Memphis sanitation strike

The Memphis sanitation strike began in February 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. Following years of poor pay and dangerous working conditions, and provoked by the crushing to death of workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker in garbage compactors, over 700 of the 1300 black sanitation workers met on Sunday, February 11, and agreed to strike.[1] They then did not turn out for work on the following day.[2] They also sought to join the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Local 1733.[3][4] The sanitation strike was also the reason for Martin Luther King Jr.'s presence in Memphis, where he was assassinated.

Memphis's mayor, Henry Loeb, declared the strike illegal and refused to meet with local black leaders (he did meet with AFSCME's national officers).[4] Heavily redacted files released in 2012 suggest that the FBI monitored the strike and increased its operations in Memphis during 1968.[5]

Background

The city of Memphis had a long history of segregation and unfair treatment for black residents. The influential politician E. H. Crump had created a city police force, much of it culled from the Ku Klux Klan, that acted violently toward the black population and maintained Jim Crow. Blacks were excluded from unions and paid much less than whites—conditions which persisted and sometimes worsened in the first half of the 20th century.[6]

During the New Deal, blacks were able to organize as part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, a group which Crump called communist "nigger unionism."[7] However, organized black labor was set back by anti-communist fear after World War II. Civil rights and unionism in Memphis were thus heavily stifled all through the 1950s.[6]

The civil rights struggle was renewed in the 1960s, starting with desegregation sit-ins in the summer of 1960. The NAACP and SCLC were particularly active in Memphis during this period.[8]

Memphis sanitation workers were mostly black. They enjoyed few of the protections that other workers had; their pay was low and they could be fired (usually by white supervisors) without warning. In 1968, these workers were earning between $1.60 and $1.90 an hour. In addition to their sanitation work, often including unpaid overtime, many worked other jobs or appealed to welfare and public housing.[9]

Union activities

Black sanitation workers had been attempting to organize since 1960, when T. O. Jones and O. Z. Evers began signing workers up with the Teamsters. However, many blacks were afraid to unionize due to fear of persecution. This fear proved justified in 1963, when 33 workers (including Jones) were all fired immediately after an organizing meeting they attended. Nevertheless, AFSCME Local 1733 was successfully formed in November 1964.[9]

A strike in August 1966 was thwarted before it began when the city prepared strikebreakers and threatened to jail leaders.[9]

Precursors

At the end of 1967, Henry Loeb was elected as mayor against the opposition of Memphis's black community. Loeb had served previously as the head of the sanitation division (as the elected Public Works Commissioner), and during his tenure oversaw grueling work conditions — including no city-issued uniforms, no restrooms, and no grievance procedure for the numerous occasions on which they were underpaid.[10]

Upon taking office, Loeb increased regulations on the city's workers and appointed Charles Blackburn as the Public Works Commissioner. Loeb ordered Jones and the union to deal with Blackburn; Blackburn said he had no authority to change the city's policies.[11]

On February 1, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, two sanitation workers[12], were crushed to death in a garbage compactor where they were taking shelter from the rain. Two other men had died this way in 1964, but the city refused to replace the defective equipment. On February 12, hundreds of workers came to a meeting at the Memphis Labor Temple, furious with their working conditions. The workers left the meeting with no organized plan, but a feeling that something had to be done—immediately.[11]

Course of the strike

On Monday, February 12, 1,375 men (mostly sanitation and sewage workers but also other employees of Memphis' Department of Public Works) did not show up for work.[13] Some of those who did show up walked off when they found out about the apparent strike. Mayor Loeb, infuriated, refused to meet with the strikers.[11]

The workers marched from their union hall to a meeting at the City Council chamber; there, they were met with 40–50 police officers. Loeb led the workers to a nearby auditorium, where he asked them to return to work. They laughed and booed him, then applauded union leaders who spoke. At one point, Loeb grabbed the microphone from AFSCME International organizer Bill Lucy and shouted "Go back to work!", storming out of the meeting soon after.[11] The workers declined.

By February 15, piles of trash (10,000 tons worth) were noticeable, and Loeb began to hire strikebreakers. These individuals were white and traveled with police escorts. They were not well received by the strikers, and the strikers assaulted the strikebreakers in some cases.[14][15]

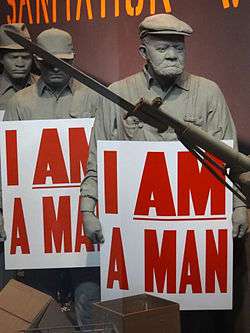

As of February 21, 1968, the sanitation workers established a daily routine of meeting at noon with nearly a thousand strikers and then marching from Clayborn Temple to downtown.[16] The marchers faced police brutality in the forms of mace, tear gas, and billy clubs. On February 24, while addressing the strikers after a "police assault" on their protests, Reverend James Lawson said, "For at the heart of racism is the idea that a man is not a man, that a person is not a person. You are human beings. You are men. You deserve dignity." Rev. Lawson's comments embody the message behind the iconic placards from the sanitation workers' strike, "I Am A Man".

On the evening of February 26, Clayborn Temple held over a thousand supporters of the movement. Reverend Ralph Jackson charged the crowd to not rest until "justice and jobs" prevailed for all black Americans. That night they raised $1,600 to support the Movement. Rev. Jackson declared further that once the immediate demands of the strikers were met, the movement would focus on ending police brutality, as well as improving housing and education across the city for black Memphians.[16]

Our Henry, who art in City Hall,

Hard-headed be thy name.

Thy kingdom C.O.M.E.

Our will be done,

In Memphis, as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our Dues Checkoff,

And forgive us our boycott,

As we forgive those who spray MACE against us.

And lead us not into shame,

But deliver us from LOEB!

For OURS is justice, jobs, and dignity,

Forever and ever. Amen. FREEDOM!— "Sanitation Workers' Prayer" recited by Reverend Malcolm Blackburn[16]

Media coverage

The local news media were generally favorable to Loeb, portraying union leaders (and later Martin Luther King Jr.) as meddling outsiders. The Commercial Appeal wrote editorials (and published cartoons) praising the mayor for his toughness.[17] Newspapers and television stations generally portrayed the mayor as calm and reasonable, and the protesters and organizers as unruly and disorganized.[14]

The Tri-State Defender, an African American newspaper, and The Sou'wester, a local college newspaper, reported the events of the strike from the sanitation workers' perspective. These publications emphasized the brutality of the police reactions to the protestors.[18]

Connection to civil rights movement

From the beginning, strikers refused to erase the racial dimension of the issues at hand. Various speakers from the NAACP addressed the strikers in the union hall.[11] Many of these leaders, including Reverend Samuel Kyles, opposed the alliance with white union leaders who seemed to be riding the strikers' coattails.[14]

Support for the strike in Memphis was divided heavily along racial lines. White strikebreakers increased the workers' resentment. The wider black community became directly involved on Saturday, February 17, with a widely attended meeting at Charles Mason Temple. Bishop J. O. Patterson pledged to help the strikers with food; others present followed his example. On Sunday, February 18, supporters of the strike visited black churches around the city, successfully garnering more support.[14]

On a February 23 demonstration, police changed their demands midway through the event, leading to conflict with the protesters. On February 24, black leaders came together to form Community on the Move for Equality (COME). Due to the efforts of COME, the strike grew into an important event during the Civil Rights Movement, attracting the attention of the NAACP, the national news media, and Martin Luther King Jr. Local clergy members and community leaders also undertook an active campaign, including boycotts and civil disobedience. Civil Rights leaders Roy Wilkins, James Lawson, and Bayard Rustin all participated over the course of the strike.[4]

The strike thus came to represent the broader struggle for equality within Memphis, whose many black residents lived disproportionately in poverty.[19] I Am A Man! emerged as a unifying civil rights theme.[20]

Involvement of Martin Luther King Jr.

Before he died on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. also took an active role in mass meetings and street actions. He first visited the Memphis strike on March 18, speaking to an audience of thousands at Mason Temple.[15]

A demonstration on March 28 (with King in attendance) turned violent when some protesters started breaking windows. Some held signs reading "LOEB EAT SHIT". Police responded with batons and tear gas, killing Larry Payne,[21] a sixteen-year-old boy, with a shotgun.[15] Payne's funeral was held in Clayborn Temple. Despite police pressure to have a private closed-casket funeral in their home, the family held the funeral at Clayborn and had an open casket. Following the funeral the sanitation workers marched peacefully downtown.[16]

Roles of the union

Membership in Local 1733 increased substantially during the course of the strike, more than doubling in the first few days.[11] Its relationship with other unions was complex.

National leadership

The AFSCME leadership in Washington was initially upset to learn of the strike, which they thought would not succeed. P. J. Ciampa, a field organizer for the AFL–CIO, reportedly reacted to news of the strike saying, "Good God Almighty, I need a strike in Memphis like I need another hole in the head!" However, both AFSCME and the AFL–CIO sent representatives to Memphis; these organizers came to support the strike upon recognizing the determination of the workers.[11]

Jones, Lucy, Ciampa, and other union leaders, asked the striking workers to focus on labor solidarity and downplay racism. The workers refused.[11]

Local unions

During the strike, Local 1733 received direct support from URW Local 186. Local 186 had the largest black membership in Memphis, and allowed the strikers to use their union hall for meetings.[11] Most white union leaders in Memphis feared the blackness of the strikers, and expressed concern about race riots. Tommy Powell, president of the Memphis Labor Council, was one of few local white advocates.[14]

End of the strike

King's assassination (April 4, 1968) intensified the strike. Mayor Loeb and others feared rioting, which had already begun in Washington, D.C., Federal officials, including Attorney General Ramsey Clark, urged Loeb to make concessions to the strikers in order to avoid violence. Loeb refused.[22] On April 8, a completely silent march with the SCLC and Coretta Scott King attracted 42,000 participants.[4][19] The strike ended on April 16, 1968, with a settlement that included union recognition and wage increases, although additional strikes had to be threatened to force the City of Memphis to honor its agreements. The period was a turning point for black activism and union activity in Memphis.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ "Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike (1968)", King Encyclopedia, Stanford University, archived from the original on January 19, 2017

- ↑ Melvyn Dubofsky, ed. (2013), "Memphis Sanitation Strike (1968)", The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Business, Labor, and Economic History, Oxford University Press, p. 508, ISBN 9780199738816

- ↑ "1968 Memphis Sanitation Strikers Inducted Into Labor Hall Of Fame". Dclabor.org. May 2, 2011. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Navarro, Kylin; Max Rennebohm (September 12, 2010). "Memphis, Tennessee, sanitation workers strike, 1968". Global Nonviolent Action Database. Swarthmore College. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ↑ Perrusquia, Marc (July 3, 2012). "FBI admits noted Memphis civil rights photographer Ernest Withers was informant". The Commercial Appel. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- 1 2 Honey, Michael K. (2007). "A Plantation in the City". Going down Jericho Road the Memphis strike, Martin Luther King's last campaign (1. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04339-6.

The mix of segregation, low wages, anti-union sentiment, and machine politics in Memphis created a particularly deadly legacy for public sector employees.

- ↑ Biles, Roger (September 1, 1984). "Ed crump versus the unions: The labor movement in Memphis during the 1930s". Labor History. 25 (4): 533–552. doi:10.1080/00236568408584775. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ Honey, Michael K. (2007). "Dr. King, Labor, and the Civil Rights Movement". Going down Jericho Road the Memphis strike, Martin Luther King's last campaign. New York [u.a.]: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04339-6.

On February 1, the first lunch-counter 'sit-ins' began in Greensboro, North Carolina; weeks later, in Memphis, a handful of black students followed their example, sitting in and getting arrested for breaking the segregation laws at the city's segregated public libraries.

- 1 2 3 Honey, Michael K. (2007). "Struggles of the Working Poor". Going down Jericho Road the Memphis strike, Martin Luther King's last campaign (1 ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04339-6.

- ↑ "The Accident on a Garbage Truck That Led to the Death of Martin Luther King, Jr". Southern Hollows podcast. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Honey, Michael K. (2007). "On Strike for Respect". Going down Jericho Road the Memphis strike, Martin Luther King's last campaign (1 ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04339-6.

- ↑ "1968 AFSCME Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike Chronology". AFSCME Local 1733 pamphlet. 1968. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 28 Feb 2018.

- ↑ Stanfield, J. Edwin (1968). In Memphis: more than a garbage strike. Atlanta, GA: Southern Regional Council. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Honey, Michael K. (2007). "Hambone's Meditations: The Failure of Community". Going down Jericho Road: The Memphis strike, Martin Luther King's last campaign (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04339-6.

- 1 2 3 Risen, Clay (2009). "King, Johnson, and The Terrible, Glorious Thirty-First Day of March". A nation on fire: America in the wake of the King assassination. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-17710-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Honey, Michael K. (2007). Going Down Jericho Road. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04339-6.

- ↑ Atkins, Joseph B. (2008). "Labor, civil rights, and Memphis". Covering for the bosses : labor and the Southern press. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781934110805. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016.

Like Memphis itself, the editors at the Commercial Appeal and Press-Scimitar felt they had kept their heads largely above the fray during the civil rights battles across the South in the early to mid-1960s, particularly in comparison to the blatantly racist and rabble-rousing histrionics in the two majors newspapers of Mississippi, the Clarion-Ledger and the Jackson Daily News. [...] Yet the sanitation strike of 1968 and Martin Luther King's involvement proved to many black Memphians that the newspapers weren't that different from their sister papers in Mississippi and elsewhere in the South. Blacks picketed both newspapers within a week after the end of the sanitation strike to protest the coverage.

- ↑ "Law Officers Lit Cauldron" (PDF). The Sou'wester. April 3, 1968. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 22, 2016 – via DLynx.

- 1 2 3 Honey, Michael (December 25, 2009). "Memphis Sanitation Strike". Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ↑ Memphis sanitation workers strike in 1968 with "I Am A Man" posters, which emerged as a unifying civil rights theme. Archived December 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Timeline of Events Surrounding the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike". American Social History Project. November 1, 2015. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015.

- ↑ Risen, Clay (2009). "April 5: 'Any Man's Death Diminishes Me'". A nation on fire : America in the wake of the King assassination. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-17710-5.

Bibliography

- Honey, Michael K. (2007). Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King's Last Campaign. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393043396.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Memphis sanitation strike. |

- Strike-related photos, audio, and documents from the AFSCME Archives. Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs. Wayne State University.

- Web Exhibit on the strike from the AFSCME Archives. Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs. Wayne State University. *King's Unfinished Struggle, at Socialist Worker website

- Memphis Sanitation Worker's Strike, at Stanford's KingPapers website

- Labor Rights are Human Rights, from Michael Honey, a professor of History

- The Last Wish of MLK, from NY Times

- The American Prospect explains why MLK was in Memphis

- AFSCME remembers the historical strike

- AFSCME provides a time-line of the relevant events

- The Accident on a Garbage Truck That Led to the Death of Martin Luther King, Jr., episode of the Southern Hollows podcast

- Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike, Civil Rights Digital Library.