Autocephaly

Autocephaly (/ˌɔːtəˈsɛfəli/; from Greek: αὐτοκεφαλία, meaning "property of being self-headed") is the status of a hierarchical Christian Church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Independent Catholic churches.

Overview

In the first centuries of history of the Christian church, the autocephalous status of a local church was promulgated by canons of the ecumenical councils. Thus, there developed the pentarchy, i.e. a model of Church organization where the universal Church was governed by the primates (patriarchs) of the five major episcopal sees of the Roman Empire: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.[1] Additionally, the Church of Cyprus, previously within the Church of Antioch, was granted autocephaly by Canon VIII of the Council of Ephesus[2] and has since been governed by the Archbishop of Cyprus, who is not subject to any higher ecclesiastical authority.

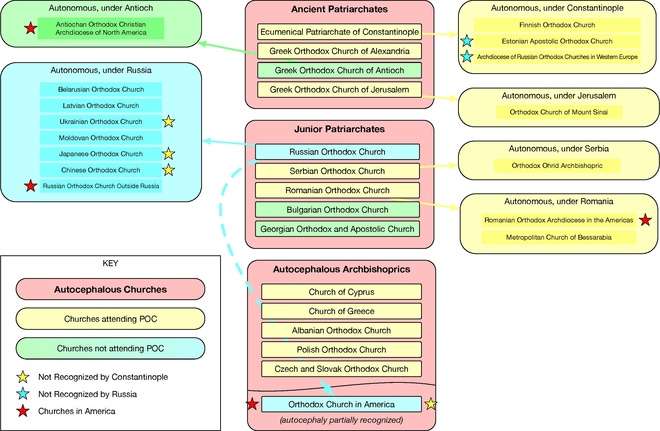

The right to grant autocephaly is nowadays a contested issue, the main opponents in the dispute being the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which claims this right as its prerogative,[3] and the Russian Orthodox Church (the Moscow Patriarchate), which insists that an already established autocephaly has the right to grant independence to a part thereof.[4][5] Thus, the Orthodox Church in America was granted autocephaly by the Moscow Patriarchate in 1970, but this new status was not recognized by most patriarchates.[6] In the modern era the issue of autocephaly has been closely linked to the issue of self-determination and political independence of a nation, or a country; self-proclamation of autocephaly was normally followed by a long period of non-recognition and schism with the mother church.

Modern era historical precedents

Following the establishment of an independent Greece in 1832, the Greek government in 1833 unilaterally proclaimed the Orthodox Church in the kingdom (until then within the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate) to be autocephalous. It was not until June 1850 that the Mother Church, under the Patriarch Anthimus IV, recognised this status.[7]

In May 1872, the Bulgarian Exarchate, set up by the Ottoman government two years prior, broke away from the Ecumenical Patriarchate, following the start of the struggle for national self-determination. The Bulgarian Church was recognised as an autocephalous patriarchate in 1945, after decades of schism.

Following the Congress of Berlin (1878), which established Serbia′s political independence, full ecclesiastical independence for the Metropolitanate of Belgrade was negotiated and recognised by the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 1879. Additionally, in the course of the 1848 revolution, following the proclamation of the Serbian Vojvodina (Serbian Duchy) within the Austrian Empire in May 1848, the autocephalous Patriarchate of Karlovci was instituted by the Austrian government to be abolished in 1920, shortly after the dissolution of the Austria-Hungary in 1918 and Vojvodina being incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The Patriarchate of Karlovci was merged into the newly united Serbian Orthodox Church under Patriarch Dimitrije residing in Belgrade, the capital of the new country that comprised all the Serb-populated lands. The united Serbian Church also incorporated the hitherto autonomous Church in Montenegro whose independence was formally abolished by Regent Alexander′s decree in June 1920.

The autocephalous status of the Romanian Church, legally mandated by the local authorities in 1865, was recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 1885, following the international recognition of the independence of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (later Kingdom of Romania) in 1878.[8]

In late March 1917, following the abdication of the Russian tsar Nicholas II earlier that month and the establishment of the Special Transcaucasian Committee, the bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church in Georgia, then within the Russian Empire, unilaterally proclaimed independence of the Georgian Orthodox Church, which was not recognised by the Moscow Patriarchate until 1943 and by the Ecumenical Patriarchate until 1990.[9][10][11]

The independent Kiev Patriarchate was proclaimed in 1992, shortly after the proclamation of independence of Ukraine and the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, and remains condemned as schismatic by the Moscow Patriarchate, which claims jurisdiction over Ukraine, and unrecognised by the other Orthodox Churches. In 2018, the problem of autocephaly in Ukraine became a fiercely contested issue and a part of the overall geopolitical confrontation between Russia and Ukraine as well as between the Moscow Patriarchate and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[12][13][14]

Similar situation persists in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, where the Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric remains canonically unrecognised since it split off from the Serbian Church and proclaimed autocephaly in 1967. The Serbian Church has the Orthodox Ohrid Archbishopric in the Republic of Macedonia.

Autocephaly and autonomy

One step short of autocephaly is autonomy. A church that is autonomous has its highest-ranking bishop, such as an archbishop or metropolitan, approved (or ordained) by the primate of the mother church, but is self-governing in all other respects. The modern Russian Orthodox Church (the Moscow patriarchate) also has the so called "self-governing churches", such as the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), in addition to churches that it refers to as "autonomous" such as the Japanese Orthodox Church, which until 2011 were not regarded as constituent part of the Moscow Patriarchate.[15]

Autocephalous and autonomous churches

POC: Pan-Orthodox Council

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ "Pentarchy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

The proposed government of universal Christendom by five patriarchal sees under the auspices of a single universal empire. Formulated in the legislation of the emperor Justinian I (527–65), especially in his Novella 131, the theory received formal ecclesiastical sanction at the Council in Trullo (692), which ranked the five sees as Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

- ↑ Schaff & Wace 1900, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Erickson 1991.

- ↑ Sanderson 2005, p. 144.

- ↑ Jillions, John (7 April 2016). "The Tomos of Autocephaly: Forty-Six Years Later". Orthodox Church in America. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ Hovorun 2017, pp. 82, 126; Sanderson 2005, pp. 130, 144.

- ↑ Γιώργος Καραγιάννης (1997). Εκκλησία και Κράτος 1833-1997. Εκδόσεις «Το Ποντίκι». p. 24. ISBN 9608402492.

- ↑ Keith Hitchins, Rumania 1866-1947, Clarendon Press, 1994, p. 92

- ↑ Grdzelidze 2010, p. 61, 172.

- ↑ Автокефалия на волне революции: Грузинское православие в орбите Российской церкви Nezavisimaya Gazeta, 15 March 2017.

- ↑ Other Autocephalous Churches: Ἐκκλησία τῆς Γεωργίας

- ↑ ECUMENICAL PATRIARCH TAKES MOSCOW DOWN A PEG OVER CHURCH RELATIONS WITH UKRAINE orthodoxyindialogue.com, 2 July 2018.

- ↑ Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew: “As the Mother Church, it is reasonable to desire the restoration of unity for the divided ecclesiastical body in Ukraine” (The Homily by Patriarch Bartholomew after the memorial service for the late Metropolitan of Perge, Evangelos) The official website of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, 2 July 2018.

- ↑ Raphael Satter (27 August 2018). "Russian Cyberspies Spent Years Targeting Orthodox Clergy". Associated Press. Bloomberg.

- ↑ Определение Освященного Архиерейского Собора Русской Православной Церкви «О внесении изменений и дополнений в Устав Русской Православной Церкви» patriarchia.ru. 5 February 2011.

Bibliography

- Erickson, John H. (1991). The Challenge of Our Past: Studies in Orthodox Canon Law and Church History. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-086-0.

- ——— (1999). Orthodox Christians in America: A Short History. New York: Oxford University Press (published 2010). ISBN 978-0-19-995132-1.

- Grdzelidze, Tamara (2010). "The Orthodox Church of Georgia: Challenges under Democracy and Freedom (1990–2009)". International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church. 10 (2–3): 160–175. doi:10.1080/1474225X.2010.487719. ISSN 1747-0234.

- ——— (2012). "The Georgian Tradition". In Casiday, Augustine. The Orthodox Christian World. Abingdon, England: Routledge. pp. 58–65. ISBN 978-0-415-45516-9.

- Hovorun, Cyril (2017). Scaffolds of the Church: Towards Poststructural Ecclesiology. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5326-0753-0.

- Sanderson, Charles Wegener (2005). Autocephaly as a Function of Institutional Stability and Organizational Change in the Eastern Orthodox Church (PhD diss.). College Park, Maryland: University of Maryland, College Park. hdl:1903/2340.

- Schaff, Philip; Wace, Henry, eds. (1900). A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church. Series 2. Volume 14: The Seven Ecumenical Councils. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers (published 1995). ISBN 978-1-56563-130-4.

|access-date=requires|url=(help)

Further reading

- "Autocephaly". OrthodoxWiki. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- Papakonstantinou, Christoporos (1999). "Autocephaly". In Fahlbusch, Erwin; Lochman, Jan Milič; Mbiti, John; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Vischer, Lukas; Bromiley, Geoffrey W.; Barrett, David B. Encyclopedia of Christianity. 1. Translated by Bromiley, Geoffrey W. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8028-2413-4.

- Shahan, Thomas J. (1907). "Autocephali". In Herbermann, Charles G.; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé B.; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. Catholic Encyclopedia. 2. New York: Encyclopedia Press (published 1913). pp. 142–143.