and off-limits areas.[233] There have been decisions from the United States Supreme Court stating that casual photography is covered by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. However, the case law is mixed. Under the law PATH employees may not force a casual photographer to destroy or surrender their film or images, but confiscations and arrests have occurred. Litigation following such confiscations or arrests have generally, but not always, resulted in the dropping of charges or the awarding of damages.[234]

Tunnel decoration

On trains bound for Newark or Hoboken from World Trade Center, a short, zoetrope-like advertisement was formerly visible in the tunnel before entering Exchange Place. There was formerly another similar advertisement, visible from 33rd Street-bound trains between 14th and 23rd Streets near the abandoned 19th Street station.[235]

Every year, around Thanksgiving, PATH employees light a decorated Christmas tree at the switching station adjacent to the tunnel used by trains entering the Pavonia/Newport station. This tradition has continued since the 1950s when a signal operator, Joe Wojtowicz, started hanging a string of Christmas lights in the tunnel. While PATH officials were initially concerned about putting up decorations in the tunnel, they later acquiesced and the tradition continued. After the September 11 attacks, a back-lit U.S. flag was put up beside the tree as a tribute to the victims of the attacks.[236]

In popular culture

PATH trains and stations have occasionally been the setting for music videos, commercials, movies, and TV programs. For instance, the video for the White Stripes's song "The Hardest Button to Button" was taped at the 33rd Street station.[237] Additionally, the premiere for season 19 of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit was filmed in the World Trade Center station.[238] The PATH may also be used as a stand-in for the New York City Subway.[239]

Major incidents

Train collisions

On August 31, 1922, two H&M trains collided at Manhattan Transfer because of heavy fog, injuring 50 people, eight of them seriously.[240] Another collision near the same location less than a year later, on July 22, 1923, killed one person and injured 15 others.[241]

A seven-car H&M train derailed a switch and collided with a wall at 33rd Street on January 16, 1931, injuring 19 passengers.[242] In a similar accident on August 22, 1937, a 5-car H&M train crashed into a wall at Hudson Terminal, injuring 33 passengers.[243]

On November 26, 1938, twenty-two passengers were injured when an H&M train sideswiped a PRR engine in Kearny, east of the former Manhattan Transfer station.[244] A similar accident happened on July 23, 1963, when a PATH train collided with a PRR engine east of Harrison, killing two passengers and injuring 28 more.[245]

On April 26, 1942, a six-car H&M train derailed at Exchange Place. Five people were killed and 222 more were injured. A subsequent investigation found that the motorman had been intoxicated at the time.[246] On December 17, 1945, a seven-car H&M train collided with a steel barrier on the Dock Bridge west of Harrison, killing the motorman and injuring 67 passengers.[247]

A PATH train rear-ended another train at Journal Square on December 13, 1958, injuring 30 passengers, none seriously.[248] Nine years later, on January 11, 1968, another rear-end accident at the same location injured 100 of the approximately 200 combined passengers on the two trains, 25 of them seriously. No one was killed.[249]

On October 21, 2009, a PATH train crashed into a barricade at the end of the platform at 33rd Street. Approximately 13 of the 450 people riding the seven-car train suffered minor injuries, and seven people including two crew members and five passengers were taken to nearby hospitals. An investigation by the Port Authority determined that the accident was caused by human error.[250] In a similar crash on May 8, 2011, a PATH train crashed into a barricade at Hoboken Terminal, injuring 34 people.[250][251] This crash was attributed to the train's excessive speed.[252]

Other incidents

A train near Exchange Place caught fire on June 3, 1982, injuring 28 people.[253]

Part of the ceiling at Journal Square fell onto the platform on August 9, 1983, killing 2 and injuring 8.[254][255]

On January 7, 2013, an escalator at Exchange Place suddenly reversed itself, resulting in five injuries.[256]

See also

- Transportation in New York City

- PATCO Speedline, a similar rapid transit/commuter line connecting South Jersey to Philadelphia

- List of metro systems

References

- 1 2 3 "2017 PATH Monthly Ridership Report" (PDF). pathnynj.gov. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Project Detail". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. June 25, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2018.