Tengrism

| Part of a series on |

| Tengrism |

|---|

|

| A Central Asian religious belief and mythology. |

| Related movements |

| People |

| Deities |

| Scriptures |

| Places |

| Priests |

| Related conceptions |

| Also historically and geographically covered Siberia and parts of East Asia. |

Tengrism, also known as Tengriism, Tenggerism or Tengrianism, is a Central Asian religion characterized by shamanism, animism, totemism, poly- and monotheism[1][2][3] and ancestor worship. It was the prevailing religion of the Turks, Mongols, Hungarians, Xiongnu and Huns,[4][5] and the religion of the five ancient Turkic states: Göktürk Khaganate, Western Turkic Khaganate, Great Bulgaria, Bulgarian Empire and Eastern Tourkia (Khazaria). In Irk Bitig, Tengri is mentioned as Türük Tängrisi (God of Turks).[6]

Tengrism has been advocated in intellectual circles of the Turkic nations of Central Asia (including Tatarstan, Buryatia, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan) since the dissolution of the Soviet Union during the 1990s.[7] Still practiced, it is undergoing an organized revival in Sakha, Khakassia, Tuva and other Turkic nations in Siberia. Burkhanism, a movement similar to Tengrism, is concentrated in Altay.

Khukh tengri means "blue sky" in Mongolian, Mongolians still pray to Munkh Khukh Tengri ("Eternal Blue Sky") and Mongolia is sometimes poetically called the "Land of Eternal Blue Sky" (Munkh Khukh Tengriin Oron) by its inhabitants. In modern Turkey, Tengrism is known as the Göktanrı dini ("Sky God religion");[8] the Turkish "Gök" (sky) and "Tanrı" (God) correspond to the Mongolian khukh (blue) and Tengri (sky), respectively. According to Hungarian archaeological research, the religion of the Hungarians until the end of the 10th century (before Christianity) was Tengrism.[9]

Background

.png)

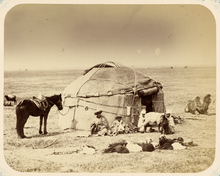

Tengrists view their existence as sustained by the eternal blue sky (Tengri), the fertile mother-earth spirit (Eje) and a ruler regarded as the holy spirit of the sky. Heaven, earth, spirits of nature and ancestors provide for every need and protect all humans. By living an upright, respectful life, a human will keep his world in balance and perfect his personal Wind Horse, or spirit. The Huns of the northern Caucasus reportedly believed in two gods: Tangri Han (or Tengri Khan), considered identical to the Persian Aspandiat and for whom horses were sacrificed, and Kuar (whose victims are struck by lightning).[5] Tengrism is practised in Sakha, Buryatia, Tuva and Mongolia in parallel with Tibetan Buddhism and Burkhanism.[11]

Kyrgyz means "we are forty" in the Kyrgyz language, and Kyrgyzstan's flag has 40 uniformly-spaced rays. Tengrist Khazars aided Heraclius by reportedly sending 40,000 soldiers during a joint Byzantine-Göktürk operation against the Persians.

Several Kyrgyz politicians are advocating Tengrism to fill a perceived ideological void. Dastan Sarygulov, secretary of state and former chair of the Kyrgyz state gold-mining company, established the Tengir Ordo (Army of Tengri): a civic group promoting the values and traditions of Tengrism.[12] Sarygulov also heads a Tengrist society in Bishkek claiming nearly 500,000 followers and an international scientific center of Tengrist studies.

Articles on Tengrism have been published in social-scientific journals in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev and former Kyrgyz president Askar Akayev have called Tengrism the national, "natural" religion of the Turkic peoples.

Symbols

.svg.png)

- Gun Ana - the sun (featured in most flags)

- Umay – Goddess of fertility and virginity

- Bai-Ulgan – Greatest deity, after Tengri

- Erkliğ – God of space

- Erlik – God of death

- Flag of Sakha Republic

- Flag of Kazakhstan

- Flag of Chuvashia

- Göktürk coins

- Tree of Life

- Öksökö

Tengri

Tengrism was brought to Eastern Europe by the early Huns and Bulgars.[13] It lost importance when the Uighuric kagans proclaimed Manichaeism the state religion in the eighth century.[14]

Tengrism also played a large role in the religion of the Gok-Turk and Mongol Empires. Gok-Turk translates as "celestial Turk". Genghis Khan and several generations of his followers were Tengrian believers until his fifth-generation descendant, Uzbeg Khan, turned to Islam in the 14th century.

The original Mongol khans, followers of Tengri, were known for their tolerance of other religions.[15] Möngke Khan, the fourth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, said: "We believe that there is only one God, by whom we live and by whom we die, and for whom we have an upright heart. But as God gives us the different fingers of the hand, so he gives to men diverse ways to approach him." ("Account of the Mongols. Diary of William Rubruck", religious debate in court documented by William of Rubruck on May 31, 1254).

Central Asia

A revival of Tengrism has played a role in Central Asian Turkic nationalism since the 1990s. It developed in Tatarstan, where the Tengrist periodical Bizneng-Yul appeared in 1997. The movement spread during the 2000s to Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan and, to a lesser extent, Buryatia and Mongolia.

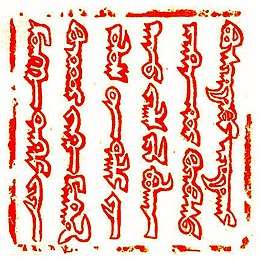

Temdeg Symbol and Tengriism

Temdeg Writing

- ᠲ᠋ᠠ᠊ᠮᠳ᠋ᠠ᠊ᠢ᠊ᠡ᠋

- (тэмдэг)

The term "shamanism" was first applied by Western anthropologists as outside observers of the ancient religion of the Turks and Mongols, as well as those of the neighbouring Tungusic and Samoyedic-speaking peoples. Upon observing more religious traditions across the world, some Western anthropologists began to also use the term in a very broad sense. The term was used to describe unrelated magico-religious practices found within the ethnic religions of other parts of Asia, Africa, Australasia and even completely unrelated parts of the Americas, as they believed these practices to be similar to one another.

Since the 1990s, Russian-language literature uses Тенгрианство ("Tengrism" or "Tengrinity") in the general sense of Mongolian shamanism. Buryat scholar Irina S. Urbanaeva developed a theory of Tengrianist esoteric traditions in Central Asia after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the revival of national sentiment in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia.[18]

Although Tengrism has few active adherents, its revival of a national religion reached a larger audience in intellectual circles. Presenting Islam as foreign to the Turkic peoples, adherents are found primarily among the nationalistic parties of Central Asia. Tengrism may be interpreted as a Turkic version of Russian neopaganism. A related phenomenon is the revival of Zoroastrianism in Tajikistan.

By 2006, a Tengrist society in Bishkek, an "international scientific centre of Tengrist studies" and a civic group (Tengir Ordo, the "army of Tengri") were established by Kyrgyz businessman and politician Dastan Sarygulov. His ideology incorporated ethnocentrism and Pan-Turkism, but did not receive strong support. After the Kyrgyzstani presidential elections of 2005, Sarygulov became state secretary and set up a work group dealing with ideological issues.[19] Another Kyrgyz proponent of Tengrism, Kubanychbek Tezekbaev, was prosecuted for inciting religious and ethnic hatred in 2011 with statements in an interview describing Kyrgyz mullahs as "former alcoholics and murderers".[20]

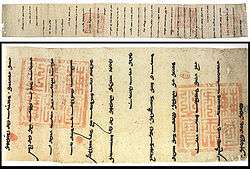

Arghun's letters

Arghun expressed the association of Tengri with imperial legitimacy and military success. The majesty (suu) of the khan is a divine stamp granted by Tengri to a chosen individual through which Tengri controls the world order (the presence of Tengri in the khan). In this letter, "Tengri" or "Mongke Tengri" ("Eternal Heaven") is at the top of the sentence. In the middle of the magnified section, the phrase Tengri-yin Kuchin ("Power of Tengri") forms a pause before it is followed by the phrase Khagan-u Suu ("Majesty of the Khan"):

Under the Power of the Eternal Tengri. Under the Majesty of the Khan (Kublai Khan). Arghun Our word. To the Ired Farans (King of France). Last year you sent your ambassadors led by Mar Bar Sawma telling Us: "if the soldiers of the Il-Khan ride in the direction of Misir (Egypt) we ourselves will ride from here and join you", which words We have approved and said (in reply) "praying to Tengri (Heaven) We will ride on the last month of winter on the year of the tiger and descend on Dimisq (Damascus) on the 15th of the first month of spring." Now, if, being true to your words, you send your soldiers at the appointed time and, worshipping Tengri, we conquer those citizens (of Damascus together), We will give you Orislim (Jerusalem). How can it be appropriate if you were to start amassing your soldiers later than the appointed time and appointment? What would be the use of regretting afterwards? Also, if, adding any additional messages, you let your ambassadors fly (to Us) on wings, sending Us luxuries, falcons, whatever precious articles and beasts there are from the land of the Franks, the Power of Tengri (Tengri-yin Kuchin) and the Majesty of the Khan (Khagan-u Suu) only knows how We will treat you favorably. With these words We have sent Muskeril (Buscarello) the Khorchi. Our writing was written while We were at Khondlon on the sixth khuuchid (6th day of the old moon) of the first month of summer on the year of the cow.

Arghun expressed Tengrism's non-dogmatic side. The name Mongke Tengri ("Eternal Tengri") is at the top of the sentence in this letter to Pope Nicholas IV, in accordance with Mongolian Tengriist writing rules):

... Your saying "May [the Ilkhan] receive silam (baptism)" is legitimate. We say: "We the descendants of Genghis Khan, keeping our own proper Mongol identity, whether some receive silam or some don't, that is only for Eternal Tengri (Heaven) to know (decide)." People who have received silam and who, like you, have a truly honest heart and are pure, do not act against the religion and orders of the Eternal Tengri and of Misiqa (Messiah or Christ). Regarding the other peoples, those who, forgetting the Eternal Tengri and disobeying him, are lying and stealing, are there not many of them? Now, you say that we have not received silam, you are offended and harbor thoughts of discontent. [But] if one prays to Eternal Tengri and carries righteous thoughts, it is as much as if he had received silam. We have written our letter in the year of the tiger, the fifth of the new moon of the first summer month (May 14th, 1290), when we were in Urumi.

Muslim opposition

Turkic worship of Tengri was mocked by the Muslim Turk Mahmud al-Kashgari, who wrote: "The infidels - may God destroy them!"[21][22] According to Kashgari, Muhammad assisted in a miraculous event where 700,000 Yabāqu infidels were defeated by 40,000 Muslims led by Arslān Tegīn; fires shot sparks at the Yabāqu from gates on a green mountain[23] (the Yabaqu were a Turkic people).[24]

Terms for 'shaman' and 'shamaness' in Siberian languages

- 'shaman': saman (Nedigal, Nanay, Ulcha, Orok), sama (Manchu). The variant /šaman/ (i.e., pronounced "shaman") is Evenk (whence it was borrowed into Russian).

- 'shaman': alman, olman, wolmen[25] (Yukagir)

- 'shaman': [qam] (Tatar, Shor, Oyrat), [xam] (Tuva, Tofalar)

- The Buryat word for shaman is бөө (böö) [bøː], from early Mongolian böge.[26]

- 'shaman': ńajt (Khanty, Mansi), from Proto-Uralic *nojta (c.f. Sámi noaidi)

- 'shamaness': [iduɣan] (Mongol), [udaɣan] (Yakut), udagan (Buryat), udugan (Evenki, Lamut), odogan (Nedigal). Related forms found in various Siberian languages include utagan, ubakan, utygan, utügun, iduan, or duana. All these are related to the Mongolian name of Etügen, the hearth goddess, and Etügen Eke 'Mother Earth'. Maria Czaplicka points out that Siberian languages use words for male shamans from diverse roots, but the words for female shaman are almost all from the same root. She connects this with the theory that women's practice of shamanism was established earlier than men's, that "shamans were originally female."[27]

Nestorianism and Tengrism

Tengrism has been called Nestorianism by Christian sources.[28] Turkish Nestorian manuscripts with the same rune-like characters as Old Turkic script have been found in the oasis of Turfan and the fortress of Miran.[29][30][31] It is unknown when and by whom the Bible was first translated into Turkish.[32] Most records in pre-Islamic Central Asia are written in the Old Turkic language.[33] Nestorian Christianity had followers among the Uighurs. In the Nestorian sites of Turfan, a fresco depicting Palm Sunday has been discovered.[34]

Buddhism and Tengrism

The 17th century Mongolian chronicle Altan Tobchi (Golden Summary) contains references to Tengri. Tengrism was assimiliated into Mongolian Buddhism while surviving in purer forms only in far-northern Mongolia. Tengrist formulas and ceremonies were subsumed into the state religion. This is similar to the fusion of Buddhism and Shinto in Japan. The Altan Tobchi contains the following prayer at its very end:

|

|

See also

Notes

- ↑ The spelling Tengrism is found in the 1960s, e.g. Bergounioux (ed.), Primitive and prehistoric religions, Volume 140, Hawthorn Books, 1966, p. 80. Tengrianism is a reflection of the Russian term, Тенгрианство. It is reported in 1996 ("so-called Tengrianism") in Shnirelʹman (ed.), Who gets the past?: competition for ancestors among non-Russian intellectuals in Russia, Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-8018-5221-3, p. 31 in the context of the nationalist rivalry over Bulgar legacy. The spellings Tengriism and Tengrianity are later, reported (deprecatingly, in scare quotes) in 2004 in Central Asiatic journal, vol. 48–49 (2004), p. 238. The Turkish term Tengricilik is also found from the 1990s. Mongolian Тэнгэр шүтлэг is used in a 1999 biography of Genghis Khan (Boldbaatar et. al, Чингис хаан, 1162-1227, Хаадын сан, 1999, p. 18).

- ↑ R. Meserve, Religions in the central Asian environment. In: History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume IV, The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century, Part Two: The achievements, p. 68:

- "[...] The ‘imperial’ religion was more monotheistic, centred around the all-powerful god Tengri, the sky god."

- ↑ Michael Fergus, Janar Jandosova, Kazakhstan: Coming of Age, Stacey International, 2003, p.91:

- "[...] a profound combination of monotheism and polytheism that has come to be known as Tengrism."

- ↑ "There is no doubt that between the 6th and 9th centuries Tengrism was the religion among the nomads of the steppes" Yazar András Róna-Tas, Hungarians and Europe in the early Middle Ages: an introduction to early Hungarian history, Yayıncı Central European University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-963-9116-48-1, p. 151.

- 1 2 Hungarians & Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early... - András Róna-Tas. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ Jean-Paul Roux, Die alttürkische Mythologie, p. 255

- ↑ Saunders, Robert A. and Vlad Strukov (2010). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Federation. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. pp. 412–13. ISBN 978-0-81085475-8.

- ↑ Mehmet Eröz (2010-03-10). Eski Türk dini (gök tanrı inancı) ve Alevîlik-Bektaşilik. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ Fodor István, A magyarok ősi vallásáról (About the old religion of the Hungarians) Vallástudományi Tanulmányok. 6/2004, Budapest, p. 17–19

- ↑ Tekin, Talat (1993). Irk bitig (the book of omens). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-447-03426-5.

- ↑ Balkanlar'dan Uluğ Türkistan'a Türk halk inançları Cilt 1, Yaşar Kalafat, Berikan, 2007

- ↑ McDermott, Roger. "The Jamestown Foundation: High-Ranking Kyrgyz Official Proposes New National Ideology". Jamestown.org. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ Bulgars and the Slavs followed ancestral religious practices and worshipped the sky-god Tengri. Bulgaria, Patriarchal Orthodox Church of --, p. 79, at Google Books

- ↑ Buddhist studies review, Volumes 6-8, 1989, p. 164.

- ↑ Osman Turan, The Ideal of World Domination among the Medieval Turks, in Studia Islamica, No. 4 (1955), pp. 77-90

- ↑ Hutton 2001. p. 32.

- ↑ Hoppál, Mihály (2005). Sámánok Eurázsiában (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-8295-3. pp. 77, 287; Znamensky, Andrei A. (2005). "Az ősiség szépsége: altáji török sámánok a szibériai regionális gondolkodásban (1860–1920)". In Molnár, Ádám. Csodaszarvas. Őstörténet, vallás és néphagyomány. Vol. I (in Hungarian). Budapest: Molnár Kiadó. pp. 117–134. ISBN 963-218-200-6. , p. 128

- ↑ Irina S. Urbanaeva (Урбанаева И.С.), Шаманизм монгольского мира как выражение тенгрианской эзотерической традиции Центральной Азии ("Shamanism in the Mongolian World as an Expression of the Tengrianist Esoteric Traditions of Central Asia"), Центрально-азиатский шаманизм: философские, исторические, религиозные аспекты. Материалы международного симпозиума, 20-26 июня 1996 г., Ulan-Ude (1996); English language discussion in Andrei A. Znamenski, Shamanism in Siberia: Russian records of indigenous spirituality, Springer, 2003, ISBN 978-1-4020-1740-7, 350–352.

- ↑ Erica Marat, Kyrgyz Government Unable to Produce New National Ideology, 22 February 2006, CACI Analyst, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute.

- ↑ RFE/RL 31 January 2012.

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ↑ Dankoff, Robert (Jan–Mar 1975). "Kāšġarī on the Beliefs and Superstitions of the Turks". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 95 (1): 70. doi:10.2307/599159. JSTOR 599159.

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ↑ Mehmet Fuat Köprülü; Gary Leiser; Robert Dankoff (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Psychology Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-0-415-36686-1.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 January 2001. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ Lessing, Ferdinand D., ed. (1960). Mongolian-English Dictionary. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 123.

- ↑ Czaplicka, Maria (1914). "XII. Shamanism and Sex". Aboriginal Siberia. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ A. S. Amanjolov, History of ancient Türkic Script, Almaty 2003, p.305

- ↑ University of Bonn. Department of Linguistics and Cultural Studies of Central Asia, Issue 37, VGH Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH Publishing, 2008, p.107

- ↑ Jens Wilkens, Wolfgang Voigt, Dieter George, Hartmut-Ortwin Feistel, German Oriental Society, List of Oriental Manuscripts in Germany, Volume 12, Franz Steiner Publishing, 2000, p.480

- ↑ Volker Adam, Jens Peter Loud, Andrew White, Bibliography old Turkish Studies, Otto Harrassowitz Publishing, 2000, p.40

- ↑ Materialia Turcica, Volumes 22-24, Brockmeyer Publishing Studies, 2001, p.127

- ↑ "Turfan research: Scripts and languages in pre-Islamic Central Asia, Academy of Sciences of Berlin and Brandenburg, 2011" (in German). Bbaw.de. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ M. S. Asimov, The historical,social and economic setting, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1999, p.204

References

- Brent, Peter (1976). The Mongol Empire: Genghis Khan: His Triumph and his Legacy. London: Book Club Associates.

- Richtsfeld, Bruno J. (2004). "Rezente ostmongolische Schöpfungs-, Ursprungs- und Weltkatastrophenerzählungen und ihre innerasiatischen Motiv- und Sujetparallelen". Münchner Beiträge zur Völkerkunde. Jahrbuch des Staatlichen Museums für Völkerkunde München. 9. pp. 225–274.