Sexagesimal

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| Hindu–Arabic numeral system |

| East Asian |

| Alphabetic |

| Former |

| Positional systems by base |

| Non-standard positional numeral systems |

| List of numeral systems |

Sexagesimal (base 60) is a numeral system with sixty as its base. It originated with the ancient Sumerians in the 3rd millennium BC, was passed down to the ancient Babylonians, and is still used—in a modified form—for measuring time, angles, and geographic coordinates.

The number 60, a superior highly composite number, has twelve factors, namely 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30, and 60, of which 2, 3, and 5 are prime numbers. With so many factors, many fractions involving sexagesimal numbers are simplified. For example, one hour can be divided evenly into sections of 30 minutes, 20 minutes, 15 minutes, 12 minutes, 10 minutes, 6 minutes, 5 minutes, 4 minutes, 3 minutes, 2 minutes, and 1 minute. 60 is the smallest number that is divisible by every number from 1 to 6; that is, it is the lowest common multiple of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Origin

It is possible for people to count on their fingers to 12 using one hand only, with the thumb pointing to each finger bone on the four fingers in turn. A traditional counting system still in use in many regions of Asia works in this way, and could help to explain the occurrence of numeral systems based on 12 and 60 besides those based on 10, 20 and 5. In this system, one hand counts repeatedly to 12, displaying the number of iterations on the other, until five dozens, i. e. the 60, are full.[1][2]

According to Otto Neugebauer, the origins of sexagesimal are not as simple, consistent, or singular in time as they are often portrayed. Throughout their many centuries of use, which continues today for specialized topics such as time, angles, and astronomical coordinate systems, sexagesimal notations have always contained a strong undercurrent of decimal notation, such as in how sexagesimal digits are written. Their use has also always included (and continues to include) inconsistencies in where and how various bases are to represent numbers even within a single text.[3]

The most powerful driver for rigorous, fully self-consistent use of sexagesimal has always been its mathematical advantages for writing and calculating fractions. In ancient texts this shows up in the fact that sexagesimal is used most uniformly and consistently in mathematical tables of data.[3] Another practical factor that helped expand the use of sexagesimal in the past even if less consistently than in mathematical tables, was its decided advantages to merchants and buyers for making everyday financial transactions easier when they involved bargaining for and dividing up larger quantities of goods. The early shekel in particular was one-sixtieth of a mana,[3] though the Greeks later coerced this relationship into the more base-10 compatible ratio of a shekel being one-fiftieth of a mina.

Apart from mathematical tables, the inconsistencies in how numbers were represented within most texts extended all the way down to the most basic Cuneiform symbols used to represent numeric quantities.[3] For example, the Cuneiform symbol for 1 was an ellipse made by applying the rounded end of the stylus at an angle to the clay, while the sexagesimal symbol for 60 was a larger oval or "big 1". But within the same texts in which these symbols were used, the number 10 was represented as a circle made by applying the round end of the style perpendicular to the clay, and a larger circle or "big 10" was used to represent 100. Such multi-base numeric quantity symbols could be mixed with each other and with abbreviations, even within a single number. The details and even the magnitudes implied (since zero was not used consistently) were idiomatic to the particular time periods, cultures, and quantities or concepts being represented. While such context-dependent representations of numeric quantities are easy to critique in retrospect, in modern time we still have "dozens" of regularly used examples (some quite "gross") of topic-dependent base mixing, including the particularly ironic recent innovation of adding decimal fractions to sexagesimal astronomical coordinates.[3]

Usage

Babylonian mathematics

The sexagesimal system as used in ancient Mesopotamia was not a pure base-60 system, in the sense that it did not use 60 distinct symbols for its digits. Instead, the cuneiform digits used ten as a sub-base in the fashion of a sign-value notation: a sexagesimal digit was composed of a group of narrow, wedge-shaped marks representing units up to nine (Y, YY, YYY, YYYY, ..., YYYYYYYYY) and a group of wide, wedge-shaped marks representing up to five tens (<, <<, <<<, <<<<, <<<<<). The value of the digit was the sum of the values of its component parts:

Numbers larger than 59 were indicated by multiple symbol blocks of this form in place value notation.

Because there was no symbol for zero in Sumerian or early Babylonian numbering systems, it is not always immediately obvious how a number should be interpreted, and its true value must sometimes have been determined by its context. Without context, this system was fairly ambiguous. For example, the symbols for 1 and 60 are identical.[4][5] Later Babylonian texts used a placeholder (![]()

Other historical usages

In the Chinese calendar, a sexagenary cycle is commonly used, in which days or years are named by positions in a sequence of ten stems and in another sequence of 12 branches. The same stem and branch repeat every 60 steps through this cycle.

Book VIII of Plato's Republic involves an allegory of marriage centered on the number 604 = 12960000 and its divisors. This number has the particularly simple sexagesimal representation 1,0,0,0,0. Later scholars have invoked both Babylonian mathematics and music theory in an attempt to explain this passage.[6]

Ptolemy's Almagest, a treatise on mathematical astronomy written in the second century AD, uses base 60 to express the fractional parts of numbers. In particular, his table of chords, which was essentially the only extensive trigonometric table for more than a millennium, has fractional parts of a degree in base 60.

Medieval astronomers also used sexagesimal numbers to note time. Around 1235 John of Sacrobosco discussed the length of the tropical year using sexagesimal divisions of the hour, in what may be the earliest division of the hour into minutes and seconds.[7] The Parisian version of the Alfonsine tables (ca. 1320) used the day as the basic unit of time, recording multiples and fractions of a day in base 60 notation.[8]

The sexagesimal number system continued to be frequently used by European astronomers for performing calculations as late as 1671.[9] For instance, Jost Bürgi in Fundamentum Astronomiae (presented to Emperor Rudolf II in 1592), his colleague Ursus in Fundamentum Astronomicum, and possibly also Henry Briggs, used multiplication tables based on the sexagesimal system in the late 16th Century, to calculate sines.[10]

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century Tamil astronomers were found to make astronomical calculations, reckoning with shells using a mixture of decimal and sexagesimal notations developed by Hellenistic astronomers.[11]

Base-60 number systems have also been used in some other cultures that are unrelated to the Sumerians, for example by the Ekari people of Western New Guinea.[12][13]

Notation

In Hellenistic Greek astronomical texts, such as the writings of Ptolemy, sexagesimal numbers were written using the Greek alphabetic numerals, with each sexagesimal digit being treated as a distinct number. The Greeks limited their use of sexagesimal numbers to the fractional part of a number and employed a variety of markers to indicate a zero.[14]

In medieval Latin texts, sexagesimal numbers were written using Arabic numerals; the different levels of fractions were denoted minuta (i.e., fraction), minuta secunda, minuta tertia, etc. By the seventeenth century it became common to denote the integer part of sexagesimal numbers by a superscripted zero, and the various fractional parts by one or more accent marks. John Wallis, in his Mathesis universalis, generalized this notation to include higher multiples of 60; giving as an example the number 49‵‵‵‵,36‵‵‵,25‵‵,15‵,1°,15′,25′′,36′′′,49′′′′; where the numbers to the left are multiplied by higher powers of 60, the numbers to the right are divided by powers of 60, and the number marked with the superscripted zero is multiplied by 1.[15] This notation leads to the modern signs for degrees, minutes, and seconds. The same minute and second nomenclature is also used for units of time, and the modern notation for time with hours, minutes, and seconds written in decimal and separated from each other by colons may be interpreted as a form of sexagesimal notation.

In modern studies of ancient mathematics and astronomy it is customary to write sexagesimal numbers with each sexagesimal digit represented in standard decimal notation as a number from 0 to 59, and with each digit separated by a comma. When appropriate, the fractional part of the sexagesimal number is separated from the whole number part by a semicolon rather than a comma, although in many cases this distinction may not appear in the original historical document and must be taken as an interpretation of the text.[16] Using this notation the square root of two, which in decimal notation appears as 1.41421... appears in modern sexagesimal notation as 1;24,51,10....[17] This notation is used in this article.

Modern usage

Unlike most other numeral systems, sexagesimal is not used so much in modern times as a means for general computations, or in logic, but rather, it is used in measuring angles, geographic coordinates, electronic navigation, and time.

One hour of time is divided into 60 minutes, and one minute is divided into 60 seconds. Thus, a measurement of time such as 3:23:17 (three hours, 23 minutes, and 17 seconds) can be interpreted as a sexagesimal number, meaning 3 × 602 + 23 × 601 + 17 × 600 seconds. As with the ancient Babylonian sexagesimal system, however, each of the three sexagesimal digits in this number (3, 23, and 17) is written using the decimal system.

Similarly, the practical unit of angular measure is the degree, of which there are 360 (six sixties) in a circle. There are 60 minutes of arc in a degree, and 60 arcseconds in a minute.

In some usage systems, each position past the sexagesimal point was numbered, using Latin or French roots: prime or primus, seconde or secundus, tierce, quatre, quinte, etc. To this day we call the second-order part of an hour or of a degree a "second". Until at least the 18th century, 1/60 of a second was called a "tierce" or "third".[18][19]

YAML

In version 1.1[20] of the YAML data storage format, sexagesimals are supported for plain scalars, and formally specified both for integers[21] and floating point numbers[22]. This has led to confusion, as e.g. some MAC addresses would be recognised as sexagesimals and loaded as ingtegers, where others were not and loaded as strings. In YAML 1.2 support for sexagesimals was dropped[23].

Fractions

In the sexagesimal system, any fraction in which the denominator is a regular number (having only 2, 3, and 5 in its prime factorization) may be expressed exactly.[24] The table below shows the sexagesimal representation of all fractions of this type in which the denominator is less than 60. The sexagesimal values in this table may be interpreted as giving the number of minutes and seconds in a given fraction of an hour; for instance, 1/9 of an hour is 6 minutes and 40 seconds. However, the representation of these fractions as sexagesimal numbers does not depend on such an interpretation.

| Fraction: | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1/5 | 1/6 | 1/8 | 1/9 | 1/10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexagesimal: | 30 | 20 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 7,30 | 6,40 | 6 |

| Fraction: | 1/12 | 1/15 | 1/16 | 1/18 | 1/20 | 1/24 | 1/25 | 1/27 |

| Sexagesimal: | 5 | 4 | 3,45 | 3,20 | 3 | 2,30 | 2,24 | 2,13,20 |

| Fraction: | 1/30 | 1/32 | 1/36 | 1/40 | 1/45 | 1/48 | 1/50 | 1/54 |

| Sexagesimal: | 2 | 1,52,30 | 1,40 | 1,30 | 1,20 | 1,15 | 1,12 | 1,6,40 |

However numbers that are not regular form more complicated repeating fractions. For example:

- 1/7 = 0;8,34,17,8,34,17 ... (with the sequence of sexagesimal digits 8,34,17 repeating infinitely many times) = 0;8,34,17

- 1/11 = 0;5,27,16,21,49

- 1/13 = 0;4,36,55,23

- 1/14 = 0;4,17,8,34

- 1/17 = 0;3,31,45,52,56,28,14,7

- 1/19 = 0;3,9,28,25,15,47,22,6,18,56,50,31,34,44,12,37,53,41

The fact in arithmetic that the two numbers that are adjacent to sixty, namely 59 and 61, are both prime numbers implies that simple repeating fractions that repeat with a period of one or two sexagesimal digits can only have 59 or 61 as their denominators (1/59 = 0;1; 1/61 = 0;0,59), and that other non-regular primes have fractions that repeat with a longer period.

Examples

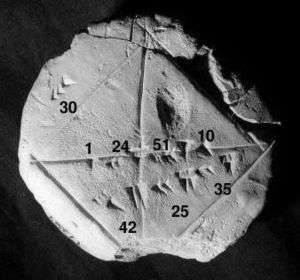

The square root of 2, the length of the diagonal of a unit square, was approximated by the Babylonians of the Old Babylonian Period (1900 BC – 1650 BC) as

Because √2 ≈ 1.41421356... is an irrational number, it cannot be expressed exactly in sexagesimal (or indeed any integer-base system), but its sexagesimal expansion does begin 1;24,51,10,7,46,6,4,44... (![]()

The length of the tropical year in Neo-Babylonian astronomy (see Hipparchus), 365.24579... days, can be expressed in sexagesimal as 6,5;14,44,51 (6 × 60 + 5 + 14/60 + 44/602 + 51/603) days. The average length of a year in the Gregorian calendar is exactly 6,5;14,33 in the same notation because the values 14 and 33 were the first two values for the tropical year from the Alfonsine tables, which were in sexagesimal notation.

The value of π as used by the Greek mathematician and scientist Claudius Ptolemaeus (Ptolemy) was 3;8,30 = 3 + 8/60 + 30/602 = 377/120 ≈ 3.141666....[26] Jamshīd al-Kāshī, a 15th-century Persian mathematician, calculated π in sexagesimal numbers to an accuracy of nine sexagesimal digits; his value for 2π was 6;16,59,28,1,34,51,46,14,50.[27][28] Like √2 above, 2π is an irrational number and cannot be expressed exactly in sexagesimal. Its sexagesimal expansion begins 6;16,59,28,1,34,51,46,14,49,55,12,35... (![]()

See also

References

- ↑ Ifrah, Georges (2000), The Universal History of Numbers: From prehistory to the invention of the computer., John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 0-471-39340-1 . Translated from the French by David Bellos, E.F. Harding, Sophie Wood and Ian Monk.

- ↑ Macey, Samuel L. (1989), The Dynamics of Progress: Time, Method, and Measure, Atlanta, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, p. 92, ISBN 978-0-8203-3796-8

- 1 2 3 4 5 Neugebauer, O. (1969), The Exact Sciences In Antiquity, Dover, pp. 17–19, ISBN 0-486-22332-9

- ↑ Bello, Ignacio; Britton, Jack R.; Kaul, Anton (2009), Topics in Contemporary Mathematics (9th ed.), Cengage Learning, p. 182, ISBN 9780538737791 .

- 1 2 Lamb, Evelyn (August 31, 2014), "Look, Ma, No Zero!", Scientific American, Roots of Unity

- ↑ Barton, George A. (1908), "On the Babylonian origin of Plato's nuptial number", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 29: 210–219, doi:10.2307/592627, JSTOR 592627 . McClain, Ernest G.; Plato, (1974), "Musical "Marriages" in Plato's "Republic"", Journal of Music Theory, 18 (2): 242–272, doi:10.2307/843638, JSTOR 843638

- ↑ Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (2018), Scandalous Error: Calendar Reform and Calendrical Astronomy in Medieval Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 126, ISBN 9780198799559,

Sacrobosco switched to sexagesimal fractions, but rendered them more congenial to computistical use by applying them not to the day but to the hour, thereby inaugurating the use of hours, minutes, and seconds that still prevails in the twenty-first century.

- ↑ Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (2018), Scandalous Error: Calendar Reform and Calendrical Astronomy in Medieval Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 196, ISBN 9780198799559,

One noteworthy feature of the Alfonsine Tables in their Latin-Parisian incarnation is the strict 'sexagesimalization' of all tabulated parameters, as … motions and time intervals were consistently dissolved into base-60 multiples and fractions of days or degrees.

- ↑ Newton, Isaac (1671), The Method of Fluxions and Infinite Series: With Its Application to the Geometry of Curve-lines., London: Henry Woodfall (published 1736), p. 146,

The most remarkable of these is the Sexagenary or Sexagesimal Scale of Arithmetick, of frequent use among Astronomers, which expresses all possible Numbers, Integers or Fractions, Rational or Surd, by the Powers of Sixty, and certain numeral Coefficients not exceeding fifty-nine.

- ↑ Folkerts, Menso; Launert, Dieter; Thom, Andreas (2016), "Jost Bürgi's method for calculating sines", Historia Mathematica, 43 (2): 133–147, arXiv:1510.03180, doi:10.1016/j.hm.2016.03.001, MR 3489006

- ↑ Neugebauer, Otto (1952), "Tamil Astronomy: A Study in the History of Astronomy in India", Osiris, 10: 252–276, doi:10.1086/368555 ; reprinted in Neugebauer, Otto (1983), Astronomy and History: Selected Essays, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90844-7

- ↑ Bowers, Nancy (1977), "Kapauku numeration: Reckoning, racism, scholarship, and Melanesian counting systems" (PDF), Journal of the Polynesian Society, 86 (1): 105–116., archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-05

- ↑ Lean, Glendon Angove (1992), Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania, Ph.D. thesis, Papua New Guinea University of Technology, archived from the original on 2007-09-05 . See especially chapter 4 Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Aaboe, Asger (1964), Episodes from the Early History of Mathematics, New Mathematical Library, 13, New York: Random House, pp. 103–104

- ↑ Cajori, Florian (2007) [1928], A History of Mathematical Notations, 1, New York: Cosimo, Inc., p. 216, ISBN 9781602066854

- ↑ Neugebauer, Otto; Sachs, Abraham Joseph; Götze, Albrecht (1945), Mathematical Cuneiform Texts, American Oriental Series, 29, New Haven: American Oriental Society and the American Schools of Oriental Research, p. 2

- ↑ Aaboe (1964), pp. 15–16, 25

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (1998), A natural history of vision, MIT Press, p. 193, ISBN 978-0-262-73129-4

- ↑ Lewis, Robert E. (1952), Middle English Dictionary, University of Michigan Press, p. 231, ISBN 978-0-472-01212-1

- ↑ http://yaml.org/spec/1.1/

- ↑ http://yaml.org/type/int.html

- ↑ http://yaml.org/type/float.html

- ↑ http://yaml.org/spec/1.2/spec.html#id2805071

- ↑ Neugebauer, Otto E. (1955), Astronomical Cuneiform Texts, London: Lund Humphries

- ↑ Fowler, David; Robson, Eleanor (1998), "Square root approximations in old Babylonian mathematics: YBC 7289 in context", Historia Mathematica, 25 (4): 366–378, doi:10.1006/hmat.1998.2209, MR 1662496

- ↑ Toomer, G. J., ed. (1984), Ptolemy's Almagest, New York: Springer Verlag, p. 302, ISBN 0-387-91220-7

- ↑ Youschkevitch, Adolf P., "Al-Kashi", in Rosenfeld, Boris A., Dictionary of Scientific Biography, p. 256 .

- ↑ Aaboe (1964), p. 125

Further reading

External links

- "Facts on the Calculation of Degrees and Minutes" is an Arabic language book by Sibṭ al-Māridīnī, Badr al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad (b. 1423). This work offers a very detailed treatment of sexagesimal mathematics and includes what appears to be the first mention of the periodicity of sexagesimal fractions.