Ethnic minorities in China

Ethnic minorities in China are the non-Han Chinese population in the People's Republic of China (PRC). China officially recognises 55 ethnic minority groups within China in addition to the Han majority.[1] As of 2010, the combined population of officially recognised minority groups comprised 8.49% of the population of mainland China.[2] In addition to these officially recognised ethnic minority groups, there are PRC nationals who privately classify themselves as members of unrecognised ethnic groups (such as Jewish, Tuvan, Oirat and Ili Turki).

The ethnic minority groups officially recognized by the PRC reside within mainland China and Taiwan, whose minorities are called the Taiwanese aborigines. The Republic of China (ROC) in Taiwan officially recognises 14 Taiwanese aborigine groups, while the PRC classifies them all under a single ethnic minority group, the Gaoshan. Hong Kong and Macau do not use this ethnic classification system, and figures by the PRC government do not include the two territories.

By definition, these ethnic minority groups, together with the Han majority, make up the greater Chinese nationality known as Zhonghua Minzu. Chinese minorities alone are referred to as "Shaoshu Minzu".

Naming

The Chinese-language term for ethnic minority is shaoshu minzu (simplified Chinese: 少数民族; traditional Chinese: 少數民族; pinyin: shǎoshù mínzú; literally: "minority nationality"). In early PRC documents, such as the 1982 constitution,[3] the word "minzu" was translated as "nationality", following the Soviet Union's use of Marxist-Leninist jargon. However, the Chinese word does not imply that ethnic minorities in China are not Chinese citizens, as in fact they are.[4] Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, governmental and scholarly publications have retranslated "minzu" in the ethnic minority sense into English as "ethnic groups". Some scholars, to be even more precise, use the neologism zuqun (Chinese: 族群; pinyin: zǔqún) to unambiguously refer to ethnicity when "minzu" is needed to refer to nationality.[5]

History of ethnicity in China

Early history

Throughout much of recorded Chinese history, there was little attempt by Chinese authors to separate the concepts of nationality, culture, and ethnicity.[7] Those outside of the reach of imperial control and dominant patterns of Chinese culture were thought of as separate groups of people regardless of whether they would today be considered as a separate ethnicity. The self-conceptualization of Han largely revolved around this center-periphery cultural divide. Thus, the process of Sinicization throughout history had as much to do with the spreading of imperial rule and culture as it did with actual ethnic migration.

This understanding persisted (with some change in the Qing under the import of Western ideas) up until the Communists took power in 1949. Their understanding of minorities had been heavily influenced by the Soviet models of Joseph Stalin—as has been the case for the neighbouring Communist regimes of Vietnam and Laos[8]—and the Soviet's definition of minorities did not map cleanly onto this Chinese historical understanding. Stalinist thinking about minorities was that a nation was made up of those with a common language, historical culture, and territory. Each nation of these people then had the theoretical right to secede from a proposed federated government.[9] This differed from the previous way of thinking mainly in that instead of defining all those under imperial rule as Chinese, the nation (as defined as a space upon which power is projected) and ethnicity (the identity of the governed) were now separate; being under central rule no longer automatically meant being defined as Chinese. The Stalinist model as applied to China gave rise to the autonomous regions in China; these areas were thought to be their own nations that had theoretical autonomy from the central government.[10]

During World War II, the American Asiatic Association published an entry in the text "Asia: journal of the American Asiatic Association, Volume 40", concerning the problem of whether Chinese Muslims were Chinese or a separate "ethnic minority", and the factors which lead to either classification. It tackled the question of why Muslims who were Chinese were considered a different race from other Chinese, and the separate question of whether all Muslims in China were united into one race. The first problem was posed with a comparison to Chinese Buddhists, who were not considered a separate race.[11] It concluded that the reason Chinese Muslims were considered separate was because of different factors like religion, culture, military feudalism, and that considering them a "racial minority" was wrong. It also came to the conclusion that the Japanese military spokesman was the only person who was propagating the false assertion that Chinese Muslims had "racial unity", which was disproven by the fact that Muslims in China were composed of multitudes of different races, separate from each other as were the "Germans and English", such as the Mongol Hui of Hezhou, Salar Hui of Qinghai, Chan Tou Hui of Turkistan, and then Chinese Muslims. The Japanese were trying to spread the lie that Chinese Muslims were one race, in order to propagate the claim that they should be separated from China into an "independent political organization".[12]

Distinguishing nationalities in the People's Republic of China

To determine how many of these nations existed within China after the revolution of 1949, a team of social scientists was assembled to enumerate the various ethnic nations. The problem that they immediately ran into was that there were many areas of China in which villages in one valley considered themselves to have a separate identity and culture from those one valley over.[13] According each village the status of nation would be absurd and would lead to the nonsensical result of filling the National People's Congress with delegates all representing individual villages. In response, the social scientists attempted to construct coherent groupings of minorities using language as the main criterion for differentiation. This led to a result in which villages that had very different cultural practices and histories were lumped under the same ethnic name. The Zhuang is one such example; the ethnic group largely served as a catch-all collection of various hill villages in Guangxi province.[14]

The actual census taking of who was and was not a minority further eroded the neat differentiating lines the social scientists had drawn up. Individual ethnic status was often awarded based on family tree histories. If one had a father (or mother, for ethnic groups that were considered matrilineal) that had a surname considered to belong to a particular ethnic group, then one was awarded the coveted minority status. This had the result that villages that had previously thought of themselves as homogenous and essentially Han were now divided between those with ethnic identity and those without.[15]

The team of social scientists that assembled the list of all the ethnic groups also described what they considered to be the key differentiating attributes between each group, including dress, music, and language. The center then used this list of attributes to select representatives of each group to perform on television and radio in an attempt to reinforce the government's narrative of China as a multi-ethnic state.[16] Particularly popular were more exoticised practices of minority groups - the claim of multi-ethnicity would not look strong if the minorities performed essentially the same rituals and songs as the Han. Many of those labeled as specific minorities were thus presented with images and representations of "their people" in the media that bore no relationship to the music, clothing, and other practices they themselves enacted in their own daily lives.

Under this process, 39 ethnic groups were recognized by the first national census in 1954. This further increased to 54 by the second national census in 1964, with the Lhoba group added in 1965.[17] The last change was the addition of the Jino people in 1979, bringing the number of recognized ethnic groups to the current 56.[18]

Reform and opening up

However, as China opened up and reformed post-1979, many Han acquired enough money to begin to travel. One of the favorite travel experiences of the wealthy was visits to minority areas, to see the purportedly exotic rituals of the minority peoples.[19][20] Responding to this interest, many minority entrepreneurs, despite themselves perhaps never having grown up practicing the dances, rituals, or songs themselves, began to cater to these tourists by performing acts similar to what was on the media. In this way, the groups of people named Zhuang or other named minorities have begun to have more in common with their fellow co-ethnics, as they have adopted similar self-conceptions in response to the economic demand of consumers for their performances.

After the breakup of Yugoslavia and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, there was a shift in official conceptions of minorities in China: rather than defining them as "nationalities", they became "ethnic groups". The difference between "nationality" and "ethnicity", as Uradyn Erden-Bulag describes it, is that the former treats the minorities of China as societies with "a fully functional division of labor", history, and territory, while the latter treats minorities as a "category" and focuses on their maintenance of boundaries and their self-definition in relation to the majority group. These changes are reflected in uses of the term minzu and its translations. The official journal Minzu Tuanjie changed its English name from Nationality Unity to Ethnic Unity in 1995. Similarly, the Central University for Nationalities changed its name to Minzu University of China. Scholars began to prefer the term zuqun (族群) over minzu.[21] The Chinese model for identifying and categorizing ethnic minorities established at the founding of the PRC followed the Soviet model, drawing inspiration from Joseph Stalin's 1953 'four commons' criteria to identify ethnic groups- "(1) a distinct language; (2) a recognized indigenous homeland or common territory; (3) a common economic life; and (4) a strong sense of identity and distinctive customs, including dress, religion and foods."[22] Similarly, the CPC used virtually the same four official criteria, although these had their own nuances unique to the Chinese ethnic and cultural makeup. A good example is found in the designation of distinct languages: as Hasmath illustrates, "while there are virtually hundreds, perhaps thousands of dialects spoken across China, a minority language is not simply a dialect. It is a language with distinct grammatical and phonological differences, such as Tibetan," and furthermore twenty-one ethnic minority groups have their own writing systems.[23]

The categorization of 55 minority groups was a major step forward from denial of the existence of different ethnic groups in China which had been the policy of Sun Yet-Sen's Nationalist government that came to power in 1911, which also engaged in the common use of derogatory names to refer to minorities (a practice officially abolished in 1951).[24] However, the Communist Party's categorization was also rampantly criticized since it reduced the number of recognized ethnic groups by eightfold, and today the wei shibie menzu (literally "undistinguished ethnic groups") total more than 730,000 people.[25] These groups include Geija, Khmu, Kucong, Mang, Deng, Sherpas, Bajia, Yi and Youth (Jewish).[26]

Ethnic groups

China is officially composed of 56 ethnic groups (55 minorities plus the dominant Han). However, some of the ethnic groups as classified by the PRC government contain, within themselves, diverse groups of people. Various groups of the Miao minority, for example, speak different dialects of the Hmong–Mien languages, Tai–Kadai languages, and Chinese, and practice a variety of different cultural customs.[27] Whereas in many nations a citizen's minority status is defined by their self-identification as an ethnic minority, in China minority nationality (shaosu minzu) is fixed at birth, a practice that can be traced to the foundation of the PRC, when the Communist Party commissioned studies to categorize and delineate groups based on research teams' investigation of minorities' social history, economic life, language and religion in China's different regions.[28]

Additionally, some ethnic groups with smaller populations are classified together with another distinct ethnic group, such as the case with the Utsuls of Hainan being classified as part of the Hui minority on the basis of their shared Islamic religion, and the Chuanqing being classified as part of the Han majority.

Additionally, the degree of variation between ethnic groups is also not consistent. Many ethnic groups are described as having unique characteristics from other minority groups and from the dominant Han, but there are also some that are very similar to the Han majority group. Most Hui Chinese are indistinguishable from Han Chinese except for the fact that they practice Islam, and most Manchu are considered to be largely assimilated into dominant Han society.

China's official 55 minorities are located primarily in the south, west, and north of China. Only Tibet Autonomous Region and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region have a majority population of official minorities, while all other provinces, municipalities and regions of China have a Han majority. In Beijing itself, the Han ethnic composition makes up nearly 96% of the total population, while the ethnic minority total is 4.31%, or a population of 584,692 (as of 2008).[29]

The degree of acceptance into and integration of ethnic minorities with the mainstream community also varies widely from group to group.[30] Notably, Beijing's neighbourhoods lack defined or distinct ethnic enclaves. Before Beijing embarked on a course of rapid and unprecedented development which drastically lessened physical space available, small Tibetan enclaves existed near the Central University of Nationalities in Haidan District, as well as several Manchurian enclaves in the city's outer parts, and Muslim Uyghur communities throughout the city.[31] However, virtually all ethnic enclaves have been eliminated as high-rise residential and corporate buildings have taken over these spaces.[32] Several Tibetan temples and Islamic mosques remain, but they "often do not reflect the local demographics of the local area."[33] For this reason, the Niujie area, which at its centre features one of the oldest mosques in China (built in 966 during the Liao Dynasty and enlarged by the Qing Emperors) remarkably survives as one of the "last important historical and present-day ethnic enclaves in Beijing."[34] Furthermore, the Beijing Municipal Government has invested over RMB10 million (about US$1.25 million) towards rebuilding a mainly-Muslim residential area.[35] Despite such measures, attitudes in China towards various minorities by the Han have long been afflicted by Han chauvinism, and is often resented by minority groups. Migration has also caused friction in some minority areas, such as Tibet and Xinjiang.[36]

There is some debate whether ethnic minorities experience clear patterns of wage discrimination or economic disadvantages, such as difficulty in finding jobs. Some studies find that urban minorities perceive lower wages compared to majority Han residents, or report difficulties either finding jobs or fitting into the workplace. Other studies find little or no evidence of wage gaps.[37] Reza Hasmath and Andrew MacDonald have posited that this discrepancy is largely due to the fact that data collection has neglected to disaggregate ethnic minorities' labour market experiences, and they utilize a new dataset that only examines the experiences of ethnic minorities. They find that while ethnic minorities in aggregate do not appear to experience any wage gap, some outsider minorities, particularly Tibetans and Turkic groups, "have a 20-25 percent wage penalty controlling for covariates [and that] these findings are robust across several different specifications."[38]

Hasmath found in a 2011 study, however, that labour market data examining the job-search, hiring and promotion experiences of ethnic minority workers and jobseekers in Beijing indicates a disadvantage faced by ethnic minorities compared to the Han group. This is especially true when it comes to employment in high-wage, skilled jobs.[39] These economic disadvantages faced by minorities may be attributable to the Chinese state's retreat from provision of welfare and social services in the wake of continuing market reforms. Until the late 1980s, ethnic minorities benefited from the Communist Party's job assignment system, whereby the government guaranteed jobs to graduates from secondary school and tertiary-level education, and all employees in government departments, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were guaranteed lifelong job security regardless of ethnic background.[40] In the late 1980s and early 1990s, however, the Communist Party abandoned its job assignment system, urging individuals to create jobs for themselves and to seek jobs in the emerging private sector.[41] New types of jobs emerged, such as those offered by foreign companies operating in China, as well as part-time, temporary and seasonal employers, with their own hiring practices and preferences. This change proved challenging for ethnic minority jobseekers.[42]

One cohort of ethnic minority workers who encounter particular economic disadvantages are minority xiajang workers (ie. laid-off SOE workers who had "stepped down from their post").[43] Over 80% of ethnic minority xiagang workers are between the ages of 36 and 50. In no small part because of their distinct cultural backgrounds and values, most of them were "educated" during the Cultural Revolution. Therefore, their secondary schooling was interrupted when they were mobilized to countryside villages for 5 to 10 years, and as such, most were not highly skilled or educated, and had difficulty finding employment when they returned to cities, despite the efforts of the central government to assign them positions and re-train them in employment centres. These measures, together with attempts to hold city job fairs for xiagang jobseekers, were not very successful.[44] As Reza Hasmath illustrates, over 40 percent of workers from ethnic minorities enter labour-intensive, casual jobs in manufacturing, construction, household jobs or farming.[45] A 2000 census finds that the hotel, retail and manufacturing trades employ the greatest numbers of ethnic minorities.[46] Many of these labour-intensive jobs are "usually paid on a daily basis and offer very low job security."[47] As such, many ethnic minority xiagang workers often rely on their families for assistance.[48]

It is important to remember that the cultural practices of ethnic minorities in China vary widely, as do the perceptions the Han majority have of them. Korean ethnic minorities in Northeast China are stereotyped and also considered hard-working, the Dai (Thai) minority in southern China are exoticized and many Western minorities are considered 'fearsome.'[49] As Hasmath and MacDonald illustrate, the different portrayals of minorities has "waxed and waned over time"- in urban environments, minorities such as the Zhuang who are considered non-threatening by Han residents have integrated reasonably well into society and working life, while groups with fundamentally different cultures from the Han, such as Tibetans and Turkic groups like Uyghurs, Kazhaks, Salars, Kyrgyzs and Tajiks are still viewed with suspicion as largely unassimilable outsiders.[50]

Minorities' marginalization from the high-wage, education-intensive (HWEI) labour market occurs in spite of the fact that their overall educational attainments match or outperform those of Han residents,[51] and despite the central government's official goal of building a 'well-off,' 'equitable' and 'harmonious' society (xiaokang), which has indeed been successfully achieved in many respects.[52] This paradoxical situation- the discrepancy between minorities' education and their representation in high-earning jobs- has emerged in large part because of barriers to equitable minority prospects for high-earning positions stemming from Han stereotypes that because of their ethnicity, a prospective employee may have difficulty adjusting to a HWEI work environment.[53] This prejudice is exacerbated by a stigma of distrust among government officials against community ethnic associations that act as a forum or information point to create awareness of ethnic minority issues (eg. Muslim Association of Beijing, Tibetan Information Centre), as there is a prevailing belief in government circles that they are "there for malice."[54] For such reasons, as Hasmath (2007) notes, it is vital "that local government and ethnic community associations take a lead and not simply rest on the laurels that ethnic minority development is vastly superior in Beijing than China's Western provinces or other Chinese urban areas," adding that "the comparison should be made between Hans and ethnic minorities within the capital city."[55]

Among the pitfalls that such new initiatives for advancing ethnic minority development in the HWEI sector have to confront is the social culture of Beijing itself. Despite longstanding government efforts to integrate ethnic minorities, Beijing has a long history "of strained ethnic relations and tensions, rather than a Confucian-inspired Socialist vision of harmony in ethnic interactions."[56] In the 1990s there was a severe crackdown on Tibetan and Uyghur activities after separatist activities in Tibet and Xinjiang made their way into the streets of Beijing.[57] In February 1997, during former President Deng Xiaopeng's funeral, bus bombings "signalled Uyghur contempt for the Chinese state."[58] Tibetan community associations were banned from meeting as part of government crackdowns in the midst of the march for Tibetan sovereignty.[59] These encounters between the state and ethnic minorities have generated a legacy of mistrust and the above-mentioned stigma within government circles that ethnic associations have malicious intent. They are suspected of a host of criminal activities, from promotion of the drug trade to incitement of "rebellious activities."[60] Such is the difficult environment that the continued effort to integrate ethnic minorities has to navigate.

The success of ethnic minorities' attempts to enter the HWEI labour market also, however, depends largely on individual efforts, experiences and circumstances, and it is at the individual level where "most opportunity lies for growth in improving the ethnic minority representation in HWEI sectors."[61] Young, soon-to-be university graduates have the best chance at breaking barriers, since they are most easily able to adapt to the rapidly shifting, urban lifestyle" of Beijing.[62] This is the case especially because many have grown up in Beijing, socializing within the dominant Han culture and at the same time being attuned to their family's ethnic background and culture, even if they have not engaged in those cultural practices themselves.[63] Consequently, as Hasmath posits, with the rising population of university-educated ethnic minorities, "the next generation of ethnic minorities have a chance to rid the paradox of ethnic minority development in the city."[64]

Evidence that widespread assimilation of ethnic minorities is occurring in Beijing (particularly among the younger generation) is especially patent on examination of the Muslim population of Beijing. Many of the elderly members of these communities assert that their children do not follow or adopt the Islamic culture; that they are Beijingers who have grown up and been educated in a Han-dominated community. As Hasmath illustrates, "their female children do not wear headscarves; the males do not wear Islamic topees. Nor do they eat traditional foods, except when going to "ethic" restaurants, which are often not staffed or owned by minorities and which are becoming popular among Beijingers overall.[65] These younger groups also do not generally speak the minority languages fluently. Muslim interviewees perceive these shifts in cultural orientation as "products of education and employment systems that promote a Han-dominated culture."[66] This process of assimilation continues despite government policy documents' promotion and attempt to preserve ethnic minority rights on paper.[67]

Much of the dialog within China regarding minorities has generally portrayed minorities as being further behind the Han in progress toward modernization and modernity.[68] Minority groups are often portrayed as rustic, wild, and antiquated. As the government often portrays itself as a benefactor of the minorities, those less willing to assimilate (despite the offers of assistance) are portrayed as masculine, violent, and unreasonable. Groups that have been depicted this way include the Tibetans, Uyghurs and the Mongols.[69] Groups that have been more willing to assimilate (and accept the help of the government) are often portrayed as feminine and sexual, including the Miao, Tujia and the Dai.[70]

The Taiwanese aboriginals include more than 14 Taiwanese aboriginal groups called Gaoshanzu by the mainland Chinese government. This is a special situation for Taiwanese minorities, because indigenous Taiwanese comprise a number of different ethnic groups with somewhat different languages and cultures. By the Taiwanese government's official records, Taiwan has 22 tribes with different cultures and languages. Among these are the Amis, Atayal, Bunun, Hla’alua, Kanakanavu, Kavalan, Taiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Saisiat, Sakizaya, Seediq, Thao, Truku, Tsou, and Yami. According to the article "Taiwanese Aborigines – the Natives of Taiwan", there are about 530,000 indigenous Taiwanese, accounting for 2.3% of the population. While many indigenous Taiwanese lived in the mountains many have since migrated to the cities. Taiwanese Aboriginals also lived on the western plains. They were called Pingpu by Han settlers. They have been assimilated by them. 85% of all Taiwanese people might have some degree of aboriginal bloodline.[71]

Demographics of the ethnic minorities

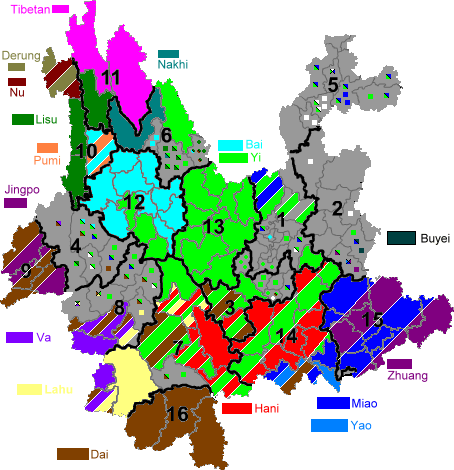

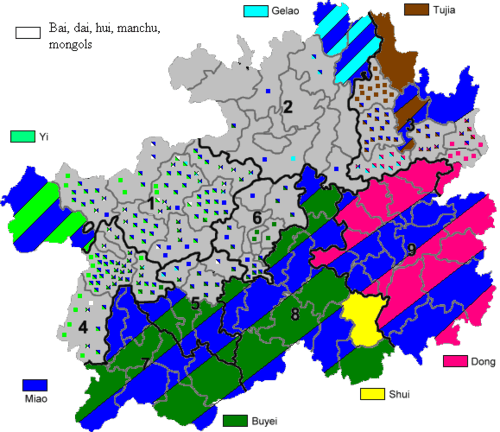

The largest ethnic group, Han, according to a 2005 sampling, constitute about 91.9% of the total population. The next largest ethnic groups in terms of population include the Zhuang (18 million), Manchu (15 million), Hui (10 million), Miao (9 million), Uyghur (8 million), Yi (7.8 million), Tujia (8 million), Mongols (5.8 million), Tibetans (5.4 million), Buyei (3 million), Yao (3.1 million), and Koreans (2.5 million). Minority populations are growing fast due to their being unaffected by the One Child Policy.[72]

Guarantee of rights and interests

The PRC's Constitution and laws guarantee equal rights to all ethnic groups in China and help promote ethnic minority groups' economic and cultural development[73] One notable preferential treatment ethnic minorities enjoy was their exemption from the population growth control of the One-Child Policy. Additionally, ethnic minorities enjoy other special exemptions which vary by province- these include lower tax thresholds and lower required scores for entry into university, as well as funding enabling them to "express their cultural difference through the arts and sports."[74] The use of these measures to raise ethnic minorities' human capital is seen by the central government as important for improving the economic development of ethnic minorities and ultimately attaining a xiaokang, or "well-off society that promotes 'equitable' and 'harmonious' stability among the ethnic minority population."[75] As Hasmath and MacDonald illustrate, universities are "expected to 'contribute to national integration and the breaking down of ethnic hatred, and to help encourage a national identity.'"[76] Ethnic minorities are represented in the National People's Congress as well as governments at the provincial and prefectural levels. Some ethnic minorities in China live in what are described as ethnic autonomous areas. These "regional autonomies" guarantee ethnic minorities the freedom to use and develop their ethnic languages, and to maintain their own cultural and social customs. In addition, the PRC government has provided preferential economic development and aid to areas where ethnic minorities live. Furthermore, the Chinese government has allowed and encouraged the involvement of ethnic minority participation in the party. Even though ethnic minorities in China are granted specific rights and freedoms, many ethnic minorities still have headed towards the urban life in order to obtain a well paid job. [77]

Minorities have widely benefited from China's minimum livelihood guarantee program (known as the dibao) a programme introduced nationwide in 1999 whose number of participants had reached nearly twenty million by 2012.[78] Reza Hasmath and Andrew MacDonald have found that minorities appear to be more likely to be enrolled in the dibao programme than the Han majority. In this programme, local officials employ a great deal of street-level discretion in selecting recipients.[79] The nature of the selection process entails that the programme's providers be proactive and willing in seeking out impoverished prospective participants, as opposed to more comprehensive welfare schemes such as the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance Scheme (URBMI), which is universally implemented. As such, the selection process for participants in the dibao programme has generated a perception among observers of the scheme that this programme and "other forms of discretionary government attention" to residents have been used to mitigate dissent and neutralize any threat to the government that could lead to unrest- including negative performance evaluations of local officials.[80] As Hasmath and MacDonald have illustrated, "the central government's discourse surrounding minorities is that they are generally poorer and needier than the average population due to their less advanced population status"- this is patently untrue[81] but appears to have led welfare providers in programmes such as the dibao to disproportionately seek out minority participants. Hasmath and MacDonald further found evidence to suggest that officials "use discretionary welfare measures to buy off potentially troublesome poorer minority households at a higher rate than Han households."[82] Conversely, minorities do not appear to encounter the same level of bias from central or local government welfare providers in more comprehensive schemes such as the URBMI, and thus are not disadvantaged as they are under the dibao scheme.[83]

Undistinguished ethnic groups

"Undistinguished" ethnic groups are ethnic groups that have not been officially recognized or classified by the central government. The group numbers more than 730,000 people, and would constitute the twentieth most populous ethnic group of China if taken as a single group. The vast majority of this group is found in Guizhou Province.

These "undistinguished ethnic groups" do not include groups that have been controversially classified into existing groups. For example, the Mosuo are officially classified as Naxi, and the Chuanqing are classified as Han Chinese, but they reject these classifications and view themselves as separate ethnic groups.

Citizens of mainland China who are of foreign origin are classified using yet another separate label: "foreigners naturalized into the Chinese citizenship" (外国人入中国籍). However, if a newly naturalized citizen already belongs to a recognized existing group among the 56 ethnic groups, then he or she is classified into that ethnic group rather than the special label.

Religions and their most common affiliations

- Buddhism/Taoism: the Miao (minority), Lisu (minority), Bai, Bulang, Dai, Jinuo, Jing, Jingpo, Mongol, Manchu, Naxi (including Mosuo), Nu, Tibetan, Zhuang (minority), Yi (minority),and Yugur ("Yellow Uyghurs").[84]

- Protestant Christianity: the Lisu (70%) - see Lisu Church

- Eastern Orthodox Christianity: the Russians

- Islam: the Hui, Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Dongxiang people, Kyrgyz people, Salar, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Bonans and Tatars.[85]

- Shamanism/Animism: Daur, Ewenkis, Oroqen, Hezhen, Derung.

See also

- Ethnic issues in China

- Affirmative action in China

- China National Ethnic Song and Dance Ensemble

- Chinese nationality law

- Sinocentrism

- Demographics of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan

- Graphic pejoratives in written Chinese

- Ethnic groups in Chinese history

- Human rights in China

- List of China administrative regions by ethnic group

- List of ethnic groups in China

- List of endangered languages in China

- Minzu University of China, a university in Beijing designated for ethnic minorities.

- Taiwanese aborigines

- Undistinguished ethnic groups in China

- Zhonghua minzu

Notes

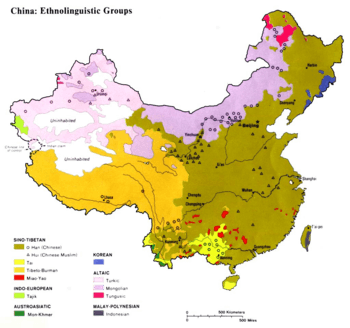

- ↑ Source: United States Central Intelligence Agency, 1983. The map shows the distribution of ethnolinguistic groups according to the historical majority ethnic groups by region. Note this is different from the current distribution due to age-long internal migration and assimilation.

References

- ↑ http://english.gov.cn/archive/china_abc/2014/08/27/content_281474983873388.htm

- ↑ http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2011-04/28/c_13849933.htm

- ↑ Constitution of the People's Republic of China Archived 23 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine., 4 December 1982. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ↑ "China's Fresh Approach to the National Minority Question," by George Moseley, The China Quarterly

- ↑ Bulag, Uradyn (2010). "Alter/native Mongolian identity". In Perry, Elizabeth; Selden, Mark. Chinese Society: Change, Conflict, and Resistance. Taylor & Francis. p. 284.

- ↑ Lee Lawrence. (3 September 2011). "A Mysterious Stranger in China". The Wall Street Journal. Accessed on 31 August 2016.

- ↑ Harrell, Stephan (1996). Cultural encounters on China's ethnic frontiers. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97380-3.

- ↑ Michaud J., 2009 Handling Mountain Minorities in China, Vietnam and Laos : From History to Current Issues. Asian Ethnicity 10(1): 25-49.

- ↑ Blaut, J. M. (1987). "The Theory of National Minorities". The National Question: Decolonizing the Theory of Nationalism. London: Zed Books. ISBN 0-86232-439-4.

- ↑ Ma, Rong (June 2010). "The Soviet Model's Influence and the Current Debate on Ethnic Relations". Global Asia.

- ↑ Hartford Seminary Foundation (1941). The Moslem World, Volumes 31-34. Hartford Seminary Foundation. p. 182. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ↑ American Asiatic Association (1940). Asia: journal of the American Asiatic Association, Volume 40. Asia Pub. Co. p. 660. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ↑ Mullaney, Thomas (2010). "Seeing for the State: The Role of Social Scientists in China's Ethnic Classification Project". Asian Ethnicity. 11 (3): 325–342. doi:10.1080/14631369.2010.510874.

- ↑ Kaup, Katherine Palmer (2002). "Regionalism versus Ethnic nationalism". The China Quarterly. 172: 863–884. doi:10.1017/s0009443902000530.

- ↑ Mullaney, Thomas (2004). "Ethnic Classification Writ Large: The 1954 Yunnan Province Ethnic Classification Project and its Foundations in Republican-Era Taxonomic Thought". China Information. 18 (2).

- ↑ Gladney, Dru C. (1994). "Representing Nationality in China: Refiguring Majority/Minority Identities". The Journal of Asian Studies. 53 (1): 92–123. doi:10.2307/2059528. JSTOR 2059528.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 467.

- ↑ List of ethnic groups in China

- ↑ Oakes, Timothy S. (1997). "Ethnic tourism in rural Guizhou: Sense of place and the commerce of authenticity". In Picard, Michel; Wood, Robert Everett. Tourism, ethnicity, and the state in Asian and Pacific societies. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-1863-6.

- ↑ Hillman, Ben (2003). "Paradise under Construction: Minorities, Myths and Modernity in Northwest Yunnan" (PDF). Asian Ethnicity. 4 (2): 177–190. doi:10.1080/14631360301654.

- ↑ Perry, Elizabeth J.; Selden, Mark; Uradyn Erden-Bulag. "Alter/native Mongolian identity: From nationality to ethnic group". Chinese Society: Change, conflict and resistance. Routledge. pp. 261&ndash, 287. ISBN 978-0-203-85631-4

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 296.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 467.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 468.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 468.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 468.

- ↑ Xiaobing Li, and Patrick Fuliang Shan, Ethnic China: Identity, Assimilation and Resistance, Lexington and Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 296.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2008). "The Big Payoff? Educational and Occupational Attainments of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". European Journal of Development Research. 20 (1): 109.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza. (2011) “From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing”, International Labour Review 150(1/2): 189-201.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2008). "The Big Payoff? Educational and Occupational Attainments of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". European Journal of Development Research. 20 (1): 110.

- ↑ Hsu, Jennifer YJ; Hildebrandt, Timothy; Hasmath, Reza (2016). "'Going Out' or Staying In? The Expansion of Chinese NGOs in Africa". Development Policy Review. 34 (3): 110.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2008). "The Big Payoff? Educational and Occupational Attainments of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". European Journal of Development Research. 20 (1): 110.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2008). "The Big Payoff? Educational and Occupational Attainments of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". European Journal of Development Research. 20 (1): 110.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2008). "The Big Payoff? Educational and Occupational Attainments of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". European Journal of Development Research. 20 (1): 110.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza. (2013) “Responses to Xinjiang Ethnic Unrest Do Not Address Underlying Causes”, South China Morning Post, 5 July.

- ↑ MacDonald, Andrew; Hasmath, Reza (2019). "Outsider Ethnic Minorities and Wage Determination in China". International Labour Review. 158: 1.

- ↑ MacDonald, Andrew; Hasmath, Reza (2019). "Outsider Ethnic Minorities and Wage Determination in China". International Labour Review. 158: 1.

- ↑ MacDonald, Andrew; Hasmath, Reza (2019). "Outsider Ethnic Minorities and Wage Determination in China". International Labour Review. 158: 189.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2011). "From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". International Labour Review. 150 (1–2): 189–190.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2011). "From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". International Labour Review. 150 (1–2): 190.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2011). "From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". International Labour Review. 150 (1–2): 191.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2011). "From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". International Labour Review. 150 (1–2): 191.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2011). "From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". International Labour Review. 150 (1–2): 191.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2011). "From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". International Labour Review. 150 (1–2): 192.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2011). "From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". International Labour Review. 150 (1–2): 193.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2011). "From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". International Labour Review. 150 (1–2): 192.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2011). "From Job Search to Hiring to Promotion: The Labour Market Experiences of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing". International Labour Review. 150 (1–2): 192.

- ↑ MacDonald, Andrew; Hasmath, Reza (2019). "Outsider Ethnic Minorities and Wage Determination in China". International Labour Review. 158: 1.

- ↑ MacDonald, Andrew; Hasmath, Reza (2019). "Outsider Ethnic Minorities and Wage Determination in China". International Labour Review. 158: 1.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 464.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 478.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 478.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 478.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 479.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 465.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 465.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 465.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 465.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 465.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 478.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 478.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 476.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 478.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 466.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 466.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2007). "The Paradox of Ethnic Minority Development in Beijing". Comparative Sociology. 6 (4): 466.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza. (2014) “The Interactions of Ethnic Minorities in Beijing Archived 16 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine.”, University of Oxford Centre on Migration, Policy and Society Working Paper 14-111: 1-26.

- ↑ Hillman, Ben (2006). "Macho Minority: Masculinity and Ethnicity on the Edge of Tibet" (PDF). Modern China. 32: 251–272. doi:10.1177/0097700405286186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2016.

Despite tremendous diversity among this broad and dubious ethnic category, the Han became the personification of the new nation and a symbol of modernity and progress. The new Communist Party leaders continued this project, presenting the Han peoples as the harbingers of modernity and progress, a beacon to the non- Han peoples of the political periphery who found themselves unwitting members of a new nation-state defined by clear borders (...) Ethnic minorities entered the national imagination as the primitive Other against which China’s modern national identity could be constructed.

- ↑ Gladney, Dru C., 1994.

- ↑ pagebao (26 July 2016). "Taiwanese Aborigines – the Natives of Taiwan". TAICHUNG.GUIDE. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ http://factsanddetails.com/china/cat5/sub29/item192.html

- ↑ http://english.people.com.cn/constitution/constitution.html

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 297.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 299.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 299.

- ↑ Yardley, Jim (11 May 2008). "China Sticking With One-Child Policy". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 302.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 312.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 303.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 306.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 313.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza; MacDonald, Andrew (2018). "Beyond Special Privileges: The Discretionary Treatment of Ethnic Minorities in China's Welfare System". Journal of Social Policy. 47 (2): 313.

- ↑ Ethnic Minorities in China

- ↑ Jackie Armijo (Winter 2006). "Islamic Education in China". Harvard Asia Quarterly. 10 (1). Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

Further reading

- Tang, Wenfang and Gaochao He. "Separate but Loyal: Ethnicity and Nationalism in China." (." () Policy Studies 56. East-West Center.

- Maurer-Fazio, M and R Hasmath (2015) "The Contemporary Ethnic Minority in China: An Introduction." Eurasian Geography and Economics 56(1): 1-7. doi:10.1080/15387216.2015.1059290

- China Ethnic Statistical Yearbook 2016

External links

- Chinese National Minorities

- The Ethnic Publishing House: on customs and autonomous places (in Simplified Chinese)

- China National Ethnic Song & Dance Ensemble

- Brief description of Chinese ethnic minority groups

- Descriptions of each ethnic minority group (china.org.cn)

- Guarantee of Rights and Interests of Ethnic Minorities

- China: Minority Exclusion, Marginalization and Rising Tensions, report by Minority Rights Group and Human Rights in China, April 2007

- Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law

- Downloadable article: "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age" Li et al. BMC Biology 2010, 8:15.