Marxism–Leninism

In political science, Marxism–Leninism is the ideology combining Marxist socioeconomic theory and Leninist political praxis, which was the official ideology of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), of the Communist International, and of Stalinist political parties.[1] The purpose of Marxism–Leninism is the revolutionary development of a capitalist state into a socialist state, effected by the leadership of a vanguard party of professional revolutionaries from the working class (the proletariat). The socialist state is realised by way of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which determines policy with democratic centralism (diversity in discussion and unity in action).[2][3]

Politically, Marxism–Leninism establishes the communist party as the primary social force to organise society as a socialist state, which is the intermediate stage of socio-economic development towards a communist society—a stateless and classless society that features common ownership of the means of production; accelerated industrialisation and concentrated development of science and technology in support of the productive forces of society;[4] and nationalisation of the land and natural resources of the country and public control of societal institutions.[5]

In the late 1920s, Joseph Stalin established ideologic orthodoxy in the Soviet Union and among the Communist International with his definition of the term "Marxism–Leninism", which redefined the theories of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin and political praxis for the exclusive benefit of the Soviet Union.[6][7] In the late 1930s, after publication of The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) (1938), Stalin’s official textbook on the subject, the term Marxism–Leninism became common, political usage among communists and non-communists.[8]

Critical of the Stalinist model of communism in the Soviet Union, the American Marxist Raya Dunayevskaya and the Italian Marxist Amadeo Bordiga dismissed Marxism–Leninism as a type of state capitalism,[9] stating that (i) Marx had identified state ownership of the means of production as a form of state capitalism—except under certain socio-economic conditions, which usually do not exist in Marxist–Leninist states;[9][10] (ii) that the Marxist dictatorship of the proletariat is a form of democracy, therefore the single-party rule of a vanguard party is undemocratic;[11] and (iii) that Marxism–Leninism is neither Marxism nor Leninism, nor a philosophic synthesis, but an artificial term that Stalin used to personally determine what is communism and what is not communism.[12]

Background

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Leninism |

|---|

|

|

Related |

|

Within five years of Vladimir Lenin's death in 1924, Joseph Stalin was the government of the Soviet Union. To justify his régime, Stalin used the book Concerning Questions of Leninism (1926), his compilation of Marx and Lenin, which presented Marxism–Leninism as a separate ideology (Stalinism)[7] which he then established as the official state ideology of the Soviet Union.[13] In governing the Soviet Union, Stalin abided and flouted the ideological principles of Lenin and Marx as expediencies to realise plans.[14]

Ideologically, the Trotskyists believe that Stalinism contradicts authentic Marxism and Leninism[15] and identified their ideology as Bolshevik–Leninism to differentiate their variety of communism from Stalin's ideology of Marxism–Leninism. Moreover, in Marxist political discourse the term "Marxism–Leninism" has two usages: (i) praise of Stalin by Stalinists (who believe Stalin successfully developed Lenin's legacy); and (ii) criticism of Stalin by Stalinists (who repudiate Stalin's repressions), such as Nikita Khrushchev and his Communist Party cohort.[16]

Consequent to the Sino-Soviet split in 1956, the communist party of each country, of the People's Republic of China and of the Soviet Union, claimed to be the sole, ideological heir-and-successor to Marxism–Leninism—and thus ideological leader of world communism.[17] In China, the official Communist China history represents Mao Zedong's practical application and adaptation of Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions as a fundamental up-dating of Leninism which is applicable worldwide—consequently, Maoism (the Thought of Mao Zedong) was the official state ideology of the People's Republic of China.[18]

In the Chinese sphere of geopolitical influence, the Sino–Albanian split (1972–1978)—caused by Albanian Communist rejection of the Chinese Communists' Realpolitik of Sino–American rapprochement (Mao and Richard Nixon meeting) as an ideological betrayal of Mao's own Three Worlds Theory—appeared as a lessening of Mao's commitment to proletarian internationalism. Among Communists, those contradictions between the orthodoxy of Maoism and Mao's pragmatism usually compelled the Marxist–Leninists to either minimise or repudiate the role of Maoism in the Communist China's actions in the International Communist Movement, wherein Mao had favoured the Party of Labour of Albania and advocated Stalinism, the stricter ideological adherence to the example of Stalin.

As revolutionary praxis, Maoism is the basic ideology of communist parties politically sympathetic to the Communist Party of China. Since the death of Mao in 1976, the Maoist Communist Party of Peru (Sendero Luminoso) coined the term Marxism–Leninism–Maoism because Maoism is the more modern Marxism, adaptable to local conditions in Third-world South America.[18] In 1977, the native Korean ideology of Juche (self-reliance) replaced Marxism–Leninism as the official state ideology of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. In contemporary socialist states, Marxism–Leninism is the official state ideology of the Republic of Cuba, the Lao People's Democratic Republic and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Marxism–Leninism in the official state ideology of the People's Republic of China as Maoism.

Marxist–Leninist state

The Marxist–Leninist state is a one-party state wherein the communist party is the political vanguard who guides the proletariat and the working classes in establishing the social, economic and cultural foundations of a socialist state, a stage of historical development enroute to a communist society.[19]

In the socialist state, government is exercised with the dictatorship of the proletariat, which defines, implements and realises policy by way of democratic centralism.[20] The administrative offices and posts of government are filled with people elected at the local, regional and national levels, usually by direct election.[21] However, indirect election also features in the Marxist–Leninist praxis of the People's Republic of China, the Republic of Cuba and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1943–1992).[21]

Economic

The goal of Marxist–Leninist political economy is the emancipation of men and women from the dehumanisation caused by mechanistic work that is psychologically alienating (without work–life balance) in exchange for wages, namely the limited financial-access to the material necessities of life (i.e. food and shelter). That emancipation from poverty (material necessity) would maximise individual liberty by enabling men and women to pursue their interests and innate talents (artistic, intellectual and so on) whilst working by choice without the economic coercion of poverty. In the communist society of upper-stage economic development, the elimination of alienating labour (mechanistic work) depends upon technological advances that improve the means of production and distribution.

To meet the material needs of society, the Marxist–Leninist state uses a planned economy to co-ordinate the means of production and of distribution to supply the goods and services required throughout society and the national economy;[22] and the worker's wages are determined according to the type of skills and the type of work he or she can perform within the national economy.[23] Moreover, the economic value of the goods and services produced is based upon their use value (as material objects) and not upon the cost of production or the exchange value.[24]

In the 1920s, the Bolshevik government's economic development realised the rapid industrialisation of Russia with pragmatic programs of social engineering that transplanted peasant populations to the cities, where they became industrial workers, who then became the workforce of the new factories and industries. Likewise, the farmer populations worked the system of collective farms to grow food to feed the industrial workers in the industrialised cities. Hence, the Marxist–Leninist society of Russia in the 1930s featured austere equality based upon asceticism, egalitarianism and self-sacrifice—yet the Bolshevik Party recognised human nature and semi-officially allowed some consumerism (limited, small-scale capitalism) to stimulate the economy of Russia.[25]

Originally, the socialist society was conceptually equal to the communist society. In defining the differences of political economy between socialism and communism, Lenin instead explained their conceptual similarity to Marx's descriptions of the lower-stage and the upper-stage of economic development; that immediately after a proletarian revolution in the lower-stage (socialist) society, the economy must be based upon the individual labour contributed by men and women; and later in the upper-stage (communist) society, the economy would be based upon requiring labour and paying wages from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.[26]

Social

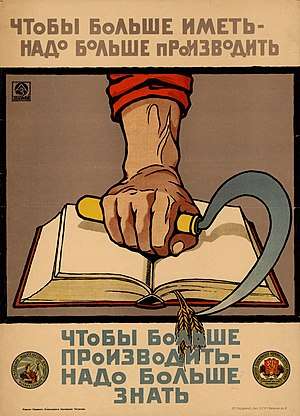

To develop a communist society, the state provides for the national welfare with universal healthcare, free public education and the social benefits necessary to increase the productivity of the workers.[27] As part of the planned economy, the welfare state is meant to develop the proletariat's education (academic and technical) and their class consciousness (political education) to facilitate their contextual understanding of the historical development of communism as presented in Marx's theory of history.[28]

The reformation of family law eliminates patriarchy from the legal system, which facilitates the emancipation of women from traditional social inferiority and economic exploitation.[29] The reformation of civil law eliminates the disproportionate political and economic powers of the bourgeoisie and voids the private property-status of the means of production. The educational system imparts the social norms for a self-disciplined and self-fulfilling way of life, by which the citizens establish the social order necessary for realizing a communist society.[30]

Cultural policy modernises social relations among the citizenry by eliminating the capitalist value system that divided people into the closed social classes of bourgeois society.[31] The cultural changes required for establishing a communist society are effected through education and agitprop (agitation and propaganda), which reinforce communal values.[32] The purpose of the educational and cultural policies of the Marxist–Leninist state is the elimination of the societal atomisation—anomie and social alienation—caused by cultural backwardness, which facilitates the development of the New Soviet man, an educated and cultured citizen possessed of a proletarian class consciousness who is oriented towards the social cohesion necessary for developing a communist society.[33]

Theological

The Marxist–Leninist world view is atheist, wherein all human activity results from human volition and not the will of supernatural beings (gods and goddesses) who have direct agency in the public and private affairs of human society.[34][35] The tenets of the Soviet Union's national policy of Marxist–Leninist atheism originated from the philosophies of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) and Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872) as well as Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924).[36]

As a basis of Marxist–Leninism, the philosophy of materialism, that the physical universe exists independently of human consciousness, applied as dialectical materialism, a philosophy of science and nature, to examine the people and things of the world in relation to each other as parts of a dynamic world unlike the metaphysical world.[37][38][39]

The Soviet physicist Vitaly Ginzburg said that the "Bolshevik communists were not merely atheists, but, according to Lenin's terminology, militant atheists" in excluding religion from the social mainstream, from education and from government.[40]

International relations

The Marxist–Leninist approach to international relations derives from the analyses (political and economic, sociological and geopolitical) that Lenin presented in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917), (1917). Parting from and developing the philosophical bases of Marxism—(i) that human history is the history of class struggle between a ruling class and an exploited class; (ii) that capitalism creates antagonistic social classes: the exploiters, the bourgeoisie; and the exploited, the proletariat; (iii) that capitalism employs nationalist war to further private economic expansion; (iv) that socialism is an economic system that voids social classes through public ownership and so will eliminate the economic causes of war; and (v) that once the state (socialist or communist) withers away, so shall international relations wither away because they are projections of national economic forces—Lenin said that the capitalists' exhaustion of domestic sources of investment profit, by way of price-fixing trusts and cartels, then prompts the same capitalists to export investment capital to undeveloped countries to finance the exploitation of natural resources and the native populations and so create new markets. That the capitalists' control of national politics ensures the government's safeguarding of colonial investments and the consequent imperial competition for economic supremacy provokes international wars to protect their national interests.[41]

In the vertical perspective (social-class relations) of Marxism–Leninism, the internal and international affairs of a country are a political continuum, not separate realms of human activity, which is the philosophic opposite of the horizontal perspectives (country-to-country) of the liberal and the realist approaches to international relations. Therefore, colonial imperialism is the inevitable consequence in the course of economic relations among countries when the domestic price-fixing of monopoly capitalism has voided profitable competition in the capitalist homeland. As such, the ideology of New Imperialism—rationalised as a civilising mission—allowed the exportation of high-profit investment capital to undeveloped countries with uneducated, native populations (sources of cheap labour), plentiful raw materials for exploitation (factors for manufacture) and a colonial market to consume the surplus production, which the capitalist homeland cannot consume; the example is the European Scramble for Africa (1881–1914), which like every imperial venture was safeguarded by the national military.[41]

To secure the colonies—foreign sources of new capital-investment-profit—the imperialist state seeks either political or military control of the limited resources (natural and human). World War I (1914–1918) resulted from such geopolitical conflicts among the empires of Europe over colonial spheres of influence.[42] For the colonised working classes who create the wealth (goods and services), the elimination of war for natural resources (access, control and exploitation) is resolved by overthrowing the militaristic capitalist state and establishing a socialist state as a peaceful world economy is feasible only by proletarian revolutions that overthrow systems of political economy based upon the exploitation of labour.[41]

History

Bolshevism

The philosophy of Marxism–Leninism originated as the pro-active, political praxis of the Bolshevik (Majority) faction, the left-wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).[43] Lenin's leadership made the Bolshevik faction the RSDLP's vanguard, i.e. committed, professional revolutionaries who elected leaders and determined policy by way of democratic centralism.[44] The Bolsheviks' pragmatic commitment to achieving revolution was their practical advantage in out-manoeuvring political parties that advocate social democracy without a plan of action, thus the Bolshevik Party successfully assumed command of the October Revolution in 1917.[44]

February Revolution

Twelve years before the October Revolution, Lenin and the Bolsheviks had failed to assume control of the February Revolution of 1905 because the centres of revolutionary action were too far apart for proper political co-ordination.[45] To generate revolutionary momentum—from Tsarist violence such as the killings on Bloody Sunday (22 January 1905)—the Bolsheviks advocated militant action, that the workers use political violence to compel the bourgeois middle classes (the nobility, the gentry and the bourgeoisie) to join the proletarian revolution to overthrow the absolute monarchy of the Tsar of Russia.[46]

Despite secret police persecution by the Okhrana (Department for Protecting the Public Security and Order), émigré Bolsheviks returned to Russia to agitate, organise and lead; and when revolutionary fervour failed in 1907, returned to exile (Lenin to Switzerland).[47] The failure of the February Revolution (1905–1907) exiled the Bolshevik (Majority) and the Mensheviks (Minority), the Socialist Revolutionaries and the anarchists from Imperial Russia—a political defeat aggravated by Tsar Nicholas II's agreement to reforming government. In practice, the formalities of the State Duma, the political plurality of a multi-party system of elections; and the Russian Constitution of 1906, were piecemeal social concessions that favoured only the aristocracy, the gentry and the bourgeoisie—but they did not resolve the malnutrition, illiteracy and poverty of the proletarian majority of Russia.[48] In Swiss exile, Lenin developed Marx's philosophy and extrapolated colonial revolt as a reinforcement of proletarian revolution in Europe.[49] Five years later in 1912, Lenin resolved a factional challenge to his ideological leadership of the RSDLP by the Forward Group in the party by usurping the all-party congress and then transformed the RSDLP into the Bolshevik Party.[50]

Great War

As promised to the Russian peoples in October 1917, Bolshevik Russia quit the Great War on 3 March 1918 unlike the European socialists who chose bellicose nationalism rather than anti-war internationalism.[51] To that effect, a small group of anti-war socialist leaders, including Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Lenin, denounced the European socialists' forsaking the solidarity of working class internationalism for patriotic war.[51] In the essay Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917), Lenin explained that capitalist expansion leads to colonial imperialism, which is regulated with wars—such as the Great War among the empires of Europe.[52][53] Late in 1917—to relieve strategic pressures from the Western Front (4 August 1914–11 November 1918)—Imperial Germany impelled Imperial Russia's withdrawal from the war's Eastern Front (17 August 1914–3 March 1918) by sending Lenin and his Bolshevik cohort in a diplomatically sealed train to realise socialist revolution in Russia.[54]

October Revolution and civil war

In March 1917, the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia led to the Russian Provisional Government (March–July 1917), who then proclaimed the Russian Republic. Three months later in the October Revolution, the Bolshevik coup d'état against the Provisional Government resulted in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (1917–1991), the first socialist state. Yet parts of Russia remained occupied by the counter-revolutionary White Movement, Tsarist and anti-communist military commanders who formed the White Army to fight the Russian Civil War (1917–1922) against the Bolshevik régime. Moreover, Russia remained a combatant in the Great War (1914–1918), which Bolshevik Russia quit with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (3 March 1918) and so provoked the Allied Intervention to the Russian Civil War (1918–1925) by the armies of seventeen countries, featuring Great Britain, France, Italy, the United States and Imperial Japan.[55]

In 1918, the Bolsheviks consolidated government power by expelling the Mensheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries from the soviets.[56] The Bolshevik government then established the Cheka secret police to eliminate anti–Bolshevik opposition in Russia. Initial opposition to the Bolshevik régime was strong for not having resolved the food shortages and poverty of the Russian peoples as promised in October 1917. From that social discontent, the Cheka reported 118 uprisings, including the Kronstadt rebellion (7–17 March 1921).[56]

- Nationalisation and War Communism

The Bolshevik government introduced limited nationalisation of the means of production, which had been private property of the Russian aristocracy during the Tsarist monarchy.[57] To fulfil the promised redistribution of Russia's arable land, Lenin encouraged the peasantry to reclaim their farmlands from the aristocrats and so ensured the peasantry's political loyalty to the Bolshevik Party.[57] In mid-1918, to overcome the civil war's economic interruption, the War Communism policy featured a regulated market, state-control of the means of distribution and the Decree on Nationalisation of large-scale farms, which requisitioned grain to feed industrial workers in the cities and the Red Army in the field, all while fighting the White Army, who was seeking to re-establish the Romanov dynasty as absolute monarchs of Russia.[57] Politically, the forced grain-requisitions discouraged peasants from farming, which resulted in reduced-harvests and food-shortages, which in turn provoked labour strikes and food riots. With the economic chaos—caused by the Bolshevik government's voiding the monetary economy—the Russian people replaced with barter and the black market.[57]

- New Economic Policy

In 1921, the New Economic Policy restored some private enterprise to animate the Russian economy. As part of Lenin's pragmatic compromise with external financial interests in 1918, Bolshevik state capitalism temporarily returned 91 per cent of industry to private ownership—until the Soviet Russians learned to operate and administrate said industries.[58][57] In that vein, Lenin explained that developing socialism in Russia would proceed according to the material and socio-economic conditions of Russia and not as described by Marx in the 19th century. Lenin's pragmatic explanation was the following: "Our poverty is so great that we cannot, at one stroke, restore full-scale factory, state, socialist production".[57] To overcome the lack of educated Russians who could operate and administrate industry, Lenin advocated the development of a technical intelligentsia who would propel the industrial development of Russia to self-sufficiency.[45]

The principal obstacles to Russian economic development and modernisation were great material poverty and the lack of modern technology, which conditions orthodox Marxism considered unfavourable to communist revolution; and that agricultural Russia was right for developing capitalism, but wrong for the development of socialism.[45] [59] The 1921–1924 period was tumultuous in Russia, with the simultaneous occurrence of economic recovery, famine (1921–1922) and a financial crisis (1924).[60] By 1924, the Bolshevik government had achieved much economic progress and by 1926 the production levels of the Soviet Union's economy had risen to the production levels registered in 1913.[60]

- Revolutionary consequences

Elsewhere, the successful October Revolution in Russia facilitated communist revolution in Imperial Germany and in Hungary during the 1918–1920 period. In Berlin, the German government and their Freikorps mercenaries fought and defeated the Spartacist uprising (4–5 January 1919), which began as a general strike; and in Munich, likewise fought and defeated the Bavarian Soviet Republic (April 1919). In Hungary, the workers proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic (March–August 1919), which was defeated by the royal armies of the Kingdom of Romania and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the army of Czechoslovakia. In Asia, successful Mongolian communist revolution established the Mongolian People's Republic (1924–1992).

Stalin assumes power

_issue_15_dated_15_Sep_1923.jpg)

- Lenin's warning

In his political testament (December 1922) to the Communist Party, Lenin ordered Stalin removed from being the party's General Secretary and replaced with "some other person who is superior to Stalin only in one respect, namely, in being more tolerant, more loyal, more polite, and more attentive to comrades".[61] At his death on 21 January 1924, Lenin's testament was read aloud to the Central Committee of the party, but enough committeemen believed in Stalin's political rehabilitation in 1923 and ignored Lenin's order to remove Stalin.[61][62]

- Power struggle

Consequent to personally spiteful disputes about the praxis of Leninism, to the October Revolution veterans, Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, the true, ideological threat to the integrity of the Communist Party was Trotsky—a personally charismatic political-leader; the commanding officer of the Red Army in the civil war; and revolutionary partner of the dead Lenin.[62] To thwart Trotsky's likely election to head the Communist Party, Stalin, Kamenev and Zinoviev formed a Troika (Triumvirate), wherein Stalin was General Secretary of the Communist Party—the de facto centre of power in the party and the country.[63]

The direction of the Communist Party was decided in the confrontation of politics and personality—between Stalin's Troika and Trotsky—over which Marxist policy to pursue, namely Trotsky's policy of permanent revolution or Stalin's policy of socialism in one country. Permanent revolution featured rapid industrialisation of the economy, the collectivisation of private farmlands and the Soviet Union's promotion of worldwide communist revolution.[64] Socialism in one country featured moderate-pace national development and the establishment of economic and diplomatic relations with other countries in order to increase international trade with and foreign investment in the Soviet Union.[63]

To politically isolate and oust Trotsky from the party, Stalin expediently advocated the politics of socialism in one country—to which he was indifferent.[64] In 1925, the 14th Communist Party Congress approved Stalin's policy and Trotsky was politically defeated as a possible rival leader of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union.[64]

In the 1925–1927 period, Stalin dissolved the Troika and disowned the moderate Kamenev and Zinoviev for an expedient alliance with the equally opportunistic Nikolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov (Premier of Russia, 1924–1929; Premier of the Soviet Union, 1924–1930)[65] and Mikhail Tomsky (leader of the All-Russian Central Council of Trade Unions)—the most right-wing Revolution-era Bolsheviks in the party.[64] The 1927 Communist Party Conference endorsed Stalin's socialism in one country as the national policy for the Soviet Union and expelled Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev from the party's Politburo.[64]

- Power consolidated

In 1929, Stalin had assumed control (personal and political) of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union proper by way of deception and administrative acumen.[64] By then, the Stalinist régime of socialism in one country had associated revolutionary Bolshevism with the harsh socio-economic policies that a centralised state required to realise the rapid industrialisation of the cities and the collectivisation of agriculture in Russia as well as to subordinate the national interests of the world's communist parties to the geopolitical interests of the Soviet Communist Party.[44]

In the 1929–1932 period of the first five-year plan, Stalin effected the dekulakization of Russian farmlands, a politically radical and harsh dispossession of the kulak class of peasant-landlords, about which Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky had moderate-action recommendations to ameliorate the policy. Stalin took umbrage and accused them of un-communist betrayals of Marxism and Leninism.[64] From that implicit accusation of ideological deviation, Stalin then accused the three October Revolution veterans of plotting against the party and compelled their resignations from public office and from their posts in the Politburo.[64]

To complete his purge of the Communist Party, Stalin then exiled Trotsky from the Soviet Union in 1929.[64] From 1929 onwards, internal opposition to Stalin's régime created Trotskyism (Bolshevik–Leninism), which was outlawed as ideological deviance from Marxism–Leninism, the state ideology of the Soviet Union.[44]

- Power legalised

In the 1929–1941 period, Stalin's elimination of Bolshevik rivals ended democracy in the Communist Party and replaced them with his personal control of the party's institutions.[66] The ranks and files of the Communist Party increased with members from the trade unions and from the factories, whom he controlled because there were no other Bolsheviks to contradict Stalin's version of Marxism–Leninism.[66] In 1936, the Soviet Union adopted a new, political constitution which ended weighted-voting preferences for workers and promulgated universal suffrage for every man and woman older than 18 years of age; and organised the soviets (councils of workers) into two legislatures (Supreme Soviet): (i) the Soviet of the Union (representing electoral districts); and (ii) the Soviet of Nationalities (representing the ethnic groups of the country); and by 1939 he had either killed or expelled from the Communist Party all of the Bolsheviks from the October Revolution era.[66]

- Dictator of the Soviet Union

Under guise of governing by the principles of Marxism–Leninism, Stalin's dictatorial régime made the Soviet Union a police state unlike Lenin's socialist state of the Bolshevik period.[67] Extensive personal control over the men who were the Communist Party licensed Stalin to use political violence to eliminate anyone who might be a threat—real, potential, or imagined.[67]

As an administrator, Stalin governed the Soviet Union by controlling the formulation of national policy and delegated implementation to subordinate Communist Party functionaries. Such freedom of action allowed local communist functionaries much discretion to interpret the intent of orders from Moscow, which allowed their corruption.[67] To Stalin, the correction of such abuses of authority and economic corruption were responsibility of the secret police, the NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs).[67] With the Great Purge (1936–1938), Stalin rid himself of internal enemies in the party and rid Russia of every counter-revolutionary, reactionary and socially dangerous man and woman who might offer legitimate political opposition to Marxism–Leninism. In the 1937–1938 period, the NKVD arrested 1.5 million people from every stratum of the Communist Party and of soviet society and killed 681,692 people for political reasons.[68] To provide manpower (intellectual and manual) to realise the construction projects for Stalin's rapid industrialisation of Russia, the NKVD established the Gulag system of forced-labour camps for criminal convicts and political dissidents, for artists and intellectuals, for homosexual people and religious anti-communists.[66]

Socialism in one country (1929–1941)

- Rapid industrialisation

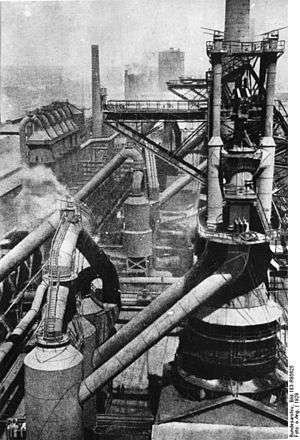

Five-year plans for the national economy of the Soviet Union achieved the rapid industrialisation (coal, iron and steel, electricity, petroleum and so on) and the collectivisation of agriculture[69]—achieving 23.6% collectivisation within one year (1930) and 98% collectivisation within twelve years (1941).[70] In the 1920s—the time of the Russian Civil War (1917–1922) and the seventeen foreign armies of the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War (1918–1925)—as the revolutionary vanguard of the nation the Communist Party had organised Russian society to realise the rapid industrialisation programs as defence against Western interference with Bolshevik Russia.[71]

Rapid industrialisation accelerated the Russians' sociological transition from the poverty of Tsarist serfdom to the relative plenty of Communist self-determination as peasants became urban citizens.[72] During the 1930s, the Marxist–Leninist economic régime modernised Russia from an illiterate, peasant society under Tsarist monarchy to a literate society of farmers and industrial workers under socialism. Unemployment was almost nil.[72]

- Social engineering

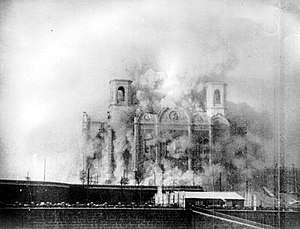

In 1934, Stalin's development of Soviet society contradicted and then replaced, the social, cultural and intellectual freedoms of Lenin's Bolshevik period. In education, traditional Russian authoritarianism (harsh discipline, school uniforms and so on) replaced pedagogic experimentation and relaxed social conduct; mental conformity, rather than intellectual liberty.[73] Culturally, the Russian arts were subordinated to the ideological limitations of socialist realism, a form of Russian patriarchy admired by the traditionalist Stalin.[73] Organised religion was excluded from the political mainstream of Soviet society and was repressed whenever a religious organisation openly opposed the official atheism of the Soviet Union.[73]

- International relations

In 1933, the Marxist–Leninist geopolitical perspective was that the Soviet Union was surrounded by capitalist and anti-communist enemies, for which reason the election of Adolf Hitler and the concomitant Nazi Party government in Germany initially resulted in the Soviet Union severing political and diplomatic relations established in the 1920s. In 1938, Stalin turned to accommodate Czechoslovakia and the West in defence against Hitler's threat of pre-emptive warfare to "recover" the Sudetenland, the German peoples and lands within Czecho.[74]

To challenge Nazi Germany's bid for European supremacy and hegemony, Stalin promoted anti-fascist fronts throughout Europe with socialists, democrats and so on and entered political agreements with France to counter Nazi Germany in the west of Europe.[74] After the Nazis bluffed the British into the Munich Agreement (29 September 1938) that allowed the German occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–1945), Stalin reversed his anti-German foreign policy and adopted pro-German policies.[74] In 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany agreed to both a Treaty of Non-aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, 23 August 1939) and agreed to jointly invade and partition Poland by which Nazi Germany started World War II on 1 September 1939.[75]

_(B%26W).jpg)

Great Patriotic War (1941–1945)

In the 1941–1942 period of the Great Patriotic War, the German invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa, 22 June 1941) was ineffectively opposed by the Red Army, who were poorly led, ill-trained and under-equipped and so fought poorly and suffered great losses of dead and wounded and prisoners of war. Such Soviet military weakness was one consequence of the Great Purge of senior officers and career soldiers.[76] The extensive and greatly effective Nazi attack threatened the territorial integrity of the Soviet Union and the political integrity of Stalin's Marxist–Leninist state because the Nazis were initially welcomed as liberators by nationalist, anti-communist and anti-Soviet populations in the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The nationalists' collaboration with the anti-communist Nazi occupier lasted until the SS and the Einsatzgruppen began their Lebensraum killings, i.e. the genocide of the Jewish communities and the systematic extermination of communists and civil leaders to realise the ethnic cleansing of Soviet lands for German colonisation. In response, Stalin ordered the Red Army to fight campaigns of total war against the exterminating invaders of Russia. Hitler's attack against his erstwhile Communist ally, realigned Stalin's policies and priorities from the repression of internal enemies to the existential defence of Russia against an external enemy, namely the aggressively anti-Communist Third Reich. The Nazi attack compelled Stalin to a pragmatic alliance with the Western Powers in common front against the Axis Powers—Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan.

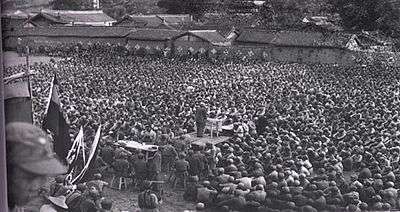

Elsewhere in the countries invaded by the Axis powers, the native communist party usually led armed resistance (guerrilla warfare and urban guerrilla warfare) against military occupation. In Asia, Stalin ordered the Communist Party of China, led by Mao Zedong, to abandon the Chinese Civil War (1937–1941) and collaborate with the anti-communist Kuomintang as the Second United Front in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), the occupation of China. In Mediterranian Europe, the Communist Yugoslav Partisans, led by Josip Broz Tito, effectively resisted the Nazi and Fascist occupation. In the 1943–1944 period, Tito's Partisans liberated territories with Red Army assistance and established the Communist political authority that became the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

- Communist victory

In 1943, the Red Army began to repel the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, especially at the five-month Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 1942–2 February 1943) and at the eleven-day Battle of Kursk (5–16 April 1943); and afterwards repelled the Nazi and Fascist occupation armies from Russia and the countries of Eastern Europe until decisive defeat in Germany proper, with the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation (16 April–2 May 1945).[77] On concluding the Great Patriotic War (1941–1945), the Soviet Union was a military superpower who had a say in the geopolitical order of the world.[77] In that vein and in accordance with the three-power Yalta Agreement (4–11 February 1945), the Soviet Union purged native Fascist collaborators from the Eastern European countries occupied by the Axis Powers and afterwards installed native Communist governments to establish a geographic buffer-zone of satellite states to protect the borders of Russia.

Cold War (1945–1991)

At the end of World War II (1939–1945), geopolitical tensions among the non-Communist Western Allies and the Communist Eastern allies resulted in the Cold War (1945–1991) between the blocs led by the United States and the Soviet Union. The events that precipitated the Cold War were the Soviet and Yugoslav, Bulgarian and Albanian intervention to the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) in behalf of the Greek Communists and the Soviet Unions's Berlin Blockade (1948–1949). In China, the civil war resumed between the Western-backed anti-communist Kuomintang, led by Chiang Kai-shek, against the Soviet-backed Chinese Communist Party led by Mao Zedong. When the Communists defeated the Kuomintang, Mao established the People's Republic of China on 1 October 1949.

In 1950, the Korean civil war became the Korean War (1950–1953), the first East–West war occurred in Asia during the Cold War. In response to invasion from North Korea, the United Nations Security Council, with the Soviet Union absent for the vote, decided on international intervention to cease the warfare in Korea. The United States and their Western European allies used the war to support South Korea, led by Syngman Rhee, against Soviet- and Chinese-backed North Korea, led by Kim Il-sung. In 1953, an armistice halted the Korean War in stalemate.

De-Stalinization

Among the European communist countries, the Yugoslav–Soviet split (1948) resulted from Tito's rejection of Stalin's demand that Yugoslav national goals be subordinated to the Soviet Union's geopolitical agenda (ideological, political, economic). After denouncing Tito as a bad communist and Yugoslavia as disloyal to the international communist cause, Stalin expelled Yugoslavia from the Cominform, the Communist Information Bureau. Having rejected Soviet hegemony through membership in the Eastern Bloc, Tito developed Titoism, the Yugoslav variety of Marxism–Leninism that is a nationalist road to socialism unlike that of the Soviet Union; and then sought and established Yugoslavia's relations with the East and the West, which then developed into the Non-Aligned Movement (1961).

At the death of Stalin in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev became leader of the Communist Party and of the Soviet Union. Three years later at a Communist Party congress in the speech On the Cult of Personality and its Consequences (25 February 1956), Khruschev secretly announced the de-Stalinisation of the Communist Party and of the Soviet Union; condemned Stalin's dictatorial excesses; ordered the dismantling of the Gulag forced-labour camps; and allowed a measure of freedom of expression to political activists, such as the novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, but did not personally criticise the dead Stalin. Khrushchev's de-Stalinization ended Stalin's policies of socialism in one country and re-committed the Soviet Union to actively supporting perpetual revolution. In that vein, the Khruschev government promoted the policies of de-Stalinization as the restoration of Leninism as the official state ideology of the Soviet Union.[78]

Maoism

In the 1960s, the People's Republic of China developed Maoism (the Mao Zedong Thought) as a Chinese variant of Marxism–Leninism which later provoked ideological, political and nationalist tensions between the Soviet Union and China about the correct orthodox-interpretation of Marxist–Leninist ideology. Given the different stages of Russian and Chinese development, the Communists' intractable ideological arguments provoked the Sino-Soviet split (1956–1966).[17]

Afterwards, China pursued détente with the United States as a challenge to the Soviet Union for the leadership of the international communist movement. China's pragmatic overture permitted geopolitical rapprochement and facilitated President Nixon's 1972 visit to China, which subsequently ended the American policy of "two Chinas" when the United States sponsored the People's Republic of China to replace the Republic of China (Taiwan) to representing the Chinese people at the United Nations. The People's Republic of China then took a seat in the Security Council.

In the post-Mao period, Deng Xiaoping (1982–1987) effected policies of economic liberalisation which resulted in continual economic growth for the country. The ideological justification is socialism with Chinese characteristics, the adaption of Russian Marxism–Leninism to China.

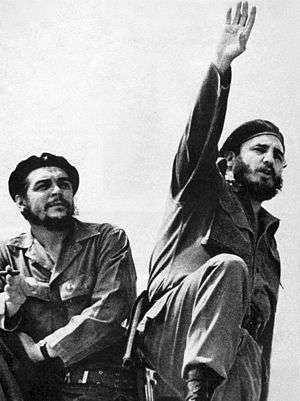

Marxist–Leninist revolution

In Latin America, Communist revolutions based upon Marxism–Leninism occurred in Bolivia, Cuba, El Salvador, Grenada, Nicaragua, Peru and Uruguay. In 1959, the Cuban Revolution, led by Fidel Castro and Ché Guevara, overthrew the régime (1925–1959) of Fulgencio Batista to establish the Republic of Cuba, a Communist state recognised by the Soviet Union. In response, the United States attempted a coup d'état against the Castro government, such as the unsuccessful Bay of Pigs invasion (April 1961), by anti-communist Cuban exiles, sponsored by the CIA. The next year, there occurred the Cuban missile crisis (October 1962), a diplomatic dispute between the United States and the Soviet Union over the presence of medium-range, Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. The Soviet Union resolved the nuclear-missile crisis by removing their missiles from Cuba in exchange for the United States removing their nuclear missiles from the Turkey–Soviet Union border. In Bolivia, the Communist revolution included Guevara until his execution by the Bolivian Army. In Uruguay, the Tupamaros movement was active from the 1960s to the 1970s.

In 1970, there occurred the October Crisis in Canada, a brief revolution in the province of Quebec, where the separatist Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped James Cross, the British Trade Commissioner in Canada; and Pierre Laporte, the Quebec government minister, who was killed. The FLQ's manifesto condemned English-Canadian imperialism in French Québec and called for a Québecois socialist state. The harsh Canadian government response included suspension of civil liberties in Quebec, which compelled the FLQ leaders' flight to Cuba.

In 1979, Daniel Ortega, leader of the Sandinista National Liberation Front, became head of state of Nicaragua upon winning the Nicaraguan civil war. Within months, the United States government of Ronald Reagan then sponsored the Contras in a secret war (1979–1990) against Nicaragua. In 1983, the United States invasion of Grenada impeded the assumption of power by the New Jewel Movement (1973–1983), a vanguard party led by Maurice Bishop. The Salvadoran Civil War (1979–1992) featured the popularly supported Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, an organisation of left-wing parties fighting against the right-wing military government of El Salvador.

The Vietnam War (1945–1975) was the second East–West war that occurred in Asia during the Cold War. After the Vietnamese Communists led by Ho Chi Minh defeated the French re-establishment of European colonialism in Viet Nam, the United States replaced France as the Western support of the client-state Republic of Vietnam (1955–1975). Despite military superiority, the United States failed to safeguard South Vietnam from the Viet Cong, the guerrilla army sponsored by North Vietnam. In 1968, North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive. Although a military failure, the attack was successful psychological warfare that decisively turned international public opinion against the United States intervention to the Vietnamese civil war and five years later eventual United States withdrawal from the war in 1973 and the subsequent Fall of Saigon to the Vietnamese Communists forces in 1975.

Consequent to the Cambodian Civil War and in coalition with Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the native Cambodian Communists, the Maoist Khmer Rouge (1951–1999) led by Pol Pot, established Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1982), a Marxist–Leninist state that featured class warfare to restructure the society of old Cambodia; to be effected and realised with the abolishment of money and private property, the outlawing of religion, the killing of the intelligentsia and compulsory manual labour for the middle classes by way of death-squad state terrorism.[79]

To eliminate Western cultural influence, Kampuchea expelled all foreigners and effected the destruction of the urban bourgeoisie of old Cambodia, first by displacing the population of the capital city (Phnom Penh); and then by displacing the entire national populace to work the farmlands to increase food supplies. Meanwhile, the Khmer Rouge purged Kampuchea of internal enemies (social class and political, cultural and ethnic) at the killing fields, the scope of which became crimes against humanity that destroyed 2, 700, 000 people by mass murder and genocide.[80][81] That social restructuring of Cambodia included attacks against the Vietnamese ethnic minority in Kampuchea, which aggravated the historical, ethnic rivalries between the Viet and the Khmer peoples. Beginning in September 1977, Kampuchea and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam continually engaged in border clashes. In 1978, Vietnam invaded Kampuchea and captured Phnom Penh in January 1979, deposed the Maoist Khmer Rouge from government and established the Cambodian Liberation Front for National Renewal as the government of Cambodia.[81]

In the 1968–1980 period in Africa, Angola, Benin, the Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Somalia and Zimbabwe became Marxist–Leninist states governed by their respective native peoples; Marxist–Leninist guerrillas fought the Portuguese Colonial War in three countries, Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique; overthrew of the monarchy of Haile Selassie and established the Derg government (1974–1987) of the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police and Territorial Army in Ethiopia; Robert Mugabe led the successful civil war to overthrow white-minority rule in Rhodesia (1965–1979) in order to establish Zimbabwe. In South Africa, the anti-communist, white-minority government—based upon the official racism of apartheid—caused much geopolitical tension between the Soviet Union and the United States. In 1976, anti-communism became morally untenable for the West when the South African government killed 176 people (students and adults) in the suppression of the Soweto uprising (June 1976), which protested Afrikaner cultural imperialism, the racist imposition of Afrikaans (a European Germanic language) as the language for teaching school and as the language that black South Africans must speak to white people; and the police assassination in September 1977 of Steven Biko, a leader of the internal resistance to apartheid in South Africa.[82]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Dictionary of Historical Term (1998) Second Edition, Chris Cook, Ed., pp. 221–222, p. 305.

- ↑ Dictionary of Historical Terms (1998) Second Edition, Chris Cook, Ed., pp. 221–222.

- ↑ Albert, Michael; Hahnel, Robin. Socialism Today and Tomorrow. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: South End Press, 1981. pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Andrain, Charles F. Comparative Political Systems: Policy Performance and Social Change. Armonk, New York, USA: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1994. p. 140.

- ↑ Todd, Allan. History for the IB Diploma: Communism in Crisis: 1976–89, p. 16. "The term Marxism–Leninism, invented by Stalin, was not used until after Lenin's death in 1924. It soon came to be used in Stalin's Soviet Union to refer to what he described as 'orthodox Marxism'. This increasingly came to mean what Stalin, himself, had to say about political and economic issues. . . . However, many Marxists (even members of the Communist Party, itself) believed that Stalin's ideas and practices (such as socialism in one country and the purges) were almost total distortions of what Marx and Lenin had said".

- ↑ Bullock, Allan, Trombley, Stephan. Eds. The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (1999) Third Edition, p. 506.

- 1 2 Lisischkin, G. (Г. Лисичкин), Novy Mir (Мифы и реальность, Новый мир), 1989, № 3, p. 59 (in Russian).

- ↑ "Marxism" entry in the Soviet Encyclopedic Dictionary.

- 1 2 Howard, M.C., King, J.E. "State capitalism" in the Soviet Union".

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Nelson. "American Capitalism: Social Thought and Political Economy in the Twentieth Century" (2011) University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 160–161

- ↑ Ishay, Micheline. The Human Rights Reader: Major Political Essays, Speeches, and Documents from Ancient Times to the Present (2007) Taylor & Francis. p. 245.

- ↑ Todd, Allan. History for the IB Diploma: Communism in Crisis 1976–89, p. 16.

- ↑ Александр Бутенко (Aleksandr Butenko), Социализм сегодня: опыт и новая теория// Журнал Альтернативы, №1, 1996, pp. 3–4 (in Russian).

- ↑ Александр Бутенко (Aleksandr Butenko), Социализм сегодня: опыт и новая теория// Журнал Альтернативы, №1, 1996, pp. 2–22 (in Russian)

- ↑ Лев Троцкий (Lev Trotsky), Сталинская школа фальсификаций, М. 1990, pp. 7–8 (in Russian)

- ↑ М. Б. Митин (M. B. Mitin). Марксизм-ленинизм (in Russian). Яндекс. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- 1 2 Chambers Dictionary of World History, B.P. Lenman, T. Anderson editors, Chambers: Edinburgh: 2000. p. 769.

- 1 2 The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, Third Edition (1999), Allan Bullock and Stephen Trombley, Eds., p. 501.

- ↑ Shtromas, Alexander, Faulkner, Robert K, Mahoney, Daniel J. Totalitarianism and the Prospects for World Order: Closing the Door on the Twentieth Century (2003). Lexington Books. p. 18.

- ↑ Albert, Michael and Hahnel, Robin. Socialism Today and Tomorrow (1981) Boston, Massachusetts, USA: South End Press, pp. 24–25.

- 1 2 Pons, p. 306.

- ↑ Pons, p. 138.

- ↑ Pons, p. 140.

- ↑ Pons, p. 139.

- ↑ Pons, p. 732.

- ↑ The Oxford Companion to Comparative Politics (2012), Joel Krieger and Craig N. Murphy, Eds. Oxford University Press, p. 218.

- ↑ A Dictionary of 20th-Century Communism (2010), Silvio Pons, p. 721–723.

- ↑ Pons, p. 580.

- ↑ Pons, pp. 854–856.

- ↑ Pons, p. 319.

- ↑ Pons, p. 250.

- ↑ Pons, pp. 250–251.

- ↑ Pons, p. 581.

- ↑ Thrower, James. Marxism–Leninism as the Civil Religion of Soviet Society E. Mellen Press, 1992. p. 45.

- ↑ Kundan, Kumar. Ideology and Political System (2003) Discovery Publishing House, 2003. p. 90.

- ↑ Slovak Studies, Volume 21. The Slovak Institute in North America. p. 231. "The origin of Marxist–Leninist atheism, as understood in the USSR, is linked with the development of the German philosophy of Hegel and Feuerbach."

- ↑ "Materialistisk dialektik".

- ↑ Jordan, Z. A.The Evolution of Dialectical Materialism (1967).

- ↑ Paul Thomas, Marxism and Scientific Socialism: From Engels to Althusser (London: Routledge, 2008).

- ↑ Ginzburg, Vitalij Lazarevič, On Superconductivity and Superfluidity: A Scientific Autobiography (2009) p. 45.

- 1 2 3 Penguin Dictionary of International Relations (1998), Graham Evans and Jeffrey Newnham, Eds. pp. 316–317.

- ↑ Dictionary of Historical terms (1998), Chris Cook, Ed., p. 221.

- ↑ Bottomore, pp. 53–54.

- 1 2 3 4 Bottomore, p. 54.

- 1 2 3 Bottomore, p. 259.

- ↑ Ulam, p. 204.

- ↑ Ulam, p. 207.

- ↑ Ulam, p. 269.

- ↑ Bottomore, p. 98.

- ↑ Ulam, pp. 282–83.

- 1 2 Anderson, Kevin. Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism: A Critical Study (1995) Chicago, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press, p. 3.

- ↑ Penguin Dictionary of International Relations (1998), Graham Evans and Jeffrey Newnham, Eds., p. 317.

- ↑ Cavanagh Hodge, Carl. Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800–1914, Volume 2 (2008) Westport, Conn., USA: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. p. 415.

- ↑ Beckett, Ian Frederick William. 1917: beyond the Western Front (2009) Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV. p. 1.

- ↑ Lee, p. 31.

- 1 2 Lee, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lee, p. 38.

- ↑ Dictionary of Historical Terms Second Edition (1998), Chris Cook, Ed., p. 306.

- ↑ Ulam, p. 249.

- 1 2 Lee, p. 39.

- 1 2 Lee, p. 41.

- 1 2 Lee, pp. 41–42.

- 1 2 Lee, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lee, p. 43.

- ↑ "Aleksey Ivanovich Rykov biography —Archontology".

- 1 2 3 4 Lee, p. 49.

- 1 2 3 4 Lee, p. 47.

- ↑ Pons, p. 447.

- ↑ Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914–1991 (1996), pp. 380–81

- ↑ Lee, p. 60.

- ↑ Lee, p. 59.

- 1 2 Lee, p. 62.

- 1 2 3 Lee, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 Lee, p. 74.

- ↑ Lee, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Lee, p. 80.

- 1 2 Lee, p. 81.

- ↑ The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991, by Ronald E. Powaski. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- ↑ The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern THought Third Edition (1999), Allan Bullock and Stephen Trombley, Eds., p. 458.

- ↑ The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought Third Edition (1999), Allan Bullock and Stephen Trombley, Eds., p. 458.

- 1 2 Dictionary of Historical Terms, Second Edition (1998) Chris Cook, Ed., pp. 192–193

- ↑ Dictionary of Historical Terms, Second Edition (1998) Chris Cook, Ed., pp. 13–13

Sources

- Ree, E. Van (March 1997). "Stalin and Marxism: A Research Note". Studies in East European Thought. Springer. 49 (1): 23–33. JSTOR 20099624.

- Daniels, Robert Vincent (2007). The Rise and Fall of Communism in Russia. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300106491.

- Bottomore, T. B. A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Malden, Massachusetts, USA; Oxford, England, UK; Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Berlin, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991 ISBN 0631180826.

- Lee, Stephen J. European Dictatorships, 1918–1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000 ISBN 0415230462.

- Pons, Silvo and Service, Robert (eds.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press ISBN 0691154295.

- Ulam, Adam Bruno. The Bolsheviks: The Intellectual and Political History of the Triumph of Communism in Russia. Harvard University Press, 1965, 1998 ISBN 0674078306.

External links

- "Marxism–Leninism". Marxists.org.

- Fundamentals of Marxism–Leninism.

- "Leninist Ebooks".

- In Defense of Communism.

- Alexander Spirkin, Sergei Syrovatkin (1990). Fundamentals of Philosophy. Moscow. Progress Publishers.