Religion in Switzerland

Religion in Switzerland (population age 15+, 2016)[1]

Christianity is the predominant religion of Switzerland, its presence going back to the Roman era. Since the 16th century, Switzerland has been traditionally divided into Roman Catholic and Reformed confessions. However, adherence to Christian churches has declined considerably since the late 20th century, from close to 94% in 1980 to about 67% as of 2016. Furthermore notable is the significant difference in church adherence between Swiss citizens (72%) and foreign nationals (51%) in 2016.[1]

Switzerland as a federal state has no state religion, though most of the cantons (except for Geneva and Neuchâtel) recognize official churches (Landeskirchen), in all cases including the Roman Catholic Church and the Swiss Reformed Church. These churches, and in some cantons also the Old Catholic Church and Jewish congregations, are financed by official taxation of adherents.[2]

The Federal Statistical Office reported the religious demographics as of 2016 as follows (based on the resident population age 15 years and older): 66.9% Christian (including 36.5% Roman Catholic, 24.5% Reformed, 5.9% other), 24.9% unaffiliated, 5.2% Muslim, 0.3% Jewish, 1.4% other religions. (100%: 6,981,381, registered resident population age 15 years and older).[1]

Demographics

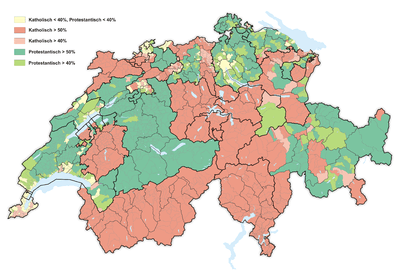

Until the 1970s, Protestants made up a majority of the Swiss population, decreasing to about a fourth nowadays. Some traditionally Protestant cantons and cities have today more Catholics than Protestants, due to a steady rise of the unaffiliated population in general combined with Catholic immigration from countries such as Italy, Spain, and Portugal, who mostly immigrated during the second half of the 20th century, and a less important immigration from Croatia during the last 25 years. 31% of all Catholics are foreign nationals versus 5% of Protestants. The unaffiliated form 25% of Switzerland's population in 2016,[1] and are especially strong in the canton of Basel-City, the canton of Neuchâtel, the canton of Geneva, the canton of Vaud, and Zürich. The country was historically about evenly balanced between Catholics and Protestants, with a complex patchwork of majorities over most of the country. One canton, Appenzell, was officially divided into Catholic and Protestant sections in 1597. The larger cities and their cantons (Bern, Geneva, Lausanne, Zürich and Basel) used to be predominantly Protestant. Central Switzerland, Valais, Ticino, Appenzell Innerrhodes, Jura, Fribourg, Solothurn, Basel-Country, St Gallen and the half of Aargau are traditionally Catholic. The Swiss Constitution of 1848, which came after the clashes between Catholic and Protestant cantons that culminated in the Sonderbundskrieg, consciously defines a consociational state, allowing the peaceful co-existence of Catholics and Protestants. A 1980 initiative calling for the complete separation of church and state was rejected by 78.9% of the voters.[3]

Rather recent immigration over the last 25 years has brought Islam (accounting for 5.2% in 2016[1]) and Eastern Orthodoxy as sizeable minority religions.[4]

Other Christian minority communities include Neo-Pietism, Pentecostalism (mostly incorporated in the Schweizer Pfingstmission), Methodism, the New Apostolic Church, Jehovah's Witnesses, and the Christian Catholic Church of Switzerland.[4] Minor non-Christian minority groups are Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism and other religions.[4]

A survey conducted by Pew Research Center in 2017 found that 75% of Swiss adult population consider themselves Christians when asking about their current religion (irrespective of whether they are officially members of a particular Christian church by paying church tax). Nonetheless the same survey shows that only 27% of Christians in Switzerland attend church at least monthly, while the majority of Christians seldom go to church. 4% of people questioned state they have a non-Christian religion. 21% are of no religion, and nearly half of them consider themselves Atheists.[5]

Census data

| Religion | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2013 | 2015 | 2016[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 98.7 | 98.4 | 98.3 | 98.0 | 97.8 | 98.8 | 97.5 | 93.7 | 89.2 | 80.5 | 71.8 | 69.9 | 68.0 | 66.9 |

| –Roman Catholic | 42.5 | 40.9 | 41.0 | 40.4 | 41.5 | 45.4 | 46.7 | 46.2 | 46.2 | 42.3 | 38.4 | 38.0 | 37.3 | 36.5 |

| –Swiss Reformed | 56.2 | 57.5 | 57.3 | 57.6 | 56.3 | 52.7 | 48.8 | 45.3 | 39.6 | 33.9 | 27.8 | 26.1 | 24.9 | 24.5 |

| –Other Christian | - | - | - | - | - | 0.7 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.9 |

| Islam | - | - | - | - | - | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.2 |

| Judaism | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Others | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Unaffiliated | - | - | - | - | - | 0.5 | 1.2 | 3.9 | 7.5 | 11.4 | 20.6 | 22.2 | 23.9 | 24.9 |

| No answer | - | - | - | - | - | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Population | 3.753.293 | 3.880.320 | 4.066.400 | 4.265.703 | 4.714.992 | 5.429.061 | 4.575.416 | 4.950.821 | 5.495.018 | 5.868.572 | 6.587.556 | 6.744.794 | 6.907.818 | 6.981.381 |

As in many other European countries, the major Christian confessions are losing members whereas the numbers of unaffiliated and not religious people are growing fast and Muslims are slightly increasing and came to represent a more or less constant share of the population since 2000.

Line chart

Legislation

The Swiss constitution of 1848, written by the victorious pro-union Protestant cantons after the Sonderbundskrieg (Catholic-Separatist Civil War of 1847), consciously defines a consociational state, allowing the peaceful co-existence of Catholics and Protestants.

However, the Catholic Jesuits (Societas Jesu) were banned from all activities in either clerical or pedagogical functions by Article 51 of the Swiss constitution in 1848. The reason was the perceived threat resulting from Jesuit advocacy of traditionalist Catholicism to the stability of the state. In May 1973, 54.9% of Swiss voters approved removing the ban on the Jesuits (as well as Article 52 which banned monasteries and convents from Switzerland).[7]

The settlement restrictions placed on Swiss Jews in various instances between the 14th and 18th centuries were lifted with the revised Swiss Constitution of 1874.

A popular vote in March 1980 on the complete separation of church and state was clearly opposed to such a change, with only 21.1% voting in support, to the effect of the retention of the Landeskirchen system.[8]

In November 2009, 57.5% of Swiss voters approved of a popular initiative to ban the construction of minarets in Switzerland. The four existing Swiss minarets, at mosques in Zürich, Geneva, Winterthur and Wangen bei Olten are not affected by the ban.[9]

Freedom of religion

Full freedom of religion has been guaranteed since the revised Swiss Constitution of 1874 (Article 49). During the Old Swiss Confederacy, there had been no de facto freedom of religion, with persecution of Anabaptists in particular well into the 18th century. Swiss Jews had been given full political rights in 1866, although their right to settle freely was implemented as late as 1879 in the canton of Aargau.

The current Swiss Constitution of 1999 makes explicit both positive and negative religious freedom in Article 15, paragraph 3--which asserts that every person has the right to adhere to a religious confession and to attend religious education—and paragraph 4, which asserts that nobody can be forced to either adhere to a religious confession or to attend religious education, thus explicitly asserting the right of apostasy from a previously held religious belief.

The basic right protected by the constitution is that of public confession of adherence to a religious community and the performance of religious cult activities. Article 36 of the constitution introduces a limitation of these rights if they conflict with public interest or if they encroach upon the basic rights of others. Thus, ritual slaughter is prohibited as conflicting with Swiss animal laws. Performance of cultic or missionary activities or religious processions on public ground may be limited. The Jesuit order was banned from all activity on Swiss soil from 1848 to 1973. The use of cantonal taxes to support cantonal churches has been ruled legal by the Federal Supreme Court.[10] Some commentators have argued that the minaret ban introduced by popular vote in 2009 constitutes a breach of religious freedom.[11]

History

Traces of the pre-Christian religions of the area that is now Switzerland include the Bronze Age "fire dogs". The Gaulish Helvetii, who became part of Gallo-Roman culture under the Roman Empire, left only scarce traces of their religion like the statue of dea Artio, a bear goddess, found near Bern. A known Roman sanctuary to Mercury was on a hill north-east of Baar.[12] St. Peter in Zürich was the location of a temple to Jupiter.

The Bishopric of Basel was established in AD 346; the bishopric of Sion, before 381; the bishopric of Geneva. in c. 400: the bishopric of Vindonissa (now united as the Diocese of Lausanne, Geneva and Fribourg), in 517; and the Diocese of Chur, before 451.

Germanic paganism briefly reached Switzerland with the immigration, from the 6th century, of the Alemanni, who were gradually converted to Christianity during the 6th and 7th centuries, with the establishment of the Bishopric of Constance in c. 585. The Abbey of St. Gall rose as an important center of learning in the early Middle Ages.

The Old Swiss Confederacy was Roman Catholic as a matter of course until the Reformation of the 1520s, which resulted in a lasting split of the Confederacy into Protestantism and Catholicism. This split lead to numerous violent outbreaks in Early Modern times and included the partitioning of the former canton of Appenzell into the Protestant canton of Appenzell Ausserrhoden and Catholic Appenzell Innerrhoden in 1597. The secular Helvetic Republic was a brief intermezzo and tensions immediately resurfaced after 1815, leading to the formation of the modern confederal state in 1848, which recognizes Landeskirchen on a cantonal basis: the Roman Catholic and the Reformed Churches in each canton, and since the 1870s (following the controversies triggered by the First Vatican Council) the Christian Catholic Church in some cantons.

Geneva holds a special place in Protestant history as fundamental parts of John Calvin's religious thought originated there, and was further progressed by Theodore Beza, William Farel and other Reformed theologians. It also served as a haven for persecuted Protestants from France, including Calvin, who became the spiritual leader of the city, himself. Zürich is also important for Protestants, as Huldrych Zwingli, Heinrich Bullinger and other Reformed theologians operated there.

The Jesuits (Societas Jesu) were the subject of a bitter controversy in 19th century Switzerland. The order had been dissolved in 1773 by Clement XIV, but it was re-instated in 1814 by Pius VII.

Over the following years, the Jesuits returned to the Swiss colleges they had owned prior to 1773, in Brig (1814), Sion (1814), Fribourg (1818) and Lucerne (1845), and especially Fribourg became a center of the Council of Trent. The Protestant cantons felt threatened by the re-appearance of the Jesuits and their program of traditionalist Catholicism, which contributed to religious unrest and the formation of the Sonderbund of the Catholic cantons, and at the Tagsatzung of 1844 in vain demanded the expulsion of the Jesuit order from the territory of the Swiss confederacy. The Protestant victory of the Sonderbundskrieg of 1847 led to the realization of such a ban in the 1848 Swiss Constitution, expanded even further in the revised constitution of 1874, so that all activity of Jesuits either in clerical or in educational function was outlawed in Switzerland until 1973, when the paragraph was removed from the constitution by a popular vote.[13]

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Population résidante permanente âgée de 15 ans ou plus selon l'appartenance religieuse" (XLS) (official site) (in German, French, and Italian). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Federal Statistical Office FSO. 31 January 2018. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ↑ "Die Kirchensteuern August 2013" (in German, French, and Italian). Berne: Schweizerische Steuerkonferenz SSK, Swiss Federal Tax Administration FTA, Federal Depertment of Finance FDF. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2014-04-05. , Swiss Federal Tax Administration

- ↑ "Volksabstimmung vom 2. März 1980" (in German, French, and Italian). Berne, Switzerland: Schweizerische Bundeskanzlei. 28 July 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- 1 2 3 Bovay, Claude; Broquet, Raphaël (December 2004), "Introduction", Recensement fédéral de la population 2000 (PDF) (in French), Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Federal Statistical Office FSO, p. 12, ISBN 3-303-16074-0, retrieved 2015-07-31

- ↑ "Being Christian in Western Europe (survey among 24,599 adults (age 18+) across 15 countries in Western Europe)". Pew Research Center. 29 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-05-29.

- 1 2 "Ständige Wohnbevölkerung ab 15 Jahren nach Religionszugehörigkeit" (XLS) (official site) (in German, French, and Italian). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Federal Statistical Office FSO. 31 January 2017. Retrieved 2018-07-15. The report contains data of the censuses from 1910 to 2015.

- ↑ "Volksabstimmung vom 20.05.1973" (in German, French, and Italian). Schweizerische Bundeskanzlei. 20 May 1973. Retrieved 2015-06-08.

- ↑ "Volksabstimmung vom 02.03.1980" (in German, French, and Italian). Schweizerische Bundeskanzlei. 2 March 1980. Retrieved 2015-06-08.

- ↑ "Abstimmungen – Indikatoren: Eidgenössische Volksabstimmung vom 29. November 2009" (in German, French, and Italian). Statistik Schweiz. 29 November 2009. Retrieved 2015-06-08.

- ↑ BGE 107 Ia 126, 130 (1981)

- ↑ Malte Lehming (30 November 2009). "Ein schwarzer Tag". Zeit Online. Hamburg, Germany. Retrieved 2015-06-08.

- ↑ Baarburg at 47°12′18″N 8°33′18″E / 47.205°N 8.555°E; Tages-Anzeiger 5 June 2008

- ↑ Franz Xaver Bischof: Jesuits in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 2008.

Bibliography

- Marcel Stüssi (2012). Models of Religious Freedom: Switzerland, the United States, and Syria by Analytical, Methodological, and Eclectic Representation. ReligionsRecht im Dialog. 12. Zurich: LIT. pp. 375 ff. ISBN 978-3-643-80118-0.

- Christoph Uehlinger: Religion in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 2011-12-23.

- Jakob Frey: Church tax in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 2007-08-13.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Religion in Switzerland. |

.svg.png)