Religion in Iceland

Formal religious affiliation in Iceland (2018)[1]

Religion in Iceland has been predominantly Christian since its adoption as the state religion by the Althing under the influence of Olaf Tryggvason, the king of Norway, in 999/1000 CE. Before that, between the 9th and 10th century, the prevailing religion among the early Icelanders (mostly Norwegian settlers fleeing Harald Fairhair's monarchical centralisation in 872–930) was the northern Germanic religion, which persisted for centuries even after the official Christianisation of the state.

Starting in the 1530s, Iceland, originally Catholic and under the Danish crown, formally switched to Lutheranism with the Icelandic Reformation, which culminated in 1550.[2] The Lutheran Church of Iceland has remained since then the country's state church.[2] Freedom of religion has been granted to the Icelanders since 1874. The Church of Iceland is supported by the government, but all registered religions receive support from a church tax (sóknargjald) paid by taxpayers over the age of sixteen.[3]

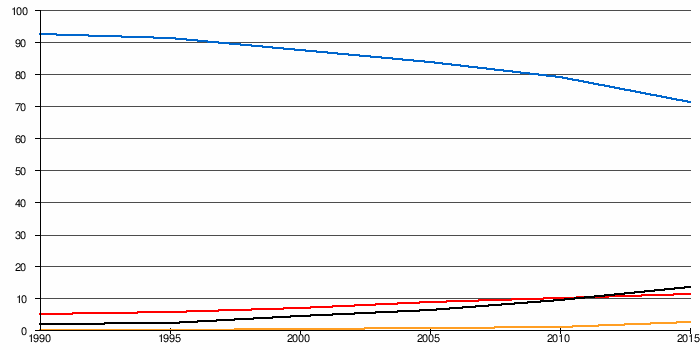

Since the late 20th century, and especially the early 21st century, religious life in Iceland has become more diverse, with a decline of Christianity, the rise of unaffiliated people, and the emergence of new religions, notably Heathenry, in Iceland also called Ásatrú, which seeks to reconstruct the Germanic folk religion. A large part of the population remain members of the Church of Iceland, but are actually irreligious and atheists, as demonstrated by demoscopic analyses.[4]

Demographics

Major religious groups by year

Table

| Religion | 1990[5] | % | 1995[5] | % | 2000[5] | % | 2005[5] | % | 2010[5] | % | 2015[5] | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church of Iceland[lower-alpha 1] | 236.959 | 92.6% | 245.049 | 91.5% | 248.411 | 87.8% | 251.728 | 84.0% | 251.487 | 79.1% | 237.938 | 71.5% |

| Other Protestants and Christians | 11.146 | 4.3% | 12.709 | 4.7% | 15.924 | 5.6% | 19.684 | 6.6% | 22.987 | 7.2% | 26.297 | 7.9% |

| Catholic Church | 2.396 | 0.9% | 2.553 | 0.95% | 4.307 | 1.5% | 6.451 | 2.15% | 9.672 | 3.0% | 12.414 | 3.7% |

| Heathenism | 98 | 0.03% | 190 | 0.07% | 512 | 0.2% | 953 | 0.3% | 1.422 | 0.4% | 3.210 | 1.0% |

| Zuism | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3.087 | 1.0% |

| Buddhism | - | - | 230 | 0.08% | 466 | 0.2% | 685 | 0.2% | 1.090 | 0.3% | 1.336 | 0.4% |

| Islam | - | - | - | - | 164 | 0.05% | 341 | 0.1% | 591 | 0.2% | 865 | 0.3% |

| Humanism | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.456 | 0.4% |

| Bahá'í Faith | 378 | 0.1% | 402 | 0.15% | 386 | 0.1% | 389 | 0.1% | 398 | 0.1% | 365 | 0.1% |

| Other and unspecified[lower-alpha 2] | 1.505 | 0.6% | 2.753 | 1.0% | 6.325 | 2.2% | 11.794 | 3.9% | 19.647 | 6.2% | 26.359 | 7.9% |

| Unaffiliated[lower-alpha 3] | 3.373 | 1.3% | 3.923 | 1.4% | 6.350 | 2.2% | 7.379 | 2.5% | 10.336 | 3.2% | 19.202 | 5.7% |

| Population | 255.855 | 100% | 267.809 | 100% | 282.845 | 100% | 299.404 | 100% | 317.630 | 100% | 332.529 | 100% |

Line chart

Religious organisations' membership in the current year

| Organisation | Religion | Members | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Church of Iceland[lower-alpha 1] (Þjóðkirkjan) |

Christianity | 236,481 | 69.89 |

| Other and unspecified[lower-alpha 2] | Various | 31,021 | 9.17 |

| Unaffiliated[lower-alpha 3] | Unknown | 20,500 | 6.06 |

| Catholic Church (Kaþólska kirkjan) |

Christianity | 12,901 | 3.81 |

| Reykjavík Free Church (Fríkirkjan í Reykjavík) |

Christianity | 9,648 | 2.85 |

| Hafnarfjörður Free Church (Fríkirkjan í Hafnarfirði) |

Christianity | 6,631 | 1.96 |

| Ásatrú Fellowship (Ásatrúarfélagið) |

Heathenism, Paganism | 3,583 | 1.06 |

| Independent Congregation (Óháði söfnuðurinn) |

Christianity | 3,281 | 0.97 |

| Zuism (Zúismi) |

Sumerian religion, Paganism | 2,845 | 0.84 |

| Pentecostal Church of Iceland (Hvítasunnukirkjan á Íslandi) |

Christianity | 2,080 | 0.61 |

| Icelandic Ethical Humanist Association (Siðmennt, félag siðrænna húmanista á Íslandi) |

Humanism | 1,789 | 0.53 |

| Buddhist Association of Iceland (Búddistafélag Íslands) |

Buddhism | 1,048 | 0.31 |

| Seventh-day Adventist Church in Iceland (Kirkja sjöunda dags aðventista á Íslandi) |

Christianity | 698 | 0.21 |

| Jehovah's Witnesses (Vottar Jehóva) |

Christianity | 642 | 0.19 |

| Russian Orthodox Church in Iceland (Rússneska rétttrúnaðarkirkjan) |

Christianity | 622 | 0.18 |

| Muslim Association of Iceland (Félag múslima á Íslandi) |

Islam | 542 | 0.16 |

| The Way (Vegurinn) |

Christianity | 541 | 0.16 |

| Smárakirkja | Christianity | 511 | 0.15 |

| Islamic Cultural Center of Iceland (Menningarsetur múslima á Íslandi) |

Islam | 406 | 0.12 |

| Bahá'í Faith in Iceland (Bahá'í samfélagið á Íslandi) |

Bahá'í Faith | 363 | 0.11 |

| Serbian Orthodox Church in Iceland (Serbneska rétttrúnaðarkirkjan) |

Christianity | 339 | 0.10 |

| Icelandic Christ-Church (Íslenska Kristskirkjan) |

Christianity | 253 | 0.07 |

| Catch the Fire Reykjavík (Catch the Fire (CTF)) |

Christianity | 180 | 0.05 |

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Kirkja Jesú Krists hinna síðari daga heilögu) |

Christianity | 169 | 0.05 |

| SGI in Iceland (SGI á Íslandi) |

Buddhism | 168 | 0.05 |

| Zen in Iceland – Night Pasture (Zen á Íslandi - Nátthagi) |

Buddhism | 135 | 0.04 |

| Free Church Kefas (Fríkirkjan Kefas) |

Christianity | 135 | 0.04 |

| Betania (Betanía) |

Christianity | 133 | 0.04 |

| Church of Evangelism (Boðunarkirkjan) |

Christianity | 120 | 0.04 |

| Homechurch (Heimakirkja) |

Christianity | 90 | 0.03 |

| The Salvation Army (Hjálpræðisherinn) |

Christianity | 59 | 0.02 |

| Sjónarhæð Congregation (Sjónarhæðarsöfnuðurinn) |

Christianity | 55 | 0.02 |

| Church of God Ministry of Jesus Christ International (Alþjóðleg kirkja Guðs og embætti Jesú Krists) |

Christianity | 51 | 0.02 |

| House of Prayer (Bænahúsið) |

Christianity | 37 | 0.01 |

| Heaven on Earth (Himinn á jörðu) |

Christianity | 35 | 0.01 |

| Church of the Resurrected Life (Kirkja hins upprisna lífs) |

Christianity | 27 | 0.01 |

| Believers' Fellowship (Samfélag trúaðra) |

Christianity | 28 | 0.01 |

| Beth-Shekhinah Apostolic Church (Postulakirkjan Beth-Shekhinah) |

Christianity | 28 | 0.01 |

| Reykjavik Priesthood (Reykjavíkurgoðorð) |

Heathenism, Paganism | 26 | 0.01 |

| First Baptist Church (Fyrsta baptistakirkjan) |

Christianity | 24 | 0.01 |

| DíaMat | Dialectical materialism | 23 | 0.01 |

| Emmanuel Baptist Church (Emmanúel baptistakirkjan) |

Christianity | 23 | 0.01 |

| Redeemed Christian Church (Endurfædd kristin kirkja) |

Christianity | 21 | 0.00 |

| Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (Fjölskyldusamtök heimsfriðar og sameiningar) |

Christianity | 20 | 0.01 |

| Port of Hope (Vonarhöfn) |

Christianity | 19 | 0.01 |

| Iceland Christian Nation (Ísland kristin Þjóð) |

Christianity | 14 | 0.00 |

| New Avalon (Nýja Avalon) |

Theosophy | 4 | 0.00 |

| Population | 338,349 | 100.00 |

History

9th–10th century: Early Germanic settlement

When Iceland was first settled by Norwegians (but also by some Swedes and people from the Norse settlements in Britain[6]) in the mid-9th century, approximately in 870,[7] it was inhabited by a small number of Irish Christian anchorites known as papar (singular papi). When Scandinavians began to arrive in larger numbers, the anchorites left of their own or were driven out.[8] The migration of Norwegians was partly in response to the politics of Harald Fairhair, who was unifying Norway under a centralised monarchy.[7]

The first Icelanders, though accustomed to a society in which the monarch was essential for religious life, did not establish a new monarchy in the colony, but rather a yearly assembly of free men, the Althing. The "things" were assemblies of free men who governed Germanic societies, and they were led by a holy kingship. The Icelandic thing developed peculiar characteristics; in place of the loyalty to a holy king, the Icelanders established the loyalty to a law code, first composed by Úlfljót who studied Norwegian laws.[7]

Icelandic landowners (landnámsmenn[8]) were organised into goðorð ("god-word(s)"), religio-political groups under the leadership of a goði ("god-man"). The goðar were part-time priests who officiated ritual sacrifices at the local temple and had some qualities of the Germanic kings; they organised local things and represented them at the Althing. Úlfljót was chosen as the first Lawspeaker (Lögsögumaðr), who presided the Althing which met annually at Thingvellir. The religio-political organisation of early Iceland has been defined as "pagan and anti-monarchic", which distinguished it from other Germanic societies. Concerning other religious practices, the Icelanders followed Scandinavian norms; they built temples enshrining images of the gods.[7]

The religion was named Goðatrú or Ásatrú, "truth of the gods". Icelanders worshipped landvættir, local land spirits, and the gods of the common northern Germanic tradition, within hof and hörgar. The most popular deity was apparently Thor, whom the Icelanders worshipped in the form of high pillars; poets worshipped Odin, as highlighted by Hallfreðr Vandræðaskáld, the Landnámabók and the Eyrbyggja saga. Other people worshipped Freyr, as attested in the Víga-Glúms saga.[9]

10th–11th century: Christianisation

_%C3%BE%C3%ADngmannakirkja.jpg)

Apart from the Irish papar, Christianity had been present in Iceland from the start even among the Germanic settlers. The Landnámabók gives the names of Christian settlers, including an influential woman named Aud the Deep-Minded. Icelanders generally tended to syncretism, integrating Jesus Christ among their deities rather than converting to the Christian doctrine. For instance, Aud the Deep-Minded was among the baptised and devout Christians and she established a Christian cross on a hill, where she prayed; her kinsmen later regarded the site as sacred, and they built an Ásatrú temple there.[9] These first Christians were probably influenced by contact with Norse people in Britain, where Christianity already had a strong presence.[10] Among the first settlers, the vast majority were worshippers of the Germanic gods, and organised Christianity probably died out in one or two generations.[10] The syncretic attitude of the Icelanders made possible for the Germanic religion to survive and intermingle with Christianity even in later periods. It is recorded in the Eyrbyggja saga that as Norway was being Christianised, a pagan temple was dismantled there to be reassembled in Iceland.[11]

The adoption of Christianity—which then was still identical to the Catholic Church—as the state religion (kristnitaka, literally the "taking of Christianity"[12]), and therefore the formal conversion of the entire population, was decided by the Althing in 999/1000,[9] pushed by the king of Norway, Olaf Tryggvason.[13] In that year, Christianity was still a minority in Iceland, while the belief in the Germanic religion was strong. However, some Christians had acquired high positions in the goðorð system and therefore considerable power in the Althing.[9]

Christian missionaries began to be active in Iceland by 980. One of them was the Icelandic native Thorvald Konradsson, who had been baptised on the continent by the Saxon bishop Fridrek, with whom he preached the gospel in Iceland in 981, converting only Thorvald's father Konrad and his family. They were unsuccessful and even had a clash with pagans at the Althing, killing two men. After the event, in 986 Fridrek returned to Saxony while Thorvald embarked for Viking expeditions in Eastern Europe. Among the other proselytisers, King Olaf of Norway sent the Icelandic native Stefnir Thorgilsson in 995–996 and the Saxon priest Thangbrand in 997–999. Both the missions were unsuccessful: Stefnir violently destroyed temples and ancestral shrines, leading the Althing to enact a law against Christians—who were declared frændaskomm, a "disgrace on one's kin", and could now be denounced—and to outlaw Stefnir, who returned to Norway; Thangbrand, a learnt but violent man, succeeded in converting some important families, but he also had many opponents, and, when he killed a poet—who had composed verses against him—, he was outlawed and he too went back to Norway.[6]

At this point, Olaf Tryggvason suspended Iceland's trade with Norway (a concrete threat for Icelandic economy) and threatened to kill Icelanders residing in Norway (who were for the most part sons and relatives of prominent goðar) as long as Iceland remained a pagan country. Iceland sent a delegation, belonging to the Christian faction, to obtain the release of the hostages and promise the conversion of the country to Christianity. Meanwhile, in Iceland the situation was worsening, as the two religious factions had divided the country and a civil war was about to break out. However, the mediation of the Althing, presided by the lawspeaker Thorgeir Thorkelsson, thwarted the conflict.[6] Thorgeir was trusted by both the religious factions, and he was given the responsibility to decide whether Icelanders would have converted to Christianity or would have remained faithful to the Germanic religion of their ancestors. After one day and one night, he decided that, in order to keep peace, the population had to be united under one law and one religion, Christianity, and all the non-Christians among the population would have received baptism. At first, it was maintained the right for people to sacrifice to the old gods in private, though it was punishable if witnesses were provided. A few years later, these provisions allowing private cults were abolished.[14]

The decision of the Althing was a turning point; before that, it was difficult for individuals to convert to Christianity, since it would have meant to abandon the traditions of one's own kin, and would have been seen as ættarspillar—"destruction of kinship".[15] Despite the official Christianisation, the old Germanic religion persisted for long time, as proven by the literature produced by Snorri Sturluson—himself a Christian—and other authors in the 13th century, who composed the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda.[16] After the conversion, members of the goðorð often became Christian priests and bishops. The first consecrated bishop in Iceland was Ísleif Gizursson, who from 1057 to his death in 1080 was the bishop of Skálholt. He is credited with having instituted a tithe system which made the Icelandic church financially independent and strengthened Christianity.[15]

16th century: Protestant Reformation

_Kirchliche_Einteilung_(Bist%C3%BCmer)_Islands_im_Mittelalter.jpg)

The last two Catholic bishops of Iceland were the Øgmundur Pállson of Skálholt and Jón Arason of Hólar. Jón was a poet of some importance and was married with many children, a usual thing among the clergy in Iceland. The two bishops, who were not well versed in theology but were men of great power, were in conflict with one another and threatened open conflict. At the Althing of 1526 they came with their own armed contingents, though they reconciled because of the threat posed by a new, common enemy, the spread of Lutheranism.[17]

Lutheran pamphlets were introduced in Iceland through the trade communication with Germany. In 1533, the Althing ordained that "all shall continue in the Holy Faith and the Law of God, which God has given to us, and which the Holy Fathers have confirmed". Among the first Lutherans there was Oddur Gottskálksson, who had converted to Lutheranism while living on the continent for many years. When he went back to Iceland, he became the secretary of the bishop of Skálholt and translated the New Testament in the Icelandic language.[18]

The most important figure in early Icelandic Lutheranism was, however, Gissur Einarsson, who during a period of study in Germany became knowledgeable about the Reformation. In 1536, he became assistant at the Skálholt bishopric, though he still did not formally embrace Lutheranism. When Lutheranism became the state religion of Denmark and Norway under the king Christian III, this last tried to convert Iceland too. In 1538, the "Church Ordinance" (the royal invitation to convert) was put before the two bishops Øgmundur and Jón at the Althing, but it was rejected. Then, Christian III ordered the dissolution of the monasteries. Bishop Øgmundur, now old and almost blind, chose Gissur Einarsson as his successor. He was examined by theologians in Copenhagen and in 1540 the king appointed him as the superintendent of Skálholt. Gissur was only twenty-five years old and it was difficult for him to maintain power, especially as he was opposed by the clergy and even by the old bishop. A royal emissary was sent to clinch the ordinance, and Øgmundur was arrested and died during the travel to Denmark. The ordinance was accepted in Skálholt, but rejected by Jón Arason in Hólar. Bishop Gissur, who was ordained by the Danish bishop Peder Palladius, reorganised the church in his diocese according to Lutheran principles, including the suppression of Catholic ceremonies and the exhortation of clergy marriage. He intrusted Oddur Gottskálksson with the translation of German sermons, and he himself translated parts of the Old Testament and the Church Ordinance.[18]

Gissur Einarsson died in 1548 and Jón Arason took possession of the Skálholt diocese, despite the clergy opposed him. He also imprisoned Gissur's appointed successor. Jón Arason was consequently outlawed by the king, he was arrested with two of his sons, and all three were executed in November 1550.[18] In 1552 also the Hólar diocese accepted the Church Ordinance. Institutional opposition to the Reformation had now vanished, so that church properties were secularised and churches and monasteries were plundered. However, it took many decades for Lutheranism to be firmly established in Iceland. Church manuals and hymnals were in bad Danish translations, and new schools had to be set up in cathedral towns to train the Lutheran clergy. Bishop Palladius took care of the development of the Icelandic Lutheran church in those early years. The able and energetic Gudbrandur Thorláksson, bishop of Hólar from 1571 to 1627, devoted his energies in improving church literature, clergy training and community education. In 1584 the first Icelandic translation of the Bible was published.[19]

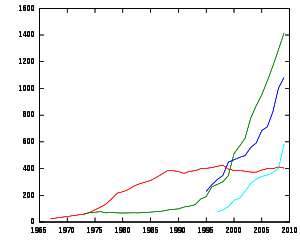

20th–21st century: Decline of Christianity and rise of new religions

.svg.png)

Since the end of the 19th century, Iceland has been more open to new religious ideas than many other European countries.[20] In the 19th and early 20th century, religious life in Iceland, still mostly within the Christian establishment, was influenced by the spread of spiritualist beliefs.[21] Theosophy was introduced in Iceland around 1900, and in 1920 the Icelandic Theosophists formally organised as an independent branch of the international Theosophical movement, though within the fold of the Lutheran belief and led by a Lutheran pastor, Séra Jakob Kristinsson.[22]

Since the late 20th century there has been a swift diversification of the religious life in the country. The most notable phenomenon has been a rise of Neopagan religions, especially Heathenry, in Iceland also called Ásatrú, "truth of the gods", the return to Germanic religion. This may have been powered by the fact that the Icelandic language has a literary tradition that predates the island's conversion to Christianity, the Eddas and the Sagas, which are well known by most Icelanders, providing an unbroken link with the pagan past.[20]

In 1972, four men proposed to found an organisation for the revitalisation of pre-Christian northern Germanic religion. They founded the Ásatrúarfélagið and asked the Ministry of Justice and Ecclesiastical Affairs whether it could be possible for the new organisation to be recognised, giving its chief priest the same legal status as a Christian pastor. In the autumn of the same year, they asked to be registered, and by the spring of 1973 Ásatrú had become a recognised religion.[20]

In the early 2010s, Zuism, a reinstitution of the Sumerian religion, was founded in Iceland and formally registered in 2013. In late 2015, the Board of Directors of the Zuist Church was hijacked by people who were unrelated to the movement, and under the new leadership Zuism was turned into a medium for a protest against the state church and the Icelandic church tax (sóknargjald). Zuism, unlike other religions, promised to share among its adherents the money it receives from the tax, so that in a few weeks thousands of people joined the church. After a legal struggle, the original directors were reinstated as the leaders of the movement, and by October 2017, after two years of frozen activity, the case was closed allowing the church to dispose of its taxes.[23] This church has kept the principle of funds' redistribution among members, which is called amargi.[24]

Religions and life stances

As of 2017, 84.77% of the Icelanders were affiliated with some religion officially recognised by the government and listed in the civil registry, 9.17% were members of some unspecified other religions not registered within the civil registry, and 6.06% were unaffiliated with any religion.[1]

Christianity

As of 2017, 81.53% of the Icelandic people were registered as Christians, most of them belonging to the Church of Iceland and minor Lutheran free churches.[1] Catholics were 3.81%, and a further 2.08% of the Icelanders were adherents of some other Christian denomination.[1]

Lutheranism

In 2017, 69.89% of the Icelanders were registered as members of the national Church of Iceland. In addition, in the country there are a number of Lutheran free churches, including the Reykjavík Free Church (2.85%), the Hafnarfjörður Free Church (1.96%) and the Independent Lutheran Congregation (0.97%).[1]

Catholicism

As of 2017, the Catholic Church is the largest non-Lutheran form of Christianity in Iceland, accounting for 3.81% of the population, many of whom are immigrant Poles.[1] Catholics are organised in the Diocese of Reykjavík, led by the bishop Dávid Bartimej Tencer (1963–), O.F.M. Cap..[25]

In the twentieth century, Iceland had some notable converts to Catholicism, including Halldór Laxness and Jón Sveinsson. The latter moved to France at the age of thirteen and became a Jesuit, remaining in Society of Jesus for the rest of his life. He was a valued author of books for children, written in German, and even appeared on postage stamps.[26]

Pentecostalism

As of 2017, 0.61% of the Icelanders were registered as members of the Pentecostal Church of Iceland.[1]

Seventh-day Adventism

As of 2017, 0.21% of the Icelanders were registered as members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.[1]

Mormonism

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has 169 registered members in Iceland as of 2017.[1] The church itself claims a higher number of 277 members in two branches (Reykjavík and Selfoss).[27] A family history center for the church is located in the Mormon meetinghouse of Reykjavík.[28]

Baptists

There are very few Baptists in Iceland, members of churches such as the First Baptist Church (23 members in 2017[1]) and the Upstairs Room (Loftstofan) Baptist Church.[29]

Orthodox Christianity

Eastern Orthodox Christianity has a presence in Iceland with the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Russian Orthodox Church. As of 2017 they had 339 members (0.1% of the population) and 622 members (0.18%), respectively.[1]

Jehovah's Witnesses

The Jehovah's Witnesses in Iceland were 642, or 0.19% of the population, as of 2017.[1]

A Russian Orthodox church in Reykjavík.

A Russian Orthodox church in Reykjavík.- Lutheran cathedral of Reykjavík.

- Catholic church of Akureyri.

.jpg) Reykjavík Free Church building in the foreground, and the Hallgrímskirkja in the background.

Reykjavík Free Church building in the foreground, and the Hallgrímskirkja in the background. Theosophical Society in Reykjavík.

Theosophical Society in Reykjavík.- Interior of the Lutheran cathedral of Skálholt

.jpg) Wooden church in the Westfjords.

Wooden church in the Westfjords. Stone church in Hvalsnes, Reykjanes.

Stone church in Hvalsnes, Reykjanes. Turf church in Víðimýri.

Turf church in Víðimýri. Modern church in Kirkjubæjarklaustur.

Modern church in Kirkjubæjarklaustur.

Non-Christian religions

Heathenry

From the 1970s there has been a rebirth of the northern Germanic religion in Iceland.[20] As of 2017, about 1.2% of the Icelanders registered as members of the Ásatrúarfélagið (literally "Ese-truth Fellowship").[1] The Reykjavíkurgoðorð ("Reykjavík God-word") is another independent Heathen group and it had 26 members in 2017.[1]

Zuism

Zuism in 2017 was the religion of about 0.6% of the Icelandic population.[1] It is a reinstitution of the Sumerian religion, and Zuists worship An (the supreme God of Heaven), Ki (the Earth), as well as Enlil and Enki, Nanna (the Moon) and Utu (the Sun), Inanna (Venus), Marduk (Jupiter), Nabu (Mercury), Nergal (Mars), Ninurta (Saturn), and Dumuzi.[30]

Buddhism

The largest Buddhist organisation in Iceland, the Buddhist Association of Iceland, had 1048 members in 2017, or 0.3% of the population. Other Buddhist organisations present in Iceland are the Soka Gakkai International (with 168 members), Zen in Iceland—Night Pasture (with 135 members), and the Tibetan Buddhist Association. Collectively they accounted for 0.4% of the Icelanders as of 2017.[1]

Islam

Islam is the religion of a small minority in Iceland. The two largest organisations of Muslims are the Muslim Association of Iceland and the Islamic Cultural Centre of Iceland, with 542 and 406 members, respectively, in 2017. Together they comprised about 0.3% of the population of Iceland.[1] However, the total number of Muslims living in Iceland may be larger, as many Muslims have chosen to join neither association.[31]

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith in Iceland was the religion of 0.1% of the population in 2017.[1] It was introduced by the American Amelia Collins in 1924; the first Icelander who converted was called Hólmfríður Árnadóttir. The religion was recognised by the government in 1966, and the first Bahá'í National Spiritual Assembly was elected in 1972. The number of Bahá'í assemblies in Iceland is the highest, compared to the total population of the country, in all of Europe. The Danish scholar of religion Margit Warburg speculates that the Icelandic people are culturally more open to religious innovation.[32]

Judaism

The Jewish population in Iceland is not large enough to be registered as a separate religious group. There are no synagogues or prayer houses in the country. There was no significant Jewish population or emigration to Iceland until the 20th century, though some Jewish merchants lived in Iceland temporarily during the 19th century. The Icelanders' attitude towards the Jews has mostly been neutral, although in the early 20th century the intellectual Steinn Emilsson was influenced by anti-Semitic ideas while studying in Germany. Although most Icelanders deplored the persecutions of Jews during the Second World War, they usually refused entry to Jews who were fleeing Nazi Germany, so the Jewish population did not rise much during the war.[33]

The former First Lady of Iceland, Dorrit Moussaieff, is a Bukharian Jew and is likely the most significant Jewish woman in Icelandic history.

Hinduism

The number of Hindus in Iceland is unknown, since no religious movement of Hinduism is registered in the country. There are, however, a Sri Chinmoy centre, Ananda Marga, and other organisations of meditation and philosophy.[34]

Irreligion and humanism

Siðmennt (short name of the Icelandic Ethical Humanist Association) is the largest organisation promoting humanism in Iceland. It is similar to the Norwegian Humanist Association, and like it is recognised as a life stance community by the state since 2013, and therefore can receive funds from the state. As of 2017, it had 1789 registered members, or 0.6% of all the Icelanders).[1] Another 6.06% of the population were registered as having no religious affiliation in 2017.[1]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Currently, the state church of Iceland is the Evangelical Lutheran Church (Evangelíska lúterska kirkja), a Christian denomination, also known simply as the Church of Iceland or the National Church (Þjóðkirkjan).[1]

- 1 2 The category "other and unspecified" comprises citizens who are registered as members of religious organisations which are not listed in the civil registry.[1]

- 1 2 The category of the "unaffiliated" comprises citizens who are not registered as members of any religious organisation.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 "Populations by religious and life stance organizations". Statistics Iceland.

- 1 2 Lacy 2000, p. 166: "The Old Treaty, signed in 1262, that led to Iceland's being first under the Norwegian and later the Danish kings was such a milestone, as was the Reformation in 1550 whereby Lutheranism became, and remains, Iceland's state religion".

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of Iceland (No. 33, 17 June 1944, as amended 30 May 1984, 31 May 1991, 28 June 1995 and 24 June 1999)". Government of Iceland.

Section VI deals with religion.

Article 62: The Evangelical Lutheran Church shall be the State Church in Iceland and, as such, it shall be supported and protected by the State. This may be amended by law. Article 63: All persons have the right to form religious associations and to practice their religion in conformity with their individual convictions. Nothing may however be preached or practised which is prejudicial to good morals or public order. Article 64: No one may lose any of his civil or national rights on account of his religion, nor may anyone refuse to perform any generally applicable civil duty on religious grounds. Everyone shall be free to remain outside religious associations. No one shall be obliged to pay any personal dues to any religious association of which he is not a member. A person who is not a member of any religious association shall pay to the University of Iceland the dues that he would have had to pay to such an association, if he had been a member. This may be amended by law.

- ↑ "Global Index of Religion and Atheism" (PDF). WIN/GIA. 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rósant, Sigurður (29 March 2016). "Fjöldi meðlima í trúfélögum og öðrum samanburðarhópum 1990 - 2016". Trúrýni - trúarbrögðin sneiðmynduð. Sigurður Rósant's analysis of the official data published by Statistics Iceland.

- 1 2 3 D'Angelo 2016, p. 482.

- 1 2 3 4 Cusack 1998, p. 160.

- 1 2 Byock 1988, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 Cusack 1998, p. 161.

- 1 2 Byock 1988, p. 138.

- ↑ Cusack 1998, p. 168.

- ↑ D'Angelo 2016, p. 481.

- ↑ Jochens, Jenny (1999). "Late and Peaceful: Iceland's Conversion Through Arbitration in 1000". Speculum (74). pp. 621–655. doi:10.2307/2886763. JSTOR 2886763.

- ↑ D'Angelo 2016, p. 483.

- 1 2 Cusack 1998, p. 167.

- ↑ Cusack 1998, pp. 162, 168.

- ↑ Elton 1990, p. 154.

- 1 2 3 Elton 1990, p. 155.

- ↑ Elton 1990, p. 156.

- 1 2 3 4 Christiano, Swatos & Kivisto 2002, p. 331.

- ↑ Swatos, William H.; Gissurarson, Loftur Reimar (1997). Icelandic Spiritualism: Mediumship and Modernity in Iceland. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1412825776. passim.

- ↑ Fell 1999, p. 250.

- ↑ "Yfirlýsing frá Ágústi Arnari Ágústsssyni, forstöðumanni trúfélagsins Zuism". Zúistar á Íslandi. 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017.

- ↑ "Amargi (Endurgreiðsla Sóknargjalda)". Zúistar á Íslandi. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017.

- ↑ Chenery, David M. "Diocese of Reykjavik, Dioecesis Reykiavikensis". Catholic Hierarchy.

- ↑ "Jon Sveinsson, SJ (Nonni)". Manresa, Jesuit Retreat House.

- ↑ "Facts and Statistics: Iceland". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

- ↑ "Iceland". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

- ↑ Official website: Loftstofan Baptistakirkja.

- ↑ "Kennisetningar Zuism". Zuism Iceland. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018.

- ↑ Arnarsdóttir, Eygló Svala (2014). "To a Mosque on a Magic Carpet". Iceland Review. 52 (1). pp. 64–68.

- ↑ Hassall, Graham; Fazel, Seena (1998). "100 Years of the Bahá'í Faith in Europe". Bahá’í Studies Review (8). pp. 35–44.

- ↑ Bergsson, Snorri G. "Iceland and the Jewish Question until 1940". Archived from the original on 22 January 2008.

- ↑ "Hvað er hindúismi?". Áttavitinn. 29 July 2013.

Sources

- Byock, Jesse L. (1988). Medieval Iceland: Society, Sagas, and Power. University of California Press. ISBN 0520054202.

- Christiano, Kevin J.; Swatos, William H.; Kivisto, Peter (2002). Sociology of Religion: Contemporary Developments. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 0759100357.

- Cusack, Carole M. (1998). Conversion Among the Germanic Peoples. A&C Black. ISBN 0304701556.

- D'Angelo, Francesco (2016). "Althing of 1000 and the Conversion of Iceland to Christianity". In Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew. Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 481–483. ISBN 1610695666.

- Fell, Michael (1999). And Some Fell Into Good Soil: A History of Christianity in Iceland. American University Studies: Theology and Religion. 201. P. Lang. ISBN 0820438812.

- Elton, Geoffrey Rudolph (1990). The Reformation, 1520-1559. The New Cambridge Modern History. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521345367.

- Lacy, Terry G. (2000). Ring of Seasons: Iceland, Its Culture and History. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472086618.