Gurmukhi

| Gurmukhi | |

|---|---|

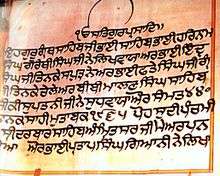

A handwritten Guru Granth Sahib in Gurmukhī | |

| Type | |

| Languages | |

Time period | 16th century CE-present |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 |

Guru, 310 |

Unicode alias | Gurmukhi |

| U+0A00–U+0A7F | |

|

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmic script and its descendants |

|

Northern Brahmic

|

Gurmukhi (IPA: [ɡʊɾmʊkʰi]; Gurmukhi (the literal meaning being "from the Guru's mouth"): ਗੁਰਮੁਖੀ) is a Brahmic script modified, standardized and used by the second Sikh Guru, Guru Angad (1504–1552).[2][3][4] Gurmukhi is used by Sikh and Hindu Indian Punjabis to write the Punjabi language,[4] a language that is also written in Perso-Arabic Shahmukhi script by Muslim Punjabis in Pakistan and the Nāgarī script by Hindu Punjabis in India.[3][4]

The primary scripture of Sikhism, Guru Granth Sahib is written in Gurmukhī, in various dialects often coalesced under the generic title of Sant Bhasha.[5]

Modern Gurmukhī has thirty-eight consonants (akhar), 10 vowel symbols (lāga mātrā), two symbols for nasal sounds ( bindi and ṭippī), and one symbol which duplicates the sound of any consonant (addak). In addition, four conjuncts are used: three subjoined forms of the consonants Rara, Haha and Vava, and one half-form of Yayya. Use of the conjunct forms of Vava and Yayya is increasingly scarce in modern contexts.[2]

Origins

The Gurmukhi script has roots in the Brahmi script like most Indian, Tibetan, and Southeast Asian languages.[6] In a cursory look, the Gurmukhi script appears different from other Indic scripts such as Bengali, Oriya, Tibetan or Devanagari, but a closer examination reveals they are similar except for angles and structural emphasis.[7]

Notable features:

- It is an abugida in which all consonants have an inherent vowel. Diacritics, which can appear above, below, before or after the consonant they belong to, are used to change the inherent vowel.

- When they appear at the beginning of a syllable, vowels are written as independent letters.

- When certain consonants occur together, special conjunct symbols are used which combine the essential parts of each letter.

- Punjabi is a tonal language with three tones. These are indicated in writing using the voiced aspirated consonants (gh, dh, bh, etc.) and the intervocalic h.

There are two major theories on how the Proto-Gurmukhī script emerged in the 15th century. G.B. Singh (1950), while quoting al-Biruni's Ta'rikh al-Hind (1030 CE), says that the script evolved from Ardhanagari. Al-Biruni writes that the Ardhanagari script was used in Bathinda and western parts of the Punjab in the 10th century. For some time, Bathinda remained the capital of the kingdom of Bhati Rajputs of the Pal clan, who ruled North India before the Muslims occupied the country. According to al-Biruni, Ardhanagari was a mixture of devanagari used in Ujjain and Malwa and Siddha Matrika or the last stage of Siddhaṃ script, a variant of the Śāradā script used in Kashmir. This theory is confusing as Gurmukhī characters have a very close resemblance with "Siddh Matrika" inscriptions found at some sacred wells in Punjab as G.B Singh notes, one being the hathur inscription dating to just before the birth of Guru Nanak. Siddh Matrika seems to have been the prevalent script for devotional writings in Punjab right up to the founding of Sikhism, after which its successor Gurmukhī appears.

Pritam Singh (1992) has also traced the origins of Gurmukhī to the Siddha Matrika. "Siddha Matrika" along with its sister Takri alphabet has its origins in the Śāradā script of Kashmir.

Tarlochan Singh Bedi (1999) writes that the Gurmukhī script developed in the 10-14th centuries from the Devasesha stage of the Śāradā script, the intermediate phase being Siddha Matrika, before the final evolution into Gurmukhī. His argument is that from the 10th century, regional differences started to appear between the Śāradā script used in Punjab, the Hill States (partly Himachal Pradesh) and Kashmir. The regional Śāradā script evolved from this stage until the 14th century, when it starts to appear in the form of Gurmukhī. Indian epigraphists call this stage Devasesha, while Bedi prefers the name Pritham Gurmukhī or Proto-Gurmukhī.

The Sikh gurus adopted proto-Gurmukhī to write the Guru Granth Sahib, the religious scriptures of the Sikhs. Other contemporary scripts used in the Punjab were Takri and the Laṇḍā scripts. The Takri alphabet developed through the Devasesha stage of the Śāradā script and is found mainly in the Hill States such as Chamba, Himachal Pradesh, where it is called Chambyali, and in Jammu Division, where it is known as Dogri. The local Takri variants got the status of official scripts in some of the Punjab Hill States, and were used for both administrative and literary purposes until the 19th century. After 1948, when Himachal Pradesh was established as an administrative unit, the local Takri variants were replaced by Devanagari.

Meanwhile, the mercantile scripts of Punjab known as the Laṇḍā scripts were normally not used for literary purposes. Landa means alphabet "without tail", implying that the script did not have vowel symbols. In Punjab, there were at least ten different scripts classified as Laṇḍā, Mahajani being the most popular. The Laṇḍā scripts were used for household and trade purposes. Compared to the Laṇḍā, Sikh Gurus favoured the use of Proto-Gurmukhī, because of the difficulties involved in pronouncing words without vowel signs.

The usage of Gurmukhī letters in Guru Granth Sahib meant that the script developed its own orthographical rules. In the following epochs, Gurmukhī became the prime script applied for literary writings of the Sikhs. Later in the 20th century, the script was given the authority as the official script of the Punjab, India.[3][4]

Gurmukhī Punjabi

The word Gurmukhī translates as "from the Mouth of the Guru,".

Guru Angad is credited in the Sikh tradition with the Gurmukhi script, which is now the standard writing script for Punjabi language in India,[8] in contrast to Punjabi language in Pakistan where now an Arabic script called Nastaliq is the standard.[3] The original Sikh scriptures and most of the historic Sikh literature have been written in the Gurmukhi script.[8]

Alphabet

Consonants

The Gurmukhī alphabet contains thirty-five letters. The first three are distinct because they form the basis for vowels and are not consonants, and except for æṛa are never used on their own. See the section on vowels for further details.

| Name | Pron.(IPA) | Name | Pron.(IPA) | Name | Pron.(IPA) | Name | Pron.(IPA) | Name | Pron.(IPA) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ੳ | uɽɑ | – | ਅ | æɽɑ | ə | ੲ | iɽi | – | ਸ | səsːɑ | sə | ਹ | ɦɑɦɑ | ɦə |

| ਕ | kəkːɑ | kə | ਖ | kʰəkʰːɑ | kʰə | ਗ | gəgːɑ | ɡə | ਘ | kə̀gːɑ | kə̀ | ਙ | ŋɑŋːɑ̃ | ŋə |

| ਚ | t͡ʃət͡ʃːɑ | t͡ʃə | ਛ | t͡ʃʰət͡ʃʰːɑ | t͡ʃʰə | ਜ | d͡ʒəd͡ʒːɑ | d͡ʒə | ਝ | t͡ʃə̀d͡ʒːɑ | t͡ʃə̀ | ਞ | ɲəɲːɑ̃ | ɲə |

| ਟ | ʈɑtt:a | ʈə | ਠ | ʈʰəʈʰːɑ | ʈʰə | ਡ | ɖəɖːɑ | ɖə | ਢ | ʈə̀ɖːɑ | ʈə̀ | ਣ | ɳɑɳɑ | ɳə |

| ਤ | t̪ət̪ːɑ | t̪ə | ਥ | t̪ʰət̪ʰːɑ | t̪ʰə | ਦ | d̪əd̪ːɑ | d̪ə | ਧ | t̪ə̀d̪ːɑ | t̪ə̀ | ਨ | nənːɑ | nə |

| ਪ | pəpːɑ | pə | ਫ | pʰəpʰːɑ | pʰə | ਬ | bəbːɑ | bə | ਭ | pə̀bːɑ | pə̀ | ਮ | məmːɑ | mə |

| ਯ | jəjːɑ | jə | ਰ | ɾɑɾɑ | ɾə | ਲ | ləlːɑ | lə | ਵ | ʋɑʋːɑ | ʋə | ੜ | ɽɑɽɑ | ɽə |

ਙ |ŋɑŋːɑ̃ | and ਞ |ɲəɲːɑ̃ | are rarely used. They cannot begin a syllable or be placed between two consonants, and occur most often as an allophone of n before specific consonant phonemes.

The pronunciation of ਵ will vary between v and w depending on the word.

- à – grave accent = tonal consonant.

- To differentiate between consonants, the Punjabi tonal consonants kà, chà, ṭà, tà, and pà are often transliterated in the way of the Hindi voiced aspirate consonants gha, jha, ḍha, dha, and bha respectively, although Punjabi does not have these sounds.

- Tones in Punjabi can be either rising or falling; in the pronunciation of Gurmukhī letters they are falling, hence the grave accent as opposed to the acute.

In addition to these, there are six consonants created by placing a dot (bindi) at the foot (pair) of the consonant (these are not present in Sri Guru Granth Sahib). These are used most often for loanwords, though not exclusively:

| Name | Pron.(IPA) | |

|---|---|---|

| ਸ਼ | səsːɑ pɛɾ bɪnd̪i | ʃə |

| ਖ਼ | kʰəkʰːɑ pɛɾ bɪnd̪i | xə |

| ਗ਼ | gəgːɑ pɛɾ bɪnd̪i | ɣə |

| ਜ਼ | d͡ʒəd͡ʒːɑ pɛɾ bɪnd̪i | zə |

| ਫ਼ | pʰəpʰːɑ pɛɾ bɪnd̪i | fə |

| ਲ਼ | ləlːɑ pɛɾ bɪnd̪i | ɭə |

|ləlːɑ pɛɾ bɪnd̪i| was only recently added to the Gurmukhī alphabet. It was not a part of the traditional orthography, the phonological difference between 'l' and 'ɭ' was not reflected in the script. Some sources do not consider it a separate letter.

"Subjoined" letters

Three "subscript" letters are utilised in Gurmukhī: forms of ਹ(h), ਰ(r), and ਵ(v). ਰ(r) and ਵ(v) are used to make consonant clusters and behave similarly; subjoined ਹ(h) raises tone.

- Subjoined ਰ(r): For example, the letter ਪ(p) with a regular ਰ(r) following it would yield the word ਪਰ pər ("but"), but with a subjoined ਰ would appear as ਪ੍ਰ- (prə-), resulting in a consonant cluster, as in the word ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧ (prəbə́nd̪, "management, government")

- Subjoined ਵ(v): somewhat less common in modern usage. For example, ਸ followed by a regular ਵ would yield ਸਵ- (səv-) as in the word ਸਵੇਰ (səvēr, "morning"), but with a subjoined ਵ would produce ਸ੍ਵ (svə-) as in the word ਸ੍ਵਰਗ (svərəg, "heaven")

- Subjoined ਹ(h): behaves the same way as the regular ਹ(h) in non-word-initial positions. The regular ਹ(h) is pronounced at the beginning of words but not in other positions, where it instead raises the tone. The difference in usage is that the regular ਹ is used after vowels and the subscript version when there is no vowel, and is attached to consonants.

- For example: the regular ਹ is used after vowels as in ਮੀਹ (transliterated as mih, to show tonality, mī́, "rain"). The subjoined ਹ(h) acts the same way but instead is used under consonants: ਚ(ch) followed by ੜ(ṛ) yields ਚੜ (chəṛ), but not until the rising tone is introduced via a subscript ਹ(h) does it properly spell the word ਚੜ੍ਹ (chə́ṛ, "climb").

Vowels

Gurmukhī is similar to Brahmi scripts in that all consonants are followed by an inherent 'a' sound (unless at the end of a word when the 'a' is usually dropped). This inherent vowel sound can be changed by using dependent vowel signs which attach to a bearing consonant. In some cases, dependent vowel signs cannot be used – at the beginning of a word or syllable for instance – and so an independent vowel character is used instead.

Independent vowels are constructed using three bearer characters: Ura (ੳ), Aira (ਅ) and Iri (ੲ). With the exception of Aira (which represents the vowel 'a') they are never used without additional vowel signs.

| Vowel | Transcription | IPA | Closest English equivalent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ind. | Dep. | with /k/ | Name | Usage | ||

| ਅ | (none) | ਕ | Muktā | a | [ə] | like a in about |

| ਆ | ਾ | ਕਾ | Kannā | ā | [ɑ] , [ä] | like a in car |

| ਇ | ਿ | ਕਿ | Sihārī | i | [ɪ] | like i in it |

| ਈ | ੀ | ਕੀ | Bihārī | ī | [i] | like i in litre |

| ਉ | ੁ | ਕੁ | Onkaṛ | u | [ʊ] | like u in put |

| ਊ | ੂ | ਕੂ | Dulankaṛ | ū | [u] | like oo as in food |

| ਏ | ੇ | ਕੇ | Lāvā̃ | ē | [e] | like e in Chile |

| ਐ | ੈ | ਕੈ | Dulāvā̃ | e | [ɛ] | like e in sell |

| ਓ | ੋ | ਕੋ | Hōṛā | ō | [o] | like o in Spanish amor |

| ਔ | ੌ | ਕੌ | Kanōṛā | o | [ɔ] | like o in off |

Dotted circles represent the bearer consonant. Vowels are always pronounced after the consonant they are attached to. Thus, Sihari is always written to the left, but pronounced after the character on the right.

Vowel examples

| Word | IPA | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| ਆਲੂ | [ɑlu] | potato |

| ਦਿਲ | [d̪ɪl] | heart |

| ਗਾਂ | [gɑ̃] | cow |

Other signs

Nasalisation: tippi and bindi

Ṭippi ( ੰ ) and bindi ( ਂ ) are used for producing a nasal phoneme depending on the following obstruent or a nasal vowel at the end of a word. All short vowels use ṭippi and all long vowels are paired with bindi except for Dulankar ( ੂ ), which uses ṭippi instead. Older texts may follow other conventions.

Bindi ( ਂ ) is also used for nasalisation.

Gemination: addak

The use of addak ( ੱ ) indicates that the following consonant is geminate. This means that the subsequent consonant is doubled or reinforced.

Halant

The halant ( ੍ ) character is not used when writing Punjabi in Gurmukhī. However, it may occasionally be used in Sanskritised text or in dictionaries for extra phonetic information. When it is used, it represents the suppression of the inherent vowel.

The effect of this is shown below:

- ਕ – kə

- ਕ੍ – k

Visarg

The visarg symbol (ਃ U+0A03) is used very occasionally in Gurmukhī. It can either represent an abbreviation (like period is used in English) or it can act like a Sanskrit Visarga where a voiceless 'h' sound is pronounced after the vowel.

Udaat

The udaat symbol (ੑ U+0A51) occurs in older texts and indicates a high tone.

Numerals

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| Hindu–Arabic numeral system |

| East Asian |

| Alphabetic |

| Former |

| Positional systems by base |

| Non-standard positional numeral systems |

| List of numeral systems |

Gurmukhī has its own set of digits, used exactly as in other versions of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system. These are used extensively in older texts. In modern contexts, they have been replaced by standard Western Arabic numerals.

| Numeral | Name | Simple Transliteration | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| ੦ | ਸਿਫ਼ਰ [sɪfəɾ] | sifar | zero |

| ੧ | ਇੱਕ [ɪkː] | ikk | one |

| ੨ | ਦੋ [d̪oː] | do | two |

| ੩ | ਤਿੰਨ [t̪ɪnː] | tinn | three |

| ੪ | ਚਾਰ [tʃɑːɾ] | chār | four |

| ੫ | ਪੰਜ [pəndʒ] | punj | five |

| ੬ | ਛੇ [tʃʰeː] | che | six |

| ੭ | ਸੱਤ [sət̪ː] | satt | seven |

| ੮ | ਅੱਠ [əʈʰː] | aṭhṭh | eight |

| ੯ | ਨੌਂ [nɔ̃] | nauṃ | nine |

| ੧੦ | ਦਸ [d̪əs] | das | ten |

Unicode

Gurmukhī script was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 1991 with the release of version 1.0. Many sites still use proprietary fonts that convert Latin ASCII codes to Gurmukhī glyphs.

The Unicode block for Gurmukhī is U+0A00–U+0A7F:

| Gurmukhi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+0A0x | ਁ | ਂ | ਃ | ਅ | ਆ | ਇ | ਈ | ਉ | ਊ | ਏ | ||||||

| U+0A1x | ਐ | ਓ | ਔ | ਕ | ਖ | ਗ | ਘ | ਙ | ਚ | ਛ | ਜ | ਝ | ਞ | ਟ | ||

| U+0A2x | ਠ | ਡ | ਢ | ਣ | ਤ | ਥ | ਦ | ਧ | ਨ | ਪ | ਫ | ਬ | ਭ | ਮ | ਯ | |

| U+0A3x | ਰ | ਲ | ਲ਼ | ਵ | ਸ਼ | ਸ | ਹ | ਼ | ਾ | ਿ | ||||||

| U+0A4x | ੀ | ੁ | ੂ | ੇ | ੈ | ੋ | ੌ | ੍ | ||||||||

| U+0A5x | ੑ | ਖ਼ | ਗ਼ | ਜ਼ | ੜ | ਫ਼ | ||||||||||

| U+0A6x | ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ | ||||||

| U+0A7x | ੰ | ੱ | ੲ | ੳ | ੴ | ੵ | ੶ | |||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Digitisation of Gurmukhī manuscripts

Panjab Digital Library[9] has taken up digitisation of all available manuscripts of Gurmukhī Script. The script is just 500 years old, hence a lot of literature written in all these years is still traceable. Panjab Digital Library has digitised over 5 million pages from different manuscripts and most of them are available online.

Bibliography

- Following books/articles have been written on the origins of the Gurmukhī script (all in the Punjabi language):

- Gurbaksh (G.B.) Singh. Gurmukhi Lipi da Janam te Vikas. Chandigarh: Punjab University, 1950.

- Ishar Singh Tãgh, Dr. Gurmukhi Lipi da Vigyamulak Adhiyan. Patiala: Jodh Singh Karamjit Singh.

- Kala Singh Bedi, Dr. Lipi da Vikas. Patiala: Punjabi University, 1995.

- Kartar Singh Dakha. Gurmukhi te Hindi da Takra. 1948.

- Piara Singh Padam, Prof. Gurmukhi Lipi da Itihas. Patiala: Kalgidhar Kalam Foundation Kalam Mandir, 1953.

- Prem Parkash Singh, Dr. "Gurmukhi di Utpati." Khoj Patrika, Patiala: Punjabi University.

- Pritam Singh, Prof. "Gurmukhi Lipi." Khoj Patrika. p. 110, vol.36, 1992. Patiala: Punjabi University.

- Sohan Singh Galautra. Punjab dian Lipiã.

- Tarlochan Singh Bedi, Dr. Gurmukhi Lipi da Janam te Vikas. Patiala: Punjabi University, 1999.

See also

References

- ↑ SR Sharma (1992). Encyclopaedia of teaching languages in India, Volume 3. Anmol Publications. pp. 366–367.

- 1 2 Mandair, Arvind-Pal S.; Shackle, Christopher; Singh, Gurharpal (December 16, 2013). Sikh Religion, Culture and Ethnicity. Routledge. p. 13, Quote: "creation of a pothi in distinct Sikh script (Gurmukhi) seem to relate to the immediate religio-political context ...". ISBN 9781136846342. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

Mann, Gurinder Singh; Numrich, Paul; Williams, Raymond (2007). Buddhists, Hindus, and Sikhs in America. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 100, Quote: "He modified the existing writing systems of his time to create Gurmukhi, the script of the Sikhs; then ...". ISBN 9780198044246. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

Shani, Giorgio (March 2002). The Territorialization of Identity: Sikh Nationalism in the Diaspora. Japan: Kitakyushu University. p. 11. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

Harjeet Singh Gill (1996). Peter T. Daniels; William Bright, eds. The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7. - 1 2 3 4 Peter T. Daniels; William Bright (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Danesh Jain; George Cardona (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- ↑ Harnik Deol, Religion and Nationalism in India. Routledge, 2000.

ISBN 0-415-20108-X, 9780415201087. Page 22. "(...) the compositions in the Sikh holy book, Adi Granth, are a melange of various dialects, often coalesced under the generic title of Sant Bhasha."

The making of Sikh scripture by Gurinder Singh Mann. Published by Oxford University Press US, 2001. ISBN 0-19-513024-3, ISBN 978-0-19-513024-9 Page 5. "The language of the hymns recorded in the Adi Granth has been called Sant Bhasha, a kind of lingua franca used by the medieval saint-poets of northern India. But the broad range of contributors to the text produced a complex mix of regional dialects."

Surindar Singh Kohli, History of Punjabi Literature. Page 48. National Book, 1993. ISBN 81-7116-141-3, ISBN 978-81-7116-141-6. "When we go through the hymns and compositions of the Guru written in Sant Bhasha (saint-language), it appears that some Indian saint of 16th century...."

Nirmal Dass, Songs of the Saints from the Adi Granth. SUNY Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7914-4683-2, ISBN 978-0-7914-4683-6. Page 13. "Any attempt at translating songs from the Adi Granth certainly involves working not with one language, but several, along with dialectical differences. The languages used by the saints range from Sanskrit; regional Prakrits; western, eastern and southern Apabhramsa; and Sahiskriti. More particularly, we find sant bhasha, Marathi, Old Hindi, central and Lehndi Panjabi, Sgettland Persian. There are also many dialects deployed, such as Purbi Marwari, Bangru, Dakhni, Malwai, and Awadhi." - ↑ Danesh Jain; George Cardona (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 94–99, 72–73. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- ↑ George Cardona and Danesh Jain (2003), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415772945, pages 72-74

- 1 2 Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. xvii–xviii. ISBN 0-415-26604-1.

- ↑ Panjab Digital Library

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gurmukhi. |