History of the Punjab

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Punjab |

|

Prehistoric

|

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

Medieval

|

|

Colonial

|

|

Post-Independence

|

| History of Pakistan |

| Part of a series on the |

| Punjabis |

|---|

|

|

Asia

Europe North America |

|

Punjab portal |

The History of the Punjab concerns the history of the Punjab region the Northern area of the Indian Subcontinent that straddles the modern day countries of India and Pakistan. Historically known as Sapta Sindhu, or the Land of Seven Rivers, the name Punjab was given by later Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent. Ancient Punjab region was the primary geographical extent of the Indus Valley Civilisation, which was notable for advanced technologies and amenities that the people of the region had used. The region was historically a Hindu-Buddhist region, known for its high activity of scholarship, technology, and arts. Intermittent wars between various kingdoms was characteristic of this time, except in times of temporary unification under centralised Indian Empires or invading powers.

After the arrival of Islamic invaders, that had managed to rule throughout a long period of the region's history, much of Western Punjab had become a centre of Islamic culture in the Indian subcontinent. An interlude of Sikh rule under the Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his Sikh Empire had seen a brief resurfacing of traditional culture until the British had annexed the region into their larger British Empire. After the British had left, the region was partitioned into a Hindu-Sikh majority area that would go to the secular state of India, and a Muslim majority area that would go to the Islamic state of Pakistan to prevent conflict.

Vedic Era

Indus Valley Civilisation

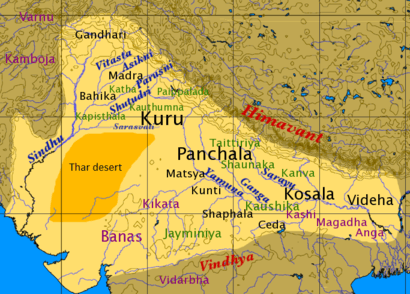

Punjab in ancient times was known as the Sapt-Sindhava, or land of the seven rivers. The name Punjab was given by later Islamic invaders. The aforementioned seven rivers were the Vitsta and Vitamasa (Jhelum), Asikni (Chenab), Parusni and Iravati (Ravi), Vipasa (Beas), and the Satudri (Sutlej).

It is believed by most scholars that the earliest trace of human habitation in India traces to the Soan valley between the Indus and the Jhelum rivers. This period goes back to the first inter-glacial period in the second Ice Age, from which remnants of stone and flint tools have been found.[1]

Punjab and the surrounding areas are the location of the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilisation, also known as the Harappan Civilisation. There are ruins of cities, thousands of years old, found in these areas with the most notable being those of Harappa, Rakhigarhi and Rupar. Besides the aforementioned sites, hundreds of ancient settlements have been found throughout the region, spanning an area of about 100 miles. These ancient towns and cities had advanced features such as city-planning, brick-built houses, sewage and draining systems, as well as public baths. The people of the Indus Valley also developed a writing system, that has to this day not been deciphered.[2]

Vedic descriptions

Literary evidence from the Vedic era suggests a transition from early small janas, or tribes, to many Janapadas (territorial civilisations) and gaṇa sangha societies. The latter are loosely translated to being oligarchies or republics. These political entities were represented from the Rig Veda to the Astadhyayi by Panini. Archaeologically, the time span of these entities corresponds to phases also present in the Indo-Gangetic divide and the upper Gangetic basin.[3]

Some of the early Janas of the Rig Veda can be strongly attributed to Punjab. Although their distribution patterns are not satisfactorily ascertainable, they are associated with the Porusni, Asikni, Satudri, Vipas, and Saraswati. The rivers of the Punjab often corresponded to the eastern Janapadas. Rig Vedic Janas such as the Druhyus, Anus, Purus, Yadus, Turvasas, Bharatas, and others were associated in Punjab and the Indo-Gangetic plain. Other Rig Vedic Janapadas such as the Pakhthas, Bhalanasas, Visanins, and Sivas were associated with areas in the north and west of the Punjab.[3]

An important event of the Rig Vedic era was the "Battle of Ten Kings" which was fought on the banks of the river Parusni (identified with the present-day Ravi river) between king Sudas of the Trtsu lineage of the Bharata clan on the one hand and a confederation of ten tribes on the other. The ten tribes pitted against Sudas comprised five major tribes: the Purus, the Druhyus, the Anus, the Turvasas and the Yadus; in addition to five minor ones: the Pakthas, the Alinas, the Bhalanas, the Visanins and the Sivas. Sudas was supported by the Vedic Rishi Vasishtha, while his former Purohita, the Rishi Viswamitra, sided with the confederation of ten tribes.[4] Sudas had earlier defeated Samvaran and ousted him from Hastinapur. It was only after the death of Sudas that Samvaran could return to his kingdom.[5]

A second battle, referred to as the Mahabharat in ancient texts, was fought in the Punjab on a battlefield known as Kurukshetra. This was fought between the Pandavas and the Kauravas. Duryodhana, a descendant of Kuru (who was the son of king Samvaran), had tried to insult the Panchali princess Draupadi in revenge for defeating his ancestor Samvaran.[5]

Many Janapadas were mentioned from Vedic texts and are confirmed by Ancient Greek historical sources. Most of the Janapadas that had exerted large territorial influence, or Mahajanapadas, had been raised in the Indo-Gangetic plain with the exception of Gandhara in modern-day Afghanistan. There was a large level of contact between all the Janapadas of ancient India with descriptions being given of trading caravans, movement of students from universities, and itineraries of princes.[6]

Pre-Islamic Punjab was also a centre of learning for Ancient India, and many ashrams and universities. The most notable of the universities is that at Taxila (also referred to as Takhsh-Shila), which was dedicated to the study of the "three Vedas and 18 branches of knowledge". In its heyday, it had attracted students from all over India as well as those from surrounding countries.[5]

Mauryan Era

Alexander's invasion

After overrunning the Achaemenid Empire, Alexander the Great turned his sights to India. This was the first time he moved beyond the limits of the Persian Empire. Alexander sent heralds ahead of him to the native rulers on the west side of the Indus and divided his army into two. He led one wing himself, and the other was commanded by Hephastion. Alexander took his troops and razed several cities, fought a battle at Massaka which turned into a massacre, and conducted the battle at Aornos rock. Somewhere in this region, Alexander visited a city called Nysa which was in legend founded by a god.[7] After crossing the Indus, Alexander was welcomed by the native ruler of Takshashila, known to the Greeks as Taxila, and other allies. Onesikritos was sent to interview the native ascetics about their way of life, but the conversation was rumoured to be difficult as the Greeks had to use three different levels of interpreters. Alexander was nevertheless impressed enough to bring an Indian philosopher whom the Greeks called Kalanos. Another Indian philosopher was asked also but had refused to come. When Alexander had reached Malloi and Oxydrakai in 325 B.C, the people had claimed that they always lived freely, directly contradicting with Persian accounts of rule over the region. After this, Alexander's first opponent was the Raja Porus. Porus and Taxiles were longtime enemies, and the latter saw Alexander's arrival as a way to settle old scores.[8]

Porus and Alexander had fought a battle on the Hydaspes, which was the last major battle of Alexander's campaign. The armies had met in June, when the monsoon had begun, and it was the first time Alexander and his troops had encountered Elephants in battle. After the defeat of Porus in Greek sources, most armies that he had encountered had come to submit, with very few refusing to do so such as the people of Sangala who were massacred.[9]Supposedly after the disheartened and homesick attitude of his troops, Alexander had returned home through Malois.[5] On his return, Alexander had conquered many resisting Indian janas and Janapadas, and those who had refused were killed. Many Brahmans were noted to be executed by Alexander, much to the shock of the Indians. Nevertheless, Alexander made little effort to retain the land he had conquered.[10]

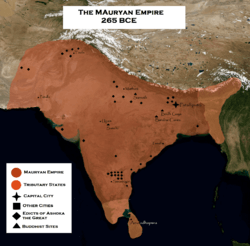

Maurya Empire

Chandragupta Maurya, with the aid of Kautilya, had established his empire around 320 B.C. The early life of Chandragupta Maurya is not clear. Kautilya enrolled the young Chandragupta in the university at Taxila to educate him in the arts, sciences, logic, mathematics, warfare, and administration. With the help of the small Janapadas of Punjab and Sindh, he had gone on to conquer much of the North West.[11] He then defeated the Nanda rulers in Pataliputra to capture the throne. Chandragupta Maurya fought Alexander's successor in the east, Seleucus when the latter invaded. In a peace treaty, Seleucus ceded all territories west of the Indus and offered a marriage, including a portion of Bactria, while Chandragupta granted Seleucus 500 elephants.[11]

Chandragupta's rule was very well organised. The Mauryans had an autocratic and centralised administration system, aided by a council of ministers, and also a well-established espionage system. Much of Chandragupta's success is attributed to Chanakya, the author of the Arthashastra. Much of the Mauryan rule had a strong bureaucracy that had regulated tax collection, trade and commerce, industrial activities, mining, statistics and data, maintenance of public places, and upkeep of temples.[11]

Mauryan rule was advanced for its time, and foreign accounts of Indian cities mention many temples, libraries, universities, gardens, and parks. A notable account was that of the Greek ambassador Megasthenes who had visited the Mauryan capital of Pataliputra.[11]

The assassination of the last Mauryan emperor by the general Pushyamitra did not end in the break up of Mauryan rule entirely. Some of the eastern provinces, such as that of Kalinga, were quick to assert independence. Punjab and much of the Indo-Gangetic plain were still under the hold of Pushyamitra's empire as well as under the subsequent smaller offshoots that had asserted its claim over the region.

Golden Age

Gupta Empire

The origins of the Gupta Empire are believed to be from local Rajas as only the father and grandfather of Chandra Gupta are mentioned in inscriptions. Chandra Gupta's reign was an unsettled one, but under his son, Samudra Gupta, the empire reached supremacy over India roughly similar to the proportions that the Maurya Empire had exercised before. Various records exist of Samudra Gupta's conquest, showing that nearly all of North India and a portion of Southern India had been under Gupta rule. The Empire was organised along the lines of provinces, frontier feudatories, and subordinate kings of vassal states that had sworn fealty to the Empire. In the case of Punjab, the local Janapadas were semi-independent but were expected to obey orders and pay homage to the empire. Samudra Gupta was regarded as a patron of the arts and humanities. Inscriptions give evidence to the Raja not only being a learned man, but one fond of the company of poets and writers; one type of coinage even shows him playing on the veena.

Samudra Gupta was succeeded by his son Rama Gupta in whose time the Scythians, known as the Sakas, had begun to be recognised as a threat. Rama Gupta had attempted to pay off the Sakas, but this had cost him his throne. Usurped by Chandra Gupta II, the new emperor had begun to consolidate the power of the empire where traces of disruption had presented himself. Chandra Gupta II had gone on to defeat the Sakas, earning him the name Sakari Chandra Gupta. By this time the Empire still ruled over much of North India, but the authority in the South seemed to lapse.

Although the main achievement for which Chandra Gupta II is known is the victory over invaders, he was described as devoted to the arts of peace. Chandra Gupta II was an ardent worshipper of Vishnu, and was a patron of the revival of Puranic Hinduism——a movement that had revived and redefined Hinduism——displacing much of Buddhist influence within the period of a century. Under the Gupta court at this time the arts, sciences, and literature had flourished.

The 200 years of Gupta rule are said to be the climax of Hindu Imperial tradition. From the context of literature, art, religion, science, commerce, and architecture, the period under Gupta rule had prospered. The Mauryan bureaucracy, already converted to caste, had functioned with impartial loyalty throughout the Empire and surrounding areas. The Empire was organised in similar lines to that of the Mauryan Empire, and had a system of viceroys, governors, administrators, and ministers. Seals of police chiefs, military suppliers, and chief justices give further insight into the administration of the Guptas. The empire was also known for its art and architecture, characterised by the reduction of the foreign influence of the Greeks and Kushans, and re-assertion of Hindu art. The Gupta period was also the classical age of Sanskrit literature. Much of the original ancient Hindu texts from before the Gupta Empire are lost, but the current iterations of Sanskrit works such as that of the Mahabharata and Bhagvad Gita are from the editions of this time. The complete re-writing of the Hindu texts raised the question of why the writers of the period would do this. A historian claims that this was due to the foreign influence that was present due to previous invaders, and a re-writing was required for the re-assertion of the original ideals. Another feature of the Gupta rule was the development of Indian science. The early development of the decimal system with respect to zero, the heliocentric model, accurate calculations of the duration of a day, reasons behind eclipses, and advances in the natural sciences were all achievements from this period. Major scholars from this time included Aryabhata and Varahamhira.

The White Huns, who initially were part of the predominantly Buddhist Hephthalite group, established themselves in Afghanistan by the first half of the 5th century, with their capital at Bamiyan. The Huns invaded the Gupta Empire under Kumara Gupta (r.415-455). Kumara Gupta had just earlier defeated several revolts from the Pushyamitras, a tribe of central India. After the death of Kumaragupta in 467, the Huns renewed their attacks and managed to invade border provinces around this time.[12] Kumara Gupta's son Skanda Gupta had managed to defeat further Hun invasions. Skanda Gupta managed to defeat the Huns in such a manner that they were fully routed; the consequences of the Gupta victory over the Huns were far-reaching, leading a historian to believe that this was likely the reason for the Hun invasions further West.

After the death of Skanda Gupta, the Empire suffered from various wars of succession. The last major Gupta King was Buddha Gupta; after him, the Empire had split into various branches across India. Nevertheless, by the sixth century, the Huns had established themselves and Toramana and his son Mihirakula, who has been described to be a Saivite Hindu, had ruled over the approximate areas of Punjab, Rajputana, and Kashmir. Several accounts, including those by Chinese pilgrims, make reference to the cruelty of the Huns. There had been several alliances throughout this time that had checked the advance of the Huns, but it was not until 533-534 that Raja Yashovarman of Mandasor firmly defeated them.[12]

Empire of Harsha

After the disintegration of the Gupta Empire, Northern India was ruled by several independent kingdoms which carried on the traditions of the Gupta Empire within their own territories. Harshavardhana, commonly called Harsha, was an Indian emperor who ruled northern India from 606 to 647 from his capital Kanauj. Harsha's grandfather was Adityavardhana, a feudatory ruler of Thanesvar in eastern Punjab. Under his son Prabhakarvardhana, the dynasty emerged as a major state which was constantly at odds with the Huns and the nearby rulers of Malwa. Harsha was his nephew, and sought to conquer all of the country; at the height of his power, his kingdom spanned the entirety of Northern India. Harsha was defeated by the south Indian Emperor Pulakeshin II of the Chalukya dynasty when Harsha tried to expand his Empire into southern peninsula of India.[13]

Islamic Invasions

Early Islamic Invasions

Arab armies had earlier tried to penetrate deep into South Asia but were defeated by the South Indian Emperor Vikramaditya II of the Chalukya dynasty, South Indian general Dantidurga of the Rashtrakuta dynasty in Gujarat, and by Nagabhata of the Pratihara Dynasty in Malwa in the early 8th century.[14][15] Despite repeated campaigns, in 698 and 700, Arabs also failed to occupy the Kandahar-Ghazni-Kabul route to the Khyber Pass. Two small Hindu states of Zabul and Kabul in southern Afghanistan stubbornly defended this strategic area between the river Sindh and Koh Hindu Kush.[16]

A Brahmin dynasty, more commonly known as the Hindu Shahis, was ruling from Kabul and later Waihind, another Brahmin dynasty ruled in Punjab. During this period a Turkic kingdom was established Ghazni and Sabuktagin ascended its throne in 977. The kingdom had rapidly conquered nearby kingdoms, and also conquered the Shahi capital of Kabul. Alarmed by the rapid expansion of the Ghaznavids, the Hindu Shahi kingdom twice attacked Sabuktagin but failed in his objective. Gradually, Sabuktagin conquered all Shahi territories in Afghanistan, north of the Khyber Pass. He died in 997 and was succeeded by his son Mahmud after a brief war of succession among the brothers. [17]

Bhima Deva Shahi was the fourth king of the Hindu Kabul Shahis. As a devout Brahmin, in his old age, he committed ritual suicide in his capital town of Waihind, located on the right side of river Sindh, fourteen miles above Attock.[18] As Bhimadeva had no male heir, Jayapala succeeded the Shahi throne, which had included areas spanning from Punjab to Kabul in Afghanistan. Jayapala was defeated at Peshawar by Mahmud of Ghazni and the Shahis lost all territory north of river Sindh.[19] Anandapala and Trilochanapala, his son and grandson respectively, resisted Mahmud for another quarter of a century but Punjab was finally annexed to the Sultanate of Ghazni, around 1021.[20] After the Muslim attacks, many Punjabi scholars of Sanskrit had fled to schools and universities in Benares and Kashmir, which were at the time unaffected by Islamic invasion. Al Biruni wrote: "Hindu sciences have fled far away from those parts of the country that have been conquered by us, and fled to places which our hand cannot yet reach, to Kashmir, to Benares, and other places." These places were later to face the same depredations.[21]

Delhi Sultanate

In the late 12th century, Muhammad of Ghori began a systematic invasion of India. Between 1175 and 1192, the Ghurid dynasty had occupied the cities of Uch, Multan, Peshawar, Lahore, and Delhi. In 1206, the Ghurid general Qutb-al-din Aybeg and his successor Iltutmish founded the first of the series of Delhi Sultanates. Each dynasty would be an alternation of various inner-Asian military lords and their clients, constantly vying for power. These sultanates would make Delhi a safe haven for Muslim Turks and Persians who would flee the eventual Mongol invasions.[22]

The Khalji dynasty was the second dynasty of the Delhi sultanates, ruling from 1290 to 1320. This dynasty was a short-lived one, and extended Islamic rule to Gujarat, Rajasthan, the Deccan, and parts of Southern India. The Khalji dynasty reworked the tax system in India. Previously, the ruler would assign village locals to collect a share of the peasant's produce, using it to pay the soldiers and administrators. In 1300, Ala-al-din Khalji demanded that peasants pay one half of their produce, abolished the authority of local chiefs, and deprived the local lords of their power.[23]

If the Delhi Sultanate, an offshoot of the Islamic conquest, was to rule over India, it was necessary for there to be the cultural and ideological integration of the people. This effort of integration and cohesion took time to develop. The first gesture to bring the people into Islam was to destroy major Hindu temples. This was done to loot riches and to signify the defeat of the Hindu rulers and their gods. Sometimes these destroyed temples were replaced by Mosques in order to show victory to both Hindus and rival Muslims. [24] Examples are the mosque of Quwwat-al-Islam which incorporated stones and iron pillars from Hindu structures, and the Qutb Minar, which highlighted the presence of Islam. The dynasties of the Delhi sultanates stressed allegiance to the Caliphate and supported the judicial authority of the Ulama.[24]

The Khalji dynasty was succeeded by the Tughluq dynasty, which had ruled from 1320 to 1413. Muhammad bin Tughluq was supported by Turkic warriors, and was the first to introduce non-Muslims into the administration, to participate in local festivals, and permit the construction of Hindu temples. To maintain his identity as a Muslim, the Muhammad bin Tughluq adhered to Islamic laws, swore allegiance to the caliph in Cairo, appointed Ulamas, and imposed the tax on non-Muslims. The Tughluq dynasty, however, disintegrated rapidly due to revolts by governors, resistance from locals, and the re-formation of independent Hindu kingdoms. [25] The rule of the Delhi sultanates around this time was based upon Iranian-Muslim tradition. According to Barani, a Tughluq administrator in around 1360, the ruler must "follow the teachings of the Prophet, enforce Islamic law, suppress rebellions, punish heretics, subordinate nonbelievers, and protect the weak against the strong". The Islamic values that were idealised by the Delhi sultanates were ones that brought men in accordance with God's command by cultivating moral values in the governing authorities. [25]

After the death of the last Tughluq ruler Nasir-ud-din Mahmud, the nobles are believed to have chosen Daulat Khan Lodi for the throne. In 1414, Lodi was defeated by Khizr Khan, the founder of the Sayyid dynasty of the Sultanate. Khizr Khan professor to rule as the viceroy of Timur and his successor Shah Rukh. Under the Sayyid dynasty, Punjab, Dipalpur, and parts of Sindh had come under the rule of the Sultanates.[26] During this time, various regions such as Bengal, Deccan, Malwa, and others had gained independence from the Sultanate. The rule of the Sayyid dynasty was characterised by frequent revolts by the Hindus of the various Punjabi doabs.[26] The rule of the Sayyids experienced another revolt under the rule of their general Bahlul Lodi, who had at first occupied much of Punjab, yet failed to capture Delhi. In his second attempt, Bahlul Lodi captured Delhi and founded the Lodi dynasty, the last of the Delhi sultanates. [27] The Lodi dynasty reached its peak under Bahlul's grandson Sikander Lodi. Various road and irrigation projects were taken under his rule, and the rule had patronised Persian culture. Despite this, there was still persecution of the local Hindu people as many temples, such as that of Mathura, were destroyed and had a system of widespread discrimination against Hindus.[28] The rule of the last Lodi emperor was a weak one, and was eclipsed by the arrival of Babur's army. [29]

Mughal Empire

In 1526, Babur, a Timurid descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan from the Fergana Valley (modern-day Uzbekistan) was ousted from his ancestral domain in Central Asia. Bābur turned to India and crossed the Khyber Pass.[30] From his base in Afghanistan, he was able to secure control of Punjab, and in 1526 he decisively defeated the forces of the Delhi sultan Ibrāhīm Lodī at the First Battle of Panipat. The next year, he defeated the Rajput confederacy under Rana Sanga of Mewar, and in 1529 defeated the remnants of the Delhi sultanates. At his death in 1530 the Mughal Empire encompassed almost all of Northern India.[31]

Bābur’s son Humāyūn (reigned 1530–40 and 1555–56) had lost territory to rebels, but Humāyūn’s son Akbar (reigned 1556–1605) defeated the Hindu king Hemu at the Second Battle of Panipat (1556) and reestablished Mughal rule. Akbar's son Jahangir had furthered the size of the Mughal Empire through conquest, yet left much of the state bankrupt as a result. Akbar's son Shah Jahan (reigned 1628–1658) was known for his monuments, including the Taj Mahal. Shah Jahan's son Aurangzeb was especially known for his religious intolerance and was known for his destruction of schools and temples which he saw as un-Islamic. In addition to the murder of a Sikh Guru, Aurangzeb had instilled heavy taxes on Hindus and Sikhs that had later led to an economic depression.[31][32][33][34][35][36]

During the reign of Muḥammad Shah (1719–48), the empire began to decline, accelerated by warfare and rivalries, and. After the death of Muḥammad Shah in 1748, the Marathas attacked and ruled almost all of northern India. Mughal rule was reduced to only a small area around Delhi, which passed under Maratha (1785) and the British (1803) control. The last Mughal, Bahādur Shah II (reigned 1837–57), was exiled to Burma by the British.[31]

Mughal conflicts with Sikhs

The Sikh religion began around the time of the conquest of Northern India by Babur Shah, the founder of the Mughal Empire. The later Muslim Emperor Jahangir, however, saw the Sikhs as a political threat. He ordered Guru Arjun Dev to be put to death after he had refused to change the passage about Islam in the Adi Granth. When the Guru refused, Jahangir ordered him to be put to death by torture.[37] Guru Arjan Dev's death led to the sixth Guru Guru Hargobind to declare sovereignty in the creation of the Akal Takht and the establishment of a fort to defend Amritsar. Jahangir then jailed Guru Hargobind at Gwalior, but released him after a number of years when he no longer felt threatened. The succeeding son of Jahangir, Shah Jahan, took offence at Guru Hargobind's declaration and after a series of assaults on Amritsar, forced the Sikhs to retreat to the Sivalik Hills.[38] The ninth Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, moved the Sikh community to Anandpur and travelled extensively to visit and preach in defiance of Aurangzeb, who attempted to install Ram Rai as new guru. Guru Tegh Bahadur aided Kashmiri Pandits in avoiding conversion to Islam and was arrested by Aurangzeb. When offered a choice between conversion to Islam and death, he chose to die rather than compromise his principles and was executed.[39] Guru Gobind Singh assumed the guruship in 1675 and established the Khalsa, a collective army of baptised Sikhs, on 30 March 1699. The establishment of the Khalsa united the Sikh community against various Mughal-backed claimants to the guruship.[40]

Banda Singh Bahadur (also known as Lachman Das, Lachman Dev and Madho Das), (1670–1716) met Guru Gobind Singh at Nanded and adopted the Sikh religion. A short time before his death, Guru Gobind Singh ordered him to conquer Punjab and gave him a letter that commanded all Sikhs to join him. After two years of gaining supporters, Banda Singh Bahadur initiated an agrarian uprising by breaking up the large estates of Zamindar families and distributing the land to the peasants.[41] During the rebellion, Banda Singh Bahadur made it a point to destroy the cities in which the Muslims had been cruel to the supporters of Guru Gobind Singh. He executed Wazir Khan in revenge for the deaths of Guru Gobind Singh's sons after the Sikh victory at Sirhind.[42] He ruled the territory between the Sutlej river and the Yamuna river, established a capital in the Himalayas at Lohgarh and struck coinage in the names of Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh.[41] In 1716, he was defeated by the Mughals at his fort at Gurdas Nangal. The captured Sikhs were beheaded, their heads stuffed with hay, mounted on spears and carried on a procession to Delhi en route to the Qutb Minar. Banda Singh was told to dismount, as the Muslims placed his child in his arms and bade him to kill it. The child was ripped open and fed to him, as the Muslims had dismembered his limbs after refusing to convert to Islam.[43][44]

Durranis and Marathas

In 1747, the Durrani kingdom was established by the Pakhtun general, Ahmad Shah Abdali, and included Balochistan, Peshawar, Daman, Multan, Sindh, and Punjab. The first time Ahmad Shah invaded Hindustan, the Mughal imperial army checked his advance successfully. Yet subsequent events led to a double alliance, one by marriage and another politically, between the Afghan King and the Mughal Emperor. The battle of Panipat was the effect of this political alliance. After the victory of Panipat, Ahmad Shah Durrani became the primary ruler over Northern India. The influence of Durrani monarch continued in Northern India up to his death.[45]

In 1757, the Sikhs were persistently ambushing guards to loot trains. In order to send a message, and prevent such occurrences from recurring, Ahmad Shah destroyed the Shri Harimandir Sahib and filled the Sarovar (Holy water pool) with cow carcasses.[46]

In 1758 the Maratha Empire's general Raghunathrao attacked and conquered Lahore and Attock driving out Timur Shah Durrani, the son and viceroy of Ahmad Shah Abdali, in the process. Lahore, Multan, Kashmir and other subahs on the eastern side of Attock were under Maratha rule. In Punjab and Kashmir, the Marathas were now major players.[47] In 1761, following the victory at the Third battle of Panipat between the Durrani and the Maratha Empire, Ahmad Shah Abdali captured remnants of the Maratha Empire in Punjab and Kashmir regions and had consolidated control over them.

In 1762, there were persistent conflicts with the Sikhs. Sikh holocaust of 1762 took place under the Muslim provincial government based at Lahore to wipe out the Sikhs, with 30,000 Sikhs being killed, an offensive that had begun with the Mughals, with the Sikh holocaust of 1746,[48] and lasted several decades under its Muslim successor states.[49] The rebuilt Harminder Sahib was destroyed, and the pool was filled with cow entrails, again.[50][51]

Sikh Rule

In 1799, a process to unify Punjab was started by Ranjit Singh. Training his army under the style of the East India Company, it was able to conquer much of the Punjab and surrounding areas. The use of the suzerain-vassal polity as established by previous rulers had been instrumental in establishing the political control of the Sikhs. During this time, there was an increase in the population of Sikhs as well. In towns and cities, there was an increase in the population of urban Sikhs, while the same happened with an increase in rural Sikhs. This had also likely led to some of the ideological differences between Sikhs around this time.[52]

The invasions of the Muslim Zaman Shah, the second successor of Ahmad Shah Abdali had served as a catalyst. After the first invasion, Singh had recovered his own fort at Rohtas. During the second invasion, he had emerged as a leading Sikh chief. After the third invasion, he had decisively defeated Zamah Shah. This had eventually led to the takeover of Lahore in 1799. In 1809, Singh signed the Treaty of Amritsar with the British; in this treaty, Singh was recognised as the sole ruler of Punjab by the British and was given freedom to fight against the Muslims of surrounding areas.[53]

Within ten years of Ranjit Singh's death in 1839, the Empire was taken over by the British who had already more or less exerted indirect or direct influence throughout the Subcontinent. At Lahore, there were increasing levels of nobles vying for power. A growing instability, allowed the British to come in and take over control of the area. After the British victories at the battles of the Sutlej in 1845–46, the army and territory of the boy Raja Duleep Singh was cut down. Lahore was garrisoned by British troops, and given a resident in the Durbar. In 1849, the British had formally taken control.[52]

British Raj

The Punjab ruled under the British was larger than that under Ranjit Singh. The colonial rule of Punjab had instated a system of bureaucracy and measure of the law. Replacing the 'paternal' system of the ruling was replaced by 'machine rule' with a system of laws, codes, and procedures. For purposes of control, the British established new forms of communication and transportation. These included post systems, railways, roads, and telegraphs. Irrigation projects between 1860 and 1920 brought 10 million acres of land under cultivation. Despite these developments, colonial rule was marked by exploitation of resources. For the purpose of exports, the majority of external trade was controlled by British export banks. The Imperial government exercised control over the finances of the Punjab and took the majority of the income for itself.[54]

To the agrarian and commercial class was added a professional middle class that had risen the social ladder through the use of the English education, which opened up new professions in law, government, and medicine.[55]

By the 1870s there had been communities of Muslims of the Wahabi sect, drawn from the lower classes, that intended to use jihad to get rid of the non-Muslims by force. A highlight of religious controversy during this time was that of the Ahmaddiya movement. Mirza Gulam Ahmad in his Burahin-i-Ahmaddiya which was meant to rejuvenate Islam on the basis of the Quran, had attempted to refute both Christian missionaries, and Hindus and Sikhs. In another work, Ahmad argued that Guru Nanak was a Muslim. He interpreted Jihad as a peaceful method, and declared himself to be the Messiah. This was met with significant controversy.[56] In the first and second decades of the early 20th century, the idea of Hindu and Muslim separation had become an active political tone. Muslims were told to remain aloof of the Indian National Congress, the main body seeking Indian Independence, because there was a general fear that representation based on elections and employment based upon competition was not in their interest. The All India Muslim League's demand for separate electorates for Muslims was granted at Amritsar in 1909. The Muslim league also demanded separate electorates in every province, even in those without Muslim majority populations, which was also granted by the Indian National Congress in 1916.[57]

An important event of the British Raj in Punjab was the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre of 1919. The British brigadier-general R.E.H Dyer marched fifty riflemen of the 1/9th Gurkhas, 54th Sikhs, and 59th Sikhs into the Bagh and ordered them to open fire into the crowd that had collected there. The official number of deaths given by the British was given as 379 people dead, but there are reported to be greater than 1000 killed.[58] There had been many Indian Independence movements in Punjab at the time as well. Notably, the actions of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru on 17 December, 1928 in which the trio was responsible for killing J.P Saunders in revenge for the latter's murder of Lala Lajpati Rai. They were also responsible for the bombing of the Legislative Assembly in Delhi on the 8th of April in 1929. The three believed that the nonviolent movement was a failure. Nevertheless, the use of violence in the Indian Independence movement became unpopular after the execution of the trio on the 23 March 1932.[59]

Modern-day Punjab

In 1947, the Punjab Province of British India was divided along religious lines into West Punjab and East Punjab. The western part was assimilated into the new country of Pakistan while the east stayed in India. This led to riots. The Partition of India in 1947 split the former Raj province of Punjab; the mostly Muslim western part became the Pakistani province of West Punjab and the mostly Sikh and Hindu eastern part became the Indian province of Punjab. Many Sikhs and Hindus lived in the west, and many Muslims lived in the east, and so partition saw many people displaced and much intercommunal violence. Several small Punjabi princely states, including Patiala, also became part of India. The undivided Punjab, of which Punjab (Pakistan) forms a major region today, was home to a large minority population of Punjabi Sikhs and Hindus unto 1947 apart from the Muslim majority.[60]

Starting from the 1970s, some Sikhs called for the creation of a state known as Khalistan, along with the lines of Pakistan. According to Indian Government this lead to the state of emergency given by Indira Gandhi, who had called in Indian troops to stop the militants who were holding the Golden Temple hostage.[61] Miltant attacks targeted members of the Sikh majority that opposed the creation of Khalistan and wished to stay with India. The extremists were accused of carring out various attacks, including placing a bomb in an Air India flight over the Atlantic Ocean, killing more than 300 people. Other militant attacks had continued, notably against the Punjab police and others, in which alot of people were killed,Much of the funding for the groups had come from expatriate sources abroad in America and Europe, [62]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Singh 1989, p. 1.

- ↑ Singh 1989, pp. 2—3.

- 1 2 Chattopadhyaya 2003, p. 55.

- ↑ Frawley 2000, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 Singh 1989, p. 4.

- ↑ Chattopadhyaya 2003, pp. 56—57.

- ↑ Romm 2012, p. 375.

- ↑ Romm 2012, p. 376.

- ↑ Romm 2012, p. 377.

- ↑ Romm 2012, pp. 375—377.

- 1 2 3 4 Thorpe & Thorpe 2009, p. 33.

- 1 2 Daniélou 2003, pp. Ch.10.

- ↑ Majumdar 1977, p. 274.

- ↑ Jayapalan 2001, p. 152.

- ↑ Mani 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ Wink 2002, pp. 121—123.

- ↑ Digby 1976, p. 453.

- ↑ Mohan 2010, pp. 170—172.

- ↑ Barua 2006, p. 25.

- ↑ Mohan 2010, pp. 120—153.

- ↑ Scharfe 2002, p. 178.

- ↑ Lapidus 2014, p. 391.

- ↑ Lapidus 2014, pp. 391—392.

- 1 2 Lapidus 2014, p. 393.

- 1 2 Lapidus 2014, p. 394.

- 1 2 Jayapalan 2001, p. 53.

- ↑ Jayapalan 2001, p. 54.

- ↑ Jayapalan 2001, p. 56.

- ↑ Jayapalan 2001, p. 57.

- ↑ The Islamic World to 1600: Rise of the Great Islamic Empires (The Mughal Empire) Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "Mughal Dynasty". Encylcopaedia Britannica. Britannica. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Seiple 2013, p. 96.

- ↑ "Religions - Sikhism: Guru Tegh Bahadur". BBC. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ Singh & Fenech 2016, pp. 236—238.

- ↑ Fenech 2001, pp. 20—31, 623-642.

- ↑ McLeod 1999, pp. 155—165.

- ↑ Melton 2014, p. 1163.

- ↑ Jestice 2004, pp. 345—346.

- ↑ Johar 1975, pp. 192—210.

- ↑ Jestice 2004, pp. 312—313.

- 1 2 Singh 2008, pp. 25—26.

- ↑ Nesbitt 2016, p. 61.

- ↑ Bhaṅgū, Singh & Singh 2006, p. 415.

- ↑ Dhanoa 2005, p. 89.

- ↑ Potdar, Datto Vaman (1938). All India Modern History Congress.

- ↑ Singh 1984, p. 144-145.

- ↑ Roy, Kaushik. India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Permanent Black, India. pp. 80–1. ISBN 978-81-7824-109-8.

- ↑ A Popular Dictionary of Sikhism: Sikh Religion and Philosophy, p.86, Routledge, W. Owen Cole, Piara Singh Sambhi, 2005

- ↑ Khushwant Singh, A History of the Sikhs, Volume I: 1469–1839, Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1978, pp. 127–129

- ↑ Bhatia, Sardar Singh (1998). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Volume IV. Punjabi University. p. 396.

- ↑ Latif, Syad Muhammad (1964). The History of Punjab from the Remotest Antiquity to the Present Time. Eurasia Publishing House (Pvt.) Ltd. p. 283.

- 1 2 Grewal 1990, p. 99.

- ↑ Grewal 1990, pp. 100—101.

- ↑ Grewal 1990, pp. 128—129.

- ↑ Grewal 1990, p. 131.

- ↑ Grewal 1990, p. 134.

- ↑ Grewal 1990, p. 136.

- ↑ Narain, Savita. The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. Lancer Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-935501-87-9.

- ↑ Grewal 1990, p. 165.

- ↑ The Punjab in 1920s – A Case study of Muslims, Zarina Salamat, Royal Book Company, Karachi, 1997. table 45, pp. 136. ISBN 969-407-230-1

- ↑ Martin, Gus (2013). Understanding Terrorism: Challenges, Perspectives, and Issues. Sage. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-4522-0582-3.

- ↑ Lutz, James; Lutz, Brenda. Global Terrorism. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-415-53785-8.

Sources

Books

- Barua, Pradeep (2006), The State at War in South Asia, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-2785-9

- Bhaṅgū, R.S.; Singh, K.; Singh, K. (2006). Sri Gur Panth Prakash: Episodes 1 to 81. Sri Gur Panth Prakash. Institute of Sikh Studies. ISBN 978-81-85815-28-2.

- Chattopadhyaya, Brajadulal (2003), Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts, and Historical Issues, Permanent Black Publishers, ISBN 81-7824-143-9

- Daniélou, Alain (2003), A Brief History of India, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-0-89281-923-2

- Dhanoa, S.S. (2005). Raj Karega Khalsa (in Estonian). Sanbun Publishers.

- Frawley, David (2000), Gods, Sages and Kings: Vedic Secrets of Ancient Civilization, Vedic Secrets of Ancient Civil, Lotus Press, ISBN 978-0-910261-37-1

- Grewal, J. S. (1990), The Sikhs of the Punjab, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-2688-4-2

- Jayapalan, N. (2001), History of India, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (P) Limited, ISBN 978-81-7156-928-1

- Jestice, Phyllis (2004), Holy people of the world : a cross-cultural encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-355-1, OCLC 57407318

- Johar, S.S. (1975). Guru Tegh Bahadur: A Biography. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-030-3.

- Lapidus, I. M. (2014), A History of Islamic Societies, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-99150-6

- Majumdar, R. C. (1977), Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4

- Mani, C. M. (2005), A Journey Through India's Past, Northern Book Centre, ISBN 978-81-7211-194-6

- McLeod, Hew (1999), "Sikhs and Muslims in the Punjab", South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 22 (sup001): 155–165, doi:10.1080/00856408708723379, ISSN 0085-6401

- Melton, J. G. (2014), Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-61069-026-3

- Mohan, R. T. (2010), Afghanistan Revisited: The Brahmana Hindu Shahis of Afghanistan and the Punjab ( C.840.-1026 CE), MLBD

- Nesbitt, E. (2016). Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. Very short introductions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0.

- Romm, James S. (2012), The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander, Anchor Books, ISBN 978-1-4000-7967-4

- Scharfe, H. (2002), Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-12556-8

- Seiple, Chris (2013), The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Security, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-66744-9, OCLC 781277896

- Singh, Khushwant (1984). A history of the Sikhs. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-562643-8. OCLC 11819068.

- Singh, Ganda (1989), "History and Culture of Panjab Through The Ages", in Singh, Mohinder, History and Culture of Panjab, Atlantic Publishers, pp. 1–16, ISBN 978-8171560783

- Singh, H. (2008). Game of Love. Akaal Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9554587-1-2.

- Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E., eds. (2016), The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8, OCLC 874522334

- Thorpe, Showick; Thorpe, Edgar (2009), The Pearson General Studies Manual 2009, Pearson, ISBN 978-81-317-2133-9

- Wink, Andre (2002), Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7Th-11th Centuries, Brill, ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8

Journals

- Digby, Simon (1976). "Mohammad Habib: Politics and society during the early medieval period. Collected works, Vol. 1. Edited by K. A. Nizami. xx, 451 pp., front. New Delhi: People's Publishing House [for the] Centre of Advanced Study, Dept. of History, Aligarh Muslim University, 1974. Rs. 50". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 39 (02): 453. doi:10.1017/s0041977x0005028x. ISSN 0041-977X.

- Fenech, Louis E. (2001), "Martyrdom and the Execution of Guru Arjan in Early Sikh Sources", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 121 (1): 20, doi:10.2307/606726, ISSN 0003-0279

Further reading

- R. M. Chopra, "The Legacy of the Punjab", (1997), Punjabee Bradree, Calcutta.