Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

| Charles V | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Reign | 28 June 1519 – 27 August 1556 | ||||

| Coronation | |||||

| Predecessor | Maximilian I | ||||

| Successor | Ferdinand I | ||||

| King of Spain | |||||

| Reign | 23 January 1516 – 16 January 1556 | ||||

| Predecessor |

Joanna (Castile) Ferdinand II (Aragon) | ||||

| Successor | Philip II | ||||

| Co-monarch | Joanna | ||||

| Reign | 25 September 1506 – 25 October 1555[1] | ||||

| Predecessor | Philip of Castile | ||||

| Successor | Philip II of Spain | ||||

| Archduke of Austria | |||||

| Reign | 12 January 1519 – 28 April 1521 | ||||

| Predecessor | Maximilian I | ||||

| Successor | Ferdinand I | ||||

| Born |

24 February 1500 Ghent, Flanders, Habsburg Netherlands | ||||

| Died |

21 September 1558 (aged 58) Yuste, Spain | ||||

| Burial | El Escorial, San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain | ||||

| Spouse | Isabella of Portugal | ||||

| Issue see full list | Illegitimate: | ||||

| |||||

| House | Habsburg | ||||

| Father | Philip of Castile | ||||

| Mother | Joanna of Castile | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature |

| ||||

Charles V (Spanish: Carlos; German: Karl; Italian: Carlo; Dutch: Karel; Latin: Carolus; French: Charles Quint; [a] 24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was ruler of both the Holy Roman Empire from 1519 and the Spanish Empire (as Charles I of Spain) from 1516, as well as of the lands of the former Duchy of Burgundy from 1506. He stepped down from these and other positions by a series of abdications between 1554 and 1556. Through inheritance, he brought together under his rule extensive territories in western, central, and southern Europe, and the Spanish viceroyalties in the Americas and Asia. As a result, his domains spanned nearly 4 million square kilometres (1.5 million square miles), and were the first to be described as "the empire on which the sun never sets".[2]

Charles was the heir of three of Europe's leading dynasties: Valois of Burgundy, Habsburg of Austria, and Trastámara of Spain. As heir of the House of Burgundy, he inherited areas in the Netherlands and around the eastern border of France. As a Habsburg, he inherited Austria and other lands in central Europe, and was also elected to succeed his grandfather, Maximilian I, as Holy Roman Emperor. As a grandson of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, from the Spanish House of Trastámara he inherited the Crown of Castile, which was developing a nascent empire in the Americas and Asia, and the Crown of Aragon, which included a Mediterranean empire extending to southern Italy. Charles was the first king to rule Castile and Aragon simultaneously in his own right (as a unified Spain), and as a result he is often referred to as the first king of Spain.[3][lower-alpha 1] The personal union under Charles of the Holy Roman Empire with the Spanish Empire was the closest Europe has come to a universal monarchy[4] since the time of Charlemagne in the 9th century.

Because of widespread fears that his vast inheritance would lead to the realization of a universal monarchy and that he was trying to create a European hegemony, Charles was the object of hostility from many enemies.[5] His reign was dominated by war, particularly by three major simultaneous prolonged conflicts: the Italian Wars with France, the struggle to halt the Turkish advance into Europe, and the conflict with the German princes resulting from the Protestant Reformation.[6] The French wars, mainly fought in Italy, lasted for most of his reign. Enormously expensive, they led to the development of the first modern professional army in Europe, the Tercios.

The struggle with the Ottoman Empire was fought in Hungary and the Mediterranean. The Turkish advance was halted at the Siege of Vienna in 1529, and a lengthy war of attrition, conducted on Charles' behalf by his younger brother Ferdinand (King of Hungary and archduke of Austria), continued for the rest of Charles's reign. In the Mediterranean, although there were some successes, he was unable to prevent the Ottomans' increasing naval dominance and the piratical activity of the Barbary pirates. Charles opposed the Reformation, and in Germany he was in conflict with Protestant nobles who were motivated by both religious and political opposition to him. He could not prevent the spread of Protestantism and was ultimately forced to concede the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, which divided Germany along denominational lines.

While Charles did not typically concern himself with rebellions, he was quick to put down three particularly dangerous rebellions; the Revolt of the Comuneros in Castile, the revolt of the Arumer Zwarte Hoop in Frisia, and, later in his reign, the Revolt of Ghent (1539). Once the rebellions were quelled the essential Castilian and Burgundian territories remained mostly loyal to Charles throughout his rule.

Charles's Spanish dominions were the chief source of his power and wealth, and they became increasingly important as his reign progressed. In the Americas, Charles sanctioned the conquest by Castilian conquistadores of the Aztec and Inca empires. Castilian control was extended across much of South and Central America. The resulting vast expansion of territory and the flows of South American silver to Castile had profound long term effects on Spain.

Charles was only 56 when he abdicated, but after 40 years of active rule he was physically exhausted and sought the peace of a monastery, where he died at the age of 58. The Holy Roman Empire passed to his younger brother Ferdinand, archduke of Austria, while the Spanish Empire, including the possessions in the Netherlands and Italy, was inherited by Charles's son Philip II of Spain. The two empires would remain allies until the 18th century (when the Spanish branch of the House of Habsburg became extinct).

Heritage and early life

Charles was born in 1500 as the eldest son of Philip the Handsome and Joanna of Castile in the Flemish city of Ghent, which was part of the Habsburg Netherlands.[7] The culture and courtly life of the Burgundian Low Countries were an important influence in his early life. He was tutored by William de Croÿ (who would later become his first prime minister), and also by Adrian of Utrecht (later Pope Adrian VI). It is said that Charles spoke several vernacular languages: he was fluent in French and Dutch, later adding an acceptable Castilian Spanish (which Charles called the "divine language"[8]) required by the Castilian Cortes Generales as a condition for becoming King of Castile. He also gained a decent command of German (in which he was not fluent prior to his election), though he never spoke it as well as French.[9] A witticism sometimes attributed to Charles is: "I speak Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men and German to my horse." A variant of the quote is attributed to him by Swift in his 1726 Gulliver's Travels, but there are many other variants and it is often attributed instead to Frederick the Great.[10]

From his Burgundian ancestors he inherited an ambiguous relationship with the Kings of France. Charles shared with France his mother tongue and many cultural forms. In his youth he made frequent visits to Paris, then the largest city of Western Europe. In his words: "Paris is not a city, but a world" (Lutetia non urbs, sed orbis). He was betrothed to both Louise and Charlotte of Valois, daughters of King Francis I of France, but they both died in childhood. Charles also inherited the tradition of political and dynastic enmity between the royal and the Burgundian ducal lines of the Valois dynasty. Charles was very attached to the Burgundian Low Countries where he had been raised. These lands were very rich and contributed significantly to the wealth of the Empire. He also spent much time there, mainly in Brussels. This stands in contrast with the attitude of his son Philip who only visited the Low Countries once.

Until the 1540s, Charles did not spend much time in Germany. He frequently was in Northern Italy (then part of the Holy Roman Empire). He never actually governed his Austrian dominions and made his brother Ferdinand the ruler of these lands in 1521, as well as his representative in the Holy Roman Empire during his absence. In spite of this, the Emperor had a close relationship with some German families, like the House of Nassau, many of which were represented at his court in Brussels. Some German princes or noblemen accompanied him in his military campaigns against France or the Ottomans, and the bulk of his army was generally composed of German troops, especially the Imperial Landsknechte.[11]

Indeed, in 1519, he was elected because he was considered a German prince while his main opponent was French. Nonetheless, in the long term, the growth of Lutheranism and Charles' staunch Catholicism alienated him from various German princes who finally fought against him in the 1540s and the 1550s. It is important to note, though, that other states of the Empire chose to support him in his war, and that he had the constant support of his brother, in spite of their strained personal relationship.[12] Whereas Charles spent much of his final years as a ruler trying to address the issue of religion in the Empire, it would ultimately be Ferdinand, by then much more popular in Germany, who would bring peace to the German lands.

Though Spain was the core of his personal possessions and though he had many Iberian ancestors, in his earlier years Charles felt as if he were viewed as a foreign prince. He became fluent in Spanish late in his life, as it was not his first language. Nonetheless, he spent much of his life in Spain, including his final years in a Spanish monastery, and his heir, later Philip II, was born and raised in Spain. Indeed, Charles's motto, Plus Ultra ('Further Beyond'), became the national motto of Spain. He had many Spanish counselors and, except for the revolt of the comuneros in the 1520s, Spain remained mostly loyal to him. Spain was also his most important military asset, as it provided a great number of generals, as well as the formidable Spanish tercios, considered the best infantry of its time. Many Spaniards, however, believed that their resources were being used to sustain a policy that was not in the country's interest.[13] They usually believed that Charles should have focused on the Mediterranean and North Africa instead of Northern or Central Europe.

Portrait gallery

Woodcut portrait, of a young Charles V

Woodcut portrait, of a young Charles V Bernhard Strigel, Charles V in 1516, detail

Bernhard Strigel, Charles V in 1516, detail Portrait by Bernard van Orley of Charles V, 1519 - showing detail of the firesteel in the collar

Portrait by Bernard van Orley of Charles V, 1519 - showing detail of the firesteel in the collar- Medal, Conrad Meit, c. 1520

Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1533

Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1533_Flemish.tiff.png) Portrait from 1514–1516 by an unknown Flemish artist, showing an unrestrained caricature of Charles' jaw

Portrait from 1514–1516 by an unknown Flemish artist, showing an unrestrained caricature of Charles' jaw- Thaler coin, Lübeck, 1537

Reign

Burgundy and the Low Countries

In 1506, Charles inherited his father's Burgundian territories, most notably the Low Countries and Franche-Comté. Most of the holdings were fiefs of the German Kingdom (part of the Holy Roman Empire), except his birthplace of Flanders, which was still a French fief, a last remnant of what had been a powerful player in the Hundred Years' War. As he was a minor, his aunt Margaret of Austria (born as Archduchess of Austria and in both her marriages as the Dowager Princess of Asturias and Dowager Duchess of Savoy) acted as regent, as appointed by Emperor Maximilian until 1515. She soon found herself at war with France over the question of Charles' requirement to pay homage to the French king for Flanders, as his father had done. The outcome was that France relinquished its ancient claim on Flanders in 1528.

From 1515 to 1523, Charles's government in the Netherlands also had to contend with the rebellion of Frisian peasants (led by Pier Gerlofs Donia and Wijard Jelckama). The rebels were initially successful but after a series of defeats, the remaining leaders were captured and decapitated in 1523.

Charles extended the Burgundian territory with the annexation of Tournai, Artois, Utrecht, Groningen and Guelders. The Seventeen Provinces had been unified by Charles's Burgundian ancestors, but nominally were fiefs of either France or the Holy Roman Empire. In 1549, Charles issued a Pragmatic Sanction, declaring the Low Countries to be a unified entity of which his family would be the heirs.[14]

The Low Countries held an important place in the Empire. For Charles V personally they were his home, the region where he was born and spent his childhood. Because of trade and industry and the wealth of the region's cities, the Low Countries also represented an important income for the Imperial treasury.

The Burgundian territories were generally loyal to Charles throughout his reign. The important city of Ghent rebelled in 1539 due to heavy tax payments demanded by Charles. The rebellion did not last long, however, as Charles's military response, with reinforcement from the Duke of Alba,[14] was swift and humiliating to the rebels of Ghent.[15][16]

Spain

In the Castilian Cortes of Valladolid in 1506 and of Madrid in 1510, Charles was sworn as the Prince of Asturias, heir-apparent to his mother the Queen Joanna.[19] On the other hand, in 1502, the Aragonese Corts gathered in Saragossa and pledged an oath to Joanna as heiress-presumptive, but the Archbishop of Saragossa expressed firmly that this oath could not establish jurisprudence, that is to say, modify the right of the succession, except by virtue of a formal agreement between the Cortes and the King.[20][21] So, upon the death of King Ferdinand II of Aragon, on 23 January 1516, Joanna inherited the Crown of Aragon, which consisted of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Naples, Sicily and Sardinia, while Charles became Governor General.[22] Nevertheless, the Flemings wished Charles to assume the royal title, and this was supported by his grandfather the emperor Maximilian I and Pope Leo X.

Thus, after the celebration of Ferdinand II's obsequies on 14 March 1516, Charles was proclaimed king of the crowns of Castile and Aragon jointly with his mother. Finally, when the Castilian regent Cardinal Jiménez de Cisneros accepted the fait accompli, he acceded to Charles's desire to be proclaimed king and imposed his enstatement throughout the kingdom.[23] Charles arrived in his new kingdoms in autumn of 1517. Jiménez de Cisneros came to meet him but fell ill along the way, not without a suspicion of poison, and he died before meeting the King.[24]

Due to the irregularity of Charles assuming the royal title while his mother, the legitimate queen, was alive, the negotiations with the Castilian Cortes in Valladolid (1518) proved difficult.[25] In the end Charles was accepted under the following conditions: he would learn to speak Castilian; he would not appoint foreigners; he was prohibited from taking precious metals from Castile; and he would respect the rights of his mother, Queen Joanna. The Cortes paid homage to him in Valladolid in February 1518. After this, Charles departed to the crown of Aragon. He managed to overcome the resistance of the Aragonese Cortes and Catalan Corts,[26] and he was finally recognized as king of Aragon and count of Barcelona jointly with his mother.[27] The Kingdom of Navarre had been invaded by Ferdinand of Aragon jointly with Castile in 1512, but he pledged a formal oath to respect the kingdom. On Charles's accession to the Spanish throne, the Parliament of Navarre (Cortes) required him to attend the coronation ceremony (to become Charles IV of Navarre), but this demand fell on deaf ears, and the Parliament kept piling up grievances.

Charles was accepted as sovereign, even though the Spanish felt uneasy with the Imperial style. Spanish kingdoms varied in their traditions. Castile was an authoritarian kingdom, where the monarch's own will easily overrode law and the Cortes. By contrast, in the kingdoms of the crown of Aragon, and especially in the Pyrenean kingdom of Navarre, law prevailed, and the monarchy was a contract with the people. This became an inconvenience and a matter of dispute for Charles V and later kings, since realm-specific traditions limited their absolute power. With Charles, government became more absolute, even though until his mother's death in 1555 Charles did not hold the full kingship of the country.

Soon resistance to the Emperor arose because of heavy taxation to support foreign wars in which Castilians had little interest, and because Charles tended to select Flemings for high offices in Spain and America, ignoring Castilian candidates. The resistance culminated in the Revolt of the Comuneros, which Charles suppressed. Immediately after crushing the Castilian revolt, Charles was confronted again with the hot issue of Navarre when King Henry II attempted to reconquer the kingdom. Main military operations lasted until 1524, when Hondarribia surrendered to Charles's forces, but frequent cross-border clashes in the western Pyrenees only stopped in 1528 (Treaties of Madrid and Cambrai).

After these events, Navarre remained a matter of domestic and international litigation still for a century (a French dynastic claim to the throne did not end until the French Revolution in 1789). Charles wanted his son and heir Philip II to marry the heiress of Navarre, Jeanne d'Albret. Jeanne was instead forced to marry William, Duke of Julich-Cleves-Berg, but that childless marriage was annulled after four years. She next married Antoine de Bourbon, and both she and their son would oppose Philip II in the French Wars of Religion.

Castile became integrated into Charles's empire, and provided the bulk of the empire's financial resources as well as its most effective military units. The enormous budget deficit accumulated during Charles's reign resulted in Spain declaring bankruptcy during the reign of Philip II.[28]

Italy

The Crown of Aragon inherited by Charles included the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Sicily and the Kingdom of Sardinia. Aragon also previously controlled the Duchy of Milan, but a year before Charles ascended to the throne, it was annexed by France after the Battle of Marignano in 1515. Charles succeeded in re-capturing Milan in 1522, when Imperial troops defeated the Franco-Swiss army at Bicocca. Yet in 1524 Francis I of France retook the initiative, crossing into Lombardy where Milan, along with a number of other cities, once again fell to his attack. Pavia alone held out, and on 24 February 1525 (Charles's twenty-fifth birthday), Charles's Spanish forces captured Francis and crushed his army in the Battle of Pavia, yet again retaking Milan and Lombardy. Spain successfully held on to all of its Italian territories, though they were invaded again on multiple occasions during the Italian Wars.

In addition, Habsburg trade in the Mediterranean was consistently disrupted by the Ottoman Empire. In 1538 a Holy League consisting of all the Italian states and Spain was formed to drive the Ottomans back, but it was defeated at the Battle of Preveza. Decisive naval victory eluded Charles; it would not be achieved until after Charles's death, at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

America

During Charles's reign, the Spanish territories in the Americas were considerably extended by conquistadores like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro. They conquered the large Aztec and Inca empires and incorporated them into the Empire as the Viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru between 1519 and 1542. Combined with the circumnavigation of the globe by the Magellan expedition in 1522, these successes convinced Charles of his divine mission to become the leader of Christendom, which still perceived a significant threat from Islam. The conquests also helped solidify Charles's rule by providing the state treasury with enormous amounts of bullion. As the conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo observed, "We came to serve God and his Majesty, to give light to those in darkness, and also to acquire that wealth which most men covet."[29]

On 28 August 1518 Charles issued a charter authorising the transportation of slaves direct from Africa to the Americas. Up until that point (since at least 1510), African slaves had usually been transported to Spain or Portugal and had then been transhipped to the Caribbean. Charles’s decision to create a direct, more economically viable Africa to America slave trade fundamentally changed the nature and scale of this terrible human trafficking industry. [30]

In 1528 Charles assigned a concession in Venezuela Province to Bartholomeus V. Welser, in compensation for his inability to repay debts owed. The concession, known as Klein-Venedig (little Venice), was revoked in 1546. In 1550, Charles convened a conference at Valladolid in order to consider the morality of the force used against the indigenous populations of the New World, which included figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas.

Charles V is credited with the first idea of constructing an American Isthmus canal in Panama as early as 1520.[31]

Holy Roman Empire

.jpg)

After the death of his paternal grandfather, Maximilian, in 1519, Charles inherited the Habsburg Monarchy. He was also the natural candidate of the electors to succeed his grandfather as Holy Roman Emperor. He defeated the candidacies of Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, Francis I of France, and Henry VIII of England. The electors gave Charles the crown on 28 June 1519. On 26 October 1520 he was crowned in Germany and some ten years later, on 22 February 1530, he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Clement VII in Bologna, the last emperor to receive a papal coronation.[32][33]

Despite holding the imperial throne, Charles's real authority was limited by the German princes. They gained a strong foothold in the Empire's territories, and Charles was determined not to let this happen in the Netherlands. An inquisition was established as early as 1522. In 1550, the death penalty was introduced for all cases of unrepentant heresy. Political dissent was also firmly controlled, most notably in his place of birth, where Charles, assisted by the Duke of Alba, personally suppressed the Revolt of Ghent in mid-February 1540.[14]

Charles abdicated as emperor in 1556 in favor of his brother Ferdinand; however, due to lengthy debate and bureaucratic procedure, the Imperial Diet did not accept the abdication (and thus make it legally valid) until 24 February 1558. Up to that date, Charles continued to use the title of emperor.

France

Much of Charles's reign was taken up by conflicts with France, which found itself encircled by Charles's empire while it still maintained ambitions in Italy. In 1520, Charles visited England, where his aunt, Catherine of Aragon, urged her husband, Henry VIII, to ally himself with the emperor. In 1508 Charles was nominated by Henry VII to the Order of the Garter.[34] His Garter stall plate survives in Saint George's Chapel.

The first war with Charles's great nemesis Francis I of France began in 1521. Charles allied with England and Pope Leo X against the French and the Venetians, and was highly successful, driving the French out of Milan and defeating and capturing Francis at the Battle of Pavia in 1525. To gain his freedom, Francis ceded Burgundy to Charles in the Treaty of Madrid, as well as renouncing his support of Henry II's claim over Navarre.

.jpg)

When he was released, however, Francis had the Parliament of Paris denounce the treaty because it had been signed under duress. France then joined the League of Cognac that Pope Clement VII had formed with Henry VIII of England, the Venetians, the Florentines, and the Milanese to resist imperial domination of Italy. In the ensuing war, Charles's sack of Rome (1527) and virtual imprisonment of Pope Clement VII in 1527 prevented the Pope from annulling the marriage of Henry VIII of England and Charles's aunt Catherine of Aragon, so Henry eventually broke with Rome, thus leading to the English Reformation.[35][36] In other respects, the war was inconclusive. In the Treaty of Cambrai (1529), called the "Ladies' Peace" because it was negotiated between Charles's aunt and Francis' mother, Francis renounced his claims in Italy but retained control of Burgundy.

A third war erupted in 1536. Following the death of the last Sforza Duke of Milan, Charles installed his son Philip in the duchy, despite Francis' claims on it. This war too was inconclusive. Francis failed to conquer Milan, but he succeeded in conquering most of the lands of Charles's ally, the Duke of Savoy, including his capital Turin. A truce at Nice in 1538 on the basis of uti possidetis ended the war but lasted only a short time. War resumed in 1542, with Francis now allied with Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I and Charles once again allied with Henry VIII. Despite the conquest of Nice by a Franco-Ottoman fleet, the French could not advance toward Milan, while a joint Anglo-Imperial invasion of northern France, led by Charles himself, won some successes but was ultimately abandoned, leading to another peace and restoration of the status quo ante bellum in 1544.

A final war erupted with Francis' son and successor, Henry II, in 1551. Henry won early success in Lorraine, where he captured Metz, but French offensives in Italy failed. Charles abdicated midway through this conflict, leaving further conduct of the war to his son, Philip II, and his brother, Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor.

Conflicts with the Ottoman Empire

Charles fought continually with the Ottoman Empire and its sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent. The defeat of Hungary at the Battle of Mohács in 1526 "sent a wave of terror over Europe."[37][38] The Muslim advance in Central Europe was halted at the Siege of Vienna in 1529.

Suleiman won the contest for mastery of the Mediterranean, in spite of Spanish victories such as the conquest of Tunis in 1535. The regular Ottoman fleet came to dominate the Eastern Mediterranean after its victories at Preveza in 1538 and Djerba in 1560 (shortly after Charles's death), which severely decimated the Spanish marine arm. At the same time, the Muslim Barbary corsairs, acting under the general authority and supervision of the sultan, regularly devastated the Spanish and Italian coasts, crippling Spanish trade and chipping at the foundations of Habsburg power.

In 1536 Francis I of France allied himself with Suleiman against Charles. While Francis was persuaded to sign a peace treaty in 1538, he again allied himself with the Ottomans in 1542 in a Franco-Ottoman alliance. In 1543 Charles allied himself with Henry VIII and forced Francis to sign the Truce of Crépy-en-Laonnois. Later, in 1547, Charles signed a humiliating[39] treaty with the Ottomans to gain himself some respite from the huge expenses of their war.[40]

Charles V made overtures to the Safavid Empire to open a second front against the Ottomans, in an attempt at creating a Habsburg-Persian alliance. Contacts were positive, but rendered difficult by enormous distances. In effect, however, the Safavids did enter in conflict with the Ottoman Empire in the Ottoman-Safavid War, forcing it to split its military resources.[41]

Protestant Reformation

The issue of the Protestant Reformation was first brought to the imperial attention under Charles V. As Holy Roman Emperor, Charles called Martin Luther to the Diet of Worms in 1521, promising him safe conduct if he would appear. Initially dismissing Luther's theses as "an argument between monks", he later outlawed Luther and his followers in that same year but was tied up with other concerns and unable to take action against Protestantism. The Peasants' Revolt in Germany, fueled by Anabaptist rhetoric, broke out from 1524 to 1526, and in 1531 the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League was formed. Charles delegated increasing responsibility for Germany to his brother Ferdinand while he concentrated on problems elsewhere.

In 1545, the opening of the Council of Trent began the Counter-Reformation and the Catholic cause was also supported by some of the princes of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1546 (the year of Luther's death), he outlawed the Schmalkaldic League (which had occupied the territory of another prince). The next year his forces drove the League's troops out of southern Germany, and defeated John Frederick, Elector of Saxony and Philip of Hesse at the Battle of Mühlberg, capturing both. At the Augsburg Interim in 1548, he created a solution giving certain allowances to Protestants until the Council of Trent would restore unity. However, members of both sides resented the Interim and some actively opposed it. In 1552 Protestant princes, in alliance with Henry II of France, rebelled again, which caused Charles to retreat to the Netherlands.

Marriage

During his lifetime, Charles V had several mistresses, but only during his bachelorhood and only once during his widowhood; there are no records of him ever having had any extramarital affairs during his marriage.

On 21 December 1507, Charles was first betrothed to 11-year old Mary, the daughter of King Henry VII of England and younger sister to the future King Henry VIII of England, who was to take the throne in two years. However, the engagement was called off in 1513 on the advice of Thomas Wolsey and Mary was instead married off to King Louis XII of France in 1514.

After his ascension to the Spanish throne, negotiations for Charles's marriage began shortly after his arrival in Spain, with the Spanish nobles expressing their wishes for him to marry his first cousin Isabella of Portugal, the daughter of King Manuel I of Portugal and Charles's aunt Maria of Aragon. The nobles desired for Charles to marry a princess of Spanish blood and a marriage to Isabella would secure an alliance between Spain and Portugal. The 18 year old King, however, was in no hurry to marry and ignored the nobles' advice. Instead of marrying Isabella, he sent his sister Eleanor to marry Isabella's widowed father King Manuel in 1518. In 1521, on the advice of his Flemish advisors, especially William de Croÿ, Charles became engaged to his other first cousin, Mary, daughter of his aunt Catherine of Aragon and King Henry VIII, in order to secure an alliance with England. However, this engagement was very problematic since Mary was only 6 years old at the time, sixteen years Charles's junior, which meant that he would have to wait for her to be old enough to marry.

By 1525, Charles was no longer interested in an alliance with England and could not wait any longer to have legitimate children and heirs. Following his victory in the Battle of Pavia, Charles abandoned the idea of an English alliance, cancelled his engagement to Mary and decided to marry Isabella and form an alliance with Portugal. He wrote to Isabella's brother King John III of Portugal, making a double marriage contract - Charles would marry Isabella and John would marry Charles's youngest sister Catherine. A marriage to Isabella was more beneficiary for Charles, as she was closer to him in age, was fluent in Spanish and provided him with a very handsome dowry of 900,000 Portuguese cruzados or Castilian folds that would help to solve his financial problems brought on by the Italian Wars.

On 10 March 1526, Charles and Isabella met at the Alcázar Palace in Seville. The marriage was originally a political arrangement, but on their first meeting, the couple fell deeply in love, with Isabella captivating the Emperor with her beauty and charm. They were married that very same night in a quiet ceremony in the Hall of Ambassadors just after midnight. Following their wedding, Charles and Isabella spent a long and happy honeymoon at the Alhambra in Granada. Wishing to establish their residence in the Alhambra palaces, Charles began the construction of the Palace of Charles V in 1527, which was intended as a permanent residence befitting an emperor and empress. However, the palace was not completed during their lifetime and remained roofless until the late 20th century.[42]

Despite the Emperor's long absences due to political affairs abroad, the marriage was a happy one, as both partners were always devoted and faithful to each other.[43] The Empress acted as regent of Spain during her husband's absences and she proved herself to be a good politician and ruler, thoroughly impressing the Emperor with many of her political gains and decisions.

The marriage lasted for thirteen years until Isabella's death in 1539. The Empress contracted a fever during the third month of her seventh pregnancy, which resulted in antenatal complications that caused her to miscarry to a stillborn son. Her health further deteriorated due to an infection and she died two weeks later on 1 May 1539, aged 35. Charles was left so grief-stricken by his wife's death that he shut himself up in a monastery for two months where he prayed and mourned for her in solitude.[44] In the aftermath, Charles never recovered from Isabella's death, dressing in black for the rest of his life to show his eternal mourning, and, unlike most kings of the time, he never remarried. In memory of his wife, the Emperor commissioned the painter Titian to paint several posthumous portraits of Isabella; the portraits that were produced included Titian's Portrait of Empress Isabel of Portugal and La Gloria.[45] Charles kept these portraits with him whenever he travelled and they were among those that he later brought with him to the Monastery of Yuste in 1557 after his retirement.[46]

Charles also paid tribute to Isabella's memory with music when, in 1540, he commissioned the Flemish composer Thomas Crecquillon to compose new music as a memorial to her. Crecquillon composed his Missa 'Mort m'a privé in memory of the Empress, which itself expresses the Emperor's grief and great wish for a heavenly reunion with his beloved wife.[47]

Health

Charles suffered from an enlarged lower jaw, a deformity that became considerably worse in later Habsburg generations, giving rise to the term Habsburg jaw. This deformity may have been caused by the family's long history of inbreeding, which was commonly practiced in royal families of that era to maintain dynastic control of territory. He suffered from epilepsy[48] and was seriously afflicted with gout, presumably caused by a diet consisting mainly of red meat.[49] As he aged, his gout progressed from painful to crippling. In his retirement, he was carried around the monastery of St. Yuste in a sedan chair. A ramp was specially constructed to allow him easy access to his rooms.[50]

Abdications and later life

Charles abdicated the parts of his empire piecemeal. First he abdicated the thrones of Sicily and Naples, both fiefs of the Papacy, and the Duchy of Milan to his son Philip in 1554. Upon Charles's abdication of Naples on 25 July, Philip was invested with the kingdom (officially "Naples and Sicily") on 2 October by Pope Julius III. The abdication of the throne of Sicily, sometimes dated to 16 January 1556, must have taken place before Joanna's death in 1555. There is a record of Philip being invested with this kingdom (officially "Sicily and Jerusalem") on 18 November 1554 by Julius. These resignations are confirmed in Charles's will from the same year.[51] The most famous—and public—abdication of Charles took place a year later, on 25 October 1555, when he announced to the States General of the Netherlands his abdication of those territories and the county of Charolais and his intention to retire to a monastery.[51] He abdicated as ruler of the Spanish Empire in January 1556, with no fanfare, and gave these possessions to Philip.[51] On 27 August 1556, he abdicated as Holy Roman Emperor[lower-alpha 2] in favor of his brother Ferdinand, although the abdication was not formally accepted by the Electors of the Empire until 1558.[54] The delay had been at the request of Ferdinand, who had been concerned about holding a risky election in 1556.[51]

Charles retired to the Monastery of Yuste in Extremadura but continued to correspond widely and kept an interest in the situation of the empire. He suffered from severe gout. Some scholars think Charles decided to abdicate after a gout attack in 1552 forced him to postpone an attempt to recapture the city of Metz, where he was later defeated. He lived alone in a secluded monastery, with clocks lining every wall, which some historians believe were symbols of his reign and his lack of time.[55] In an act designed to "merit the favour of heaven", about six months before his death Charles staged his own funeral, complete with shroud and coffin, after which he "rose out of the coffin, and withdrew to his apartment, full of those awful sentiments, which such a singular solemnity was calculated to inspire." [56]

Death

In August 1558, Charles was taken seriously ill with what was later revealed to be malaria.[57] He died in the early hours of the morning on 21 September 1558, at the age of 58, holding in his hand the cross that his wife Isabella had been holding when she died.[58]

Charles was originally buried in the chapel of the Monastery of Yuste, but he left a codicil in his last will and testament asking for the establishment of a new religious foundation in which he would be reburied with Isabella.[59] Following his return to Spain in 1559, their son Philip undertook the task of fulfilling his father's wish when he founded the Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial. After the Monastery's Royal Crypt was completed in 1574, the bodies of Charles and Isabella were relocated and re-interred into a small vault directly underneath the altar of the famous Basilica of the Monastery, in accordance with Charles's wishes to be buried "half-body under the altar and half-body under the priest's feet" side by side with Isabella. They remained in this vault until 1654 when they were later moved into the Royal Pantheon of Kings by their great-grandson Philip IV, who, in doing so, disrespected his great-grandfather's wishes.[60]

On one side of the Basilica are bronze effigies of Charles and Isabella, with effigies of their daughter Maria of Austria and Charles's sisters Eleanor of Austria and Maria of Hungary behind them. Exactly adjacent to them on the opposite side of the Basilica are effigies of their son Philip with three of his wives and their ill-fated grandson Carlos, Prince of Asturias.

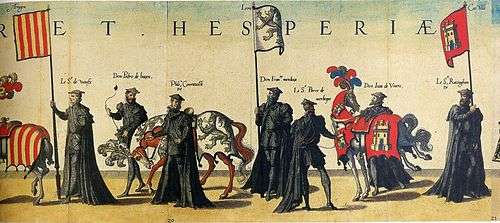

Banners with the arms of Aragon, León and Castile in the funeral at the death of Charles V. Hieronymus Cock, Funerals of Charles V, Antwerp, Cristóbal Plantino, 1559.

Banners with the arms of Aragon, León and Castile in the funeral at the death of Charles V. Hieronymus Cock, Funerals of Charles V, Antwerp, Cristóbal Plantino, 1559. Banners with the arms of Galicia in the funeral. Hieronymus Cock, Funerals of Charles V, Antwerp, Cristóbal Plantino, 1559.

Banners with the arms of Galicia in the funeral. Hieronymus Cock, Funerals of Charles V, Antwerp, Cristóbal Plantino, 1559. Banners with the arms of Sardinia in the funeral. Hieronymus Cock, Funerals of Charles V, Antwerp, Cristóbal Plantino, 1559.

Banners with the arms of Sardinia in the funeral. Hieronymus Cock, Funerals of Charles V, Antwerp, Cristóbal Plantino, 1559. Banners with the arms of Valencia in the funeral. Hieronymus Cock, Funerals of Charles V, Antwerp, Cristóbal Plantino, 1559.

Banners with the arms of Valencia in the funeral. Hieronymus Cock, Funerals of Charles V, Antwerp, Cristóbal Plantino, 1559. Mummy of the Emperor Charles V located in El Escorial, copied from the natural, of Martín Rico, in La Ilustración Española y Americana, 1872.

Mummy of the Emperor Charles V located in El Escorial, copied from the natural, of Martín Rico, in La Ilustración Española y Americana, 1872.

Issue

Charles and Isabella had seven children, though only three survived to adulthood:

| Name | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philip II of Spain |

|

21 May 1527 – 13 September 1598 |

Only surviving son, successor of his father in the Spanish crown. |

| Maria |

|

21 June 1528 – 26 February 1603 |

Married her first cousin Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor. |

| Ferdinand |

.svg.png) |

22 November 1529 – 13 July 1530 |

Died in infancy. |

| Son |

.svg.png) |

29 June 1534 | Stillborn |

| Joanna |

|

26 June 1535 – 7 September 1573 |

Married her first cousin João Manuel, Prince of Portugal. |

| John |

.svg.png) |

19 October 1537 – 20 March 1538 |

Died in infancy. |

| Son |

.svg.png) |

21 April 1539 | Stillborn. |

Due to Philip II being a grandson of Manuel I of Portugal through his mother he was in the line of succession to the throne of Portugal, and claimed it after his uncle's death (Henry, the Cardinal-King, in 1580), thus establishing the Iberian Union.

Charles also had four illegitimate children:

- Margaret of Austria (1522 – 1586), daughter of Johanna Maria van der Gheynst, a servant of Charles I de Lalaing, Seigneur de Montigny, daughter of Gilles Johann van der Gheynst and wife Johanna van der Caye van Cocamby. Married firstly with Alessandro de' Medici, Duke of Florence and secondly with Ottavio Farnese, Duke of Parma.

- Joanna of Austria (1522 – 1530), daughter of a noble lady from Nassau.

- Tadea of Austria (1523? – ca. 1562), daughter of Orsolina della Penna. Married with Sinibaldo di Copeschi.

- John of Austria (1547 – 1578), son of Barbara Blomberg, victor of the Battle of Lepanto

Historians suspect he fathered Isabel of Castile, the illegitimate daughter of his step-grandmother Germaine of Foix.

Margaret of Parma

John of Austria

Titles

| Title | Date from | Date to | Regnal name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titular Duke of Burgundy | 25 September 1506 | 16 January 1556 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Brabant | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Limburg | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Lothier | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Luxemburg | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles III | |

| Margrave of Namur | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| [61] Count Palatine of Burgundy | 25 September 1506 | 5 February 1556 | Charles II | |

| Count of Artois | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| [62] Count of Charolais | 25 September 1506 | 21 September 1558 | Charles II | |

| Count of Flanders | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles III | |

| Count of Hainault | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Count of Holland | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Count of Zeeland | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Guelders | 12 September 1543 | 25 October 1555 | Charles III | |

| Count of Zutphen | 12 September 1543 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| King of Castile and León | 14 March 1516 | 16 January 1556 | Charles I (with Joanna, 14 March 1516 – 12 April 1555) | |

| King of Aragon and Sicily | 14 March 1516 | 16 January 1556 | Charles I (with Joanna, 14 March 1516 – 12 April 1555) | |

| Count of Barcelona | 14 March 1516 | 16 January 1556 | Charles I | |

| King of Naples | 14 March 1516 | 25 July 1554 | Charles IV (with Joanna III, 14 March 1516 – 25 July 1554) | |

| King of the Romans | 28 June 1519 | 24 February 1530 | Charles V | |

| Holy Roman Emperor | 24 February 1530 | 24 February 1558 | Charles V | |

| Archduke of Austria | 12 January 1519 | 12 January 1521 | Charles I | |

The titles of King of Hungary, of Bohemia, and of Croatia, were incorporated into the imperial family during Charles's reign, but they were held, both nominally and substantively, by his brother Ferdinand, who initiated a four-century-long Habsburg rule over these eastern territories.

However, according Charles V testament, the titles of King of Hungary, of Dalmatia, and of Croatia and others were legated to his grandson, Infante Carlos, Prince of Asturias who was the son of Philip II of Spain, and who died young. Charles's full titulature went as follows:

Charles, by the grace of God, Holy Roman Emperor, forever August, King of Germany, King of Italy, King of all Spains, of Castile, Aragon, León, of Hungary, of Dalmatia, of Croatia, Navarra, Grenada, Toledo, Valencia, Galicia, Majorca, Sevilla, Cordova, Murcia, Jaén, Algarves, Algeciras, Gibraltar, the Canary Islands, King of Two Sicilies, of Sardinia, Corsica, King of Jerusalem, King of the Western and Eastern Indies, of the Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Brabant, Lorraine, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Limburg, Luxembourg, Gelderland, Neopatria, Württemberg, Landgrave of Alsace, Prince of Swabia, Asturia and Catalonia, Count of Flanders, Habsburg, Tyrol, Gorizia, Barcelona, Artois, Burgundy Palatine, Hainaut, Holland, Seeland, Ferrette, Kyburg, Namur, Roussillon, Cerdagne, Drenthe, Zutphen, Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire, Burgau, Oristano and Gociano, Lord of Frisia, the Wendish March, Pordenone, Biscay, Molin, Salins, Tripoli and Mechelen.

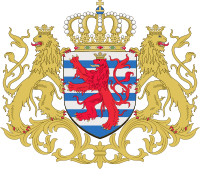

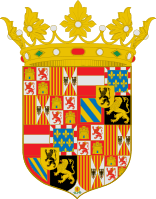

Coat of arms of Charles V

Coat of arms of Charles I of Spain and V of Germany according to the description: Arms of Charles I added to those of Castile, Leon, Aragon, Two Sicilies and Granada present in the previous coat, those of Austria, ancient Burgundy, modern Burgundy, Brabant, Flanders and Tyrol. Charles I also incorporates the pillars of Hercules with the inscription "Plus Ultra", representing the overseas empire and surrounding coat with the collar of the Golden Fleece, as sovereign of the Order ringing the shield with the imperial crown and Acola double-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire and behind it the Spanish Cross of Burgundy. From 1520 added to the corresponding quarter to Aragon and Sicily, one in which the arms of Jerusalem, Naples and Navarre are incorporated.

Coat of arms of King Charles I of Spain before becoming emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

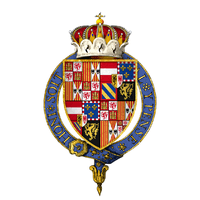

Coat of arms of King Charles I of Spain before becoming emperor of the Holy Roman Empire..svg.png) Coat of Arms of Charles I of Spain, Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor.

Coat of Arms of Charles I of Spain, Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor. Arms of Charles, Infante of Spain, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, KG at the time of his installation as a knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter.

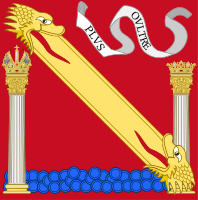

Arms of Charles, Infante of Spain, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, KG at the time of his installation as a knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. Variant of the Royal Bend of Castile used by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Variant of the Royal Bend of Castile used by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

In popular culture

References to Charles V include a large number of legends and folk tales; literary renderings of historical events connected to Charles's life and romantic adventures, his relationship to Flanders, and his abdication; and products marketed in his name.[63]

Literature

- In De heerelycke ende vrolycke daeden van Keyser Carel den V, published by Joan de Grieck in 1674, the short stories, anecdotes, citations attributed to the emperor, and legends about his encounters with famous and ordinary people, depict a noble Christian monarch with a perfect cosmopolitan personality and a strong sense of humour. Converesely, in Charles De Coster's masterpiece Thyl Ulenspiegel (1867), after his death Charles V is consigned to Hell as punishment for the acts of the Inquisition under his rule, his punishment being that he would feel the pain of anyone tortured by the Inquisition. De Coster's book also mentions the story on the spectacles in the coat of arms of Oudenaarde, the one about a paysant of Berchem in Het geuzenboek (1979) by Louis Paul Boon, while Abraham Hans (1882–1939) included both tales in De liefdesavonturen van keizer Karel in Vlaanderen.

- Lord Byron's Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte refers to Charles as "The Spaniard".

- Charles V is a notable character in Simone de Beauvoir's All Men Are Mortal.

- In The Maltese Falcon, the title object is said to have been an intended gift to Charles V.

Plays

- Charles V appears as a character in the play Doctor Faustus by the Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe. In Act 4 Scene 1 of the A Text, Faustus attends Court by the Emperor's request and with the assistance of Mephistopheles conjures up spirits representing Alexander the Great and his paramour as a demonstration of his magical powers.

Opera

- Ernst Krenek's opera Karl V (opus 73, 1930) examines the title character's career via flashbacks.

- In the third act of Giuseppe Verdi's opera Ernani, the election of Charles as Holy Roman Emperor is presented. Charles (Don Carlo in the opera) prays before the tomb of Charlemagne. With the announcement that he is elected as Carlo Quinto he declares an amnesty including the eponymous bandit Ernani who had followed him there to murder him as a rival for the love of Elvira. The opera, based on the Victor Hugo play Hernani, portrays Charles as a callous and cynical adventurer whose character is transformed by the election into a responsible and clement ruler.

- In another Verdi opera, Don Carlo, the final scene implies that it is Charles V, now living the last years of his life as a hermit, who rescues his grandson, Don Carlo, from his father Philip II and the Inquisition, by taking Carlo with him to his hermitage at the monastery in Yuste.

Food

- A Flemish legend about Charles being served a beer at the village of Olen, as well as the emperor's lifelong preference of beer above wine, led to the naming of several beer varieties in his honor. The Haacht Brewery of Boortmeerbeek produces Charles Quint, while Het Anker Brewery in Mechelen produces Gouden Carolus, including a Grand Cru of the Emperor, brewed once a year on Charles V's birthday.[64][65][66][67] Grupo Cruzcampo brews Legado De Yuste in honor of Charles and attributes the inspiration to his Flemish origin and his last days at the monastery of Yuste.

- Carlos V is the name of a popular chocolate bar in Mexico. Its tagline is "El Rey de los Chocolates" or "The King of Chocolates" and "Carlos V, El Emperador del Chocolate" or "Charles V, the Emperor of Chocolates."

Television and film

- Charles V is portrayed by Hans Lefebre and is figured prominently in the 1953 film Martin Luther, covering Luther's years from 1505-1530.

- Charles V is portrayed by Torben Liebrecht and is figured prominently in the 2003 film Luther covering the life of Martin Luther up until the Diet of Augsburg.

- Charles V is portrayed in one episode of the Showtime series The Tudors by Sebastian Armesto.

- Charles V is the main subject of the TVE series Carlos, Rey Emperador and is portrayed by Álvaro Cervantes.

Ancestors

See also

Notes

a. ^ Name in other languages:

- ↑ Charles's mother Joanna was still alive at the deaths of her parents, and so was technically the rightful queen of Castile and Aragon. She was mentally insane and held little real power, however, with her father, Ferdinand II of Aragon, and (briefly) her husband and co-ruler Philip (Charles's father), serving as regents. Upon the death of Ferdinand II in 1516, Charles reigned jointly with his mother in the Spanish inheritance, although Joanna remained in confinement.

- ↑ Date of Charles's abdication; on 24 February 1558, the college of electors assembled at Frankfurt accepted the instrument of Charles V's imperial resignation and declared the election of Ferdinand as emperor.[52][53]

- ↑ Edmundson, G. (1922). History of Holland. Cambridge University Press. p. 25.

- ↑ H. Micheal Tarver, ed. (2016). The Spanish Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-61069-421-6.

- ↑ MacCulloch, D. (2 September 2004). Reformation: Europe's House Divided 1490–1700. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-14-192660-5.

- ↑ Armitage, D. (2000). The Ideological Origins of the British Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-521-78978-3.

- ↑ Bérenger, J. (1994-03-07). A History of the Habsburg Empire 1273–1700. Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-582-09010-1.

- ↑ Maltby, William S. (25 March 2002). The Reign of Charles V. European History in Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-333-67768-1.

- ↑ Paul F. State (16 April 2015). Historical Dictionary of Brussels. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-8108-7921-8.

- ↑ Cornelius August Wilkens (1897). "VIII. Juan de Valdés". Spanish Protestants in the Sixteenth Century. William Heinemann. p. 66. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ↑ Charles V, Pierre Chaunu and Michèle Escamilla

- ↑ Burke, "Languages and communities in early modern Europe" p. 28; Holzberger, "The letters of George Santayana" p. 299

- ↑ Charles V, Pierre Chaunu

- ↑ Germany and the Holy Roman Empire, Whaley

- ↑ History of Spain, Joseph Perez

- 1 2 3 Kamen, Henry (2005). Spain, 1469–1714: a society of conflict (3rd ed.). Harlow, United Kingdom: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-78464-6. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017.

- ↑ "Gentenaars Stropdragers". Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ "GILDE van de STROPPENDRAGERS". Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ Martínez Gil, Fernando (2007). "Corte renacentista". La invención de Toledo. Imágenes históricas de una identidad urbana. Almud, ediciones de Castilla-La Mancha. pp. 113–121. ISBN 84-934140-7-7.

- ↑ Martínez Gil, Fernando (1999). "Toledo es Corte (1480-1561)". Historia de Toledo. Azacanes. pp. 259–308. ISBN 84-88480-19-9.

- ↑ "Cortes de los antiguos reinos de León y de Castilla; Manuel Colmeiro (1883)". Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 2012-08-23. ,"XXIII". Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ Estudio documental de la moneda castellana de Carlos I fabricada en los Países Bajos (1517); José María de Francisco Olmos Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Revista General de Información y Documentación 2003, vol 13, núm.2 (Universidad complutense de Madrid), page 137

- ↑ Estudio documental de la moneda castellana de Juana la Loca fabricada en los Países Bajos (1505–1506); José María de Francisco Olmos Archived 14 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Revista General de Información y Documentación 2002, vol 12, núm.2 (Universidad complutense de Madrid), page 299

- ↑ Estudio documental de la moneda castellana de Carlos I fabricada en los Países Bajos (1517); José María de Francisco Olmos, page 138 Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Estudio documental de la moneda castellana de Carlos I fabricada en los Países Bajos (1517); José María de Francisco Olmos, pp. 139–140 Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911 edition.

- ↑ "Cortes de los antiguos reinos de León y de Castilla". Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2016. ; Manuel Colmeiro (1883), chapter XXIV

- ↑ Historia general de España; Modesto Lafuente (1861), pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Fueros, observancias y actos de corte del Reino de Aragón; Santiago Penén y Debesa, Pascual Savall y Dronda, Miguel Clemente (1866) Archived 10 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine., page 64 Archived 10 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Elliot, J.H. Imperial Spain 1469–1716. Penguin Books (New York: 2002), pg. 208.

- ↑ Prescott, William Hickling (1873). History of the Conquest of Mexico, with a Preliminary View of Ancient Mexican Civilization, and the Life of the Conqueror, Hernando Cortes (3rd ed.). Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library. ISBN 1-152-29570-5.

- ↑ Keys, David (August 17, 2018). "Details of horrific first voyages in transatlantic slave trade revealed". The Independent. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ↑ Haskin, Frederic (1913). The Panama Canal. Doubleday, Page & Company.

- ↑ William Maltby, The Reign of Charles V (St. Martin's Press, 2002)

- ↑ Claims that he gained the imperial crown through bribery have been questioned. H.J. Cohn, "Did Bribes Induce the German Electors to Choose Charles V as Emperor in 1519?" German History (2001) 19#1 pp 1–27

- ↑ "Royal Collection - The Knights of the Garter under Henry VIII". www.royalcollection.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2011-12-06. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ Holmes (1993), p. 192

- ↑ Froude (1891), p. 35, pp. 90-91, pp. 96-97 Note: the link goes to page 480, then click the View All option

- ↑ Quoted from: Bryan W. Ball. A Great Expectation. Brill Publishers, 1975. ISBN 90-04-04315-2. Page 142.

- ↑ Sandra Arlinghaus. "Life Span of Suleiman The Magnificent, 1494–1566". Personal.umich.edu. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ In particular, in this Truce of Adrianople (1547) Charles was only referred to as "King of Spain" instead of by his extensive titulature. (see Crowley, p. 89)

- ↑ Stanley Sandler (ed.). Ground Warfare: An International Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ISBN 1-57607-733-0.

- ↑ "A Habsburg-Persian alliance against the Ottomans finally brought a respite from the Turkish threat in the 1540s. This entanglement kept Suleiman tied down on his eastern border, relieving the pressure on Carlos V" in The Indian Ocean in world history? Milo Kearney – 2004 – p.112

- ↑ Palace of Charles V Archived 24 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Alhambra.org

- ↑ Kamen, H. (1997-05-29). Philip of Spain. Yale University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-300-07081-1.

- ↑ Kamen 1997, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-glory/66149817-6f88-4e5f-a09a-81f63a84d145

- ↑ https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-empress-isabel-of-portugal/d4eddf35-c76c-4c11-8f2b-099f7b71d696

- ↑ http://www.brabantensemble.com/discography/thomas-crecquillon-missa-mort-ma-prive-motets-and-chansons/

- ↑ H. Schneble. "German Epilepsy Museum Kork". Epilepsiemuseum.de. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ "Tests confirm old emperor's gout diagnosis." His The Record. 4 August 2006, Nation.

- ↑ Dr. Martyn Rady, University of London, lecture 2000.

- 1 2 3 4 Fernand Braudel (1995). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. University of California Press. pp. 935–936. ISBN 978-0-520-20330-3. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ Setton, K. (1984). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume IV: The Sixteenth Century from Julius III to Pius V. Memoirs. 162. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. p. 716. ISBN 978-0-87169-162-0. ISSN 0065-9738.

- ↑ Robinson, H., ed. (1846). Zurich Letters. Cambridge University Press. p. 182.

- ↑ Joachim Whaley (2012). Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493-1648. OUP Oxford. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-19-873101-6. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ Alonso, Jordi; J. de Zulueta; et al. (August 2006). "The severe gout of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (5): 516–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMon060780. PMID 16885558.

- ↑ William Robertson (1828). History of Charles V. Paris : Baudry, at the foreign library. p. 580. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ de Zulueta, J. (June 2007). "The cause of death of Emperor Charles V". Parassitologia. 49 (1–2): 107–109. PMID 18412053.

- ↑ Kamen 1997, p. 65.

- ↑ "El Escorial History - El Escorial". el-escorial.com. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ↑ https://www.delacuadra.net/escorial/textos/1997c-a-panteo.pdf

- ↑ Tazón, Juan E. (2003). The Life and Times of Thomas Stukeley, 1525–1578. Google Libros. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ Conde de Charolais, título que llevó el emperador hasta su muerte (Miscelánea de artículos publicados en la revista "Hidalguía"). Books.google.es. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ Heymans, Frans (4 June 2007). "Keizer Karel in de literatuur". Overzichten (in Dutch). Literair Gent, an initiative by the Municipal Public Library of Ghent and 'Gent Cultuurstad'. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ↑ "Charles V". Global Beer Network, Santa Barbara, California, U.S.A. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ↑ "Charles Quint Golden Blond". Haacht Brewery. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ↑ "Charles Quint Ruby Red". Haacht Brewery. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ↑ "Beers by Het Anker". Brewery Het Anker. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ↑

- 1 2

- ↑ Urban, William (2003). Tannenberg and After. Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center. p. 191. ISBN 0-929700-25-2.

- 1 2 Wurzbach, Constantin, von, ed. (1861). "Habsburg, Philipp I. der Schöne von Oesterreich" (in German). Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich [Biographical Encyclopedia of the Austrian Empire]. 7. Wikisource. p. 112.

- 1 2 Stephens, Henry Morse (1903). The story of Portugal. G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 139. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4

- 1 2 Kiening, Christian. "Rhétorique de la perte. L'exemple de la mort d'Isabelle de Bourbon (1465)". Médiévales (in French). 13 (27): 15–24. doi:10.3406/medi.1994.1307.

- 1 2

- 1 2

- 1 2

- 1 2 Ortega Gato, Esteban (1999). "Los Enríquez, Almirantes de Castilla" (PDF). Publicaciones de la Institución "Tello Téllez de Meneses" (in Spanish). 70: 42. ISSN 0210-7317.

- 1 2

- 1 2

- 1 2 Downey, Kirstin (November 2015). Isabella: The Warrior Queen. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 9780307742162. Retrieved 2018-07-17.

Bibliography

- Atkins, Sinclair. "Charles V and the Turks," History Today (Dec 1980) 30#12 pp 13–18

- Blockmans, W. P., and Nicolette Mout. The World of Emperor Charles V (2005)

- Brandi, Karl. The emperor Charles V: The growth and destiny of a man and of a world-empire (1939)

- Espinosa, Aurelio. "The Grand Strategy of Charles V (1500–1558): Castile, War, and Dynastic Priority in the Mediterranean," Journal of Early Modern History (2005) 9#3 pp 239–283.

- Espinosa, Aurelio. "The Spanish Reformation: Institutional Reform, Taxation, and the Secularization of Ecclesiastical Properties under Charles V," Sixteenth Century Journal (2006) 37#1 pp 3–24. in JSTOR

- Espinosa, Aurelio. The Empire of the Cities: Emperor Charles V, the Comunero Revolt, and the Transformation of the Spanish System (2008)

- Ferer, Mary Tiffany. Music and Ceremony at the Court of Charles V: The Capilla Flamenca and the Art of Political Promotion. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2012. ISBN 9781843836995

- Froude, James Anthony (1891). The Divorce of Catherine of Aragon. Kessinger Publishing, reprint 2005. ISBN 1417971096. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- Holmes, David L. (1993). A Brief History of the Episcopal Church. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1563380609. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- Howell, Robert B. (2000), "The Low Countries: A Study in Sharply Contrasting Nationalisms", in Barbour, Stephen; Carmichael, Cathie, Language and nationalism in Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 130–50, ISBN 0-19-823671-9

- Kleinschmidt, Harald. Charles V: The World Emperor ISBN 9780750924047

- Saint-Saëns, Alain, ed. Young Charles V. University Press of the South: New Orleans, 2000

Other languages

- (in Italian) Salvatore Agati (2009). Carlo V e la Sicilia. Tra guerre, rivolte, fede e ragion di Stato, Giuseppe Maimone Editore, Catania 2009, ISBN 978-88-7751-287-1

- (in French) D'Amico, Juan Carlos. Charles Quint, Maître du Monde: Entre Mythe et Realite 2004, 290p.

- (in German) Norbert Conrads: Die Abdankung Kaiser Karls V. Abschiedsvorlesung, Universität Stuttgart, 2003 (text)

- (in German) Stephan Diller, Joachim Andraschke, Martin Brecht: Kaiser Karl V. und seine Zeit. Ausstellungskatalog. Universitäts-Verlag, Bamberg 2000, ISBN 3-933463-06-8

- (in German) Alfred Kohler: Karl V. 1500–1558. Eine Biographie. C. H. Beck, München 2001, ISBN 3-406-45359-7

- (in German) Alfred Kohler: Quellen zur Geschichte Karls V. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1990, ISBN 3-534-04820-2

- (in German) Alfred Kohler, Barbara Haider. Christine Ortner (Hrsg): Karl V. 1500–1558. Neue Perspektiven seiner Herrschaft in Europa und Übersee. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien 2002, ISBN 3-7001-3054-6

- (in German) Ernst Schulin: Kaiser Karl V. Geschichte eines übergroßen Wirkungsbereichs. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-17-015695-0

- (in German) Ferdinant Seibt: Karl V. Goldmann, München 1999, ISBN 3-442-75511-5

- (in German) Manuel Fernández Álvarez: Imperator mundi: Karl V. – Kaiser des Heiligen Römischen Reiches Deutscher Nation.. Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-7630-1178-1

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. |

- Genealogy history of Charles V and his ancestors

- The Library of Charles V preserved in the National Library of France

- Luminarium Encyclopedia biography of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

- Answers.com biographies of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

- New Advent biography of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

- (in Italian) Charles V and the Tiburtine Sibyl

- Charles V the Habsburg emperor, video

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor Born: 24 February 1500 Died: 21 September 1558 |

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Philip the Handsome |

Duke of Brabant, Limburg, Lothier and Luxembourg; Count of Artois, Flanders, Hainaut, Holland, Namur and Zeeland; Count Palatine of Burgundy 1506–1555 |

Succeeded by Philip the Prudent |

| Preceded by Joanna the Mad as sole ruler |

King of Naples 1516–1554 with Joanna III (1516–1554) | |

| King of Castile and León, Aragon, Majorca, Valencia and Sicily; Count of Barcelona, Roussillon and Cerdagne 1516–1556 with Joanna (1516–1555) | ||

| Preceded by William the Rich |

Duke of Guelders Count of Zutphen 1543–1555 | |

| Preceded by Maximilian I |

Archduke of Austria Duke of Styria, Carinthia and Carniola Count of Tyrol 1519–1521 |

Succeeded by Ferdinand I |

| King of Germany 1519–1556 | ||

| Holy Roman Emperor King of Italy 1530–1556 | ||

| Spanish royalty | ||

| Preceded by Joanna |

Prince of Asturias 1504–1516 |

Vacant Title next held by Philip (II) |

| Prince of Girona 1516 | ||

.svg.png)