Shinkansen

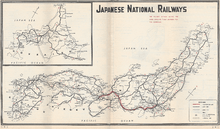

The Shinkansen (Japanese: 新幹線, pronounced [ɕĩŋkã̠ɰ̃sẽ̞ɴ]), colloquially known in English as the bullet train, is a network of high-speed railway lines in Japan. Initially built to connect distant Japanese regions with Tokyo, the capital, in order to aid economic growth and development, beyond long-distance travel some sections around the largest metropolitan areas are used as a commuter rail network.[1][2] It is operated by five Japan Railways Group companies.

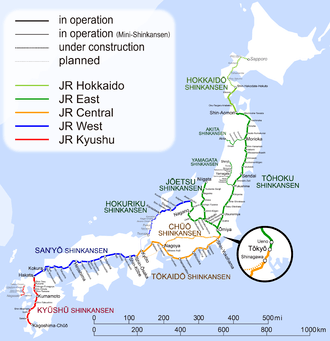

Starting with the Tōkaidō Shinkansen (515.4 km, 320.3 mi) in 1964,[3] the network has expanded to currently consist of 2,764.6 km (1,717.8 mi) of lines with maximum speeds of 240–320 km/h (150–200 mph), 283.5 km (176.2 mi) of Mini-Shinkansen lines with a maximum speed of 130 km/h (80 mph), and 10.3 km (6.4 mi) of spur lines with Shinkansen services.[4] The network presently links most major cities on the islands of Honshu and Kyushu, and Hakodate on northern island of Hokkaido, with an extension to Sapporo under construction and scheduled to commence in March 2031.[5] The maximum operating speed is 320 km/h (200 mph) (on a 387.5 km section of the Tōhoku Shinkansen).[6] Test runs have reached 443 km/h (275 mph) for conventional rail in 1996, and up to a world record 603 km/h (375 mph) for SCMaglev trains in April 2015.[7]

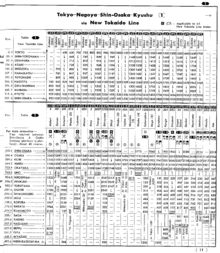

The original Tōkaidō Shinkansen, connecting Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka, Japan’s three largest cities, is the world's busiest high-speed rail line. In the one-year period preceding March 2017, it carried 159 million passengers[8], and since its opening more than five decades ago, it has transported more than 5.6 billion total passengers[9][10] The service on the line operates much larger trains and at higher frequency than most other high speed lines in the world. At peak times, the line carries up to thirteen trains per hour in each direction with sixteen cars each (1,323-seat capacity and occasionally additional standing passengers) with a minimum headway of three minutes between trains.

Japan's Shinkansen network had the highest annual passenger ridership (a maximum of 353 million in 2007) of any high-speed rail network until 2011, when the Chinese high-speed railway network surpassed it at 370 million passengers annually, reaching over 1.7 billion annual passengers in 2017,[11] though the total cumulative passengers, at over 10 billion, is still larger.[12] While the Shinkansen network has been expanding, Japan's declining population is expected to cause ridership to decline over time. The recent expansion in tourism has boosted ridership marginally.

Etymology

Shinkansen (Japanese: 新幹線) in Japanese means new trunkline or new main line, but the word is used to describe both the railway lines the trains run on and the trains themselves.[13] In English, the trains are also known as the bullet train. The term bullet train (Japanese: 弾丸列車 Hepburn: dangan ressha) originates from 1939, and was the initial name given to the Shinkansen project in its earliest planning stages.[14] Furthermore, the name superexpress (Japanese: 超特急 Hepburn: chō-tokkyū), used exclusively until 1972 for Hikari trains on the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, is used today in English-language announcements and signage.

History

Japan was the first country to build dedicated railway lines for high-speed travel. Because of the mountainous terrain, the existing network consisted of 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) narrow-gauge lines, which generally took indirect routes and could not be adapted to higher speeds. Consequently, Japan had a greater need for new high-speed lines than countries where the existing standard gauge or broad gauge rail system had more upgrade potential.

Among the key people credited with the construction of the first Shinkansen are Hideo Shima, the Chief Engineer, and Shinji Sogō, the first President of Japanese National Railways (JNR) who managed to persuade politicians to back the plan. Other significant people responsible for its technical development were Tadanao Miki, Tadashi Matsudaira, and Hajime Kawanabe based at the Railway Technology Research Institute (RTRI), part of JNR. They were responsible for much of the technical development of the first line, the Tōkaidō Shinkansen. All three had worked on aircraft design during World War II.[15]

Early proposals

The popular English name bullet train is a literal translation of the Japanese term dangan ressha (弾丸列車), a nickname given to the project while it was initially being discussed in the 1930s. The name stuck because of the original 0 Series Shinkansen's resemblance to a bullet and its high speed.

The Shinkansen name was first formally used in 1940 for a proposed standard gauge passenger and freight line between Tokyo and Shimonoseki that would have used steam and electric locomotives with a top speed of 200 km/h (120 mph). Over the next three years, the Ministry of Railways drew up more ambitious plans to extend the line to Beijing (through a tunnel to Korea) and even Singapore, and build connections to the Trans-Siberian Railway and other trunk lines in Asia. These plans were abandoned in 1943 as Japan's position in World War II worsened. However, some construction did commence on the line; several tunnels on the present-day Shinkansen date to the war-era project.

Construction

Following the end of World War II, high-speed rail was forgotten for several years while traffic of passengers and freight steadily increased on the conventional Tōkaidō Main Line along with the reconstruction of Japanese industry and economy. By the mid-1950s the Tōkaidō Line was operating at full capacity, and the Ministry of Railways decided to revisit the Shinkansen project. In 1957, Odakyu Electric Railway introduced its 3000 series SE Romancecar train, setting a world speed record of 145 km/h (90 mph) for a narrow gauge train. This train gave designers the confidence that they could safely build an even faster standard gauge train. Thus the first Shinkansen, the 0 series, was built on the success of the Romancecar.

In the 1950s, the Japanese national attitude was that railways would soon be outdated and replaced by air travel and highways as in America and many countries in Europe. However, Shinji Sogō, President of Japanese National Railways, insisted strongly on the possibility of high-speed rail, and the Shinkansen project was implemented.

Government approval came in December 1958, and construction of the first segment of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka started in April 1959. The cost of constructing the Shinkansen was at first estimated at nearly 200 billion yen, which was raised in the form of a government loan, railway bonds and a low-interest loan of US$80 million from the World Bank. Initial cost estimates, however, had been deliberately understated and the actual figures were nearly double at about 400 billion yen. As the budget shortfall became clear in 1963, Sogo resigned to take responsibility.[16]

A test facility for rolling stock, now part of the line, opened in Odawara in 1962.

Initial success

The Tōkaidō Shinkansen began service on 1 October 1964, in time for the first Tokyo Olympics.[17] The conventional Limited Express service took six hours and 40 minutes from Tokyo to Osaka, but the Shinkansen made the trip in just four hours, shortened to three hours and ten minutes by 1965. It enabled day trips between Tokyo and Osaka, the two largest metropolises in Japan, changed the style of business and life of the Japanese people significantly, and increased new traffic demand. The service was an immediate success, reaching the 100 million passenger mark in less than three years on 13 July 1967, and one billion passengers in 1976. Sixteen-car trains were introduced for Expo '70 in Osaka. With an average of 23,000 passengers per hour in each direction in 1992, the Tōkaidō Shinkansen was the world's busiest high-speed rail line.[18] As of 2014, the train's 50th anniversary, daily passenger traffic had risen to 391,000 which, spread out over its 18-hour schedule, represented an average of just under 22,000 passengers an hour.[19]

The first Shinkansen trains, the 0 series, ran at speeds of up to 210 km/h (130 mph), later increased to 220 km/h (137 mph). The last of these trains, with their classic bullet-nosed appearance, were retired on 30 November 2008. A driving car from one of the 0 series trains was donated by JR West to the National Railway Museum in York, England in 2001.[20]

Network expansion

The Tōkaidō Shinkansen's rapid success prompted an extension westward to Okayama, Hiroshima and Fukuoka (the Sanyō Shinkansen), which was completed in 1975. Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka was an ardent supporter of the Shinkansen, and his government proposed an extensive network paralleling most existing trunk lines. Two new lines, the Tōhoku Shinkansen and Jōetsu Shinkansen, were built following this plan. Many other planned lines were delayed or scrapped entirely as JNR slid into debt throughout the late 1970s, largely because of the high cost of building the Shinkansen network. By the early 1980s, the company was practically insolvent, leading to its privatization in 1987.

Development of the Shinkansen by the privatised regional JR companies has continued, with new train models developed, each generally with its own distinctive appearance (such as the 500 series introduced by JR West). Since 2014, shinkansen trains run regularly at speeds up to 320 km/h (200 mph), placing them alongside the French TGV and German ICE as the fastest trains in the world.

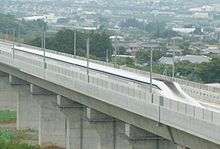

Since 1970, development has also been underway for the Chūō Shinkansen, a planned maglev line from Tokyo to Osaka. On 21 April 2015, a seven-car L0 series maglev trainset set a world speed record of 603 km/h (375 mph).[7]

Technology

To enable high-speed operation Shinkansen uses a range of advanced technology compared with conventional rail, achieving not only high speed but also a high standard of safety and comfort. Its success has influenced other railways in the world and the importance and advantage of high-speed rail has consequently been reevaluated.

Routing

Shinkansen routes are completely separate from conventional rail lines (except Mini-shinkansen which goes through to conventional lines). Consequently, the shinkansen is not affected by slower local or freight trains (except for Hokkaido Shinkansen while traveling through the Seikan Tunnel), and has the capacity to operate many high-speed trains punctually. The lines have been built without road crossings at grade. Tracks are strictly off-limits with penalties against trespassing strictly regulated by law. It uses tunnels and viaducts to go through and over obstacles rather than around them, with a minimum curve radius of 4,000 meters (2,500 meters on the oldest Tōkaidō Shinkansen).[21]

Track

The Shinkansen uses 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge in contrast to the 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) narrow gauge of older lines. Continuous welded rail and swingnose crossing points are employed, eliminating gaps at turnouts and crossings. Long rails are used, joined by expansion joints to minimize gauge fluctuation due to thermal elongation and shrinkage.

A combination of ballasted and slab track is used, with slab track exclusively employed on concrete bed sections such as viaducts and tunnels. Slab track is significantly more cost-effective in tunnel sections, since the lower track height reduces the cross-sectional area of the tunnel, thereby reducing construction costs by up to 30%.[22] However, the smaller diameter of Shinkansen tunnels compared to some other high-speed lines has resulted in the issue of tunnel boom becoming a concern for residents living close to tunnel portals.

The slab track consists of rails, fasteners and track slabs with a cement asphalt mortar. On the roadbed and in tunnels, circular upstands (measuring 400–520 mm in diameter and 200 mm high) are located at 5 metre intervals. The prefabricated upstands are made of either reinforced concrete or pre-stressed reinforced concrete; they prevent the track slab from moving along either the latitudinal or the longitudinal directions. One track slab weighs approximately 5 tons, measuring 2220–2340 mm wide, 4900–4950 mm long and 160–200 mm thick.[23]

Signal system

The Shinkansen employs an ATC (Automatic Train Control) system, eliminating the need for trackside signals. It uses a comprehensive system of Automatic Train Protection.[16] Centralized traffic control manages all train operations, and all tasks relating to train movement, track, station and schedule are networked and computerized.

Electrical systems

Shinkansen uses a 25kV AC overhead power supply (20 kV AC on Mini-shinkansen lines), to overcome the limitations of the 1,500 V direct current used on the existing electrified narrow-gauge system. Power is distributed along the axles of the train to reduce the heavy axle loads under single power cars.[16] The AC frequency of the power supply for the Tokaido Shinkansen is 60 Hz.

Trains

Shinkansen trains are electric multiple units, offering fast acceleration, deceleration and reduced damage to the track because of the use of lighter vehicles compared to locomotives or power cars. The coaches are air-sealed to ensure stable air pressure when entering tunnels at high speed.

Punctuality

The Shinkansen is very reliable thanks to several factors, including its near-total separation from slower traffic. In 2016, JR Central reported that the Shinkansen's average delay from schedule per train was 24 seconds. This includes delays due to uncontrollable causes, such as natural disasters.[24] The record, in 1997, was 18 seconds.

Traction

The Shinkansen has used the electric multiple unit configuration from the outset, with the 0 Series Shinkansen having all axles powered. Other railway manufacturers were traditionally reluctant, or unable to use distributed traction configurations (e.g. Talgo used the locomotive configuration with the AVE Class 102 and continues with it for the Talgo AVRIL on account of the fact that it is not possible to use powered bogies as part of the Talgo Pendular system). In Japan, significant engineering desirability exists for the electric multiple unit configuration. A greater proportion of motored axles results in higher acceleration, meaning that the Shinkansen does not lose as much time if stopping frequently. Shinkansen lines have more stops in proportion to their lengths than high-speed lines elsewhere in the world.

Safety record

Over the Shinkansen's 50-plus year history, carrying over 10 billion passengers, there have been no passenger fatalities due to derailments or collisions,[25] despite frequent earthquakes and typhoons. Injuries and a single fatality have been caused by doors closing on passengers or their belongings; attendants are employed at platforms to prevent such accidents.[26] There have, however, been suicides by passengers jumping both from and in front of moving trains.[27] On 30 June 2015, a passenger committed suicide on board a Shinkansen train by setting himself on fire, killing another passenger and seriously injuring seven other people.[28]

There have been two derailments of Shinkansen trains in passenger service. The first one occurred during the Chūetsu earthquake on 23 October 2004. Eight of ten cars of the Toki No. 325 train on the Jōetsu Shinkansen derailed near Nagaoka Station in Nagaoka, Niigata. There were no casualties among the 154 passengers.[29]

Another derailment happened on 2 March 2013 on the Akita Shinkansen when the Komachi No. 25 train derailed in blizzard conditions in Daisen, Akita. No passengers were injured.[30]

In the event of an earthquake, an earthquake detection system can bring the train to a stop very quickly, newer trainsets are lighter and have stronger braking systems, allowing for quicker stopping. A new anti-derailment device was installed after detailed analysis of the Jōetsu derailment.

Several months after the expose of the Kobe Steel falsification scandal, which is among the suppliers of high-strength steel for shinkansen trainsets, cracks were found upon inspection of a single bogie, and removed from service on 11 December 2017.[31]

Economics

The Shinkansen has had a significant beneficial effect on Japan's business, economy, society, environment and culture in ways beyond mere construction and operation contributions.[18] The results in time savings alone from switching from a conventional to a high-speed network have been estimated at 400 million hours, and the system has an economic impact of ¥500 billion per year.[18] That does not include the savings from reduced reliance on imported fuel, which also has national security benefits. Shinkansen lines, particularly in the very crowded coastal Taiheiyō Belt megalopolis, met two primary goals:

- Shinkansen trains reduced the congestion burden on regional transportation by increasing throughput on a minimal land footprint, therefore being economically preferable compared to modes (such as airports or highways) common in less densely populated regions of the world.

- As rail was already the primary urban mode of passenger travel, from that perspective it was akin to a sunk cost; there was not a significant number of motorists to convince to switch modes. The initial megalopolitan Shinkansen lines were profitable and paid for themselves. Connectivity rejuvenated rural towns such as Kakegawa that would otherwise be too distant from major cities.[18]

However, the initial Shinkansen prudence gave way to political considerations to extend the mode to far less populated regions of the country, partly to spread these benefits beyond the key centres of Kanto and Kinki. In some areas regional extension was frustrated by protracted land acquisition issues, sometimes influenced by fierce protests from locals against expanding Narita airport's runways to handle more traffic that extended well into the 2000s. Tokyo's airports were already at or near capacity and there was no room for another civilian airport given the geography and required US military presence. Shinkansen lines were extended to sparsely populated areas with the intent the network would disperse the population away from the capital.

Such expansion had a significant cost. JNR, the national railway company, was already burdened with subsidizing unprofitable rural and regional railways. Additionally it assumed Shinkansen construction debt to the point the government corporation eventually owed some ¥28 trillion, contributing to it being regionalised and privatized.[32] The privatized JRs eventually paid a total of ¥9.2 trillion to acquire JNR's Shinkansen network.[18]

After privatization, the Shinkansen network continues to see significant expansion to less populated areas, but with far more flexibility to spin off unprofitable railways or cut costs than in JNR days. Currently an important factor is the post bubble zero interest-rate policy that allows JR to borrow huge sums of capital without significant concern regarding repayment timing.

Environmental impact

Traveling by the Tokaido Shinkansen from Tokyo to Osaka produces only around 16% of the carbon dioxide of the equivalent journey by car, a saving of 15,000 tons of CO2 per year.[18]

Challenges encountered

Noise pollution

Noise pollution concerns mean that increasing speed is becoming more difficult. In Japan, the population density is high and there have been severe protests against the Shinkansen's noise pollution, meaning that its noise is now limited to less than 70 dB in residential areas.[33] Hence, improvement and reduction of the pantograph, weight saving of cars, and construction of noise barriers and other measures have been implemented. Current research is primarily aimed at reducing operational noise, particularly the tunnel boom phenomenon caused when trains transit tunnels at high speed.

Earthquake

Because of the risk of earthquakes, the Urgent Earthquake Detection and Alarm System (UrEDAS) (earthquake warning system) was introduced in 1992. It enables automatic braking of bullet trains in the case of large earthquakes.

Heavy snow

The Tōkaidō Shinkansen often experiences heavy snow in the area around Maibara Station in winter. Trains have to reduce speed, which can disrupt the timetable. Sprinkler systems were later installed, but delays of 10 to 20 minutes still occur during snowy weather. Additionally, treefalls related to excess snow have caused service interruptions. Along the route of the Jōetsu Shinkansen, winter snow can be very heavy, with snow depths of two to three metres, so the line is equipped with stronger sprinklers and slab track, to mitigate the effects of deep snow.

Ridership

Annual

| Tokaido | Tohoku | Sanyo | Joetsu | Nagano | Kyushu | Hokkaido | Sum* | Total (excl. transfers) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY2007 | 151.32 | 84.83 | 64.43 | 38.29 | 10.13 | 4.18 | - | 353.18 | 315.77 |

| FY2015 | 162.97 | 90.45 | 72.06 | 42.96 | 31.84 | 13.65 | **0.10 | 414.03 | 365.71 |

| FY2016 | 167.72 | 91.09 | 72.53 | 43.06 | 30.75 | 13.27 | 2.11 | 420.53 |

* The sum of the ridership of individual lines does not equal the ridership of the system because a single rider may be counted multiple times when using multiple lines, to get proper ridership figures for a system, in the above case, is only counted once.

** Only refers to 6 days of operation: 26 March 2016 (opening date) to 31 March 2016 (end of FY2015).

Until 2011, Japan's high-speed rail system had the highest annual patronage of any system worldwide, China's HSR network's patronage reached 440 million and is now the highest.[9]

Cumulative comparison

| Year | Shinkansen (see notes) | Asia (other) | Europe | World | Shinkansen share (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | 11.0 | 0 | 0 | 11.0 | 100% |

| 1980 | 1,616.3 | 0 | 0 | 1,616.3 | 100% |

| 1985 | 2,390.3 | 0 | 45.7 | 2,436.0 | 98.1% |

| 1990 | 3,559.1 | 0 | 129.9 | 3,689.0 | 96.5% |

| 1995 | 5,018.0 | 0 | 461 | 5,479 | 91.6% |

| 2000 | 6,531.7 | 0 | 1,103.5 | 7,635.1 | 85.5% |

| 2005 | 8,088.3 | 52.2 | 2,014.6 | 10,155.1 | 79.6% |

| 2010 | 9,651.0 | 965 | 3,177.0 | 15,417 | 70.8% |

| 2012 | 10,344 | 2,230 | 3,715 | 16,210 | 64.5% |

| 2014 | 11,050 | 3,910 | 4,300 | 19,260 | 57.4% |

Notes:

- Data in italics includes extrapolated estimations where data is missing. Turkey and Russia data here is included in "Europe" column, rather than split between Asia and Europe. Only systems with 200 km/h or higher regular service speed are considered.

- "Shinkansen share(%)" refers to percent of Shinkansen ridership (including fully assembled exported trainsets) as a percent of "World" total. Currently this only pertains to Taiwan, but may change if Japan exports Shinkansen to other nations.

- "Shinkansen" column does not include Shinkansen knock down kits made in Japan exported to China for assembly, or any derivative system thereof in China)

- "Asia (other)" column refers to sum of riderships of all HSR systems geographically in Asia that do not use Shinkansen. (this data excludes Russia and Turkey, which geographically have parts in Asia but for sake of convenience included in Europe column)

- For 2013, Japan's Ministry of Transport has not updated data, nor is summed European data available (even 2012 data is very rough), however Taiwan ridership is 47.49 million[37] and Korea with 54.5 million[38] and China with 672 million in 2013.[39]

Cumulative ridership since October 1964 is over 5 billion passengers for the Tokaido Shinkansen Line alone and 10 billion passengers for Japan's entire shinkansen network.[9]

Future

Speed increases

Tohoku Shinkansen

E5 series trains, capable of up to 320 km/h (200 mph) (initially limited to 300 km/h), were introduced on the Tōhoku Shinkansen in March 2011. Operation at the maximum speed of 320 km/h between Utsunomiya and Morioka on this route commenced on 16 March 2013, and reduced the journey time to around 3 hours for trains from Tokyo to Shin-Aomori (a distance of 674 km (419 mi)).

Extensive trials using the Fastech 360 test trains have shown that operation at 360 km/h (224 mph) is not currently feasible because of problems of noise pollution (particularly tunnel boom), overhead wire wear, and braking distances. On 30 October 2012, JR East announced that it is pursuing research and development to increase speeds to 360 km/h on the Tohoku Shinkansen by 2020.[40]

Hokkaido Shinkansen

As of 2016, the maximum speed on the approximately 82 km dual gauge section of the Hokkaido Shinkansen (including through the Seikan Tunnel) is 140 km/h (85 mph).[5] There are approximately 50 freight trains using the dual gauge section each day, so limiting the travel of such trains to times outside of Shinkansen services is not an option. Because of this and other weather-related factors cited by JR East and JR Hokkaido, the fastest journey time between Tokyo and Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto is currently 4 hours, 2 minutes.[41] The new section takes 61 minutes from Shin-Aomori to Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto on the fastest services.[41]

By 2018, it is proposed to allow one Shinkansen service each day to travel at 260 km/h (160 mph) (the maximum speed proposed for the tunnel) by ensuring no freight trains are scheduled to travel on the dual gauge section at that time. To achieve the full benefit of Shinkansen trains travelling on the dual gauge section at 260 km/h (160 mph), other alternatives are being considered, such as a system to automatically slow Shinkansen trains down to 200 km/h (125 mph) when passing narrow-gauge trains, and loading freight trains onto special "Train on Train" standard-gauge trains (akin to a covered piggyback flatcar train) built to withstand the shock wave of oncoming Shinkansen trains traveling at full speed. This would enable a travel time from Tokyo to Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto of 3 hours and 45 minutes, a saving of 17 minutes on the current timetable.

Hokuriku extension

The Hokuriku Shinkansen is being extended from Kanazawa to Tsuruga (proposed for completion by 2023) at an estimated cost of 3.04 trillion yen (in 2012 currency).[42]

There are further plans to extend the line from Tsuruga to Osaka, with the 'Obama-Kyoto' route chosen by the government on 20 December 2016,[43] after a government committee investigated the five nominated routes.[44] The five routes that were under investigation are detailed in the Hokuriku Shinkansen page.

Construction of the extension beyond Tsuruga is not expected to commence before 2030, with a projected 15 year construction period. On 6 March 2017 the government committee announced the chosen route from Kyoto to Shin-Osaka is to be via Kyotanabe, with a station at Matsuiyamate on the Katamachi Line.[45][46]

Interim plans

In order to extend the benefits of the Hokuriku Shinkansen to stations west of Tsuruga before the line to Osaka is completed, JR West is working in partnership with Talgo on the development of a Gauge Change Train (CGT), which will be capable of operating under both the 25 kV AC electrification used on the Shinkansen and the 1.5 kV DC system employed on conventional lines. The six-car train is due to start trials on the Hokuriku Shinkansen and the 1067 mm-gauge Hokuriku and Kosei lines in 2017. As part of the project JR West has already begun trials with a purpose-built 180-metre-long gauge-changer at Tsuruga.[47]

Tohoku extension/Hokkaido Shinkansen

The Hokkaido Shinkansen forms an extension of the Tohoku Shinkansen north of Shin-Aomori to Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto Station (north of the Hokkaido city of Hakodate) through the Seikan Tunnel, which was converted to dual gauge as part of the project, opening in March 2016.

JR Hokkaido is extending the Hokkaido Shinkansen from Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto to Sapporo to open by March 2031,[5] with tunnelling work on the 5,265 m Murayama tunnel, situated about 1 km north of Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto Station, commencing in March 2015, and due to be completed by March 2021. The 211.3 km extension will be approximately 76% in tunnels, including major tunnels such as Oshima (~26.5 km), Teine (~18.8 km) and Shiribeshi (~18 km).[48]

Although an extension from Sapporo to Asahikawa was included in the 1973 list of planned lines, at this time it is unknown whether the Hokkaido Shinkansen will be extended beyond Sapporo.

Nagasaki Shinkansen

JR Kyushu is constructing an extension (to be known as the West Kyushu Shinkansen) line of the Kyushu Shinkansen to Nagasaki, partly to full Shinkansen standard gauge construction standards (Takeo Onsen – Nagasaki) with the existing narrow gauge section between Shin-Tosu and Takeo Onsen to be upgraded as part of this project.

This proposal initially involved introducing Gauge Change Trains (GCT) travelling from Hakata to Shin-Tosu (26.3 km) on the existing Kyushu Shinkansen line, then passing through a specific gauge changing (standard to narrow) section of track linking to the existing Nagasaki Main Line, along which it would travel to Hizen Yamaguchi (37.6 km), then onto the Sasebo Line to Takeo Onsen (13.7 km), where another gauge changing section (narrow to standard) would lead onto the final Shinkansen line to Nagasaki (66.7 km). However, technical issues with the development of the GCT bogies means the train will not be available for service until at least 2025, requiring consideration of other options such as 'relay' service to ensure the line can open on schedule in 2023.[49]

The proposal shortens the distance between Hakata and Nagasaki by 6.2% (9.6 km), and while only 64% of the route will be built to full Shinkansen standards, it will eliminate the slowest sections of the existing narrow gauge route. Use of the GCT was estimated to result in a time saving of 28.5% (32 minutes) on the current timetable. The proposed time saving if a 'relay' service is introduced is unknown at this time.

As part of this proposal, the current 12.8 km section of single track between Hizen Yamaguchi and Takeo Onsen is to be duplicated, with work on that component scheduled to commence in April 2016.

With the completion of excavation of the 1351m Enogushi tunnel, being the sixth tunnel completed in this section, approximately 25% of the 40.7 km of tunnel excavation work on the Takeo Onsen – Nagasaki section has been finished. The entire project is scheduled for completion by March 2023.

Maglev (Chuo Shinkansen)

Maglev trains have been undertaking test runs on the Yamanashi test track since 1997, running at speeds of over 500 km/h (310 mph). As a result of this extensive testing, maglev technology is almost ready for public usage.[50] An extension of this test track from 18.4 km to 42.8 km was completed in June 2013, enabling extended high-speed running trials to commence in August 2013. This section will be incorporated into the Chūō Shinkansen which will eventually link Tokyo to Osaka. Construction of the Shinagawa to Nagoya section began in 2014, with 86% of the 286 km route to be in tunnels.

The CEO of JR Central announced plans to have the maglev Chūō Shinkansen operating from Tokyo to Nagoya by 2027.[50] Following the shortest route (through the Japanese Alps), JR Central estimates that it will take 40 minutes to run from Shinagawa to Nagoya. A subsequent extension to Osaka is planned to be completed by 2045. The planned travel time from Shinagawa to Shin-Osaka is 1 hour 7 minutes. Currently the Tokaido Shinkansen has a minimum connection time of 2 hours 19 minutes.[51]

While the government has granted approval[52] for the shortest route between Tokyo and Nagoya, some prefectural governments, particularly Nagano, lobbied to have the line routed farther north to serve the city of Chino and either Ina or Kiso-Fukushima. However, that would increase both the travel time (from Tokyo to Nagoya) and the cost of construction.[53] JR Central has confirmed it will construct the line through Kanagawa Prefecture, and terminate at Shinagawa Station.

The route for the Nagoya to Osaka section is also contested. It is planned to go via Nara, about 40 km south of Kyoto. Kyoto is lobbying to have the route moved north and be largely aligned with the existing Tokaido Shinkansen, which services Kyoto and not Nara.[54]

Mini-Shinkansen

Mini-shinkansen (ミニ新幹線) is the name given to the routes where former narrow gauge lines have been converted to standard gauge to allow Shinkansen trains to travel to cities without the expense of constructing full Shinkansen standard lines.

Two mini-shinkansen routes have been constructed: the Yamagata Shinkansen and Akita Shinkansen. Shinkansen services to these lines traverse the Tohoku Shinkansen line from Tokyo before branching off to traditional main lines. On both the Yamagata/Shinjo and Akita lines, the narrow gauge lines were regauged, resulting in the local services being operated by standard gauge versions of 1,067 mm gauge suburban/interurban rolling stock. On the Akita line between Omagari and Akita, one of the two narrow gauge lines was regauged, and a section of the remaining narrow gauge line is dual gauge, providing the opportunity for Shinkansen services to pass each other without stopping.

The maximum speed on these lines is 130 km/h, however the overall travel time to/from Tokyo is improved due to the elimination of the need for passengers to change trains at Fukushima and Morioka respectively.

As the Loading gauge (size of the train that can travel on a line) was not altered when the rail gauge was widened, only Shinkansen trains specially built for these routes can travel on the lines. At present they are the E3 and E6 series trains.

Whilst no further Mini-shinkansen routes have been proposed to date, it remains an option for providing Shinkansen services to cities on the narrow gauge network.

Gauge Change Train

This is the name for the concept of using a single train that is specially designed to travel on both 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) narrow gauge railway lines and the 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge used by Shinkansen train services in Japan. The trucks/bogies of the Gauge Change Train (GCT) allow the wheels to be unlocked from the axles, narrowed or widened as necessary, and then relocked. This allows a GCT to traverse both standard gauge and narrow gauge tracks without the expense of regauging lines.

Three test trains have been constructed, with the second set having completed reliability trials on the Yosan Line east of Matsuyama (in Shikoku) in September 2013. The third set was undertaking gauge changing trials at Shin-Yatsushiro Station (on Kyushu), commencing in 2014 for a proposed three-year period, however testing was suspended in December 2014 after accumulating approximating 33,000 km, following the discovery of defective thrust bearing oil seals on the bogies.[55] The train was being trialled between Kumamoto, travelling on the narrow gauge line to Shin-Yatsushiro, where a gauge changer has been installed, so the GCT could then be trialled on the Shinkansen line to Kagoshima. It was anticipated the train would travel approximately 600,000 km over the three-year trial.

A new "full standard" Shinkansen line is under construction from Takeo Onsen to Nagasaki, with the Shin-Tosu – Takeo Onsen section of the Kyushu Shinkansen branch to remain narrow gauge. GCTs were proposed to provide the Shinkansen service from the line's scheduled opening in March 2023, however with the GCT now being unavailable for service until at least 2025, other options are being considered, such as a 'relay' service.[49]

List of lines

The main Shinkansen lines are:

| Line | Start | End | Length | Operator | Opened | Annual passengers[56] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km | mi | ||||||

| Tōkaidō Shinkansen | Tokyo | Shin-Osaka | 515.4 | 320.3 | JR Central | 1964 | 143,015,000 |

| Sanyō Shinkansen | Shin-Osaka | Hakata | 553.7 | 344.1 | JR West | 1972–1975 | 64,355,000 |

| Tōhoku Shinkansen | Tokyo | Shin-Aomori | 674.9 | 419.4 | JR East | 1982–2010 | 76,177,000 |

| Jōetsu Shinkansen | Ōmiya | Niigata | 269.5 | 167.5 | 1982 | 34,831,000 | |

| Hokuriku Shinkansen | Takasaki | Kanazawa | 345.4 | 214.6 | JR East and JR West | 1997–2015 | 9,420,000 |

| Kyushu Shinkansen | Hakata | Kagoshima-Chūō | 256.8 | 159.6 | JR Kyushu | 2004–2011 | 12,143,000 |

| Hokkaido Shinkansen | Shin-Aomori | Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto | 148.9 | 92.5 | JR Hokkaido | 2016 | |

In practice, the Tokaido, Sanyo and Kyushu lines form a contiguous west/southbound line from Tokyo, as train services run between the Tokaido and Sanyo lines and between the Sanyo and Kyushu lines, though the lines are operated by different companies.

The Tokaido Shinkansen is not physically connected to the lines of the Tohoku Shinkansen at Tokyo Station. Therefore, there is no through service between those lines. All northbound services from Tokyo travel along the Tohoku Shinkansen until at least Ōmiya.

Two further lines, known as Mini-shinkansen, have also been constructed by re-gauging and upgrading existing sections of line:

There are two standard-gauge lines not technically classified as Shinkansen lines but with Shinkansen services:

- Hakata Minami Line (Hakata – Hakata-Minami)

- Gala-Yuzawa Line – technically a branch of the Jōetsu Line – (Echigo-Yuzawa – Gala-Yuzawa)

Future lines

Many Shinkansen lines were proposed during the boom of the early 1970s but have yet to be constructed. These are called Seibi Shinkansen (整備新幹線) or planned Shinkansen. One of these lines, the Narita Shinkansen to Narita Airport, was officially cancelled, but a few remain under development.

- Hokuriku Shinkansen extension from Kanazawa to Tsuruga is under construction and is scheduled to open in 2023. Between Hakusan Depot near Kanazawa and Tsuruga, the Fukui Shinkansen station was constructed in conjunction with the rebuilding of the adjoining conventional (narrow gauge) line station in anticipation of construction of the line to Osaka. The extension of the line to Osaka is proposed, with the route via Obama and Kyoto selected by the government on 20 December 2016.[43] Construction is proposed to commence in 2030, and take 15 years.

- Construction of the Kyushu Shinkansen branch from Shin-Tosu to Nagasaki, known as the Nagasaki Route (長崎ルート) or Nishi-Kyushu Route (西九州ルート), started in 2008. The branch will be partially built to full Shinkansen standards (Takeo Onsen – Nagasaki) with the existing narrow-gauge line from Shin-Tosu – Takeo Onsen to remain as narrow-gauge track. Gauge Change Trains and/or 'relay' services are to be provided on this route.[49]

- Hokkaido Shinkansen from Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto to Sapporo is under construction and scheduled to open by March 2031.[5]

- Chuo Shinkansen (Tokyo–Nagoya–Osaka) is a planned maglev line. JR Central has announced a 2027 target date for the line from Tokyo to Nagoya, with the extension to Osaka proposed to open in 2045. Construction of the project commenced in 2014.

The following lines were also proposed in the 1973 plan, but have subsequently been shelved indefinitely.

- Hokkaido Shinkansen northward extension: Sapporo–Asahikawa

- Hokkaido South Loop Shinkansen (北海道南回り新幹線 Hokkaidō Minami-mawari Shinkansen): Oshamanbe–Muroran–Sapporo

- Uetsu Shinkansen (羽越新幹線): Toyama–Niigata–Aomori

- Toyama–Jōetsu-Myōkō exists as part of the Hokuriku Shinkansen, and Nagaoka–Niigata exists as part of the Jōetsu Shinkansen, with provisions for the Uetsu Shinkansen at Nagaoka; Ōmagari–Akita exists as part of the Akita Shinkansen, but as a "Mini-Shinkansen" upgrade of existing conventional line, it does not meet the requirements of the Basic Plan.

- Ōu Shinkansen (奥羽新幹線): Fukushima–Yamagata–Akita

- Fukushima–Shinjō and Ōmagari–Akita exist as the Yamagata Shinkansen and Akita Shinkansen, respectively, but as "Mini-Shinkansen" upgrades of existing track, they do not meet the requirements of the Basic Plan.

- Hokuriku-Chūkyō Shinkansen (北陸・中京新幹線): Nagoya–Tsuruga

- Sanin Shinkansen (山陰新幹線): Osaka–Tottori–Matsue–Shimonoseki

- Trans-Chūgoku Shinkansen (中国横断新幹線 Chūgoku Ōdan Shinkansen): Okayama–Matsue

- Shikoku Shinkansen (四国新幹線): Osaka–Tokushima–Takamatsu–Matsuyama–Ōita

- Trans-Shikoku Shinkansen (四国横断新幹線 Shikoku Ōdan Shinkansen): Okayama–Kōchi–Matsuyama

- East Kyushu Shinkansen (東九州新幹線 Higashi-Kyushu Shinkansen): Fukuoka–Ōita–Miyazaki–Kagoshima

- Trans-Kyushu Shinkansen (九州横断新幹線 Kyushu Ōdan Shinkansen): Ōita–Kumamoto

In addition, the Basic Plan specified that the Jōetsu Shinkansen should start from Shinjuku, not Tokyo Station, which would have required building an additional 30 km of track between Shinjuku and Ōmiya. While no construction work was ever started, land along the proposed track, including an underground section leading to Shinjuku Station, remains reserved. If capacity on the current Tokyo–Ōmiya section proves insufficient, at some point, construction of the Shinjuku–Ōmiya link may be reconsidered.

The Narita Shinkansen project to connect Tokyo to Narita International Airport, initiated in the 1970s but halted in 1983 after landowner protests, has been officially cancelled and removed from the Basic Plan governing Shinkansen construction. Parts of its planned right-of-way were used by the Narita Sky Access Line which opened in 2010. Although the Sky Access Line uses standard-gauge track, it was not built to Shinkansen specifications and there are no plans to convert it into a full Shinkansen line.

In December 2009, then transport minister Seiji Maehara proposed a bullet train link to Haneda Airport, using an existing spur that connects the Tōkaidō Shinkansen to a train depot. JR Central called the plan "unrealistic" due to tight train schedules on the existing line, but reports said that Maehara wished to continue discussions on the idea.[57] The current minister has not indicated whether this proposal remains supported. While the plan may become more feasible after the opening the Chuo Shinkansen (sometimes referred to as a bypass to the Tokaido Shinkansen) frees up capacity, construction is already underway for other rail improvements between Haneda and Tokyo station expected to be completed prior to the opening of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, so any potential Shinkansen service would likely offer only marginal benefit beyond that.

| Line | Speed | Length | Construction began/proposed | Expected start of revenue services | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km/h | mph | km | mi | |||

| Kyushu Shinkansen (West Kyushu Route) | 260 | 160 | 66.7 | 41.4 | 2009 | FY2022 |

| Hokuriku Shinkansen Phase 3 (Kanazawa – Tsuruga) | 260 | 160 | 120.7 | 75.0 | 2012 | FY2023 |

| Hokkaido Shinkansen Phase 2 (Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto – Sapporo) | 260 | 160 | 211.3 | 131.3 | 2012 | FY2030 |

| Hokuriku Shinkansen Phase 4 (Tsuruga - Obama - Kyoto - Shin-Osaka) | 260 | 160 | 2030 | FY2045 | ||

List of train models

Trains are up to sixteen cars long. With each car measuring 25 m (82 ft) in length, the longest trains are 400 m (1/4 mile) end to end. Stations are similarly long to accommodate these trains. Some of Japan's high-speed maglev trains are considered Shinkansen,[58] while other slower maglev trains (such as the Linimo maglev train line serving local community near the city of Nagoya in Aichi, Japan) are intended as alternatives to conventional urban rapid transit systems.

Passenger trains

Tokaido and Sanyo Shinkansen

- 0 series: The first Shinkansen trains which entered service in 1964. Maximum operating speed was 220 km/h (135 mph). More than 3,200 cars were built. Withdrawn in December 2008.

- 100 series: Entered service in 1985, and featured bilevel cars with restaurant car and compartments. Maximum operating speed was 230 km/h (145 mph). Later used only on Sanyo Shinkansen Kodama services. Withdrawn in March 2012.

- 300 series: Entered service in 1992, initially on Nozomi services with maximum operating speed of 270 km/h (170 mph). Withdrawn in March 2012.

- 500 series: Introduced on Nozomi services in 1997, with an operating speed of 300 km/h (185 mph). Since 2008, sets have been shortened from 16 to 8 cars for use on Sanyo Shinkansen Kodama services.

- 700 series: Introduced in 1999, with maximum operating speed of 285 km/h (175 mph). Now used primarily on Hikari and Kodama services.

- N700 series: The most recently introduced type on the Tokaido and Sanyo Shinkansen, in service since 2007, with a maximum operating speed of 300 km/h (185 mph).

Kyushu Shinkansen

- 800 series: In service since 2004 on Tsubame services, with a maximum speed of 260 km/h (160 mph).

- N700-7000/8000 series In service since March 2011 on Mizuho and Sakura services with a maximum speed of 300 km/h (185 mph).

Tohoku, Joetsu, and Hokuriku Shinkansen

- 200 series: The first type introduced on the Tohoku and Joetsu Shinkansen in 1982 and withdrawn in April 2013. Maximum speed was 240 km/h (150 mph). The final configuration was as 10-car sets. 12-car and 16-car sets also operated at earlier times.

- E1 series: Bilevel 12-car trains introduced in 1994 and withdrawn in September 2012. Maximum speed was 240 km/h (150 mph).

- E2 series: 8/10-car sets in service since 1997 with a maximum speed of 275 km/h (170 mph).

- E4 series: Bilevel 8-car trains in service since 1997 with a maximum speed of 240 km/h (150 mph).

- E5 series: 10-car sets in service since March 2011 with a maximum speed of 320 km/h (200 mph).

- E7 series: 12-car trains operated on the Hokuriku Shinkansen since March 2014, with a maximum speed of 260 km/h (160 mph).[59]

- W7 series: 12-car trains operated on the Hokuriku Shinkansen since March 2015, with a maximum speed of 260 km/h (160 mph).[59]

Yamagata and Akita Shinkansen

- 400 series: The first Mini-shinkansen type, introduced in 1992 on Yamagata Shinkansen Tsubasa services with a maximum speed of 240 km/h. Withdrawn in April 2010.

- E3 series: Introduced in 1997 on Akita Shinkansen Komachi and Yamagata Shinkansen Tsubasa services with a maximum speed of 275 km/h. Now operated solely on the Yamagata Shinkansen.

- E6 series: Introduced in March 2013 on Akita Shinkansen Komachi services, with a maximum speed of 300 km/h (185 mph), raised to 320 km/h (200 mph) in March 2014.

Hokkaido Shinkansen

- H5 series: 10-car sets entered service from March 2016 on the Hokkaido Shinkansen with a maximum speed of 320 km/h (200 mph).[60][61]

Taiwan High Speed Rail

- 700T series (Taiwan High Speed Rail, a.k.a. Taiwan Shinkansen): The first Shinkansen type exported outside Japan. 12-car trains based on 700 series entered service in 2007, with a maximum speed of 300 km/h (190 mph).

Experimental trains

- Class 1000 – 1961

- Class 951 – 1969

- Class 961 – 1973

- Class 962 – 1979

- 500-900 series "WIN350" – 1992

- Class 952/953 "STAR21" – 1992

- Class 955 "300X" – 1994

- Gauge Change Train – 1998 to present

- Class E954 "Fastech 360S" – 2004

- Class E955 "Fastech 360Z" – 2005

Maglev trains

Note that these trains were and currently are used only for experimental runs.

- LSM200 – 1972

- ML100 – 1972

- ML100A – 1975

- ML-500 – 1977

- ML-500R – 1979

- MLU001 – 1981

- MLU002 – 1987

- MLU002N – 1993

- MLX01 – 1996

- L0 series – 2012

Maintenance vehicles

- 911 Type diesel locomotive

- 912 Type diesel locomotive

- DD18 Type diesel locomotive

- DD19 Type diesel locomotive

- 941 Type (rescue train)

- 921 Type (track inspection car)

- 922 Type (Doctor Yellow sets T1, T2, T3)

- 923 Type (Doctor Yellow sets T4, T5)

- 925 Type (Doctor Yellow sets S1, S2)

- E926 Type (East i)

List of types of services

Originally intended to carry passenger and freight trains by day and night, the Shinkansen lines carry only passenger trains. The system shuts down between midnight and 06:00 every day for maintenance. The few overnight trains that still run in Japan run on the older narrow gauge network that the Shinkansen parallels.

Tōkaidō, Sanyō and Kyushu Shinkansen

Tōhoku, Hokkaido, Yamagata and Akita Shinkansen

Jōetsu Shinkansen

- Toki / Max Toki

- Tanigawa / Max Tanigawa

- Asahi / Max Asahi (discontinued)

Hokuriku Shinkansen

Speed records

Conventional wheeled

| Speed[62] | Train | Location | Date | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km/h | mph | ||||

| 200 | 120 | Class 1000 Shinkansen | Kamonomiya test track in Odawara, now part of Tōkaidō Shinkansen | 31 October 1962 | |

| 256 | 159 | Class 1000 Shinkansen | Kamonomiya test track | 30 March 1963 | Former world speed record for EMU trains. |

| 286 | 178 | Class 951 Shinkansen | Sanyō Shinkansen | 24 February 1972 | Former world speed record for EMU trains. |

| 319.0 | 198.2 | Class 961 Shinkansen | Oyama test track, now part of Tōhoku Shinkansen | 7 December 1979 | Former world speed record for EMU trains. |

| 325.7 | 202.4 | 300 series | Tōkaidō Shinkansen | 28 February 1991 | |

| 336.0 | 208.8 | 400 series | Jōetsu Shinkansen | 26 March 1991 | |

| 345.0 | 214.4 | 400 series | Jōetsu Shinkansen | 19 September 1991 | |

| 345.8 | 214.9 | 500-900 series "WIN350" | Sanyō Shinkansen | 6 August 1992 | |

| 350.4 | 217.7 | 500-900 series "WIN350" | Sanyō Shinkansen | 8 August 1992 | |

| 352.0 | 218.7 | Class 952/953 "STAR21" | Jōetsu Shinkansen | 30 October 1992 | |

| 425.0 | 264.1 | Class 952/953 "STAR21" | Jōetsu Shinkansen | 21 December 1993 | |

| 426.6 | 265.1 | Class 955 "300X" | Tōkaidō Shinkansen | 11 July 1996 | |

| 443.0 | 275.3 | Class 955 "300X" | Tōkaidō Shinkansen | 26 July 1996 | |

Maglev trains

| Speed | Train | Location | Date | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km/h | mph | ||||

| 550 | 340 | MLX01 | Chūō Shinkansen (Yamanashi test track) | 24 December 1997 | Former world speed record |

| 552 | 343 | 14 April 1999 | |||

| 581 | 361 | 2 December 2003 | |||

| 590 | 370 | L0 series | 16 April 2015[63] | ||

| 603 | 375 | 21 April 2015[7] | World speed record | ||

Competition with air

Compared with air transport, the Shinkansen has several advantages, including scheduling frequency and flexibility, punctual operation, comfortable seats, and convenient city-centre terminals.

Shinkansen fares are generally competitive with domestic air fares. From a speed and convenience perspective, the Shinkansen's market share has surpassed that of air travel for journeys of less than 750 km, while air and rail remain highly competitive with each other in the 800–900 km range and air has a higher market share for journeys of more than 1,000 km.[64]

- Tokyo – Nagoya (342 km), Tokyo – Sendai (325 km), Tokyo – Hanamaki (Morioka) (496 km), Tokyo – Niigata (300 km): There were air services between these cities, but they were withdrawn after Shinkansen services started. Shinkansen runs between these cities in about two hours or less.

- Tokyo – Osaka (515 km): Shinkansen is dominant because of fast (2 hours 30 minutes) and frequent service (up to every 10 minutes by Nozomi); however, air travel has a certain share (~20–30%).

- Tokyo – Okayama (676 km), Tokyo – Hiroshima (821 km): Shinkansen is reported to have increased its market share from ~40% to ~60% over the last decade.[65] The Shinkansen takes about three to four hours and there are Nozomi trains every 30 minutes, but airlines may provide cheaper fares, attracting price-conscious passengers.

- Tokyo – Fukuoka (1,069 km): The Shinkansen takes about five hours on the fastest Nozomi, and discount carriers have made air travel far cheaper, so most people choose air. Additionally, unlike many cities, there is very little convenience advantage for the location of the Shinkansen stations of the two cities as Fukuoka Airport is located near the central Tenjin district, and Fukuoka City Subway Line 1 connects the Airport and Tenjin via Hakata Station and Haneda Airport is similarly conveniently located.

- Osaka – Fukuoka (554 km): One of the most competitive sections. The Shinkansen takes about two and a half hours by Nozomi or Mizuho, and the JR West Hikari Rail Star or JR West/JR Kyushu Sakura trains operate twice an hour, taking about 2 hours and 40 minutes between the two cities. Again the location of the airports involved helps with the popularity of air travel.

- Tokyo – Aomori (675 km): The fastest Shinkansen service between these cities is 3 hours. JAL is reported to have reduced the size of planes servicing this route since the Shinkansen extension opened in 2010.[65]

- Tokyo – Hokuriku (345 km): The fastest Shinkansen service between these cities is 2½ hours. ANA is reported to have reduced the number of services from Tokyo to Kanazawa and Toyama from 6 to 4 per day since the Shinkansen extension opened in 2015. The share of passengers travelling this route by air is reported to have dropped from 40% to 10% in the same period.[44]

Shinkansen technology outside Japan

Railways using Shinkansen technology are not limited to those in Japan.

Existing

Taiwan

Taiwan High Speed Rail operates 700T Series sets built by Kawasaki Heavy Industries.

China

The China Railways CRH2, built by CSR Sifang Loco & Rolling stocks corporation, with the license purchased from a consortium formed of Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Mitsubishi Electric Corporation, and Hitachi, is based on the E2-1000 series design.

United Kingdom

Class 395 EMUs were built by Hitachi based on Shinkansen technology for use on high-speed commuter services in Britain on the High Speed 1 line.

Under contract

United States

In 2014, it was announced[66] that Texas Central Railway would build a 300 mile long line using the N700 series rolling stock. The trains will run at over 320 km/h (200 mph).[67]

India

In December 2015, India and Japan signed an agreement for the construction of India's first high speed rail link connecting Mumbai to Ahmedabad. Funded primarily through Japanese soft loans, the link is expected to cost up to $18.6b and should be operational in about 7 years.[68][69]

This followed India and Japan conducting feasibility studies on high-speed rail and dedicated freight corridors.

The Indian Ministry of Railways' white-paper Vision 2020[70] submitted to Indian Parliament by Railway Minister Mamata Banerjee on 18 December 2009[71] envisages the implementation of regional high-speed rail projects to provide services at 250–350 km/h.

During Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's visit to Tokyo in December 2006, Japan assured cooperation with India in creating a high-speed link between New Delhi and Mumbai.[72] In January 2009, the then Railway Minister Lalu Prasad rode a bullet train travelling from Tokyo to Kyoto.[73]

In December 2013 a Japanese consortium was appointed to undertake a feasibility study of a ~500 km high-speed line between Mumbai and Ahmedabad by July 2015.[74] A total of 7 high-speed lines are in planning stages in India, and Japanese firms have now succeeded in winning contracts to prepare feasibility studies for three of the lines.

The National High Speed Rail Corporation (NHSRC) was incorporated in 2017 to manage all HSR related activities in India. Under its management, a High Speed Rail Training Institute is being developed with Japanese assistance in Vadodara, Gujarat. After the laying of the foundation stone for the Mumbai and Ahmedabad by the Prime Ministers of India and Japan in September 2017, work began on preparatory surveys along the 508 km (316 mi) route. The route consists of approximately 477 km (296 mi) elevated viaduct through 11 districts of Gujarat and four districts of Maharashtra, a 21 km (13 mi) deep-sea tunnel starting from BKC in Mumbai, and approximately 10 km (6.2 mi) of at-grade alignment near the other terminus at Sabarmati, near Ahmedabad. Most of the civil works for the elevated viaduct shall be handled by Indian companies, while the deep-sea tunnel at Mumbai will be handled by a Japanese consortium (along with other technical aspects, such as safety, electricals, communication systems, signaling, and rolling stock). BHEL of India and Kawasaki Heavy Industries of Japan have entered into a technology collaboration agreement to build and assemble the rolling stock (of E5 series vintage) in India. Other potential joint ventures are being explored under the patronage of NHSRC. The line is expected to operational by 2023.

Proposed subject to funding

Thailand

Japan will provide Shinkansen technology for a high-speed rail link between Bangkok and the northern city of Chiang Mai under an agreement reached with Thailand on 27 May 2015. Total project costs are estimated in excess of 1 trillion yen ($8.1 billion). Several hurdles remain, however, including securing the funding. If the project is realized, it would mark the fifth time Shinkansen technology has been exported.[75]

Potential opportunities

Australia

A private organisation dedicated in aiding the Australian Government in delivering high speed rail: Consolidated Land and Rail Australia has considered purchasing Shinkansen technology or SC Maglev rolling stock for a potential Melbourne-Canberra-Sydney-Brisbane line.[76] A business case has been prepared for the government by Infrastructure Australia, and is awaiting confirmation of the project within the next federal budget release in 2018.

United States and Canada

The U.S. Federal Railroad Administration is in talks with a number of countries with high-speed rail, notably Japan, France and Spain. On 16 May 2009, FRA Deputy Chief Karen Rae expressed hope that Japan would offer its technical expertise to Canada and the United States. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood indicated interest in test riding the Japanese Shinkansen in 2009.[77][78]

On 1 June 2009, JR Central Chairman, Yoshiyuki Kasai, announced plans to export both the N700 Series Shinkansen high-speed train system and the SCMaglev to international export markets, including the United States and Canada.[79]

Brazil

Japan is promoting its Shinkansen technology to the Government of Brazil for use on the planned high-speed rail set to link Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Campinas.[80] On 14 November 2008, Japanese Prime Minister Tarō Asō and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva talked about this rail project. President Lula asked a consortium of Japanese companies to participate in the bidding process. Prime Minister Aso concurred on the bilateral cooperation to improve rail infrastructure in Brazil, including the Rio–São Paulo–Campinas high-speed rail line.[81] The Japanese consortium includes the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Mitsui & Co., Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Kawasaki Heavy Industries and Toshiba.[82][83]

Vietnam

Vietnam Railways was considering the use of Shinkansen technology for high-speed rail between the capital Hanoi and the southern commercial hub of Ho Chi Minh City, according to the Nihon Keizai Shimbun, citing an interview with Chief Executive Officer Nguyen Huu Bang. The Vietnamese government had already given basic approval for the Shinkansen system, although it still requires financing and formal consent from the prime minister. Vietnam rejected a funding proposal in 2010, so funding for the $56 billion project is uncertain. Hanoi was exploring additional Japanese funding Official Development Assistance as well as funds from the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. The 1,560-kilometre (970 mi) line would replace the current colonial-era rail line. Vietnam hopes to launch high-speed trains by 2020 and plans to start by building three sections, including a 90-kilometre stretch between the central coastal cities of Da Nang and Huế, seen as potentially most profitable. Vietnam Railways had sent engineers to Central Japan Railway Company for technical training.[84][85]

See also

References

- ↑ Joe Pinsker (6 October 2014). "What 50 Years of Bullet Trains Have Done for Japan". The Atlantic. The Atlantic Monthly Group. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Philip Brasor and Masako Tsubuku (30 September 2014). "How the Shinkansen bullet train made Tokyo into the monster it is today". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ "About the Shinkansen Outline". JR Central. March 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ "JR-EAST:Fact Sheet Service Areas and Business Contents" (PDF). East Japan Railway Company. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Sato, Yoshihiko (16 February 2016). "Hokkaido Shinkansen prepares for launch". International Railway Journal. Simmons-Boardman Publishing Inc. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ↑ "Tohoku Shinkansen Speed Increase: Phased speed increase after the extension to Shin-Aomori Station". East Japan Railway Company. 6 November 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Japan's maglev train breaks world speed record with 600km/h test run". The Guardian. United Kingdom: Guardian News and Media Limited. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ↑ Central Japan Railway Company Annual Report 2017 (PDF) (Report). Central Japan Railway Company. 2017. p. 23. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "KTX vs 新幹線 徹底比較". Whhh.fc2web.com. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "About the Shinkansen". Central Japan Railway Company. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ chinanews. "2017年中国铁路投资8010亿元 投产新线3038公里-中新网". www.chinanews.com. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- ↑ "China High Speed Train Development and Investment". Thechinaperspective.com. 20 November 2012. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Shinkansen". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Shinsaku Matsuyama (2015). 鉄道の「鉄」学: 車両と軌道を支える金属材料のお話 [Iron for Iron Horses: The Story of the Metals Used in Rolling Stock and Railway Tracks]. Tokyo: Ohmsha Ltd. ISBN 9784274217630.

- ↑ Hood, Christopher P. (2007). Shinkansen – From Bullet Train to Symbol of Modern Japan. Routledge, London. pp. 18–43. ISBN 978-0-415-32052-8.

- 1 2 3 Smith, Roderick A. (2003). "The Japanese Shinkansen". The Journal of Transport History. Imperial College, London. 24/2: 222–236.

- ↑ Fukada, Takahiro, "Shinkansen about more than speed", The Japan Times, 9 December 2008, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Features and Economic and Social Effects of The Shinkansen". Jrtr.net. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ↑ "Half century on the shinkansen - The Japan Times". japantimes.co.jp.

- ↑ "Shinkansen comes to York". Railway Gazette. 1 August 2001. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ↑ "Railway Modernization and Shinkansen". Japan Railway & Transport Review. 30 April 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ Miura, S., Takai, H., Uchida, M., and Fukada, Y. The Mechanism of Railway Tracks. Japan Railway & Transport Review, 15, 38-45, 1998

- ↑ Ando, Katsutoshi et. al (2001). "Development of Slab Tracks for Hokuriku Shinkansen Line". Quarterly Report of RTRI. 42 (1): 35–41. doi:10.2219/rtriqr.42.35. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Central Japan Railway Company Annual Report 2016" (PDF). p. 18. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ↑ "Safety". Central Japan Railway Company. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ "Railway to pay for 1995 fatality; Shinkansen victim's parents win 49 million yen in damages", The Japan Times, March 8, 2001

- ↑ "Shinkansen (Japanese Bullet Trains) and Maglev Magnetic Trains". Archived from the original on 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "Japan bullet train passenger starts fire injuring eight". BBC News Online. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ "Report on Niigata Chuetsu Earthquake" (PDF). (43.8 KB)

- ↑ "High-speed bullet train derails in Japan: Media". The Sunday Times. Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings Ltd. Co. 2 March 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ↑ "Crack found in Shinkansen trainset bogie". Railway Gazette. 13 December 2017. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "Sensible Politics and Transport Theories?". Jrtr.net. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ↑ "新幹線鉄道騒音に係る環境基準について(昭和50年環境庁告示) The Environmental Regulation of Shinkansen Noise Pollution (1975, Environmental Agency) (Japanese)". Env.go.jp. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ↑ "国土交通省鉄道輸送統計年報(平成19年度)".

- ↑ "KTX vs 新幹線 徹底比較". Whhh.fc2web.com. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- ↑ http://www.mlit.go.jp/common/000232384.pdf

- ↑ "Taiwan HSR operator pitches restructuring idea to shareholders|WCT". Wantchinatimes.com. 2014-06-28. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- ↑ "월별 일반철도 역간 이용인원". Ktdb.go.kr. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- ↑ 2890 (2015-01-30). "铁路2014年投资8088亿元 超额完成全年计划-财经-人民网". Finance.people.com.cn. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- ↑ グループ経営構想Ⅴ [Group Business Vision V] (PDF) (in Japanese). Japan: East Japan Railway Company. 30 October 2012. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- 1 2 Nakada, Ayako (4 December 2015). "Bullet train linking Tokyo and Hokkaido unable to hit sub 4-hour target". ajw.asahi.com. Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ↑ "Construction approved on 3 new bullet train extensions". 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- 1 2 UK, DVV Media. "Hokuriku extension route agreed".

- 1 2 "Japan's newest bullet train line has busy first year- Nikkei Asian Review".

- ↑ 京都新聞. "北陸新幹線新駅「松井山手」検討 京都-新大阪南回り案 : 京都新聞". www.kyoto-np.co.jp.

- ↑ 日本テレビ. "北陸新幹線"京田辺市ルート"最終調整へ|日テレNEWS24".

- ↑ Barrow, Keith. "Talks begin on Hokuriku Shinkansen extension".

- ↑ http://www.mlit.go.jp/common/000215188.pdf

- 1 2 3 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- 1 2 "Promoting the Tokaido Shinkansen Bypass by the Superconducting Maglev system" (PDF). english.jr-central.co.jp. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ "Maglev car design unveiled". The Japan Times. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Most direct line for maglev gets panel OK". The Japan Times. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ↑ "LDP OKs maglev line selections". The Japan Times. 21 October 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ↑ "Economy, prestige at stake in Kyoto-Nara maglev battle". The Japan Times. 3 May 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ "鉄道輸送統計調査(平成23年度、国土交通省) Rail Transport Statistics (2011, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport) (Japanese)". Mlit.go.jp. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Maehara sounds out JR Tokai over shinkansen link for Haneda airport". Japan Today. 28 December 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ↑ "FY2009 Key Measures and Capital Investment - Central Japan Railway Company". Central Japan Railway Company. 27 March 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- 1 2 北陸新幹線用の新型車両について [New trains for Hokuriku Shinkansen] (PDF). Press release (in Japanese). Japan: JR East & JR West. 4 September 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ 北海道新幹線用車両について [Hokkaido Shinkansen Train Details] (PDF). News release (in Japanese). Japan: Hokkaido Railway Company. 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ 北海道新幹線「H5系」、内装には雪の結晶も [Hokkaido Shinkansen "H5 series" - Interiors to feature snowflake design]. Yomiuri Online (in Japanese). Japan: The Yomiuri Shimbun. 16 April 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-04-15. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ Semmens, Peter (1997). High Speed in Japan: Shinkansen - The World's Busiest High-speed Railway. Sheffield, UK: Platform 5 Publishing. ISBN 1-872524-88-5.

- ↑ リニア「L0系」、世界最高の590キロ記録 [L0 series maglev sets world speed record of 590 km/h]. Yomiuri Online (in Japanese). Japan: The Yomiuri Shimbunl. 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-04-16. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Shiomi, Eiji. "Do Faster Trains Challenge Air Carriers?". Japan Railway & Transport Review. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Japanese airlines facing threat from below- Nikkei Asian Review". Asia.nikkei.com. 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ Dixon, Scott (2 August 2014). "Texas to get shinkansen system". Retrieved 16 September 2017 – via Japan Times Online.

- ↑ "LEARN THE FACTS - Texas Central". Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "India bites the $18.6 billion high speed bullet". 13 December 2015.

- ↑ UK, DVV Media. "India and Japan sign high speed rail memorandum".

- ↑ "Indian Railways 2020 Vision - Government of India Ministry of Railways (Railway Board) December, 2009" (PDF).

- ↑ India getting ready for bullet trains - Central Chronicle Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "India seeks nuclear help in Japan". 14 December 2006 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "Bullet Trains - Lalu Prasad Yadav - Railway Minister - Shinkansen - Japan - Tokyo - Kyoto - Mumbai".

- ↑ :日本経済新聞 (in Japanese). Nikkei.com. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ YO NOGUCHI/ Staff Writer. "Japan to provide Shinkansen technology to Thailand - AJW by The Asahi Shimbun". Ajw.asahi.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ "Consolidated Land and Rail Australia Pty Ltd". www.clara.com.au.

- ↑ "U.S. wants to study shinkansen technology". Kyodo News. 16 May 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ↑ "U.S. railroad official seeks Japan's help". United Press International. 16 May 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ↑ "JR Tokai chief urges U.S. and Canada together to introduce Japan's N700 bullet rail system". JapanToday. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ↑ ブラジルに新幹線導入を=日本政府・民間の動き活発化=大統領来日時に働きかけへ=新時代の友好協力の柱に (in Japanese). The Nikkey Shimbun. 31 January 2008. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ↑ 日ブラジル首脳会談(概要) (in Japanese). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 14 November 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ↑ ブラジルに新幹線進出狙う 三井物産、建設に応札へ (in Japanese). Kyodo News. 12 August 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ↑ ブラジルに新幹線売り込み】日本勢、高速鉄道建設で各国と競合 (in Japanese). The Nikkei Net. 17 June 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ ベトナム縦断で新幹線 国営鉄道会長、2020年部分開業目指す (in Japanese). The Nikkei Net. 13 August 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ↑ "Vietnam plans Japanese bullet train link". AFP. 13 August 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shinkansen. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Rail travel in Japan. |

- Biting the Bullet: What we can learn from the Shinkansen, discussion paper by Christopher Hood in the electronic journal of contemporary Japanese studies, 23 May 2001

- East meets West, a story of how the Shinkansen brought Tokyo and Osaka closer together.

- Bullet on wheels, a travel report by Vinod Jacob 19 August 2005

- Shinkansen Wheelchair Accessibility, review for riders with disabilities.