Legislature

| Legislature |

|---|

| Chambers |

| Parliament |

| Parliamentary procedure |

| Types |

| Legislatures by country |

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

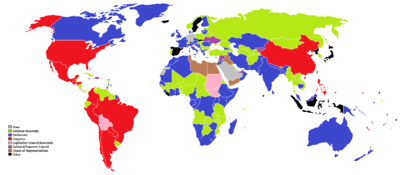

A legislature is a deliberative assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. Legislatures form important parts of most governments; in the separation of powers model, they are often contrasted with the executive and judicial branches of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are known as primary legislation. Legislatures observe and steer governing actions and usually have exclusive authority to amend the budget or budgets involved in the process.

The members of a legislature are called legislators. In a democracy, legislators are most commonly popularly elected, although indirect election and appointment by the executive are also used, particularly for bicameral legislatures featuring an upper chamber.

Terminology

Names for national legislatures include "parliament", "congress", "diet", and "assembly", depending on country.

Internal organization

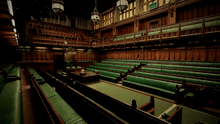

Each chamber of the legislature consists of a number of legislators who use some form of parliamentary procedure to debate political issues and vote on proposed legislation. There must be a certain number of legislators present to carry out these activities; this is called a quorum.

Some of the responsibilities of a legislature, such as giving first consideration to newly proposed legislation, are usually delegated to committees made up of a few of the members of the chamber(s).

The members of a legislature usually represent different political parties; the members from each party generally meet as a caucus to organize their internal affairs.

The internal organization of a legislature is also shaped by the informal norms that are shared by its members.

Power

Legislatures vary widely in the amount of political power they wield, compared to other political players such as judiciaries, militaries, and executives. In 2009, political scientists M. Steven Fish and Matthew Kroenig constructed a Parliamentary Powers Index in an attempt to quantify the different degrees of power among national legislatures. The German Bundestag, the Italian Parliament, and the Mongolian State Great Khural tied for most powerful, while Myanmar's House of Representatives and Somalia's Transitional Federal Assembly (since replaced by the Federal Parliament of Somalia) tied for least powerful.[1]

Some political systems follow the principle of legislative supremacy, which holds that the legislature is the supreme branch of government and cannot be bound by other institutions, such as the judicial branch or a written constitution. Such a system renders the legislature more powerful.

In parliamentary and semi-presidential systems of government, the executive is responsible to the legislature, which may remove it with a vote of no confidence. On the other hand, according to the separation of powers doctrine, the legislature in a presidential system is considered an independent and coequal branch of government along with both the judiciary and the executive.[2]

Legislatures will sometimes delegate their legislative power to administrative or executive agencies.[3]

Members

Legislatures are made up of individual members, known as legislators, who vote on proposed laws. A legislature usually contains a fixed number of legislators; because legislatures usually meet in a specific room filled with seats for the legislators, this is often described as the number of "seats" it contains. For example, a legislature that has 100 "seats" has 100 members. By extension, an electoral district that elects a single legislator can also be described as a "seat", as, for, example, in the phrases "safe seat" and "marginal seat".

Chambers

A legislature may debate and vote upon bills as a single unit, or it may be composed of multiple separate assemblies, called by various names including legislative chambers, debate chambers, and houses, which debate and vote separately and have distinct powers. A legislature which operates as a single unit is unicameral, one divided into two chambers is bicameral, and one divided into three chambers is tricameral.

In bicameral legislatures, one chamber is usually considered the upper house, while the other is considered the lower house. The two types are not rigidly different, but members of upper houses tend to be indirectly elected or appointed rather than directly elected, tend to be allocated by administrative divisions rather than by population, and tend to have longer terms than members of the lower house. In some systems, particularly parliamentary systems, the upper house has less power and tends to have a more advisory role, but in others, particularly presidential systems, the upper house has equal or even greater power.

In federations, the upper house typically represents the federation's component states. This is a case with the supranational legislature of the European Union. The upper house may either contain the delegates of state governments – as in the European Union and in Germany and, before 1913, in the United States – or be elected according to a formula that grants equal representation to states with smaller populations, as is the case in Australia and the United States since 1913.

Tricameral legislatures are rare; the Massachusetts Governor's Council still exists, but the most recent national example existed in the waning years of White-minority rule in South Africa. Tetracameral legislatures no longer exist, but they were previously used in Scandinavia.

Size

Legislatures vary widely in their size. Among national legislatures, China's National People's Congress is the largest with 2 980 members, while Vatican City's Pontifical Commission is the smallest with 7. Neither legislature is democratically elected, with the National People's Congress being indirectly elected, as well as this the National People's Congress has little independent power.

Legislature size is a trade off between efficiency and representation; the smaller the legislature, the more efficiently it can operate, but the larger the legislature, the better it can represent the political diversity of its constituents. Comparative analysis of national legislatures has found that size of a country's lower house tends to be proportional to the cube root of its population; that is, the size of the lower house tends to increase along with population, but much more slowly.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Fish, M. Steven; Kroenig, Matthew (2009). The handbook of national legislatures: a global survey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51466-8.

- ↑ "Governing Systems and Executive-Legislative Relations (Presidential, Parliamentary and Hybrid Systems)". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ↑ Schoenbrod, David (2008). "Delegation". In Hamowy, Ronald. The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 117–18. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n74. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- ↑ Frederick, Brian (December 2009). "Not Quite a Full House: The Case for Enlarging the House of Representatives". Bridgewater Review. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

Further reading

- Bauman, Richard W.; Kahana, Tsvi, eds. (2006). The least-examined branch: the role of legislatures in the constitutional state. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85954-7.

- Carey, John M. (2006). "Legislative organization". The Oxford handbook of political institutions. Oxford University Press. pp. 431–454. ISBN 978-0-19-927569-4.

- Martin, Shane; Saalfeld, Thomas; Strøm, Kaare W., eds. (2014). The Oxford handbook of legislative studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-191-01907-4.

- Olson, David M. (2015). Democratic legislative institutions: a comparative view. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-47314-5.