National People's Congress

| National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China 中华人民共和国全国人民代表大会 Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó Quánguó Rénmín Dàibiǎo Dàhuì | |

|---|---|

| 13th National People's Congress | |

.svg.png) | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Founded | 1954 |

| Leadership | |

Presidium of NPC |

Presidium of the National People's Congress (Temporary, Elected before every session of NPC opens and finished after every session concludes) [1] Since 4 March 2018 (at a preparatory meeting for 1st session of 13th NPC) |

|

Zhanshu Li, Xi Chen, Chen Wang, Jianming Cao, Chunxian Zhang, Yueyue Shen, Bingxuan Ji, Alecken Eminbahe, CPC Zhu Chen, CPWDP Since 4 March 2018 (at 1st presidium meeting of 1st session of 13th NPC) | |

Secretary-General of NPC | |

| Structure | |

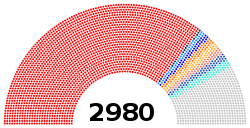

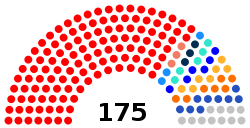

| Seats |

Since 5 March 2018: 2980 Members of NPC 175 Members of NPCSC |

| |

NPC political groups |

Since 24 February 2018:

United Front, Pro-Beijing camp (Hong Kong) and Independent (861): |

| |

NPCSC political groups |

Since 18 March 2018:

United Front, and Independent (54): |

Length of term | 5 years |

| Elections | |

NPC voting system | Party-list proportional representation and Approval voting[2] |

| Party-list proportional representation and Approval voting[2] | |

NPC last election | December 2017 – January 2018 |

NPCSC last election | 14 March 2013 |

NPC next election | Late 2022 – early 2023 |

NPCSC next election | 18 March 2018 |

| Redistricting | Standing Committee of the National People's Congress |

| Meeting place | |

|

| |

| Great Hall of the People, Xicheng District, Beijing City, People's Republic of China | |

| Website | |

| http://www.npc.gov.cn | |

| National People's Congress | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 全国人民代表大会 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 全國人民代表大會 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Nationwide People Representative Assembly | ||||||

| |||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||

| Tibetan | རྒྱལ་ཡོངས་མི་དམངས་འཐུས་མི་ཚོགས་ཆེན་ | ||||||

| |||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||

| Zhuang | Daengx Guek Yinzminz Daibyauj Daihhoih | ||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Бөх улсын ардын төлөөлөгчдийн их хуралд | ||||||

| Mongolian script |

ᠪᠦ᠋ᠬᠦ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ ᠤᠨ ᠠᠷᠠᠳ ᠤᠨ ᠲᠥᠯᠥᠭᠡᠯᠡᠭᠴᠢᠳ ᠦᠨ ᠶᠡᠬᠡ ᠬᠤᠷᠠᠯ | ||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||

| Uyghur |

ھۆكۈمىتىنى قۇرۇش توغرىسىدىكى تەكلىۋى | ||||||

| |||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||

| Manchu script |

ᡤᡠᠪᠴᡴᡳ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ ᡳ ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡶᡠᠨᡩᡝᠯᡝᠨ ᠠᠮᠪᠠ ᡳᠰᠠᡵᡳᠨ (ᡰᡳᡝᠨᡩᠠ) | ||||||

| Romanization | Gubchi gurun-i niyalmairgen fundelen amba isarin (Renda) | ||||||

The National People's Congress (usually abbreviated NPC) is the national legislature of the People's Republic of China. With 2,980 members in 2018, it is the largest parliamentary body in the world.[3]

Under China's Constitution, the NPC is structured as a unicameral legislature, with the power to legislate, the power to oversee the operations of the government, and the power to elect the major officers of state. However, the NPC has been described as a "rubber stamp," having "never rejected a government proposal" in its history.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13]

The NPC is elected for a term of five years. It holds annual sessions every spring, usually lasting from 10 to 14 days, in the Great Hall of the People on the west side of Tiananmen Square in Beijing. The NPC's sessions are usually timed to occur with the meetings of the National Committee of the People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a consultative body whose members represent various social groups. As the NPC and the CPPCC are the main deliberative bodies of China, they are often referred to as the Lianghui (Two Sessions).[14] [15]

According to the NPC, its annual meetings provide an opportunity for the officers of state to review past policies and present future plans to the nation.[16]

Powers and duties

In theory, the NPC is the highest organ of state power in China, and all four PRC constitutions have vested it with great lawmaking powers. However, in practice it usually acts as a rubber stamp for decisions already made by the state's executive organs and the Communist Party of China.[17] One of its members, Hu Xiaoyan, told the BBC in 2009 that she has no power to help her constituents. She was quoted as saying, "As a parliamentary representative, I don't have any real power."[18] In 2014, the CPC pledged to protect the NPC's right to "supervise and monitor the government," provided that the NPC continue to "unswervingly adhere" to the party's leadership.[19] Since the 1990s, the NPC has become a forum for mediating policy differences between different parts of the Party, the government, and groups of society.

There are mainly four functions and powers of the NPC:[20]

1. To amend the Constitution and oversee its enforcement

Only the NPC has the power to amend the Constitution. Amendments to the Constitution must be proposed by the NPC Standing Committee or 1/5 or more of the NPC deputies. In order for the Amendments to become effective, they must be passed by 2/3 majority vote of all deputies.

2. To enact and amend basic law governing criminal offences, civil affairs, state organs and other matters

3. To elect and appoint members to the central state organs

The NPC elects the Chairman, Vice Chairmen, Secretary-General and other members of its Standing Committee. It also elects the President of the People's Republic of China and the Vice President of the People's Republic of China. NPC also appoints the Premier of the State Council and many other crucial officials to the central state organs. The NPC also has the power to remove the above-mentioned officials from the office.

4. To determine major state issues

This includes examining and approving the report on the plan for national economic and social development and on its implementation, report and central budget, and more. The establishment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the Macao Special Administrative Region, Hainan Province and Chongqing Municipality and the building of the Three Gorges Project on the Yangtze River were all decided by the NPC.

The drafting process of NPC legislation is governed by the Organic Law of the NPC (1982) and the NPC Procedural Rules (1989). It begins with a small group, often of outside experts, who begin a draft. Over time, this draft is considered by larger and larger groups, with an attempt made to maintain consensus at each step of the process. By the time the full NPC or NPCSC meets to consider the legislation, the major substantive elements of the draft legislation have largely been agreed to. However, minor wording changes to the draft are often made at this stage. The process ends with a formal vote by the Standing Committee of the NPC or by the NPC in a plenary session.

The NPC mainly exists to give legal sanction to decisions already made at the highest levels of the government. However, it is not completely without influence. It functions as a forum in which legislative proposals are drafted and debated with input from different parts of the government and outside technical experts. However, there are a wide range of issues for which there is no consensus within the Party and over which different parts of the party or government have different opinions. Over these issues the NPC has often become a forum for debating ideas and for achieving consensus.

In practice, although the final votes on laws of the NPC often return a high affirmative vote, a great deal of legislative activity occurs in determining the content of the legislation to be voted on. A major bill such as the Securities Law can take years to draft, and a bill sometimes will not be put before a final vote if there is significant opposition to the measure.[21]

One important constitutional principle which is stated in Article 8 of the Legislation Law of the People's Republic of China is that an action can become a crime only as a consequence of a law passed by the full NPC and that other organs of the Chinese government do not have the power to criminalize activity. This principle was used to overturn police regulations on custody and repatriation and has been used to call into question the legality of re-education through labor.In practice, there is no mechanism to verify constitutionality of statute laws, meaning that local administrations could bypass the constitution through Administrative laws.

Proceedings

The NPC meets for about two weeks each year at the same time as the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, usually in the Spring. The combined sessions have been known as the two meetings. Between these sessions, power is exercised by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress which contains about 150 members.

The sessions have become media events because it is at the plenary sessions that the Chinese leadership produces work reports. Although the NPC has thus far never failed to approve a work report or candidate nominated by the Party, these votes are no longer unanimous. It is considered extremely embarrassing for the approval vote to fall below 70%, which occurred several times in the mid-1990s. More recently, work reports have been vetted with NPC delegates beforehand to avoid this embarrassment.

In addition, during NPC sessions the Chinese leadership holds press conferences with foreign reporters, and this is one of the few opportunities Western reporters have of asking unscripted questions of the Chinese leadership.

A major bill often takes years to draft, and a bill sometimes will not be put before a final vote if there is significant opposition to the measure. An example of this is the Property Law of the People's Republic of China which was withdrawn from the 2006 legislative agenda after objections that the law did not do enough to protect state property. China's laws are usually submitted for approval after at most three reviews at the NPC Standing Committee. However, the debate of the Property Law has spanned nine years, receiving a record seven reviews at the NPC Standing Committee and stirring hot debates across the country. The long-awaited and highly contested Property Law was finally approved at the Fifth Session of the Tenth National People's Congress (NPC) on 16 March. Among the 2,889 deputies attending the closing session, 2,799 voted for it, 52 against it, 37 abstained and one didn't vote.

Election and membership

The NPC consists of about 3,000 delegates. Delegates to the National People's Congress are elected for five-year terms via a multi-tiered representative electoral system. Delegates are elected by the provincial people's assemblies, who in turn are elected by lower level assemblies, and so on through a series of tiers to the local people's assemblies which are directly elected by the electorate.

There is a limit on the number of candidates in proportion to the number of seats available. At the national level, for example, a maximum of 110 candidates are allowed per 100 seats; at the provincial level, this ratio is 120 candidates per 100 seats. This ratio increases for each lower level of people's assemblies, until the lowest level, the village level, has no limit on the number of candidates for each seat. However, the Congress website says "In an indirect election, the number of candidates should exceed the number to be elected by 20% to 50%."

Membership of previous National People's Congresses

| Congress | Year | Total deputies | Female deputies | Female % | Minority deputies | Minority % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 1954 | 1226 | 147 | 12 | 178 | 14.5 |

| Second | 1959 | 1226 | 150 | 12.2 | 179 | 14.6 |

| Third | 1964 | 3040 | 542 | 17.8 | 372 | 12.2 |

| Fourth | 1975 | 2885 | 653 | 22.6 | 270 | 9.4 |

| Fifth | 1978 | 3497 | 742 | 21.2 | 381 | 10.9 |

| Sixth | 1983 | 2978 | 632 | 21.2 | 403 | 13.5 |

| Seventh | 1988 | 2978 | 634 | 21.3 | 445 | 14.9 |

| Eighth | 1993 | 2978 | 626 | 21 | 439 | 14.8 |

| Ninth | 1998 | 2979 | 650 | 21.8 | 428 | 14.4 |

| Tenth | 2003 | 2985 | 604 | 20.2 | 414 | 13.9 |

| Eleventh | 2008 | 2987 | 637 | 21.3 | 411 | 13.8 |

| Twelfth | 2013 | 2987 | 699 | 23.4 | 409 | 13.7 |

Hong Kong and Macau delegations

Hong Kong has had a separate delegation since the 9th NPC in 1998, and Macau since the 10th NPC in 2003. The delegates from Hong Kong and Macau are elected via an electoral college rather than by popular vote, but do include significant political figures who are residing in the regions.[26] The electoral colleges which elect Hong Kong and Macau NPC members are largely similar in composition to the bodies which elect the chief executives of those regions. The current method of electing SAR delegations began after the handovers of sovereignty to the PRC. Between 1975 and the handovers, both Hong Kong and Macau were represented by delegations elected by the Guangdong Provincial Congress.

Taiwan delegation

The NPC has included a "Taiwan" delegation since the 4th NPC in 1975, in line with the PRC's position that Taiwan is a province of China. Prior to the 2000s, the Taiwan delegates in the NPC were mostly Taiwanese members of the Chinese Communist Party who fled Taiwan after 1947. They are now either deceased or extremely old, and in the last three Congresses, only one of the "Taiwan" delegates was actually born in Taiwan (Chen Yunying, wife of economist Justin Yifu Lin); the remainder are "second-generation Taiwan compatriots", whose parents or grandparents came from Taiwan.[27] The current NPC Taiwan delegation was elected by a "Consultative Electoral Conference" (协商选举会议) chosen at the last session of the 11th NPC.[28]

People's Liberation Army delegation

The People's Liberation Army has had a large delegation since the founding of the NPC, making up anywhere from 4 percent of the total delegates (3rd NPC), to 17 percent (4th NPC). Since the 5th NPC, it has usually held about 9 percent of the total delegate seats, and is consistently the largest delegation in the NPC. In the 12th NPC, for example, the PLA delegation has 268 members; the next largest delegation is Shandong, with 175 members.[29]

Ethnic Minorities and Overseas Chinese delegates

For the first three NPCs, there was a special delegation for returned overseas Chinese, but this was eliminated starting in the 4th NPC, and although overseas Chinese remain a recognized group in the NPC, they are now scattered among the various delegations. The PRC also recognizes 55 minority ethnic groups in China, and there is at least one delegate belonging to each of these groups in the current (12th) NPC.[30][31] These delegates frequently belong to delegations from China's autonomous regions, such as Tibet and Xinjiang, but delegates from some groups, such as the Hui people (Chinese Muslims) belong to many different delegations.

Standing Committee

A permanent organ of the NPC and elected by the NPC deputies consisting of:[32]

Structure

Special committees

In addition to the Standing Committee, nine special committees have been established under the NPC to study issues related to specific fields. These committees include:

- Ethnic Affairs Committee

- Constitution and Law Committee[33]

- Internal and Judicial Affairs Committee

- Financial and Economic Affairs Committee

- Education, Science, Culture and Public Health Committee

- Foreign Affairs Committee

- Overseas Chinese Affairs Committee

- Environment Protection and Resources Conservation Committee

- Agriculture and Rural Affairs Committee

Administrative bodies

A number of administrative bodies have also been established to provide support for the work of the NPC. These include:

- General Office

- Legislative Affairs Commission

- Budgetary Affairs Commission

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Basic Law Committee

- Macao Special Administrative Region Basic Law Committee

Presidium

The Presidium of the NPC is a 178-member body of the NPC.[34] It is composed of senior officials of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the state, non-Communist parties and All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, those without party affiliation, heads of central government agencies and people's organizations, leading members of all the 35 delegations to the NPC session including those from Hong Kong and Macao and the People's Liberation Army.[34] It nominates the President and Vice President of China, the Chairman, Vice-Chairman, and Secretary-General of the Standing Committee of the NPC, the Chairman of the Central Military Commission, and the President of the Supreme People's Court for election by the NPC.[35] Its functions are defined in the Organic Law of the NPC, but not how it is composed.[35]

Relationship with the Communist Party

The ruling Communist Party of China maintains control over the composition of people's congresses at various levels, especially the National People's Congress.[36] At the local level, there is a considerable amount of decentralization in the candidate preselection process, with room for local in-party politics and for participation by non-Communist candidates. The structure of the tiered electoral system makes it difficult for a candidate to become a member of the higher level people's assemblies without the support from politicians in the lower tier, while at the same time making it impossible for the party bureaucracy to completely control the election process.

One such mechanism is the limit on the number of candidates in proportion to the number of seats available.[37] At the national level, for example, a maximum of 110 candidates are allowed per 100 seats; at the provincial level, this ratio is 120 candidates per 100 seats. This ratio increases for each lower level of people's congresses, until the lowest level, the village level, has no limit on the number of candidates for each seat. However, the Congress website says "In an indirect election, the number of candidates should exceed the number to be elected by 20% to 50%."[38] The practice of having more candidates than seats for NPC delegate positions has become standard, and it is different from Soviet practice in which all delegates positions were selected by the Party center.[39] Although the limits on member selection allows the Party leadership to block unacceptable candidates, it also causes unpopular candidates to be removed in the electoral process. Direct and explicit challenges to the rule of the Communist Party are not tolerated, but are unlikely in any event due to the control the party center has on delegate selection.

Furthermore, the constitution of the National People's Congress provides for most of its power to be exercised on a day-to-day basis by its Standing Committee.[40] Due to its overwhelming majority in the Congress, the Communist Party has total control over the composition of the Standing Committee, thereby controlling the actions of the National People's Congress.

Although Party approval is in effect essential for membership in the NPC, approximately a third of the seats are by convention reserved for non-Communist Party members. This includes technical experts and members of the smaller allied parties.[37] While these members do provide technical expertise and a somewhat greater diversity of views, they do not function as a political opposition.[41]

See also

- Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC)

- Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC)

- Elections in the People's Republic of China

- List of voting results of the National People's Congress of China

- Politics of People's Republic of China

- National Assembly (Republic of China)

- Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union (former equivalent)

- Supreme People's Assembly

- List of legislatures by country

References

- ↑ "第十三届全国人民代表大会第一次会议主席团和秘书长名单". 4 March 2018.

- 1 2 National People's Congress of the PRC. "中华人民共和国全国人民代表大会和地方各级人民代表大会选举法(Election Law of the National People's Congress and Local People's Congress of the People 's Republic of China)". www.npc.gov.cn (in Chinese). Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ International Parliamentary Union. "IPU PARLINE Database: General Information". Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ "China Set to Make Xi Era Permanent With Sweeping Legal Overhaul". Bloomberg.com. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ "How China is ruled: National People's Congress". BBC News. 8 October 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ "What makes a rubber stamp?". The Economist. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ "China's National Party Congress will open the way to a dictatorship for President Xi Jinping". ABC News. 5 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ Riley, Charles. "China's rubber-stamp parliament: 3 things you need to know". CNNMoney. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ "Nothing to see but comfort for Xi at China's annual parliament". Reuters. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ Wee, Sui-Lee (1 March 2018). "China's Parliament Is a Growing Billionaires' Club". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ Connor, Neil (4 March 2017). "Five things to watch out for at China's National People's Congress". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ Chen, Te-Ping (5 March 2016). "At China's Rubber-Stamp Parliament, Real Stamps Are All the Rage". WSJ. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ Elegant, Simon. "The National People's Congress: Rubber Stamp?". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ "State Structure of the People's Republic of China". 中国人大网. The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ China's 'two sessions': Economics, environment and Xi's powerBBC

- ↑ "The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China". Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ↑ "How China is ruled: National People's Congress". BBC News. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ↑ Bristow, Michael, "Chinese delegate has 'no power'", BBC News, Beijing, Wednesday, 4 March 2009

- ↑ Ting, Shi (3 March 2016). "China's National People's Congress: What You Need to Know". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ↑ "Functions and Powers of the National People's Congress". The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China. The National People's Congress. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20110714024016/http://www.chathamhouse.org.uk/files/3073_npcandthesecuritieslaw.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Number of Deputies to All the Previous National People's Congresses in 2005 Statistical Yearbook, source: National Bureau of Statistics of China". Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ↑ "十一届全国人大代表将亮相:结构优化 构成广泛". Npc.people.com.cn. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ 12th Congress information from International Parliamentary Union. "IPU PARLINE Database: General Information". Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Xinhua News Agency. "New nat'l legislature sees more diversity". Npc.gov.cn. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ↑ Fu, Hualing; Choy, D. W (2007). "Of Iron or Rubber?: People's Deputies of Hong Kong to the National People's Congress". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.958845.

- ↑ Huaxia News (8 March 2012). "Taiwanese delegate Zhang Xiong: 'Stenographer' to the NPC Taiwan Delegation". Big5.huaxia.com. Retrieved 10 June 2013. (in Chinese)

- ↑ Xinhua News (9 January 2013). "Taiwan Delegates to the 12th National People's Conference Elected". News.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 10 June 2013. (in Chinese)

- ↑ National People's Congress (27 February 2013). "Delegate list for the 12th National People's Congress". Npc.gov.cn.

- ↑ Xinhua News Agency. "New nat'l legislature sees more diversity". Npc.gov.cn. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ↑ Maurer-Fazio, Margaret; Hasmath, Reza (2015). "The contemporary ethnic minority in China: An introduction". Eurasian Geography and Economics. 56: 1. doi:10.1080/15387216.2015.1059290.

- ↑ "National People's Congress Organizational System". China Internet Information Center. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ "宪法和法律委员会". www.npc.gov.cn.

- 1 2 "Presidium elected, agenda set for China's landmark parliamentary session". Xinhua News Agency. 4 March 2013. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- 1 2 林 (Lin), 峰 (Feng) (2011). 郑 (Cheng), 宇硕(Joseph Y. S.), ed. Whither China's Democracy: Democratization in China Since the Tiananmen Incident. City University of Hong Kong Press. pp. 65–99. ISBN 978-962-937-181-4. At pp. 68–69.

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/03/07/chinas-national-peoples-congress-is-meeting-this-week-dont-expect-checks-and-balances/%5Bfull+citation+needed%5D

- 1 2 http://isdp.eu/content/uploads/2017/10/China-Party-Congress-Backgrounder.pdf%5Bfull+citation+needed%5D

- ↑ "The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China". www.npc.gov.cn.

- ↑ White, Stephen (1990). "The elections to the USSR congress of people's deputies March 1989". Electoral Studies. 9: 59. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(90)90043-8.

- ↑ Saich, Tony (November 2015). "The National People's Congress: Functions and Membership". Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.

- ↑ https://qz.com/1221265/chinas-annual-communist-party-gathering-welcomes-a-handful-of-new-tech-tycoons/%5Bfull+citation+needed%5D

External links

- English

- Full coverage of the 2017 NPC & CPPCC sessions http://english.cctv.com/special/2017twosessions/

- Full coverage of the 2016 NPC & CPPCC sessions - China.org.cn

- Full coverage of the 2014 NPC & CPPCC sessions - China.org.cn

- English version of the Official website of the NPC

- NY Times article on the detainment of would-be petitioners to the NPC

- Information on National People's Congress and Standing Committee

- English version of the Standing Committee of Beijing Municipal People's Congress

- Chinese

- The official website of the NPC

- News on NPC, People's Daily Online

- Policies regarding the National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China

- The Standing Committee of Beijing Municipal People's Congress

- The official website of the Great Hall of People

Coordinates: 39°54′12″N 116°23′15″E / 39.90333°N 116.38750°E