Religion in France

Religion in France can attribute its diversity to the country's adherence to freedom of religion and freedom of thought, as guaranteed by the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The Republic is based on the principle of laïcité (or "freedom of conscience") enforced by the 1880s Jules Ferry laws and the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State. Catholicism, the religion of a now small majority of French people, is no longer the state religion that it was before the French Revolution, as well as throughout the various, non-republican regimes of the 19th century (the Restoration, the July Monarchy and the Second French Empire).

Major religions practised in France include the Catholic Church, Islam, various branches of Protestantism, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Russian Orthodoxy, Armenian Christianity, and Sikhism amongst others, making it a multiconfessional country. Sunday mass attendance has fallen to 5% for the Catholics, and the overall level of observance is considerably lower than in the past.[2][3] According to a Eurobarometer survey conducted in 2010, 27% of French citizens responded that they "believe there is a God", 27% answered that they "believe there is some sort of spirit or life force", and 40% answered that they "do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force". This makes France one of the most irreligious countries in the world.[4]

Demographics

Chronological statistics

| Religious group |

Population % 1986[5] |

Population % 1994[5] |

Population % 2007[6] |

Population % 2016[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

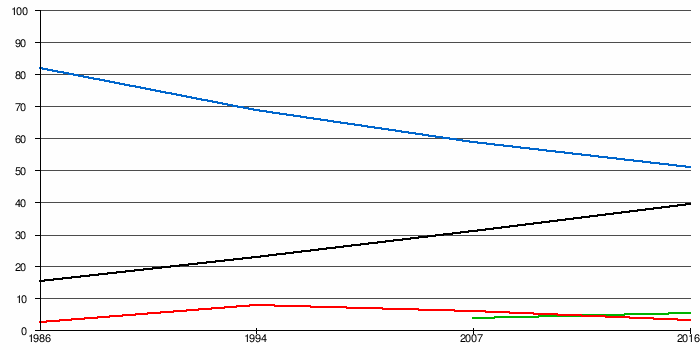

| Christianity | 82% | 69% | 59% | 51.1% |

| –Catholicism | 81% | 67% | 51% | - |

| –Protestantism | 1% | 2% | 3% | - |

| –Other and unaffiliated Christians | - | - | 5% | - |

| Islam | - | - | 4% | 5.6% |

| Judaism | - | - | 1% | 0.8% |

| Other religions and unspecified | 2.5% | 8% | 5% | 2.5% |

| Not religious | 15.5% | 23% | 31% | 39.6% |

Line chart

Religion among the youth

In 2018, a study by the French polling agency OpinionWay, based on a sample of 1.000, found that 41% of 18 to 30 years old Frenchmen declared themselves as Catholics, 3% as Protestants, 8% as Muslim, 1% were Buddhists, 1% were Jews and 3% were affiliated with other religions, 43% regarded themselves as unaffiliated. Regarding their belief of God, 52% believed that the existence of God to be certain or probable, whilst 28% believed it to be improbable and 19% regarded it as excluded.[7]

In the same year, according to a study jointly conducted by London's St Mary's University's Benedict XVI Centre for Religion and Society and the Institut Catholique de Paris, and based on data from the European Social Survey 2014–2016, collected on a sample of 600, among 16 to 29 years-old Frenchmen 25% were Christians (23% Catholic and 2% Protestant), 10% were Muslims, 1% were of other religions, and 64% were not religious.[8] The data was obtained from two questions, one asking "Do you consider yourself as belonging to any particular religion or denomination?" to the full sample and the other one asking "Which one?" to the sample who replied with "Yes".[9]

History

France guarantees freedom of religion as a constitutional right and the government generally respects this right in practice. A tradition of anticlericalism led the state to break its ties to the Catholic Church in 1905. adopted a strong commitment to maintaining a totally secular public sector.[10]

Catholicism as a state religion

Catholicism is the largest religion in France. During the pre-1789 Ancien Régime, France was traditionally considered the Church's eldest daughter, and the King of France always maintained close links to the Pope. However, the "Gallicanism" principle meant that the king selected bishops.

French Wars of Religion (1562–1598)

A strong Protestant population resided in France, primarily of Reformed confession. It was persecuted by the state for most of the time, with temporary periods of relative toleration. These wars continued throughout the 16th century, with the 1572 St. Bartholomew's Day massacre as its apex, until the 1598 Edict of Nantes issued by Henry IV.

For the first time, Huguenots were considered by the state as more than mere heretics. The Edict of Nantes thus opened a path for secularism and tolerance. In offering general freedom of conscience to individuals, the edict offered many specific concessions to the Protestants, for instance, amnesty and the reinstatement of their civil rights, including the right to work in any field or for the State and to bring grievances directly to the king.[11]

Post–Edict of Nantes (1598–1789)

The 1598 Edict also granted the Protestants fifty places of safety (places de sûreté), which were military strongholds such as La Rochelle for which the king paid 180,000 écus a year, along with a further 150 emergency forts (places de refuge), to be maintained at the Huguenots' own expense. Such an innovative act of toleration stood virtually alone in a Europe (except for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) where standard practice forced the subjects of a ruler to follow whatever religion that the ruler formally adopted – the application of the principle of cuius regio, eius religio.

Religious conflicts resumed in the end of the 17th century, when Louis XIV, the "Sun King", initiated the persecution of Huguenots by introducing the dragonnades in 1681. This wave of violence intimidated the Protestants into converting to Catholicism. He made the policy official with the 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes. As a result, a large number of Protestants – estimates range from 200,000 to 500,000 – left France during the following two decades, seeking asylum in England, the United Provinces, Denmark, in the Protestant states of the Holy Roman Empire (Hesse, Brandenburg-Prussia, etc.), and European colonies in North America and South Africa.[12]

The 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes created a state of affairs in France similar to that of virtually every other European country of the period, where only the majority state religion was tolerated. The experiment of religious toleration in Europe was effectively ended for the time being. In practice, the revocation caused France to suffer a brain drain, as it lost a large number of skilled craftsmen, including key designers such as Daniel Marot.[13]

French Revolution

During the French Revolution, the Catholic Church was stripped of most of its wealth, its power and influence.[14] The early revolutionaries sought to secularize all of French society, an effort inspired by the writings and philosophy of Voltaire.[15] In August 1789, the new National Assembly abolished tithes, the mandatory 10% tax paid to the Catholic Church. In November 1789, they voted to expropriate the vast wealth of the Church in endowments. lands and buildings.[16] In 1790, the Assembly abolished monastic religious orders. Statues and saints were rejected in a burst of iconoclasm, and most religious instruction ended.[17]

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy of 1790, put the Catholic Church under state control. It required priests and bishops to be elected by French people, which usurped the traditional authority of the Church. The Republic legalized divorce and transferred the powers of birth, death, and marriage registration to the state.[16] The Catholic clergy was persecuted by the commune of Paris and by some of the representatives on mission. Most notably, Jean-Baptiste Carrier conducted large-scale drownings of priests and nuns in the river Loire.[18]

In 1793, the government established a secular Republican calendar to erase memory of Sundays, saint days and religious holidays. Traditionally, every seventh day – Sunday – was a day of rest, together with numerous other days for celebration and relaxation. The government tried to end all that; the new calendar only allowed one day in 10 for relaxation. Workers and peasants felt cheated and overworked. The new system disrupted daily routines, reduced work-free days and ended favorite celebrations. When the reformers were overthrown or executed, their radical new calendar was quickly abandoned.[19][20]

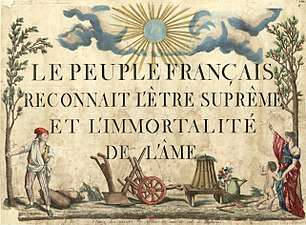

Religious minorities—Protestants and Jews—were granted full civil and political rights, which represented a shift towards a more secular government to some, and an attack on the Catholic Church to others.[16] New religions and philosophies were allowed to compete with Catholicism. The introduction of the prominent cults during the revolutionary period – the Cult of Reason and the Cult of the Supreme Being – responded to the belief that religion and politics should be seamlessly fused together. This is a shift from the original Enlightenment ideals of the Revolution that advocated for a secular government with tolerance for various religious beliefs.[21] While Maximilien Robespierre favored a religious foundation to the Republic, he maintained a hard stance against Catholicism because of its association with corruption and the counterrevolution.[16]

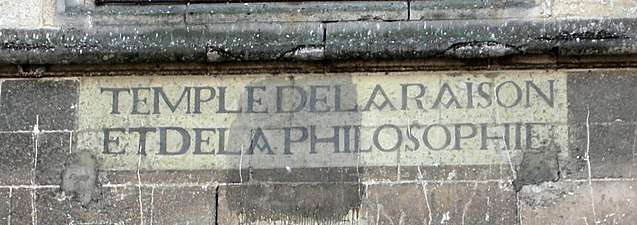

The cults sought to erase the old ways of religion by closing churches, confiscating church bells, and implementing a new Republican Calendar that excluded any days for religious practice. Many churches were converted into Temples of Reason. The Cult of Reason was first to de-emphasize the existence of God, and instead focus on deism, featuring not the sacred, divine, nor eternal, but the natural, earthy, and temporal existence.[21] To tie the church and the state together, the cults transformed traditional religious ideology into politics. The Cult of the Supreme Being used religion as political leverage. Robespierre accused political opponents as hiding behind God and using religion to justify their oppositional stance against the Revolution. It was a shift in ideology that allowed for the cult to use the new deistic beliefs for political momentum.[21]

Following the Thermidorian Reaction the persecutions of Catholic clergy ceased and the role of new cults practically ended.

Standard of the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being, one of the proposed state religions to replace Christianity in revolutionary France.

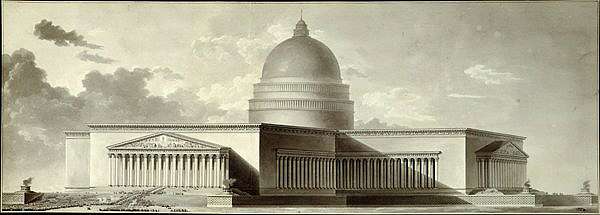

Standard of the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being, one of the proposed state religions to replace Christianity in revolutionary France. Project for the never-built Métropole, which had to be the main church of the Cult of the Supreme Being.

Project for the never-built Métropole, which had to be the main church of the Cult of the Supreme Being. Many Catholic churches were turned into Temples of Reason during the Revolution, as recalled by this inscription on a church in Ivry-la-Bataille. The Cult of Reason was an atheistic alternative to the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being.

Many Catholic churches were turned into Temples of Reason during the Revolution, as recalled by this inscription on a church in Ivry-la-Bataille. The Cult of Reason was an atheistic alternative to the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being.

Napoleon and concordat with the Vatican

The Catholic Church was badly hurt by the Revolution.[22] By 1800 it was poor, dilapidated and disorganized, with a depleted and aging clergy. The younger generation had received little religious instruction, and was unfamiliar with traditional worship. However, in response to the external pressures of foreign wars, religious fervor was strong, especially among women.[23]

Napoleon took control by 1800 and realized that religious divisiveness had to be minimized to unite France. The Concordat of 1801 was an agreement between Napoleon and Pope Pius VII, signed in July 1801 that remained in effect until 1905. It sought national reconciliation between revolutionaries and Catholics and solidified the Roman Catholic Church as the majority church of France, with most of its civil status restored. The hostility of devout Catholics against the state had then largely been resolved. It did not restore the vast church lands and endowments that had been seized upon during the revolution and sold off. Catholic clergy returned from exile, or from hiding, and resumed their traditional positions in their traditional churches. Very few parishes continued to employ the priests who had accepted the Civil Constitution of the Clergy of the Revolutionary regime. While the Concordat restored much power to the papacy, the balance of church-state relations tilted firmly in Napoleon's favour. He selected the bishops and supervised church finances.[24]

Bourbon Restoration (1814-1830)

With the Bourbon Restoration and the Catholic Church again became the state religion of France. Other religion was tolerated, but Catholicism was favored financially and politically. Its lands and Financial endowments were not returned, But now the government paid salaries and maintenance costs for normal church activities. The bishops had regained control of Catholic affairs. The aristocracy before the Revolution did not place a high priority on religious doctrine or practice, the decades of exile created an alliance of throne and altar. The royalists who returned were much more devout, and much more aware of their need for a close alliance with the Church. They had discarded fashionable skepticism and now promoted the wave of Catholic religiosity that was sweeping Europe, with a new regard to the Virgin Mary, the Saints, and popular religious rituals such as saying the rosary. Devotionalism and was far stronger in rural areas, and much less noticeable in Paris and the other cities. The population of 32 million included about 680,000 Protestants, and 60,000 Jews. They were tolerated. Anti-clericalism of the sort promoted by the Enlightenment and writers such as Voltaire had not disappeared, but it was in recession.[25]

At the elite level, there was a dramatic change in intellectual climate from the dry intellectually oriented classicism to emotionally based romanticism. A book by François-René de Chateaubriand entitled Génie du christianisme ("The Genius of Christianity") (1802) had an enormous influence in reshaping French literature and intellectual life. The book emphasized the power of religion in creating European high culture. Chateaubriand’s book:

- did more than any other single work to restore the credibility and prestige of Christianity in intellectual circles and launched a fashionable rediscovery of the Middle Ages and their Christian civilisation. The revival was by no means confined to an intellectual elite, however, but was evident in the real, if uneven, rechristianisation of the French countryside.[26]

Napoleon III 1848-1870

Napoleon III was a strong supporter of Catholic interest, such as financing, and support for Catholic missionaries in the emerging French Empire. his primary goal was conciliation of all the religious and anti-religious interests in France, to avoid the furious hatreds and battles that took place during the revolution, and that would reappear after he left office.[27][28]

In foreign policy, he was the leading supporter of the Pope, especially against the anti-clerical Kingdom of Italy that emerged in 1860, took control of parts of the papal states, and sought to take complete control of Rome. The French army prevented that. In Paris, the Emperor was supported the conservative Gallican bishops to minimize the people role inside France, in the liberal Catholic intellectuals who wanted to use the Church as an instrument of reform. Problem came with Pope Pius IX who reigned 1846 to 1878. He began as a liberal, but suddenly in the 1860s became the leading champion of reactionary politics in Europe, in opposition to all forms of modern liberalism. He demanded complete autonomy for the church and religious and educational affairs, and had the First Vatican Council (1869–70) decree papal infallibility. Napoleon III was too committed in foreign-policy to the support of Rome to break with the Pope, but that alliance seriously weakened him at home. When he declared war on Prussia in 1870, he brought his army home, and the kingdom of Italy swallowed up the papal domains and the Pope became the prisoner of the Vatican. Vatican statements attacking progress, industrialization, capitalism, socialism, and virtually every new idea not only angered them liberal and conservative Catholic elements in France, but energized the secular liberals (including many professionals) and anti-clerical socialist movement; they escalated their attacks on church schools.[29]

Third Republic (1870–1940)

Throughout the lifetime of the Third Republic (1870–1940), there were battles over the status of the Catholic Church in France among the republicans, monarchists and the authoritarians (such as the Napoleonists). The French clergy and bishops were closely associated with the monarchists and many of its hierarchy were from noble families. Republicans were based in the anti-clerical middle class, who saw the Church's alliance with the monarchists as a political threat to republicanism, and a threat to the modern spirit of progress. The republicans detested the Church for its political and class affiliations; for them, the Church represented the Ancien Régime, a time in French history most republicans hoped was long behind them. The republicans were strengthened by Protestant and Jewish support. Numerous laws were passed to weaken the Catholic Church. In 1879, priests were excluded from the administrative committees of hospitals and boards of charity; in 1880, new measures were directed against the religious congregations; from 1880 to 1890 came the substitution of lay women for nuns in many hospitals; in 1882, the Ferry school laws were passed. Napoleon's Concordat of 1801 continued in operation, but in 1881, the government cut off salaries to priests it disliked.[30]

Republicans feared that religious orders in control of schools—especially the Jesuits and Assumptionists—indoctrinated anti-republicanism into children. Determined to root this out, republicans insisted they needed control of the schools for France to achieve economic and militaristic progress. (Republicans felt one of the primary reasons for the German victory in 1870 was their superior education system.)

The early anti-Catholic laws were largely the work of republican Jules Ferry in 1882. Religious instruction in all schools was forbidden, and religious orders were forbidden to teach in them. Funds were appropriated from religious schools to build more state schools. Later in the century, other laws passed by Ferry's successors further weakened the Church's position in French society. Civil marriage became compulsory, divorce was introduced, and chaplains were removed from the army.[31]

When Leo XIII became pope in 1878, he tried to calm Church-State relations. In 1884, he told French bishops not to act in a hostile manner toward the State ('Nobilissima Gallorum Gens'[32]). In 1892, he issued an encyclical advising French Catholics to rally to the Republic and defend the Church by participating in republican politics ('Au milieu des sollicitudes'[33]). This attempt at improving the relationship failed. Deep-rooted suspicions remained on both sides and were inflamed by the Dreyfus Affair (1894–1906). Catholics were for the most part anti-Dreyfusard. The Assumptionists published anti-Semitic and anti-republican articles in their journal La Croix. This infuriated republican politicians, who were eager to take revenge. Often they worked in alliance with Masonic lodges. The Waldeck-Rousseau Ministry (1899–1902) and the Combes Ministry (1902–05) fought with the Vatican over the appointment of bishops. Chaplains were removed from naval and military hospitals in the years 1903 and 1904, and soldiers were ordered not to frequent Catholic clubs in 1904.

Emile Combes, when elected Prime Minister in 1902, was determined to defeat Catholicism thoroughly. After only a short while in office, he closed down all parochial schools in France. Then he had parliament reject authorisation of all religious orders. This meant that all fifty-four orders in France were dissolved and about 20,000 members immediately left France, many for Spain.[34] The Combes government worked with Masonic lodges to create a secret surveillance of all army officers to make sure that devout Catholics would not be promoted. Exposed as the Affaire Des Fiches, the scandal undermined support for the Combes government, and he resigned. It also undermined morale in the army, as officers realized that hostile spies examining their private lives were more important to their careers than their own professional accomplishments.[35]

1905: Separation of Church and State

Radicals (as they called themselves) achieved their main goals in 1905: they repealed Napoleon's 1801 Concordat. Church and State were finally separated. All Church property was confiscated. Religious personnel were no longer paid by the State. Public worship was given over to associations of Catholic laymen who controlled access to churches. However, in practice, masses and rituals continued to be performed.[36]

A 1905 law instituted the separation of Church and State and prohibited the government from recognising, salarying, or subsidising any religion. The 1926 Briand-Ceretti Agreement subsequently restored for a while a formal role for the state in the appointment of Catholic bishops, but evidence for its exercise is not easily obtained. Prior to 1905, the 1801–1808 Concordat compelled the State to support the Catholic Church, the Lutheran Church, the Calvinist Church, and the Jewish religion, and to fund public religious education in those established religions.

For historical reasons, this situation is still current in Alsace-Moselle, which was a German region in 1905 and only joined France again in 1918. Alsace-Moselle maintains a local law of pre-1918 statutes which include the Concordat: the national government salaries as state civil servants the clergy of the Catholic diocese of Metz and of Strasbourg, of the Lutheran Protestant Church of Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine, of the Protestant Reformed Church of Alsace and Lorraine, and of the three regional Israelite consistories, and it provides for now non-compulsory religious education in those religions in public schools and universities. For also historical reasons, Catholic priests in French Guiana are civil servants of the local government.

Religious buildings built prior to 1905 at taxpayers' expense are retained by the local or national government, and may be used at no expense by religious organisations. As a consequence, most Catholic churches, Protestant temples, and Jewish synagogues are owned and maintained by the government. The government, since 1905, has been prohibited from funding any post-1905 religious edifice, and thus religions must build and support all newer religious buildings at their own expense. Some local governments de facto subsidise prayer rooms as part of greater "cultural associations".

Recent tensions

An ongoing topic of controversy is whether the separation of Church and State should be weakened so that the government would be able to subsidise Muslim prayer rooms and the formation of imams. Advocates of such measures, such as Nicolas Sarkozy at times, declare that they would encourage the Muslim population to better integrate into the fabric of French society. Opponents contend that the state should not fund religions. Furthermore, the state ban on wearing conspicuous religious symbols, such as the Islamic female headscarf, in public schools has alienated some French Muslims, provoked minor street protests and drawn some international criticism.

In the late 1950s after the close of the Algerian war, hundreds of thousands of Muslims, including some who had supported France (Harkis), settled permanently to France. They went to the larger cities where they lived in subsidized public housing, and suffered very high unemployment rates.[37] In October 2005, the predominantly Arab-immigrant suburbs of Paris, Lyons, Lille, and other French cities erupted in riots by socially alienated teenagers, many of them second- or third-generation immigrants.[38][39]

American University professor C. Schneider says:

For the next three convulsive weeks, riots spread from suburb to suburb, affecting more than three hundred towns....Nine thousand vehicles were torched, hundreds of public and commercial buildings destroyed, four thousand rioters arrested, and 125 police officers wounded.[40]

Traditional interpretations say these race riots were spurred by radical Muslims or unemployed youth. Another view states that the riots reflected broader problem of racism and police violence in France.[40]

In March 2012, a Muslim radical named Mohammed Merah shot three French soldiers and four Jewish citizens, including children in Toulouse and Montauban.

In January 2015, the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo that had ridiculed the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, and a neighborhood Jewish grocery store came under attack from radicalized Muslims who had been born and raised in the Paris region. World leaders rally to Paris to show their support for free speech. Analysts agree that the episode had a profound impact on France. The New York Times summarized the ongoing debate:

So as France grieves, it is also faced with profound questions about its future: How large is the radicalized part of the country's Muslim population, the largest in Europe? How deep is the rift between France's values of secularism, of individual, sexual and religious freedom, of freedom of the press and the freedom to shock, and a growing Muslim conservatism that rejects many of these values in the name of religion?[41]

Religions

Buddhism

As of the 2000s Buddhism in France was estimated to have between 1 million (Ministry of the Interior) strict adherents and 5 million people influenced by Buddhist doctrines,[42] very large numbers for a Western country. Many French Buddhists do not consider themselves "religious".[43] According to scholar Dennis Gira, who was the director of the Institute of Science and Theology of Religions of Paris, Buddhism in France has a missionary nature and is undergoing a process of "inculturation" that may represent a new turning of the "Wheel of the Dharma", similar to those that it underwent in China and Japan, from which a new incarnation of the doctrine — a "French Buddhism" — will possibly arise.[42]

About 2% of the working-age, internet connected population of France declared they were Buddhists in 2016.[44] In 2012, the European headquarters of the Fo Guang Shan monastic order opened in France, near Paris. It was the largest Buddhist temple in Europe at that time.[45]

Dashang Kagyu Ling in La Boulaye, Saône-et-Loire.

Dashang Kagyu Ling in La Boulaye, Saône-et-Loire. Monks praying at a stupa at Dhagpo Kagyu Ling in Saint-Léon-sur-Vézère, Dordogne.

Monks praying at a stupa at Dhagpo Kagyu Ling in Saint-Léon-sur-Vézère, Dordogne.

Christianity

According to a survey held by Institut français d'opinion publique (Ifop) for the Institut Montaigne think-tank, 51.1% of the total population of France was Christian in 2016.[1] The following year, a survey by Ipsos focused on Protestants and based on 31,155 interviews found that 57.5% of the total population of France declared to be Catholic and 3.1% declared to be Protestant.[46]

In 2016, Ipsos Global Trends, a multi-nation survey held by Ipsos and based on approximately 1,000 interviews, found that Christianity is the religion of 45% of the working-age, internet connected population of France; 42% stated they were Catholic, 2% stated that they were Protestants, and 1% declared to belong to any Orthodox church.[44]

Catholicism

Early Christianity was already present among the Gauls by the 2nd century; Irenaeus, bishop of Lugdunum (Lyon), detailed the deaths of ninety-year-old bishop Pothinus and other martyrs during the persecution in Lyon which took place in 177. The Gaulish church was soon established in communion with the bishop of Rome. With the Migration Period of the Germanic peoples, the Gauls were invaded by the Franks, who at first practised Frankish paganism. Their tribes were unified into a kingdom, which came to be called France, by Clovis I. He was proclaimed the king of the Franks in 509, after having been baptised in 496 by Remigius, bishop of Reims. Roman Catholicism was made the state religion of France. This made the Franks the only Germanic people who directly converted from their paganism to Roman Catholicism without first embracing Arianism, which was the first religion of choice among Germanic peoples in the Migration Period.

In 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, forming the unified political and religious foundation of Christendom, medieval European Christian civilisation, and establishing in earnest France's long historical association with the Catholic Church, for which it was known as the "eldest daughter of the church" throughout the Middle Ages.[47] The French Revolution (1789–1790), which resulted in the establishment of the French First Republic (1792–1804), involved a heavy persecution of the Catholic Church, within a policy of dechristianisation, which led to the destruction of many churches, religious orders and artworks, including the very influential Cluny Abbey. During the First French Empire (1804–1814), the Bourbon Restoration (1814–1830) and the following July Monarchy (1830–1848), Roman Catholicism was made again the state religion, and maintained its role as the de facto majority religion during the Second French Republic (1848–1852) and the Second French Empire (1852–1870). Laïcité (secularism), absolute neutrality of the state with respect to religious doctrines, was first established during the Third French Republic (1870–1940), codified with the 1905 Law on the Separation of Church and State, and remains the official policy of the contemporary French republic.[47]

In a 2016 study sponsored by two Catholic newspapers, the scholars Cleuziou and Cibois estimated that Catholics represented 53.8% of the French population. According to the same study, 23.5% were engaged Catholics and 17% were practising Catholics.[48] The following year, in a survey focused on Protestantism, 57.5% of a sample of 31,155 people declared to be Catholic.[46]

The Reims Cathedral, built on the site where Clovis I was baptised by Remigius, functioned as the site for the coronation of the Kings of France.

The Reims Cathedral, built on the site where Clovis I was baptised by Remigius, functioned as the site for the coronation of the Kings of France..jpg) Interior of the Basilica of Saint Denis in Paris, prototype of Gothic architecture.

Interior of the Basilica of Saint Denis in Paris, prototype of Gothic architecture. The Cluny Abbey in Saône-et-Loire, former centre of the Benedectine Order. During the French Revolution it was largely destroyed and only approximately one-tenth (the tower on the right) remains of the original building, which was the largest church building in medieval Europe, surpassed only by St. Peter's Basilica in the 17th century.

The Cluny Abbey in Saône-et-Loire, former centre of the Benedectine Order. During the French Revolution it was largely destroyed and only approximately one-tenth (the tower on the right) remains of the original building, which was the largest church building in medieval Europe, surpassed only by St. Peter's Basilica in the 17th century. The former Royal Abbey of Our Lady of Fontevraud in Maine-et-Loire, now Centre Culturel de l'Ouest.

The former Royal Abbey of Our Lady of Fontevraud in Maine-et-Loire, now Centre Culturel de l'Ouest.

Protestantism

According to a survey by Ifop, in 2012 770 people out of the 37,743 interviewed (or 2.1%) declared to be Protestants of various types. About 42% of them were Calvinists (Huguenots), 21% were evangelical Protestants, 17% were Lutherans and another 20% were affiliated with other Protestant churches.[49] The percentage rose to 3.1% in 2017, mainly due to recent conversions. Out of 100% of people that have become Protestants, 67% were Catholic and 27% were of no religion.[46]

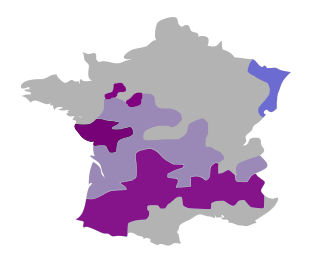

In a study regarding the various religions of France, based on 51 surveys held by the Ifop in the period 2011-2014, so based on a sample of 51.770 interviewed, there were 17.4% of Protestants in the Bas-Rhin, 7.3% in the Haut-Rhin, 7.2% in the Gard, 6.8% in the Drôme and 4.2% in the Ardèche. In the other departments this presence is residual, with, for example, only 0.5% in Côte-d'Or and in the Côtes-d'Armor.[50]

- Lutheran church of Sarreguemines, Moselle.

- Lutheran church of Wangen, Bas-Rhin.

Orthodox Christianity

Eastern Orthodoxy

.jpg)

The Eastern Orthodox Church in France is represented by several communities and ecclesiastical jurisdictions. Traditionally, Eastern Orthodox Christians in France are mainly ethnic Greeks, Russians, Romanians, Bulgarians, Serbs and Georgians, but there are also some ethnic French converts to Eastern Orthodoxy. Different Eastern Orthodox churches have separate jurisdictions and organisations in France, the oldest among them being the Greek Orthodox Metropolis of France under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[51]

Oriental Orthodoxy

Oriental Orthodox Christianity in France is represented by several communities and ecclesiastical jurisdictions. Traditionally, Oriental Orthodox Christians in France are mainly ethnic Armenians, Copts, Ethiopians and Syriacs, but there are also French converts. The largest Oriental Orthodox church in France is the French Coptic Orthodox Church.[52]

Other Christians

Other Christian groups in France include the Jehovah's Witnesses, the Mormons, and other small sects. The European Court on Human Rights reckoned 249,918 "regular and occasional" Jehovah's Witnesses in France[53] and according to their official website, there are 128,759 ministers who teach the Bible in the country.[54]

Islam

A 2016 survey held by Institut Montaigne and Ifop found that 6.6% of the French population had an Islamic background, while 5.6% declared they were Muslims by faith. According to the same survey, 84.9% of the French people who had an Islamic background were still Muslims, 3.4% were Christians, 10.0% were not religious and 1.3% belonged to other religions.[1]

In the same year, Ipsos found that just 2% of the working-age, internet connected French declared they were Muslims.[44] This gap is most likely due to the difference of the samples, since the survey held by the Institut Montaigne and the Institut français d'opinion publique has a total sample of 15,459 people, while the Ipsos Global Trends survey has a sample of only about 1,000, so the margin of error is bigger.

Omar ibn Al Khattab Mosque in Saint-Martin-d'Hères, Isère.

Omar ibn Al Khattab Mosque in Saint-Martin-d'Hères, Isère.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Judaism

In 2016, 0.8% of the total population of France, or about 535.000 people, were religious Jews.[1] There has been a Jewish presence in France since at least the early Middle Ages. France was a center of Jewish learning in the Middle Ages, but persecution increased as the Middle Ages wore on, including multiple expulsions and returns. During the late 18th-century French Revolution, France was the first country in Europe to emancipate its Jewish population. Antisemitism persisted despite legal equality, as expressed in the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century.

During World War II, the Vichy government collaborated with Nazi occupiers to deport numerous French and foreign Jewish refugees to concentration camps.[55] 75% of the Jewish population in France nonetheless survived the Holocaust.[56][57]

_la_synagogue_47.jpg)

Synagogue of Wolfisheim, Bas-Rhin.

Synagogue of Wolfisheim, Bas-Rhin. Synagogue of Colmar, Haut-Rhin.

Synagogue of Colmar, Haut-Rhin.

Paganism

Paganism, in the sense of contemporary Neopaganism, in France has been described as twofold, on one side represented by ethnically identitary religious movements and on the other side by a variety of witchcraft and shamanic traditions without ethnic connotations. According to the French historian of ideas and far-right ideologies Stéphane François, the term "pagan" (Latin paganus), used by Christians to define those who maintained polytheistic religions, originally meant "countryman" in the sense of "citizen", the "insiders" (inside the cultural tradition or citizenry), and its opposite term was "alien" (Latin alienus), the "others", the "outsiders", which defined Christians. Modern French Pagans of the identitary movements hearken back to this meaning.[58]

Identitary Pagan movements are the majority and are represented by Celtic Druidry and Germanic Heathenry, many of whom uphold the idea of a superiority of the white race and of the Indo-Europeans. They are aligned with the Nouvelle Droite political movement, espousing the idea that each ethnically-defined folk has its own natural land and natural religion. The identitary Pagan movement carries within itself a warrior ethic which is concerned with the erosion of French and European culture under growing immigration and Islamisation, so that Jean Haudry, longtime identitary Pagan and professor of linguistics at Lyon III, in a 2001 article entitled Païens ! for the journal of the organisation Terre et Peuple says that "Pagans will be at the forefront of the reconquest (of Europe)". Dominique Venner, who committed suicide in 2013 inside Notre-Dame de Paris in protest against the erosion of French culture, was a Pagan[58] close to the Groupement de recherche et d'études pour la civilisation européenne (GRECE), an identitary Pagan think-tank founded by the Nouvelle Droite ideologist Alain de Benoist. Other politically-engaged Pagans include Pierre Vial, who with other members of the National Front was among the founders of Terre et Peuple.[58]

Other religions

According to the French sociologist Régis Dericquebourg, in 2003 the main small religious minorities were the Jehovah's Witnesses (130,000, though the European Court on Human Rights reckoned the number at 249,918 "regular and occasional" Jehovah's Witnesses),[53] Adventists, Evangelicals, Mormons (31,000 members), Scientologists (4,000), and Soka Gakkai Buddhists. According to the 2005 Association of Religion Data Archives data there were close to 4,400 Bahá'ís in France.[59] According to the 2007 edition of the Quid, other notable religious minorities included the New Apostolic Church (20,000), the Universal White Brotherhood (20,000), Sukyo Mahikari (15,000–20,000), the New Acropolis (10,000), the Universal Alliance (1,000), and the Grail Movement (950).[60]

Many groups have around 1,000 members, including Antoinism, Aumism, Christian Science, Invitation to Life, Raelism, and the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, while the Unification Church has around 400 members. In 1995, France created the first French parliamentary commission on cult activities which led to a report registering a number of religious groups considered as socially disruptive and/or dangerous. Some of these groups have been banned, including the Children of God.[61]

New Mayapur Temple of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness in Luçay-le-Mâle, Indre.

New Mayapur Temple of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness in Luçay-le-Mâle, Indre. Statue of a Chinese goddess during a procession for the Chinese New Year in Paris.

Statue of a Chinese goddess during a procession for the Chinese New Year in Paris. Antoinist temple of Tours, Indre-et-Loire.

Antoinist temple of Tours, Indre-et-Loire.

Controversies and incidents

Growth of Islam and conflict with laïcité

In Paris and the surrounding Île-de-France region French Muslims tend to be more educated and religious, and the vast majority of them rejects violence and say they are loyal to France.[62][63] Among Muslims in Paris, in the early 2010s, 77% disagreed when asked whether violence is an acceptable moral response for a noble cause or not; 73% said that they were loyal to France; and 18% believed homosexuality to be acceptable.[62]

In 2015 there were 2,500 mosques in France, up from 2,000 in 2011. In 2015, Dalil Boubakeur, rector of the Grand Mosque of Paris, said the number should be doubled to accommodate the large and growing population of French Muslims.[64]

Financing to the construction of mosques was a problematic issue for a long time; French authorities were concerned that foreign capital could be used to acquire influence in France and so in the late 1980s it was decided to favour the formation of a "French Islam", though the 1905 law on religions forbids the funding of religious groups by the state. According to Salah Bariki, advisor to the mayor of Marseille in 2001, at a Koranic school in Nièvre only three percent of the books were written in French and everything was financed from abroad. She supported the public participation in financing an Islamic cultural centre in Marseille to encourage Muslims to develop and use French learning materials, in order to thwart foreign indoctrination. Even secular Muslims and actors of civil society were to be represented by the centre.[65] Local authorities have financed the construction of mosques, sometimes without minarets and calling them Islamic "cultural centres" or municipal halls rented to "civil associations". In the case of the plans to build the Mosque of Marseille, due to protests and tribunal decision by the National Rally, the National Republican Movement, and the Mouvement pour la France, the rent of a 8,000 m2 (86,111 sq ft) terrain for the mosque was increased from €300/year to €24,000/year and the renting period was reduced from 99 to 50 years.[65]

Charlie Hebdo shooting

After the shooting at the Charlie Hebdo satirical newspaper by Al-Qaeda's followers, two million people in Paris, including President Hollande, and more than forty world leaders led a rally of national unity. One teacher in Clichy-sous-Bois, a suburb with many immigrants, reported that three quarters of the students had refused to observe the minute of silence in memory of the victims of the attack.[66] There have been about two hundred incidents in schools after the attack, some of them "glorifying terrorism".[66] In Bobigny, a suburb of Paris, a couple of students grunted Allahu Akbar during the minute of silence, the same words that were shouted by the terrorists during the attack.[67]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A French Islam is possible" (PDF). Institut Montaigne. 2016. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2017.

- ↑ Knox, Noelle (11 August 2005). "Religion takes a back seat in Western Europe". USA Today.

- ↑ "France – church attendance". France – church attendance. Via Integra. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Eurobarometer on Biotechnology" (PDF). Special Eurobarometer (341). European Commission. October 2010. p. 381.

- 1 2 "Catholicisme et protestantisme en France – Analyses sociologiques et données de l'Institut CSA pour La Croix" [Catholicism and Protestantism in France – Sociological analysis and data from the CSA Institute for La Croix] (PDF) (in French). CSA. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Barbier-Bouvet, Jean-François; Lafitte, Serge; Andries, Chloé; Sauvaget, Bernadette; Douillet, Cyril; Khoury, Yasmina (1 January 2007). "La France est-elle encore catholique? Sondage CSA". Le Monde des Religions (21). Data (archived).

- ↑ La-Croix.com (2018-03-23). "Dieu existe, pour la majorité des jeunes Français". La Croix (in French). Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- ↑ Bullivant, Stephen (2018). "Europe's Young Adults and Religion: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014-16) to inform the 2018 Synod of Bishops" (PDF). St Mary's University's Benedict XVI Centre for Religion and Society; Institut Catholique de Paris. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "European Social Survey, Online Analysis". nesstar.ess.nsd.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- ↑ Baubérot, Jean (15 March 2001). "The Secular Principle". Embassy of France in the US. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008.

- ↑ Ruth Whelan, and Carol Baxter, eds. Toleration and religious identity: the Edict of Nantes and its implications in France, Britain and Ireland (Four Courts PressLtd, 2003).

- ↑ Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2003). Western Civilization – Volume II: Since 1500 (5th ed.). p. 410.

- ↑ Philippe Joutard, "The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes: End or Renewal of French Protestantism?." in Menna Prestwich, ed., International Calvinism 1541-1715 (1985): 1541-1715.

- ↑ Gemma Betros, "The French Revolution and the Catholic Church" History Review (Dec 2010), Issue 68 pp 16-21.

- ↑ Charles A. Gliozzo, "The Philosophes and Religion: Intellectual Origins of the Dechristianization Movement in the French Revolution." Church History (1971). 40#3 275+. online

- 1 2 3 4 Popkin, Jeremy D (2015). A Short History of the French Revolution. Sixth ed. 2015

- ↑ Stanley J. Idzerda, "Iconoclasm during the French Revolution." American Historical Review (1954) 60#1: 13-26. online

- ↑ R.R. Palmer,. Twelve Who Ruled: The Year of the Terror in the French Revolution (1941) pp 220-22.

- ↑ Sanja Perovic, "The French Republican Calendar: Time, History and the Revolutionary Event." Journal for Eighteenth‐Century Studies 35.1 (2012): 1-16.

- ↑ Zerubavel, Eviatar. "The French Republican Calendar: a case study in the sociology of time." American Sociological Review (1977) 42#6: 868-877. online

- 1 2 3 Stevenson, Shandi (2013). "Religions of Revolution: The Merging of Religious and Political in the Cult of Reason and the Cult of the Supreme being in France 1793–1794." Order No. 1524274, California State University, Dominguez Hills, 2013. https://search-proquest-com.du.idm.oclc.org/docview/1461390217?accountid=14608.

- ↑ Gemma Betros, "The French Revolution and the Catholic Church." History Review 68 (2010): 16-21.

- ↑ Robert Tombs, France: 1814-1914 (1996) p 241

- ↑ Nigel Aston, Religion and revolution in France, 1780-1804 (Catholic University of America Press, 2000) pp 279-335.

- ↑ Frederick B. Artz, France under the Bourbon Restoration, 1814-1830 (1931) pp 99-171.

- ↑ James McMillan, "Catholic Christianity in France from the Restoration to the separation of church and state, 1815-1905." in Sheridan Gilley and Brian Stanley, eds., The Cambridge history of Christianity (2014) 8: 217-232

- ↑ Natalie Isser, "Protestants and Proselytization During the Second French Empire." Journal of Church and State 30.1 (1988): 51-70. online

- ↑ Roger L. Williams, Gaslight and Shadow the World of Napoleon III 1851 1870 (1957), pp 70-96, 194-95.

- ↑ Theodore Zeldin, France, 1848-1945: volume II: Intellect, Taste and Anxiety (1977) pp 986-1015.

- ↑ Rigoulot, Philippe (2009). "Protestants and the French nation under the Third Republic: Between recognition and assimilation". National Identities. 11 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1080/14608940802680961.

- ↑ Harrigan, Patrick J. (2001). "Church, State, and Education in France From the Falloux to the Ferry Laws: A Reassessment". Canadian Journal of History. 36 (1): 51–83.

- ↑ "Leo XIII – Nobilissima Gallorum Gens". vatican.va. (full text)

- ↑ "Leo XIII – Au milieu des sollicitudes". vatican.va. (full text)

- ↑ Tallett, Frank; Atkin, Nicholas (1991). Religion, society, and politics in France since 1789. London: Hambledon Press. p. 152. ISBN 1-85285-057-4.

- ↑ Porch, Douglas (2003). The March to the Marne: The French Army 1871–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–104. ISBN 0-521-54592-7. , is the most thorough account in English.

- ↑ Maurice Larkin, Church and state after the Dreyfus affair: The separation issue in France (1974).

- ↑ Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad and Michael J. Balz, "The October Riots in France: A Failed Immigration Policy or the Empire Strikes Back?" International Migration (2006) 44#2 pp 23–34.

- ↑ "Special Report: Riots in France". BBC News. 9 November 2005. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- ↑ Laurent Mucchielli, "Autumn 2005: A review of the most important riot in the history of French contemporary society." Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (2009) 35#5 pp. 731–751.

- 1 2 Cathy Lisa Schneider, "Police Power and Race Riots in Paris," Politics & Society (2008) 36#1 pp 133–159 on p. 136

- ↑ Steven Erlangerjan, "Days of Sirens, Fear and Blood: ‘France Is Turned Upside Down’", New York Times Jan 9, 2015

- 1 2 Gira, Dennis (2011–2012). "The "Inculturation" of Buddhism in France". Études. 415. S.E.R. pp. 641–652. ISSN 0014-1941.

- ↑ What place for Buddhism in secular France? (Video). AFPTV. 12 September 2016. See the section with a speech by Marion Dapsance.

- 1 2 3 "Religion, Ipsos Global Trends". Ipsos. 2017. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. About Ipsos Global Trends survey

- ↑ Anning, Caroline (22 June 2012). "Europe's largest Buddhist temple to open". BBC News.

- 1 2 3 "Sondage « Les protestants en France en 2017 » (1): qui sont les protestants?" [Survey "Protestants in France in 2017" (1): Who are the Protestants?]. Reforme.net (in French). 26 October 2017.

- 1 2 "France". Resources on Faith, Ethics and Public Life. Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. See drop-down essay on "Religion and Politics until the French Revolution"

- ↑ Cécile Chambraud (12 January 2017). "Une enquête inédite dresse le portrait des catholiques de France, loin des clichés" [An unprecedented survey portrays Catholics in France, far from clichés] (in French). Le Monde. Retrieved 15 September 2017. The researchers are Yann Raison du Cleuziou, senior lecturer in political science at the University of Bordeaux, and Philippe Cibois, professor emeritus of sociology. Their research was unpublished as of the time of the article.

- ↑ Fourquet, Jérôme (July 2012). "Enquête auprès des protestants" [Inquiry about the Protestants] (PDF) (in French). Institut français d'opinion publique.

- ↑ Jérôme Fourquet; Hervé Le Bras (2014). "La religion dévoilée" (PDF). Jean Jaurès Fondation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2017.

- ↑ "Assemblée des évêques orthodoxes de France".

- ↑ "French Coptic Orthodox Church".

- 1 2 "Fédération Chrétienne des Témoins de Jéhovah de France v. France". Reports of Judgments and Decisions 2001. XI. European Court of Human Rights.

- ↑ "France: How Many Jehovah's Witnesses Are There?". JW.ORG.

- ↑ "France". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ↑ "Le Bilan de la Shoah en France (Le régime de Vichy)" [The Report of the Holocaust in France (The Vichy regime)]. BS Encyclopédie.

- ↑ Croes, Marnix (2006). "The Holocaust in the Netherlands and the Rate of Jewish Survival" (PDF). Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 474–499. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcl022.

- 1 2 3 Ducré, Léa (26 March 2014). "Les deux visages du néopaganisme français" [The two faces of French Neopaganism] (in French). Le Monde des Religions.

- ↑ "Most Bahá'í Nations (2005)". The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005.

- ↑ "Les sectes en France: Nombre d'adeptes ou sympathisants" [Sects in France: Number of followers or sympathisers]. Quid (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2009.

- ↑ Dericquebourg, Régis (9–12 April 2003). De la MILS à la MIVILUDES: la politique envers les sectes en France après la chute du governement socialiste [From MILS to MIVILUDES: Politics towards sects in France after the fall of the socialist government]. CENSUR International Conference (in French). Vilnius (Lithuanie): CESNUR.

- 1 2 Tajuddin, Razia. "Islam in Paris". Euro-Islam: News and Analysis on Islam in Europe and North America. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011.

- ↑ Cole, Juan (1 July 2015). "Sharpening Contradictions: Why al-Qaeda attacked Satirists in Paris". Informed Comment.

- ↑ Porter, Tim (16 June 2015). "French Muslim leader Dalil Boubaker calls for empty Catholic churches to be turned into mosques". International Business Time.

- 1 2 Maussen, M. J. M. (2009). "Constructing mosques: The governance of Islam in France and the Netherlands". UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository), University of Amsterdam. pp. 155, 186, 172.

- 1 2 De la Baume, Maïa (22 January 2015). "Paris Announces Plan to Promote Secular Values". The New York Times. p. A4.

- ↑ "Teachers face difficult test in wake of Charlie Hebdo tragedy". France 24. 13 January 2015.

Further reading

- Aston, Nigel. (2000) Religion and Revolution in France, 1780–1804

- Bowen, John Richard. (2007) Why the French don't like headscarves: Islam, the state, and public space (Princeton UP)

- Curtis, Sarah A. (2000) Educating the Faithful: Religion, Schooling, and Society in Nineteenth-Century France (Northern Illinois UP)

- Edelstein, D. (2009). The Terror of Natural Right: Republicanism, the Cult of Nature, and the French Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Furet, F. (1981). Interpreting the French Revolution. Cambridge UP.

- Gibson, Ralph. (1989) A social history of French Catholicism, 1789-1914 Routledge, 1989.

- Hunt, L. (1984). Politics, culture, and class in the French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Israel, J. (2014). Revolutionary Ideas: An Intellectual History of the French Revolution from The Rights of Man to Robespierre. Princeton University Press.

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. (1969) Christianity in a Revolutionary Age: Volume I: The Nineteenth Century in Europe: Background and the Roman Catholic Phase online passim on Catholics in France.

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. (1959) Christianity in a Revolutionary Age: Vol II: The Nineteenth Century in Europe: The Protestant and Eastern Churches; pp 224–34 on Protestants in France.

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. (1959) Christianity in a Revolutionary Age: Vol IV: The Twentieth Century in Europe: The Roman Catholic, Protestant, and Eastern Churches pp 128–53 on Catholics in France; pp 375–79 on Protestants.

- McMillan, James. (2014) "Catholic Christianity in France from the Restoration to the separation of church and state, 1815-1905." in Sheridan Gilley and Brian Stanley, eds., The Cambridge history of Christianity (2014) 8: 217-232

- Misner, Paul. (1992) "Social catholicism in nineteenth-century Europe: A review of recent historiography." Catholic Historical Review 78.4 (1992): 581-600.

- Price, Roger, Religious Renewal in France, 1789-1870: The Roman Catholic Church between Catastrophe and Triumph (2018) online review

- Tallett, Frank, and Nicholas Atkin. Religion, society, and politics in France since 1789 (1991)

- Willaime, Jean-Paul. (2004) "The cultural turn in the sociology of religion in France." Sociology of Religion 65.4 (2004): 373-389.

- Zeldin, Theodore. (1977) France, 1848-1945: Intellect, taste, and anxiety. Vol. 2. (Oxford UP) pp 983–1039.