Erlangen

| Erlangen | ||

|---|---|---|

View over Erlangen, 2012 | ||

| ||

Erlangen | ||

| Coordinates: 49°35′N 11°1′E / 49.583°N 11.017°ECoordinates: 49°35′N 11°1′E / 49.583°N 11.017°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Bavaria | |

| Admin. region | Mittelfranken | |

| District | Urban district | |

| Government | ||

| • Lord Mayor | Florian Janik (SPD) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 76.95 km2 (29.71 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 279 m (915 ft) | |

| Population (2017-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 110,998 | |

| • Density | 1,400/km2 (3,700/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 91052, 91054, 91056, 91058 | |

| Dialling codes |

09131, 0911 (OT Hüttendorf), 09132 (OT Neuses), 09135 (OT Dechsendorf) | |

| Vehicle registration | ER | |

| Website | www.erlangen.de | |

Erlangen (German pronunciation: [ˌɛɐ̯ˈlaŋən] (![]()

Erlangen is dominated by the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and the numerous branch offices of Siemens AG, as well as a large research Institute of the Fraunhofer Society and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light. An event that left its mark on the city was the settlement of Huguenots after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

Felix Klein's Erlangen program of 1872, considering the future of research in mathematics, is so called because Klein then taught at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg.

Geography

Erlangen is located on the edge of the Middle Franconian Basin[2] and at the floodplain of the Regnitz river.[3] The river divides the city into two halfs of approximately equal sizes. In the western part of the city the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal lies parallel to the Regnitz.

Neighboring municipalities

The following municipalities or non-municipal areas are adjacent to the city of Erlangen. They are listed clockwise, starting in the north:

The unincorporated area Mark, the municipalities Möhrendorf, Bubenreuth, Marloffstein, Spardorf and Buckenhof and the forest area Buckenhofer Forst (all belonging to the district of Erlangen-Höchstadt), the independent cities of Nuremberg and Fürth, the municipality Obermichelbach (district of Fürth), the city of Herzogenaurach and the municipality Hessdorf (both in the district of Erlangen-Höchstadt).

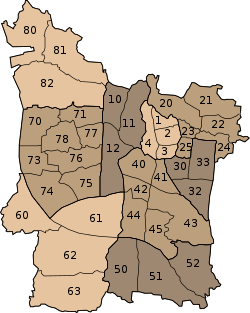

City arrangement

Erlangen officially consists of nine districts and 40 statistical districts, 39 of which are inhabited.[4] In addition, the urban area is subdivided into twelve land registry and land law relevant districts whose boundaries deviate largely from those of the statistical districts. The districts and statistical districts are partly formerly independent municipalities,[5][6] but also include newer settlements which names have also been coined as district names. The traditional and subjectively perceived boundaries of neighborhoods often deviate from the official ones.

Districts and statistical districts

|

|

|

Gemarkungen

Erlangen is divided into the following Gemarkungen:

|

|

|

Historical city districts

Some still common names of historical districts were not taken into account with the official designations. Examples are:

- Brucker Werksiedlung (in Gemarkung Bruck)

- Erba-Siedlung (in Gemarkung Bruck, am Anger)

- Essenbach (near Burgberg, north of Schwabach)

- Heusteg (in Gemarkung Großdechsendorf)

- Königsmühle (in Gemarkung Eltersdorf)

- Paprika-Siedlung (in Gemarkung Frauenaurach)

- Schallershof (in Gemarkung Frauenaurach)

- Siedlung Sonnenblick (in Gemarkung Büchenbach)

- Stadtrandsiedlung (in Gemarkung Büchenbach)

- St. Johann (in the statistical district Alterlangen)

- Werker (near Burgberg, east of the Regnitz)

- Zollhaus (eastern city center)

Climate

Erlangen is located in a transition zone from maritime to continental climate: the city is relatively low in precipitation (650mm per year), as usual in continental climate, but relatively warm with an annual mean temperature of 8.5 °C. The castle mountain in particular protects the area of the core city from cold polar air. In contrast, the Regnitzgrund is the cause of frequent fog.[7]

History

Overall history

Early history

In the prehistory of Bavaria, the Regnitz valley already played an important role as a passageway from north to south. In Spardorf a blade scraper was found in loess deposits, which could be attributed to the Gravettians, which places it at an age of about 25,000 years.[8] Due to the relatively barren soils in the area farming and settlements could only be detected at the end of the Neolithic (2800-2200 BC).[8] The "Erlanger Zeichensteine" (Erlangen Sign Stones, sandstone plates with petroglyphs) in the Mark-Forst north of the city also originated in this time period.[9] The stone plates were later resused as grave borders in the Urnfield period (1200-800 BC).[10]

Once investigated in 1913, it was found that the burial mound in Kosbach contained finds from the urnfield time as well as from the Hallstatt and La Tène period.[11] Next to the hill, the so-called "Kosbacher Altar", which was originated in the late Hallstatt period (about 500 BC),[12] was constructed. The altar is unique in this form and consists of a square stone setting with four upright, figural pillars at the corners and in the middle. The reconstruction of the site can be visited in the area, the middle guard is exhibited in the Erlangen city museum.[13][14]

Later history

Erlangen is first mentioned by name in a document from 1002. The origin of the name Erlangen is not clear. Attempts of local research to derive the name of alder (tree species) and anger (meadow ground), do not meet toponymical standards.[15]

As early as 976, Emperor Otto II had donated the church of St. Martin in Forchheim with accessories to the diocese of Würzburg.[16] Emperor Henry II confirmed this donation in 1002 and authorized its transfer from the bishopric to the newly founded Haug Abbey.[17] In contrast to the certificate of Otto II, the accessories, which also included the "villa erlangon" located in Radenzgau, were described in more detail here. At that time the Bavarian Nordgau extended to the Regnitz in the west and to the Schwabach in the north. Villa Erlangon must therefore have been located outside of these borders and thus not in the area of today's Erlangen Altstadt. However, as the name Erlangen is unique to today's town in Germany, the certificate could have only referred to it. The document also provides an additional piece of evidence: In 1002, Henry II bestowed further areas west of the Regnitz, including one mile from the Schwabach estuary to the east, one mile from this mouth upstream and downstream. These two squares are described in the document only by their lengths and the two river names. No reference to a specific place is given. They are also unrelated to the accessories of St. Martin, which included the villa erlangon, another reason why it must have been physically separated from the area of the two miles. Size and extent of the two squares correspong approximately to the area requirement of a village at the time, which supports the assumption that at the time of certification a settlement was under construction, which should be legitimized by this donation and later, as in similar cases, has adopted th name of the original settlement.[15] The new settlement was built in a triangle, today bordered by the streets Hauptstraße, Schulstraßeand Lazarettstraße, on a flooding-free sand dune.

Only 15 years later, in 1017, Henry II confirmed an exchange agreement, through which St. Martin and its accessories (including Erlangen) were given to the newly founded Bishopric of Bamberg, where it remained until 1361. During these centuries, the place name appears only sporadically.[18]

On 20 August 1063, Emperor Henry IV created two documents "actum Erlangen" while on a campaign. Local researchers therefore concluded that Erlangen must have already gained so much in extent that in 1063, Henry IV took his residence there with many princes and bishops[19] and was therefore the seat of a King's Court. It was even believed that this court could have been located in the Bayreuther Straße 8 and given away without mention by the certificate of 1002. Other evidence of this estate is also missing.[15] It is regarded as most likely today, that Henry IV was not residing in the "new" Erlangen, but rather in the older villa erlangon, as the north-south valley road changed to the left river bank of the Regnitz and then ran in the direction of Alterlangen, Kleinseebach-Baiersdorf to the north, to avoid the heights of the Erlangen Burgberg.[20]

Otherwise, Erlangen was usually only mentioned if the bishop pledged it due to lack of money. How exactly the village developed is unknown. Only the designation "grozzenerlang" in a bishop's urbarium from 1348 may be an indication that the episcopal village had outstripped the original villa erlangon.[20]

In December 1361, Emperor Charles IV bought "the village Erlangen including all rights, benefits and belongings".[19] and incorporated it into the area designated as New Bohemia, which was a fief of the Kingdom of Bohemia. Under the crown of Bohemia, the village developed rapidly. In 1367 the emperor spent three days in Erlangen and gave the "citizen and people of Erlangen" grazing rights in the imperial forest.[15] In 1374, Charles IV granted the inhabitants of Erlangen seven years of tax exemption. The money should instead be used to "improve" the village.[15] At the same time he lent the market right to Erlangen. Probably soon after 1361, the new ruler of the administration of the acquired property west of the town built the Veste Erlangen, on which a bailiff resided. King Wenceslaus built a mint and oficially granted township to Erlangen in 1398. He also gave the usual town privileges: Collection of tolls, construction of a department store with bread and meat bank and the construction of a defensive wall.[19]

Two years later, in 1400, the prince-electors unelected. He sold his Frankish possessions, including Erlangen, to his brother-in-law, the Nuremberg burgrave Johann III due to lack of funds in 1402. During the process of division of the burggrave property in Franconia, Erlangen was added to the Upper Principality, the future Principality of Bayreuth. The Erlangen coining facility ceased its operation because the Münzmeister was executed for counterfeiting in Nuremberg.[21]

During the Hussite Wars the town was completely destroyed for the first time in 1431.[15] The declaration of war by Margrave Albrecht Achilles to the city of Nuremberg in 1449 lead to the First Margrave War. However, as the army of Albrecht could not completely enclose the city, Nuremberg troops broke out again and devastated the Margravial towns and villages. As reported by a Nuremberg chronicler, they "burnt the market at most in Erlangen and brought a huge robbery". As soon as the town had recovered, Louis IX, Duke of Bavaria attacked the Margrave in 1459. Erlangen was raided and plundered again, this time by Bavarian troops. In the following years the town recovered again. Erlangen was spared from the Peasants' War in 1525 and the introduction of the Reformation in 1528 was peaceful. However, when Margrave Albert Alcibiades triggered the Second Margrave War, Erlangen was attacked again by the Nurembergers and partially destroyed. It was even considered to completely abandon the town. Because Emperor Charles V imposed the imperial ban on Albrecht, the Nurembergers incorporated Erlangen into their own territory. Albrecht died in January 1557. His successor, George Frederick, requested that the imperial sequestation over the Principality of Kulmbach be reversed and was able to take back the government one month later. Under his rule, the town recovered from the war damage and remained unharmed until well into the Thirty Years' War.[21]

During the four year Napoleonic occupation, Erlangen was the capital of the so-called "Low County" (Unterland) of the principality, encompassing the area until Neustadt an der Aisch and separated from the "High County" (Oberland) by a land corridor. In 1810 it became part of the Kingdom of Bavaria, together with the rest of former Brandenburg-Bayreuth.

While it was still part of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, the first French Huguenot refugees arrived in Erlangen in 1686. Margrave Christian Ernst of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, built a "new town" (Neustadt) for them. In 1706, the old town (just below the site of the annual Bergkirchweih) was almost completely destroyed by a fire, but soon rebuilt. In 1812, the old and new towns were merged into one.

In 1742, Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, founded a university for his royal seat of Bayreuth, but due to the rebelliousness of the local students, the university was transferred to Erlangen. Only later did it obtain the name of "Friedrich-Alexander-University" and become a Prussian state university. Famous students of these times were Johann Ludwig Tieck and Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder and Emmy Noether.

Already during the Bavarian municipal reform of 1818, the city was endowed with its own administration. In 1862, the canton administration Erlangen was founded, from which later arose the administrative district of Erlangen. In 1972, this district was merged with the administrative district of Höchstadt. Erlangen became the capital of this newly founded district Erlangen-Höchstadt. During this municipal reform, Erlangen was effectively enlarged considerably, thus in 1974 it had more than 100,000 inhabitants.

Points of interest

- The University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität) was founded in 1742 by Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, in the city of Bayreuth, but was relocated to Erlangen the next year. Today, it features five faculties; some departments (Economics and Education) are located in Nuremberg. About 39,000 students study at this university, of which about 20,000 are located in Erlangen.

- The Botanischer Garten Erlangen is a botanical garden maintained by the university.

Bergkirchweih

The Bergkirchweih is an annual beer festival, similar to the Oktoberfest in Munich but smaller in scale. It takes place during the twelve days before and after Pentecost (that is, 49 days after Easter); this period is called the "fifth season" by the locals. The beer is served at wooden tables in one-litre stoneware jugs under the trees of the "Berg", a small, craggy, and wooded hill with old caves (beer cellars) owned by local breweries. The cellars extend for 21 km (14 miles)[22] throughout the hill (the "Berg") and maintain a constant cool underground temperature. Until Carl von Linde invented the electric refrigerator in 1871, this was considered to be the largest refrigerator in Southern Germany.[23]

The beer festival draws more than one million visitors annually. It features carnival rides of high tech quality, food stalls of most Franconian dishes, including bratwurst, suckling pig, roasted almonds, and giant pretzels.

It is commonly known by local residents as the "Berchkärwa" (pronounced "bairch'-care-va") or simply the "Berch", like in "Gehma auf'n Berch!" ("Let's go up the mountain!").

This is an outdoor event frequented and enjoyed by Franconians. Despite a relatively high number of visitors, it is not commonly known by tourists, or people living outside Bavaria.

Historical population

| Largest groups of foreign residents[24] | |

| Nationality | Population (2018) |

|---|---|

| 1,670 | |

| 1,491 | |

| 1,237 | |

| 1,171 | |

| 1,112 | |

| 934 | |

| 812 | |

| 782 | |

| 617 | |

| 581 | |

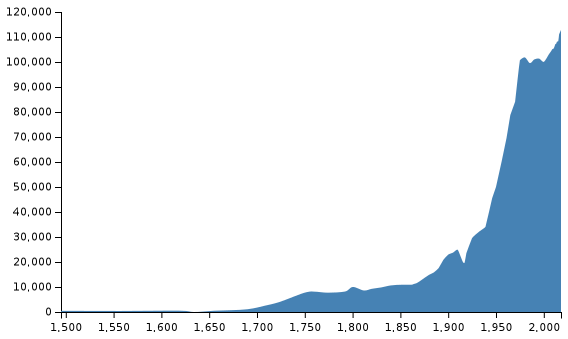

In the Middle Ages and the beginning of modern times, only a few hundred people lived in Erlangen. Due to numerous wars, epidemics and famines, the increase in population was very slow. In 1634, as a result of the destruction in the Thirty Years' War, the town was completely deserted. In 1655, the population reached 500 again, therefore reaching pre war levels. On 8 March 1708 Erlangen was declared the sixth state capital.[25] By 1760, the population had risen to over 8000. Due to the famines 1770-1772, the population declined to 7224 in 1774. After an increase to approximately 10,000 people in 1800, the population of Erlangen fell once again as a result of the Napoleonic wars and reached 8592 in 1812.

During the 19th century, this number doubled to 17,559 in 1890. Due to numerous incorporations, the population of the city rose to 30,000 by 1925 and again in the following decades, reaching 60,000 in 1956. Because of district and areal reforms in 1972, the population of the city exceeded the limit of 100,000 in 1974, making Erlangen a major city.[26]

Increased demand for urban homes has led the population to grow further in the 2000s, with predictions claiming the city would reach over 115,000 residents in the 2030s within the current urban area.[27]

|

|

|

|

|

Mayors of Erlangen

- 1818–1827: Johann Sigmund Lindner

- 1828–1855: Johann Wolfgang Ferdinand Lammers

- 1855–1865: Carl Wolfgang Knoch

- 1866–1872: Heinrich August Papellier

- 1872–1877: Johann Edmund Reichold

- 1878–1880: Friedrich Scharf

- 1881–1892: Georg Ritter von Schuh

- 1892–1929: Theodor Klippel

- 1929–1934: Hans Flierl

- 1934–1944: Alfred Groß (NSDAP)

- 1944–1945: Herbert Ohly (NSDAP)

- 1945–1946: Anton Hammerbacher (SPD)

- 1946–1959: Michael Poeschke (SPD)

- 1959–1972: Heinrich Lades (CSU)

- 1972–1996: Dietmar Hahlweg (SPD)

- 1996–2014: Siegfried Balleis (CSU)

- 2014–present: Florian Janik (SPD)

International relations

Erlangen is twinned with several cities:

Further partnerships

Erlangen is also the base of the Deutsch-Französisches Institut.[40]

Notable residents

Though a small village for much of its history and now only a small city of only 100k inhabitants, Erlangen has made significant contributions to the world, primarily through its many Lutheran theologians, to its University of Erlangen-Nuremberg scholars, and the Siemens AG pioneers in science and technology.

.jpg)

Among its noted residents are:

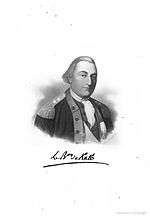

- Johann de Kalb (1721-1780), - Soldier, War of Austrian Succession, Seven Years' War, Major General in the American Revolutionary War, namesake of many American towns

- Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller (1725-1776), - zoologist, known to the classification of several new species, especially birds

- Eugenius Johann Christoph Esper (1742-1810), - scientist, botanist, first to begin research into Paleopathology

- Johann Schweigger - (1779-1857), chemist, physicist, mathematician, named "Chlorine", and invented the Galvanometer

- August Friedrich Schweigger (1783-1921), - botanist, zoologist, known for taxonomy including the discovery of several turtle species

- Georg Ohm - (1789-1854), German scientist, famous for Ohm's Law regarding electric current, and the measurement unit Ohm

- Karl Heinrich Rau - (1792-1870), economist, published an influential encyclopedia of all "relevant" economic knowledge of his time

- Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius - (1794-1868), botanist, explorer, famous expedition into Brazil (1817-1820)

- Adolph Wagner - (1835-1917), economist, founding proponent of Academic Socialism and State Socialism

- Paul Zweifel (1848-1927), - gynecologist, proved that the fetus was metabolically active, paving the way for new fetal research

- Emmy Noether - (1882-1935), mathematician, groundbreaking work on abstract algebra and theoretical physics

- Fritz Noether (1884-1941), - mathematician, political prisoner, younger brother of Emmy Noether, imprisoned in Soviet Russia

- Ernst Penzoldt - (1892-1955), artist, famous German author, painter, and sculptor

- Eduard Hauser (soldier) (1895-1961), - German officer, general in World War II,

- Heinrich Welker - (1912-1981), theoretical physicist, made numerous inventions in the early electrical engineering fields

- Rudolf Fleischmann (1903-2002), - scientist, nuclear physicist, member of the Uranium Club, theorist on isotope separation

- Bernhard Plettner - (1914-1997), electrical engineer and Business Administration, CEO for Siemens AG (1971-1981)

- Helmut Zahn (1916-2004), - scientist, chemist, one of the first to discover the properties of Insulin

- Walter Krauß (1917-1943), - Luftwaffe officer

- Hans Lotter (1917-2008), - officer in World War II, escaped from POW camp and wrote memoirs about it

- Georg Nees - (1926-2016), Graphic Artist, expanded ALGOL computer language, pioneer in digital art and sculptures

- Elke Sommer - (born 1940), entertainer, Golden Globe Award winning actress from television and film, early Playboy playmate

- Heinrich von Pierer - (born 1941), Business Administration, CEO for Siemens AG (1992-2005), advisor to numerous governmental figures

- Gerhard Frey - (born 1944), mathematician, worked on Elliptic Curve and helped prove Fermat's Last Theorem

- Karl Meiler - (1949-2014), tennis player, moderately successful in Doubles Tennis in the 1970s.

- Karlheinz Brandenburg - (born 1954), sound engineer, contributor to the invention of the format MPEG Audio Layer III, or MP3

- Klaus Täuber - (born 1958), footballer, played for several Bundesliga teams from the mid 1970s-1980s, managed at lower levels

- Lothar Matthäus - (born 1961), German Football legend, World Cup Winning Captain, Bayern Captain, first FIFA World Player of the Year

- Willi Kalender - medical physicist, pioneer in CT Scan technology and research into numerous diseases

- Jürgen Teller - (born 1964), fine art and fashion photography, worked for numerous magazines and designers, often with Björk

- Hisham Zreiq - (born 1968), award-winning Palestinian Christian Independent filmmaker, poet and visual artist.

- Peter Wackel - (born 1977), singer, with 6 albums and over 25 singles, he has a niche singing Schlager musik

- Flula Borg - (born 1982), entertainer, DJ, hip-hop artist, internet sensation, film critic

- Michael Buehl - (born 1962), professor of chemistry, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK

For a more complete list, visit Category:People from Erlangen

References

- ↑ "Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes". Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik und Datenverarbeitung (in German). September 2018.

- ↑ "Begründung - Natur und Landschaft" (PDF). Nuernberg.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "Regnitz River | river, Germany". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-18). "Sozialstruktur in den Bezirken". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "Kosbach, Häusling und Steudach wurden vor 40 Jahren eingemeindet" (PDF). lehninger.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "Chronik Eltersdorf". www.sk-eltersdorf.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ www.lexolino.de. "lexolino.de - Erlangen in Geographie,Kontinente,Europa,Staaten,Deutschland,Städte". www.lexolino.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- 1 2 Weißmüller, Wolfgang (2002). Vorgeschichte im Erlanger Raum. Begleitheft zur Dauerausstellung. Stadtmuseum Erlangen.

- ↑ "Dauerausstellung". www.erlangen.de (in German). 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ↑ "Sachverständiger Gutachter Wertermittlung von Immobilien". www.immobiliensachverstaendige-erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ↑ "Kosbacher Altar im "Geheimen Gongland" › Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ↑ "Der Kosbacher Altar erzählt" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ↑ Roth, Matthias. "Kosbacher Altar". www.franken-tour.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ↑ "Ausführliche Dokumentation zur Fundstelle Kosbach". uni-erlangen.de.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jakob, Andreas (1990). Die Entwicklung der Altstadt Erlangen, Jahrbuch für fränkische Landesforschung. Neustadt a. d. Aisch. pp. 37, 95–96, 101. ISBN 3-7686-9108-1 Check

|isbn=value: checksum (help). - ↑ "dMGH | Band | Diplomata [Urkunden] (DD)O II / O III: Otto II. und Otto III. (DD O II / DD O III)| Diplome". www.dmgh.de. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ↑ "dMGH | Band | Diplomata [Urkunden] (DD)H II: Heinrich II. und Arduin (DD H II) | Diplome". www.mgh.de. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ↑ "dMGH|Band |Diplomata Urkunden (DD) H II: Heinrich II. und Arduin(DD H II)| Diplome". www.mgh.de. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

- 1 2 3 Lammers, Ferdinand (1834). Geschichte der Stadt Erlangen. Erlangen. pp. 17, 27, 183, 189.

- 1 2 Bischoff, Johannes (1984). Die Siedlung in den ersten Jahrhunderten. Munich: Alfred Wendehorst. pp. 20, 23. ISBN 3-406-09412-0.

- 1 2 Endres, Rudolf (1984). Erlangen. Geschichte der Stadt in Darstellung und Bilddokumenten. Munich: Alfred Wendehorst. pp. 31, 33, 40, 41.

- ↑ "Im Untergrund von Erlangen: Die Kellerführung vom Entlas Keller // hombertho.de // 2010, Bergkerwa, Bier, Erlangen, Fotos, Kellerführung, Mai, Party". Hombertho.de. 2010-04-18. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "Der Entlaskeller - Kellerführungen". Entlaskeller.de. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "Ausländer nach Staatsangehörigkeit". Stadt Erlangen. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ Jakob, Andreas (2007-09-09). ""Das Himmelreich zu Erlangen – offen aus Tradition?"" (PDF). erlangen.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "Erlangen – Bayerns achtgrößte Stadt | Erlanger Historikerseite". www.erlangerhistorikerseite.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "Statistisches Jahrbuch 2017" (PDF). erlangen.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Städtepartnerschaften". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Germany, nordbayern.de, Nürnberg,. "45 Jahre Erlangen - Rennes" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Wladimir". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "Erlangen" (in German). 2011-12-22. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Stoke-on-Trent". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "San Carlos". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Beşiktaş". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Germany, nordbayern.de, Nürnberg,. "Erlangen besiegelt Städtepartnerschaft mit Riverside" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Städtepartnerschaften". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Shenzhen". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Partnerstädte - Archiv". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Germany, nordbayern.de, Nürnberg,. "Erlangen besiegelt Freundschaft mit Cumiana" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "IMPRESSUM". www.dfi-erlangen.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Erlangen. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Erlangen. |

- Official website

- erlangeninfo.de Erlangen City Guide

- University of Erlangen

- Ferris Barracks – former US Army Kaserne in Erlangen