History of Oriental Orthodoxy

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

Subdivisions

|

|

History and theology

|

|

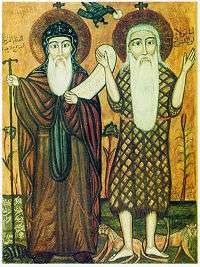

Major figures

|

|

|

Oriental Orthodoxy is the communion of Eastern Christian Churches that recognize only three ecumenical councils — the First Council of Nicaea, the First Council of Constantinople and the Council of Ephesus. They reject the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon. Hence, these Churches are also called Old Oriental Churches or Non-Chalcedonian Churches.

Foundation

The history of all Oriental Orthodox Churches goes back to the very beginnings of Christianity. [1] They were founded by the apostles or by their earliest disciples and their theology did not undergo any significant change in the course of their history.

Missionary role

The Oriental Orthodox Churches had a great missionary role during the early stages of Christianity and played a great role in the history of Egypt.[2]

Chalcedonian Schism

According to the canons of the Oriental Orthodox Churches, the four bishops of Rome, Alexandria, Ephesus (later transferred to Constantinople) and Antioch were all given status as Patriarchs; in other words, the ancient apostolic centres of Christianity, by the First Council of Nicaea (predating the schism) — each of the four patriarchs was responsible for those bishops and churches within his own area of the Universal Church, (with the exception of the Patriarch of Jerusalem, who was independent of the rest). Thus, the Bishop of Rome has always been held by the others to be fully sovereign within his own area, as well as "First-Among-Equals", due to the traditional belief that the Apostles Saint Peter and Saint Paul were martyred in Rome.

The schism between Oriental Orthodoxy and the rest of the Church occurred in the 5th century. The separation resulted in part from the refusal of Pope Dioscorus, the Patriarch of Alexandria, to accept the Christological dogmas promulgated by the Council of Chalcedon, which held that Jesus has two natures: one divine and one human. This was not because Chalcedon stated that Christ has two natures, but because the council's declaration did not confess the two natures as inseparable and united. Pope Dioscorus would accept only "of or from two natures" but not "in two natures." To the hierarchs who would lead the Oriental Orthodox, this was tantamount to accepting Nestorianism, which expressed itself in a terminology incompatible with their understanding of Christology. Founded in the Alexandrine School of Theology it advocated a formula stressing the unity of the Incarnation over all other considerations.

The Oriental Orthodox churches were therefore often called Monophysite, although they reject this label, as it is associated with Eutychian Monophysitism; they prefer the term "non-Chalcedonian" or "Miaphysite" churches. Oriental Orthodox Churches reject what they consider to be the heretical Monophysite teachings of Eutyches and of Nestorius as well as the Dyophysite definition of the Council of Chalcedon. The reason for the excommunication of the non-Chalcedonian bishops by the Bishops of Rome and Constantinople in 451, that formalized the schism, was the teaching that Jesus Christ has two natures (dyophysitism), which the Council of Chalcedon upheld as a dogma.

Christology, although important, was not the only reason for the Coptic and Syriac refusal of the Council of Chalcedon; political, ecclesiastical and imperial issues were hotly debated during that period.[3]

Failed attempts towards reconciliation

In 482, Byzantine emperor Zeno made an attempt to reconcile christological differences between the supporters and opponents of the Chalcedonian Definition, by issuing imperial decree known as Henotikon, but those efforts were mainly politically motivated and ultimately proved to be unsuccessful in reaching the true and substantial reconciliation.[4]

In the years following the Henotikon, patriarchs of Constantinople remained in formal communion with the non-Chalcedonian patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, while Rome remained out of communion with them, and in unstable communion with Constantinople (see: Acacian schism). It was not until 518 that the new Byzantine Emperor, Justin I (who accepted Chalcedon), demanded that the entire Church in the Roman Empire accept the Council's decisions. Justin ordered the replacement of all non-Chalcedonian bishops, including the patriarchs of Antioch and Alexandria.[3]

During the reign of emperor Justinian I (527-565), new attempts were made towards reconciliation. One of the most prominent Oriental Orthodox theologians of that era was Severus of Antioch. In spite of several, imperially sponsored meetings between heads of Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox communities, no final agreement was reached. The split proved to be final, and by that time parallel ecclesiastical structures were formed throughout the Middle East. Most prominent Oriental Orthodox leader in the middle of the 6th century was Jacob Baradaeus, who was seen as the leader of the community, known from that time as "Jacobite" Christians.[3]

Between Byzantine and Persian empires

During the 6th and 7th, frequent wars between the Byzantine Empire an the Sasanian Empire (Persia), fought throughout the Middle East, greatly affected all Christians in the region, including Oriental Orthodox, specially in Armenia, Byzantine Syria and Byzantine Egypt. Temporary Persian conquest of all those regions during the great Byzantine-Sassanid War of 602-628 resulted in further estrangement between Oriental Orthodox communities of the region and the Byzantine imperial government in Constantinople. Those relations did not improve after the Byzantine reconquest, in spite of the efforts of emperor Heraclius, who tried to strengthen political control of the region by achieving religious reunification of divided Christian communities. In order to reach a christological compromise between Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox, he supported monoenergism and monothelitism, but without much cusses.[3]

Arab conquest and its aftermath

Challenges of Islamization

Following the Muslim conquest of the Middle East in the 7th century, process of gradual Islamization was initiated, affecting all Christians in the region, including Oriental Orthodox. The indigenous Oriental Orthodox communities, mainly Syriac and Coptic, underwent gradual conversion from Christianity to Islam. This process was also accompanied by gradual Arabization. In spite of that, Oriental Orthodox communities in the Middle East endured, preserving their Christian faith and culture.[5]

Ottoman conquest and the Millet system

During the first half of the 16th century, entire Middle East fell under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Syria and Egypt were conquered during the Ottoman-Mamluk War (1516-1517), and Oriental Orthodox communities in the region faced new political reality that would determine their history until the beginning of the 20th century. Ottoman government introduced the Millet system that recognized a certain degree of autonomy to non-Islamic religious communities, including Oriental Orthodox Christians.

Persecution of Oriental Orthodoxy

One of the most salient features of the history of Oriental Orthodoxy has been the ceaseless persecution and massacres suffered under Byzantine, Persian, Muslim and Ottoman powers.[6] Anti-Oriental Orthodox sentiments in the Byzantine Empire were motivated by religious divisions within Christianity after the Council of Chalcedon in 451. First persecutions occurred mainly in Egypt and some other eastern provinces of the Byzantine Empire, during reigns of emperors Marcian (450-457) and Leo I (457-474).[7]

In modern times, persecutions of Oriental Orthodox Christians culminated with Ottoman systematic persecutions of Armenian Christians, that led to the Armenian Genocide during the first World War. Also, Coptic Christians in Egypt have been victims of persecution by Muslim extremists up to the modern times.

Modern days

The Oriental Orthodox communion comprises six groups: Coptic Orthodox, Syriac Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox, Eritrean Orthodox, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (India) and Armenian Apostolic churches.[8] These six churches, while being in communion with each other are completely independent hierarchically and have no equivalent of the Bishop of Rome or Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, [9] with no concepts of supremacy or precedence respectively.

By the 20th century the Chalcedonian Schism was not seen with the same relevance, and from several meetings between the authorities of Roman Catholicism and the Oriental Orthodoxy, reconciling declarations emerged in the common statement of the Oriental Patriarch (Mar Ignatius Zakka I Iwas) and the Pope (John Paul II) in 1984.

| “ | The confusions and schisms that occurred between their Churches in the later centuries, they realize today, in no way affect or touch the substance of their faith, since these arose only because of differences in terminology and culture and in the various formulae adopted by different theological schools to express the same matter. Accordingly, we find today no real basis for the sad divisions and schisms that subsequently arose between us concerning the doctrine of Incarnation. In words and life we confess the true doctrine concerning Christ our Lord, notwithstanding the differences in interpretation of such a doctrine which arose at the time of the Council of Chalcedon.[10] | ” |

Ecumenical relations

After the historical Conference of Addis Ababa in 1965, major Oriental Orthodox Churches have developed the practice of mutual theological consultations and joint approach to ecumenical relations with other Christian denominations, particularly with Eastern Orthodox Churches and the Anglican Communion. Renewed discussions between Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox theologians were mainly focused on christological questions regarding various differences between monophysitism and miaphysitism.[11][12] On the other hand, dialog between Oriental Orthodox and Anglican theologians was also focused on some additional pneumatological questions. In 2001, joint "Anglican-Oriental Orthodox International Commission" was created.[13] In following years, the Commission produced several important theological statements. Finally in 2017, Oriental Orthodox and Anglican theologians met in Dublin and signed an agreement on various theological questions regarding the teachings on the Holy Spirit. The statement of agreement has confirmed the Anglican readiness to omit the Filioque interpolation from the Creed.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ "FindArticles.com - CBSi". findarticles.com. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ "Oriental Orthodox church - Christianity". Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Meyendorff 1989.

- ↑ Meyendorff 1989, pp. 194-202.

- ↑ Betts 1978.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia Coptica: The Christian Coptic Orthodox Church Of Egypt". www.coptic.net. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ Meyendorff 1989, p. 187-194.

- ↑ WCC-COE.org Archived 2010-04-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Michael Allen - The Pluralism Project". www.pluralism.org. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ From the common declaration of Pope John Paul II and HH Mar Ignatius Zakka I Iwas, June 23, 1984

- ↑ "Orthodox Unity (Orthodox Joint Commission)". Orthodox Unity (Orthodox Joint Commission). Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ Christine Chaillot (ed.), The Dialogue between Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches, International Edition 2016.

- ↑ Office, Anglican Communion. "Anglican Communion: Oriental Orthodox". Anglican Communion Website. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ "Historic Anglican – Oriental Orthodox agreement on the Holy Spirit signed in Dublin". www.anglicannews.org. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

Bibliography

- Betts, Robert B. (1978). Christians in the Arab East: A Political Study (2nd rev. ed.). Athens: Lycabettus Press.

- Charles, Robert H. (2007) [1916]. The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu: Translated from Zotenberg's Ethiopic Text. Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing.

- Krikorian, Mesrob K. (2010). Christology of the Oriental Orthodox Churches: Christology in the Tradition of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Peter Lang.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450-680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.