Xi Jinping

| Xi Jinping | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 习近平 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Assumed office 15 November 2012 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hu Jintao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7th President of the People's Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Assumed office 14 March 2013 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Li Keqiang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President |

Li Yuanchao Wang Qishan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hu Jintao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central Military Commission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Assumed office 15 November 2012 (Party Commission) 14 March 2013 (State Commission) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy |

Fan Changlong Xu Qiliang Zhang Youxia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hu Jintao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

15 June 1953 Beijing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Communist Party of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) |

Ke Lingling (m. 1979; div. 1982) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Xi Mingze (daughter) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

Xi Zhongxun (father) Qi Xin (mother) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives |

Qi Qiaoqiao (sister) Deng Jiagui (brother-in-law) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Residence | Zhongnanhai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Tsinghua University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service/branch |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1979–1982 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit | General Office of the Central Military Commission (1979–1982, as a secretary of Defense Minister Geng Biao) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Central institution membership

Leading Groups and Commissions

Other offices held

the People's Republic of China

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xi Jinping | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) "Xi Jinping" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 习近平 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 習近平 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of China |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related topics |

Xi Jinping (/ʃiː/;[2][3] Chinese: 习近平; born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician currently serving as General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC),[4] President of the People's Republic of China,[5] and Chairman of the Central Military Commission.[6] Often described as China's "paramount leader", in 2016 the CPC officially gave him the title of "core leader".[7] As General Secretary, Xi holds an ex-officio seat on the Politburo Standing Committee of the Communist Party of China, China's top decision-making body.[8]

Xi is the first General Secretary to have been born after the Second World War. The son of Chinese Communist veteran Xi Zhongxun, he was exiled to rural Yanchuan County as a teenager following his father's purge during the Cultural Revolution, and lived in a cave in the village of Liangjiahe, where he organized communal laborers.[9] After studying at the prestigious Tsinghua University as a "Worker-Peasant-Soldier Student",[10] Xi rose through the ranks politically in China's coastal provinces. Xi was governor of Fujian province from 1999 to 2002, and governor, then party secretary of neighboring Zhejiang province from 2002 to 2007. Following the dismissal of Chen Liangyu, Xi was transferred to Shanghai as party secretary for a brief period in 2007. Xi joined the Politburo Standing Committee and central secretariat in October 2007, spending the next five years as Hu Jintao's presumed successor. Xi was vice president from 2008 to 2013 and Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission from 2010 to 2012.

Since assuming power, Xi has introduced far-ranging measures to enforce party discipline and to ensure internal unity. His signature anti-corruption campaign has led to the downfall of prominent incumbent and retired Communist Party officials, including members of the Politburo Standing Committee.[11] Described as a Chinese nationalist,[12] Xi has tightened restrictions over civil society and ideological discourse, advocating internet censorship in China as the concept of "internet sovereignty".[13][14] Xi has called for further socialist market economic reforms, for governing according to the law and for strengthening legal institutions, with an emphasis on individual and national aspirations under the slogan "Chinese Dream".[15] Xi has also championed a more assertive foreign policy, particularly with regard to China–Japan relations, China's claims in the South China Sea, and its role as a leading advocate of free trade and globalization.[16] He has also sought to expand China's Eurasian influence through the One Belt One Road Initiative.[11] The 2015 meeting between Xi and Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou marked the first time the political leaders of both sides of the Taiwan Strait met since the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1950.[17]

Considered the central figure of the fifth generation of leadership of the People's Republic,[18] Xi has significantly centralized institutional power by taking on a wide range of leadership positions, including chairing the newly formed National Security Commission, as well as new steering committees on economic and social reforms, military restructuring and modernisation, and the Internet. Said to be one of the most powerful leaders in modern Chinese history, Xi's political thoughts have been written into the party and state constitutions, and under his leadership the latter was amended to abolish term limits for the presidency.[19] In 2018, Forbes ranked Xi as the most powerful and influential person in the world, dethroning Vladimir Putin who held the record for 5 consecutive years.[20][21][22]

Early life and education

Xi Jinping was born in Beijing on 15 June 1953. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949 by Mao Zedong, Xi's father held a series of posts, including propaganda chief, vice-premier, and vice-chairman of the National People's Congress.[23] Xi's father is from Fuping County, Shaanxi, and Xi could further trace his patrilineal descent from Xiying in Dengzhou, Henan.[24] He is the second son of Xi Zhongxun and his wife Qi Xin.[25]

In 1963, when Xi was age 10, his father was purged from the Party and sent to work in a factory in Luoyang, Henan.[26] In May 1966, Xi's secondary education was cut short by the Cultural Revolution, when all secondary classes were halted for students to criticise and fight their teachers. The Xi family home was ransacked by student militants and one of Xi's sisters, Xi Heping, was killed.[27] Later, his mother was forced to publicly denounce him as Xi was paraded before a crowd as an enemy of the revolution. Xi was aged 15 when his father was imprisoned in 1968 during the Cultural Revolution; Xi would not see his father again until 1972. Without the protection of his father, Xi was sent to work in Liangjiahe Village, Wen'anyi Town, Yanchuan County, Yan'an, Shaanxi, in 1969 in Mao Zedong's Down to the Countryside Movement.[28] After a few months, unable to stand rural life, he ran away to Beijing. He was arrested during a crackdown on deserters from the countryside and sent to a work camp to dig ditches.[29] He later became the Party branch secretary of the production team, leaving that post in 1975. When asked about this experience later by Chinese state television, Xi recalled, "It was emotional. It was a mood. And when the ideals of the Cultural Revolution could not be realised, it proved an illusion."[30]

From 1975 to 1979, Xi studied chemical engineering at Beijing's prestigious Tsinghua University as a "Worker-Peasant-Soldier student", where engineering majors spent about one-fifth of their time studying Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong thought, doing farm work and "learning from the People's Liberation Army".[10]

From 1979 to 1982, Xi served as secretary for his father's former subordinate Geng Biao, the then vice premier and secretary-general of the Central Military Commission. This gained Xi some military background. In 1985, as part of a Chinese delegation to study U.S. agriculture, he stayed in the home of an American family in the town of Muscatine, Iowa.[31] This trip, and his two-week stay with a U.S. family, is said to have had a lasting impression upon him and his views on the United States.[32]

From 1998 to 2002, he studied Marxist philosophy and ideological education in an "on-the-job" postgraduate programme at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, again at Tsinghua University, and obtained a Doctor of Law (LLD) degree, which was a degree covering fields of law, politics, management, and revolutionary history.[33]

Rise to power

Xi joined the Communist Youth League of China in 1971 and he applied in 1973 to join the Communist Party of China 10 times and finally got in on the tenth attempt in 1974.[34][35] In 1982, he was sent to Zhengding County in Hebei as deputy Party Secretary of Zhengding County. He was promoted in 1983 to Secretary, becoming the top official of the county.[36] Xi subsequently served in four provinces during his regional political career: Hebei (1982–1985), Fujian (1985–2002), Zhejiang (2002–2007), and Shanghai (2007).

Xi held posts in the Fuzhou Municipal Party Committee and became the president of the Party School in Fuzhou in 1990. In 1997, Xi was named an alternate member of the 15th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. However, out of the 151 alternate members of the Central Committee elected at the 15th Party Congress, Xi received the lowest number of votes in favour, placing him in last place in the rankings of members, ostensibly due to his status as a princeling.[lower-alpha 1][37]

In 1999, he was promoted to the office of Vice Governor of Fujian, then he became governor a year later. In Fujian, Xi made efforts to attract investment from Taiwan and to strengthen the private sector of the provincial economy.[38] In February 2000, he and then-provincial Party Secretary Chen Mingyi were called before the top members of the Party Central Politburo Standing Committee of the Communist Party of China – general secretary Jiang Zemin, Premier Zhu Rongji, Vice-President Hu Jintao and Discipline Inspection secretary Wei Jianxing – to explain aspects of the Yuanhua scandal.[39]

In 2002, Xi left Fujian and took up leading political positions in neighbouring Zhejiang, eventually taking over as provincial party chief after several months as acting governor, occupying a top provincial office for the first time in his career. In 2002, Xi was elected a full member of the 16th Central Committee, marking his ascension to the national stage. While in Zhejiang, Xi presided over reported growth rates averaging 14% per year.[40] His career in Zhejiang was marked by a tough and straightforward stance against corrupt officials, which earned him a name on the national media and drew the attention of China's top leaders.[41]

Following the dismissal of Shanghai Party Chief Chen Liangyu in September 2006 due to a social security fund scandal, Xi was transferred to Shanghai in March 2007 to become the party chief of Shanghai.[42] Xi spent only seven months in Shanghai, but his appointment to one of the most important regional posts in China sent a clear signal that Xi was highly regarded by China's top leadership. In Shanghai, Xi avoided controversy, and was known for strictly observing party discipline. For example, Shanghai administrators attempted to earn favour with Xi by arranging a special train to shuttle him between Shanghai and Hangzhou in order for him to complete handing off his work to his successor as Zhejiang party chief Zhao Hongzhu. However, Xi reportedly refused to take the train, citing a loosely enforced party regulation which stipulated that special trains can only be reserved for "national leaders".[43] While in Shanghai, he worked on preserving unity of the local party organization, and made a pledge that there would be no 'purges' during his administration, despite the fact that many local officials were thought to have been implicated in the Chen Liangyu corruption scandal.[44] On most issues Xi largely echoed the line of the central leadership.[45]

Politburo Standing Committee member

Xi was appointed to the nine-man Politburo Standing Committee of the Communist Party of China at the 17th Party Congress in October 2007. Xi was ranked above Li Keqiang, an indication that he was going to succeed Hu Jintao as China's next leader. In addition, Xi also held the top-ranking membership of the Communist Party's Central Secretariat. This assessment was further supported at the 11th National People's Congress in March 2008, when Xi was elected as Vice-President of the People's Republic of China.[46]

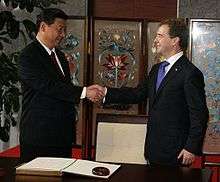

Following his elevation, Xi has held a broad range of portfolios. He was put in charge of the comprehensive preparations for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, as well as being the central government's leading figure in Hong Kong and Macau affairs. In addition, he also became the new President of the Central Party School of the Communist Party of China, the cadre-training and ideological education wing of the Communist Party. In the wake of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, Xi visited disaster areas in Shaanxi and Gansu. Xi made his first foreign trip as vice president to North Korea, Mongolia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Yemen from 17 to 25 June 2008.[47] After the Olympics, Xi was assigned the post of Committee Chair for the preparations of the 60th Anniversary Celebrations of the founding of the People's Republic of China. He was also reportedly at the helm of a top-level Communist Party committee dubbed the 6521 Project, which was charged with ensuring social stability during a series of politically sensitive anniversaries in 2009.[48]

Xi is considered to be one of the most successful members of the Crown Prince Party, a quasi-clique of politicians who are descendants of early Chinese Communist revolutionaries. Former Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, when asked about Xi, said he felt he was "a thoughtful man who has gone through many trials and tribulations."[49] Lee also commented: "I would put him in the Nelson Mandela class of persons. A person with enormous emotional stability who does not allow his personal misfortunes or sufferings affect his judgment. In other words, he is impressive".[50] Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson described Xi as "the kind of guy who knows how to get things over the goal line."[51] Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said that Xi "has sufficient reformist, party and military background to be very much his own man."[52] Former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton tweeted, "Xi hosting a meeting on women's rights at the UN while persecuting feminists? Shameless."[53]

Trips as Vice President and Mexico commentary incident

In February 2009, in his capacity as vice-president, Xi Jinping embarked on a tour of Latin America, visiting Mexico,[54][55] Jamaica,[56][57] Colombia,[58][59] Venezuela,[60][61] and Brazil[62] to promote Chinese ties in the region and boost the country's reputation in the wake of the global financial crisis. He also visited Valletta, Malta, before returning to China.[63][64]

On 11 February, while visiting Mexico, Xi spoke in front of a group of overseas Chinese and explained China's contributions to the financial crisis, saying that it was "the greatest contribution towards the whole of human race, made by China, to prevent its 1.3 billion people from hunger".[65] Xi went on to remark: "There are some bored foreigners, with full stomachs, who have nothing better to do than point fingers at us. First, China doesn't export revolution; second, China doesn't export hunger and poverty; third, China doesn't come and cause you headaches. What more is there to be said?"[66][67] The story was reported on some local television stations. The news led to a flood of discussions on Chinese internet forums. It was reported that the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs was caught off-guard by Xi's remarks, as the actual video was shot by some accompanying Hong Kong reporters and broadcast on Hong Kong TV, which then turned up in various internet video websites.[68]

Xi continued his international trips, some say to burnish his foreign affairs credentials prior to taking the helm of China's leadership. In the European Union, Xi visited Belgium, Germany, Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania from 7 October to 21 2009.[69] Xi visited Japan, South Korea, Cambodia, and Myanmar on his Asian trip from 14 to 22 December 2009.[70]

Xi visited the United States, Ireland and Turkey in February 2012. The visit included meeting with then U.S. President Barack Obama at the White House[71] and then Vice President Joe Biden; and stops in California and Iowa, where he met with the family which previously hosted him during his 1985 tour as a Hebei provincial official.[72]

Disappearance

A few months before his ascendancy to the party leadership, Xi Jinping disappeared from official media coverage for several weeks beginning on 1 September 2012. On 4 September, he cancelled a meeting with U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and later also cancelled meetings with Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and a top Russian official. It was said that Xi effectively "went on strike" in preparation for the power transition in order to install political allies in key roles.[73] The Washington Post reported that Xi may have been injured in an altercation during a meeting of the "red second generation" which turned violent.[74]

Leadership

Accession to top posts

On 15 November 2012, Xi Jinping was elected to the post of General Secretary of the Communist Party and Chairman of the CPC Central Military Commission by the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, making him – informally – the paramount leader and the first one to be born in the People's Republic of China and not a preceding Chinese state. On the following day, Xi led the new line-up of the Politburo Standing Committee onto the stage in their first public appearance.[75] The new Standing Committee decreased its number of seats from nine to seven, with only Xi himself and Li Keqiang retaining their seats from the previous Standing Committee; the remaining members were new.[76][77][78] In a marked departure from the common practice of Chinese leaders, Xi's first speech as general secretary was plainly worded and did not include any political slogans or mention of his predecessors.[79] Xi mentioned the aspirations of the average person, remarking, "Our people ... expect better education, more stable jobs, better income, more reliable social security, medical care of a higher standard, more comfortable living conditions, and a more beautiful environment." Xi also vowed to tackle corruption at the highest levels, alluding that it would threaten the Party's survival; he was reticent about far-reaching economic reforms.[80]

In December 2012, Xi visited Guangdong in his first trip outside of Beijing since taking the Party leadership. The overarching theme of the trip was to call for further economic reform and a strengthened military. Xi visited the statue of Deng Xiaoping and his trip was described as following in the footsteps of Deng's own southern trip in 1992, which provided the impetus for further economic reforms in China after conservative party leaders stalled many of Deng's reforms in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. On his trip, Xi consistently alluded to his signature slogan the "Chinese Dream". "This dream can be said to be the dream of a strong nation. And for the military, it is a dream of a strong military", Xi told sailors.[81] Xi's trip was significant in that he departed from established convention of Chinese leaders' travel routine in multiple ways. Rather than dining out, Xi and his entourage ate regular hotel buffet. He traveled in a large van with his colleagues rather than a fleet of limousines, and did not restrict traffic on the parts of the highway he traveled on.[82]

Xi was elected President of the People's Republic of China on 14 March 2013, in a confirmation vote by the 12th National People's Congress in Beijing. He received 2,952 for, one vote against, and three abstentions.[83] He replaced Hu Jintao, who retired after serving two terms.[84]

In his new capacity as president, on 16 March 2013 Xi expressed support for noninterference in China–Sri Lanka relations amid a United Nations Security Council vote to condemn that country over government abuses during the Sri Lankan Civil War.[85] On 17 March, Xi and his new ministers arranged a meeting with the chief executive of Hong Kong, CY Leung, confirming his support for Leung.[86] Within hours of his election, Xi discussed cyber security and North Korea with U.S. President Barack Obama over the phone, who announced the visits of Treasury and State secretaries Jacob Lew and John F. Kerry to China the following week.[87] Within a week of his assuming the Presidency, Xi embarked on a trip to Russia, Tanzania, South Africa, and Republic of Congo.[88]

Announcing reforms

In November 2013, at the conclusion of the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee, the Communist Party delivered a far-reaching reform agenda that alluded to changes in both economic and social policy. Xi signaled at the plenum that he was consolidating control of the massive internal security organization that was formerly the domain of Zhou Yongkang.[89] A new National Security Commission was formed with Xi Jinping at its helm. The Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms – another ad-hoc policy coordination body led by Xi – was also formed to oversee the implementation of the reform agenda.

The reforms, termed "comprehensive deepening reforms" (全面深化改革; quánmiàn shēnhuà gǎigé) were said to be the most significant since Deng Xiaoping's 1992 "Southern Tour". In the economic realm, the Plenum announced that "market forces" would begin to play a "decisive" role in allocating resources.[89] This meant that the state would gradually reduce its involvement in the distribution of capital, and restructure state-owned enterprises to allow further competition, potentially by attracting foreign and private sector players in industries that were highly regulated previously. This policy aimed to address the bloated state sector that had unduly profited from an earlier round of re-structuring by purchasing assets at below-market prices, assets which were no longer being used productively. The Plenum also resolved to abolish the laogai system of "re-education through labour" which was largely seen as a blot on China's human rights record. The system has faced significant criticism for years from domestic critics and foreign observers.[89] The one-child policy was also abolished, resulting in a shift to a two-child policy since 1 January 2016.[90][91]

In December 2013, Xi arrived unannounced at a small Beijing restaurant to have steamed buns for lunch, with only one person accompanying him. He paid for the meal himself and dined with regular patrons.[92] Xi was applauded for the 'common touch' of the visit, and images were circulated widely on social media.[92]

Anti-corruption campaign

Xi vowed to crack down on corruption almost immediately after he ascended to power at the 18th Party Congress. In his 'inaugural speech' as general secretary, Xi mentioned that fighting corruption was one of the toughest challenges for the party.[93] A few months into his term, Xi outlined the "eight-point guide", listing out rules intended to curb corruption and waste during official party business; it aimed at stricter discipline on the conduct of party officials. Xi also vowed to root out "tigers and flies", that is, high-ranking officials and ordinary party functionaries.[94] During the first two years of Xi's term, he initiated cases against former Central Military Commission vice-chairman Xu Caihou, former Politburo Standing Committee member and security chief Zhou Yongkang, and former Hu Jintao chief aide Ling Jihua.[95]

Along with new disciplinary chief Wang Qishan, Xi's administration spearheaded the formation of "centrally-dispatched inspection teams" (中央巡视组), essentially cross-jurisdictional squads of officials whose main task was to gain more in-depth understanding of the operations of provincial and local party organizations, and in the process, also enforce party discipline mandated by Beijing. Many of the work teams also had the effect of identifying and initiating investigations on high-ranking officials. Over one hundred provincial-ministerial level officials were implicated during a massive nationwide anti-corruption campaign. These include former and current regional officials (Su Rong, Bai Enpei, Wan Qingliang), leading figures of state-owned enterprises and central government organs (Song Lin, Liu Tienan), and highly ranked generals in the military (Gu Junshan). In June 2014, the Shanxi provincial political establishment was decimated, with four officials dismissed within a week from the provincial party organization's top ranks. Within the first two years of the campaign alone, over 200,000 low-ranking officials received warnings, fines, and demotions.[96]

Consolidation of power

Political observers have called Xi the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong, especially since the ending of presidential two-term limits in 2018.[97][98][99][100] Xi has notably departed from the collective leadership practices of his post-Mao predecessors, centralising his power and creating working groups with himself at the head in order to subvert government bureacracy, making himself become the unmistakable central figure of the new administration.[101]

Beginning in 2013, the party under Xi has created a series of new "Central Leading Groups", that is, supra-ministerial steering committees, to bypass existing institutions when making decisions, and ostensibly making policy-making a more efficient process. The most notable new body is the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms, which has broad jurisdiction over economic restructuring and social reforms, said to have displaced some of the power previously held by the State Council and its Premier.[102] Xi also became the leader of the Central Leading Group for Internet Security and Informatization, in charge of cyber-security and internet policy. The Third Plenum held in 2013 also saw the creation of the National Security Commission of the Communist Party of China, another body chaired by Xi which is believed to have ultimate oversight over issues of national security such as combating terrorism, intelligence, espionage, ultimately incorporating many areas of jurisdiction formerly vested in the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission under Zhou Yongkang.

Xi has also been active in his participation in military affairs, taking a direct hands-on approach to military reform. In addition to being the Chairman of the Central Military Commission, and the leader of the Central Leading Group for Military Reform founded in 2014 to oversee comprehensive military reforms, Xi has delivered numerous high-profile pronouncements vowing to clean up malfeasance and complacency in the military, aiming to build a more effective fighting force. In addition, Xi held the "New Gutian Conference" in 2014, gathering China's top military officers, re-emphasizing the principle of "the party has absolute control over the army" first established by Mao at the 1929 Gutian Conference.[103] According to a University of California, San Diego expert on Chinese military, Xi "has been able to take political control of the military to an extent that exceeds what Mao and Deng have done".[104]

On 21 April 2016 Xi was named "commander in chief" of the country's new Joint Operations Command Center of the People's Liberation Army by Xinhua news agency and the broadcaster China Central Television.[105][106] Some analysts interpreted this move as an attempt to display strength and strong leadership and as being more "political than military".[107] According to Ni Lexiong, a military affairs expert, Xi "not only controls the military but also does it in an absolute manner, and that in wartime, he is ready to command personally".[108]

Cult of personality

Xi has had a cult of personality constructed around himself since entering office[109][110] "with books, cartoons, pop songs and even dance routines" honouring his rule.[111] Following Xi's ascension to the leadership core of the CPC, he has been referred to as Xi Dada (Uncle or Papa Xi),[111] echoing a greeting used in old China towards their emperors.[112] The village of Liangjiahe, in which Xi was sent to work, has become a "modern-day shrine" decorated with Communist propaganda and murals extolling the formative years of Xi's life.[113]

Legal reforms

The party under Xi announced a raft of legal reforms at the Fourth Plenum held in the fall 2014, and Xi called for "Chinese socialistic rule of law" immediately afterwards. The party aimed to reform the legal system which had been perceived as ineffective at delivering justice and affected by corruption, local government interference, and lack of constitutional oversight. The plenum, while emphasizing the absolute leadership of the party, also called for a greater role of the constitution on the affairs of state, and a strengthening of the role of the National People's Congress Standing Committee in interpreting the constitution.[114] It also called for more transparency in legal proceedings, more involvement of ordinary citizens in the legislative process, and an overall "professionalization" of the legal workforce. The party also planned to institute cross-jurisdictional circuit legal tribunals as well as giving provinces consolidated administrative oversight over lower level legal resources, which is intended to have the effect of reducing local government involvement in legal proceedings.[115]

Foreign trips as President

Xi made his first foreign trip as president to Russia on 22 March 2013, about a week after he assumed the presidency. He met with President Vladimir Putin and the two leaders discussed trade and energy issues. He then went onto Tanzania, South Africa (where he attended the BRICS summit in Durban), and the Republic of the Congo.[116] Xi visited the United States at Sunnylands Estate in California in a 'shirtsleeves summit' with U.S. President Barack Obama in June 2013, although this was not considered a formal state visit.[117] In October 2013 Xi attended the APEC Summit in Bali, Indonesia.

Xi made a trip to Western Europe in March 2014, visiting the Netherlands, where he attended the Nuclear Security Summit in The Hague, followed by France, Germany, and Belgium.[118] Xi made a state visit to South Korea on 4 July 2014 and met with South Korean President Park Geun-hye.[119] Between 14 and 23 July, Xi attended the BRICS leaders' summit in Brazil and also visited Argentina, Venezuela, and Cuba.[120]

Xi went on an official state visit to India and met with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in September 2014; he visited New Delhi but also went to Modi's hometown in the state of Gujarat.[121] Xi went on a state visit to Australia and met with Prime Minister Tony Abbott in November 2014,[122] followed by a visit to the island nation of Fiji.[123] Xi visited Pakistan in April 2015, signing a series of deals over infrastructure related to the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, before heading to Jakarta and Bandung, Indonesia, to attend the Afro-Asian Leaders Summit and the 60th Anniversary events of the Bandung Conference.[124] Xi visited Russia and was the guest-of-honour of Russian president Vladimir Putin at the 2015 Moscow Victory Day Parade to mark the 70th Anniversary of the victory of the allies in Europe. At the parade Xi and his wife Peng Liyuan sat next to Putin. On the same trip Xi also visited Kazakhstan and met with that country's president Nursultan Nazarbayev, and also met with Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus.[125]

In September 2015, Xi made his first state visit to the United States.[126][127][128] In October 2015, Xi made a state visit to the United Kingdom, the first by a Chinese leader for a decade.[129] This followed a visit to China in March 2015 by the Duke of Cambridge. During the state visit, Xi met Queen Elizabeth II, British Prime Minister David Cameron and other dignitaries. Increased customs, trade and research collaborations between China and the UK were discussed, but more informal events also took place including a visit to Manchester City's football academy.[130]

In March 2016, Xi visited the Czech Republic on his way to United States of America. In Prague, he met with the Czech president, prime minister and other representatives, to promote relations and economic cooperation between the Czech Republic and the People's Republic of China.[131] His visit was met by a considerable number of protests by Czech people.[132]

In January 2017, Xi became the first Chinese President to plan to attend the World Economic Forum in Davos.[133] On January 17, Xi addressed the forum in a high-profile keynote, addressing globalization, the global trade agenda, and China's rising place in the world's economy and international governance; he made a series of pledges about China's defense of "economic globalization" and climate change accords.[134][135] Premier Li Keqiang attended the forum in 2015 and Vice-President Li Yuanchao did so in 2016. During the three day state visit to the country in 2017 Xi also visited the World Health Organization, the United Nations and the International Olympic Committee.[135]

Cultural revival

As Communist ideology plays a less central role in the lives of the masses in the People's Republic of China, top political leaders of the Communist Party of China such as Xi Jinping continue the rehabilitation of ancient Chinese philosophical figures like Han Fei into the mainstream of Chinese thought alongside Confucianism, both of which Xi sees as relevant. "He who rules by virtue is like the Pole Star," he said at a meeting of officials last year, quoting Confucius. "It maintains its place, and the multitude of stars pay homage." In Shandong, the Birthplace of Confucius, he told scholars that while the West was suffering a "crisis of confidence," the Communist Party had been "the loyal inheritor and promoter of China's outstanding traditional culture."[136]

Han Fei gained new prominence with favourable citations. One sentence of Han Fei's that Xi quoted appeared thousands of times in official Chinese media at the local, provincial, and national levels.[137]

Removal of term limits

In March 2018, the party-controlled National People's Congress passed a set of constitutional amendments including removal of term limits for the President and Vice President, the creation of a National Supervisory Commission, as well as enhancing the central role of the Communist Party.[138][139] On 17 March 2018, Xi was reappointed by the Chinese legislature as President, now without term limits, with Wang Qishan appointed as the Vice President.[140][141] The following day Li Keqiang was reappointed Premier and longtime allies of Xi Xu Qiliang and Zhang Youxia were voted in as vice-chairmen of state military commission.[142] Foreign minister Wang Yi was also promoted to state councillor and General Wei Fenghe was named defence minister.[143]

According to the British Financial Times, Xi Jinping expressed his views of constitutional amendment at meetings with Chinese officials and foreign dignitaries. Xi explained the decision in terms of needing to align two more powerful posts — General Secretary of the Communist Party and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) which are no term limits.[144] However, Xi did not say whether he intended to serve as party general secretary, CMC chairman and state president, for three or more terms.

Political positions

Chinese Dream

Xi and Communist Party ideologues coined the phrase "Chinese Dream" to describe his overarching plans for China as its leader. Since 2013, the phrase has emerged as the distinctive quasi-official ideology of the party leadership under Xi Jinping, much as the "Scientific Outlook on Development" was for Hu Jintao and the "Three Represents" was for Jiang Zemin. The origin of the term "Chinese Dream" is unclear. While the phrase has been used previously by journalists and scholars,[145] some publications have posited that the term likely drew its inspiration from the concept of the American Dream.[146] The Economist noted the abstract and seemingly accessible nature of the concept with no specific overarching policy stipulations may be a deliberate departure from the jargon-heavy ideologies of his predecessors.[147]

While the Chinese Dream was originally interpreted as an extension of the American Dream, which emphasizes individual self-improvement and opportunity,[147] the slogan's use in official settings since 2013 has taken on a noticeably more nationalistic character, with official pronouncements of the "Dream" being consistently linked with the phrase "great revival of the Chinese nation".[148] The policy implications of the "Chinese Dream" remain unclear.

Xi first used the phrase during a high-profile visit to the National Museum of China on 29 November 2012, where Xi and his Standing Committee colleagues were attending a "national revival" exhibition. Since then, the phrase has become the signature political slogan of the Xi era.[149]

Xi Jinping Thought

In September 2017, the Communist Party Central Committee had decided that Xi's political philosophies, generally referred to as "Xi Jinping Thought" by western media, would become part of the Party Constitution.[150][151]

Xi first made mention of the "Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era" in the opening day speech delivered to the 19th Party Congress in October 2017. His Politburo Standing Committee colleagues, in their own reviews of Xi's keynote address at the Congress, prepended the name "Xi Jinping" in front of "Thought".[152]

Xi himself has described the Thought as part of the broad framework created around Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, a Dengist term that places China in the "primary stage of socialism". In official party documentation and pronouncements by Xi's colleagues, the Thought is said to be a continuation of Marxism–Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the "Three Represents", and the Scientific Development Perspective, as part of a series of guiding ideologies that embody "Marxism adopted to Chinese conditions" and contemporary considerations.[152]

On 24 October 2017, at its closing session, the 19th Party Congress approved the incorporation of Xi Jinping Thought into the Constitution of the Communist Party of China.[153][97]

The concepts and context behind Xi Jinping Thought are elaborated in Xi Jinping's The Governance of China book series, published by the Foreign Languages Press for an international audience. Volume one was published in September 2014, followed by volume two in November 2017.[154]

Foreign policy

Xi has reportedly taken a hard line on security issues as well as foreign affairs, projecting a more nationalistic and assertive China on the world stage.[12] Xi's political program calls for a China more united and confident of its own value system and political structure.[155]

Under Xi China has also taken a more critical stance on North Korea, while improving relationships with South Korea.[156] China-Japan relations have soured under Xi's administration; the most thorny issue between the two countries remains the dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. In response to Japan's continued robust stance on the issue, China declared an Air Defense Identification Zone in November 2013.[157]

Xi has called China–United States relations in the contemporary world a "new type of great-power relations", a phrase the Obama administration had been reluctant to embrace.[158] Under his administration the Strategic and Economic Dialogue that began under Hu Jintao has continued. On China-U.S. relations, Xi said, "If [China and the United States] are in confrontation, it would surely spell disaster for both countries".[159] Xi met with President Obama privately at the Sunnylands ranch in California in 2013 in what became known as the "shirtsleeves summit". The U.S. has been critical of Chinese actions in the South China Sea.[158] In 2014, Chinese hackers compromised the computer system of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management,[160] resulting in the theft of approximately 22 million personnel records handled by the office.[161]

Xi has cultivated stronger relations with Russia, particularly in the wake of the Ukraine crisis of 2014. Xi seems to have developed a strong personal relationship with President Vladimir Putin, both of whom are viewed as strong leaders with a nationalist orientation who are not afraid to assert themselves against Western interests.[162] Xi attended the opening ceremonies of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. Under Xi, China signed a $400 billion gas deal with Russia; China has also become Russia's largest trading partner.[162]

Xi has signaled a greater interest in Central Asia as evidenced by China's One Belt One Road initiative.[163] Xi made the announcement while in Astana, Kazakhstan and called it a "golden opportunity".[164]

.jpg)

Xi has also indirectly spoken out critically on the U.S. "strategic pivot" to Asia.[165] Addressing a regional conference in Shanghai on 21 May 2014, Xi called on Asian countries to unite and forge a way together, rather than get involved with third party powers, seen as a reference to the United States. "Matters in Asia ultimately must be taken care of by Asians. Asia's problems ultimately must be resolved by Asians and Asia's security ultimately must be protected by Asians", he told the conference.[166]

In November 2014, in a major policy address, Xi has called for a decrease in the use of force, preferring dialogue and consultation to solve the current issues plaguing the relationship between China and its South East Asian neighbors.[167] In April 2015 Xi led a large delegation on a state visit to Pakistan. During his visit he signed energy and infrastructure deals worth $45 billion including the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. Pakistan's highest civilian award, the Nishan-e-Pakistan, was also conferred upon him.[168]

.jpg)

In April 2015, new satellite imagery revealed that China was rapidly constructing an airfield on Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly Islands of the South China Sea.[169] In May 2015, U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter warned the government of Xi Jinping to halt its rapid island-building in disputed territory in the South China Sea.[170]

.jpg)

In spite of what seemed to be a tumultuous start of Xi Jinping's leadership vis-à-vis the United-States, on 13 May 2017 Xi said at the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing: “We should foster a new type of international relations featuring 'win-win cooperation', and we should forge a partnership of dialogue with no confrontation, and a partnership of friendship rather than alliance. All countries should respect each other's sovereignty, dignity and territorial integrity; respect each other's development path and its social systems, and respect each other's core interests and major concerns... ...What we hope to create is a big family of harmonious coexistence.”[171]

Role of the Communist Party

Early on in his term, Xi repeatedly issued pronouncements on the supremacy of the Communist Party, largely echoing Deng Xiaoping's line that effective economic reform can only take place within the one-party political framework. In Xi's view, the Communist Party is the legitimate, constitutionally-sanctioned ruling party of China, and that the party derives this legitimacy through advancing the Mao-style "Mass Line Campaign"; that is the party represents the interests of the overwhelming majority of ordinary people. In this vein, Xi called for officials to practise mild self-criticism in order to appear less corrupt and more popular among the people.[172][173][174]

Xi's position has been described as preferring highly centralized political power as a means to direct large-scale economic restructuring.[175] Xi believes that China should be 'following its own path' and that a strong authoritarian government is an integral part of the "China model", operating on a "core socialist value system", which has been interpreted as China's alternative to Western values. However, Xi and his colleagues acknowledge the challenges to the legitimacy of Communist rule, particularly corruption by party officials. The answer, according to Xi's programme, is two-fold: strengthen the party from within, by streamlining strict party discipline and initiating a large anti-corruption campaign to remove unsavoury elements from within the party, and re-instituting the Mass Line Campaign externally to make party officials better understand and serve the needs of ordinary people. Xi believes that just as the party must be at the apex of political control of the state, the party's central authorities (i.e., the Politburo, PSC, or himself as general secretary) must exercise full and direct political control of all party activities.[176]

Xi's policies have been characterized as "economically liberal but politically conservative" by Cheng Li of the Brookings Institution.[156]

Censorship

The "Document No. 9" is a confidential internal document widely circulated within the Communist Party of China in 2013 by the party's General Office.[177][178] The document was first published in July 2012.[179] The document warns of seven dangerous Western values: constitutional democracy, universal values of human rights, civil society, pro-market neo-liberalism, media independence, historical nihilism (criticisms of past errors) and questioning the nature of Chinese style socialism.[180] Coverage of these topics in educational materials is forbidden.[181] The release of this internal document, which has introduced new topics that were previously not "off-limits", was seen as Xi's recognition of the "sacrosanct" nature of Communist Party rule over China.[180]

Since Xi Jinping became the General Secretary of the CPC censorship has been "significantly stepped up".[182] Chairing the 2018 China Cyberspace Governance Conference on 20 and 21 April 2018, Xi committed to "fiercely crack down on criminal offenses including hacking, telecom fraud, and violation of citizens' privacy."[183] His administration has also overseen more internet restrictions imposed in China, and is described as being "stricter across the board" on speech than previous administrations.[184] Xi's term has resulted in a further suppression of dissent from civil society. Xi's term has seen the arrest and imprisonment of activists such as Xu Zhiyong, as well as numerous others who identified with the New Citizens' Movement. Prominent legal activist Pu Zhiqiang of the Weiquan movement was also arrested and detained.[185] The situation for users of Weibo has been described as a change from fearing that individual posts would be deleted, or at worst one's account, to fear of arrest.[186] A law enacted in September 2013 authorized a three-year prison term for bloggers who shared more than 500 times any content considered "defamatory".[187] A group of influential bloggers were summoned by the State Internet Information Department to a seminar instructing them to avoid writing about politics, the Communist Party, or making statements contradicting official narratives. Many bloggers stopped writing about controversial topics, and Weibo went into decline, with much of its readership shifting to WeChat users speaking to very limited social circles.[187]

In July 2017, the character Winnie-the-Pooh was blocked on Chinese social media sites because bloggers had been comparing the plump bear to China's leader Xi Jinping.[188] This followed an incident where Chinese authorities censored a 9-year-old for comments about Xi's weight.[189]

Taiwan

In the 19th Party Congress held in 2017, Xi reaffirmed six out of the nine principles that had been affirmed continuously since the 16th Party Congress in 2002, with the notable exception of "Placing hopes on the Taiwan people as a force to help bring about unification".[190] According to the Brookings Institution, Xi used stronger language on potential Taiwan independence than his predecessors towards previous DPP governments in Taiwan.[190] In March 2018, Xi said that Taiwan would face the "punishment of history".[191]

Personal life

Xi married Ke Lingling, the daughter of Ke Hua, an ambassador to Britain in the early 1980s. They divorced within a few years.[192] The two were said to fight "almost every day" and, after the divorce, Ke moved to England.[193]

Xi married the prominent Chinese folk singer Peng Liyuan in 1987.[194] Peng Liyuan, a household name in China, was much better known to the public than Xi until his political elevation. The couple frequently lived apart due largely to their separate professional lives. Xi and Peng have a daughter named Xi Mingze, who graduated from Harvard University in the spring of 2015. While at Harvard, she used a pseudonym and studied psychology and English.[195] Xi's family have a home in Jade Spring Hill, a garden and residential area in north western Beijing run by the Central Military Commission.[196]

Peng described Xi as hardworking and down-to-earth. "When he comes home, I've never felt as if there's some leader in the house. In my eyes, he's just my husband."[197] Peng has played a much more visible role as China's "first lady" compared to her predecessors; for example, Peng hosted U.S. First Lady Michelle Obama on the latter's high-profile visit to China in March 2014.[198] Xi was described in a 2011 The Washington Post article by those who know him as "pragmatic, serious, cautious, hard-working, down to earth and low-key". Xi was described as a good hand at problem solving and "seemingly uninterested in the trappings of high office".[199] He is known to love U.S. films such as Saving Private Ryan, The Departed and The Godfather.[200][201] He also praised the independent film-maker Jia Zhangke.[202]

In June 2012, Bloomberg reported that members of Xi's extended family have substantial business interests, although there was no evidence he had intervened to assist them.[203] The Bloomberg website was blocked in mainland China in response to the article.[204] Since Xi embarked on an anti-corruption campaign, members of his family were reported by The New York Times to be selling their corporate and real estate investments beginning in 2012.[205]

Relatives of highly placed Chinese officials, including seven current and former senior leaders of the Politburo of the Communist Party of China, have been named in the Panama Papers, including Deng Jiagui,[206] the brother-in-law of Xi. Deng had two shell companies in the British Virgin Islands while Xi was a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, but they were dormant by the time Xi became General Secretary of the Communist Party in November 2012.[207]

Honours

- Foreign Honours

.svg.png)

- Key to the City

.svg.png)

See also

Notes

- ↑ It should be noted that Liu Yandong, Wang Qishan, and Deng Pufang (Deng Xiaoping's son) all placed among the bottom of the alternate member list. Like Xi, all three were seen as "princelings". It should also be noted that Bo Xilai did not get elected to the Central Committee at all; that is, Bo placed lower in the vote count compared to Xi.

References

- ↑ "Association for Conversation of Hong Kong Indigenous Languages Online Dictionary Archived 1 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. for Hong Kong Hakka and Hong Kong Punti (Weitou dialect)".

- ↑ "Xi". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ "How to Say: Chinese leaders' names". Magazine Monitor. BBC. 15 November 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ↑ "China's 'Chairman of Everything': Behind Xi Jinping's Many Titles". The New York Times. 2017-10-25.

Mr. Xi’s most important title is general secretary, the most powerful position in the Communist Party. In China’s one-party system, this ranking gives him virtually unchecked authority over the government.

- ↑ "Who's Who in China's New Communist Party Leadership Lineup". Bloomberg. 2012-11-15.

Xi Jinping, 59, was named general secretary of the 82-million-member Communist Party and is set to take over the presidency, a mostly ceremonial post, from Hu Jintao in March.

- ↑ Who's Who in China's Leadership Archived 2016-08-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Wu, Zhong (2016-10-23). "All hail Xi, China's third 'core' leader". www.atimes.com. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- ↑ "A simple guide to the Chinese government". South China Morning Post.

Xi Jinping is the most powerful figure in the Chinese political system. He is the President of China, but his real influence comes from his position as the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party.

- ↑ "For China's Rising Leader, A Cave Was Once Home". npr.org.

- 1 2 Denis Fred Simon; Cong Cao (19 March 2009). China's Emerging Technological Edge: Assessing the Role of High-End Talent. Cambridge University Press. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-521-88513-3.

- 1 2 "China's Soft-Power Deficit Widens as Xi Tightens Screws Over Ideology". the China Brief. Brookings Institution. 5 December 2014.

- 1 2 Kuhn, Robert Lawrence (6 June 2013). "Xi Jinping, a nationalist and a reformer". South China Morning Post.

- ↑ Tiezzi, The, Shannon. "China's 'Sovereign Internet'". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- ↑ Ford, Peter (2015-12-18). "On Internet freedoms, China tells the world, 'leave us alone'". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- ↑ "Xi Jinping calls for a Chinese dream, Daily Telegraph". Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ 王毅:指導新形勢下中國外交的強大思想武器 [Wang Yi: Powerful ideological weaponry for the purpose of channelling China under new circumstances)]. Communist Party of China News (in Chinese). Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ↑ Perlez, Jane; Ramzy, Austin (4 November 2015). "China, Taiwan and a Meeting After 66 Years". New York Times. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ "deckblatt-ca-data sup-form.pdf" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ Choi, Chi-yuk; Jun, Mai (2017-09-18). "Xi Jinping's political thought will be added to Chinese Communist Party constitution, but will his name be next to it?". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2017-09-22.

- ↑ "Xi Jinping becomes world's most powerful leader, Modi ranked 9th: Forbes- News Nation". News Nation. 9 May 2018.

- ↑ Bosilkovski, David M. Ewalt,Igor. "The World's Most Powerful People 2018". Forbes.

- ↑ "SA-born Elon Musk has been named the world's 25th most influential person for revolutionising transportation 'both on earth and in space'". www.businessinsider.co.za.

- ↑ "Profile: Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 7 November 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ 本報獨家探訪河南鄧州習營村. Wen Wei Po (in Chinese). 16 November 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ 與丈夫習仲勛相伴58年 齊心:這輩子無比幸福 (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. 28 April 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ Bouée, Charles-Edouard, China's Management Revolution: Spirit, Land, Energy Archived 27 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine., (Palgrave Macmillan, 15 December 2010), p. 93; via Googlebooks. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ Buckley, Chris; Tatlow, Didi Kirsten. "Cultural Revolution Shaped Xi Jinping, From Schoolboy to Survivor". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ 不忘初心:是什么造就了今天的习主席? (in Chinese). Retrieved 30 January 2018.

Liangjiahe Village Shaanxi Province

- ↑ Pierson, Barbara Demick and David (14 February 2012). "China's political star Xi Jinping is a study in contrasts". Retrieved 24 October 2017 – via Toronto Star.

- ↑ Watts, Jonathan (26 October 2007). "Most corrupt officials are from poor families but Chinese royals have a spirit that is not dominated by money". The Guardian. London, England. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ↑ Associated Press, "China's Vice-President revisits youth with a trip to the Midwest to meet farming family he stayed with on exchange trip" Archived 28 April 2012 at Archive-It, Daily Mail, 15 February 2012.

- ↑ The Street, "President Xi Slept Here: How a Trip to Iowa in 1985 Changed U.S.-China Relations" Archived 18 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Xi Jinping". 30 March 2010.

- ↑ KERRY BROWN. "Wednesday February 28, 2018 Full Text Transcript | CBC Radio". CBC.

- ↑ Ranade, Jayadva (25 October 2010). "China's Next Chairman – Xi Jinping". Centre for Air Power Studies. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ "Xi Jinping". GlobalSecurity.org. 7 November 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ 中共十五大习近平位列候补委员最后一名为何 (in Chinese). Canyu.org. 22 April 2011.

- ↑ Tiezzi, Shannon. "From Fujian, China's Xi Offers Economic Olive Branch to Taiwan" Archived 10 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine., The Diplomat, 4 November 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ Yu, Xiao (18 February 2000). "Fujian leaders face Beijing top brass". South China Morning Post.

- ↑ Ho, Louise. "Xi Jinping's time in Zhejiang: doing the business" Archived 29 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine., The South China Morning Post, 25 October 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ↑ Wang, Lei (25 December 2014). 习近平为官之道 拎着乌纱帽干事. Duowei News (in Chinese).

- ↑ 习近平任上海市委书记 韩正不再代理市委书记 (in Chinese). Sohu. 24 March 2007.

- ↑ 从上海到北京 习近平贴身秘书只有钟绍军. Mingjing News (in Chinese). Boxun. 11 July 2013.

- ↑ Lam, Willy (20 March 2015). Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping. Routledge.

- ↑ 新晋政治局常委:习近平. Caijing (in Chinese). 22 October 2007.

- ↑ "Hu Jintao reelected Chinese president" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Xinhua (China Daily), 15 March 2008.

- ↑ "Vice-President Xi Jinping to Visit DPRK, Mongolia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Yemen". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 5 June 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ Wines, Michael, 'China's Leaders See a Calendar Full of Anniversaries, and Trouble' Archived 21 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. The New York Times, 9 March 2009.

- ↑ Ansfield, Jonathan (22 December 2007). "Xi Jinping: China's New Boss And The 'L' Word". Newsweek. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ "China's Nelson Mandela". Time. 19 November 2007.

- ↑ Tang, Eugene (15 March 2008). "China Appoints Xi Vice President, Heir Apparent to Hu". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ Rudd seeks to pre-empt PM's China white paper with his own version Archived 22 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The National, David Uren, 5 October 2012

- ↑ Rauhala, Emily (28 September 2015). "Hillary Clinton called Xi's speech 'shameless,' and the Web went wild". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Chinese vice president in Mexico to boost trade". Channel NewsAsia. Agence France-Presse. 11 February 2009.

- ↑ "Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping speaks during a news conference in Mexico City. Jinping is on a two-day official visit to Mexico". Associated Press. 10 February 2009.

- ↑ "Photo Gallery of the Official Visit of the Vice President of the People's Republic of China and the State Visit of the King and Queen of Spain". Jamaica Information Service. 12 February 2009.

- ↑ "China, Jamaica vow to enhance friendly partnership". China Central Television. 13 February 2009.

- ↑ Mu Xuequan (17 February 2009). "Chinese vice president concludes official visit to Colombia". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ "China Names Colombia Official Tourism Destination". Latin American Herald Tribune.

- ↑ Fang Yang (19 February 2009). "Chinese VP meets Venezuelan top legislator on parliamentary co-op, bilateral ties". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Devereux, Charlie (26 September 2012). "China Bankrolling Chavez's Re-Election Bid With Oil Loans". Bloomberg News.

- ↑ "Chinese VP meets Brazilian president on deepening strategic partnership". Xinhua News Agency. 20 February 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ "Xi Jinping visits Malta". The Embassy of Malta in the People's Republic of China. 23 February 2009.

- ↑ Mu Xuequan (22 February 2009). "Roundup: Chinese vice president starts official visit to Malta". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Original (Chinese): simplified Chinese: 在国际金融风暴中,中国能基本解决13亿人口吃饭的问题,已经是对全人类最伟大的贡献; traditional Chinese: 在國際金融風暴中,中國能基本解決13億人口吃飯的問題,已經是對全人類最偉大的貢獻-In Chinese

- ↑ Original: simplified Chinese: 有些吃饱没事干的外国人,对我们的事情指手画脚。中国一不输出革命,二不输出饥饿和贫困,三不折腾你们,还有什么好说的?; traditional Chinese: 有些吃飽沒事干的外國人,對我們的事情指手畫腳。中國一不輸出革命,二不輸出飢餓和貧困,三不折騰你們,還有什麽好說的?

- ↑ "AsiaOne.com: Chinese VP blasts meddlesome foreigners". News.asiaone.com. 14 February 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ Lai Jinhong (賴錦宏) (18 February 2009). 習近平出訪罵老外 外交部捏冷汗 [Xi Jinping scored at foreigners, Ministry of foreign affairs had cold sweat] (in Chinese). United Daily News. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ↑ "Vice President Xi Jinping to visit Belgium, Germany, Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania and attend Europalia Chinese Art Festival and China's Guest-of-Honor Activities in Frankfurt Book Fair". Mfa.gov.cn. 10 October 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ Raman, B. (25 December 2009). "China's Cousin-Cousin Relations with Myanmar". South Asia Analysis Group. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Reuters Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ "Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping heads back to his favourite U.S. town 27 years after he first stayed there" Archived 27 July 2012 at Archive.is, Daily Mail Online, 16 February 2012

- ↑ Osnos, Evan (6 April 2012). "Born Red: How Xi Jinping, an unremarkable provincial administrator, became China's most authoritarian leader since Mao". The New Yorker.

- ↑ "The secret story behind Xi Jinping's disappearance, finally revealed?". The Washington Post. 1 November 2012.

- ↑ "China Confirms Leadership Change". BBC News. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ "Xi Jinping: China's 'princeling' new leader". Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ "Ending Congress, China Presents New Leadership Headed by Xi Jinping". The New York Times. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ "After months of mystery, China unveils new top leaders". CNN. 16 November 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ Johnson, Ian (15 November 2012). "A Promise to Tackle China's Problems, but Few Hints of a Shift in Path". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ↑ "Full text: China's new party chief Xi Jinping's speech". BBC. 15 November 2012.

- ↑ Page, Jeremy (13 March 2013). "New Beijing Leader's 'China Dream' – WSJ". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Chen, Zhuang (10 December 2012). "The symbolism of Xi Jinping's trip south". BBC News. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ↑ BBC News (2012). "China confirms leadership change" Archived 29 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine., BBC. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ↑ Demick, Barbara (3 March 2013). "China's Xi Jinping formally assumes title of president". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ "China's Xi Jinping hints at backing Sri Lanka against UN resolution". Press Trust of India. 16 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ Cheung, Tony; Ho, Jolie (17 March 2013). "CY Leung to meet Xi Jinping in Beijing and explain cross-border policies". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ "China names Xi Jinping as new president". Agence France-Presse. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ Chris Buckley, "China's Leader Tries to Calm African Fears of His Country's Economic Power" Archived 21 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine., The New York Times, 26 March 2013

- 1 2 3 Kroeber, Arthur R. (17 November 2013). "Xi Jinping's Ambitious Agenda for Economic Reform in China". The Brookings Institution. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ↑ "Top legislature amends law to allow all couples to have two children". Xinhua News Agency. 27 December 2015.

- ↑ "China formally abolishes decades-old one-child policy". International Business Times. 27 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Presidential Style: A New Flavour". The Economist. 4 January 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ "Xi Jinping's inaugural Speech". BBC News. 15 November 2012.

- ↑ "Elite in China Face Austerity Under Xi's Rule". The New York Times. 27 March 2013.

- ↑ "President Xi's Anti-Corruption Campaign Biggest Since Mao". Bloomberg. 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "2.3 The Chinese Communist Party" in: Sebastian Heilmann, editor, Archived 23 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. China's Political System, Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (2017) ISBN 978-1442277342 and ISBN 1442277343

- 1 2 Phillips, Tom (24 October 2017). "Xi Jinping becomes most powerful leader since Mao with China's change to constitution". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ↑ Associated Press (24 October 2017). "China elevates Xi to most powerful leader in decades". CBC News. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ "China elevates Xi Jinping's status, making him the most powerful leader since Mao". Independent.ie. 24 October 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ Collins, Stephen (9 November 2017). "Xi's up, Trump is down, but it may not matter". CNN. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ Holtz, Michael (28 February 2018). "Xi for life? China turns its back on collective leadership". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ↑ Keck, Zachary (7 January 2014). "Is Li Keqiang Being Marginalized?". The Diplomat.

- ↑ Meng, Chuan (4 November 2014). 习近平军中"亮剑" 新古田会议一箭多雕. Duowei News (in Chinese).

- ↑ Buckley, Chris; Myers, Steven Lee (11 October 2017). "Xi Jinping Presses Military Overhaul, and Two Generals Disappear". Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.

- ↑ "Xi Jinping named as 'commander in chief' by Chinese state media". The Guardian. 21 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Kayleigh, Lewis (23 April 2016). "Chinese President Xi Jinping named as military's 'commander-in-chief'". The Independent. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Sison, Desiree (22 April 2016). "President Xi Jinping is New Commander-in-Chief of the Military". China Topix. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ "China's Xi moves to take more direct command over military". Columbia Daily Tribune. 24 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Frenkiel, Emilie (2015). "Le président chinois le plus puissant depuis Mao Zedong" [The most powerful Chinese president since Mao Zedong]. Le monde diplomatique (in French). October 2015: 4f.

- ↑ "The power of Xi Jinping. A cult of personality is growing around China's president. What will he do with his political capital?". The Economist. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- 1 2 Phillips, Tom (2015-09-19). "Xi Jinping: Does China truly love 'Big Daddy Xi' – or fear him?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- ↑ Blanchard, Ben (28 October 2016). "All hail the mighty uncle - Chinese welcome Xi as the 'core'". Reuters. United States. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ↑ Rivers, Matt (19 March 2018). "This entire Chinese village is a shrine to Xi Jinping". CNN. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ↑ "Communist Party pledges greater role for constitution, rights in fourth plenum". South China Morning Post. 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Doyon, J; Winckler, H (20 November 2014). "The Fourth Plenum, Party Officials and Local Courts" (22).

- ↑ "Xi's maiden foreign tour historic, fruitful". People.cn. 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Bush, Richard C. III. "Obama and Xi at Sunnylands: A Good Start". Brookings Institution.

- ↑ "President Xi visits Western Europe". Xinhua News Agency. 22 March 2014.

- ↑ Korean Culture and Information Service (KOCIS). "President Xi, 'Korea-China relations better than ever'". korea.net.

- ↑ "Xi Jinping's July 2014 Trip to Latin America". Carnegie Endowment for World Peace. 5 September 2014.

- ↑ "Chinese incursion in Ladakh: A little toothache can paralyze entire body, Modi tells Xi Jinping". Time of India. 20 September 2014.

- ↑ "Xi says time to lift relations". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 November 2014.

- ↑ "Chinese president Xi Jinping signs five agreements with Fiji as part of China's Pacific engagement strategy". ABC News (Australia). 22 November 2015.

- ↑ Xi Jinping Heads to Pakistan, Bearing Billions in Infrastructure Aid Archived 9 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. 19 April 2015

- ↑ "At Russia's Military Parade, Putin and Xi Cement Ties". The Diplomat. 9 May 2015.

- ↑ Nectar Gan and Cedric Sam. "Xi Jinping's US visit: itinerary, issues and delegation". South China Morning Post.

- ↑ Xi Jinping's U.S. Visit – NYTimes.com Archived 11 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "China's President Xi Jinping begins first US visit in Seattle". The Guardian.

- ↑ "State Visit by the President of the People's Republic of China".

- ↑ "Chinese president Xi Jinping visit: United fan premier to visit Manchester City's stadium". Manchester Evening News. 23 October 2015.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-28. Czech courtship pays off with landmark visit from Chinese leader

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-28. Protests as China's Xi arrives in Prague

- ↑ de la Merced, Michael J., and Russell Goldman, "How Davos Brings the Global Elite Together", New York Times, January 14, 2017. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ↑ Wong, Edward, "As China Seeks Bigger Role on World Stage, Xi Jinping Will Go to Davos World Economic Forum" ("Click for translation/点击查看本文中文版"), New York Times, January 10, 2017. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- 1 2 China Daily, "Xi first top Chinese leader at Davos", people.cn, January 11, 2017. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ↑ "Leader Taps into Chinese Classics in Seeking to Cement Power". The New York Times. 12 October 2014.

- ↑ Mitchell, Ryan Mi. "Is 'China's Machiavelli' Now Its Most Important Political Philosopher?". The Diplomat.

- ↑ "End to term limits at top 'may be start of global backlash for China'". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ↑ Phillips, Tom (2018-03-04). "Xi Jinping's power play: from president to China's new dictator?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- ↑ "China's parliament re-elects Xi Jinping as president". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ Bodeen, Christopher. "Xi reappointed as China's president with no term limits". Associated Press. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Li Keqiang endorsed as China's premier; military leaders confirmed". scmp.com.

- ↑ "China's foreign minister gains power in new post as state councillor". scmp.com.

- ↑ Mitchell, Tom. "China's Xi Jinping says he is opposed to life-long rule". Financial Times. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

President insists term extension is necessary to align government and party posts

- ↑ Fallows, James (3 May 2013). "Today's China Notes: Dreams, Obstacles". The Atlantic.

- ↑ "The role of Thomas Friedman". The Economist. 6 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Chasing the Chinese dream" Archived 28 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine., The Economist 4 May 2013, pp. 24–26

- ↑ Chinese: 中华民族伟大复兴, which can also be translated as the "Great Renaissance of the Chinese nation" or the "Great revival of the Chinese people".

- ↑ "Xi Jinping and the Chinese Dream" Archived 10 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine., The Economist 4 May 2013, p 11 (editorial)

- ↑ 中共中央政治局召开会议 研究拟提请党的十八届七中全会讨论的文件-新华网. news.xinhuanet.com (in Chinese). Retrieved 2017-10-04.

- ↑ "CCP Constitution Amendment May Signal Xi's Power - China Digital Times (CDT)". China Digital Times (CDT). 2017-09-19. Retrieved 2017-10-04.

- 1 2 Zhang, Ling (18 October 2017). "CPC creates Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era". Xinhua. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ↑ "Xi presents new CPC central leadership, roadmap for next 5 years". Xinhua. 24 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ↑ "Second volume of Xi's book on governance published - Xinhua | English.news.cn". news.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ↑ Meng, Angela (6 September 2014). "Xi Jinping rules out Western-style political reform for China". South China Morning Post.

- 1 2 Li, Cheng (26 September 2014). "A New Type of Major Power Relationship?". The Brookings Institution (Interview).

- ↑ Osawa, Jun (17 December 2013). "China's ADIZ over the East China Sea: A "Great Wall in the Sky"?". Brookings Institution.

- 1 2 HIROYUKI, AKITA (22 July 2014). "A new kind of 'great power relationship'? No thanks, Obama subtly tells China". Nikkei Asian Review.

- ↑ Ng, Teddy; Kwong, Man-ki (9 July 2014). "President Xi Jinping warns of disaster if Sino-US relations sour". South China Morning Post.

- ↑ Correspondent, Evan Perez, CNN Justice. "FBI arrests Chinese national connected to malware used in OPM data breach". CNN.

- ↑ "Hacks of OPM databases compromised 22.1 million people, federal authorities say". The Washington Post. July 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Baker, Peter (8 November 2014). "As Russia Draws Closer to China, U.S. Faces a New Challenge". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Just what is this One Belt, One Road thing anyway?". CNN.

- ↑ "Xi proposes a 'new Silk Road' with Central Asia". China Daily.

- ↑ Blanchard, Ben (3 July 2014). "With one eye on Washington, China plots its own Asia 'pivot'". Reuters.

- ↑ "Asian nations should avoid military ties with third party powers, says China's Xi". China National News. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Miller, Matthew. "China's Xi tones down foreign policy rhetoric". CNBC. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ↑ "Pakistan confers Nishan-e-Pakistan on Chinese president Xi Jinping". Hindustan Times. 21 April 2015.

- ↑ "China building runway in disputed South China Sea island". BBC. 17 April 2015.

- ↑ "Defense secretary's warning to China: U.S. military won't change operations". The Washington Post. 27 May 2015.

- ↑ President Xi: Build the B&R into a road for peace, prosperity and connectivity, CGTN (China's 24-hour English language television channel)

- ↑ Forde, Brendan (9 September 2013). "China's 'Mass Line' Campaign". The Diplomat. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ↑ Levin, Dan (20 December 2013). "China Revives Mao-Era Self-Criticism, but This Kind Bruises Few Egos". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ↑ Tiezzi, Shannon (27 December 2013). "The Mass Line Campaign in the 21st Century". The Diplomat. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ↑ AFP, above, quoting Joseph Cheng of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- ↑ Veg, Sebastien (11 August 2014). "China's Political Spectrum under Xi Jinping". The Diplomat.

- ↑ 省储备局认真学习贯彻落实《关于当前意识形态领域情况的通报》,湖南机关党建,2013年05月16日 Archived 15 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 西藏广电局召开传达学习有关文件精神会议,中国西藏之声网,2013-05-09 Archived 15 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 2288. 当前我国意识形态建设面临的六大挑战--理论--人民网. People's Daily (in Chinese).

- 1 2 "China's New Leadership Takes Hard Line in Secret Memo" Archived 21 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine. article by Christopher Buckley in The New York Times 19 August 2013

- ↑ Raymond Li (29 August 2013). "Seven subjects off limits for teaching, Chinese universities told: Civil rights, press freedom and party's mistakes among subjects banned from teaching in order described by an academic as back-pedalling". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Denyer, Simon (2017-10-25). "China's Xi Jinping unveils his top party leaders, with no successor in sight". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ↑ 2018-04-21 21:48:46. "Xinhua Headlines: Xi outlines blueprint to develop China's strength in cyberspace - Xinhua | English.news.cn". Xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ↑ Risen, Tom (3 June 2014). "Tiananmen Censorship Reflects Crackdown Under Xi Jinping". US News.

- ↑ "Chinese dream turns sour for activists under Xi Jinping". Agence France-Presse. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ Phillips, Tom (6 August 2015). "'It's getting worse': China's liberal academics fear growing censorship". The Guardian.