High Speed 2

| High Speed 2 | |

|---|---|

Planned High Speed 2 route | |

| Overview | |

| Type | High-speed railway |

| System | National Rail |

| Status |

Planned for 2026 (Phase 1) and 2032–2033 (Phase 2) |

| Locale |

Phase 1: Greater London and West Midlands Phase 2: North West and Yorkshire Potential future phases: North East England and Scotland |

| Termini |

London Euston Phase 1: Birmingham Curzon Street and WCML connection near Rugeley Phase 2: Manchester Piccadilly and Leeds Potential future termini: Liverpool Lime Street, Newcastle, Edinburgh Waverley and Glasgow Central |

| Stations | 4 (Phase 1), 6 (Phase 2) |

| Technical | |

| Line length |

Phase 1: 140 miles (230 km); Phases 1 and 2: 330 miles (530 km)[1] |

| Number of tracks | Double track or Quadruple in some sections |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Loading gauge | GC |

| Electrification | 25 kV AC overhead |

| Operating speed | Up to 400 km/h (250 mph)[2] |

High Speed 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

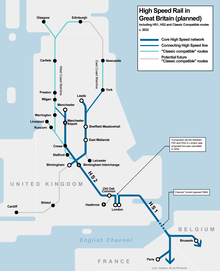

High Speed 2 (HS2) is a planned high-speed railway in the United Kingdom, directly linking London, Birmingham, the East Midlands, Leeds and Manchester.[3][4][5] Due to open in phases between 2026 and 2033, it will have 330 miles (530 km) of track, and high-speed trains will travel up to 400 km/h (250 mph). HS2 will be the second high-speed rail line in Britain, the first being High Speed 1 (HS1), which connects London to the Channel Tunnel, opened in the mid-2000s.

Peak hour capacity at the HS2 London terminal at London Euston will more than triple when network is fully operational, increasing from 11,300 to 34,900 passengers each way. The line is to be built in a "Y" configuration, with London at the bottom of the "Y", Birmingham at the centre, Leeds at the top right and Manchester at the top left. The two phases of the project will be:

- Phase 1 – from London to the West Midlands, with the first services scheduled for 2026.

- Phase 2 – from the West Midlands to Leeds and Manchester, scheduled for full completion by 2033.

Phase 2 is split into two sub-phases:

- Phase 2a – from the West Midlands to Crewe, with the first services scheduled for 2027.

- Phase 2b – from Crewe to Manchester, and from the West Midlands to Leeds, with the first services scheduled for 2033, however a one year delay has been announced to mesh in Northern Powerhouse rail, west to east line, into HS2.[6][7][3]

Services on the new routes will be provided by two fleets of trains: One dedicated only to the high-speed track, named "captive" trains, servicing Birmingham, Leeds, London and Manchester; the second fleet extends the reach of HS2 to cities on the existing "classic" network by operating on a mixture of high-speed track and existing tracks, named "classic compatible",[8] serving Carlisle, Chesterfield, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Liverpool, Newcastle, Preston, Sheffield and York.

HS2 is being developed by High Speed Two (HS2) Ltd, a company limited by guarantee established by the UK government. The project is estimated to cost £56 billion, up 71% on the initial projection in 2010 of £32.7 billion.[9] In July 2017, decisions on the full "Y" route were approved by Parliament.[3] Construction of Phase 1 began in 2017.[10]

History

High-speed rail arrived in the United Kingdom with the opening in 2003 of the first part of High Speed 1 (then known as the 108 km (67 mi) Channel Tunnel Rail Link) between London and the Channel Tunnel. The assessment of the case for a second high-speed line was proposed in 2009 by the DfT under the Labour government, which was to be developed by a new company, High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd).[11]

Following a review by the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition,[12] a route was opened to public consultation in December 2010.[13][14] based on a Y-shaped route from London to Birmingham with branches to Leeds and Manchester, as originally put forward by the previous Labour government,[15] with alterations designed to minimise the visual, noise, and other environmental impacts of the line.[13]

In January 2012 the Secretary of State for Transport announced that HS2 would go ahead in two phases and the legislative process would be achieved through two hybrid bills.[16][17] The High Speed Rail (London – West Midlands) Act 2017 authorising the construction of Phase 1 passed both Houses of Parliament and received Royal Assent in February 2017.[18] Phase 2a High Speed Rail (West Midlands – Crewe) bill seeking the power to construct Phase 2 up to Crewe and decisions on the remainder of the Phase 2b route was introduced in July 2017.[19]

Route

Phase 1 – London to the West Midlands

Phase 1 route will create a new high speed line between London and Birmingham by 2026. A high speed link will also be provided to the existing West Coast Main Line (WCML) just north of Lichfield in Staffordshire which will provide services to North West of England and Scotland, ahead of later phases.

Four stations will be included on the route: the London and Birmingham termini will be London Euston and Birmingham Curzon Street terminus station, with interchanges at Old Oak Common railway station and Birmingham Interchange respectively.

The route will exit London via a tunnel to West Ruislip from where it crosses the Colne Valley (including the M25) on a major viaduct, then a further tunnel under the Chilterns AONB to South Heath, north-west of Amersham. North of the second tunnel, the route will run roughly parallel to the existing A413 road and London to Aylesbury Line corridor, passing to the west of Wendover in a Cut-and-cover tunnel. After Aylesbury, the line will run alongside the Aylesbury–Verney Junction line, joining it north of Quainton Road and then striking out to the northwest across open countryside through North Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, South Northamptonshire, Warwickshire and Staffordshire terminating the phase at Lichfield with a connection onto the WCML. The line would be operative with trains moving onto the classic track WCML while Phase 2 is being built.

In November 2015, the then Chancellor, George Osborne, announced that the HS2 line would be extended to Crewe by 2027, reducing journey times from London to Crewe by 35 minutes. The section from Lichfield to Crewe is a part of Phase 2a planned to be built simultaneously with Phase 1, effectively merging Phase 2a with Phase 1. The proposed Crewe Hub incorporating a station catering for high-speed trains will be built as part of Phase 2a.[20]

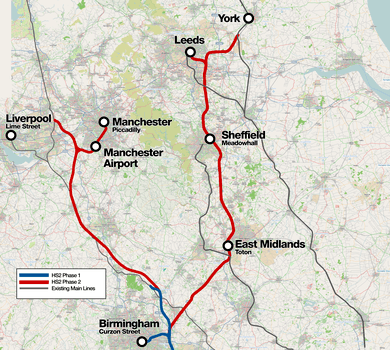

Phase 2 – West Midlands to Manchester and Leeds

In November 2016, Phase 2 plans were approved by the government with the route confirmed.[21][22] Phase 2 will create two branch lines from Birmingham running north either side of the Pennines creating a "Y" network. Phase 2 is split into two phases, 2a and 2b. Phase 2a is the section from Lichfield to Crewe on the western section of the "Y" and Phase 2b is the remainder of Phase 2.

- The western section:

- This section of the "Y" route extends north from Lichfield connecting to the northbound classic WCML at Bamfurlong south of Wigan taking services to Scotland, with a branch to the existing Manchester Piccadilly station. A branch onto the WCML at Crewe takes trains on classic track 64 km (40 mi) forty miles into Liverpool.

- The eastern section:

- This section of the "Y" branches at Coleshill to the east of Birmingham and routes north to just before York where it connects onto the northbound classic ECML projecting services to the North East of England and Scotland.

West Midlands to Crewe (Phase 2a)

This is an extension of the Phase 1 line that terminates north of Lichfield where it connects to the West Coast Main Line (WCML). The line will extend north to the proposed Crewe Hub. Opening a year after Phase 1, most of the construction will be parallel with Phase 1.

Crewe Hub (Phase 2a)

The Crewe Hub is an important addition to the HS2 network giving additional connectivity to existing classic lines radiating from Crewe junction. The benefits are:

- An updated station at Crewe to cope with high-speed trains.

- A tunnel under Crewe station to allow HS2 trains to by-pass the station remaining on HS2 tracks.

- A branch onto the WCML just to the south of Crewe station to allow trains to enter the station from the south.

- A branch onto the WCML just to the north of Crewe station to allow trains to enter the station from the north.

- Allows trains from the north and south to run off HS2 track onto classic lines splaying from the existing comprehensive junction.

- Allowing northbound trains to by-pass the station using the tunnel under the station and run onto the WCML north of the station.[23]

Crewe to Bamfurlong and Manchester (Phase 2b)

HS2 track continues north from Crewe with its end point at Bamfurlong south of Wigan where it branches into the WCML. As the line passes through Cheshire at Millington it will branch to Manchester using a triangular junction. The Manchester branch then veers east in a circuitous route around Tatton running past Manchester airport through a station at the airport, with the line then entering a 16-kilometre (10 mi) tunnel, emerging at Ardwick where the line will continue to its terminus at Manchester Piccadilly.

West Midland to ECML and Leeds (Phase 2b)

East of Birmingham the Phase 1 line branches at Coleshill progressing north east roughly parallel to the M42 motorway, progressing north between Derby and Nottingham the line ends by branching into the northbound ECML south of York, projecting services to the North East of England and Scotland on a mixture of HS2 and classic tracks.[24]

The line from Birmingham northeast bound incorporates the proposed East Midlands Hub located at Toton between Derby and Nottingham. The East Midlands Hub will serve Derby, Leicester and Nottingham. There will be a spur off the HS2 track to Chesterfield station and Sheffield station from a branch at Clay Cross onto the classic track Midland Main Line branching back onto HS2 track east of Grimethorpe. HS2 Ltd will fund the electrification of the Midland Main Line from Clay Cross to the east of Grimethorpe.[25] HS2 track will branch directly into a Leeds HS2 terminus.

The initial plan was for the line to serve Sheffield directly via a new raised station adjacent to Tinsley Viaduct, near to Meadowhall Interchange east of Sheffield as the line progresses north. This met with opposition from Sheffield Council, which lobbied for the line to be routed though Sheffield city centre. As a result, Sheffield will be accessed via a spur using existing classic tracks, to the benefit of Chesterfield which will have a HS2 classic compatible service.[26][27][28][29][30]

A branch will take the HS2 line to new high speed platforms constructed onto the side of the existing Leeds station.[31][32][33] Completion is scheduled for 2033.

Possible South Yorkshire Hub

Changes were made to the eastern leg of the HS2 "Y" route through South Yorkshire with Meadowhall on the outskirts of Sheffield being dropped from the scheme. The city of Sheffield will be served directly to its city centre at Sheffield Midland station via the Midland Main Line classic track. A spur will be created by a branch off the main HS2 track at Clay Cross onto the Midland Main Line via Chesterfield. HS2 will branch back onto HS2 track east of Grimethorpe north of Sheffield.

There are suggestions for a new 'South Yorkshire Hub' station to be built to replace Meadowhall. However the current plans have no firm plans. The proposal is a future hub near Thurnscoe, Rotherham or Dearne Valley.[34][35] The plans were backed by Sir David Higgins, head of HS2 Ltd, in December 2016 and would see a new South Yorkshire Parkway Station.[36]

The Transport Document, released in July 2016, stated:

- As mentioned above, I also believe that HS2 should carry out a study to make recommendations to the Secretary of State on the potential for a parkway station on the M18/Eastern leg route which could serve the South Yorkshire area as a whole.

In January 2017, the government published 8 possible sites for the hub across South Yorkshire and also said they would consider a 'South Yorkshire Hub'.[37]

Sites being considered include: Bramley in Rotherham, South Yorkshire, Clayton in Doncaster, South Yorkshire, Fitzwilliam in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, Hemsworth in Wakefield, Hickleton in Doncaster, Hooton Roberts in Rotherham, Mexborough in Doncaster and Wales in Rotherham.

In July 2017, MPs called for the government to build a parkway station on the planned HS2 route through South Yorkshire after the government confirmed the HS2 Route would be the M18 Eastern Route. Transport Secretary, Chris Grayling confirmed in a letter to MP John Healey, the MP for Wentworth and Dearne, that a parkway station in South Yorkshire is ongoing and that Grayling and the other local MP's were pushing for the case of a station.[38]

In September 2017, leaders called for a station in South Yorkshire, while HS2 Ltd said any new station would require a consultation and that they were still assessing the 8 sites proposed in January 2017. Any new station would have to be near to the existing railway lines in order to provide the best benefits of HS2.[39]

In December 2017, the chairman of HS2 ordered a decision on the HS2 parkway station in South Yorkshire to made soon and also confirmed that only 3 options were being assessed. The decision will need to be made before a final decision in Parliament is made in 2019.[40]

Possible future phases – Liverpool/Newcastle/Scotland

There are no DfT proposals to extend high-speed lines north of Leeds to Newcastle or Scotland or west of Manchester to Liverpool. High-speed trains will be capable of accessing some destinations off the high-speed lines using the existing classic rail tracks.

Liverpool

Taking HS2 directly to Liverpool on high-speed track may be accommodated via Northern Powerhouse Rail (HS3). A House of Commons Briefing Paper, Number CBP07082, 15 November 2016, High Speed 2 (HS2) Phases 2a, 2b and beyond, states:

- "TfN has examined two options that make use of HS2 to connect Manchester and Liverpool. Both options involve construction of a new line to Liverpool, and a junction onto the HS2 route. Under these options it would be possible to deliver NPR's ambitions for a 30 minute journey between Manchester and Liverpool, connecting the cities via Manchester Airport"[41]

A "passive provision", which is a small section of additional HS2 track, would enable the future construction of Northern Powerhouse Rail (HS3) to link to the HS2 network without disrupting HS2 services once they are running. This will be provided for in the Hybrid Bill.[42] However, as yet there is no firm commitment to a direct HS2 link into Liverpool.

The city of Liverpool which was omitted from the HS2 scheme, in February 2016 offered £2 billion towards funding a direct HS2 line into Liverpool's city centre. The nearest HS2 track is 16 miles (26 kilometres) from the city.[43]

Newcastle

The Scottish Partnership Group for High Speed Rail in June 2011 campaigned for the extension of the HS2 to Newcastle.[44]

Scotland

In Scotland, business and governmental organisations including Network Rail, CBI Scotland and Transport Scotland (the transport agency of the Scottish Government) formed the Scottish Partnership Group for High Speed Rail in June 2011 to campaign for the extension of the HS2 project north to Edinburgh and Glasgow. It published a study in December 2011 which outlined a case for extending high-speed rail to Scotland, proposing a route north of Manchester to Edinburgh and Glasgow as well as an extension to Newcastle.[44]

In 2009, the then Transport Secretary Lord Adonis outlined a policy for high-speed rail in the UK as an alternative to domestic air travel, with particular emphasis on travel between the major cities of Scotland and England. "I see this as the union railway, uniting England and Scotland, north and south, richer and poorer parts of our country, sharing wealth and opportunity, pioneering a fundamentally better Britain," he stated in his speech.[45]

In November 2012 the Scottish Government announced plans to build a 74 km (46 mi) high-speed rail link between Edinburgh and Glasgow. The proposed link would have reduced journey times between the two cities to under 30 minutes and was planned to open by 2024, eventually connecting to the high-speed network being developed in England.[46] The plan was cancelled in 2016.[47]

In May 2015, it was reported that HS2 Ltd has concluded that there was "no business case" to extend HS2 north into Scotland, and that high-speed rail services would run north of Manchester and Leeds on conventional classic track.[48]

Greengauge 21 at the National HSR Conference in Glasgow in September 2015 recommended a mixture of high-speed and existing classic track to Scotland to reduce journey times. This would use planned HS2 track, existing WCML track and sections of newly laid high-speed track.[49]

In July 2016 it was reported that the 400-metre-long HS2 trains using the existing classic track will not be accommodated at Glasgow Central or Glasgow Queen Street stations, due to insufficient space to extend the platforms. Extended or new platforms would require compulsory purchase of buildings and land. Instead, the proposals suggested a possible third major station in Glasgow.[50]

Proposals to extend HS2 to Scotland via the East Coast have included plans for a new station outside of York. This station could be built on the A59, the A64, outer ring road or Harrogate to York railway line.[51]

Connection to other lines

Existing main lines

A key feature of the HS2 proposals is that the new lines will include connections to existing, standard-speed classic main lines. It is proposed that these connections will allow the running of special "classic compatible" trains which are capable of operating on both high-speed lines (at the same speed as "captive" trains) and on "classic" lines at speeds of 200 km/h (120 mph) or below. This will enable trains to run to destinations served only by slower classic tracks, such as Liverpool, Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Newcastle, using a combination of slower "classic" and faster "high-speed" track. As HS2 trains are non-tilting they will be slower than existing tilting trains on some sections of classic tracks. The proposed connections will be at junctions on the phase-2 network at the following locations:[52]

- east of Lichfield Trent Valley, 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) northwest of Lichfield

- north of Crewe

- south of Crewe

- south of Wigan North Western

- at Ulleskelf 8 km (5 mi) southeast of York, joining the existing Church Fenton line 3 km (2 mi) north of that the line meets the East Coast Main Line at Colton Junction near Colton, North Yorkshire.[24]

The route to the West Midlands will be the first stage of a line to Scotland,[53] and passengers travelling to or from Scotland will be able to use through trains using a mixture of high-speed and classic tracks with a saving of 45 minutes from day one.[54] It was recommended by a Parliamentary select committee on HS2 in November 2011 that a statutory clause should be in the bill that will guarantee HS2 being constructed beyond Birmingham so that the economic benefits are spread farther.[55]

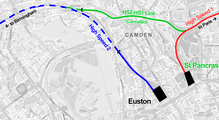

High Speed 1

The Department for Transport initially outlined plans to build a two-kilometre-long (1.2 mi) link between HS2 and the existing High Speed 1 line that connects London to the Channel Tunnel. At their closest points, the two high-speed lines will be only 640 m (0.4 mi) apart. This connection would have enabled rail services running from Manchester, Leeds and Birmingham to bypass London Euston and to run directly to Paris, Brussels and other continental European destinations, realising the aims of the Regional Eurostar scheme that was first proposed in the 1980s.[56][57] Several schemes were considered, and the route finally put forward was a tunnel between Old Oak Common and Chalk Farm, linked to existing "classic speed" lines along the North London Line which would connect to HS1 north of St Pancras.[58][59][60][61]

Concerns were raised by Camden London Borough Council about the impact on housing, Camden Market and other local businesses from construction work and bridge widening along the proposed railway link.[62][63] Alternative schemes were considered, including boring a tunnel under Camden,[64] but the HS1-HS2 link was removed from the parliamentary bill at the second reading stage in order to save £700 million from the budget.[65]

HS3

High Speed 3 (HS3), a high-speed railway across the North of England was proposed in 2015 by Transport for the North (TfN). The east-west trans-Pennine railway line would provide a high-speed link between northern cities such as Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield, Newcastle and Hull, with connections to HS2. In March 2016 The National Infrastructure Commission's report, "High Speed North", recommended collaboration between TfN and HS2 Ltd. on the design of the northern parts of HS2. Some redesigning would be needed of HS2 to link into HS3.[66] The HS3 rail link was given the go-ahead in the March 2016 budget.[67] The Institute of Public Policy Research on 8 August 2016 urged the government to prioritise HS3 over HS2.[68] Sir David Higgins, head of HS2, explained the collaboration between HS3 and HS2 in a Parliamentary Select Committee in December 2016. He outlined potential schemes being considered for a high-speed connection between Liverpool and Manchester, including a link via Golborne or a southern route via Manchester Airport into Piccadilly station.[69]

HS4Air

In 2018 a proposal was put forward by a British engineering consultancy, Expedition Engineering, for HS4Air, a high-speed railway line that would connect HS2 to HS1 via a 140-kilometre (87 mi) route running to the south of Greater London via Heathrow and Gatwick Airports. The scheme is currently at the proposal stage and has not been endorsed by government.[70]

Planned stations

London and Birmingham

Central London

HS2 will start from a rebuilt London Euston. The station will be extended to the south and west with significant construction above. Twenty-four platforms will serve High Speed and classic lines to the Midlands, with six underground lines. The connection with Crossrail at Old Oak Common in West London is designed to mitigate the extra burden on Euston, although Euston too would see its underground station rebuilt and integrated with Euston Square.[71][72] A rapid transit "people mover" link between Euston and St Pancras might be provided[73] and it is proposed to route the proposed Crossrail 2 (Chelsea–Hackney line) via Euston to cope with increased passenger demand.[74][75]

A review by Lord Mawhinney suggested that HS2 should terminate at Old Oak Common, not Euston.[76] He questioned the sense of HS2 terminating at Euston, with HS1 at St Pancras and no through running connection between them.[76] The plans proposed a link via an upgraded section of the North London Line to enable three trains per hour to run through to High Speed 1 and towards the Channel Tunnel, bypassing Euston.[71]

West London

A report published in March 2010 proposed that all trains would stop at a "Crossrail interchange" near Old Oak Common, between Paddington and Acton Main Line, with connections for Crossrail, Heathrow Express, and the Great Western Main Line to Heathrow Airport, Reading, South West England and South Wales. The station might also have interchange with London Overground and Southern on the North London and West London Lines and also with London Underground's Central line.[77]

Mawhinney recommended that HS2 should terminate at Old Oak Common because of its good connections and to save the cost of tunnelling to Euston.[76] The HS2 route published on 10 January 2012 included stations at both Euston and Old Oak Common.[78]

Birmingham Interchange

The March 2010 report proposed that a new Birmingham Interchange through station in rural Solihull, on the east side of the M42 motorway from the National Exhibition Centre, Birmingham International Airport and the existing Birmingham International Station.[79]

The station will be located at a separate site from the existing Birmingham International Station. Passengers will interchange via a people mover between the stations and the other sites, with a capacity of over 2100 passengers per hour in each direction in the peak period.[80] The AirRail Link people mover already operates between Birmingham International station and the airport.

Birmingham Airport's chief executive Paul Kehoe stated that HS2 is a key element in increasing the number of flights using the airport, with added patronage by inhabitants of London and the South East, as HS2 will reduce travelling times to Birmingham Airport from London to under 40 minutes.[81]

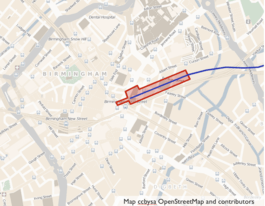

Birmingham city centre

A new terminus for HS2, termed "Birmingham Curzon Street" in the government's command paper[82] and "Birmingham Fazeley Street" in the report produced by High Speed 2 Ltd, would be built on land between Moor Street Queensway and the site of Curzon Street station. It would be reached via a spur line from a triangular junction with the HS2 main line at Coleshill.[83]

The planned site for the new station is immediately adjacent to Moor Street station, and approximately 400 metres (0.25 mi) northeast of New Street station. Passenger interchange with Moor Street would be at street level, across Moor Street Queensway; interchange with New Street would be via a pedestrian walkway between Moor Street and New Street (opened in 2013).[84][85][86] The other city-centre station, Snow Hill, is a couple of minutes' train journey from Moor Street.

Development planning for the Fazeley Street quarter of Birmingham has changed as a result of HS2. Prior to announcement of the HS2 station, Birmingham City University had planned to build a new campus in Eastside.[87][88] The proposed Eastside development will now include a new museum quarter, with the original stone Curzon Street station building becoming a new museum of photography, fronting on to a new Curzon Square, which will also be home to Ikon 2, a museum of contemporary art.[89]

Birmingham to Manchester (Phases 2a and 2b)

Proposals for the station locations were announced on 28 January 2013.

Birmingham to Crewe (Phase 2a)

HS2 will pass through Staffordshire and Cheshire. The line will run in a tunnel under the Crewe junction by-passing the station.[90] However, the HS2 line will be linked to the West Coast Main Line via a grade-separated junction just south of Crewe, enabling "classic compatible" trains exiting the high-speed line to call at the existing Crewe station.[91][92] In 2014, the chairman of HS2 advocated a dedicated hub station in Crewe.[93] In November 2015 it was announced that the Crewe hub completion would be brought forward to 2027.[94] In November 2017 the government and Network Rail supported a proposal to build the hub station on the existing station site, with a junction onto the West Coast Main Line north of the station. This will enable through trains to bypass the station via a tunnel under the station and run directly onto the WCML.[23]

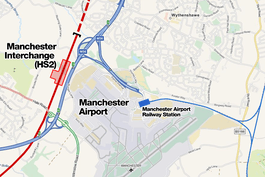

Manchester Airport (Phase 2b)

An HS2 station provisionally named Manchester Interchange is planned to the south of the city of Manchester, serving Manchester Airport. It was recommended in 2013 by local authorities during the consultation stage. Construction will be part-funded by private investment from the Manchester Airports Group.[96][97]

The proposed site is located on the northwestern side of the airport, to the west of the M56 motorway at junction 5, and approximately 2.4 km (1.5 mi) northwest of the existing Manchester Airport railway station. A sub-surface station is planned, approximately 8.5m below ground level, consisting of two central 415m platforms, a pair of through tracks for trains to pass through the station without stopping, a street-level passenger concourse and a main entrance on the eastern side, facing the airport.[98]

Current proposals do not detail passenger interchange methods; various options are being considered to integrate the new station with existing transport networks, including extending the Manchester Metrolink Airport Line to connect the HS2 station with the existing airport railway station.[99][100][101][102]

If the station is built, it is estimated that the average journey time from London Euston to Manchester Airport would be 59 minutes.[103]

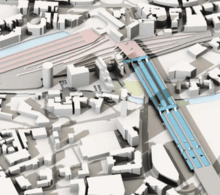

Manchester city centre (Phase 2b)

The route will continue from the airport into Manchester city centre via a 12.1-kilometre (7.5 mi) twin bore branch tunnel under the dense urban districts of south Manchester before surfacing at Ardwick.[104][105][106] If built, it will represent one of the major engineering feats of HS2 and will be the longest rail tunnel to be built in the United Kingdom, surpassing the 10.0-kilometre (6.2 mi) High Speed 1 tunnel completed in 2004.[107] The 12.2 km (7.6 mi) twin-bore tunnel will be at an average depth of 33 m (108 ft) and trains will travel through it at 228 kilometres per hour (142 mph). The diameter of the tunnel is dependent on the train speed and length of the tunnel.[108] It is envisaged both tunnels will be, as an "absolute minimum", at least 7.25 metres (23 ft 9 in) in diameter to accommodate the high-speed trains.[109]

Up to 15 sites were put forward, including Sportcity, Pomona Island, expanding Deansgate railway station and re-configuring the grade-II listed Manchester Central into a station.[110] Three final sites made the long list: Manchester Piccadilly station, Salford Central station and a newly built station at Salford Middlewood Locks.[111] Three approaches were considered, one via the M62, one via the River Mersey and the other through south Manchester. Both Manchester and Salford city councils recommended routing High Speed 2 to Manchester Piccadilly, although the station throat faces southeast away from the incoming HS2 line, to maximise economic potential and connectivity rather than building a new station at a greater cost.[112]

HS2 will terminate at an upgraded Manchester Piccadilly station.[90] At least four new 400-metre-long (1,300 ft) platforms will be built to accommodate the new high-speed trains in addition to the two platforms which are currently planned as part of the Northern Hub proposal.[97] It is envisaged Platform 1 under the existing listed train shed will also be converted to a fifth HS2 platform. The HS2 concourse will be connected to the existing concourse at Piccadilly. HS2 will reduce the average journey time from central Manchester to central London from 2 hours 8 minutes to 1 hour 8 minutes.

Birmingham to Leeds (Phase 2b)

HS2 will reduce the average journey time from central Leeds to London from 2 hours 20 minutes to 1 hour 28 minutes.

East Midlands Hub

HS2, to serve the East Midlands has planned a new through station named the East Midlands Hub located at Toton sidings west of Nottingham. The station will be an out of town parkway station,[note 1] serving the cities of Nottingham, Derby and Leicester.[113] The Derbyshire and Nottingham Chamber of Commerce supports high-speed rail serving the East Midlands, however was concerned that a parkway station instead of centrally located stations in each of the three cities would result in no overall net benefit in journey times.[113] Their concerns are based on the East Midlands Parkway railway station that was recently constructed on the Midland Main Line south of Derby and Nottingham, close to the proposed HS2 site in Toton, which is failing to reach its passenger targets by a substantial margin.[114]

Removal of Sheffield from direct HS2 service

HS2 continues north passing Sheffield to the east of the city. Initially there were plans for a direct Sheffield Meadowhall HS2 station, located close to the existing Meadowhall Interchange east of the city. After petitioning by Sheffield City Council the route to the city was changed on 7 July 2016 with high-speed trains serving the centre of the city using classic compatible trains. High-speed trains would branch off HS2 track onto existing classic track south of Sheffield at Clay Cross, north through and serving Chesterfield station and continuing north into Sheffield station. High-speed trains can leave Sheffield and Chesterfield heading north and then branch back onto HS2 track north of the city at Grimethorpe.[26][27]

The proposed city centre station would, according to Sheffield City Council, generate up to £5 billion more for the local economy than a station at Meadowhall, whilst also increasing the station's usage and creating around 6,500 extra jobs, while a Meadowhall station would cause problems with road congestion.[115][116]

Leeds

HS2 continues north after the branch at Grimethorpe through West Yorkshire toward York, with a spur taking the line into Leeds. It was originally proposed that a separate HS2 station – Leeds New Lane – would be built.[24] However, a later review decided that greater benefits would be obtained by bringing HS2 to the existing Leeds station. HS2 platforms will be built onto the Southern side of the station building creating a common concourse for easy interchange between high speed and classic rail services.[33]

Operation

Proposed service pattern

HS2 will provide up to 18 trains an hour by 2033 to and from London.[3] As of 2018 the service pattern is yet to be defined; the assumptions used in the modelling in the Department for Transport's economic case for HS2, updated for Phase 2, used the following service pattern:[117]

Phase One

| Start | Destination | Trains per hour | Intermediate stations |

|---|---|---|---|

| London Euston | Birmingham Curzon Street | 3 | Old Oak Common (OOC), Birmingham Interchange |

| Birmingham Interchange | 3 | OOC | |

| Liverpool Lime Street | 2 | OOC, Stafford (1tph), Crewe (1tph), Runcorn | |

| Manchester Piccadilly | 3 | OOC, Wilmslow (1tph), Stockport | |

| Preston | 1 | OOC, Crewe, Warrington Bank Quay, Wigan North Western | |

| Glasgow | 1 | OOC, Preston |

Phase Two

| Start | Destination | Trains per hour | Intermediate stations |

|---|---|---|---|

| London Euston | Curzon Street | 3 | Old Oak Common and Birmingham Interchange (2tph) |

| Manchester Piccadilly | 3 | Old Oak Common, Birmingham Interchange (1tph) and Manchester Airport (2tph) | |

| Liverpool Lime Street | 2 | Old Oak Common, Birmingham Interchange, Stafford (1tph), Crewe (1tph) and Runcorn | |

| Preston | 1 | Old Oak Common, Warrington Bank Quay and Wigan North Western | |

| Glasgow Central | 2 | Old Oak Common, Birmingham Interchange (1tph), Preston and Carstairs | |

| Edinburgh | 2 | Old Oak Common, Birmingham Interchange (1tph), Preston, Carstairs and Edinburgh Haymarket | |

| Leeds | 3 | Old Oak Common, Birmingham Interchange, East Midlands Hub (1tph), Chesterfield (1tph) Sheffield Midland (1tph) | |

| Sheffield Midland | 2 | Old Oak Common, Birmingham Interchange, East Midlands Hub and Chesterfield (1tph) | |

| York | 1 | Old Oak Common & East Midlands Hub | |

| Newcastle | 2 | Old Oak Common (1tph), Birmingham Interchange and York | |

| Birmingham Interchange | Curzon Street | 1 | No intermediate stops |

| Liverpool Lime Street | 2 (per day) | Crewe and Runcorn | |

| Curzon Street | Stafford | 0.5 | No intermediate stops |

| Crewe | 0.5 | No intermediate stops | |

| Manchester Piccadilly | 1 | Crewe and Manchester Interchange | |

| Liverpool Lime Street | 2 | Crewe (1tph) and Runcorn | |

| Preston | 2 (per day) | Crewe, Manchester Interchange and Wigan North Western | |

| Carlisle | 2 (per day) | Manchester Interchange, Wigan North Western and Preston | |

| Glasgow Central | 1 | Warrington Bank Quay, Wigan North Western, Preston and Carlisle | |

| Edinburgh | 1 | Crewe, Warrington Bank Quay, Wigan North Western, Preston and Carlisle | |

| Sheffield Midland | 1 | East Midlands Hub and Chesterfield (3tph) | |

| Leeds | 1 | East Midlands Hub | |

| York | 1 | East Midlands Hub and Sheffield Midland (2tph) | |

| Newcastle | 1 | York | |

| Stafford | Crewe | 1 (per day) | No intermediate stops |

| Liverpool Lime Street | 1 | Runcorn | |

| Crewe | Liverpool Lime Street | 1 | Runcorn |

| Manchester Piccadilly | 1 | Manchester Interchange | |

| Glasgow Central | 1 | Warrington Bank Quay, Wigan North Western, Preston and Carlisle | |

| Manchester Interchange | Preston | 1 | Wigan North Western |

| Glasgow Central | 0.5 | Wigan North Western, Preston and Carlisle | |

| Edinburgh | 0.5 | Preston and Carlisle | |

| Preston | Glasgow Central | 1 | Carlisle |

| Carlisle | Glasgow Central | 1 | No intermediate stops |

| York | Newcastle | 1 | No intermediate stops |

Operator

Services on High Speed 2 will be included in the new West Coast Partnership franchise, which will replace the existing InterCity West Coast franchise upon its expiry in September 2019. The chosen operator will be responsible for running all aspects of the service including ticketing, trains and the maintenance of the infrastructure.[118] Three joint ventures were shortlisted by the Department for Transport in June 2017 and tendered their bids for the new franchise in March 2018:[119][120]

- First Trenitalia West Coast Rail Ltd, a joint venture between FirstGroup and Trenitalia

- MTR West Coast Partnership Ltd, a joint venture between MTR Corporation and Guangshen Railway Company

- West Coast Partnership Ltd, a joint venture between Stagecoach Group, Virgin Group and SNCF.

The new franchise will run for the first five years of HS2's operation.[120][121][122][123] The Government has not ruled out the possibility of open access operators.[124][125][126]

Fares

There has been no announcement about how HS2 tickets will be priced, although the government said that it would "assume a fares structure in line with that of the existing railway" and that HS2 should attract sufficient passengers to not have to charge premium fares.[127] Paul Chapman, in charge of HS2's public relations strategy, suggested that there could be last minute tickets sold at discount rates. He said, "when you have got a train departing on a regular basis, maybe every five or ten minutes, in that last half hour before the train leaves and you have got empty seats...you can start selling tickets for £5 and £10 at a standby rate."[128]

Capacity

| Slow commuter | 3,900 | 6,500 | |

| Fast commuter | 1,600 | 6,800 | |

| Intercity | 5,800 | 1,800 | |

| High speed | 0 | 19,800 | |

| Total | 11,300 | 34,900 |

HS2 will carry up to 26,000 people per hour,[16] with anticipated annual passenger numbers of 85 million.[131] The line will be used intensively with 15 trains per hour travelling to and from Euston. As all trains will be travelling at the same speed, capacity is increased as faster trains have no need to reduce speed for slower trains. The line is only for high speed passenger trains eliminating slow freight and commuter trains. Moving high speed trains off the West Coast Main Line, East Coast Main Line and Midland Main Line will release capacity for slower commuter trains. Andrew McNaughton, Chief Technical Director, said, “Basically, as a dedicated passenger railway, we can carry more people per hour than two motorways. It’s phenomenal capacity. It pretty much triples the number of seats long-distance to the North of England.”[132]

Infrastructure

The Department for Transport report on High Speed Rail published in March 2010 sets out the specifications for a high-speed line. It will be built to a European structure gauge (as was HS1) and will conform to European Union technical standards for interoperability for high-speed rail.[133] HS2 Ltd's report assumed a GC structure gauge for passenger capacity estimations,[134] with a maximum design speed of 400 kilometres per hour (250 mph).[2] Initially, trains would run at a maximum speed of 360 kilometres per hour (225 mph).[135]

Signalling would be based on the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) with in-cab signalling, to resolve the visibility issues associated with lineside signals at speeds over 200 kilometres per hour (125 mph). Platform height will be at the European standard of 760 millimetres (2 ft 6 in).[136]

The new line would release capacity for freight and more local, regional and commuter services and new direct services on both the West Coast Main Line, East Coast Main Line and Midland Main Line.[137]

Rolling stock

The rolling stock for HS2 has not yet been specified in any detail. Bidding for the contract to design and build the trains was opened in 2017 and is expected to be awarded in 2019. There will be 60 trains for Phase 1, each capable of seating 1,000 passengers.[138]

The 2010 DfT government command paper outlined some requirements for the train design among its recommendations for design standards for the HS2 network. A photograph of a French AGV (Automotrice à grande vitesse) was used as an example of the latest high-speed rail technology. The paper addressed the particular problem of designing trains to continental European standards, which use taller and wider rolling stock, requiring a larger structure gauge than the rail network in Great Britain.

The report proposed the development of two new types of train to make best use of the line:[135]

- Wider and taller trains built to a European loading gauge, which would be confined to the high-speed network (including HS1 and HS2) and other lines cleared to their loading gauge.

- 'Classic compatible' trains, capable of high speed, however built to a British loading gauge permitting the trains to leave the high-speed track to join conventional classic routes such as the West Coast Main Line, Midland Main Line and East Coast Main Line.[note 2] Such trains would allow running of HS2 services to the north of England and Scotland. However these non-tilting trains will run slower than existing tilting trains on classic track. HS2 Ltd has stated that, because these trains must be specifically designed for the British network and cannot be bought "off-the-shelf", these classic-compatible trains were expected to be around 50% more expensive, costing around £40 million per train rather than £27 million for the captive stock.[139]

Both types of train would have a maximum speed of at least 350 km/h (220 mph) and length of 200 metres (660 ft). Two units could be joined together for a 400-metre (1,300 ft) train.[135] It has been reported that these longer trains would have approximately 1,100 seats with Andrew McNaughton, technical director of HS2 stating "family areas will alleviate the stress of parents worried that their children are annoying other passengers who are maybe trying to work."[140]

The DfT report also considered the possibility of 'gauge clearance' work on non-high-speed lines as an alternative to 'classic compatible' trains. This work would involve extensive reconstruction of stations, tunnels and bridges and widening of clearances to allow European-profile trains to run beyond the high-speed network. The report concluded that although initial outlay on commissioning new rolling stock would be high, it would cost less than the widespread disruption of rebuilding large tracts of Britain's rail infrastructure.[135]

Alstom, one of the bidders for the contract to build the trains, proposed in October 2016 tilting HS2 trains to run on HS2 and classic tracks to increase overall speeds when running on classic tracks.[141][142]

Running costs

The estimated cost of power for running HS2 trains is as follows[143]

| On HS2 | 3.90 | 3.90 | 5.00 | |

| On classic network | n/a | 2.00 | 2.60 |

Maintenance depots

Rolling stock

A depot will be built in Washwood Heath, Birmingham, covering all of Phase 1 and Phase 2a.[144] In July 2018, the Transport Secretary, Chris Grayling, announced that the maintenance depot for the eastern leg of Phase 2b would be located at Gateway 45 near to the M1 motorway in Leeds.[145][146]

Infrastructure maintenance

In April 2010 Arup was asked to develop proposals for the location, engineering specification and site layout of the Infrastructure Maintenance Depot (IMD). The general location of the IMD was identified as adjacent to, or within 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) of the intersection of HS2 and the East West Rail (EWR) route near Steeple Claydon/Calvert in Buckinghamshire. The feasibility of using the MoD site at Bicester as the IMD was also considered. Six potential sites were shortlisted and rated against the specification. The preferred site, called "Thame Road" (at Claydon Junction), and a fall-back site, "Great Pond" were announced in December 2010.[147] The nearby Calvert Waste Plant has also been identified for heat and power generation.[147]

Journey times

From London

To HS2 stations

The DfT's latest revised estimates of journey times for some major destinations once the line has been built as far as Leeds and Manchester, set out in the January 2012 document High Speed Rail: Investing in Britain's Future – Decisions and Next Steps, are as follows:[148] Times given for Manchester and Leeds until completion of Phase 2b will be on a mixture of HS2 and classic track.

| London to/from | Fastest journey time before HS2

(hrs:min) |

Journey time after HS2 Phase 1 [149]

(hrs:min) |

Journey time after HS2 Phase 2

(hrs:min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birmingham | 1:13[t 1] | 0:49 | no change |

| East Midlands Hub | N/A | N/A | 0:51 |

| Manchester | 2:00[t 2] | 1:40 | 1:08 |

| Leeds | 1:59[t 3] | no change | 1:28 |

- ↑ Birmingham: one train per day, in one direction only: 07:30 New Street-08:43 Euston, standard journey times are 1:24

- ↑ Manchester: one train per day, in one direction only: 07:00 Piccadilly-09:00 Euston, standard journey times are 2:08

- ↑ Leeds: one train per day, in one direction only: 07:00 Leeds-08:59 King's Cross, standard journey times are 2:20

To other stations

| London to/from | Journey time before HS2

(hrs:min) |

Journey time after HS2 Phase 2[150][151]

(hrs:min) |

|---|---|---|

| Chesterfield | 1:49 | 1:15 |

| Crewe | 1:30 | 0:55 |

| Edinburgh | 4:23 | 3:38 |

| Glasgow | 4:32 | 3:38 |

| Liverpool | 2:08 | 1:36 |

| Newcastle | 2:52 | 2:19 |

| Preston | 2:08 | 1:24 |

| Sheffield | 2:05 | 1:19 |

| York | 1:53 | 1:23 |

From Birmingham

| Birmingham to/from | Journey time before HS2

(hrs:min) |

Journey time after HS2 Phase 2 [150][152]

(hrs:min) |

|---|---|---|

| Chesterfield | 1:00 | 0:45 |

| East Midlands Hub | N/A | 0:19 |

| Edinburgh | 4:01 | 3:14 |

| Glasgow | 4:08 | 3:38 |

| Leeds | 1:58 | 0:57 |

| Manchester Airport | 1:44 | 0:32 |

| Manchester | 1:28 | 0:41 |

| Newcastle | 3:14 | 2:07 |

| Preston | 1:31 | 0:53 |

| Sheffield | 1:03 | 0:48 |

| York | 2:10 | 1:03 |

Funding

The Department for Transport initially estimated the cost to be £30 billion to be funded by the government with the Manchester Airport station locally funded. The Manchester airport station is to be separately funded by the airport and the wider region.[153] Cost estimates have gradually risen since the first figures were released. The City of Liverpool, omitted from direct HS2 access, may add a third source of funding. In March 2016 the city offered £6 billion to fund a link from the city to the HS2 backbone 20 miles (32 kilometres) away.[154] HS2 received funding from the European Union's Connecting Europe Facility.[155]

The first 190-kilometre (120 mi) section, from London to Birmingham, was originally costed at between £15.8 and £17.4 billion,[156] and the entire Y-shaped 540-kilometre (335 mi) network at £30 billion.[156]

Upgrading existing lines from London to Birmingham instead of building HS2 would cost more (£20 billion) and would provide only two-thirds the extra capacity of HS2, according to Lord Adonis.[157]

In June 2013 the projected cost rose by £10 billion to £42.6 billion[158] and, less than a week later, it was revealed that the DfT had been using an outdated model to estimate the productivity increases associated with the railway.[159] Peter Mandelson, a key advocate when a study was undertaken of HS2 when the Labour Party was in government, declared shortly thereafter that HS2 would be an "expensive mistake",[160] and also admitted that the inception of HS2 was "politically driven" to "paint an upbeat view of the future" following the financial crash of 2008. He further admitted that the original cost estimates were "almost entirely speculative" and that "[p]erhaps the most glaring gap in the analysis presented to us at the time were the alternative ways of spending £30bn."[161] The then mayor of London, Boris Johnson, similarly warned that the costs of the scheme would be in excess of £70 billion.[162] The Institute of Economic Affairs estimates that the final cost will be over £80 billion.[163]

The link between HS1 and HS2 was dropped on cost grounds.[164] In April 2016 Sir Jeremy Heywood, a top UK civil servant, was reviewing the HS2 project to trim costs and gauge whether the now £55 billion project could be kept within budget.[165][166]

Perspectives

New political and financial dynamics

Until the start of the Great Recession, high-speed rail did not feature high among the priorities of British policy makers and institutional investors: “Britain’s best rail transport network, the High-Speed 1 line (HS1 or ‘Channel Tunnel Rail Link’) connecting the country to Paris, [is] a strategic infrastructure asset designed by French engineers, and owned and operated by Canadian pension funds.”[167] However, policy attitudes towards modern transport infrastructure started to change in the early 2010s, notably with renewed interest for the notion of UK pension investment in domestic infrastructure projects jointly with the state.[168]

Government rationale

A 2008 paper, 'Delivering a Sustainable Transport System'[169] identified fourteen strategic national transport corridors in England, and described the London – West Midlands – North West England route as the "single most important and heavily used" and also as the one which presented "both the greatest challenges in terms of future capacity and the greatest opportunities to promote a shift of passenger and freight traffic from road to rail".[170] They noted that railway passenger numbers had been growing significantly in recent years, doubling from 1995 to 2015[171] and that the Rugby – Euston section was expected to have insufficient capacity some time around 2025.[172] This is despite the major WCML upgrade, which was completed in 2008, lengthened trains and an assumption that plans to upgrade the route with cab signalling would be realised.[173]

According to the DfT, the primary purpose of HS2 is to provide additional capacity on the rail network from London to the Midlands and North.[174] It says the new line "would improve rail services from London to cities in the North of England and Scotland,[175] and that the chosen route to the west of London will improve passenger transport links to Heathrow Airport".[176] Additionally, if the new line were connected to the Great Western Main Line (GWML) and Crossrail, it would provide links with East and West London, and the Thames Valley.[177]

In launching the project, the DfT announced that HS2 between London and the West Midlands would follow a different alignment from the WCML, rejecting the option of further upgrading or building new tracks alongside the WCML as being too costly and disruptive, and because the Victorian-era WCML alignment was not suitable for very high speeds.[178]

In October 2016, Andrew Jones, a transport minister, suggested renaming HS2 as the 'Grand Union Railway', not to be confused with the Grand Junction Railway (today the West Coast Main Line). His reasoning for this was because HS2 is not about speed and is more about connectivity.[129] There is currently no firm proposal for this name and HS2 remains to be called HS2 or High Speed 2.

The Government expects that over the next 30 years, HS2 will cost £32 billion to build, provide £43.7 billion of economic benefits and generate £27 billion in fares.[179]

Support and opposition

HS2 has encountered significant support and opposition from various groups and organisations.

It is officially supported by the Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat parties as well as the Scottish National Party, and opposed by the UK Independence Party and Green Party. Some Conservative including Liam Fox, Labour and Liberal Democrat politicians do not support their party line, and oppose the HS2 scheme in detail; some support proposals for alternative routes; and some reject the whole principle of high-speed rail. The mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, called for a rethink over the HS2 terminus at Euston preferring Old Oak Common as the London terminus.[180][181]The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government formed in May 2010 stated in its initial programme for government its commitment to creating a high-speed rail network.[182]

Community engagement

HS2 Ltd announced in March 2012 that it will conduct consultations with local people and organisations along the London to West Midlands route through community forums, planning forums and an environment forum. Between them the forums will discuss the development of the route, the identification of potential impacts and look at the best approaches to mitigate these.[183] HS2 has also confirmed that the consultations will be conducted in line with the terms of the Aarhus Convention which commits organisations to provide access to environmental information they hold, and enable participation and challenge as part of decision making processes.[184]

Community forums

HS2 Ltd set up 25 community forums along Phase 1 in March 2012. The forums provide for representatives of local authorities, residents associations, special interest groups and environment bodies in each community forum area to 'engage' with HS2 Ltd to:- "discuss potential ways to avoid and mitigate the environmental impacts of the route, such as screening views of the railway; managing noise and reinstating highways; highlight local priorities for the route design; identify possible community benefits."[185] Forum meetings will take place every 2–3 months and will have an independent chairman appointed by HS2.

Planning forums

Six planning forums aligned to local council boundaries along Phase 1 of the route were announced by HS2 in April 2012. Membership would comprise HS2 Ltd and officers from highway and planning authorities. Meeting every two months, their particular focus would include, location specific constraints, design and impacts, including construction; spatial planning considerations; the planning regime to be set out in the hybrid bill; and proposals for mitigations.[186]

Environment forum

An environment forum involving HS2 Ltd and national representatives of environmental organisations and government departments has been formed to assist with the development of the HS2 environmental policy.[187]

Environmental and community impact

Visual impact

The visual impact of HS2 has received particular attention in the Chilterns, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[189] The Government announced in January 2011 that two million trees would be planted along sections of the route to mitigate the visual impact.[190]

Property demolition, land take and compensation

Phase 1 will result in the demolition of more than 400 houses; 250 around Euston station, 20–30 between Old Oak Common and West Ruislip, a number in Ealing, around 50 in Birmingham, and the remainder in pockets along the route.[191] No Grade I or Grade II* listed buildings will be demolished, but six Grade II listed buildings will be, with alterations to four and removal and relocation of eight.[192] In Birmingham, the new Curzon Gate student residence will be demolished[193] and Birmingham City University wanted a £30 million refund after the plans were revealed.[87]

From the beginning of the HS2 consultation period, the government has factored in several plans to compensate people who will or may be affected. Once original plans had been released in 2010, the Exceptional Hardship Scheme (EHS) was set up, however this was at the government's discretion and Phase 1 came to an end on 17 June 2010. With EHS Phase 2 running throughout 2013. Both EHS are intended to compensate homeowners who have difficulty selling their home because of the HS2 route announcement, to protecting those whose property value may be seriously affected by the 'preferred route option' and who urgently need to sell.[194]

Ancient woodland impact

The Woodland Trust claims that 98 ancient woodlands will suffer loss or be damaged due to HS2, and 34 more will be affected by disturbance, noise and pollution.[195] In England, ancient woods are areas that have been continuously wooded since 1600 and are the country's richest land-based habitat, with a complex and diverse ecology of plants and animals.[196] According to the Trust, 40 hectares (0.4 km2) are threatened with total loss from the construction of phases 1 and 2a,[197] which is 0.01% of England's 340,000 hectares (3,400 km2) of ancient woodlands.[196] To mitigate the loss, HS2 Ltd says that during phase 1 it will plant 7 million trees and shrubs, creating 900 hectares (9 km2) of new woods.[198]

Loss of wildlife habitat, and recreation space

David Lidington, MP for Aylesbury, raised concerns that the route could damage the 47 kilometres (29 mi)-wide Chiltern Hills area of outstanding natural beauty, the Colne Valley regional park on the outskirts of London, and other areas of green belt.[199]

The route passes through the Chilterns in Buckinghamshire via the Misbourne Valley. Initially through a tunnel beneath Chalfont St Giles[200] emerging just after Amersham, then past Wendover and Stoke Mandeville.[201] Its proposals include a re-alignment of more than 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) of the River Tame, and construction of a 0.63 km (0.39 mi) viaduct and a cutting[202] through ancient woodland at a nature reserve at Park Hall on the edge of Birmingham.[203]

Carbon emissions

In 2007 the DfT commissioned a report, Estimated Carbon Impact of a New North South Line, from Booz Allen Hamilton to investigate the likely overall carbon impact associated with the construction and operation of a new rail line to either Manchester or Scotland including the extent of carbon reduction or increase from population shift to rail use, and the comparison with the case in which no new high-speed lines were built.[204] The report concluded that there was no net carbon benefit in the foreseeable future taking only the route to Manchester. Additional carbon from building a new rail route would be larger in the first ten years at least than a model were no new rail line was built.[205]

The High Speed Rail Command paper published in March 2010 stated that the project was likely to be roughly carbon neutral.[206]

The Eddington Report cautioned against the common argument of modal shift from aviation to high-speed rail as a carbon-emissions benefit, since only 1.2% of UK carbon emissions are due to domestic commercial aviation, and since rail transport energy efficiency is reduced as speed increases.[207]

The 2007 Government White Paper Delivering a Sustainable Railway stated trains that travel at a speed of 350 kilometres per hour (220 mph) used 90% more energy than at 200 kilometres per hour (125 mph);[208] which would result in carbon emissions for a London to Edinburgh journey of approximately 14 kilograms (31 lb) per passenger for high-speed rail compared to 7 kilograms (15 lb) per passenger for conventional classic rail. Air travel uses 26 kilograms (57 lb) per passenger for the same journey. The paper questioned the value for money of high-speed rail as a method of reducing carbon emissions, but noted that with a switch to carbon-free or neutral energy production the case becomes much more favourable.[208]

The House of Commons Transport Select Committee Report in November 2011 (paragraph 77) concluded that the Government's claim that HS2 would have substantial carbon reduction benefits did not stand up to scrutiny. At best, the Select Committee found, HS2 could make a small contribution to the Government's carbon-reduction targets. However this was dependent on the government making rapid progress on reducing carbon emissions from UK electricity generation.[17]

Noise

HS2 Ltd stated that 21,300 dwellings could experience a noticeable increase in rail noise and 200 non-residential receptors (community, education, healthcare, and recreational/social facilities) within 300 metres (980 ft) of the preferred route have the potential to experience significant noise impacts.[191] The Government has announced that trees planted to create a visual barrier will reduce noise pollution.[190]

Exceptional Hardship Scheme criteria

With Phase 1 applications intended to run from about August 2010 until the route was chosen in 2012 and Phase 2 throughout 2013; homeowners are/were advised to apply to the Secretary of State to buy their home, as long as all of the following criteria are met:

- Residential owner-occupier.

- Pressing need to sell. This means a change in employment location, extreme financial pressure, to accommodate enlarged family, move into sheltered accommodation, or medical condition of a family member.

- On or in 'close vicinity' of the 'preferred route' (that is mainly those who will later on be covered by statutory blight provisions).

- Have tried to sell – been on the market for at least three months with no offers within 15% of full market value (as if no HS2).

- Can demonstrate inability to sell is due to HS2.

- No knowledge of HS2 before acquiring the property.

Decisions on individual applications will be made by a panel of experts.[209]

Public consultations

Since the announcement of Phase 1 the government has had plans to create an overall 'Y shaped' line with termini in Manchester and Leeds. Since the intentions to further extend were announced an additional compensation scheme was set up.[210] Consultations with those affected were set up over late 2012 and January 2013, to allow homeowners to express their concerns within their local community.[211]

The results of the consultations are not yet known, but Alison Munro, chief executive of HS2 Ltd, has stated that it is also looking at other options, including property bonds.[212] The statutory blight regime would apply to any route confirmed for a new high-speed line following the public consultations, which took place between 2011 and January 2013.[213][211]

The government has said it plans to introduce a new discretionary hardship scheme to ensure the housing market along the route is not unduly disrupted.

HS2 Action Alliance's alternative compensation solution for property blight was presented to DfT/HS2 Ltd and Secretary of State for Transport Philip Hammond, in response to the consultation on the EHS. The Alliance also presented DfT and HS2 Ltd with a pilot study on property blight.[214]

Political impact

The revision of the route through South Yorkshire, which replaced the original plans for a station at Meadowhall for a station off the HS2 tracks at Sheffield was cited as a major reason for the collapse of the Sheffield City Region devolution deal; Sheffield City Council's successful lobbying for a city-centre station in opposition to Barnsley, Doncaster, and Rotherham's preference to the Meadowhall option caused Doncaster and Barnsley councils to seek an all-Yorkshire devolution deal instead.[215][216]

Construction

Construction commenced in 2018. In October 2018 the demolition of the former carriage sheds at Euston station. The work will allow the start of construction of the tunnels taking the route from Euston out of London.[217][218]

Civil engineering works for the actual line are scheduled to commence in June 2019, delayed from the original target date of November 2018. The civil aspect of the construction of Phase 1 is worth roughly £6.6 billion with preparation including over 8,000 boreholes for ground investigation.[219]

See also

Notes

- ↑ In British usage, a parkway station is one with car parking, which may be at a distance from the area it serves

- ↑ The British Rail Class 373 trains used by Eurostar are an example of a high-speed train that is compatible with French/Belgian high-speed lines and British lines.

References

- ↑ "High Speed 2 (HS2) Railway - Railway Technology".

- 1 2 DfT 2010, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 "High Speed Two From Concept to Reality July 2017" (PDF). GOV.UK. Department for Transport. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ↑ "HS2: Phase 1 of high-speed rail line gets go-ahead". BBC News. 10 January 2012.

- ↑ "Go-ahead given to new railway". Department for Transport. January 2012.

- ↑ "HS2 suffers setback as legislation delayed by 12 months". www.railtechnologymagazine.com.

- ↑ "HS2: North West and Yorkshire Routes Confirmed". BBC News. 15 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ HIGH SPEED TWO PHASE ONE INFORMATION PAPER F1: ROLLING STOCK DEPOT AND STABLING STRATEGY (PDF) (Report). HS2 Ltd. 23 February 2017. p. 3. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ↑ "CHAPTER 2: THE COST OF HS2".

- ↑ "Constructing the HS2 railway". GOV.UK. 23 August 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ↑ Britain’s Transport Infrastructure High Speed Two (PDF). DfT. January 2009. p. 5. ISBN 978 1 906581 80 0. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ↑ "Transport secretary unveils HS2 compensation plan". Railnews. Stevenage. 29 November 2010.

- 1 2 "London-to-Birmingham high speed train route announced". BBC News. 20 December 2010.

- ↑ "'Redrawn' high speed rail plan unveiled". Channel 4 News. 20 December 2010.

- ↑ "High Speed Rail – Oral Answers to Questions – Education – House of Commons debates". 20 December 2010. question to the Minister by Maria Eagle, shadow secretary for Transport, 1st para.

- 1 2 "Britain to have new national high-speed rail network".

- 1 2 Transport Select Committee HS2 Report – House of Commons, November 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2012

- ↑ "HS2 Hybrid Bill receives Royal Assent".

- ↑ "Oral statement to Parliament, HS2 update: Phase 2a and Phase 2b". GOV.UK. 18 July 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ↑ "HS2 Phase 2a: economic case – Publications". GOV.UK. 30 November 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "HS2: North West and Yorkshire routes confirmed". 15 November 2016 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "High Speed Two: From Crewe to Manchester, the West Midlands to Leeds and beyond" (PDF).

- 1 2 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/568268/high-speed-two-crewe-manchester-west-midlands-leeds-print-version.pdf

- 1 2 3 Nick Giesler et al., for Environmental Resources Management (ERM). "HS2 Phase Two Initial Preferred Scheme : Sustainability Summary, section 4.2.13" (PDF). High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. p. 21.

- ↑ "Government pledge on Sheffield rail line amid HS2 'funding gap' fear".

- 1 2 "Counting the real cost of HS2 Meadowhall station plan". The Star. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Violent outbursts at Doncaster HS2 meeting". BBC News. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "HS2 South Yorkshire route change threatens new estate". BBC News. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "Council claim victory over Sheffield HS2 station move". BBC News. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "Chesterfield - High Speed 2".

- ↑ "HS2 phase two initial preferred route plan and profile maps". Transport planning and infrastructure. Department for Transport. January 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Proposed high speed rail network North of Birmingham confirmed" (Press release). Department for Transport. 4 October 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- 1 2 "The Yorkshire Hub" (PDF). Department for Transport. p. 10. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ "Transport Secretary will consider a possibility of a 'South Yorkshire Hub'". 4 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ "South Yorkshire Route Document" (PDF). July 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ "Head of HS2 backs South Yorkshire Parkway – Proposed Railway Schemes". Proposed Railway Schemes. 16 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "HS2: Eight 'parkway' station proposal sites revealed". 25 January 2017 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "MPs to press for M18 station to serve HS2 line". www.yorkshirepost.co.uk.

- ↑ "Leaders campaign for HS2 'parkway' station in South Yorkshire".

- ↑ "HS2 boss: South Yorkshire politicians must decide 'M18 route' parkway station location".

- ↑ "High Speed 2 (HS2) Phases 2a, 2b and beyond" (PDF).

- ↑ "Government confirms provision to join HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail for Liverpool City Region – Liverpool BID Company". www.liverpoolbidcompany.com.

- ↑ Topham, Gwym (23 February 2016). "Liverpool offers £2bn to be included in HS2 network". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- 1 2 Fast Track Scotland: Making the Case for High Speed Rail Connections with Scotland (PDF). Scottish Partnership Group for High Speed Rail. December 2011. p. 10. ISBN 9781908181213.

- ↑ "HS2 will be the 'Union Railway' of England and Scotland – Adonis". Railnews. 29 September 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "High-speed rail plan for Glasgow to Edinburgh line". BBC News. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "High speed Glasgow-Edinburgh rail link plans 'shelved'". BBC News. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ↑ Leftly, Mark (24 May 2015). "SNP fury as HS2 finds 'no business case' for taking fast train service to Scotland". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "The key policy choices for Anglo-Scottish HSR" (PDF). Greengauge 21. September 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "Warnings Glasgow City Centre will need a third major station in less than twenty years". Evening Times. Glasgow. 14 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Calls to scrap plans for HS2 station that would bypass York". York Press.

- 1 2 3 "High speed rail: investing in Britain 's future phase two – the route to Leeds, Manchester and beyond summary" (PDF). DfT. 23 January 2013. pp. 5, 16–17. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ DfT 2009, p. 16 para. 37.

- ↑ Savage, Michael (2 February 2010). "Adonis in all-party talks on high-speed rail link". The Independent. London. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ "Conclusions and recommendations – conclusions and the way ahead". UK Parliament. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ↑ "3. HS1-HS2 Link" (PDF). HS2 London – West Midlands Design Refinement Consultation. Department for Transport. May 2013. p. 21. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ DfT 2010, p. 9.

- ↑ "High Speed Rail: Oral statement by: The Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP". Department for Transport. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010.

- ↑ "New High Speed Rail Proposals Unveiled" (Press release). Department for Transport. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010.

- ↑ Arup (20 December 2010). "Review of HS1 to HS2 Connection Final Report" (PDF). Department for Transport. Section 2.1 "Structural modifications" , p.4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2011.

- ↑ "Plan of the route connecting HS2 to HS1 showing which map covers which area – drawing number HS2-ARP-00-DR-RW-05140" (PDF). Arup/DfT. 5 January 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "HS2's cost to Camden". London Borough of Camden. July 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "HS2 plans 'threaten jobs' in Camden's markets". BBC News. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "London mayor Boris Johnson calls for tunnel to link HS2 at Euston to St Pancras". Evening Standard. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "High Speed Rail (London – West Midlands) Bill". Hansard. UK Parliament. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/507791/High_Speed_North.pdf

- ↑ "Budget 2016: HS3 and wider M62 announced". BBC News. 16 March 2016.

- ↑ "IPPR urges government to prioritise HS3 link – BBC News". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "Progress of High Speed Two examined".

- ↑ Tute, Ryan (7 March 2018). "Firm pitches "an M25 for high-speed trains" to pass through Heathrow and Gatwick". Infrastructure Intelligence. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- 1 2 High Speed Rail: Investing in Britain's Future Consultation Archived 12 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine., Department for Transport February 2011

- ↑ Subject: Proposal for Examining the Potential Effect of High Speed 2 on London's Transport Network, Greater London Authority 17 May 2011

- ↑ High Speed 2 automated people mover (APM) Euston Station to St Pancras International further investigation final report Department for Transport Archives

- ↑ Transport Select Committee, 28 June 2011, House of Commons

- ↑ "HS2 fuels Crossrail 2 business case". Transportxtra.com. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 Harris, Nigel (28 July 2010). "'No business case' to divert HS2 via Heathrow, says Mawhinney'". Rail (649). Peterborough. pp. 6–7.

- ↑ DfT 2010, p. 107.

- ↑ DfT (2012 Maps).

- ↑ DfT 2010, p. 118.

- ↑ "High Speed Two Phase One Information Paper H2: Birmingham Interchange Station" (PDF). gov.uk. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. 23 February 2017. pp. 3, 10. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Nielsen, Beverley (29 October 2010). "Up, Up and Away – Birmingham Airport spreads its wings as powerful driver of growth and jobs". Birmingham Post Business Blog.

- ↑ DfT 2010, p. 112.

- ↑ "3". High Speed Rail: London to the West Midlands and Beyond. A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited (PDF). p. 117. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "The first half of the new concourse at Birmingham New Street station will open on 28 April 2013". Network Rail. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ "High Speed Two Information Paper H4: Birmingham Curzon Street Station" (PDF). gov.uk. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. pp. 4.1 and 6.3. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Network Rail. Transforming Birmingham New Street. Archived from the original on 28 August 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- 1 2 Walker, Jonathan (16 March 2010). "Birmingham City University wants £30m refund after high speed rail hits campus plan". Birmingham Post. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ↑ DfT 2010, p. 115.

- ↑ Ikon Gallery. Curzon Square – A vision for Birminghams New Museum Quarter (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- 1 2 Millward, David (6 January 2013). "HS2 route: Manchester and Liverpool win while Sheffield loses out". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ↑ "Stoke-on-Trent 'ignored' under HS2 rail route plans". BBC News. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Route section HSM09 plan and profile sheet 2 of 2 – drawing number HS2-MSG-WCM-ZZ-DT-RT-60902" (PDF). HS2 phase two initial preferred route plan and profile maps. Department for Transport. January 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "UPDATE: HS2 in Crewe by 2027 – chairman backs Crewe hub station plan (From Crewe Guardian)". Creweguardian.co.uk. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ "HS2 Birmingham to Crewe link planned to open six years early". BBC News. 30 November 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.