Dick Gregory

| Dick Gregory | |

|---|---|

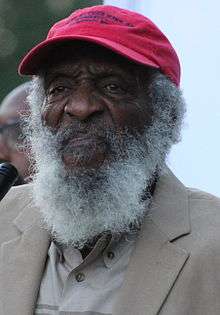

Gregory in 2015 | |

| Birth name | Richard Claxton Gregory |

| Born |

October 12, 1932 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died |

August 19, 2017 (aged 84) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Medium | Civil rights activist, stand-up comedy, film, books, critic |

| Nationality | American |

| Years active | 1954–2017 |

| Subject(s) | American civil rights, politics, culture, African-American culture, racism, race relations, vegetarianism, healthy diet |

| Spouse |

Lillian Smith (m. 1959) |

| Children | 10 |

| Notable works and roles |

In Living Black and White |

| Website | www.dickgregory.com |

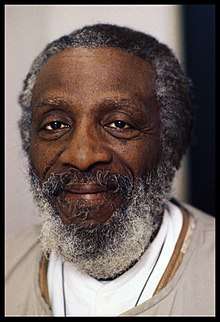

Richard Claxton Gregory (October 12, 1932 – August 19, 2017) was an African-American comedian, civil rights activist, social critic, writer, conspiracy theorist,[1][2] entrepreneur,[3][4] and occasional actor. During the turbulent 1960s, Gregory became a pioneer in stand-up comedy for his "no-holds-barred" sets, in which he mocked bigotry and racism. He performed primarily to black audiences at segregated clubs until 1961, when he became the first black comedian to successfully cross over to white audiences, appearing on television and putting out comedy record albums.[5]

Gregory was at the forefront of political activism in the 1960s, when he protested the Vietnam War and racial injustice. He was arrested multiple times and went on many hunger strikes.[6] He later became a speaker and author, primarily promoting spirituality.[5]

Gregory died of heart failure at a Washington, D.C., hospital at age 84 in August 2017.[5]

Early life

Gregory was born in St. Louis, Missouri, the son of Lucille, a housemaid, and Presley Gregory.[7][8] When he was nine years old, he was the victim of a racist attack for touching a white woman's leg while shining her shoes.[8] At Sumner High School, he was aided by teachers, among them Warren St. James; he also excelled at running. Gregory earned a track scholarship to Southern Illinois University (SIU),[9] where he set school records as a half-miler and miler.[10] He was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. In 1954, his college career was interrupted for two years when he was drafted into the United States Army. At the urging of his commanding officer, who had taken notice of his penchant for joking, Gregory got his start in comedy in the Army, where he entered and won several talent shows. In 1956, Gregory briefly returned to SIU after his discharge, but dropped out because he felt that the university "didn't want me to study, they wanted me to run."[11]

In the hopes of becoming a professional comedian, Gregory moved to Chicago, Illinois, where he became part of a new generation of black comedians that included Nipsey Russell, Bill Cosby, and Godfrey Cambridge, all of whom broke with the minstrel tradition that presented stereotypical black characters. Gregory drew on current events, especially racial issues, for much of his material: "Segregation is not all bad. Have you ever heard of a collision where the people in the back of the bus got hurt?"[12]

Career

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Gregory began his career as a comedian while serving in the military in the mid-1950s. He served in the Army for a year and a half at Fort Hood in Texas, Fort Lee in Virginia, and Fort Smith in Arkansas. He was drafted in 1954 while attending Southern Illinois University. After being discharged in 1956, he returned to the university but did not receive a degree. He moved to Chicago with a desire to perform comedy professionally.[12]

In 1958, Gregory opened the Apex Club nightclub in Illinois. The club failed and landed Gregory in financial hardship. In 1959, Gregory landed a job as master of ceremonies at the Roberts Show Club.[13]

While working for the United States Postal Service during the daytime, Gregory performed as a comedian in small, primarily black-patronized nightclubs. He was one of the first black comedians to gain widespread acclaim while performing for white audiences. In an interview with The Huffington Post, Gregory described the history of black comics as limited: "Blacks could sing and dance in the white night clubs but weren't allowed to stand flat-footed and talk to white folks, which is what a comic does."[14]

In 1961, Gregory was working at the black-owned Roberts Show Bar in Chicago when he was spotted by Hugh Hefner. Gregory was performing the following material before a largely white audience:

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. I understand there are a good many Southerners in the room tonight. I know the South very well. I spent twenty years there one night.

Last time I was down South I walked into this restaurant and this white waitress came up to me and said, "We don't serve colored people here." I said, "That's all right. I don't eat colored people. Bring me a whole fried chicken."

Then these three white boys came up to me and said, "Boy, we're giving you fair warning. Anything you do to that chicken, we're gonna do to you." So I put down my knife and fork, I picked up that chicken and I kissed it. Then I said, "Line up, boys!"[15]

Gregory attributed the launch of his career to Hefner. Based on his performance at Roberts Show Bar, Hefner hired Gregory to work at the Chicago Playboy Club as a replacement for comedian "Professor" Irwin Corey.[16]

Gregory made his first television appearance on the late night show Tonight Starring Jack Paar.[17] He soon began appearing nationally and on television.

Early in his career, Gregory was offered an engagement on Tonight Starring Jack Paar.[17] Paar's show was known for helping propel entertainers to the next level of their careers. At the time, black comics did perform on the show, but after their performances, they were never asked to stay and sit on the famous couch and talk with the host.[18] Dick Gregory declined several invitations from Jack Paar to perform on the show. Paar finally called him to find out why he refused to perform on his show. In order to have Gregory perform, the producers eventually agreed to allow him to stay after his performance and talk with the host on air.[18] This was a first in the show's history. Gregory's interview on Tonight Starring Jack Paar spurred conversations across America.[17]

Gregory's comedy occasioned controversy in some conservative white circles. The administration of the University of Tennessee, for instance, branded Gregory an "extreme racist"[19] whose "appearance would be an outrage and an insult to many citizens of this state",[20] and revoked his invitation by students to speak on campus. The students sued, with noted litigator William Kunstler as their counsel, and in Smith v. University of Tennessee, 300 F. Supp. 777 (E.D. Tenn. 1969), won an order from the court that the University's policy was "too broad and vague". The University of Tennessee then implemented an "open speaker" system, and Gregory subsequently performed in April 1970.[19]

Post-standup career

Gregory was number 82 on Comedy Central's list of the 100 Greatest Stand-ups of all time and had his own star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[21]

He was a co-host with radio personality Cathy Hughes, and was a frequent morning guest, on WOL 1450 AM talk radio's "The Power", the flagship station of Hughes' Radio One.[22] He also appeared regularly on the nationally syndicated Imus in the Morning program.[23]

Gregory appeared as "Mr. Sun" on the television show Wonder Showzen (the third episode, entitled "Ocean", aired in 2005). As Chauncey, a puppet character, imbibes a hallucinogenic substance, Mr. Sun warns, "Don't get hooked on imagination, Chauncey. It can lead to terrible, horrible things." Gregory also provided guest commentary on the Wonder Showzen Season One DVD.[24] Large segments of his commentary were intentionally bleeped out, including the names of several dairy companies, as he made potentially defamatory remarks concerning ill effects that the consumption of cow milk has on human beings.

Gregory attended and spoke at the funeral of James Brown on December 30, 2006, in Augusta, Georgia.[25]

Gregory was an occasional guest on the Mark Thompson's Make It Plain Sirius Channel 146 Radio Show from 3pm to 6pm PST.[26]

Gregory appeared on The Alex Jones Show on September 14, 2010, March 19, 2012, and April 1, 2014.[27][28][29]

Gregory gave the keynote address for Black History Month at Bryn Mawr College on February 28, 2013.[30] His take-away message to the students was to never accept injustice.

Once I accept injustice, I become injustice. For example, paper mills give off a terrible stench. But the people who work there don't smell it. Remember, Dr. King was assassinated when he went to work for garbage collectors. To help them as workers to enforce their rights. They couldn't smell the stench of the garbage all around them anymore. They were used to it. They would eat their lunch out of a brown bag sitting on the garbage truck. One day, a worker was sitting inside the back of the truck on top of the garbage, and got crushed to death because no one knew he was there.[30]

Even as late as 2013, Gregory continued to be a ringing voice of the black power movement. Towards the end of his life, he was featured in a Fantagraphics book by Pat Thomas entitled Listen, Whitey: The Sights and Sounds of Black Power 1965–1975, which uses the political recordings of the Civil Rights era to highlight sociopolitical meanings throughout the movement.[31] Gregory is known for comedic performances that not only made people laugh, but mocked the establishment. According to Thomas, Gregory's monologues reflect a time when entertainment needed to be political to be relevant, which is why he included his standup in the collection. Gregory is featured along with the likes of Huey P. Newton, Jesse Jackson, Martin Luther King Jr., Langston Hughes and Bill Cosby.[32]

Joe Morton played Dick Gregory in 2016 in the play Turn Me Loose at the Westside Theatre in Manhattan.[33]

Personal life

Gregory met his future wife Lillian Gregory[34] at an African-American club; they married in 1959. They had 11 children (including one son, Richard Jr., who died two months after birth): Michele, Lynne, Pamela, Paula, Stephanie (also known as Xenobia), Gregory, Christian, Miss, Ayanna, and Yohance.[12] He was criticized for being an absent father. In a 2000 interview with The Boston Globe, Gregory was quoted as saying, "People ask me about being a father and not being there. I say, 'Jack the Ripper had a father. Hitler had a father. Don't talk to me about family.'"[22]

Activism

Political activism

Gregory was active in the civil rights movement. On October 7, 1963, he came to Selma, Alabama, and spoke for two hours on a public platform two days before the voter registration drive known as "Freedom Day" (October 7, 1963).[35]

In 1964, Gregory became more involved in civil rights activities, activism against the Vietnam War, economic reform, and anti-drug issues. As a part of his activism, he went on several hunger strikes and campaigns in America and overseas. In the early 1970s, he was banned from Australia, where government officials feared he would "...stir up demonstrations against the Vietnam war."[36]

In 1964, Gregory played a role in the search for three missing civil rights workers, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, who vanished in Philadelphia, Mississippi. After Gregory and members of CORE met with Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence A. Rainey, Gregory became convinced that the Sheriff's office was complicit. With cash provided by Hugh Hefner, Gregory announced a $25,000 reward for information. The FBI, which had been criticized for inaction, eventually followed suit with its own reward, and the rewards worked. The bodies of the three men were found by the FBI 44 days after they disappeared.[37]

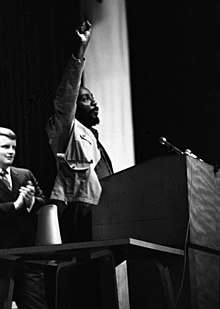

Gregory began his political career by running against Richard J. Daley for Mayor of Chicago in 1967. Though he did not win, this would not prove to be the end of his participation in electoral politics.[38]

Gregory ran for President of the United States in 1968 as a write-in candidate of the Freedom and Peace Party, which had broken off from the Peace and Freedom Party. He garnered 47,097 votes, including one from Hunter S. Thompson,[39] with fellow activist Mark Lane as his running mate in some states. His running mate in New Jersey was Dr. David Frost of Plainfield, a biologist, Rutgers professor, and Chairman of NJ SANE (Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy).Famed pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock was the running mate in Virginia[40] and Pennsylvania[41] garnering more than the party he had left.[42] The Freedom and Peace Party also ran other candidates, including Beulah Sanders for New York State Senate and Flora Brown for New York State Assembly.[43] His efforts landed him on the master list of Nixon's political opponents.

Gregory then wrote the book Write Me In about his presidential campaign. One anecdote in the book relates the story of a publicity stunt that came out of Operation Breadbasket in Chicago. The campaign had printed dollar bills with Gregory's image on them, some of which made it into circulation, causing considerable problems, but priceless publicity. The majority of these bills were quickly seized by the federal government.[10] A large contributing factor to the seizure came from the bills resembling authentic United States currency enough that they worked in many dollar-cashing machines of the time. Gregory avoided being charged with a federal crime, later joking that the bills could not really be considered United States currency, because "everyone knows a black man will never be on a U.S. bill."[44]

Shortly after this time, Gregory became an outspoken critic of the findings of the Warren Commission concerning the assassination of John F. Kennedy by Lee Harvey Oswald. On March 6, 1975, Gregory and assassination researcher Robert J. Groden appeared on Geraldo Rivera's late night ABC talk show Goodnight America. An important historical event happened that night when the famous Zapruder film of JFK's assassination was shown to the public on TV for the first time.[45] The public's response and outrage to its showing led to the forming of the Hart-Schweiker investigation, which contributed to the Church Committee Investigation on Intelligence Activities by the United States, which resulted in the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations investigation.

Gregory was an outspoken feminist, and in 1978 joined Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, Bella Abzug, Margaret Heckler, Barbara Mikulski, and other suffragists to lead the National ERA March for Ratification and Extension, a march down Pennsylvania Avenue to the United States Capitol of over 100,000 on Women's Equality Day (August 26), 1978, to demonstrate for a ratification deadline extension for the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution, and for the ratification of the ERA.[46] The march was ultimately successful in extending the deadline to June 30, 1982, and Gregory joined other activists to the Senate for celebration and victory speeches by pro-ERA Senators, Members of Congress, and activists. The ERA narrowly failed to be ratified by the extended ratification date.

On July 21, 1979, Gregory appeared at the Amandla Festival where Bob Marley, Patti LaBelle, and Eddie Palmieri, amongst others, performed.[47] Gregory gave a speech before Marley's performance, blaming President Carter, and showing his support for the international Anti-Apartheid Movement. Gregory and Mark Lane conducted landmark research into the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., helping move the U.S. House Select Assassinations Committee to investigate the murder, along with that of John F. Kennedy. Lane was the author of conspiracy theory books such as Rush to Judgment. The pair wrote the King conspiracy book Code Name Zorro, which postulated that convicted assassin James Earl Ray did not act alone. Gregory also argued that the moon landing was faked and the commonly accepted account of the 9/11 attacks is incorrect, among other conspiracy theories.[3][4]

Gregory was an outspoken activist during the US Embassy Hostage Crisis in Iran. In 1980, he traveled to Tehran to attempt to negotiate the hostages' release and engaged in a public hunger strike there, weighing less than 100 pounds (45 kg) when he returned to the United States.[48]

In 1998, Gregory spoke at the celebration of the birthday of Dr Martin Luther King Jr., with President Bill Clinton in attendance. Not long after, the President told Gregory's long-time friend and public relations consultant Steve Jaffe, "I love Dick Gregory; he is one of the funniest people on the planet." They spoke of how Gregory had made a comment on Dr. King's birthday that broke everyone into laughter, when he noted that the President made Speaker Newt Gingrich ride "in the back of the plane," on an Air Force One trip overseas.[49]

Gregory was diagnosed with lymphoma in late 1999. He said he was treating the cancer with herbs, vitamins, and exercise, which he believed kept the cancer in remission.[50]

Beginning in the mid-1980s, Gregory was a figure in the health food industry by advocating for a raw fruit and vegetable diet. He wrote the introduction to Viktoras Kulvinskas' book Survival into the 21st Century. Gregory first became a vegetarian in the 1960s and lost a considerable amount of weight by going on extreme fasts, some lasting upwards of 50 days. He developed a diet drink called "Bahamian Diet Nutritional Drink" and went on TV shows advocating his diet and to help the morbidly obese.[38]

In 2003, Gregory and Cornel West wrote letters on behalf of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) to Kentucky Fried Chicken's CEO, asking that the company improve its animal-handling procedures.[51]

At a civil rights rally marking the 40th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Gregory criticized the United States, calling it "the most dishonest, ungodly, unspiritual nation that ever existed in the history of the planet. As we talk now, America is 5 percent of the world's population and consumes 96 percent of the world's hard drugs".[52]

In 2008, Gregory stated he believed that air pollution and intentional water contamination with heavy metals such as lead and possibly manganese may be being used against black Americans, especially in urban neighborhoods, and that such factors could be contributing to high levels of violence in black communities.[53]

On September 10, 2010, Gregory announced that he was going on a hunger strike. In a commentary that was published by the Centre for Research on Globalisation Web site in Montreal, he said that he doubted the official U.S. report about the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

One thing I know is that the official government story of those events, as well as what took place that day at the Pentagon, is just that, a story. This story is not the truth, but far from it. I was born on October 12, 1932. I am announcing today that I will be consuming only liquids beginning Sunday until my eightieth birthday in 2012 and until the real truth of what truly happened on that day emerges and is publicly known.[54]

Health Enterprises, Inc.

In 1984, he founded Health Enterprises, Inc., a company that distributed weight-loss products. With this company, Gregory made efforts to improve the life expectancy of African Americans, which he believed was being hindered by poor nutrition and drug and alcohol abuse.[55] In 1985, Gregory introduced the "Slim-Safe Bahamian Diet", a powdered-diet mix.[56] He launched the weight-loss powder at the Whole Life Expo in Boston under the slogan "It's cool to be healthy". The diet mix, if drunk three times a day, was said to provide rapid weight loss. Gregory received a multimillion-dollar distribution contract to retail the diet.[57]

In 1985, the Ethiopian government adopted, to reported success, Gregory's formula to combat malnutrition during a period of famine in the country.[58] Gregory's clients included Muhammad Ali.[8]

In 2014, Dick Gregory updated his original 4X formula, which was the basis for the Bahamian Diet and created his new and improved "Caribbean Diet for Optimal Health".[59]

Some of his health treatments have been described as "unorthodox" and "profitable rot".[8]

Death

A week prior to his death, Gregory was hospitalized in Washington, D.C., with a bacterial infection.[60] He died at the hospital in Washington, D.C., on August 19, 2017, at the age of 84.[48] The cause was heart failure.[61]

Discography

- In Living Black and White (1961)[62]

- East & West (1961)[62]

- Dick Gregory Talks Turkey (1962)[62]

- The Two Sides of Dick Gregory (1963)[62]

- My Brother's Keeper (1963)

- Dick Gregory Running for President (1964)[62]

- So You See... We All Have Problems (1964)

- Dick Gregory On: (1969)[62]

- The Light Side: The Dark Side (1969)[62]

- Dick Gregory's Frankenstein (1970)[62]

- Live at the Village Gate (1970)[62]

- At Kent State (1971)[62]

- Caught in the Act (1974)[62]

- The Best of Dick Gregory (1997)[63]

- 21st Century "State of the Union" (2001)

- You Don't Know Dick (2016)

Books

- Nigger: An Autobiography by Dick Gregory, an autobiography written with Robert Lipsyte, E. P. Dutton, September 1964. (reprinted, Pocket Books, 1965–present)

- Write me in!, Bantam, 1968.

- From the Back of the Bus

- What's Happening?

- The Shadow that Scares Me

- Dick Gregory's Bible Tales, with Commentary, a book of Bible-based humor. ISBN 0-8128-6194-9

- Dick Gregory's Natural Diet for Folks Who Eat: Cookin' With Mother Nature! ISBN 0-06-080315-0

- (with Shelia P. Moses), Callus on My Soul: A Memoir. ISBN 0-7582-0202-4

- Up from Nigger

- No More Lies; The Myth and the Reality of American History

- Dick Gregory's political primer

- (with Mark Lane), Murder in Memphis: The FBI and the Assassination of Martin Luther King

- (with Mel Watkins), African American Humor: The Best Black Comedy from Slavery to Today (Library of Black America)

- Robert Lee Green, Dick Gregory, daring Black leader

- African American Humor: The Best Black Comedy from Slavery to Today (editor). ISBN 1-55652-430-7

- "Not Poor, Just Broke", short story

- "Defining Moments in Black History: Reading Between the Lies", 2017.

Filmography

- The Leisure Seeker (2017)

- The History of Comedy (2017)

- Ir/Reconcilable (2014)

- Steppin: The Movie (2009)

- One Bright Shining Moment (2006)

- Wonder Showzen (TV Series) (2005)

- Reno 911! (TV Series) (2004)

- The Hot Chick (2002) as Bathroom Attendant

- Children of the Struggle (1999) as Vernon Lee

- Panther (1995) as Rev. Slocum

- The Glass Shield (1994)

- ABC Stage 67 (TV Series) (1967) as Civil Rights Marcher

- Sweet Love, Bitter (1967) as Richie 'Eagle' Stokes

See also

References

- ↑ Wiley, Ed (November 9, 2006). "The 9/11 conspiracy: Rubbish or reality? – US news – Life – Race & ethnicity". MSNBC. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ↑ "Dick Gregory's Role as Michael Jackson's Adviser", NPR, July 12, 2005.

- 1 2 Wiley, Ed (November 9, 2006). "The 9/11 conspiracy: Rubbish or reality? – US news – Life – Race & ethnicity". MSNBC. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- 1 2 "Dick Gregory's Role as Michael Jackson's Adviser", NPR, July 12, 2005.

- 1 2 3 Porter, Tom (August 20, 2017). "Here's all you need to know about pioneering comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory, who has died aged 84". Newsweek. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Democracy Now, Amy Goodman, August 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Dick Gregory", Contemporary Black Biography. Encyclopedia.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "Obituary: Richard "Dick" Gregory died on August 19th". The Economist. September 7, 2017.

- ↑ Dick Gregory, AEI Speakers Bureau. Accessed December 11, 2007. "A track star at Sumner High School, Gregory earned an athletic scholarship in 1951 to Southern Illinois University at Carbondale and became the first member of his family to attend college."

- 1 2 Fields-White, Monée (August 19, 2017). "Comedian and Civil Rights Activist Dick Gregory Dead at 84". The Root. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Otfinoski, Steven (2014). African Americans in the Performing Arts. Infobase Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 1438107765.

- 1 2 3 Flash. "About – Dick Gregory Global Watch". dickgregory.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Dick Gregory – National Visionary", National Visionary Leadership Project.

- ↑ Saunders, Lonna (April 29, 2013). "Dick Gregory: "What I'm Running From" Bryn Mawr College Feb. 28". Huffington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ↑ Joke Gregory Told That Got Him Hired By High Hefner.

- ↑ Lutz, Phillip (February 19, 2010). "A Bit Slower, but Still Throwing Lethal Punch Lines". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 "Dick Gregory's Appearance on Arsenio PT. 2". YouTube. May 16, 2014. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- 1 2 Haberman, Clyde (August 19, 2017). "Dick Gregory, 84, Dies; Found Humor in the Civil Rights Struggle". New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- 1 2 Ernest Freeberg, "Inviting Controversy: When Tennessee Students Demanded Free Speech Rights, a Half Century Ago", Knoxville News Sentinel, September 7, 2017.

- ↑ G. Michel, Struggle for a Better South: The Southern Student Organization Committee, 1964-1969 (Springer 2004), p.183.

- ↑ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- 1 2 Haywood, Wil (August 24, 2000). "The Pain and Passion of Dick Gregory". Boston Globe. CommonDreams. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Hinckley, David (August 20, 2017). "How Dick Gregory Took Himself Off the Main Stage, and Why". Huffington Post. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Drucker, Michael (March 15, 2006). "Wonder Showzen: Season One". IGN. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Nguyen, Daisy (August 20, 2017). "Comedian, civil rights activist Dick Gregory dies". PBS. Associated Press. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Haggins, Bambi (2007). Laughing Mad: The Black Comic Persona in Post-soul America. Rutgers University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780813539850.

- ↑ "Civil Rights Icon Dick Gregory: The Social Engineers are Here to Divide and Conquer Us 1/4". The Alex Jones Channel. September 14, 2010. Retrieved August 20, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Obama: The Globalist Ultimate Puppet with Civil Rights Icon Dick Gregory". The Alex Jones Channel. March 19, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Secret Of Malaysia Flight 370: "Brain-Heist"". The Alex Jones Channel. April 1, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2017 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 Saunders, Lonna (February 27, 2013). "Dick Gregory: "What I'm Running From" Bryn Mawr College Feb. 28". The Huffington Post.

- ↑ "Listen, Whitey! The Sounds of Black Power 1967–1974", Light in the Attic Records.

- ↑ Semioli, Tom (October 30, 2013). "Listen to This Book: The Sights and Sounds of Black Power 1965–1975". The Huffington Post.

- ↑ "Off-Broadway Theatre Review: Turn Me Loose" by Tulis McCall, New York Theatre Guide, May 31, 2016

- ↑ Yes, The (June 19, 2011). "Journalist Lillian Smith with her mentor Human Rights Activist Dick Gregory. | Flickr – Photo Sharing!". Flickr. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ↑ Howard Zinn, You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train. Beacon Press, 1994; rev. ed. 2002, p. 58.

- ↑ Hart, Jeffrey (September 10, 1971). "Evonne Goolagong Plays Tennis in South Africa". New York Daily News.

- ↑ "How Dick Gregory Forced the FBI to Find the Bodies of Three Civil Rights Workers Slain in Mississippi". http://readersupportednews.org/. September 14, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- 1 2 "Dick Gregory, pioneering US comedian and activist, dies aged 84". The Guardian. Associated Press. August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Thompson, Hunter S. (1979) [1974]. The Great Shark Hunt. Gonzo Papers. 1. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 20. ISBN 0-7432-5045-1.

Hubert Humphrey lost that election by a handful of votes – mine among them – and if I had it to do again I would still vote for Dick Gregory.

- ↑ "People's Party Nominates Dr. Spock For President". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. November 29, 1971. pp. B5.

- ↑ "Spock, Gregory to Be on Ballot". Cape Girardeau Southeast Missourian. March 6, 1968. p. 10.

- ↑ "Our Campaigns - US President National Vote Race - Nov 05, 1968". ourcampaigns.com.

- ↑ "Our Campaigns – Political Party – Freedom & Peace (FPP)". ourcampaigns.com.

- ↑ Evans, Bradford (August 31, 2011). "8 Memorable Political Campaigns by Comedians". Splitsider. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ↑ Zapruder film on Good Night America – 3/6/75 Robert Groden and Dick Gregory on YouTube.

- ↑ Muhammad, Latifah (August 19, 2017). "Dick Gregory, Comedic Legend And Civil Rights Activist, Dead At 84". Vibe. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Eaton, Perry (May 24, 2017). "Long before Boston Calling, there was the Amandla Festival". Boston.com. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- 1 2 Dennis McLellahn (August 19, 2017). "Dick Gregory, who rose from poverty to become a groundbreaking comedian and civil rights activist, dies at 84". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ↑ "Clinton leads tribute to King". CNN. January 15, 1996. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Dick Gregory Talks About His Fight With Cancer". Jet. June 2000.

- ↑ "PETA Recruits Comedian, Activist in Anti-KFC Push," Nation's Restaurant News, November 24, 2003.

- ↑ Newsmax. "Newsmax.com – Breaking news from around the globe: U.S. news, politics, world, health, finance, video, science, technology, live news stream". newsmax.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Dick Gregory Blasts 'Insane, Racist System' in America". July 7, 2008.

- ↑ "WTC 1 and 2: Justice and 9/11 Demands Accountability. Forensic Evidence Indicates Presence of Controlled Demolition Material". GlobalResearch.ca. Montreal: Centre for Research on Globalisation. September 10, 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ "Dick Gregory, Funny, Blunt Civil Rights Advocate", African American Registry.

- ↑ Ebony, August 1985, p. 87.

- ↑ "The Dick Gregory Diet: Lose Weight Fast – Without Fasting – and Get (Him) Rich Quick", People archive, September 17, 1984, Vol. 22, No. 12.

- ↑ Company, Johnson Publishing (May 27, 1985). Jet. Johnson Publishing Company.

- ↑ "Caribbean Diet". Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Comedian and activist Dick Gregory dies at 84". ABC News. August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Mike Barnes (August 19, 2017). "Dick Gregory, Trailblazer of Stand-Up Comedy, Dies at 84". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Dick Gregory Album Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Dick Gregory Album Discography – Compilations". AllMusic. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dick Gregory |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dick Gregory. |

- SNCC Digital Gateway: Dick Gregory, Documentary website created by the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University, telling the story of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee & grassroots organizing from the inside-out

- Dick Gregory on IMDb

- Dick Gregory discography at Discogs

- Dick Gregory at AllMusic

- A short biography from www.dickgregory.com

- "Dick Gregory photographs". University of Missouri–St. Louis.

- Dick Gregory's oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Speech by Dick Gregory at San Francisco State College 1971. Audio recording from a broadcast on the radio

- Speech by Dick Gregory given on October 20, 1969. Audio recording from The University of Alabama's Emphasis Symposium on Contemporary Issues

- Footage of October 1968 interview with Dick Gregory regarding his candidacy for the Presidency in 1968

- Portrait of Dick Gregory at Americans Who Tell the Truth

- Kim Janssen, "When J. Edgar Hoover told Chicago FBI to set the Outfit on Dick Gregory", Chicago Tribune, August 22, 2017