Laz people

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 45,000 to 1.6 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,000[4] | |

| 1,000 to 1,500[5] | |

| 160[6] | |

| Languages | |

| Laz, Georgian, Turkish | |

| Religion | |

| Turkey Majority Sunni Islam[7]Georgia Majority Georgian Orthodox[8] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mingrelians, Svans and other groups of Kartvelians | |

| Laz people |

|---|

|

|

|

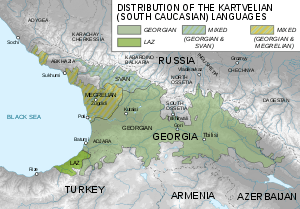

The Laz people or Lazi (Laz: Lazi, ლაზი; Georgian: ლაზი, lazi; or ჭანი, ch'ani; Turkish: Laz) are an indigenous Kartvelian-speaking ethnic group[9] inhabiting the Black Sea coastal regions of Turkey and Georgia.[10]

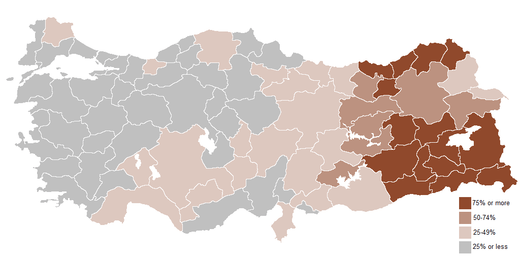

Estimates of the total population of the Laz people today vary drastically, with numbers as low as 45,000 to as high as 1.6 million people, with the majority living in northeast Turkey. The Laz speak the Laz language, a member of the same Kartvelian language family as Georgian, Svan, and Mingrelian.[11][12] The Laz language is classified as endangered by UNESCO, with an estimated 130,000 to 150,000 speakers in 2001.[13]

Etymology

The ancestors of the Laz people are cited by many classical authors from Scylax to Procopius and Agathias, but the Laz (Greek: Λαζοί) themselves are cited by Pliny around the 2nd century BC,[14][15] The ethnonym "Laz" is unhesitatingly linked to a Svan toponym La-zan (i.e. La = territorial prefix + Zan).

By the 6th century, the Colchians of Pontus were known as the Tzanni (Ancient Greek: Τζάννοι), at the same time when the Caucasian state of Lazica (or Egrisi in Georgian sources) existed on the Phasis valley basin. According to Procopius, the Byzantine emperor Justinian I subdued Tzanni in the 520s and converted them to Christianity.[16] When the ancient metropolis, Phasis, was lost by the Byzantine Empire, Trebizond became the Metropolitan bishop of Lazica, since then the name Lazi appears the general Greek name for the southern Colchian tribes (Greek: Τζανοί, translit. Tzanoi) lying outside of the direct control of the Lazic Kingdom.

The Pontic Lazi, which were incorporated within the Byzantine Empire, and differed from the Caucasian Lazi, or Megrelians, have retained the old name "Lazi" till today.

Origins

The Laz are ethnically a branch of the Georgians. Many modern theories suggest that the ancestors of the Laz-Mingrelians constituted the dominant ethnic and cultural presence in the south-eastern Black Sea region in antiquity, and hence played a significant role in the ethnogenesis of the modern Georgians.[17][18]

History

Antiquity

In the 13th century BC, the Kingdom of Colchis was formed as a result of the increasing consolidation of the tribes inhabiting the region, which covered modern western Georgia and Turkey's north-eastern provinces of Trabzon and Rize. In 8th century, several Greek trading colonies were established along the shores of the Black Sea.

By the 6th century BC, the tribes living in the southern Colchis (Macrones, Moschi, Marres etc.) were incorporated into the nineteenth Satrapy of Persia. The Achaemenid Empire was defeated by Alexander the Great, however following of Alexander's death a number of separate kingdoms were established in Anatolia, including Pontus, in the corner of the south-eastern Black Sea, ruled by Mithridates. The very small number of Hellenistic Greek inscriptions that have been found anywhere in Pontus suggest that Greek culture did not substantially penetrate beyond the coastal cities and the court.[19]

As a result of the brilliant Roman campaigns led by the generals Pompey and Lucullus, the kingdom of Pontus was completely destroyed by the Romans and all its territory, including Colchis, was incorporated into the Roman Empire. The former southern provinces of Colchis were reorganized into the Roman province of Pontus Polemoniacus, while the northern Cholchis became the Roman province of Lazicum. By the mid-3rd century, the Lazi tribe came to dominate most of Colchis, establishing the kingdom of Lazica.

Greek colonization was restricted to the coast, and in later ages Roman control remained likewise only nominal over the tribes of the interior.[20] The coastal regions, however, belonged to the Roman province of Pontus Polemoniacus.

Middle Ages

During the reign of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (c. 527–565) the warlike tribes of the interior Pontus, called Sannoi or Tzannoi, the ancestors of modern Laz people, were subdued, Christianized and brought to central rule.[21] Locals began to have closer contact with the Greeks and acquired various Hellenic cultural traits, including in some cases the language.

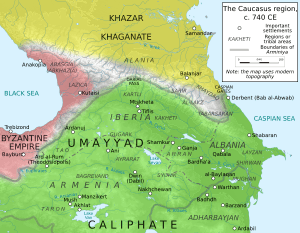

From 542 to 562, Lazica was a scene of the protracted rivalry between the Eastern Roman and Sassanid empires, culminating in the Lazic War. Emperor Heraclius's offensive in 628 AD brought victory over the Persians and ensured Roman predominance in Lazica until the invasion and conquest of the Caucasus by the Arabs in the second half of the 7th century.

In the 7th century Lazica fell to the Muslim conquest, however in the 8th century combined Lazic and Abasgian forces successfully repelled the Arab occupation. In 780 Lazica was incorporated to kingdom of Abkhazia via a dynastic union, the latter led the unification of Georgian monarchy in the 11th century, thus ousting the Pontic Lazs from western Georgia; thereafter, the Lazs lived under nominal Byzantine suzerainty in the theme of Chaldia, with its capital at Trebizond, governed by the native semi-autonomous rulers, like the Gabras family.[22] According to the 10th century Arab geographer Abul Feda city of Trebizond was regarded as being largely a Lazian port. Following the Seljuk Turks invasion, there has been continuous influx of Armenians resulting partial armenization of the local Tzan population and formation of new Hemshin identity.[23]

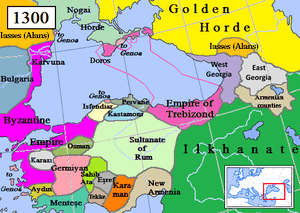

With the Georgian intervention in Chaldia and collapse of Byzantine Empire in 1204, Empire of Trebizond was established along the southwestern coast of the Black Sea, populated by a large Lazian-speaking population.[24] In the eastern part of the same empire, an autonomous coastal theme of Greater Lazia was established.[25] Byzantine authors, such as Pachymeres, and to some extent Trapezuntines such as Lazaropoulos and Bessarion, regarded the Trapezuntian Empire as being no more than a Lazian border state.[26] Though Greek in higher culture, the rural areas of Trebizond empire appear to have been predominantly Laz in ethnic composition.[27] Laz family names, with Hellenized terminations, are noticeable in the records of the mediaeval empire of Trebizond, and it is perhaps not too venturesome to suggest that the antagonism between the "town-party" and the "country-party," which existed in the politics of "the Empire," was in fact a national antagonism of Laz against Greek.

In 1282, kingdom of Imereti besieged Trebizond, however after the failed attempt to take the city, the Georgians occupied several provinces and all the Trebizontine province of Lazia threw off its allegiance to the king of the 'Iberian' and 'Lazian' tribes and united itself with the Georgian Kingdom of Imereti.

Early Modern era

Laz populated area was often contested by different Georgian principalities, however through Battle of Murjakheti (1535), Principality of Guria finally ensured control over it, until 1547, when it was conquered by resurgent Ottoman forces and reorganized into the Lazistan sanjak as part of eyalet of Trabzon.

After the Ottoman conquest of Trebizond Empire and later Ottoman invasion of Guria in 1547, Ottomans fought for three centuries to destroy the Christian-Georgian consciousness of the Laz people. Local orthodox inhabitants, once subordinated to the Georgian Orthodox Church, had to obey Patriarchate of Constantinople. Part of the native population were target of the Ottoman Islamization policy and gradually converted to Islam, while the second part of the people who remained orthodox subordinated to the Greek Church, thus gradually becoming Greeks, the process known as Hellenization of Laz people. Lazs who were under the control of Constantinople, soon lost their language and self-identity as they became Greeks and learned Greek, especially Pontic dialect of Greek language, although native language was preserved by Lazs who had become Muslims.

Not only the Pashas (governors) of Trabzon until the 19th century, but real authority in many of the cazas (districts) of each sanjak by the mid-17th century lay in the hands of relatively independent native Laz derebeys ("valley-lords"), or feudal chiefs who exercised absolute authority in their own districts, carried on petty warfare with each other, did not owe allegiance to a superior and never paid contributions to the sultan. This state of insubordination was not really broken until the assertion of Ottoman authority during the reforms of the Osman Pasha in 1850s.

In 1547, Ottomans built coastal fortress of Gonia, an important Ottoman outpost in southwestern Georgia,[28][29] which served as capital of Lazistan; then Batum until it was acquired by the Russians in 1878, throughout the Russo-Turkish War, thereafter, Rize became the capital of the sanjak. The Muslim Lazs living near the war zones in Batumi Oblast were subjected to ethnic cleansing; many Lazes living in Batumi fled to the Ottoman Empire, settling along the southern Black Sea coast to the east of Samsun and Marmara region.

Around 1914 Ottoman policy towards the Christian population shifted; state policy was since focused to the forceful migration of Christian Pontic Greek and Laz population living in coastal areas, close to the Turkish-Russian front to the Anatolian hinterland. In the 1920s Christian population of the Pontus were expelled to Greece.

In 1917, after the Russian Revolution, Lazs became citizents of Democratic Republic of Georgia, and eventually became Soviet citizens after the Red Army invasion of Georgia in 1921. Simultaneously, a treaty of friendship was signed in Moscow between Soviet Russia and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, whereby southern portions of former Batumi oblast - later known as Artvin, was awarded to Turkey, which renounced its claims to Batumi.

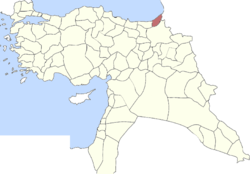

The autonomous Lazistan sanjak existed until the end of the empire in 1923. the designation of the term of Lazistan was officially banned in 1926, by the Kemalists.[30] Lazistan was divided between Rize and Artvin provinces.

Modern

Most Laz people today live in Turkey, but the Laz minority group has no official status in Turkey. The number of the Laz speakers is decreasing, and is now limited chiefly to the Rize and Artvin areas.

Self-identification

Over time the Laz living on either side of the frontier have developed different conceptions of what it means to be Laz. Today, most of those living in Turkey do not consider themselves Turkish, but uphold their Laz identity as a separate one.[31] In contrast, Laz identity in Georgia has largely merged with a Georgian identity, and the meaning of "Laz" is seen as merely a regional category.[32] At the same time, in Turkey, the term Laz is a 'folk' definition for people of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds originating from the Black Sea Region. Officially, the Laz people are not recognized as a minority. Thus, many Turks do not even know about their diverse existence and falsely call the inhabitants of the Black Sea coast as the "Lazlar". Within the last decade more and more intellectual Laz people realized that the disappearance of their language would lead to the disappearance of their identity and tried to preserve their inherited culture through political empowerment, linguistic education, and music and poetry.

Population and geographical distribution

The total population of the Laz today is only estimated, with numbers ranging widely. The majority of Laz live in Turkey, where the national census does not record ethnic data on minor populations.[33]

Settlements

| Country / region | Official data | Estimate | Concentration | Article |

|---|---|---|---|---|

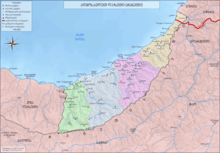

| 500.000[34][35][36] | 1.6 million[37] | Rize: Pazar, Ardeşen, and Fındıklı districts.

Artvin: Arhavi and Hopa. minorities in: Çamlıhemşin, Borçka, and İkizdere districts. |

Laz people in Turkey | |

| 2,000[38] | Tbilisi Adjara: Sarpi, Kvariati, Gonio, Makho, Batumi and Kobuleti. |

Laz people in Georgia | ||

| 1,000-1,500[39] (Germany 1987) |

Belgium, France and Germany.[4] | Laz people in Germany | ||

| 160[6] | 2,000 | Moscow | Laz people in Russia |

Area

The majority of the Laz today live in an area they call Laziǩa, Lazistan, Lazeti or Lazona name of the cultural region traditionally inhabited by the Laz people in modern northeast Turkey and southwest Georgia. Geographically, Lazistan consists of a series of narrow, rugged valleys extending northward from the crest of the Pontic Alps (Turkish: Anadolu Dağları), which separate it from the Çoruh Valley, and stretches east-west along the southern shore of the Black Sea. Lazistan is a virtually a forbidden term in Turkey.[upper-alpha 1] the name was considered to be an 'unpatriotic' invention of ancien regime.[30]

Laz ancestral lands are not well-defined and there is no official geographic definition for the boundaries of Lazistan. However, the following provinces are usually included:

Economy

Historically, Lazistan was known for producing hazelnuts.[40] Lazistan also produced zinc, producing over 1,700 tons in 1901.[41] The traditional Laz economy was based on agriculture—carried out with some difficulty in the steep mountain regions and also on the breeding of sheep, goats, and cattle. Orchards were tended and bees were kept, and the food supply was augmented by hunting. The Laz are good sailors and also practise agriculture rice, maize, tobacco and fruit-trees. The only industries were smelting, celebrated since ancient times, and the cutting of timber used for shipbuilding.

Culture

Over the past 20 years, there has been an upsurge of cultural activities aiming at revitalizing the Laz language, education and tradition. Kâzım Koyuncu, who in 1998 became the first Laz musician to gain mainstream success, contributed significantly to the identity of the Laz people, especially among their youth.[42]

The Laz Cultural Institute was founded in 1993 and the Laz Culture Association in 2008, and a Laz cultural festival was established in Gemlik.[6][43] The Laz community successfully lobbied Turkey's Education Ministry to offer Laz-language instruction in schools around the Black Sea region. In 2013, the Education Ministry added Laz as a four-year elective course for secondary students, beginning in the fifth grade.[44]

Language

Lazuri is a complex and morphologically rich tongue belonging to the South Caucasian language family whose other members are Mingrelian, Svanetian, and Georgian. The Laz language does not have a written history, thus Turkish and Georgian serve as the main literary languages for the Laz people. Their folk literature has been transmitted orally and has not been systematically recorded. The first attempts at establishing a distinct Laz cultural identity and creating a literary language based on the Arabic alphabet was made by Faik Efendisi in the 1870s, but he was soon imprisoned by the Ottoman authorities, while most of his works were destroyed. During a relative cultural autonomy granted to the minorities in the 1930s, the written Laz literature—based on the Laz script—emerged in Soviet Georgia, strongly dominated by Soviet ideology. The poet Mustafa Baniṣi spearheaded this short-lived movement, but an official standard form of the tongue was never established.[45] Since then, several attempts have been made to render the pieces of native literature in the Turkish and Georgian alphabets. A few native poets in Turkey such as Raşid Hilmi and Pehlivanoğlu have appeared later in the 20th century.

Religion

One of the chief tribes of ancient kingdom of Colchis, the Laz were converted to Christianity while living under the Byzantine Empire and the Kingdom of Georgia. Trebizond, which was the only diocese established far in the past, Cerasous and Rizaion in Lazia, both formed as upgraded bishoprics. All three dioceses survived the Ottoman conquest (1461) and generally operated until the 17th century, when the dioceses of Cerasous and Rizaion were abolished. The diocese of Rizaion and the bishopric of Of were abolished at the time due to the Islamisation of the Lazs. Most of them subsequently converted to Sunni Islam.[46][47]

There are also a few Christian Laz in the Adjaria region of Georgia who have converted to Christianity.[48]

Mythology

Famous for its saga and myths and bounded by the Black Sea and the Caucasian Mountains, the ancient region of Colchis spreads out from West Georgia to Northeast Turkey. The famous tale in Greek mythology of the Golden Fleece in which Jason and the Argonauts stole the Golden Fleece from King Aeetes, with the help of his daughter Medea, has brought Colchis into the history books.

Festival

Kolkhoba is an ancient Laz festival. It is held at the end of August or at the beginning of September in Sarpi village, Khelvachauri District. Festival has revived the former lifestyle of Lazeti residents and moments of human relations typical to the times of ancient Greece and Colchis related to the Argonauts journey to Colchis. During the celebration of Kolkhoba theater performances are followed by a variety of activities and it is considered one of the main public festivals.

Music

The national instruments include guda (bagpipe), kemenche (spike fiddle), zurna (oboe), and doli (drum). In the 1990s and 2000s, the folk-rock musician Kâzım Koyuncu attained to significant popularity in Turkey and toured Georgia. Koyuncu, who died of cancer in 2005, was also an activist for the Laz people and has become a cultural hero.[49]

Dance

The Laz are noted for their folk dances, called the Horon dance of the Black Sea, originally of pagan worship which was to become a sacred ritual dance. There are many different types of this dance in different regions. Horon is related to those performed by the Ajarians known as Khorumi. These may be solemn and precise, performed by lines of men, with carefully executed footwork, or extremely vigorous with the men dancing erect with hands linked, making short rapid movements with their feet, punctuated by dropping to a crouch. The women's dances are graceful but more swift in movement than those encountered in Georgia. In Greece such dances are still associated with the Pontic Greeks who emigrated from this region after 1922.

Traditional clothing

The traditional Laz men's costume consists of a peculiar bandanalike kerchief covering the entire head above the eyes, knotted on the side and hanging down to the shoulder and the upper back; a snug-fitting jacket of coarse brown homespun with loose sleeves; and baggy dark brown woolen trousers tucked into slim, knee-high leather boots. The women's costume was similar to the wide-skirted princess gown found throughout Georgia but worn with a similar kerchief to that of the men and with a rich scarf tied around the hips. Laz men crafted excellent homemade rifles and even while at the plow were usually seen bristling with arms: rifle, pistol, powder horn, cartridge belts across the chest, a dagger at the hip, and a coil of rope for trussing captives.

Cuisine

Laz cuisine specialities include:

- Mıhlama – a filling corn meal, butter, and cheese fondue;

- Hamsi pilavı – spiced rice enclosed in fried Black Sea anchovies;

- Kuru fasulye – white beans in a tomato sauce;

- Laz böreği – a custard filled baklava like dessert;

- Karadeniz pidesi – an elongated and closed form of the popular pide dish.

Discrimination

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the leader of the early decades of the Republic, aimed to create a nation state (Turkish: Ulus) from the Turkish remnants of the Ottoman Empire. During the first three decades of the Republic, efforts to Turkify geographical names were a recurring theme. Imported maps containing references to historical regions such as Armenia, Kurdistan, or Lazistan (the official name of the province of Rize until 1921) were prohibited (as was the case with Der Grosse Weltatlas, a map published in Leipzig).

Cultural assimilation into the Turkish culture has been high, and Laz identity was oppressed during the days of Ottoman and Soviet Rule. One of the pivotal moments was in 1992, when the book Laz History (Lazların tarihi) was published. The authors had failed to have it published in 1964.[42]

Notable Lazs

|

|

Gallery

Çürüksulu Ali Pasha and Ottoman Georgian and Laz peoples. Pasha was a descendant of the Georgian noble family of the Tavdgiridze.

Çürüksulu Ali Pasha and Ottoman Georgian and Laz peoples. Pasha was a descendant of the Georgian noble family of the Tavdgiridze. Postcard by Osman Nuri featuring Laz dancers in national costume in Trabzon, Turkey.

Postcard by Osman Nuri featuring Laz dancers in national costume in Trabzon, Turkey.- Laz men from Trabzon, 1910's

Mustapha - Moslem from Batum circa 1852

Mustapha - Moslem from Batum circa 1852 Engravings from Le Tour du Monde based on drawing by Théophile Deyrolle, who traveled in Turkey and Georgia in the 1870s, documenting, among other things, medieval Georgian monuments on the territory of the Ottoman Empire.

Engravings from Le Tour du Monde based on drawing by Théophile Deyrolle, who traveled in Turkey and Georgia in the 1870s, documenting, among other things, medieval Georgian monuments on the territory of the Ottoman Empire. Soldiers in traditional Trebizond (Trabzon, Turkey) clothing, Constantinople, 1900s.

Soldiers in traditional Trebizond (Trabzon, Turkey) clothing, Constantinople, 1900s. Laz people in 1900s

Laz people in 1900s Russia in Asia. Lazian Militia., ca. 1918 - ca. 1919

Russia in Asia. Lazian Militia., ca. 1918 - ca. 1919 Extracted picture with caption: „Einwohner aus Lazistan.“

Extracted picture with caption: „Einwohner aus Lazistan.“

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law (Law No. 3713 amended by Law No. 4126) reads, “No one may engage in written and oral propaganda aimed at disrupting the indivisible integrity of the State of the Turkish Republic, country, and nation. [… ] Those who engage in such deeds will be sentenced to from one to three years in prison and given a heavy fine… ”. This article means that those who orally or in print make use of words such as Lazistan or Kurdistan risk prosecution."

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Laz people. |

References

- ↑ Bülent Günal (20 December 2011). "67 milletten insanımız var!" (in Turkish). Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "TURKEY - General Information". U.S. English Foundation Research. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ↑ Jak Yakar. "Ethnoarchaeology of Anatolia: Rural Socio-economy in the Bronze and Iron Ages". Institute of Archaeology. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Bedrohte Sprachen: Menschenrechtsreport" [Endangered Languages Human Rights Report] (PDF) (in German). 63. Society for Threatened Peoples. March 2010: 53.

- ↑ Census (1987)

- 1 2 3 "Национальный состав населения" [2010 Census: Ethnic composition of the population] (PDF) (in Russian). Russian Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Roger Rosen, Jeffrey Jay Foxx, The Georgian Republic, Passport Books (September 1991)

- ↑ kavkazoved.info, ЛАЗЫ СССР И ГРУЗИИ: ПЕРИПЕТИИ ИСТОРИЧЕСКИХ СУДЕБ (in Russian)

- ↑ James S. Olson (1994). Lee Brigance Pappas, Nicholas Charles Pappas, eds. An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Greenwood. p. 436.

- ↑ 1 Minorsky, V. "Laz." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E . Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2010.

- ↑ Dalby, A. (2002). Language in Danger; The Loss of Linguistic Diversity and the Threat to Our Future. Columbia University Press. p. 38.

- ↑ BRAUND, D., Georgia in antiquity: a history of Colchis and Transcaucasian Iberia 550 BC – AD 562, Oxford University Press, p. 93

- ↑ "World Language Atlas". UNESCO. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Pliny, NH 6.4.12

- ↑ Braund (1994), p. 157, fn. 24.

- ↑ Procopius Bell. Pers. i. 15, Bell. Goth. iv. 2, de Aed. iii. 6.

- ↑ Miniature Empires: A Historical Dictionary of the Newly Independent States, James Minahan, p. 116

- ↑ Cyril Toumanoff, Studies in Christian Caucasian History, p 80

- ↑ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/pontus

- ↑ Talbert 2000, p. 1226.

- ↑ Evans 2000, p. 93.

- ↑ Hewsen, 47

- ↑ Simonian. "Hamshen Before Hemshin", pp. 21-22.

- ↑ Mikaberidze, A. (2015). Historical dictionary of Georgia. 2nd ed. Lanham, MD, United States: ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD, p.634.

- ↑ Thys-Şenocak, Lucienne. Ottoman Women Builders. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006.

- ↑ Bryer 1967, 179.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Laz

- ↑ Bagrationi, Vakhushti (1976). Nakashidze, N.T., ed. История Царства Грузинского [History of the Kingdom of Georgia] (PDF) (in Russian). Tbilisi: Metsniereba. pp. 133–135.

- ↑ Church, Kenneth (2001). From dynastic principality to imperial district: the incorporation of Guria into the Russian Empire to 1856 (Ph.D.). University of Michigan. pp. 127–129.

- 1 2 Thys-Şenocak, Lucienne. Ottoman Women Builders. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006. Print.

- ↑ Chai-khana.org; The Laz: Two Tales of One People , Irakli Dzneladze

- ↑ Minorsky, V. "Laz." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E . Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2010.,

- ↑ Silvia Kutscher (2008). "The language of the Laz in Turkey: Contact-induced language change or gradual loss?" (PDF). Turkic Languages. 12 (1). Retrieved 31 January 2015.

Due to a lack of census information on minorities (aside from a small number of exceptions such as the Greek or Armenian populations), the actual number of Laz living in Turkey can only be estimated

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Orient

- ↑ ecoi.net

- ↑ http://www.usefoundation.org/view/865

- ↑ Bülent Günal (20 December 2011). "67 milletten insanımız var!" (in Turkish). Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Laz". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 2012-02-15.

- ↑ https://www.ethnologue.com/13/countries/Turk.html

- ↑ Prothero, W.G. (1920). Armenia and Kurdistan. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 52.

- ↑ Prothero, W.G. (1920). Armenia and Kurdistan. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 73.

- 1 2 Ismail Güney Yılmaz (7 January 2015). "90'lar: Laz Kültür ve Kimlik Hareketinin Doğuşu" [1990s: The Birth of the Laz Culture and Identity Movement] (in Turkish). Lazebura. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Kâmil Aksoylu (3 July 2013). "Laz Kültürü Hareketi̇ 93 Süreci̇nden Laz Ensti̇tüsüne" (in Turkish). Lazca.org. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Lazuri classes to begin in secondary schools in Turkey". Anadolou. 14 September 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Iksander Tsitashi (1939). Лазская литература [Laz literature]. Литературная энциклопедия (Encyclopedia of Literature) (in Russian). Moscow.

- ↑ "Ethnoarchaeology of Anatolia: rural socio-economy in the Bronze and Iron Ages". Jak Yakar. Google Books. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

Formerly Christians, they converted to Sunni Islam a little over four centuries ago.

- ↑ Özhan Öztürk. Pontus. Genesis Yayınları. İstanbul, 2009. s. 737-38, 778

- ↑ Roger Rosen, Jeffrey Jay Foxx (September 1991) The Georgian Republic, Passport Books, Lincolnwood, IL ISBN 978-0-84429-677-7

- ↑ Hake, Sabine; Mennel, Barbara (2012-10-01). Turkish German Cinema in the New Millennium: Sites, Sounds, and Screens. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-769-1.

Sources

- Andrews, Peter (ed.). 1989. Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. pp. 497–501.

- Benninghaus, Rüdiger. 1989. "The Laz: an example of multiple identification". In: Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey, edited by P. Andrews.

- Bryer, Anthony. 1969. The last Laz risings and the downfall of the Pontic Derebeys, 1812–1840, Bedi Kartlisa 26. pp. 191–210.

- Hewsen, Robert H. Laz. World Culture Encyclopedia. Accessed on September 1, 2007.

- Negele, Jolyon. Turkey: Laz Minority Passive In Face Of Assimilation. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 25 June 1998

External links

- Laz Culture Association (Turkish)

- Lazca.org: Culture, News and Information (Turkish)

- Lazebura.com: Culture, News and Information (Turkish)

- Lazuri.com: Culture Portal (Turkish)