Military history of African Americans

The military history of African Americans spans from the arrival of the first enslaved Africans during the colonial history of the United States to the present day. In every war fought by or within the United States, African-Americans participated, including the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the Civil War, the Spanish–American War, the World Wars, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as well as other minor conflicts.

Revolutionary War

| African-American topics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

|

Civic / economic groups |

|||

|

Sports

|

|||

|

Ethnic subdivisions |

|||

|

Languages |

|||

|

Diaspora |

|||

| |||

African-Americans as slaves and free blacks served on both sides during the war. Gary Nash reports that recent research concludes there were about 9000 black Patriot soldiers, counting the Continental Army and Navy, and state militia units, as well as privateers, wagoneers in the Army, servants to officers, and spies.[1] Ray Raphael notes that while thousands did join the Loyalist cause, "A far larger number, free as well as slave, tried to further their interests by siding with the patriots."[2]

Black soldiers served in Northern militias from the outset, but this was forbidden in the South, where slave-owners feared arming slaves. Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, issued an emancipation proclamation in November 1775, promising freedom to runaway slaves who fought for the British; Sir Henry Clinton issued a similar edict in New York in 1779.[3] Over 100,000 slaves escaped to the British lines, although possibly as few as 1,000 served under arms. Many of the rest served as orderlies, mechanics, laborers, servants, scouts and guides, although more than half died in smallpox epidemics that swept the British forces, and many were driven out of the British lines when food ran low. Despite Dunmore's promises, the majority were not given their freedom. Many Black Loyalists' descendants now live in Canada and Sierra Leone. Many of the Black Loyalists performed military service in the British Army, particularly as part of the only Black regiment of the war, the Black Pioneers, and others served non-military roles.

In response, and because of manpower shortages, Washington lifted the ban on black enlistment in the Continental Army in January 1776. All-black units were formed in Rhode Island and Massachusetts; many were slaves promised freedom for serving in lieu of their masters; another all-African-American unit came from Haiti with French forces. At least 5,000 African-American soldiers fought as Revolutionaries, and at least 20,000 served with the British.

Peter Salem and Salem Poor are the most noted of the African-American Patriots during this era, and Colonel Tye was perhaps the most noteworthy Black Loyalist.

Black volunteers also served with various of the South Carolina guerrilla units, including that of the "Swamp Fox", Francis Marion,[4] half of whose force sometimes consisted of free Blacks. These Black troops made a critical difference in the fighting in the swamps, and kept Marion's guerrillas effective even when many of his White troops were down with malaria or yellow fever.

The first black American to fight in the Marines was John Martin, also known as Keto, the slave of a Delaware man, recruited in April 1776 without his owner's permission by Captain of the Marines Miles Pennington of the Continental brig USS Reprisal. Martin served with the Marine platoon on the Reprisal for a year and a half and took part in many ship-to-ship battles including boardings with hand-to-hand combat, but he was lost with the rest of his unit when the brig sank in October 1777.[5] At least 12 other black men served with various American Marine units in 1776–1777; more may have been in service but not identified as blacks in the records. However, in 1798 when the United States Marine Corps (USMC) was officially re-instituted, Secretary of War James McHenry specified in its rules: "No Negro, Mulatto or Indian to be enlisted".[5] Marine Commandant William Ward Burrows instructed his recruiters regarding USMC racial policy, "You can make use of Blacks and Mulattoes while you recruit, but you cannot enlist them."[5] This policy was in line with long-standing British naval practice which set a higher standard of unit cohesion for Marines, the unit to be made up of only one race, so that the members would remain loyal, maintain shipboard discipline and help put down mutinies.[5] The USMC maintained this policy until 1942.[6][7]

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, about one-quarter of the personnel in the American naval squadrons of the Battle of Lake Erie were black, and portrait renderings of the battle on the wall of the nation's Capitol and the rotunda of Ohio's Capitol show that blacks played a significant role in it. Hannibal Collins, a freed slave and Oliver Hazard Perry's personal servant, is thought to be the oarsman in William Henry Powell's Battle of Lake Erie.[9] Collins earned his freedom as a veteran of the Revolutionary War, having fought in the Battle of Rhode Island. He accompanied Perry for the rest of Perry's naval career, and was with him at Perry's death in Trinidad in 1819.[10]

No legal restrictions regarding the enlistment of blacks were placed on the Navy because of its chronic shortage of manpower. The law of 1792, which generally prohibited enlistment of blacks in the Army became the United States Army's official policy until 1862. The only exception to this Army policy was Louisiana, which gained an exemption at the time of its purchase through a treaty provision, which allowed it to opt out of the operation of any law, which ran counter to its traditions and customs. Louisiana permitted the existence of separate black militia units which drew its enlistees from freed blacks.

A militia unit, The Louisiana Battalion of Free Men of Color, and a unit of black soldiers from Santo Domingo offered their services and were accepted by General Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans, a victory that was achieved after the war was officially over.[11]

Blacks fought at the Battle of Bladensburg 24 August 1814, many as members of Commodore Joshua Barney's naval flotilla force. This force provided crucial artillery support during the battle. One of the best accounts is that Charles Ball born 1785. Ball served with Commodore Joshua at the Battle of Bladensburg and later helped man the defenses at Baltimore. In his 1837 memoir, Ball reflected on the Battle of Bladensburg: “I stood at my gun, until the Commodore was shot down… if the militia regiments, that lay upon our right and left, cold have been brought to charge the British, in close fight, as they crossed the bridge, we should have killed or taken the whole of them in a short time; but the militia ran like sheep chased by dogs.” [12] Barney’s flotilla group included numerous African Americans who provided artillery support during the battle. Modern scholars estimate blacks made up between 15 -20 %, of the American naval forces in the War of 1812.[13]

Just before the battle Commodore Barney on being asked by President James Madison “if his negroes would not run on the approach of the British?” replied: “No Sir…they don’t know how to run; they will die by their guns first.” [14] The Commodore was correct, the men did not run, one such man was young sailor Harry Jones (no.35), apparently a free black. Harry Jones was wounded in the final action at Bladensburg. Due to the severity of Jones wounds, he remained a patient at the Naval Hospital Washington DC for nearly two months. [15]

African Americans also served with the British. On 2 April 1814, Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane issued a proclamation to all persons wishing to emigrate, similar to the aforementioned Dunmore's Proclamantion some 40 years previous. Any persons would be received by the British, either at a military outpost or aboard British ships; those seeking sanctuary could enter His Majesty's forces, or go "as free settlers to the British possessions in North America or the West Indies".[16][17] [18]Among those who went to the British, some joined the Corps of Colonial Marines, an auxiliary unit of marine infantry, embodied on 14 May 1814. British commanders later stated the new marines fought well at Bladensburg and confirm that two companies took part in the burning of Washington including the White House. Following the Treaty of Ghent, the British kept their promise and in 1815 evacuated the Colonial Marines and their families to Halifax Canada and Bermuda. [19]

Mexican–American War

A number of African Americans in the Army during the Mexican–American War were servants of the officers who received government compensation for the services of their servants or slaves. Also, soldiers from the Louisiana Battalion of Free Men of Color participated in this war. African Americans also served on a number of naval vessels during the Mexican–American War, including the USS Treasure, and the USS Columbus.[11]

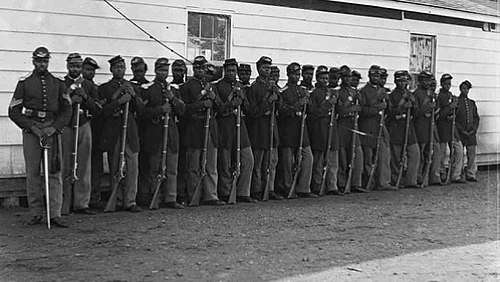

American Civil War

The history of African Americans in the U.S. Civil War is marked by 186,097 (7,122 officers, 178,975 enlisted)[20] African-American men, comprising 163 units, who served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and many more African Americans served in the Union Navy. Both free African Americans and runaway slaves joined the fight.

On the Confederate side, blacks, both free and slave, were used for labor. In the final months of the war, the Confederate Army was desperate for additional soldiers so the Confederate Congress voted to recruit black troops for combat; they were to be promised their freedom. Units were in training when the war ended, and none served in combat.[21]

Indian Wars

From 1863 to the early 20th century, African-American units were utilized by the Army to combat the Native Americans during the Indian Wars.[22] The most noted among this group were the Buffalo Soldiers:

At the end of the U.S. Civil War the army reorganized and authorized the formation of two regiments of black cavalry (the 9th and 10th US Cavalry). Four regiments of infantry (the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st US Infantry) were formed at the same time. In 1869, the four infantry regiments were merged into two new ones (the 24th and 25th US Infantry). These units were composed of black enlisted men commanded by white officers such as Benjamin Grierson, and occasionally, an African-American officer such as Henry O. Flipper. The "Buffalo Soldiers" served a variety of roles along the frontier from building roads to guarding the U.S. mail.[23]

These regiments served at a variety of posts in the southwest United States and Great Plains regions. During this period they participated in most of the military campaigns in these areas and earned a distinguished record. Thirteen enlisted men and six officers from these four regiments earned the Medal of Honor during the Indian Wars.[24]

Spanish–American War

_(14783599362).jpg)

After the Indian Wars ended in the 1890s, the regiments continued to serve and participated in the Spanish–American War (including the Battle of San Juan Hill), where five more Medals of Honor were earned.[25] They took part in the 1916 Punitive Expedition into Mexico and in the Philippine–American War.

Units

In addition to the African Americans who served in regular army units during the Spanish–American War, five African-American Volunteer Army units and seven African-American National Guard units served.

Volunteer Army:

- 7th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 8th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 9th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 10th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 11th United States Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

National Guard:

- 3rd Alabama Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 8th Illinois Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)[26]

- Companies A and B, 1st Indiana Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 23rd Kansas Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 3rd North Carolina Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 9th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

- 6th Virginia Volunteer Infantry (Colored Troops)

Of these units, only the 9th U.S., 8th Illinois, and 23rd Kansas served outside the United States during the war. All three units served in Cuba and suffered no losses to combat.

Philippine-American War

After the Treaty of Paris, the islands of the Philippines became a colony of the United States. When the U.S. military started to send soldiers into the islands, native rebels, who had already been fighting their former Spanish rulers, opposed U.S. colonization and retaliated, causing an insurrection. In what would be known as the Philippine-American War, the U.S. military also sent colored regiments and units to stop the insurrection. However, due to the discrimination of African-American soldiers, some of them defected to the Philippine Army.

One of those that defected was David Fagen, who was given the rank of captain in the Philippine Army. Fagen served in the 24th Regiment of the U.S. Army, but on November 17, 1899,[27] he defected to the Filipino army.[28] He became a successful guerrilla leader and his capture became an obsession to the U.S. military and American public. His defection was likely the result of differential treatment by American occupational forces toward black soldiers, as well as common American forces derogatory treatment and views of the Filipino occupational resistance, who were frequently referred to as "niggers" and "gugus".[29]

After two other black deserters were captured and executed, President Theodore Roosevelt announced he would stop executing captured deserters.[30] As the war ended, the US gave amnesties to most of their opponents. A substantial reward was offered for Fagen, who was considered a traitor. There are two conflicting versions of his fate: one is that his was the partially decomposed head for which the reward was claimed, the other is that he took a local wife and lived peacefully in the mountains.[31]

World War I

The U.S. armed forces remained segregated through World War I. Still, many African Americans eagerly volunteered to join the Allied cause following America's entry into the war. By the time of the armistice with Germany on November 11, 1918, over 350,000 African Americans had served with the American Expeditionary Force on the Western Front.[32]

Most African-American units were largely relegated to support roles and did not see combat. Still, African Americans played a notable role in America's war effort. For example, the 369th Infantry Regiment, known as the "Harlem Hellfighters", was assigned to the French Army and served on the front lines for six months. 171 members of the 369th were awarded the Legion of Merit.

Corporal Freddie Stowers of the 371st Infantry Regiment that was seconded to the 157th French Army division called the Red Hand Division in need of reinforcement under the command of the General Mariano Goybet was posthumously awarded a Medal of Honor[33]—the only African American to be so honored for actions in World War I. During action in France, Stowers had led an assault on German trenches, continuing to lead and encourage his men even after being twice wounded. Stowers died from his wounds, but his men continued the fight and eventually defeated the German troops. Stowers was recommended for the Medal of Honor shortly after his death, but the nomination was, according to the Army, misplaced. In 1990, under pressure from Congress, the Department of the Army launched an investigation. Based on findings from this investigation, the Army Decorations Board approved the award of the Medal of Honor to Stowers. On April 24, 1991–73 years after he was killed in action—Stowers' two surviving sisters received the Medal of Honor from President George H. W. Bush at the White House. The success of the investigation leading to Stowers' Medal of Honor later sparked a similar review that resulted in six African Americans being posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in World War II. Vernon Baker was the only recipient who was still alive to receive his award.[34]

Units

Some of the most notable African-American units which served in World War I were:

_Troops_on_the_Deck_of_the_%22Louisville.%22_Part_of_the_Squadr_._._._-_NARA_-_533486.tif.jpg)

- 92nd Infantry Division[35]

- 93rd Infantry Division

- 369th Infantry Regiment ("Harlem Hellfighters"; formerly the 15th New York National Guard)

- 370th Infantry Regiment (formerly the 8th Illinois)[36][37]

- 371st Infantry Regiment

- 372nd Infantry Regiment

Support units included:

- Butchery Companies, Nos. 322 and 363

- Stevedore Regiments, Nos. 301, 302 and 303d Stevedore Regiment and Stevedore Battalions, Nos. 701, 702

- Engineer Service Battalions, Nos. 505 to 550, inclusive

- Labor Battalions, Nos. 304 to 315, inclusive; Nos. 317 to 327, inclusive ; Nos. 329 to 348, inclusive, and No. 357

- Labor Companies, Nos. 301 to 324, inclusive

- Pioneer Infantry Battalions, Nos. 801 to 809, inclusive; No. 811 and Nos. 813 to 816, inclusive.[38]

A complete list of African-American units that served in the war is published in the book Willing Patriots: Men of Color in World War One. The book is cited in the "Further reading" section of this article.

Period between the world wars

Even though the U.S. government was nominally neutral in the wars waged by Fascists against Ethiopia and Fascists and Nazis against the Spanish Republic in the mid-1930s, African Americans found it hard to be neutral and many became Antifascist.[39]

Second Italo-Abyssinian War

On October 4, 1935, Fascist Italy invaded Ethiopia. Being the only non-colonized African country besides Liberia, the invasion of Ethiopia caused a profound response amongst African Americans.[40] African Americans organized to raise money for medical supplies, and many volunteered to fight for the African kingdom.[41] Within eight months, however, Ethiopia was overpowered by the advanced weaponry and mustard gas of the Italian forces.

Many years later Haile Selassie I would comment on the efforts: "We can never forget the help Ethiopia received from Negro Americans during the crisis. ... It moved me to know that Americans of African descent did not abandon their embattled brothers, but stood by us."[41]

Spanish Civil War

When General Franco rebelled against the newly established secular Spanish Republic, a number of African Americans volunteered to fight for Republican Spain. Many African Americans who were in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade had Communist ideals. Among these, there was Vaughn Love who went to fight for the Spanish loyalist cause because he considered Fascism to be the "enemy of all black aspirations."

African-American activist and World War I veteran Oliver Law, fighting in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War, is believed to have been the first African-American officer to command an integrated unit of soldiers.[42]

James Peck was an African-American man from Pennsylvania who was turned down when he applied to become a military pilot in the US. He then went on to serve in the Spanish Republican Air Force until 1938.[43] Peck was credited with shooting down five Aviación Nacional planes, two Heinkel He-51s from the Legion Condor and three Fiat CR.32 Fascist Italian fighters.

Salaria Kea was a young African-American nurse from Harlem Hospital who served as a military nurse with the American Medical Bureau in the Spanish Civil War. She was one of the two only African-American female volunteers in the midst of the war-torn Spanish Republican areas.[44] When Salaria came back from Spain she wrote the pamphlet "A Negro Nurse in Spain" and tried to raise funds for the beleaguered Spanish Republic.[45]

World War II

The Pittsburgh Courier[46]

Despite a high enlistment rate in the U.S. Army, African Americans were not treated equally. At parades, church services, in transportation and canteens the races were kept separate. The Women's Army Corps (WAC) changed its enlistment policies in January 1941, allowing for African-American women to join the ranks of Army nurses to strengthen the war effort. Much like with male soldiers, Black women were given separate training, inferior living quarters, and rations. Black nurses were integrated into everyday life with their white colleagues and often felt the pain of discrimination and slander from the wounded soldiers they cared for and the leadership assigned to them.[47]

Elizabeth "Tex" Williams served in the Women's Army Corps as an African American military photographer from 1944 to 1970. According to scholars, she was one of the few successful women photographers in her time.[48]

The Navy did not follow suit in changing its policies to include women of color until January 25, 1945. The first African-American woman sworn into the Navy was Phyllis Mae Dailey, a nurse and Columbia University student from New York. She was the first of only four African-American women to serve in the navy during World War II.[49]

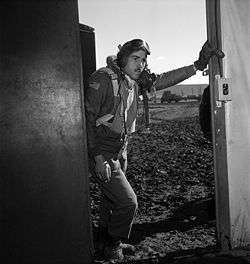

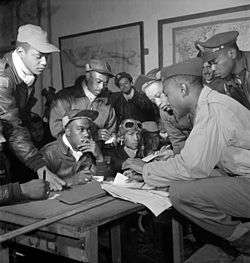

Many soldiers of color served their country with distinction during World War II. There were 125,000 African Americans who were overseas in World War II. Famous segregated units, such as the Tuskegee Airmen and 761st Tank Battalion and the lesser-known but equally distinguished 452nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion,[50] proved their value in combat, leading to desegregation of all U.S. armed forces by order of President Harry S. Truman in July 1948 via Executive Order 9981.

Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. served as commander of the Tuskegee Airmen during the war. He later went on to become the first African-American general in the United States Air Force. His father, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., had been the first African-American brigadier general in the Army (1940).

Doris Miller, a Navy mess attendant, was the first African-American recipient of the Navy Cross, awarded for his actions during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Miller had voluntarily manned an anti-aircraft gun and fired at the Japanese aircraft, despite having no prior training in the weapon's use.

In 1944, the Golden Thirteen became the Navy's first African-American commissioned officers. Samuel L. Gravely, Jr. became a commissioned officer the same year; he would later be the first African American to command a US warship, and the first to be an admiral.

The Port Chicago disaster on July 17, 1944, was an explosion of about 2,000 tons of ammunition as it was being loaded onto ships by black Navy sailors under pressure from their white officers to hurry. The explosion in Northern California killed 320 military and civilian workers, most of them black. It led a month later to the Port Chicago Mutiny, the only case of a full military trial for mutiny in the history of the U.S. Navy against 50 African-American sailors who refused to continue loading ammunition under the same dangerous conditions. The trial was observed by the then young lawyer Thurgood Marshall and ended in conviction of all of the defendants. The trial was immediately and later criticized for not abiding by the applicable laws on mutiny, and it became influential in the discussion of desegregation.

During World War II, most male African-American soldiers still served only as truck drivers and as stevedores (except for some separate tank battalions and Army Air Forces escort fighters).[51] African-American women in uniform answered the call of duty by tending the wounded as nurses, or working as riveters, mail clerks, file clerks, typists, stenographers, supply clerks, or motor pool drivers.[52] In the midst of the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, General Eisenhower was severely short of replacement troops for existing all-white companies. Consequently, he made the decision to allow 2000 black servicemen volunteers to serve in segregated platoons under the command of white lieutenants to replenish these companies.[53] These platoons would serve with distinction and, according to an Army survey in the summer of 1945, 84% were ranked "very well" and 16% were ranked "fairly well". No black platoon received a ranking of "poor" by those white officers or white soldiers that fought with them. These platoons were often subject to racist treatment by white military units in occupied Germany and were quickly sent back to their old segregated units after the end of hostilities in Germany. Despite their protests, these brave African-American soldiers ended the war in their old non-combat service units. Though largely forgotten after the war, the temporary experiment with black combat troops proved a success - a small, but important step toward permanent integration during the Korean War.[54][55] A total of 708 African Americans were killed in combat during World War II.[56]

In 1945, Frederick C. Branch became the first African-American United States Marine Corps officer. In 1965, Marcelite J. Harris became the first female African American United States Air Force officer.

Units

Some of the most notable African-American Army units that served in World War II:

- 92nd Infantry Division

- 93rd Infantry Division

- 2nd Cavalry Division

- Air Corps Units

- Non Divisional Units

- Anti-Aircraft Artillery Unit

- Infantry Units

- Cavalry/Armor Units

- US Military Academy Cavalry Squadron

- 5th Reconnaissance Squadron

- 758th Tank Battalion

- 761st Tank Battalion

- 784th Tank Battalion

- Field Artillery Units

- 46th Field Artillery Brigade.[60]

- 184th Field Artillery Regiment, Illinois National Guard.

- 333rd Field Artillery Regiment.[61]

- 349th Field Artillery Regiment[62]

- 350th Field Artillery Regiment[63]

- 351st Field Artillery Regiment[64]

- 353rd Field Artillery Regiment[65]

- 578th Field Artillery Regiment[66]

- 333rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 349th Field Artillery Battalion

- 350th Field Artillery Battalion

- 351st Field Artillery Battalion

- 353rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 578th Field Artillery Battalion

- 593rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 594th Field Artillery Battalion

- 595th Field Artillery Battalion

- 596th Field Artillery Battalion

- 597th Field Artillery Battalion

- 598th Field Artillery Battalion

- 599th Field Artillery Battalion

- 600th Field Artillery Battalion

- 686th Field Artillery Battalion

- 777th Field Artillery Battalion

- 795th Field Artillery Battalion

- 930th Field Artillery Battalion, Illinois National Guard

- 931st Field Artillery Battalion, Illinois National Guard

- 969th Field Artillery Battalion

- 971st Field Artillery Battalion

- 973rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 993rd Field Artillery Battalion

- 999th Field Artillery Battalion

- Tank Destroyer Units

- 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 646th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 649th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 659th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 669th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 679th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 795th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 827th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 828th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 829th Tank Destroyer Battalion

- 846th Tank Destroyer Battalion

Two segregated units were organized by the United States Marine Corps:

Medal of Honor recipients

On January 13, 1997, President Bill Clinton, in a White House ceremony, awarded the nation's highest military honor—the Medal of Honor—to seven African-American servicemen who had served in World War II.[67]

The only living recipient was First Lieutenant Vernon Baker.

The posthumous recipients were:

- Major Charles L. Thomas

- First Lieutenant John R. Fox

- Staff Sergeant Ruben Rivers

- Staff Sergeant Edward A. Carter, Jr. Carter also has a Military Sealift Command vessel named after him.

- Private First Class Willy F. James, Jr.

- Private George Watson

Blue discharges

African-American troops faced discrimination in the form of the disproportionate issuance of blue discharges. The blue discharge (also called a "blue ticket") was a form of administrative discharge created in 1916 to replace two previous discharge classifications, the administrative discharge without honor and the "unclassified" discharge. It was neither honorable nor dishonorable.[68] Of the 48,603 blue discharges issued by the Army between December 1, 1941, and June 30, 1945, 10,806 were issued to African Americans. This accounts for 22.2% of all blue discharges, when African Americans made up 6.5% of the Army in that time frame.[69] Blue discharge recipients frequently faced difficulties obtaining employment[70] and were routinely denied the benefits of the G. I. Bill by the Veterans Administration (VA).[71] In October 1945, Black-interest newspaper The Pittsburgh Courier launched a crusade against the discharge and its abuses. Calling the discharge "a vicious instrument that should not be perpetrated against the American Soldier", the Courier rebuked the Army for "allowing prejudiced officers to use it as a means of punishing Negro soldiers who do not like specifically unbearable conditions". The Courier specifically noted the discrimination faced by homosexuals, another group disproportionately discharged with blue tickets, calling them "'unfortunates' of the Nation...being preyed upon by the blue discharge" and demanded to know "why the Army chooses to penalize these 'unfortunates' who seem most in need of Army benefits and the opportunity to become better citizens under the educational benefits of the GI Bill of Rights".[72] The Courier printed instructions on how to appeal a blue discharge and warned its readers not to quickly accept a blue ticket out of the service because of the negative effect it would likely have on their lives.[73]

The House Committee on Military Affairs held hearings in response to the press crusade, issuing a report in 1946 that sharply criticized its use and the VA for discriminating against blue discharge holders.[74] Congress discontinued the blue discharge in 1947,[75] but the VA continued its practice of denying G. I. Bill benefits to blue-tickets.[71]

Integration of the armed forces

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981 integrating the military and mandating equality of treatment and opportunity. It also made it illegal, per military law, to make a racist remark. Desegregation of the military was not complete for several years, and all-black Army units persisted well into the Korean War. The last all-black unit wasn't disbanded until 1954.

In 1950, Lieutenant Leon Gilbert of the still-segregated 24th Infantry Regiment was court martialed and sentenced to death for refusing to obey the orders of a white officer while serving in the Korean War. Gilbert maintained that the orders would have meant certain death for himself and the men in his command. The case led to worldwide protests and increased attention to segregation and racism in the U.S. military. Gilbert's sentence was commuted to twenty and later seventeen years of imprisonment; he served five years and was released.

The integration commanded by Truman's 1948 Executive Order extended to schools and neighborhoods as well as military units. Fifteen years after the Executive Order, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara issued Department of Defense Directive 5120.36. "Every military commander", the Directive mandates, "has the responsibility to oppose discriminatory practices affecting his men and their dependents and to foster equal opportunity for them, not only in areas under his immediate control, but also in nearby communities where they may gather in off-duty hours."[76] While the directive was issued in 1963, it was not until 1967 that the first non-military establishment was declared off-limits. In 1970 the requirement that commanding officers first obtain permission from the Secretary of Defense was lifted, and areas were allowed to be declared housing areas off limits to military personnel by their commanding officer.[77]

Since the end of military segregation and the creation of an all-volunteer army, the American military saw the representation of African Americans in its ranks rise precipitously.[78]

Korean War

Jesse L. Brown became the U.S. Navy's first black aviator in October 1948. He died when his plane was shot down during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir in North Korea. He was unable to parachute from his crippled F4U Corsair and crash-landed successfully. His injuries and damage to his aircraft prevented him from leaving the plane. A white squadron mate, Thomas Hudner, crash-landed his F4U Corsair near Brown and attempted to extricate Brown but could not and Brown died of his injuries. Hudner was awarded the Medal of Honor for his efforts. The U.S. Navy honored Jesse Brown by naming a frigate after him—the USS Jesse L. Brown (FF-1089).[79]

Two enlisted men from the 24th Infantry Regiment (still a segregated unit), Cornelius H. Charlton and William Thompson, posthumously received the Medal of Honor for actions during the war.

Vietnam War

.jpg)

The Vietnam War saw many great accomplishments by many African Americans, including twenty who received the Medal of Honor for their actions. African Americans were over-represented in hazardous duty and combat roles during the conflict, and suffered disproportionately higher casualty rates. Civil rights leaders protested this disparity during the early years of the war, prompting reforms that were implemented in 1967–68 resulting in the casualty rate dropping to slightly higher than their percentage of the total population.[80][81][82][83]

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented the Medal of Honor to U.S. Army Specialist Five Lawrence Joel, for a "very special kind of courage—the unarmed heroism of compassion and service to others." Joel was the first living African American to receive the Medal of Honor since the Mexican–American War. He was a medic who in 1965 saved the lives of U.S. troops under ambush in Vietnam and defied direct orders to stay to the ground, walking through Viet Cong gunfire and tending to the troops despite being shot twice himself. The Lawrence Joel Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, is dedicated to his honor.[84]

On August 21, 1968, with the posthumous award of the Medal of Honor, U.S. Marine James Anderson, Jr. became the first African-American U.S. Marine recipient of the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions and sacrifice of life.

On December 10, 1968, U.S. Army Captain Riley Leroy Pitts became the first African-American commissioned officer to be awarded the Medal of Honor. His medal was presented posthumously to his wife, Eula Pitts, by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Three out of the 21 African-American Medal of Honor recipients who served in Vietnam were members of the 5th Special Forces Group otherwise known as The Green Berets. These men are as follows: Sergeant First Class Melvin Morris, SFC. Eugene Ashley, Jr., and SFC. William Maud Bryant.

Melvin Morris received the Medal of Honor 44 years after the action in which he earned the Distinguished Service Cross. Sergeant Ashley's medal was posthumously awarded to his family at the White House by Vice President Spiro T. Agnew on December 2, 1969.

Post-Vietnam to present day

In 1989, President George H. W. Bush appointed Army General Colin Powell to the position of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, making Powell the highest-ranking officer in the United States military. Powell was the first, and is so far the only, African American to hold that position. The Chairman serves as the chief military adviser to the President and the Secretary of Defense. During his tenure Powell oversaw the 1989 United States invasion of Panama to oust General Manuel Noriega and the 1990 to 1991 Gulf War against Iraq. General Powell's four-year term as Chairman ended in 1993.

General William E. "Kip" Ward was officially nominated as the first commander of the new United States Africa Command on July 10, 2007 and assumed command on October 1, 2007.

The previous Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps, Carlton W. Kent, is African American; as were the previous two before him. Current Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps, Ronald L. Green is also African-American.

On January 20, 2009, Barack Obama was inaugurated as President of the United States, making him ex officio the first African-American Commander-in-Chief of the United States Armed Forces.

Military history of African Americans in popular culture

The following is a list of notable African-American military members or units in popular culture.

| Release Date (or Year) | Name (or event) | Notability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1944 | The Negro Soldier | a Frank Capra recruitment documentary | [85] |

| 1945 | Wings for This Man | a "propaganda" short about the Tuskegee Airmen was produced by the First Motion Picture Unit of the Army Air Forces. The film was narrated by Ronald Reagan. | [86] |

| 1972 | DC Comics | John Stewart of the Green Lanterns was created as an African-American Marine | |

| 1984 | A Soldier's Story | a 1984 drama film directed by Norman Jewison, based upon Charles Fuller's Pulitzer Prize-winning Off Broadway production A Soldier's Play. A black officer is sent to investigate the murder of a black sergeant in Louisiana near the end of World War II. | [87] |

| 1989 | Glory | film featuring the 54th Union regiment composed of African-American soldiers. Starring Denzel Washington and Matthew Broderick | |

| 1990 | The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson | A film about the early life of the baseball star in the army, particularly his court-martial for insubordination regarding segregation. | |

| January 31, 1992 | Family Matters ABC TV series | In the episode entitled "Brown Bombshell", Estelle (portrayed by actress Rosetta LeNoire) is determined to share the stories of her late fighter-pilot husband and World War II's Tuskegee Airmen to an uninterested Winslow clan. Eventually, she is invited to share her stories to Eddie's American history class. | [88] |

| 1996 | The Tuskegee Airmen | Produced and aired by HBO and starring Laurence Fishburne. | [89] |

| 1997 | G.I. Joe action figure series | The Tuskegee Airmen are represented. | [90] |

| 1999 | Mutiny | TV made film of the 1944 Port Chicago disaster | |

| 2001 | The Wild Blue: The Men and Boys who Flew the B-24s over Germany | Book, by Stephen Ambrose where the Tuskegee Airmen were mentioned and honored. | [91] |

| 2001–2005 | JAG | The Commander Peter Ulysses Sturgis Turner (played by Scott Lawrence) is an African-American Navy Officer in the JAG TV series. Former submarine officer, he serves now as lawyer in JAG | |

| 2002 | JAG: "Port Chicago" | The television drama features the incident | |

| 2002 | Hart's War | a film about a World War II prisoner of war (POW) based on the novel by John Katzenbach | |

| 2004 | Silver Wings and Civil Rights: The Fight to Fly | this documentary was the first film to feature information regarding the "Freeman Field Mutiny", the struggle of 101 African-American officers arrested for entering a white officers' club. | [92] |

| 2005 | Willy's Cut & Shine | a play by Michael Bradford depicting African-American World War II soldiers and the troubles they encounter upon returning home to the Deep South. | [93] |

| 2008 | Miracle at St. Anna | Italian epic war film set primarily in Italy during German-occupied Europe in World War II. Directed by Spike Lee, the film is based on the eponymous 2003 novel by James McBride, who also wrote the screenplay. | [94] |

| 2009 | Fly | a play about the Tuskegee Airmen | [95] |

| 2010 | For Love of Liberty | a PBS documentary television series that portrays African-American servicemen and women and their dedicated allegiance to the United States military. | [96] |

| 2012 | Red Tails | George Lucas announced he was planning a film about the Tuskegee Airmen. In his release Lucas says, "They were the only escort fighters during the war that never lost a bomber so they were, like, the best." | [97] |

See also

- Afro-Asian

- Military history of the United States

- United States Colored Troops

- List of African American Medal of Honor recipients

- Frederick C. Branch

- Benjamin O. Davis

- Martin Delany

- Daniel "Chappie" James, Jr.

- National Association for Black Veterans

- List of African-American astronauts

- African-American discrimination in the U.S. Military

- Racial segregation in the United States Armed Forces

Notes

- ↑ Gary B. Nash, "The African Americans Revolution", in Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution( 2012) edited by Edward G Gray and Jane Kamensky pp 250–70, at p 254

- ↑ Ray Raphael, A People's History of the American Revolution (2001) p 281

- ↑ "Selig, Robert A. "The Revolution's Black Soldiers" orig. published summer, 1997". AmericanRevolution.org. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Gray, Jefferson M. "Francis Marion Foils the British", Military History Quarterly, pub. online Aug. 3, 2011

- 1 2 3 4 Shaw, Henry I., Jr.; Donnelly, Ralph W. (2002). "Blacks in the Marine Corps" (PDF). Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters USMC. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ↑ Morris, Steven (December 1969). "How Blacks Upset The Marine Corps: 'New Breed' leathernecks are tackling racist vestiges". Ebony. Johnson Publishing Company. 25 (2): 55–58. ISSN 0012-9011.

- ↑ MacGregor, Morris J. (1981). Center of Military History, U.S. Army, ed. Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940–1965. Government Printing Office. pp. 100–102. ISBN 0-16-001925-7.

- ↑ "U.S. Senate: Battle of Lake Erie". Senate.gov. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Copes, p.63. This is in some dispute. See here

- ↑ Battie, Charles A. (1932). "Rhode Island African American Data: HANNIBAL COLLINS". Negroes of Rhode Island. Rhode Island Genealogy Trails. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- 1 2 "African American History & the Civil War(CWSS)". NPS.gov. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Charles Ball Slavery in the United States: A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles Ball, a Black Man, Who Lived Forty Years in Maryland, South Carolina and Georgia, as a Slave Under Various Masters, and was One Year in the Navy with Commodore Barney, During the Late War (New York: John S. Taylor 1837).

- ↑ Charles E. Brodine, Michael J. Crawford and Christine F. Hughes, editors Ironsides! The Ship, the Men and the Wars of the USS Constitution (Fireship Press, 2007), 50

- ↑ Elizabeth Dowling Taylor A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madison’s Palgrave (McMillen: New York 2012), p.49.

- ↑ Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With the Names of American Wounded from the Battle of Bladensburg Transcribed with Introduction and Notes by John G. Sharp Harry Jones was patient number 35 and see note 8. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html Accessed 22 May 2018

- ↑ The text of the proclamation has been widely published, and copies of the printed original are in UK National Archives WO 1/143 f31 and ADM 1/508 f579

- ↑ Morriss, p98

- ↑ William S. Dudley, editor The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History Volume II. (Naval Historical Center: Washington, DC 1992), 324-325

- ↑ Alan Taylor The Internal Enemy Slavery and War In Virginia. 1772 -1832, (WW Norton & Company: New York, 2013), 300-305 and Appendix B.

- ↑ Herbert Aptheker "Negro Casualties in the Civil War" The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 32, No. 1. (January 1947), p. 12.

- ↑ Bruce Levine, Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves during the Civil War (2005).

- ↑ William H. Leckie and Shirley A. Leckie, The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Black Cavalry in the West (University of Oklahoma Press, 2012)

- ↑ Charles L. Kenner, Buffalo Soldiers and Officers of the Ninth Cavalry, 1867–1898: Black and White Together (University of Oklahoma Press, 2014)

- ↑ Frank N. Schubert, Black Valor: Buffalo Soldiers and the Medal of Honor, 1870–1898 (1997)

- ↑ Heitland, Jason. "The Role of the Buffalo Soldiers During the Plains Indian Wars". us7thcavcof.com. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ McCard, Harry Stanton; Turnley, Henry (1899). "History of the Eighth Illinois United States Volunteers". Chicago: E. F. Harman & Co.

- ↑ "A HOMAGE TO DAVID FAGEN, AFRICAN-AMERICAN SOLDIER IN THE PHILIPPINE REVOLUTION". www.academia.edu. p. 20. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Rudy Rimando, "Interview with Historical Novelist William Schroder: Before Iraq, There Was the Philippines", November 28, 2004, hnn.us History news Network". HNN.us. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Ryan, David (2014). Cullinane, Michael Patrick, ed. U.S. Foreign Policy and the Other. Berghahn. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-1782384397. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ↑ William T. Bowers; William M. Hammond; George L. MacGarrigle (May 1997). Black Soldier, White Army: The 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea. DIANE Publishing. pp. 12. ISBN 978-0-7881-3990-1.

- ↑ "The Saga of David Fagen". Archive.org. 27 October 2009. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ African-Americans Continue Tradition of Distinguished Service; U.S. Army; Gerry J. Gilmore; February 2, 2007

- ↑ Patterson, Michael Robert. "Freddie Stowers, Corporal, United States Army". ArlingtonCemetery.net. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ "African American World War II Medal of Honor Recipients". U.S. Army Center of Military History. February 3, 2011. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ↑ Video: U.S. Air ForAllied Bombers Strike On Two Fronts Etc (1945). Universal Newsreel. 1945. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Complete History of the Colored Soldiers in the World War". New York: Bennett & Churchill. 1919.

- ↑ Sweeney, W. Allison (1919). "History of the American Negro in the Great World War".

- ↑ Scott, Emmett J. Scott's Official History of The American Negro in the World War. p. 316. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ↑ African Americans in the Spanish Civil War: "This Ain't Ethiopia, But It'll Do." Edited by Danny Duncan Collum. Victor A. Berch, chief researcher. New York: G.K. Hall and Co., 1992.

- ↑ Aric Putnam "Ethiopia is Now: J. A. Rogers and the Rhetoric of Black Anticolonialism During the Great Depression" Rhetoric & Public Affairs – Volume 10, Number 3, Fall 2007, p. 419

- 1 2 Gerald A. Danzer, J. Jorge Klor De Alva, Larry S. Krieger (2003). The Americans: Reconstruction to the 21st Century. McDougal Littell.

- ↑ Rowley, Hazel (2008). Richard Wright: The Life and Times. University of Chicago Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-226-73038-7.

- ↑ "Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Spanish Civil War History and Education: James Lincoln Holt Peck". ALBA-VALB.org. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Gail Lumet Buckley, American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm, ISBN 978-0-375-50279-8

- ↑ "O'Reilly, Salaria Kee (1913-1991) - The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". BlackPast.org. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ The Pittsburgh Courier December 13, 1941 pg. 1

- ↑ "Interview with Oneida Miller Stuart". memory.loc.gov.

- ↑ 1969-, Ellis, Jacqueline, (1998). Silent witnesses : representations of working-class women in the United States. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 9780879727444. OCLC 36589970.

- ↑ "Phyllis Mae Dailey: First Black Navy Nurse - The National WWII Museum Blog". NWW2M.com. March 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Lee, Ulysses (1966). The Employment of Negro Troops. U.S. Army.

- ↑ Blumenson, Martin (1972), Eisenhower, New York: Ballantine Books, p. 127

- ↑ "The Women's Army Corps". Army.mil. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Young, William H.; Young, Nancy K., eds. (2010), World War II and the Postwar Years in America: A Historical and Cultural Encyclopedia, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, p. 534, ISBN 0-313-35652-1

- ↑ Colley, David (2006), African American Platoons in WWI, www.historynet.com

- ↑ "African American Platoons in World War II | HistoryNet". HistoryNet. October 20, 2006. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ↑ Michael Clodfelter. Warfare and Armed Conflicts- A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500–2000. 2nd Ed. 2002 ISBN 0-7864-1204-6.

- 1 2 "Historic California Posts: Camp Lockett". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ↑ "The 28th Cavalry: The U.S. Army's Last Horse Cavalry Regiment". Archived from the original on 2007-12-20. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ "Defending the Border: The Cavalry at Camp Lockett". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ↑ Unit subsequently reorganized and redesignated the 46th Field Artillery Group.

- ↑ Unit subsequently reorganized and redesignated as the 333rd Field Artillery Group.

- ↑ Unit subsequently reorganized and redesignated as the 349th Field Artillery Group.

- ↑ Unit subsequently reorganized and redesignated as the 350th Field Artillery Regiment

- ↑ Unit subsequently reorganized and redesignated the 351st Field Artillery Group.

- ↑ Subsequently, unit reorganized and redesignated the 353rd Field Artillery Group

- ↑ Unit subsequently reorganized and redesignated the 578th Field Artillery Group

- ↑ "World War II African American Medal of Honor Recipients". United States Army Center of Military History.

- ↑ Jones, p. 2

- ↑ McGuire, p. 146

- ↑ Shilts, p. 164

- 1 2 Bérubé, p. 230

- ↑ Quoted in Bérubé, p. 233

- ↑ Bérubé, p. 241

- ↑ Bérubé, p. 234

- ↑ Associated Press (1947-05-21). "Army to abandon 'blue' discharge". Jefferson City (MO) Daily Capital News. p. 1.

- ↑ Department of Defense Directive 5120.36

- ↑ Heather Antecol and Deborah Cobb-Clark, Racial and Ethnic Harassment in Local Communities. October 4, 2005. p 8

- ↑ John Sibley Butler. "Affirmative Action in the Military Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science", Vol. 523, Affirmative Action Revisited (Sep., 1992), pg. 196.

- ↑ "USS Jesse L. Brown". Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy.

- ↑ War within war; The Guardian; September 15, 2001

- ↑ Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam: American Combat; Christian G. Appy; University of North Carolina Press; Pg. 19

- ↑ Fighting on Two Fronts: African Americans and the Vietnam War; Westheider, James E.; New York University Press; 1997; pgs. 11–16

- ↑ African-Americans In Combat

- ↑ "Who is Lawrence Joel?". Lawrence Joel Veterans Memorial Coliseum – Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Archived from the original on 2010-12-28. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ↑ The Negro Soldier on IMDb

- ↑ Wings for This Man on IMDb

- ↑ A Soldier's Story on IMDb

- ↑ "TV.com Family Matters Episodes: Season 3". Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ↑ The Tuskegee Airmen on IMDb

- ↑ "1997 G.I. Joe Classic Collection". MasterCollector.com. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Ambrose, Stephen Edward The Wild Blue: The Men and Boys who Flew the B-24s over Germany, Simon & Schuster, 2001, Chapter 9, p. 27

- ↑ "Silver Wings and Civil Rights: The Flight to Fly". Fight2Fly.com. Archived from the original on March 20, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Bradford, Michael (2006). Willy's Cut & Shine (first 15 pages) (PDF) (Second ed.). Broadway Play Publishing Inc. ISBN 0-88145-269-6.

- ↑ Miracle at St. Anna

- ↑ Gates, Anita, "Breathing new life into an oft-told tale," The New York Times, October 9, 2009, retrieved September 29, 2012

- ↑ "For Love of Liberty: The Story of America's Black Patriots". ForLoveOfLiberty.org. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ "Exclusive: Lucas looks to the future". FilmFocus.co.uk. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

References

- Bérubé, Allan (1990). Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two. New York, The Penguin Group. ISBN 0-452-26598-3 (Plume edition 1991).

- Copes, Jan M. (Fall 1994). "The Perry Family: A Newport Naval Dynasty of the Early Republic". Newport History: Bulletin of the Newport Historical Society. Newport, RI: Newport Historical Society. 66, Part 2 (227): 49–77.

- Jones, Major Bradley K. (January 1973). "The Gravity of Administrative Discharges: A Legal and Empirical Evaluation" The Military Law Review 59:1–26.

- McGuire, Phillip (ed.) (1993). Taps for a Jim Crow Army: Letters from Black Soldiers in World War II. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0822-5.

- Morriss, Roger (1997). Cockburn and the British Navy in Transition: Admiral Sir George Cockburn, 1772–1853. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-253-X

- Shilts, Randy (1993). Conduct Unbecoming: Gays & Lesbians in the U.S. Military Vietnam to the Persian Gulf. New York, St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-09261-X

Further reading

- Alt, William E.; Alt, Betty L. (2002). Black Soldiers, White Wars: Black Warriors from Antiquity to the Present. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97621-7.

- Buckley, Gail (2001). American Patriots:The Story of Blacks in the Military From the Revolution to Desert Storm. Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-76009-9.

- Dalessandro, Robert J.; Gerald Torrence (2009). Willing Patriots: Men of Color in the First World War. Schiffer. ISBN 978-0-7643-3233-3.

- David, Jay; Crane, Elaine (1971). The Black Soldier. William Morrow and Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-688-06037-4.

- Fletcher, Marvin E. (1974). The Black Soldier and Officer in the United States Army 1891–1917. University of Missouri. ISBN 978-0-8262-0161-4.

- Foner, Jack D. (1974). Blacks and the Military in American History. Praeger.

- Gibson, Truman K., Jr.; Steve Huntley (2005). Knocking Down Barriers: My Fight for Black America. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-2292-8. Archived from the original on 2006-09-01.

- Höhn, Maria; Martin Klimke (2010). A Breath of Freedom: The Civil Rights Struggle, African American GIs, and Germany. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-10473-0.

- Knauer, Christine (2014). Let Us Fight as Free Men: Black Soldiers and Civil Rights. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Lindenmeyer, Otto (1970). Black and Brave: The Black Soldier in America. McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 978-0-07-037876-6.

- Nell, William C. (1855). The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution.

- Scott, Emmett J. Scott's Official History of The American Negro in the World War. Retrieved 2014-02-09.

- Sutherland, Jonathan. (2004). African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-746-7

Navy

- Aptheker, Herbert. "The Negro in the Union Navy." Journal of Negro History (1947): 169–200. in JSTOR

- Bennett, Michael J. Union Jacks: Yankee Sailors in the Civil War: Yankee Sailors in the Civil War (U of North Carolina Press, 2005)

- Bureau of Naval Personnel, "The Negro in the Navy in World War II." Washington, 1947. 103 pp. online

- Davis, Michael Shawn. "'Many of them are among my best men': The United States Navy looks at its African American crewmen, 1755-1955." PhD dissertation, Kansas State U. (2011). online, with detailed bibliography pp 216–241

- Jackson, Luther P. "Virginia Negro Soldiers and Seamen in the American Revolution." Journal of Negro History (1942): 247–287. in JSTOR

- Langley, Harold D. "The Negro in the Navy and Merchant Service—1789-1860 1798." Journal of Negro History (1967): 273–286. [ in JSTOR]

- Miller, Richard E. (2004). The Messman Chronicles: African Americans in the U.S. Navy, 1932–1943. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-539-X.

- Miller, Richard E. "The Golden Fourteen, Plus: Black Navy Women in World War One." Minerva: A Quarterly Report on Women and the Military 8.3&4 (1995): 7–13.

- Nelson, Dennis D. The Integration of the Negro into the U.S. Navy, 1776–1947 (NY: Farrar Strauss, 1951)

- Ramold, Steven J. Slaves, Sailors, Citizens: African Americans in the Union Navy (2002)

- Reddick, Lawrence D. "The Negro in the United States Navy During World War II." Journal of Negro History (1947): 201-219. in JSTOR

- Schneller, Jr. Robert J. Blue & Gold and Black: Racial Integration of the U.S. Naval Academy (Texas A&M University Press, 2008)

- Valuska, David L. The African American in the Union Navy, 1861–1865 (Garland Pub., 1993)

- Williams III, Charles Hughes. "We Have … Kept The Negroes' Goodwill And Sent Them Away": Black Sailors, White Dominion In The New Navy, 1893–1942 PhD Dissertation. Texas A&M University, 2008. online

External links

- McDaniels III, Pellom: African American Soldiers (USA) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Sheffer, Debra J.: Racism in the Armed Forces (USA) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- "African Americans in the U.S. Army". U.S. Army.

- "Blacks in the U.S. Army: Then and Now". U.S. Army.

- "Story of America's Black Patriots". U.S. Army.

- Simpson, Diana (compiled by) (February 1999). "African-Americans in Military History". Air University Library, Maxwell Air Force Base.

- "Black History at Arlington National Cemetery". Historical Information. Arlington National Cemetery. Archived from the original on 2000-08-17. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- Black Confederates documentary book

- "Black Military World".

- "Black Military History: African Americans in the service of their country". Father Ryan High School. Archived from the original on 2007-04-03. Retrieved 2005-12-23.

- "A Chronology of African American Military Service: From the Colonial Era through the Antebellum Period". Archived from the original on 2009-10-02.

- First Kansas Colored Infantry flag, Civil War, Kansas Museum of History

- The "Colored" Soldiers, Kansas Historical Society

- Military history of African Americans is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- "The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II at Pritzker Military Museum and Library".