Ainu people

|

Group of Ainu people, photograph c. 1904 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| The official Japanese government estimate is 25,000, although this number has been disputed with unofficial estimates of upwards of 200,000.[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 25,000–200,000 | |

| 109[2]–1,000 | |

| 94–900[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Historically Ainu and other Ainu languages; today, Japanese or Russian[3] | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, Shintoism, Buddhism, Russian Orthodox Christianity, Ainu folk beliefs | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ryukyuans,[4] Jomon, Yamato people, Kamchadal | |

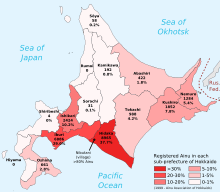

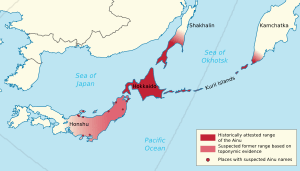

The Ainu or the Aynu (Ainu アィヌ Aynu; Japanese: アイヌ Ainu; Russian: Айны Ajny), in the historical Japanese texts the Ezo (蝦夷), are an indigenous people of Japan (Hokkaido, and formerly northeastern Honshu) and Russia (Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, and formerly the Kamchatka Peninsula).[5]

The official number of the Ainu is 25,000, but unofficially is estimated at 200,000 due to many Ainu having been completely assimilated into Japanese society and, as a result, having no knowledge of their ancestry.

History

Pre-modern

Recent research suggests that Ainu culture originated from a merger of the Jomon, Okhotsk and Satsumon cultures.[6] In 1264, Ainu invaded the land of Nivkh people controlled by the Yuan Dynasty of Mongolia, resulting in battles between Ainu and the Chinese.[7] Active contact between the Wajin (the ethnically Japanese) and the Ainu of Ezochi (now known as Hokkaido) began in the 13th century.[8] The Ainu formed a society of hunter-gatherers, surviving mainly by hunting and fishing. They followed a religion which was based on natural phenomena.[9]

During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), the disputes between the Japanese and Ainu developed into a war. Takeda Nobuhiro killed the Ainu leader, Koshamain. Many Ainu were subject to Japanese rule which led to a violent Ainu revolt such as Koshamain's Revolt (ja:コシャマインの戦い) in 1456.

.jpg)

During the Edo period (1601–1868) the Ainu, who controlled the northern island which is now named Hokkaido, became increasingly involved in trade with the Japanese who controlled the southern portion of the island. The Tokugawa bakufu (feudal government) granted the Matsumae clan exclusive rights to trade with the Ainu in the northern part of the island. Later, the Matsumae began to lease out trading rights to Japanese merchants, and contact between Japanese and Ainu became more extensive. Throughout this period the Ainu became increasingly dependent on goods imported by the Japanese, and were suffering from epidemic diseases such as smallpox.[10] Although the increased contact created by the trade between the Japanese and the Ainu contributed to increased mutual understanding, it also led to conflict which occasionally intensified into violent Ainu revolts. The most important was Shakushain's Revolt (1669–1672), an Ainu rebellion against Japanese authority. Another large-scale revolt by Ainu against Japanese rule was the Menashi-Kunashir Battle in 1789.

Meiji Restoration and later

In the 18th century, there were 80,000 Ainu.[11] In 1868, there were about 15,000 Ainu in Hokkaido, 2000 in Sakhalin and around 100 in the Kuril islands.[12]

The beginning of the Meiji Restoration in 1868 proved a turning point for Ainu culture. The Japanese government introduced a variety of social, political, and economic reforms in hope of modernizing the country in the Western style. One innovation involved the annexation of Hokkaido. Sjöberg quotes Baba's (1980) account of the Japanese government's reasoning:[10]

… The development of Japan's large northern island had several objectives: First, it was seen as a means to defend Japan from a rapidly developing and expansionist Russia. Second … it offered a solution to the unemployment for the former samurai class … Finally, development promised to yield the needed natural resources for a growing capitalist economy.[13]

In 1899, the Japanese government passed an act labelling the Ainu as "former aborigines", with the idea they would assimilate—this resulted in the Japanese government taking the land where the Ainu people lived and placing it from then on under Japanese control.[14] Also at this time, the Ainu were granted automatic Japanese citizenship, effectively denying them the status of an indigenous group.

The Ainu were becoming increasingly marginalized on their own land—over a period of only 36 years, the Ainu went from being a relatively isolated group of people to having their land, language, religion and customs assimilated into those of the Japanese.[15] In addition to this, the land the Ainu lived on was distributed to the Wajin who had decided to move to Hokkaido, encouraged by the Japanese government of the Meiji era to take advantage of the island's abundant natural resources, and to create and maintain farms in the model of Western industrial agriculture. While at the time, the process was openly referred to as colonization ("takushoku" 拓殖), the notion was later reframed by Japanese elites to the currently common usage "kaitaku" (開拓), which instead conveys a sense of opening up or reclamation of the Ainu lands.[16] As well as this, factories such as flour mills, beer breweries and mining practices resulted in the creation of infrastructure such as roads and railway lines, during a development period that lasted until 1904.[17] During this time, the Ainu were forced to learn Japanese, required to adopt Japanese names, and ordered to cease religious practices such as animal sacrifice and the custom of tattooing.[18]

_with_seated_young_boy_and_man_holding_a_baby_in_the_Department_of_Anthropology_exhibit_at_the_1904_World's_Fair.jpg)

The 1899 act mentioned above was replaced in 1997—until then the government had stated there were no ethnic minority groups.[6] It was not until June 6, 2008, that Japan formally recognised the Ainu as an indigenous group (see Official Recognition, below).[6]

The vast majority of these Wajin men are believed to have compelled Ainu women into partnering with them as local wives.[19] Intermarriage between Japanese and Ainu was actively promoted by the Ainu to lessen the chances of discrimination against their offspring. As a result, many Ainu are indistinguishable from their Japanese neighbors, but some Ainu-Japanese are interested in traditional Ainu culture. For example, Oki, born as a child of an Ainu father and a Japanese mother, became a musician who plays the traditional Ainu instrument tonkori.[20] There are also many small towns in the southeastern or Hidaka region where ethnic Ainu live such as in Nibutani (Ainu: Niputay). Many live in Sambutsu especially, on the eastern coast. In 1966 the number of "pure" Ainu was about 300.[21]

Their most widely known ethnonym is derived from the word ainu, which means "human" (particularly as opposed to kamui, divine beings), basically neither ethnicity nor the name of a race, in the Hokkaido dialects of the Ainu language. Ainu is the word Ainu identify themselves as from their first male ancestor Aioina; Ainu means human in the Ainu language. Ainu also identify themselves as Utari (comrade in the Ainu language). Official documents use both names.

Official recognition in Japan

On June 6, 2008, the Japanese Diet passed a bipartisan, non-binding resolution calling upon the government to recognize the Ainu people as indigenous to Japan, and urging an end to discrimination against the group. The resolution recognised the Ainu people as "an indigenous people with a distinct language, religion and culture". The government immediately followed with a statement acknowledging its recognition, stating, "The government would like to solemnly accept the historical fact that many Ainu were discriminated against and forced into poverty with the advancement of modernization, despite being legally equal to (Japanese) people."[15][22]

Official recognition in Russia

As a result of the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1875), the Kuril Islands – along with their Ainu inhabitants – came under Japanese administration. A total of 83 North Kuril Ainu arrived in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on September 18, 1877, after they decided to remain under Russian rule. They refused the offer by Russian officials to move to new reservations in the Commander Islands. Finally a deal was reached in 1881 and the Ainu decided to settle in the village of Yavin. In March 1881, the group left Petropavlovsk and started the journey towards Yavin on foot. Four months later they arrived at their new homes. Another village, Golygino, was founded later. Under Soviet rule, both the villages were forced to disband and residents were moved to the Russian-dominated Zaporozhye rural settlement in Ust-Bolsheretsky Raion.[23] As a result of intermarriage, the three ethnic groups assimilated to form the Kamchadal community. In 1953, K. Omelchenko, the minister for the protection of military and state secrets in the USSR, banned the press from publishing any more information on the Ainu living in the USSR. This order was revoked after two decades.[24]

As of 2015, the North Kuril Ainu of Zaporozhye form the largest Ainu subgroup in Russia. The Nakamura clan (South Kuril Ainu on their paternal side), the smallest group, numbers just six people residing in Petropavlovsk. On Sakhalin island, a few dozen people identify themselves as Sakhalin Ainu, but many more with partial Ainu ancestry do not acknowledge it. Most of the 888 Japanese people living in Russia (2010 Census) are of mixed Japanese-Ainu ancestry, although they do not acknowledge it (full Japanese ancestry gives them the right of visa-free entry to Japan.[25]) Similarly, no one identifies themselves as Amur Valley Ainu, although people with partial descent live in Khabarovsk. There is no evidence of living descendants of the Kamchatka Ainu.

In the 2010 Census of Russia, close to 100 people tried to register themselves as ethnic Ainu in the village, but the governing council of Kamchatka Krai rejected their claim and enrolled them as ethnic Kamchadal.[24][26] In 2011, the leader of the Ainu community in Kamchatka, Alexei Vladimirovich Nakamura, requested that Vladimir Ilyukhin (Governor of Kamchatka) and Boris Nevzorov (Chairman of the State Duma) include the Ainu in the central list of the Indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East. This request was also turned down.[27]

Ethnic Ainu living in Sakhalin Oblast and Khabarovsk Krai are not organized politically. According to Alexei Nakamura, as of 2012 only 205 Ainu live in Russia (up from just 12 people who self-identified as Ainu in 2008) and they along with the Kurile Kamchadals (Itelmen of Kuril islands) are fighting for official recognition.[28][29] Since the Ainu are not recognized in the official list of the peoples living in Russia, they are counted as people without nationality or as ethnic Russians or Kamchadal.[30]

The Ainu have emphasized that they were the natives of the Kuril islands and that the Japanese and Russians were both invaders.[31] In 2004, the small Ainu community living in Russia in Kamchatka Krai wrote a letter to Vladimir Putin, urging him to reconsider any move to award the Southern Kuril Islands to Japan. In the letter they blamed the Japanese, the Tsarist Russians and the Soviets for crimes against the Ainu such as killings and assimilation, and also urged him to recognize the Japanese genocide against the Ainu people—which was turned down by Putin.[32]

As of 2012 both the Kurile Ainu and Kurile Kamchadal ethnic groups lack the fishing and hunting rights which the Russian government grants to the indigenous tribal communities of the far north.[33][34]

Origins

The Ainu have often been considered to descend from the Jōmon people, who lived in Japan from the Jōmon period[36] (c. 14,000 to 300 BCE). One of their Yukar Upopo, or legends, tells that "[t]he Ainu lived in this place a hundred thousand years before the Children of the Sun came".[13]

Recent research suggests that the historical Ainu culture originated in a merger of the Okhotsk culture with the Satsumon, one of the ancient archaeological cultures that are considered to have derived from the Jōmon-period cultures of the Japanese archipelago.[37][38] The Ainu economy was based on farming, as well as on hunting, fishing and gathering.[39]

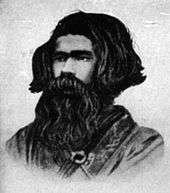

Full-blooded Ainu, compared to people of Yamato descent, often have lighter skin and more body hair.[40] Many early investigators proposed a Caucasian ancestry,[41] although recent DNA tests have not shown any genetic similarity with modern Europeans. Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza places the Ainu in his "Northeast and East Asian" genetic cluster.[42]

Anthropologist Joseph Powell of the University of New Mexico wrote "...we follow Brace and Hunt (1990) and Turner (1990) in viewing the Ainu as a southeast Asian population derived from early Jomon peoples of Japan, who have their closest biological affinity with south Asians rather than western Eurasia peoples".[43]

A autosomal DNA research in 2017 resulted in grouping the Ainu and other Jōmon remnants with northeastern Asians.[44]

Mark J. Hudson, Professor of Anthropology at Nishikyushu University, Kanzaki, Saga, Japan, has stated that Japan was settled by a "Proto-Mongoloid" population in the Pleistocene who became the Jōmon and that their features can be seen in the Ainu and Okinawan people.[45]

In 1893, anthropologist Arnold Henry Savage Landor described the Ainu as having deep-set eyes and an eye shape typical of Europeans, with a large and prominent browridge, large ears, hairy and prone to baldness, slightly hook nose with large and broad nostrils, prominent cheek-bones and a medium mouth.[46]

Omoto has also shown that the Ainu are far more related to other East Asian groups (previously mentioned as 'Mongoloid') than to any Caucasian groups, on the basis of fingerprints and dental morphology.[47]

Proto-Mongoloids

Theodore G. Schurr of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania said that Mongoloid traits emerged from Transbaikalia, central and eastern regions of Mongolia, and several regions of Northern China. Schurr said that studies of cranio-facial variation in Mongolia suggest that the region of modern-day Mongolians is the origin of the Mongoloid racial type".[48]

Dr. Rukang Wu (Chinese: 吴汝康) of the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Academia Sinica, China, said that the remains of Liukiang human fossils were an early type of evolving Mongoloid that indicated South China was the birthplace where the Mongoloid race originated.[49]

Dr. Marta Mirazón Lahr of the Department of Biological Anthropology at Cambridge University said there are two hypotheses on the origin of Mongoloids. Lahr said that one hypothesis is that Mongoloids originated in north Asia due to the regional continuity in this region and this population conforming best to the standard Mongoloid features. Lahr said that the other hypothesis is that Mongoloids originate from Southeast Asian populations that expanded from Africa to Southeast Asia during the first half of the Upper Pleistocene and then traveled to Australia-Melanesia and East Asia. Lahr said that the morphology of the Paleoindian is consistent with the proto-Mongoloid definition.[50]

Hisao Baba and Shuichiro Narasaki of the Department of Anthropology at the National Science Museum, in Tokyo, Japan, said that it is broadly accepted that Zhoukoudian Upper Cave Man and maybe Liujian Man were "so-called proto-Mongoloids" who did not have a completely developed Mongoloid complex.

Turner found remains of Jōmon people of Japan to belong to a Sundadont pattern similar to the Southern Mongoloid living populations of Taiwanese aborigines, Filipinos, Vietnamese, Indonesians, Thais, Borneans, Laotians, and Malaysians. A recreation of a map made by William W. Howells, professor of anthropology at Harvard University, shows in the shaded the remnants and populations of non-Mongoloid people, appearing as N (Negrito) or A (Australoids of Wallacea, Melanesia and Australia). The latter peoples comprise the present aboriginals of Australia and Melanesia, as shown; the interest here is their presence and remnants. Sundadonts comprise Southeast Asians and peoples from northern Japan and the Amur area. Sinodonts comprise the East Asian populations from Korea, Japan, China, Mongolia and Siberia.

Ainu men have abundant wavy hair and often have long beards.[51] The book of Ainu Life and Legends by author Kyōsuke Kindaichi (published by the Japanese Tourist Board in 1942) contains a physical description of Ainu:

Many have wavy hair, but some straight black hair. Very few of them have wavy brownish hair. Their skins are generally reported to be light brown. But this is due to the fact that they labor on the sea and in briny winds all day. Old people who have long desisted from their outdoor work are often found to be as white as western men. The Ainu have broad faces, beetling eyebrows, and large sunken eyes, which are generally horizontal and of the so-called European type. Eyes of the Mongolian type are hardly found among them.

Genetics

._Auguste_Wahlen._Moeurs%2C_usages_et_costumes_de_tous_les_peuples_du_monde._1843.jpg)

Genetic testing has shown that the Ainu belong mainly to Y-haplogroup D-M55.[52] Y-DNA haplogroup D1b is found throughout the Japanese Archipelago, but with very high frequencies among the Ainu of Hokkaido in the far north, and to a lesser extent among the Rykyuans in the Ryukyu Islands of the far south. The only places outside Japan in which Y-haplogroup D is common are parts of Central Asia, Tibet in China and the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean.[53]

A study by Tajima et al. (2004) found two out of a sample of sixteen (or 12.5%) Ainu men to belong to Haplogroup C-M217, which is the most common Y-chromosome haplogroup among the indigenous populations of Siberia and Mongolia.[52] Hammer et al. (2006) tested a sample of four Ainu men and found that one of them belonged to haplogroup C-M217.[54] Some researchers have speculated that this minority of Haplogroup C-M217 carriers among the Ainu may reflect a certain degree of unidirectional genetic influence from the Nivkhs, a traditionally nomadic people of northern Sakhalin and the adjacent mainland, with whom the Ainu have long-standing cultural interactions.[52]

Based on analysis of one sample of 51 modern Ainus, their mtDNA lineages consist mainly of haplogroup Y (11/51 = 21.6% according to Tanaka et al. 2004, or 10/51 = 19.6% according to Adachi et al. 2009, who have cited Tajima et al. 2004), haplogroup D (9/51 = 17.6%, particularly D4(xD1)), haplogroup M7a (8/51 = 15.7%), and haplogroup G1 (8/51 = 15.7%).[52][55][56] Other mtDNA haplogroups detected in this sample include A (2/51), M7b2 (2/51), N9b (1/51), B4f (1/51), F1b (1/51), and M9a (1/51). Most of the remaining individuals in this sample have been classified definitively only as belonging to macro-haplogroup M.[55] According to Sato et al. (2009), who have studied the mtDNA of the same sample of modern Ainus (n=51), the major haplogroups of the Ainu are N9 (14/51 = 27.5%, including 10/51 Y and 4/51 N9(xY)), D (12/51 = 23.5%, including 8/51 D(xD5) and 4/51 D5), M7 (10/51 = 19.6%), and G (10/51 = 19.6%, including 8/51 G1 and 2/51 G2); the minor haplogroups are A (2/51), B (1/51), F (1/51), and M(xM7, M8, CZ, D, G) (1/51).[57] Studies published in 2004 and 2007 show the combined frequency of M7a and N9b were observed in Jomons and which are believed by some to be Jomon maternal contribution at 28% in Okinawans (7/50 M7a1, 6/50 M7a(xM7a1), 1/50 N9b), 17.6% in Ainus (8/51 M7a(xM7a1), 1/51 N9b), and from 10% (97/1312 M7a(xM7a1), 1/1312 M7a1, 28/1312 N9b) to 17% (15/100 M7a1, 2/100 M7a(xM7a1)) in mainstream Japanese.[58][59]

A recent reevaluation of cranial traits suggests that the Ainu resemble the Okhotsk more than they do the Jōmon.[60] This agrees with the references to the Ainu as a merger of Okhotsk and Satsumon referenced above. A recent genetic study has revealed that the closest genetic relatives of the Ainu are the Ryukyuan people, followed by the Yamato people and Nivkh.[61]

A genetic research from 2016, comparing East Asians, Siberians and Native Americans, showed that the Ainu (and Jomon samples) are compared to all other Asians most closely related to Northeast Asian Siberian populations and some northern Native Americans. The study did not find any genetic relations between Tibetans, Andamanese and Ainu, suggesting the already existing view that y-DNA Haplogroups do not show close relationships at all.[62]

Language

Today, it is estimated that fewer than 100 speakers of the language remain,[63] while other research places the number at fewer than 15 speakers. The language has been classified as "endangered".[64] As a result of this the study of the Ainu language is limited and is based largely on historical research.

Although there have been attempts to show that the Ainu language and the Japanese language are related, modern scholars have rejected that the relationship goes beyond contact, such as the mutual borrowing of words between Japanese and Ainu. No attempt to show a relationship with Ainu to any other language has gained wide acceptance, and Ainu is currently considered to be a language isolate.[65]

Words used as prepositions in English (such as to, from, by, in, and at) are postpositional in Ainu; they come after the word that they modify. A single sentence in Ainu can be made up of many added or agglutinated sounds or affixes that represent nouns or ideas.

The Ainu language has had no system of writing, and has historically been transliterated by the Japanese kana or Russian Cyrillic. Today, it is typically written in either katakana or Latin alphabet. The unwieldy nature of the Japanese kana with its inability to accurately represent coda consonants has contributed to the degradation of the original Ainu. For example, some words, such as Kor (meaning "to hold"), are now pronounced with a paragoge, as in Koro.

Many of the Ainu dialects, even from one end of Hokkaido to the other, were not mutually intelligible; however, the classic Ainu language of the Yukar, or Ainu epic stories, was understood by all. Without a writing system, the Ainu were masters of narration, with the Yukar and other forms of narration such as the Uepeker (Uwepeker) tales, being committed to memory and related at gatherings, often lasting many hours or even days.[66]

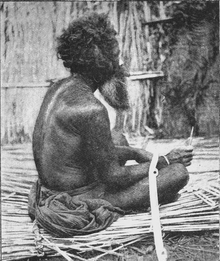

Culture

Traditional Ainu culture was quite different from Japanese culture. Never shaving after a certain age, the men had full beards and moustaches. Men and women alike cut their hair level with the shoulders at the sides of the head, trimmed semicircularly behind. The women tattooed their mouths, and sometimes the forearms. The mouth tattoos were started at a young age with a small spot on the upper lip, gradually increasing with size. The soot deposited on a pot hung over a fire of birch bark was used for colour. Their traditional dress was a robe spun from the inner bark of the elm tree, called attusi or attush. Various styles were made, and consisted generally of a simple short robe with straight sleeves, which was folded around the body, and tied with a band about the waist. The sleeves ended at the wrist or forearm and the length generally was to the calves. Women also wore an undergarment of Japanese cloth.[67]

Modern craftswomen weave and embroider traditional garments that command very high prices. In winter the skins of animals were worn, with leggings of deerskin and in Sakhalin, boots were made from the skin of dogs or salmon.[68] Ainu culture considers earrings, traditionally made from grapevines, to be gender neutral. Women also wear a beaded necklace called a tamasay.[67]

Their traditional cuisine consists of the flesh of bear, fox, wolf, badger, ox, or horse, as well as fish, fowl, millet, vegetables, herbs, and roots. They never ate raw fish or flesh; it was always boiled or roasted.[67]

Their traditional habitations were reed-thatched huts, the largest 20 ft (6 m) square, without partitions and having a fireplace in the center. There was no chimney, only a hole at the angle of the roof; there was one window on the eastern side and there were two doors. The house of the village head was used as a public meeting place when one was needed.[67] Another kind of traditional Ainu house was called chise.[69]

Instead of using furniture, they sat on the floor, which was covered with two layers of mats, one of rush, the other of a water plant with long sword shaped leaves (Iris pseudacorus); and for beds they spread planks, hanging mats around them on poles, and employing skins for coverlets. The men used chopsticks when eating; the women had wooden spoons.[67] Ainu cuisine is not commonly eaten outside Ainu communities; there are only a few Ainu-run restaurants in Japan, all located in Tokyo or Hokkaido, serving primarily Japanese fare.

The functions of judgeship were not entrusted to chiefs; an indefinite number of a community's members sat in judgment upon its criminals. Capital punishment did not exist, nor did the community resort to imprisonment. Beating was considered a sufficient and final penalty. However, in the case of murder, the nose and ears of the culprit were cut off or the tendons of his feet severed.[67]

Hunting

The Ainu hunted from late autumn to early summer.[70] The reasons for this were, among others, that in late autumn, plant gathering, salmon fishing and other activities of securing food came to an end, and hunters readily found game in fields and mountains in which plants had withered.

A village possessed a hunting ground of its own or several villages used a joint hunting territory (iwor).[71] Heavy penalties were imposed on any outsiders trespassing on such hunting grounds or joint hunting territory.

The Ainu hunted bear, Ezo deer (a subspecies of sika deer), rabbit, fox, raccoon dog, and other animals.[72] Ezo deer were a particularly important food resource for the Ainu, as were salmon.[73] They also hunted sea eagles such as white-tailed sea eagles, raven and other birds.[74] The Ainu hunted eagles to obtain their tail feathers, which they used in trade with the Japanese.[75]

The Ainu hunted with arrows and spears with poison-coated points.[76] They obtained the poison, called surku, from the roots and stalks of aconites.[77] The recipe for this poison was a household secret that differed from family to family. They enhanced the poison with mixtures of roots and stalks of dog's bane, boiled juice of Mekuragumo, Matsumomushi, tobacco and other ingredients. They also used stingray stingers or skin covering stingers.[78]

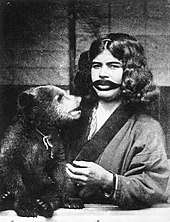

They hunted in groups with dogs.[79] Before the Ainu went hunting, for animals like bear in particular, they prayed to the god of fire and the house guardian god to convey their wishes for a large catch, and safe hunting to the god of mountains.[80]

The Ainu usually hunted bear during the time of the spring thaw. At that time, bears were weak because they had not fed at all during long hibernation. Ainu hunters caught hibernating bears or bears that had just left hibernation dens.[81] When they hunted bear in summer, they used a spring trap loaded with an arrow, called an amappo.[81] The Ainu usually used arrows to hunt deer.[82] Also, they drove deer into a river or sea and shot them with arrows. For a large catch, a whole village would drive a herd of deer off a cliff and club them to death.[83]

Ornaments

Men wore a crown called sapanpe for important ceremonies. Sapanpe was made from wood fibre with bundles of partially shaved wood. This crown had wooden figures of animal gods and other ornaments on its centre.[84] Men carried an emush (ceremonial sword)[85] secured by an emush at strap to their shoulders.[86]

Women wore matanpushi, embroidered headbands, and ninkari, earrings. Ninkari was a metal ring with a ball. Women wore it through a hole in the ear. Matanpushi and ninkari were originally worn by men. However, women wear them now. Furthermore, aprons called maidari now are a part of women's formal clothes. However, some old documents say that men wore maidari.[84] Women sometimes wore a bracelet called tekunkani.[87]

Women wore a necklace called rektunpe, a long, narrow strip of cloth with metal plaques.[84] They wore a necklace that reached the breast called a tamasay or shitoki, usually made from glass balls. Some glass balls came from trade with the Asian continent. The Ainu also obtained glass balls secretly made by the Matsumae clan.[88]

Housing

A village is called a kotan in the Ainu language. Kotan were located in river basins and seashores where food was readily available, particularly in the basins of rivers through which salmon went upstream. A village consisted basically of a paternal clan. The average number of families was four to seven, rarely reaching more than ten. In the early modern times, the Ainu people were forced to labor at the fishing grounds of the Japanese. Ainu kotan were also forced to move near fishing grounds so that the Japanese could secure a labor force. When the Japanese moved to other fishing grounds, Ainu kotan were also forced to accompany them. As a result, the traditional kotan disappeared and large villages of several dozen families were formed around the fishing grounds.

Cise or cisey (houses) in a kotan were made of cogon grasses, bamboo grass, barks, etc. The length lay east to west or parallel to a river. A house was about seven meters by five with an entrance at the west end that also served as a storeroom. The house had three windows, including the "rorun-puyar," a window located on the side facing the entrance (at the east side), through which gods entered and left and ceremonial tools were taken in and out. The Ainu have regarded this window as sacred and have been told never to look in through it. A house had a fireplace near the entrance. The husband and wife sat on the fireplace's left side (called shiso) . Children and guests sat facing them on the fireplace's right side (called harkiso). The house had a platform for valuables called iyoykir behind the shiso. The Ainu placed sintoko (hokai) and ikayop (quivers) there.

Outbuildings included separate lavatories for men called ashinru and for women called menokoru, a pu (storehouse) for food, a "heper set" (cage for young bear), and drying-racks for fish and wild plants. An altar (nusasan) faced the east side of the house (rorunpuyar). The Ainu held such ceremonies there as Iyomante, a ceremony to send the spirit of a bear to the gods.

Ainu houses (from Popular Science Monthly Volume 33, 1888)

Ainu houses (from Popular Science Monthly Volume 33, 1888) Plan of an Ainu house

Plan of an Ainu house The family would gather around the fireplace.

The family would gather around the fireplace. Interior of the house of Ainu - Saru River basin

Interior of the house of Ainu - Saru River basin

Traditions

The Ainu people had various types of marriage. A child was promised in marriage by arrangement between his or her parents and the parents of his or her betrothed or by a go-between. When the betrothed reached a marriageable age, they were told who their spouse was to be. There were also marriages based on mutual consent of both sexes.[89] In some areas, when a daughter reached a marriageable age, her parents let her live in a small room called tunpu annexed to the southern wall of her house.[90] The parents chose her spouse from men who visited her.

The age of marriage was 17 to 18 years of age for men and 15 to 16 years of age for women,[84] who were tattooed. At these ages, both sexes were regarded as adults.[91]

When a man proposed to a woman, he visited her house, ate half a full bowl of rice handed to him by her, and returned the rest to her. If the woman ate the rest, she accepted his proposal. If she did not and put it beside her, she rejected his proposal.[84] When a man became engaged to a woman or they learned that their engagement had been arranged, they exchanged gifts. He sent her a small engraved knife, a workbox, a spool, and other gifts. She sent him embroidered clothes, coverings for the back of the hand, leggings and other handmade clothes.[92] According to some books, many yomeiri marriages, in which a bride went to the house of a bridegroom with her belongings to become a member of his family, were conducted in the old days.

For a yomeiri marriage, a man and his father would bring betrothal gifts to the house of a woman, including a sword, a treasured sword, an ornamental quiver, a sword guard, and a woven basket (hokai). If the man and woman agreed to marry, the man and his father would bring her to their house or the man would stay at her house for a while and then bring her to his house. At the wedding ceremony, participants prayed to the god of fire. Bride and bridegroom respectively ate half of the rice served in a bowl, and other participants were entertained.[93]

The worn-out fabric of old clothing was used for baby clothes because soft cloth was good for the skin of babies and worn-out material protected babies from gods of illness and demons due to these gods' abhorrence of dirty things. Before a baby was breast-fed, he/she was given a decoction of the endodermis of alder and the roots of butterburs to discharge impurities.[94] Children were raised almost naked until about the ages of four to five. Even when they wore clothes, they did not wear belts and left the front of their clothes open. Subsequently, they wore bark clothes without patterns, such as attush, until coming of age.

Newborn babies were named ayay (a baby's crying),[95] shipo, poyshi (small excrement), and shion (old excrement). Children were called by these "temporary" names until the ages of two to three. They were not given permanent names when they were born.[95] Their tentative names had a portion meaning "excrement" or "old things" to ward off the demon of ill-health. Some children were named based on their behaviour or habits. Other children were named after impressive events or after parents' wishes for the future of the children. When children were named, they were never given the same names as others.[96]

Men wore loincloths and had their hair dressed properly for the first time at age 15–16. Women were also considered adults at the age of 15–16. They wore underclothes called mour[97] and had their hair dressed properly and wound waistcloths called raunkut and ponkut around their bodies.[98] When women reached age 12–13, the lips, hands and arms were tattooed. When they reached age 15–16, their tattoos were completed. Thus were they qualified for marriage.[91]

Religion

The Ainu are traditionally animists, believing that everything in nature has a kamuy (spirit or god) on the inside. The most important include Kamuy Fuchi, goddess of the hearth, Kim-un Kamuy, god of bears and mountains, and Repun Kamuy, god of the sea, fishing, and marine animals.

The Ainu have no priests by profession; instead the village chief performs whatever religious ceremonies are necessary. Ceremonies are confined to making libations of sake, saying prayers, and offering willow sticks with wooden shavings attached to them.[67] These sticks are called inaw (singular) and nusa (plural).

They are placed on an altar used to "send back" the spirits of killed animals. Ainu ceremonies for sending back bears are called Iyomante. The Ainu people give thanks to the gods before eating and pray to the deity of fire in time of sickness. They believe their spirits are immortal, and that their spirits will be rewarded hereafter by ascending to kamuy mosir (Land of the Gods).[67]

The Ainu are part of a larger collective of indigenous people who practice "arctolatry" or bear worship. The Ainu believe the bear is very special because they think the bear is Kim-un Kamuy's way of delivering the gift of bear hide and meat to humans.

John Batchelor reported that the Ainu view the world as being a spherical ocean on which float many islands, a view based on the fact that the sun rises in the east and sets in the west. He wrote that they believe the world rests on the back of a large fish, which when it moves causes earthquakes.[99]

Ainu assimilated into mainstream Japanese society have adopted Buddhism and Shinto, while some northern Ainu are members of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Institutions

Most Hokkaido Ainu and some other Ainu are members of an umbrella group called the Hokkaido Utari Association. It was originally controlled by the government to speed Ainu assimilation and integration into the Japanese nation-state. It now is run exclusively by Ainu and operates mostly independently of the government.

Other key institutions include The Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture (FRPAC), set up by the Japanese government after enactment of the Ainu Culture Law in 1997, the Hokkaido University Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies[100] established in 2007, as well as museums and cultural centers. Ainu people living in Tokyo have also developed a vibrant political and cultural community.[101][102]

Status

Litigation

On March 27, 1997, the Sapporo District Court decided a landmark case that, for the first time in Japanese history, recognized the right of the Ainu people to enjoy their distinct culture and traditions. The case arose because of a 1978 government plan to build two dams in the Saru River watershed in southern Hokkaido. The dams were part of a series of development projects under the Second National Development Plan that were intended to industrialize the north of Japan.[103] The planned location for one of the dams was across the valley floor close to Nibutani village,[104] the home of a large community of Ainu people and an important center of Ainu culture and history.[105] In the early 1980s when the government commenced construction on the dam, two Ainu landowners refused to agree to the expropriation of their land. These landowners were Kaizawa Tadashi and Kayano Shigeru—well-known and important leaders in the Ainu community.[106] After Kaizawa and Kayano declined to sell their land, the Hokkaido Development Bureau applied for and was subsequently granted a Project Authorization, which required the men to vacate their land. When their appeal of the Authorization was denied, Kayano and Kaizawa's son Koichii (Kaizawa died in 1992), filed suit against the Hokkaido Development Bureau.

The final decision denied the relief sought by the plaintiffs for pragmatic reasons—the dam was already standing—but the decision was nonetheless heralded as a landmark victory for the Ainu people. In short, nearly all of the plaintiffs' claims were recognized. Moreover, the decision marked the first time Japanese case law acknowledged the Ainu as an indigenous people and contemplated the responsibility of the Japanese nation to the indigenous people within its borders.[104]:442 The decision included broad fact-finding that underscored the long history of the oppression of the Ainu people by Japan's majority, referred to as Wajin in the case and discussions about the case.[104][107] The legal roots of the decision can be found in Article 13 of Japan's Constitution, which protects the rights of the individual, and in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[108][109] The decision was issued on March 27, 1997, and because of the broad implications for Ainu rights, the plaintiffs decided not to appeal the decision, which became final two weeks later. After the decision was issued, on May 8, 1997, the Diet passed the Ainu Culture Law and repealed the Ainu Protection Act—the 1899 law that had been the vehicle of Ainu oppression for almost one hundred years.[110][111] While the Ainu Culture Law has been widely criticized for its shortcomings, the shift that it represents in Japan's view of the Ainu people is a testament to the importance of the Nibutani decision. In 2007 the 'Cultural Landscape along the Sarugawa River resulting from Ainu Tradition and Modern Settlement' was designated an Important Cultural Landscape.[112] A later action seeking restoration of Ainu assets held in trust by the Japanese Government was dismissed in 2008.[113]

Governmental advisory boards

Much national policy in Japan has been developed out of the action of governmental advisory boards, known as shingikai (審議会) in Japanese. One such committee operated in the late 1990s,[114] and its work resulted in the 1997 Ainu Culture Law.[110] This panel's circumstances were criticized for including not even a single Ainu person among its members.[114]

More recently, a panel was established in 2006, which notably was the first time an Ainu person was included. It completed its work in 2008 issuing a major report that included an extensive historical record and called for substantial government policy changes towards the Ainu.

Formation of Ainu political party

The Ainu Party (アイヌ民族党 Ainu minzoku tō) was founded on January 21, 2012,[115] after a group of Ainu activists in Hokkaido announced the formation of a political party for the Ainu on October 30, 2011. The Ainu Association of Hokkaido reported that Kayano Shiro, the son of the former Ainu leader Kayano Shigeru, will head the party. Their aim is to contribute to the realization of a multicultural and multiethnic society in Japan, along with rights for the Ainu.[116][117]

Standard of living

The Ainu have historically suffered from economic and social discrimination throughout Japan that continues to this day. The Japanese Government as well as people since contact with the Ainu, have in large part regarded them as a dirty, backwards and a primitive people.[118] The majority of Ainu were forced to be petty laborers during the Meiji Restoration, which saw the introduction of Hokkaido into the Japanese Empire and the privatization of traditional Ainu lands.[119] The Japanese government during the 19th and 20th centuries denied the rights of the Ainu to their traditional cultural practices, most notably the right to speak their language, as well as their right to hunt and gather.[120] These policies were designed to fully integrate the Ainu into Japanese society with the cost of erasing Ainu culture and identity. The Ainu's position as manual laborers and their forced integration into larger Japanese society have led to discriminatory practices by the Japanese government that can still be felt today.[121] This discrimination and negative stereotypes assigned to the Ainu have manifested in the Ainu's lower levels of education, income levels and participation in the economy as compared to their ethnically Japanese counterparts. The Ainu community in Hokkaido in 1993 received welfare payments at a 2.3 times higher rate, had a 8.9% lower enrollment rate from junior high school to high school and a 15.7% lower enrollment into college from high school than that of Hokkaido as a whole.[119] The Japanese government has been lobbied by activists to research the Ainu's standard of living nationwide due to this noticeable and growing gap. The Japanese government will provide ¥7 million beginning in 2015, to conduct surveys nationwide on this matter.[122]

Subgroups

- Hokkaido Ainu (the predominant community of Ainu in the world today): A Japanese census in 1916 returned 13,557 pure-blooded Ainu in addition to 4,550 multiracial individuals.[123]

- Tokyo Ainu (a modern age migration of Hokkaido Ainu highlighted in a documentary film released in 2010)[101]

- Tohoku Ainu (from Honshū, no officially acknowledged population exists): Forty-three Ainu households scattered throughout the Tohoku region were reported during the 17th century.[124] There are people who consider themselves descendants of Shimokita Ainu on the Shimokita Peninsula, while the people on the Tsugaru Peninsula are generally considered Yamato but may be descendants of Tsugaru Ainu after cultural assimilation.[125]

- Sakhalin Ainu: Pure-blooded individuals may be surviving in Hokkaido. From both Northern and Southern Sakhalin, a total of 841 Ainu were relocated to Hokkaido in 1875 by Japan. Only a few in remote interior areas remained, as the island was turned over to Russia. Even when Japan was granted Southern Sakhalin in 1905, only a handful returned. The Japanese census of 1905 counted only 120 Sakhalin Ainu (down from 841 in 1875, 93 in Karafuto and 27 in Hokkaido). The Soviet census of 1926 counted 5 Ainu, while several of their multiracial children were recorded as ethnic Nivkh, Slav or Uilta.

- North Sakhalin: Only five pure-blooded individuals were recorded during the 1926 Soviet Census in Northern Sakhalin. Most of the Sakhalin Ainu (mainly from coastal areas) were relocated to Hokkaido in 1875 by Japan. The few that remained (mainly in the remote interior) were mostly married to Russians as can be seen from the works of Bronisław Piłsudski.[126]

- Southern Sakhalin (Karafuto): Japanese rule until 1945. Japan evacuated almost all the Ainu to Hokkaido after World War II. Isolated individuals might have remained on Sakhalin.[127] In 1949, there were about 100 Ainu living on Soviet Sakhalin.[128]

- Northern Kuril Ainu (no known living population in Japan, existence not recognized by Russian government in Kamchatka Krai): Also known as Kurile in Russian records. Were under Russian rule until 1875. First came under Japanese rule after the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1875). Major population was on the island of Shumshu, with a few others on islands like Paramushir. Altogether they numbered 221 in 1860. They had Russian names, spoke Russian fluently and were Russian Orthodox in religion. As the islands were given to the Japanese, more than a hundred Ainu fled to Kamchatka along with their Russian employers (where they were assimilated into the Kamchadal population).[128][129] Only about half remained under Japanese rule. In order to derussify the Kurile, the entire population of 97 individuals was relocated to Shikotan in 1884, given Japanese names, and the children were enrolled in Japanese schools. Unlike the other Ainu groups, the Kurile failed to adjust to their new surroundings and by 1933 only 10 individuals were alive (plus another 34 multiracial individuals). The last group of 20 individuals (including a few pure-bloods) were evacuated to Hokkaido in 1941, where they vanished as a separate ethnic group soon after.[126]

- Southern Kuril Ainu (no known living population): Numbered almost 2,000 people (mainly in Kunashir, Iturup and Urup) during the 18th century. In 1884, their population had decreased to 500. Around 50 individuals (mostly multiracial) who remained in 1941 were evacuated to Hokkaido by the Japanese soon after World War II.[128] The last full-blooded Southern Kuril Ainu was Suyama Nisaku, who died in 1956.[130] The last of the tribe (partial ancestry), Tanaka Kinu, died on Hokkaido in 1973.[130]

- Kamchatka Ainu (no known living population): Known as Kamchatka Kurile in Russian records. Ceased to exist as a separate ethnic group after their defeat in 1706 by the Russians. Individuals were assimilated into the Kurile and Kamchadal ethnic groups. Last recorded in the 18th century by Russian explorers.[65]

- Amur Valley Ainu (probably none remain): A few individuals married to ethnic Russians and ethnic Ulchi reported by Bronisław Piłsudski in the early 20th century.[131] Only 26 pure-blooded individuals were recorded during the 1926 Russian Census in Nikolaevski Okrug (present-day Николаевский район Nikolaevskij Region/District).[132] Probably assimilated into the Slavic rural population. Although no one identifies as Ainu nowadays in Khabarovsk Krai, there are a large number of ethnic Ulch with partial Ainu ancestry.[133][134]

See also

- Ainu-ken

- Akira Ifukube

- Bibliography of the Ainu

- Bronisław Piłsudski

- Constitution of Japan

- Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Emishi

- Ethnocide

- Hiram M. Hiller, Jr.

- Indigenous peoples

- Kankō Ainu

- Takashi Ukaji

- Shigeru Kayano

- Nibutani Dam

Ainu culture

Ethnic groups in Japan

References

- ↑ Poisson, Barbara Aoki (2002). The Ainu of Japan. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-82254-176-9.

- 1 2 "Results of the All-Russian Population Census of 2010 in relation to the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of individual nationalities". Federal State Statistics Service (in Russian).

"2010 Census: Population by ethnicity". Federal State Statistics (in Russian). Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. - ↑ Gordon, Raymond G. Jr., ed. (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (15th ed.). Dallas: SIL International. ISBN 1-55671-159-X. OCLC 224749653.

- ↑ Suzuki, Yuka (December 6, 2012). "Ryukyuan, Ainu People Genetically Similar". Asian Scientist.

- ↑ Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990). The Languages of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-521-36918-3.

- 1 2 3 Sato, Takehiro; et al. (2007). "Origins and genetic features of the Okhotsk people, revealed by ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis". Journal of Human Genetics. 52 (7): 618–627. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0164-z. PMID 17568987.

- ↑ 第59回 交易の民アイヌ Ⅶ 元との戦い (in Japanese). Asahikawa City. June 2, 2010. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ↑ Weiner, M., ed. (1997). Japan's Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41515-218-1.

- ↑ "Island of the Spirits – Origins of the Ainu". NOVA Online. PBS. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- 1 2 Walker, Brett (2001). The Conquest of Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590–1800. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 49–56, 61–71, 172–176. ISBN 978-0-52022-736-1.

- ↑ Shelton, Dinah (2005). Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. 2. Macmillan Reference.

- ↑ Howell, David (1997). "The Meiji State and the Logic of Ainu 'Protection'". In Hardacre, Helen. New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan. Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 614. ISBN 978-9-00410-735-9.

- 1 2 Sjöberg, Katarina (1993). The Return of the Ainu. Studies in Anthropology and History. 9. Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-3-71865-401-7.

- ↑ Loos, Noel; Osani, Takeshi, eds. (1993). Indigenous Minorities and Education: Australian and Japanese Perspectives on their Indigenous Peoples, the Ainu, Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Tokyo: Sanyusha Publishing Co., Ltd. ISBN 978-4-88322-597-2.

- 1 2 Fogarty, Philippa (June 6, 2008). "Recognition at last for Japan's Ainu". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ↑ Siddle, Richard (1996). Race, Resistance, and the Ainu of Japan. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-41513-228-2.

- ↑ Sjöberg, Katarina (1993). The Return of the Ainu. Studies in Anthropology and History. 9. Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers. p. 117. ISBN 978-3-71865-401-7.

- ↑ Levinson, David (2002). Encyclopedia of Modern Asia. 1. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-684-80617-4.

- ↑ Lewallen, Ann-Elise (October 2016). The Fabric of Indigeneity: Ainu Identity, Gender, and Settler Colonialism in Japan. University of New Mexico Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8263-5737-3.

- ↑ "アイヌ⇔ダブ越境!異彩を放つOKIの新作". HMV Japan (in Japanese). May 23, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ↑ Honna, Nobuyuki; Tajima, Hiroko Tina; Minamoto, Kunihiko (2000). "Japan". In Kam, Ho Wah; Wong, Ruth Y. L. Language Policies and Language Education: The Impact in East Asian Countries in the Next Decade. Singapore: Times Academic Press. ISBN 978-9-81210-149-5.

- ↑ Ito, M. (June 7, 2008). "Diet officially declares Ainu indigenous". The Japan Times. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ vostokmediaTV (March 21, 2011). Камчадальские айны добиваются признания [Kamchadal Ainu seek recognition]. YouTube (in Russian).

- 1 2 "Айны" [Ainu]. Kamchatka-Etno (in Russian). 2008. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012.

- ↑ "В России снова появились айны - самый загадочный народ Дальнего востока" [In Russia, the Ainu appear again - the most mysterious people of the Far East]. 5-tv.ru (in Russian). March 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Айны – древние и таинственные" [Ainu - ancient and mysterious]. russiaregionpress.ru (in Russian). March 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Айны просят включить их в Единый перечень коренных народов России" [Aina ask to be included in the Unified List of Indigenous Peoples of Russia]. severdv.ru (in Russian). July 5, 2011. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Алексей Накамура" [Alexey Nakamura]. nazaccent.ru (in Russian). January 17, 2012.

- ↑ Skvortsov, Ivan (January 29, 2012). "Айны – борцы с самураями" [Ainu - wrestlers with samurai]. Сегодня.ру (in Russian).

- ↑ Bogdanova, Svetlana (April 3, 2008). "Без национальности: Представители малочисленного народа хотят узаконить свой статус" [Without nationality: Representatives of a small number of people want to legitimize their status]. Rossiyskaya Gazeta (in Russian).

- ↑ McCarthy, Terry (September 22, 1992). "Ainu people lay ancient claim to Kurile Islands: The hunters and fishers who lost their land to the Russians and Japanese are gaining the confidence to demand their rights". The Independent.

- ↑ Yampolsky, Vladimir. "Трагедия Российского Дальнего Востока" [Tragedy of the Russian Far East]. Kamchatskoye Vremya (in Russian).

- ↑ "Представители малочисленного народа айну на Камчатке хотят узаконить свой статус" [Representatives of the Ainu people in Kamchatka want to legitimize their status]. indigenous.ru (in Russian).

- ↑ "The Ainu: one of Russia's indigenous peoples". Voice of Russia. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012.

- ↑ Howells, William W. (1997). Getting Here: The Story of Human Evolution (New ed.). Washington, D.C.: Compass Press. ISBN 978-0-92959-016-5.

- ↑ Denoon, Donald; McCormack, Gavan (2001). Multicultural Japan: Palaeolithic to Postmodern. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-521-00362-9.

- ↑ Sato, Takehiro; et al. (2007). "Origins and genetic features of the Okhotsk people, revealed by ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis". Journal of Human Genetics. 52 (7): 618–627. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0164-z. PMID 17568987.

- ↑ Lee, S.; Hasegawa, T. (2013). "Evolution of the Ainu Language in Space and Time". PLoS ONE. 8 (4): e62243. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062243. PMC 3637396. PMID 23638014.

- ↑ "NOVA Online – of the Spirits – Origins of the Ainu". Archived from the original on April 29, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ↑ Travis, John "Jomon Genes:Using DNA, researchers probe the genetic origins of modern Japanese", Science News February 15, 1997, Vol. 151, No. 7, p. 106 Travis, John (February 15, 1997). "Jomon genes: using DNA, researchers probe the genetic origins of modern Japanese". BNET. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ↑ Chisholm (1911).

- ↑ Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08750-4.

- ↑ Powell, Joseph F.; Rose, Jerome C. "Report on the Osteological Assessment of the Kennewick Man Skeleton (CENWW.97.Kennewick)". National Park Service. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ↑ https://www.nature.com/articles/jhg2016110

- ↑ Hudson, Mark J. (1999). Ruins of Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-82481-930-9.

- ↑ Landor, Arnold Henry Savage (1893). Alone with the Hairy Ainu: or, 3,800 Miles on a Pack Saddle in Yezo and a Cruise to the Kurile Islands. London: John Murray. pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-691-08750-4.

- ↑ Schurr, Theodore G. (2011). Mapping Mongolia: Situating Mongolia in the World from Geologic Time to the Present. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Pennsylvania. ISBN 1-934536-18-0

- ↑ Wu, Ju-kang (1959). "Human Fossils Found in Liukiang, Kwangsi, China" (PDF). Paleovertebrata et Paleoanthropologia. 1 (3): 97–104.

- ↑ Lahr M. M. (1995). "Patterns of modern human diversification: Implications for Amerindian origins". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 38: 163–198. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330380609.

- ↑ Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko (1981). Illness and healing among the Sakhalin Ainu: a symbolic interpretation. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-23636-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Tajima, Atsushi; et al. (2004). "Genetic origins of the Ainu inferred from combined DNA analyses of maternal and paternal lineages". Journal of Human Genetics. 49 (4): 187–193. doi:10.1007/s10038-004-0131-x. PMID 14997363.

- ↑ McDonald, J. D. (2005). "Y Haplogroups of the World Map" (PDF). University of Illinois. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ↑ Hammer, Michael F.; et al. (2006). "Dual origins of the Japanese: Common ground for hunter-gatherer and farmer Y chromosomes". Journal of Human Genetics. 51 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0322-0. PMID 16328082.

- 1 2 Tanaka, Masashi; et al. (2004). "Mitochondrial Genome Variation in Eastern Asia and the Peopling of Japan". Genome Research. 14 (10A): 1832–1850. doi:10.1101/gr.2286304. PMC 524407. PMID 15466285.

- ↑ Adachi, Noboru; Ken-ichi, Shinoda; Umetsu, Kazuo; Matsumura, Hirofumi (2009). "Mitochondrial DNA Analysis of Jomon Skeletons From the Funadomari Site, Hokkaido, and Its Implication for the Origins of Native American". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 138: 255–265. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20923. PMID 18951391.

- ↑ Takehiro SATO, Tetsuya AMANO, Hiroko ONO et al., "Mitochondrial DNA haplogrouping of the Okhotsk people based on analysis of ancient DNA: an intermediate of gene flow from the continental Sakhalin people to the Ainu," Anthropological Science Vol. 117(3), 171–180, 2009.

- ↑ M. Tanaka, V. M. Cabrera, A. M. González et al. (2004), "Mitochondrial Genome Variation in Eastern Asia and the Peopling of Japan"

- ↑ Uchiyama, Taketo; Hisazumi, Rinnosuke; Shimizu, Kenshi; et al. (2007). "Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation and Phylogenetic Analysis in Japanese Individuals from Miyazaki Prefecture". Japanese Journal of Forensic Science and Technology. 12 (1): 83–96. doi:10.3408/jafst.12.83.

- ↑ Shigematsu, Masahito; et al. (2004). "Morphological affinities between Jomon and Ainu: Reassessment based on nonmetric cranial traits". Anthropological Science. 112 (2): 161–172. doi:10.1537/ase.00092.

- ↑ Suzuki, Yuka (December 6, 2012). "Ryukyuan, Ainu People Genetically Similar". Asian Scientist.

- ↑ Jeong, Choongwon; Nakagome, Shigeki; Rienzo, Anna Di (2016-01-01). "Deep History of East Asian Populations Revealed Through Genetic Analysis of the Ainu". Genetics. 202 (1): 261–272. doi:10.1534/genetics.115.178673. ISSN 0016-6731. PMID 26500257.

- ↑ Hohmann, S. (2008). "The Ainu's modern struggle". World Watch. 21 (6): 20–24.

- ↑ Vovin, A. (1993). A Reconstruction of Proto-Ainu. Leiden: Brill. p. 3.

- 1 2 Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990). The Languages of Japan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-521-36918-3.

- ↑ "Ainu". omniglot.com. 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

- Rev. John Batchelor, The Ainu and their Folk-lore (London, 1901)

- Isabella Bird (Mrs Bishop), Korea and her Neighbours (1898)

- Basil Hall Chamberlain, Language, Mythology and Geographical Nomenclature of Japan viewed in the Light of Aino Studies and Aino Fairy-tales (1895)

- Romyn Hitchcock, The Ainos of Japan (Washington, 1892)

- H. von Siebold, Über die Aino (Berlin, 1881)

- ↑ "Columbia River Basin". Bureau of Land Management. February 25, 2009. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009.

- ↑ Katarina Sjoberg (31 October 2013). The Return of Ainu: Cultural mobilization and the practice of ethnicity in Japan. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-35198-5.

- ↑ Nuttall, Mark (2012). Encyclopedia of the Arctic. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-136-78680-8.

- ↑ Phillipi, Donald L. (2015). Songs of Gods, Songs of Humans: The Epic Tradition of the Ainu. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-40087-069-1.

- ↑ Ishikida, Miki Y. (2005). Living Together: Minority People and Disadvantaged Groups in Japan. iUniverse. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-59535-032-2.

- ↑ West, Barbara A. (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-43811-913-7.

- ↑ Pollard, Nick; Sakellariou, Dikaios (2012). Politics of Occupation-Centred Practice: Reflections on Occupational Engagement Across Cultures. John Wiley & Sons. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-11829-098-9.

- ↑ Sjöberg, Katarina (2013). The Return of the Ainu. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-13435-198-5.

- ↑ Landor, Arnold Henry Savage (2012). Alone with the Hairy Ainu: or, 3,800 Miles on a Pack Saddle in Yezo and a Cruise to the Kurile Islands. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-10804-941-2.

- ↑ Barceloux, Donald G. (2012). Medical Toxicology of Natural Substances: Foods, Fungi, Medicinal Herbs, Plants, and Venomous Animals. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1785. ISBN 978-1-11838-276-9.

- ↑ Advances in Marine Biology. Academic Press. 1984. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-08057-944-3.

- ↑ Poisson, Barbara Aoki (2002). The Ainu of Japan. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-82254-176-9.

- ↑ Batchelor, John (1901). The Ainu and their folk-lore. London: The Religious Tract Society. p. 116.

- 1 2 Walker, Brett (2006). The Conquest of Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590–1800. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-52024-834-2.

- ↑ Siddle, Richard (2012). Race, Resistance, and the Ainu of Japan. Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-13482-680-3.

- ↑ Reilly, Kevin; Kaufman, Stephen; Bodino, Angela (2003). Racism: A Global Reader. M.E. Sharpe. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-76561-060-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ancient Japan. Social Studies School Service. 2006. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-56004-256-3.

- ↑ Fitzhugh, William W.; Dubreuil, Chisato O. (1999). Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People. Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution in association with University of Washington Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-96734-290-0.

- ↑ Tribal: The Magazine of Tribal Art. Primedia Inc. 2003. pp. 76 & 78.

- ↑ "Ainu History and Culture". Ainu Museum. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ↑ Fitzhugh, William W.; Dubreuil, Chisato O. (1999). Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People. Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution in association with University of Washington Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-96734-290-0.

Some glass beads were brought to the Ainu through trade with the Asian continent, but others were secretly made by the Matsumae clan at their headquarters in Hakodate.

- ↑ Batchelor, John (1901). The Ainu and their folk-lore. London: The Religious Tract Society. p. 223.

- ↑ Goodrich, J. K. (April 1889). "Ainu Family Life and Religion". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. XXXVI: 85.

- 1 2 Poisson, Barbara Aoki (2002). The Ainu of Japan. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-82254-176-9.

- ↑ Batchelor, John (1901). The Ainu and their folk-lore. London: The Religious Tract Society. p. 226.

- ↑ Abbotts, The (2015-08-15). Native Wisdom - Unusual Customs and Rites from Native Cultures. Lulu.com. p. 98. ISBN 9781326391812.

- ↑ Refsing, Kirsten (2002). Early European Writings on Ainu Culture: Religion and Folklore. Psychology Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-70071-486-5.

- 1 2 Poisson, Barbara Aoki (2002). The Ainu of Japan. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-82254-176-9.

- ↑ Landor, Arnold Henry Savage (2012). Alone with the Hairy Ainu: or, 3,800 Miles on a Pack Saddle in Yezo and a Cruise to the Kurile Islands. Cambridge University Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-10804-941-2.

- ↑ Fitzhugh, William W.; Dubreuil, Chisato O. (1999). Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People. Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution in association with University of Washington Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-96734-290-0.

Ainu women's underclothes were called mour, literally "deer," a sort of one-piece dress with an open front, ...

- ↑ Kindaichi, Kyōsuke (1941). Ainu Life and Legends. Board of Tourist Industry, Japanese Government Railways. p. 30.

One is a nettle-hemp braid named pon kut (small sash) or ra-nn kut (under sash).

- ↑ Batchelor, John (1901). The Ainu and their folk-lore. London: The Religious Tract Society. pp. 51–52. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ↑ "Center for Ainu & Indigenous Studies". Hokkaido University. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- 1 2 "Documentary Film "TOKYO Ainu"". www.2kamuymintara.com. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ↑ "ドキュメンタリー映画 TOKYO アイヌ 首都圏アイヌ団体紹介". www.2kamuymintara.com (in Japanese). Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ↑ Levin, Mark A. (2001). "Essential Commodities and Racial Justice: Using Constitutional Protection of Japan's Indigenous Ainu People to Inform Understandings of the United States and Japan". New York University Journal of International Law and Politics. 33: 445–446.

- 1 2 3 Levin, Mark (1999). "Kayano et al. v. Hokkaido Expropriation Committee: 'The Nibutani Dam Decision'". International Legal Materials. 38: 394. SSRN 1635447.

- ↑ Levin (2001), pp. 419, 447.

- ↑ Levin (2001), p. 443.

- ↑ Levin, Mark (2008). "The Wajin's Whiteness: Law and Race Privilege in Japan". Hōritsu Jihō. 80 (2).

- ↑ "Constitution of Japan (November 3, 1946)". Solon.org.

- ↑ "International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008.

- 1 2 Yoshida Hitchingham, Masako (2000). "Act for the Promotion of Ainu Culture and Dissemination of Knowledge Regarding Ainu Traditions – A Translation of the Ainu Shinpou" (PDF). Asian–Pacific Law & Policy Journal. 1 (1). Retrieved June 20, 2012.

The law's original Japanese text is available at Wikisource. - ↑ Levin (2001), p. 467.

- ↑ "Database of Registered National Cultural Properties". Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ↑ Levin & Tsunemoto, Oklahoma Law Review.

- 1 2 Siddle, Richard (1996). Race, Resistance, and the Ainu of Japan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41513-228-2.

- ↑ "Ainu Party". ainu-org.jp. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Ainu plan group for Upper House run". The Japan Times. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012.

- ↑ "参議院選挙" [House of Councillors election]. Asahi Shimbun (in Japanese). Archived from the original on July 9, 2012.

- ↑ Walker, Brett (2001). The Conquest of Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590–1800. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-52022-736-1.

- 1 2 Siddle, Richard (1997). Japan's Minorities. London: Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 0-415-13008-5.

- ↑ Shim, Karen (May 31, 2004). "Will the Ainu language die?". TalkingITGlobal. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ↑ Yokoyama, Yuzuru. "Human Right Issues on the Ainu People in Japan". China.org. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ↑ "First nationwide survey on Ainu discrimination to be carried out". The Japan Times. August 29, 2014. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ↑ Siddle, Richard (1996). Race, Resistance, and the Ainu of Japan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41513-228-2.

- ↑ 本多勝一 (2000). Harukor: An Ainu Woman's Tale. University of California Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-520-21020-2.

- ↑ "Ⅵ 〈東北〉史の意味と射程". Joetsu University of Education (in Japanese). Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- 1 2 Howell, David L. (2005). Geographies of Identity in 19th Century Japan. University of California Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-520-24085-8.

- ↑ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1926 года. Национальный состав населения по регионам РСФСР. дальне-Восточныи: Саxалинскии округ" [All-Union Population Census of 1926. National composition of the population by regions of the RSFSR. Far East: Sakhalin District]. Central Statistical Office of the USSR. 1929 – via Демоскоп Weekly.

- 1 2 3 Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tyron, Darrell T. (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Maps. Walter de Gruyter. p. 1010. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- ↑ Minichiello, Sharon (1998). Japan's Competing Modernities: Issues in Culture and Democracy, 1900-1930. University of Hawaii Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-8248-2080-0.

- 1 2 Harrison, Scott (2007). The Indigenous Ainu of Japan and the "Northern Territories" Dispute (PDF) (Thesis). University of Waterloo.

- ↑ Piłsudski, Bronisław; Majewicz, Alfred F. (December 30, 2004). Materials for the Study of the Ainu Language and Folklore 2: Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter. p. 816. ISBN 978-3-11-017614-8.

- ↑ Всесоюзная перепись населения 1926 года. Национальный состав населения по регионам РСФСР. дальне-Восточныи: Николаевскии округ [All-Union Population Census of 1926. National composition of the population by regions of the RSFSR. Far East: Nikolaevsky District]. Central Statistical Office of the USSR. 1929 – via Демоскоп Weekly.

- ↑ Shaman: an international journal for Shamanistic research, Volumes 4–5, p.155.

- ↑ Piłsudski, Bronisław; Majewicz, Alfred F. (December 30, 2004). Materials for the Study of the Ainu Language and Folklore 2: Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter. p. 37. ISBN 978-3-11-017614-8.

Sources

- Japan Times. Ainu Plan Group for Upper House Run, October 31, 2011

- Hudson, Mark J (1999). "Ainu Ethnogenesis and the Northern Fujiwara". Arctic Anthropology. 36 (1/2): 73–83. JSTOR 40316506.

- Levin, Mark A. (2001). "Essential Commodities and Racial Justice: Using Constitutional Protection of Japan's Indigenous Ainu People to Inform Understandings of the United States and Japan". New York University Journal of International Law and Politics. 33: 419, 447. SSRN 1635451.

Further reading

- Batchelor, John (1901). "On the Ainu Term `Kamui". The Ainu and Their Folklore. London: Religious Tract Society.

- Etter, Carl (2004) [1949]. Ainu Folklore: Traditions and Culture of the Vanishing Aborigines of Japan. Whitfish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4179-7697-7.

- Fitzhugh, William W.; Dubreuil, Chisato O. (1999). Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97912-7. OCLC 42801973.

- Honda Katsuichi (1993). Ainu Minzoku (in Japanese). Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun Publishing. ISBN 4-02-256577-2. OCLC 29601145.

- Ichiro Hori (1968). Folk Religion in Japan: Continuity and Change. Haskell lectures on History of religions. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Junko Habu (2004). Ancient Jomon of Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77670-8. OCLC 53131386.

- Hitchingham, Masako Yoshida (trans.), Act for the Promotion of Ainu Culture & Dissemination of Knowledge Regarding Ainu Traditions, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal, vol. 1, no. 1 (2000).

- Kayano, Shigeru (1994). Our Land Was A Forest: An Ainu Memoir. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-1880-7. ISBN 978-0-8133-1880-6.

- Landor, A. Henry Savage (1893). Alone with the Hairy Ainu. Or, 3,800 miles on a Pack Saddle in Yezo and a Cruise to the Kurile Islands. London: John Murray.

- Levin, Mark (2001). Essential Commodities and Racial Justice: Using Constitutional Protection of Japan's Indigenous Ainu People to Inform Understandings of the United States and Japan (2001). 33. New York University of International Law and Politics. p. 419. SSRN 1635451.

- Levin, Mark (1999). Kayano et al. v. Hokkaido Expropriation Committee: 'The Nibutani Dam Decision'. International Legal Materials. 38. p. 394. SSRN 1635447.

- Siddle, Richard (1996). Race, Resistance and the Ainu of Japan. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13228-2. OCLC 243850790.

- Starr, Frederick (1905). "The Hairy Ainu of Japan". Proceedings of the Second Yearly Meeting of the Iowa Anthropological Association. Iowa City: State Historical Society of Iowa.

- Walker, Brett (2001). The Conquest of Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590–1800. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22736-0. OCLC 45958211.

- Article on the Ainu in Japan's Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity.

- John Batchelor (1901). The Ainu and their folk-lore. London: Religious Tract Society. p. 603. Retrieved March 1, 2012. (Harvard University)(Digitized Jan 24, 2006)

- John Batchelor (1892). The Ainu of Japan: the religion, superstitions, and general history of the hairy aborigines of Japan. London: Religious Tract Society. p. 336. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- Basil Hall Chamberlain (ed.). Aino Folk-Tales. Forgotten Books. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

1606200879

- Basil Hall Chamberlain (1888). Aino folk-tales: By Basil Hall Chamberlain. With introduction by Edward B. Taylor. Publications of the Folklore Society. 22. Saxony: Privately printed for the Folk-lore Society. p. 57. Retrieved March 1, 2012 – via C.G. Röder, Ltd., Leipsic. (Indiana University) (digitized Sep 3, 2009)

- Batchelor, John; Miyabe, Kingo (1898). Ainu economic plants. Volume 21. p. 43. Retrieved 23 April 2012. [Original from Harvard University Digitized Jan 30, 2008] [YOKOHAMA : R. MEIKLEJOHN & CO., NO 49.]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ainu. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Aino Folk-Tales, Chamberlain, B. H. Folk-Lore Society, 1888. (Members edition, without expurgation) |

- Organizations

- Hokkaido Utari Kyokai/Ainu Association of Hokkaido (in Japanese)/(in English)

- Sapporo Pirka Kotan Ainu Cultural Center

- Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture (centers located in Sapporo and Tokyo) (in Japanese)/(in English)

- Hokkaido University Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies

- Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Ainu in Samani, Hokkaido

- Museums and exhibits

- Smithsonian Institution

- The Boone Collection

- Nibutani Ainu Cultural Museum (in Japanese)

- The Ainu Museum at Shiraoi

- Ainu Komonjo (18th & 19th century records) – Ohnuki Collection

- The Regions: North America—Ainu–North American cultural similarities

- Articles

- "Black Shogun: An Assessment of the African Presence in Early Japan" by Runoko Rashidi—Ainu lineage

- "Japan's Ainu hope new identity leads to more rights" in The Christian Science Monitor, June 9, 2008

- A Salmon's Life: An Incredible Journey (Columbia River basin, June 8, 2016)—Posterback Activities

- Video