Aconitum

| Aconitum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Aconitum variegatum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Ranunculales |

| Family: | Ranunculaceae |

| Subfamily: | Ranunculoideae |

| Tribe: | Delphinieae |

| Genus: | Aconitum L. |

| Subgenera[1] | |

| |

Aconitum (/ˌækəˈnaɪtəm/),[2] commonly known as aconite, monkshood, wolf's bane, leopard's bane, mousebane, women's bane, devil's helmet, queen of poisons, or blue rocket, is a genus of over 250 species of flowering plants belonging to the family Ranunculaceae. These herbaceous perennial plants are chiefly native to the mountainous parts of the Northern Hemisphere,[3] growing in the moisture-retentive but well-draining soils of mountain meadows. Most species are extremely poisonous[4] and must be dealt with very carefully.

Etymology

The name aconitum comes from the Greek ἀκόνιτον, which may derive from the Greek akon for dart or javelin, the tips of which were poisoned with the substance, or from akonae, because of the rocky ground on which the plant was thought to grow.[5] The Greek name lycotonum, which translates literally to "wolf's bane", is thought to indicate the use of its juice to poison arrows or baits used to kill wolves.[6]

Description

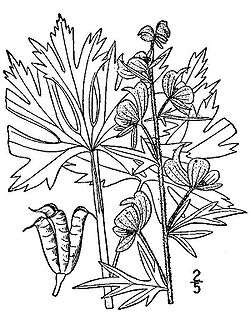

The dark green leaves of Aconitum species lack stipules. They are palmate or deeply palmately lobed with five to seven segments. Each segment again is trilobed with coarse sharp teeth. The leaves have a spiral (alternate) arrangement. The lower leaves have long petioles.

The tall, erect stem is crowned by racemes of large blue, purple, white, yellow, or pink zygomorphic flowers with numerous stamens. They are distinguishable by having one of the five petaloid sepals (the posterior one), called the galea, in the form of a cylindrical helmet, hence the English name monkshood.[3] Two to 10 petals are present. The two upper petals are large and are placed under the hood of the calyx and are supported on long stalks. They have a hollow spur at their apex, containing the nectar. The other petals are small and scale-like or nonforming. The three to five carpels are partially fused at the base.

The fruit is an aggregate of follicles, a follicle being a dry, many-seeded structure.

Ecology

Aconitum species have been recorded as food plant of the caterpillars of several moths. The yellow tiger moth Arctia flavia, and the purple-shaded gem Euchalcia variabilis are at home on A. vulparia.[7] The engrailed Ectropis crepuscularia, yellow-tail Euproctis similis, mouse moth Amphipyra tragopoginis, pease blossom Periphanes delphinii, and Mniotype bathensis, have been observed feeding on A. napellus. The purple-lined sallow Pyrrhia exprimens, and Blepharita amica were found eating from A. septentrionale. The dot moth Melanchra persicariae occurs both on A. septentrionale and A. intermedium. The golden plusia Polychrysia moneta is hosted by A. vulparia, A. napellus, A. septentrionale, and A. intermedium. Other moths associated with Aconitum species include the wormwood pug Eupithecia absinthiata, satyr pug E. satyrata, Aterpia charpentierana, and A. corticana.[8] It is also the primary food source for the Old World bumblebee Bombus consobrinus.[9][10]

Uses

The roots of A. ferox supply the Nepalese poison called bikh, bish, or nabee. It contains large quantities of the alkaloid pseudaconitine, which is a deadly poison. The root of A. luridum, of the Himalaya, is said to be as poisonous as that of A. ferox or A. napellus.[3]

Several species of Aconitum have been used as arrow poisons. The Minaro in Ladakh use A. napellus on their arrows to hunt ibex, while the Ainu in Japan used a species of Aconitum to hunt bear.[11] The Chinese also used Aconitum poisons both for hunting[12] and for warfare.[13] Aconitum poisons were used by the Aleuts of Alaska's Aleutian Islands for hunting whales. Usually, one man in a kayak armed with a poison-tipped lance would hunt the whale, paralyzing it with the poison and causing it to drown.[14]

Cultivation

The more common species of Aconitum are generally those cultivated in gardens, especially hybrids. They typically thrive in well-drained evenly moist garden soils like the related hellebores and delphiniums, and can grow in the shade of trees. They can be propagated by divisions of the root or by seeds; care should be taken not to leave pieces of the root where livestock might be poisoned. All parts of the plant should be handled while wearing protective disposable gloves.[3] Unlike Helleborus and Delphinium, there are no double-flowered hybrid forms. Aconitum plants are typically much longer-lived than the closely related delphinium plants, putting less energy into floral reproduction. As with hellebores and some others in the family, they do not like to be moved once established and seeds that are not planted soon after harvesting should be stored moist-packed in vermiculite to avoid dormancy and viability issues.

Cultivars

In the UK, the following have gained the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit:-

Color range

A medium to dark semi-saturated blue-purple is the typical flower color for Aconitum species. Aconitum species tend to be variable enough in form and color in the wild to cause debate and confusion among experts when it comes to species classification boundaries. The overall color range of the genus is rather limited, although the palette has been extended a small amount with hybridization. In the wild, some Aconitum blue-purple shades can be very dark. In cultivation the shades do not reach this level of depth.

Aside from blue-purple — white, very pale greenish white, creamy white, and pale greenish yellow are also somewhat common in nature. Wine red (or red-purple) occurs in several uncommon or rare Asian species, including a climbing variety. There is a pale semi-saturated pink produced by cultivation as well as bicolor hybrids (e.g. white centers with blue-purple edges). Purplish shades range from very dark blue-purple to a very pale lavender that is quite greyish. The latter occurs in the "Stainless Steel" hybrid.

Neutral blue (rather than purplish or greenish), greenish blue, and intense blues, available in some related Delphinium plants — particularly Delphinium grandiflorum — do not occur in this genus. Aconitum plants that have purplish blue flowers are often inaccurately referred to as having blue flowers, even though the purple tone dominates. If there are species with true (neutral) blue or greenish blue flowers they are rare and do not occur in cultivation. Also unlike the genus Delphinium, there are no true or bright red or intense pink Aconitum plants, as none known evolved to be pollinated by hummingbirds. There are no orange-flowered varieties nor are any green-flowered. Aconitum is typically more intense in color than Helleborus but less intense than Delphinium. There are no black-like flowers in Aconitum, unlike Helleborus.

Toxicology

Marked symptoms may appear almost immediately, usually not later than one hour, and "with large doses death is almost instantaneous". Death usually occurs within two to six hours in fatal poisoning (20 to 40 ml of tincture may prove fatal).[19] The initial signs are gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. This is followed by a sensation of burning, tingling, and numbness in the mouth and face, and of burning in the abdomen.[3] In severe poisonings, pronounced motor weakness occurs and cutaneous sensations of tingling and numbness spread to the limbs. Cardiovascular features include hypotension, sinus bradycardia, and ventricular arrhythmias. Other features may include sweating, dizziness, difficulty in breathing, headache, and confusion. The main causes of death are ventricular arrhythmias and asystole, or paralysis of the heart or respiratory center.[19][20] The only post mortem signs are those of asphyxia.[3]

Treatment of poisoning is mainly supportive. All patients require close monitoring of blood pressure and cardiac rhythm. Gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal can be used if given within one hour of ingestion.[21] The major physiological antidote is atropine, which is used to treat bradycardia. Other drugs used for ventricular arrhythmia include lidocaine, amiodarone, bretylium, flecainide, procainamide, and mexiletine. Cardiopulmonary bypass is used if symptoms are refractory to treatment with these drugs.[20] Successful use of charcoal hemoperfusion has been claimed in patients with severe aconitine poisoning.[22]

Severe toxicity is not expected from skin contact; however paraesthesia has been reported, as has mild toxicity (headache, nausea and palpitations).

Aconitine is a potent neurotoxin that opens tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels. It increases influx of sodium through these channels and delays repolarization, thus increasing excitability and promoting ventricular dysrhythmias.

Medicinal use

Aconite has long been used in traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda. Aconite was also described in Greek and Roman medicine by Theophrastus, Dioscorides, and Pliny the Elder, who most likely prescribed the Alpine species Aconitum lycoctonum.. Folk medicinal use of Aconitum species is still practiced in some parts of Slovenia.[23]

Aconitum chasmanthum is listed as critically endangered,[24] Aconitum heterophyllum as endangered,[25] and Aconitum violaceum as vulnerable due to overcollection for Ayurvedic use.[26]

Taxonomy

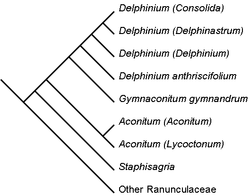

Genetic analysis suggests that Aconitum as it was delineated before the 21st century is nested within Delphinium sensu lato, that also includes Aconitella, Consolida, Delphinium staphisagria, D. requini, and D. pictum.[1] Further genetic analysis has shown that the only species of the subgenus "Aconitum (Gymnaconitum)", "A. gymnandrum", is sister to the group that consists of Delphinium (Delphinium), Delphinium (Delphinastrum), and "Consolida" plus "Aconitella". To make Aconitum monophyletic, "A. gymnandrum" has now been reassigned to a new genus, Gymnaconitum. To make Delphinium monophyletic, the new genus Staphisagria was erected containing S. staphisagria, S. requini, and S. pictum.[27]

Species

- Aconitum ajanense

- Aconitum albo-violaceum

- Aconitum altaicum

- Aconitum ambiguum

- Aconitum angusticassidatum

- Aconitum anthora (yellow monkshood)

- Aconitum anthoroideum

- Aconitum album

- Aconitum axilliflorum

- Aconitum baburinii

- Aconitum baicalense

- Aconitum barbatum

- Aconitum besserianum

- Aconitum biflorum

- Aconitum bucovinense

- Aconitum burnatii

- Aconitum carmichaelii (Carmichael's monkshood)

- Aconitum charkeviczii

- Aconitum chasmanthum

- Aconitum chinense Siebold.&Zucc.[28] aka Aconitum carmichaelii var. truppelianum

- Aconitum cochleare

- Aconitum columbianum (western monkshood)

- Aconitum confertiflorum

- Aconitum consanguineum

- Aconitum coreanum

- Aconitum crassifolium

- Aconitum cymbulatum

- Aconitum czekanovskyi

- Aconitum decipiens

- Aconitum degenii (syn. A. variegatum ssp. paniculatum)

- Aconitum delphinifolium (larkspurleaf monkshood)

- Aconitum desoulavyi

- Aconitum ferox (Indian aconite)

- Aconitum firmum

- Aconitum fischeri (Fischer monkshood)

- Aconitum flerovii

- Aconitum gigas

- Aconitum gracile (synonym of A. variegatum ssp. variegatum)

- Aconitum helenae

- Aconitum hemsleyanum (climbing monkshood)

- Aconitum henryi (Sparks variety monkshood)

- Aconitum hosteanum

- Aconitum infectum (Arizona monkshood)

- Aconitum jacquinii (synonym of A. anthora)

- Aconitum jaluense

- Aconitum jenisseense

- Aconitum karafutense

- Aconitum karakolicum

- Aconitum kirinense

- Aconitum koreanum

- Aconitum krylovii

- Aconitum kunasilense

- Aconitum kurilense

- Aconitum kusnezoffii (Kusnezoff monkshood)

- Aconitum kuzenevae

- Aconitum lamarckii

- Aconitum lasiostomum

- Aconitum leucostomum

- Aconitum longiracemosum

- Aconitum lycoctonum (northern wolfsbane)

- Aconitum macrorhynchum

- Aconitum maximum (Kamchatka aconite)

- Aconitum miyabei

- Aconitum moldavicum

- Aconitum montibaicalense

- Aconitum nanum

- Aconitum napellus (monkshood; type species)

- Aconitum nasutum

- Aconitum nemorum

- Aconitum neosachalinense

- Aconitum noveboracense (northern blue monkshood)

- Aconitum ochotense

- Aconitum orientale

- Aconitum paniculatum

- Aconitum paradoxum

- Aconitum pascoi

- Aconitum pavlovae

- Aconitum pilipes

- Aconitum plicatum

- Aconitum podolicum

- Aconitum productum

- Aconitum pseudokusnezowii

- Aconitum puchonroenicum

- Aconitum raddeanum

- Aconitum ranunculoides

- Aconitum reclinatum (trailing white monkshood)

- Aconitum rogoviczii

- Aconitum romanicum

- Aconitum rotundifolium

- Aconitum rubicundum

- Aconitum sachalinense

- Aconitum sajanense

- Aconitum saxatile

- Aconitum sczukinii

- Aconitum septentrionale

- Aconitum seravschanicum

- Aconitum sichotense

- Aconitum smirnovii

- Aconitum soongaricum

- Aconitum stoloniferum

- Aconitum stubendorffii

- Aconitum subalpinum

- Aconitum subglandulosum

- Aconitum subvillosum

- Aconitum sukaczevii

- Aconitum taigicola

- Aconitum talassicum

- Aconitum tanguticum

- Aconitum tauricum

- Aconitum turczaninowii

- Aconitum umbrosum

- Aconitum uncinatum (southern blue monkshood)

- Aconitum variegatum

- Aconitum violaceum

- Aconitum volubile

- Aconitum vulparia (wolf's bane)

- Aconitum woroschilovii

Natural hybrids

- Aconitum × austriacum

- Aconitum × cammarum

- Aconitum × hebegynum

- Aconitum × oenipontanum (A. variegatum ssp. variegatum × ssp. paniculatum)

- Aconitum × pilosiusculum

- Aconitum × platanifolium (A. lycoctonum ssp. neapolitanum × ssp. vulparia)

- Aconitum × zahlbruckneri (A. napellus ssp. vulgare × A. variegatum ssp. variegatum)

In media

As a poison

Aconite has been understood as a poison from ancient times, and is frequently represented as such in fiction. In Greek mythology, the goddess Hecate is said to have invented aconite,[29] which Athena used to transform Arachne into a spider.[30] Also, Medea attempted to poison Theseus with a cup of wine poisoned with wolf's bane.[31] The kyōgen (traditional Japanese comedy) play Busu (附子, "Dried aconite root"),[32] which is well-known and frequently taught in Japan, is centered on dried aconite root used for traditional Chinese medicine. Taken from Shasekishu, a 13th-century anthology collected by Mujū, the story describes servants who decide that the dried aconite root is really sugar, and suffer unpleasant though nonlethal symptoms after eating it.[33] Shakespeare, in Henry IV Part II Act 4 Scene 4 refers to aconite, alongside rash gunpowder, working as strongly as the "venom of suggestion" to break up close relationships.

As a well-known poison from ancient times, aconite is well-suited for historical fiction. It is the poison used by a murderer in the third of the Cadfael Chronicles, Monk's Hood by Ellis Peters, published in 1980 and set in 1138 in Shrewsbury. In I, Claudius, Livia, wife of Augustus, was portrayed discussing the merits, antidotes, and use of aconite with a poisoner. It also makes a showing in alternate history novels and historical fantasy, such as S. M. Stirling's, On the Oceans of Eternity, where a renegade warlord is poisoned with aconite-laced food by his own chief of internal security, and in the television show Merlin, the lead character, Merlin, attempts to poison Arthur with aconite while under a spell. In the 2003 Korean television series Dae Jang Geum, set in the 15th and 16th centuries, Choi put wolf's bane in the previous queen's food.

Aconite also lends itself to use as a fictional poison in modern settings. An overdose of aconite was the method by which Rudolph Bloom, father of Leopold Bloom in James Joyce's Ulysses, committed suicide. In the television series Midsomer Murders, season four, episode one ("Garden of Death"), aconite is used as a murder weapon, mixed into fettuccine with pesto to mask the taste.[34] In the Australian detective series Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries, series one, episode five ("Raisins and Almonds"), the ground root of wolf's bane is used as a murder weapon. In Rizzoli and Isles season one, episode three "Sympathy For The Devil", Maura Isles discovered a teenaged boy named Matisse killed by monkshood mixed into a water bottle. In the 2014 season of NCIS:LA, assistant director, Owen Granger, and members of his staff are poisoned with "monkshood" by a mole within the agency. In the TV series Dexter (season seven), the character Hannah McKay uses aconite to poison some of her victims. In the 2014 pilot episode of Forever, monkshood is used to murder a train conductor leading to a subway train collision.

Wolf's bane

In his mythological poem Metamorphoses, Ovid tells how the herb comes from the slavering mouth of Cerberus, the three-headed dog that guarded the gates of Hades.[35] As the veterinary historian John Blaisdell has noted, symptoms of aconite poisoning in humans bear some passing similarity to those of rabies: frothy saliva, impaired vision, vertigo, and finally a coma. Thus, some ancient Greeks possibly would have believed that this poison, mythically born of Cerberus's lips, was literally the same as that to be found inside the mouth of a rabid dog.[36]

In John Keats' poem Ode to Melancholy wolf's bane is mentioned in the first verse as the source of "poisonous wine" possibly referring to Medea.

In the 1931 classic horror film Dracula starring Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula and Helen Chandler as Mina Seward, reference is made to wolf's bane (aconitum). Towards the end of the film, "Van Helsing holds up a sprig of wolf's bane". Van Helsing educates the nurse protecting Mina from Count Dracula to place sprigs of wolf's bane around Mina's neck for protection. Furthermore, he instructs that wolf's bane is a plant that grows in central Europe. There, the natives use it to protect themselves against vampires. As long as the wolf's bane is present in Mina's bedroom, she will be safe from Count Dracula. During the night, Count Dracula desires to visit Mina. He appears outside her window in the form of a flying bat. He causes the nurse to become drowsy, and when she awakes from his spell, she removes the sprigs of wolf's bane, placing it in a hallway chest of drawers. With the removal of the wolf's bane from Mina's room, Count Dracula mysteriously appears and transports Mina to the dungeon of the castle.[37]

In the 1941 film The Wolf Man starring Lon Chaney Jr. and Claude Rains, the following poem is recited several times Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolf-bane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.[38]

In the 1943 French novel Our Lady of the Flowers, the boy Culafroy eats "Napel aconite", so that the "Renaissance would take possession of the child through the mouth."[39]

In mysticism

Wolf's bane is used as an analogy for the power of divine communion in Liber 65 1:13–16, one of Aleister Crowley's Holy Books of Thelema. Wolf's bane is mentioned in one verse of Lady Gwen Thompson's 1974 poem "Rede of the Wiccae", a long version of the Wiccan Rede: "Widdershins go when Moon doth wane, An the werewolves howl by the dread wolfsbane."

Gallery

Trailing white monkshood (A. reclinatum)

Trailing white monkshood (A. reclinatum) Southern blue monkshood (A. uncinatum)

Southern blue monkshood (A. uncinatum) Wild Alaskan monkshood (A. delphinifolium) is a flowering species that belongs to the family Ranunculaceae. The picture was taken in Kenai National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska.

Wild Alaskan monkshood (A. delphinifolium) is a flowering species that belongs to the family Ranunculaceae. The picture was taken in Kenai National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska.

References

- 1 2 Jabbour, Florian; Renner, Susanne S. (2012). "A phylogeny of Delphinieae (Ranunculaceae) shows that Aconitum is nested within Delphinium and that Late Miocene transition to long lifecycles in the Himalayas and Southwest China coincide with bursts in diversification". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 62: 928–942. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.12.005.

- ↑ Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

- 1 2 3 4 5 6

- ↑ Hay, R. (Consultant Editor) second edition 1978. Reader's Digest Encyclopedia of Garden Plants and Flowers. The Reader's Digest Association Limited.

- ↑ "Aconite Poisoning". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ "A Modern Herbal | Aconite Herb". botanical.com. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Bellmann, Heiko (2003). Der neue Kosmos Schmetterlingsführer. Stuttgard: Franckh-Kosmos Verlags GmbH.

- ↑ -. "Aconitum". Natural History Museum.

- ↑ "Atlas Hymenoptera - Atlas of the European Bees - STEP project". atlashymenoptera.net. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Waser, N.M.; Ollerton, J. (2006). Plant-Pollinator Interactions: From Specialization to Generalization. University of Chicago Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780226874005. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Peissel, Michel. 1984. The Ants’ Gold. The Discovery of the Greek El Dorado in the Himalayas. London, Harvill Press, pp. 99-100.

- ↑ Sung, Ying-hsing. T’ien kung k’ai wu. Sung Ying-hsing. 1637. Published as Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century. Translated and annotated by E-tu Zen Sun and Shiou-chuan Sun. 1996. Mineola. New York. Dover Publications, p. 267.

- ↑ Chavannes, Édouard. “Trois Généraux Chinois de la dynastie des Han Orientaux. Pan Tch’ao (32-102 p.C.); – son fils Pan Yong; – Leang K’in (112 p.C.). Chapitre LXXVII du Heou Han chou.”. 1906. T’oung pao 7, pp. 226-227.

- ↑ "A Pacific Eskimo invention in whale hunting in historic times [eScholarship]". escholarship.org. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "RHS Plant Selector - Aconitum × cammarum 'Bicolor'". Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "Aconitum 'Bressingham Spire'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ↑ "Aconitum 'Spark's Variety'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-01-01. Retrieved 2018-01-01.

- 1 2 The Extra Pharmacopoeia Martindale. Vol. 1, 24th edition. London: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1958, page 38.

- 1 2 Chan TY (April 2009). "Aconite poisoning". Clin Toxicol. 47 (4): 279–85. doi:10.1080/15563650902904407. PMID 19514874.

- ↑ Chyka PA, Seger D, Krenzelok EP, Vale JA (2005). "Position paper: Single-dose activated charcoal". Clin Toxicol. 43 (2): 61–87. PMID 15822758.

- ↑ Lin CC, Chan TY, Deng JF (May 2004). "Clinical features and management of herb-induced aconitine poisoning". Ann Emerg Med. 43 (5): 574–9. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.10.046. PMID 15111916.

- ↑ Marija Povšnar; Gordana Koželj; Samo Kreft; Mateja Lumpert (2017). "Rare tradition of the folk medicinal use of Aconitum spp. is kept alive in Solčavsko, Slovenia;". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine.

- ↑ "Aconitum chasmanthum". Iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ "Aconitum heterophyllum". Iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ "Aconitum violaceum". Iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ Wang, Wei; Liu, Yang; Yu, Sheng-Xiang; Gai, Tian-Gang; Chen, Zhi-Duan (21 August 2013). "Gymnaconitum, a new genus of Ranunculaceae endemic to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau" (PDF). Taxon. 62 (4): 713–722. doi:10.12705/624.10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ↑ Grieve, Mrs. Maud (1982) [1931]. Leyel, Mrs. C.F., ed. Aconite, in: A Modern Herbal (Botanical.com; online ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486227987.

- ↑ More, Brookes (1922). "P. Ovidius Naso : Metamorphoses; Book 6, lines 87–145". Perseus Digital Library Project. Boston: Cornhill Publishing Co.

- ↑ Graves, R (1955). "Theseus and Medea". Greek Myths. London: Penguin. pp. 332–336. ISBN 0-14-001026-2.

- ↑ "附子 in English".

- ↑ Karen Brazell; James T. Araki (1998). Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays. Columbia University Press.

- ↑ ""Midsomer Murders" Garden of Death". IMDB.com. 2000. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ Ovid, Metamorphoses 7.406 ff.. The story is first attested by Euphorion of Chalcis, fragment 41 Lightfoot (Lightfoot, pp. 272–275).

- ↑ Rabid: a Cultural History of the World's Most Diabolical Virus by Bill Wasik.

- ↑ Kuehl, BJ. "Count Dracula Original Movie Script". Script-o-rama.com. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ↑ "The Wolf Man, Quotes". IMDb.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ p. 136, Our Lady of the Flowers by Jean Genet, tr. Bernard Frechtman, Grove Press, NYC, 1961

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aconitum. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Aconitum |

- James Grout: Aconite Poisoning, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Photographs of Aconite plants

- Jepson Eflora entry for Aconitum