Lily-white movement

| Part of a series of articles on |

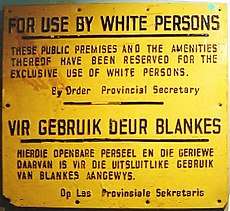

| Racial segregation |

|---|

|

| Germany |

| South Africa |

| United States |

| African-American topics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

|

Civic / economic groups |

|||

|

Sports

|

|||

|

Ethnic subdivisions |

|||

|

Languages |

|||

|

Diaspora |

|||

| |||

The Lily-White Movement was an anti-civil-rights movement within the Republican Party in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement was a response to the political and socioeconomic gains made by African-Americans following the Civil War and the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which eliminated slavery.

During Reconstruction, following the U.S. Civil War, black leaders in Texas and around the country gained increasing influence in the Republican Party by organizing blacks as an important voting bloc via Union Leagues and the biracial Black-and-tan faction of the Republicans.. Conservative whites attempted to eliminate this influence and recover white voters who had defected to the Democratic Party. The effort was largely successful in eliminating African-American influence in the Republican Party leading to black voters predominantly migrating to the Democratic Party for much of the 20th century.

The term lily-white movement was coined by Texas Republican leader Norris Wright Cuney, who used the term in an 1888 Republican convention to describe efforts by white conservatives to oust blacks from positions of Texas party leadership and incite riots to divide the party.[1] The term came to be used nationally to describe this ongoing movement as it further developed in the early 20th century,[2] including through the administration of Herbert Hoover. Localized movements began immediately after the war but by the beginning of the 20th century the effort had become national.

According to author and professor Michael K. Fauntroy, "the 'Lily-White Movement' is one of the darkest, and under-examined [sic], eras of American Republicanism."[3][4]

Background

Immediately following the war all of the Southern states enacted "Black Codes," laws intended specifically to curtail the rights of the newly freed slaves. Many Northern states enacted their own "Black Codes" restricting or barring black immigration.[5] The Civil Rights Act of 1866, however, nullified most of these laws and the federal Freedman's Bureau was able to regulate many of the affairs of Southern blacks, who were granted the right to vote in 1867. Groups such as the Union League and the Radical Republicans sought total equality and complete integration of blacks into American society. The Republican Party itself held significant power in the South during Reconstruction because of the federal government's role.[6]

During Reconstruction, Union Leagues were formed across the South after 1867 as all-black working auxiliaries of the Republican Party. They were secret organizations that mobilized freedmen to register to vote and to vote Republican. They discussed political issues, promoted civic projects, and mobilized workers opposed to certain employers. Most branches were segregated but there were a few that were racially integrated. The leaders of the all-black units were mostly urban blacks from the North, who had never been slaves. Historian Eric Foner reports:[7]

By the end of 1867 it seemed that virtually every black voter in the South had enrolled in the Union League, the Loyal League, or some equivalent local political organization. Meetings were generally held in a black church or school.

— Eric Foner, Black Leaders of the Nineteenth Century

During the 19th century numerous African Americans were elected to the United States Congress, all members of the Republican Party. In the South the party was a voting coalition of Freedmen (freed slaves), Carpetbaggers (recent arrivals from the North), and Scalawags (Southern whites, especially men who had been Unionists in the War). In Texas, blacks comprised 90% of the party members during the 1880s.[8] The first black senator was Hiram Rhodes Revels of Mississippi. The first black representative was John Willis Menard of Louisiana. Over the course of the century, an additional black senator (from Mississippi) would be elected and more than 20 black representatives would be elected from Louisiana, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, North Carolina, and Virginia.

Blacks held other powerful political positions in government. P. B. S. Pinchback was elected lieutenant governor of Louisiana and even served briefly as governor. Pierre Caliste Landry became mayor of Donaldsonville, Louisiana. Edward Duplex became mayor of Wheatland, California.

In the South the Republican party gradually came to be known as "the party of the Negro."[9] In Texas, for example, blacks made 90% of the party during the 1880s.[10] The Democratic party increasingly came to be seen by many in the white community as the party of respectability.[9] The first Ku Klux Klan targeted violence against black Republican leaders and seriously undercut the Union League.[11]

In the 1870s through early 1890s, Democrats in Southern states used various methods to suppress the vote of blacks, largely intimidation, violence and fraud. Republicans responded by challenging the election results and overturning them in order to count the votes of blacks. This was much more successful when Republicans held an uncontested majority of the US House than otherwise.

Republican factionalism

From the beginning of Reconstruction, conservative Southern white factions fought against the black-and-tan faction, coalitions of blacks and liberal whites, for control of the Republican Party. White Republican leaders became increasingly concerned about the exodus of white voters in other parts of the country, some out of concerns for the strength of the party and some for purely racist reasons, thus giving impetus to what would be called the lily-white movement.

Blacks increasingly demanded more and more offices at the expense of the Scalawags. The more numerous black-and-tan element typically won the factional battles; many Scalawags joined the opposing lily-whites or switched to the Democrats.[12][13] The black-and-tans predominated in counties with large black populations, as the whites in these counties were usually Democrats, whereas the lily-whites were found mostly in the counties where fewer blacks lived.

Following the death of Texas Republican leader Edmund J. Davis in 1883, black civil rights leader Norris Wright Cuney rose to the Republican chairmanship in Texas, becoming the national committeeman in 1889.[14] While blacks were a minority overall in Texas, Cuney's rise to this position caused a backlash among white conservative Republicans in other areas, leading to the lily-white's becoming a more organized, nationwide effort. Cuney himself coined the term lily-white movement to describe rapidly intensifying organized efforts by white conservatives to oust blacks from positions of party leadership and incite riots to divide the party.[15] Some authors contend that the effort was coordinated with Democrats as part of a larger movement toward disenfranchisement of blacks in the South by increasing restrictions in voter registration rules.[16]

Black disfranchisement in Southern states

By 1890 the Democratic Party had gained control of all state legislatures in the South (with a few brief exceptions as in North Carolina). By the beginning of the 20th century black political influence was in freefall. From 1890 to 1908, Southern states accomplished disenfranchisement of blacks and, in some states, many poor whites.[17] During the first three decades of the 20th century blacks were excluded from the U.S. Congress.[18]

By the 1890s most blacks had abandoned or were prevented from seeking office in the U.S. Congress.[6] The last five African Americans that served in Congress, all college-educated, were the product of Reconstruction era educational and economic opportunities which were significantly eroded in the early 20th century.[19] The last black Congressman of this earlier era departed the Congress in 1901. Blacks still had some influence in the Republican party but their influence continued to decline rapidly.

Downfall of black Republicans

By the beginning of the 20th century, black political influence was in freefall, both because the Republican lily-white movement and the efforts by the Democratic Southern governments. During the first three decades of the 20th century, no blacks served in the U.S. Congress due to their disenfranchisement across the South.[20] By the 1920s, the lily-white movement had largely succeeded in establishing almost total white supremacy in the party. Black leaders were barred in 1922 from the Virginia Republican Congressional Convention. The state had imposed racial segregation of public places and disenfranchised most blacks by this time.[21]

At a national level, the Republican Party made some attempts to respond to black interests.[22][23] The party proposed federal legislation to prohibit lynching, which was always defeated by the Southern bloc. In 1920 Republicans made opposition to lynching part of their platform at the Republican National Convention. Lynchings, primarily of black men in the South, had increased in the decades around the turn of the 20th century. Leonidas C. Dyer, a white Republican Representative from St. Louis, Missouri, worked with the NAACP to introduce an anti-lynching bill into the House, where he gained strong passage in 1922.[24] One of the Black and Tan partisans who continued to hold appointed office was Walter L. Cohen of New Orleans, the customs inspector and later comptroller of customs. He gained appointments from four Republican presidents and continued in office through the Calvin Coolidge administration.[25]

During the NAACP national convention in 1926, the delegates expressed their disappointment with the party:[26]

Our political salvation and our social survival lie in our absolute independence of party allegiance in politics and the casting of our vote for our friends and against our enemies whoever they may be and whatever party labels they carry.

— NAACP, 1926 Convention

An interesting historical irony is that, though strengthening the Republican Party in the South was a major motivation of the movement, the party faded to near irrelevance in the South during the early 20th century despite the movement's success.

Aftermath

Lily-white/black-and-tan factionalism flared up in 1928,[27] when Herbert Hoover tried to appeal to southern whites; and 1952.[28] The surviving Black-and-tan factions lost heavily in 1964 and practically vanished. Due to Democratic support of the civil rights movement and Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the shift of African Americans toward Democratic candidates accelerated.[29]

Important figures

- Lily-white leaders

- Herbert Hoover, Republican President between 1929 and 1933. He had alliances with black leaders, but broke with them in 1928 to gain Lily-white support in the South.[30]

- James P. Newcomb, Republican Secretary of State of Texas between 1870 and 1874, journalist, and longtime influential Texas party leader.[31]

- Jeter C. Pritchard, Republican U.S. Senator from western North Carolina between 1895 and 1903. He was a leading figure in the lily-white movement.[32]

- William Howard Taft, Republican President between 1909 and 1913, who sought to expand Republican appeal in the South by eliminating black involvement.[1]

- Leading opponents

- Norris Wright Cuney, Texas Republican Party chairman

- Booker T. Washington, president of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama; he had close ties to leading Republicans and was a force in black politics.[33]

See also

References

- 1 2 Myrdal (1996), pg. 478

- ↑ "NEGROES LOSE FIGHT IN NORTH CAROLINA; Pritchard's "Lilly Whites" Recognized by the President. Politicians in Washington Are Puzzled by Contradictory Aspects of Mr. Roosevelt's Policy in the South". New York Times. 17 February 1903.

- ↑ Michael K. Fauntroy (4 January 2007). "Republicans and the Black Vote". The Huffington Post.

- ↑ Michael K. Fauntroy (2007). Republicans and the Black Vote. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 164.

- ↑ "African American History". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- 1 2 Brady (2008), pg. 154

- ↑ Leon F. Litwack and August Meier, eds. (1991). Black Leaders of the Nineteenth Century. p. 221.

- ↑ Lily-white movement from the Handbook of Texas Online

- 1 2 Masson, David; Masson, George; Morley, John; Morris, Mowbray Walter (1900). "The Future of the Negro". Macmillan's magazine: 449.

- ↑ Lily-white movement from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ↑ Steven Hahn, A nation under our feet: Black political struggles in the rural South, from slavery to the great migration (2003). pp 165-205

- ↑ Sarah Woolfolk Wiggins, The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865-1881 (University of Alabama Press, 1977).

- ↑ Frank J. Wetta, The Louisiana Scalawags: Politics, Race, and Terrorism during the Civil War and Reconstruction (2012)

- ↑ Lily-white movement from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ↑ Myrdal, Gunnar; Bok, Sissela (1944). An American dilemma: the Negro problem and modern democracy. p. 478.

- ↑ Fauntroy, Michael K. (2007). Republicans and the Black Vote. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 43.

... lily whites worked with Democrats to disenfranchise African Americans.

- ↑ Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908 (2001)

- ↑ "The Negroes' Temporary Farewell: Jim Crow and the Exclusion of African Americans from Congress, 1887–1929". Black Americans in Congress (House of Representatives). Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ↑ Brady (2008), pg. 155

- ↑ "The Negroes' Temporary Farewell: Jim Crow and the Exclusion of African Americans from Congress, 1887–1929". Black Americans in Congress (House of Representatives). Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ↑ "Virginia Party Politics". Virginia Center for Digital History (University of Virginia). Retrieved 9 October 2009.

"NEGROES AGAIN BARRED FROM G.O.P. CONVENTION". Daily Progress. July 23, 1922. - ↑ Lewis L. Gould, The Republicans: A History of the Grand Old Party (2014)

- ↑ Vincent P. De Santis, Republicans face the southern question: The new departure years, 1877-1897 (1959).

- ↑ George C. Rable, "The South and the Politics of Antilynching Legislation, 1920-1940." Journal of Southern History 51.2 (1985): 201-220. in JSTOR

- ↑ Louisiana Historical Association. "A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography". lahistory.org. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ Wasniewski, Matthew ; Office of History and Preservation House (2008). Black Americans in Congress, 1870-2007. Government Printing Office. p. 183.

- ↑ Lisio, Donald J. (2012). Hoover, Blacks, and Lily-Whites: A Study of Southern Strategies. U North Carolina Press. p. 37ff.

- ↑ Marty Cohen; et al. (2009). The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform. p. 118.

- ↑ Robert David Johnson (2009). All the Way with LBJ: The 1964 Presidential Election. p. 84.

- ↑ Donald J. Lisio, Hoover, Blacks, & Lily-Whites: A Study of Southern Strategies (1985)

- ↑ Hales (2003), pg. 40

- ↑ Spragens (1988), pg. 196-198

- ↑ Kevern J. Verney, The Art of the Possible: Booker T. Washington and Black Leadership in the United States, 1881-1925 (2013).

citation 1 incomplete. what is Myrdal 1996? no such citation exists.

Further reading

- Abbott, Richard H. The Republican Party and the South, 1855–1877 (University of North Carolina Press, 1986),

- Lily-white movement from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Brady, Robert A. (2008). Black Americans in Congress, 1870-2007 (House Document No. 108-224). U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Casdorph, Paul D. Republicans, Negroes, and Progressives in the South, 1912-1916 (University of Alabama Press, 1981). online

- Fauntroy, Michael K. (2007). Republicans and the Black vote. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1-58826-470-X.

- Hales, Douglas (2003). "3: Political Education, 1869-83". A southern family in white & Black: the Cuneys of Texas. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-200-3.

- Heersink, Boris, and Jeffery A. Jenkins. "Southern Delegates and Republican National Convention Politics, 1880–1928." Studies in American Political Development 29#1 (2015): 68-88. online

- Hume, Richard L. and Jerry B. Gough. Blacks, Carpetbaggers, and Scalawags: The Constitutional Conventions of Radical Reconstruction (LSU Press, 2008); statistical classification of delegates.

- Jenkins, Jeffery A., and Boris Heersink. "Republican Party Politics and the American South: From Reconstruction to Redemption, 1865-1880." (2016 paper t the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association); online.

- Lisio, Donald J. Hoover, Blacks, & Lily-Whites: A Study of Southern Strategies (1985) online

- Myrdal, Gunnar; Bok, Sissela (1944). An American dilemma: the Negro problem and modern democracy. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-856-3.

- Spragen, William C. (1988). "8: Theodore Roosevelt". Popular images of American presidents. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Trelease, Allen W. "Who were the Scalawags?." Journal of Southern History 29.4 (1963): 445-468. in JSTOR

- Valelly, Richard M. The two reconstructions: The struggle for black enfranchisement (U of Chicago Press, 2009).

- Walton, Hanes. Black Republicans: The politics of the black and tans (Scarecrow Press, 1975).

- Ward, Judson C. "The Republican Party in Bourbon Georgia, 1872-1890." Journal of Southern History 9.2 (1943): 196-209. in JSTOR

- Watts, Eugene J. "Black Political Progress in Atlanta: 1868-1895," Journal of Negro History (1974) 59#3 pp. 268–286 in JSTOR

- Wetta, Frank J. The Louisiana Scalawags: Politics, Race, and Terrorism during the Civil War and Reconstruction (2012) online review

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk. The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865–1881 (U of Alabama Press, 1977).

Primary sources

- Link, Arthur S. "Correspondence Relating to the Progressive Party's 'Lily White' Policy in 1912." Journal of Southern History 10.4 (1944): 480-490. in JSTOR