Willow

| Willow Tree | |

|---|---|

| |

| Salix alba 'Vitellina-Tristis' Morton Arboretum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Treeae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Salicaceae |

| Tribe: | Saliceae[1] |

| Genus: | Salix |

| Type species | |

| Salix alba L. | |

| Species | |

|

About 400.[2] | |

Willows, also called sallows, and osiers, form the genus Salix, around 400 species[2] of deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Most species are known as willow, but some narrow-leaved shrub species are called osier, and some broader-leaved species are referred to as sallow (from Old English sealh, related to the Latin word salix, willow). Some willows (particularly arctic and alpine species) are low-growing or creeping shrubs; for example, the dwarf willow (Salix herbacea) rarely exceeds 6 cm (2.4 in) in height, though it spreads widely across the ground.

Description

Willows all have abundant watery bark sap, which is heavily charged with salicylic acid, soft, usually pliant, tough wood, slender branches, and large, fibrous, often stoloniferous roots. The roots are remarkable for their toughness, size, and tenacity to live, and roots readily sprout from aerial parts of the plant.

The leaves are typically elongated, but may also be round to oval, frequently with serrated edges. Most species are deciduous; semievergreen willows with coriaceous leaves are rare, e.g. Salix micans and S. australior in the eastern Mediterranean. All the buds are lateral; no absolutely terminal bud is ever formed. The buds are covered by a single scale. Usually, the bud scale is fused into a cap-like shape, but in some species it wraps around and the edges overlap.[3] The leaves are simple, feather-veined, and typically linear-lanceolate. Usually they are serrate, rounded at base, acute or acuminate. The leaf petioles are short, the stipules often very conspicuous, resembling tiny, round leaves, and sometimes remaining for half the summer. On some species, however, they are small, inconspicuous, and caducous (soon falling). In color, the leaves show a great variety of greens, ranging from yellowish to bluish color.

Flowers

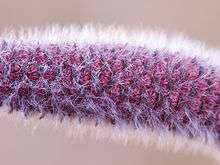

Willows are dioecious, with male and female flowers appearing as catkins on separate plants; the catkins are produced early in the spring, often before the leaves.

The staminate (male) flowers are without either calyx with corolla; they consist simply of stamens, varying in number from two to 10, accompanied by a nectariferous gland and inserted on the base of a scale which is itself borne on the rachis of a drooping raceme called a catkin, or ament. This scale is square, entire, and very hairy. The anthers are rose-colored in the bud, but orange or purple after the flower opens; they are two-celled and the cells open latitudinally. The filaments are threadlike, usually pale brown, and often bald.

The pistillate (female) flowers are also without calyx or corolla, and consist of a single ovary accompanied by a small, flat nectar gland and inserted on the base of a scale which is likewise borne on the rachis of a catkin. The ovary is one-celled, the style two-lobed, and the ovules numerous.

Cultivation

Almost all willows take root very readily from cuttings or where broken branches lie on the ground. The few exceptions include the goat willow (Salix caprea) and peachleaf willow (Salix amygdaloides). One famous example of such growth from cuttings involves the poet Alexander Pope, who begged a twig from a parcel tied with twigs sent from Spain to Lady Suffolk. This twig was planted and throve, and legend has it that all of England's weeping willows are descended from this first one.[4][5]

Willows are often planted on the borders of streams so their interlacing roots may protect the bank against the action of the water. Frequently, the roots are much larger than the stem which grows from them.

Hybrids

Willows are very cross-compatible, and numerous hybrids occur, both naturally and in cultivation. A well-known ornamental example is the weeping willow (Salix × sepulcralis), which is a hybrid of Peking willow (Salix babylonica) from China and white willow (Salix alba) from Europe.

The hybrid cultivar 'Boydii' has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[6]

Ecological issues

Willows are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species, such as the mourning cloak butterfly.[7] Ants, such as wood ants, are common on willows inhabited by aphids, coming to collect aphid honeydew, as sometimes do wasps.

A small number of willow species were widely planted in Australia, notably as erosion-control measures along watercourses. They are now regarded as invasive weeds which occupy extensive areas across southern Australia and are considered 'Weeds of National Significance'. Many catchment management authorities are removing and replacing them with native trees.[8][9]

Substantial research undertaken from 2006 has identified that willows often inhabit an unoccupied niche when they spread across the bed of shallow creeks and streams and if removed, there is a potential water saving of up to 500 mm/per year per hectare of willow canopy area, depending on willow species and climate zone. This water could benefit the environment or provision of local water resources, especially during dry periods.[10][11][12] To aid management of willows, a remote sensing method has been developed to accurately map willow area along and in streams across southern Australia.[13]

Willow roots spread widely and are very aggressive in seeking out moisture; for this reason, they can become problematic when planted in residential areas, where the roots are notorious for clogging French drains, drainage systems, weeping tiles, septic systems, storm drains, and sewer systems, particularly older, tile, concrete, or ceramic pipes. Newer, PVC sewer pipes are much less leaky at the joints, and are therefore less susceptible to problems from willow roots; the same is true of water supply piping.[14][15]

Pests and diseases

Willow species are hosts to more than a hundred aphid species, belonging to Chaitophorus and other genera,[16] forming large colonies to feed on plant juices, on the underside of leaves in particular.[17] Corythucha elegans, the willow lace bug, is a bug species in the family Tingidae found on willows in North America.

Rust, caused by fungi of genus Melampsora, is known to damage leaves of willows, covering them with orange spots.[18]

Uses

Medicinal

The leaves and bark of the willow tree have been mentioned in ancient texts from Assyria, Sumer and Egypt[19] as a remedy for aches and fever,[20] and in Ancient Greece the physician Hippocrates wrote about its medicinal properties in the fifth century BC. Native Americans across the Americas relied on it as a staple of their medical treatments. It provides temporary pain relief. Salicin is metabolized into salicylic acid in the human body, and is a precursor of aspirin.[21] In 1763, its medicinal properties were observed by the Reverend Edward Stone in England. He notified the Royal Society, which published his findings. The active extract of the bark, called salicin, was isolated to its crystalline form in 1828 by Henri Leroux, a French pharmacist, and Raffaele Piria, an Italian chemist, who then succeeded in separating out the compound in its pure state. In 1897, Felix Hoffmann created a synthetically altered version of salicin (in his case derived from the Spiraea plant), which caused less digestive upset than pure salicylic acid. The new drug, formally acetylsalicylic acid, was named Aspirin by Hoffmann's employer Bayer AG. This gave rise to the hugely important class of drugs known as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Manufacturing

Some of humans' earliest manufactured items may have been made from willow. A fishing net made from willow dates back to 8300 BC.[22] Basic crafts, such as baskets, fish traps, wattle fences and wattle and daub house walls, were often woven from osiers or withies (rod-like willow shoots, often grown in coppices). One of the forms of Welsh coracle boat traditionally uses willow in the framework. Thin or split willow rods can be woven into wicker, which also has a long history. The relatively pliable willow is less likely to split while being woven than many other woods, and can be bent around sharp corners in basketry. Willow wood is also used in the manufacture of boxes, brooms, cricket bats, cradle boards, chairmans and other furniture, dolls, flutes, poles, sweat lodges, toys, turnery, tool handles, veneer, wands and whistles. In addition, tannin, fibre, paper, rope and string can be produced from the wood. Willow is also used in the manufacture of double basses for backs, sides and linings, and in making splines and blocks for bass repair.

Other

- Agriculture: Willows produce a modest amount of nectar from which bees can make honey, and are especially valued as a source of early pollen for bees. Poor people at one time often ate willow catkins that had been cooked to form a mash.[23]

- Art: Willow is used to make charcoal (for drawing) and in living sculptures. Living sculptures are created from live willow rods planted in the ground and woven into shapes such as domes and tunnels. Willow stems are used to weave baskets and three-dimensional sculptures, such as animals and figures. Willow stems are also used to create garden features, such as decorative panels and obelisks.

- Energy: Willow is grown for biomass or biofuel, in energy forestry systems, as a consequence of its high energy in-energy out ratio, large carbon mitigation potential and fast growth.[24] Large-scale projects to support willow as an energy crop are already at commercial scale in Sweden.[25] Programs in other countries are being developed through initiatives such as the Willow Biomass Project in the US, and the Energy Coppice Project in the UK.[26] Willow may also be grown to produce charcoal.

- Environment: As a plant, willow is used for biofiltration,[27] constructed wetlands, ecological wastewater treatment systems,[28] hedges, land reclamation, landscaping, phytoremediation,[29] streambank stabilisation (bioengineering), slope stabilisation, soil erosion control, shelterbelt and windbreak, soil building, soil reclamation,[30] tree bog compost toilet, and wildlife habitat.

- Religion: Willow is one of the "Four Species" used ritually during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. In Buddhism, a willow branch is one of the chief attributes of Kwan Yin, the bodhisattva of compassion. Christian churches in northwestern Europe and Ukraine and Bulgaria[31] often used willow branches in place of palms in the ceremonies on Palm Sunday.[32]

Culture

The willow is one of the four species associated with the Jewish festival of Sukkot. Willow branches are also used during the synagogue service on Hoshana Rabbah, the seventh day of Sukkot.

In China, some people carry willow branches with them on the day of their Tomb Sweeping or Qingming Festival. Willow branches are also put up on gates and/or front doors, which they believe help ward off the evil spirits that wander on Qingming. Legend states that on Qingming Festival, the ruler of the underworld allows the spirits of the dead to return to earth. Since their presence may not always be welcome, willow branches keep them away.[33] In traditional pictures of the Goddess of Mercy Guanyin, she is often shown seated on a rock with a willow branch in a vase of water at her side. The Goddess employs this mysterious water and the branch for putting demons to flight. Taoist witches also use a small carving made from willow wood for communicating with the spirits of the dead. The image is sent to the nether world, where the disembodied spirit is deemed to enter it, and give the desired information to surviving relatives on its return.[34] The willow is a famous subject in many East Asian nations' cultures, particularly in pen and ink paintings from China and Japan.

A gisaeng (Korean geisha) named Hongrang, who lived in the middle of the Joseon Dynasty, wrote the poem "By the willow in the rain in the evening", which she gave to her parting lover (Choi Gyeong-chang).[35] Hongrang wrote:

"...I will be the willow on your bedside."

In Japanese tradition, the willow is associated with ghosts. It is popularly supposed that a ghost will appear where a willow grows. Willow trees are also quite prevalent in folklore and myths.[36][37]

In English folklore, a willow tree is believed to be quite sinister, capable of uprooting itself and stalking travellers. The Viminal Hill, one of the Seven Hills of Rome, derives its name from the Latin word for osier, viminia (pl.).

Hans Christian Andersen wrote a story called "Under the Willow Tree" (1853) in which children ask questions of a tree they call "willow-father", paired with another entity called "elder-mother".[38]

"Green Willow" is a Japanese ghost story in which a young samurai falls in love with a woman called Green Willow who has a close spiritual connection with a willow tree.[39] "The Willow Wife" is another, not dissimilar tale.[40] "Wisdom of the Willow Tree" is an Osage Nation story in which a young man seeks answers from a willow tree, addressing the tree in conversation as 'Grandfather'.[41]

The Whomping Willow is featured throughout the Harry Potter series, most notably as a guardian for a backdoor entrance to the Shrieking Shack. This is especially important in the third and seventh installments of the series, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows respectively.

In Central Europe a "hollow willow" is a common figure of speech, alluding to a person one can confide secrets in. The metaphor was used e.g. in the poem Král Lávra (King Lear) by Czech poet Karel Havlíček Borovský (1854).

Willow is considered the national tree of Ukraine.

Selected species

The genus Salix is made up of around 400 species[2] of deciduous trees and shrubs:

- Salix acutifolia Willd. – long-leaved violet willow

- Salix alaxensis (Andersson) Coville

- Salix alba L. – white willow

- Salix amygdaloides Andersson – peachleaf willow

- Salix arbuscula L.

- Salix arbusculoides – littletree willow

- Salix arctica Pall. – Arctic willow

- Salix arizonica Dorn

- Salix atrocinerea Brot. – grey willow

- Salix aurita L. – eared willow

- Salix babylonica L. – Babylon willow, Peking willow or weeping willow

- Salix bakko

- Salix barclayi Andersson

- Salix barrattiana – Barratt's willow

- Salix bebbiana Sarg. – beaked willow, long-beaked willow, and Bebb's willow

- Salix bicolor

- Salix bonplandiana Kunth – Bonpland willow

- Salix boothii Dorn – Booth's willow

- Salix brachycarpa Nutt.

- Salix breweri Bebb – Brewer's willow

- Salix canariensis Chr. Sm.

- Salix candida Flüggé ex Willd. – sageleaf willow

- Salix caprea L. – goat willow, or pussy willow

- Salix caroliniana Michx. – coastal plain willow

- Salix chaenomeloides Kimura

- Salix cinerea L. – grey willow

- Salix cordata Michx. – sand dune willow, furry willow, or heartleaf willow

- Salix delnortensis C.K.Schneid. – Del Norte willow

- Salix discolor Muhl. – American willow

- Salix drummondiana Barratt ex Hook. – Drummond's willow

- Salix eastwoodiae Cockerell ex A.Heller – Eastwood's willow, mountain willow, or Sierra willow

- Salix eleagnos Scop. – olive willow

- Salix eriocarpa

- Salix exigua Nutt. – sandbar willow, narrowleaf willow, or coyote willow

- Salix floridana

- Salix fragilis L. – crack willow

- Salix fuscescens – Alaska bog willow

- Salix futura

- Salix geyeriana Andersson – Geyer's willow

- Salix gilgiana Seemen

- Salix glauca L.

- Salix glaucosericea

- Salix gooddingii C. R. Ball – Goodding's willow, or Goodding's black willow

- Salix gracilistyla Miq.

- Salix hastata L.

- Salix herbacea L. – dwarf willow, least willow or snowbed willow

- Salix hookeriana Barratt ex Hook. – dune willow, coastal willow, or Hooker's willow

- Salix hultenii

- Salix humboldtiana Willd.

- Salix integra Thunb.

- Salix interior

- Salix japonica Thunb.

- Salix jepsonii C.K.Schneid. – Jepson's willow

- Salix jessoensis Seemen

- Salix koriyanagi Kimura ex Goerz

- Salix kusanoi

- Salix laevigata Bebb – red willow or polished willow

- Salix lanata L. – woolly willow

- Salix lapponum L. – downy willow

- Salix lasiolepis Benth. – arroyo willow

- Salix lemmonii Bebb – Lemmon's willow

- Salix libani – Lebanese willow

- Salix ligulifolia C.R.Ball – strapleaf willow

- Salix lucida Muhl. – shining willow, Pacific willow, or whiplash willow

- Salix lutea Nutt. – yellow willow

- Salix magnifica Hemsl.

- Salix matsudana Koidz. – Chinese willow or twisted willow, variant Corkscrew

- Salix melanopsis Nutt. – dusky willow

- Salix miyabeana Seemen

- Salix monticola

- Salix mucronata – Cape silver willow

- Salix microphylla Schltdl. & Cham.

- Salix myrsinifolia Salisb.

- Salix myrtillifolia

- Salix myrtilloides L. – swamp willow

- Salix nakamurana

- Salix nigra Marshall – black willow

- Salix orestera C.K.Schneid. – Sierra willow or gray-leafed Sierra willow

- Salix paradoxa Kunth

- Salix pentandra L. – bay willow

- Salix phylicifolia L.

- Salix pierotii – Korean willow[42]

- Salix planifolia Pursh. – diamondleaf willow or tea-leafed willow

- Salix polaris Wahlenb. – polar willow

- Salix prolixa Andersson – MacKenzie's willow

- Salix pulchra

- Salix purpurea L. – purple willow or purple osier

- Salix reinii

- Salix reticulata L. – net-veined willow

- Salix retusa

- Salix richardsonii

- Salix rorida Lacksch.

- Salix rupifraga

- Salix schwerinii E. L. Wolf

- Salix scouleriana Barratt ex Hook. – Scouler's willow

- Salix sepulcralis group – hybrid willows

- Salix sericea Marshall – silky willow

- Salix serissaefolia

- Salix serissima (L. H. Bailey) Fernald – autumn willow or fall willow

- Salix serpyllifolia

- Salix sessilifolia Nutt. – northwest sandbar willow

- Salix shiraii

- Salix sieboldiana

- Salix sitchensis C. A. Sanson ex Bong. – Sitka willow

- Salix subfragilis

- Salix subopposita Miq.

- Salix taraikensis

- Salix tarraconensis

- Salix taxifolia Kunth – yew-leaf willow

- Salix tetrasperma Roxb. – Indian willow

- Salix triandra L. – almond willow or almond-leaved willow

- Salix udensis Trautv. & C. A. Mey.

- Salix viminalis L. – common osier

- Salix vulpina Andersson

- Salix yezoalpina Koidz.

- Salix yoshinoi

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salix. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Salix |

- Aravah, the Hebrew name of the willow, for its ritual use during the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles

- List of Lepidoptera that feed on willows

- Rhabdophaga rosaria, a willow gall

- Sail, Ogham letter meaning "willow"

- Willow Biomass Project

- Willow water, using the biological rooting hormones indolebutyric acid and salicylic acid from willow branches to stimulate root growth in new cuttings

References

- ↑ "Genus Salix (willows)". Taxonomy. UniProt. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- 1 2 3 Mabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge.

- ↑ George W. Argus. The Genus Salix (Salicaceae) in the Southeastern United States. Systematic Botany Monographs. 9. JSTOR 25027618.

- ↑ Leland, John (2005). Aliens in the Backyard: Plant and Animal Imports Into America. University of South Carolina Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-57003-582-1.

- ↑ Laird, Mark (1999). The Flowering of the Landscape Garden: English Pleasure Grounds, 1720-1800. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 403. ISBN 0-8122-3457-X.

- ↑ "RHS Plant Selector – Salix 'Boydii'". Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "Mourning Cloak". Study of Northern Virginia Ecology. Fairfax County Public Schools.

- ↑ Albury/Wodonga Willow Management Working Group (December 1998). "Willows along watercourses: managing, removing and replacing". Department of Primary Industries, State Government of Victoria.

- ↑ Cremer, Kurt W. (2003). "Introduced willows can become invasive pests in Australia" (PDF).

- ↑ Doody, Tanya; Benyon, Richard (2011). "Quantifying water savings from willow removal in Australian streams". Journal of Environmental Management. 92: 926–935. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.10.061.

- ↑ Doody, Tanya; Nagler, Pamela; Glenn, Edward; Moore, Georgianne; Morino, Kiyomi; Hultine, Kevin; Benyon, Richard (2011). "Potential for water salvage by removal of non-native woody vegetation from dryland river systems". Hydrological Processes. 25 (26): 4117–4131. Bibcode:2011HyPr...25.4117D. doi:10.1002/hyp.8395.

- ↑ Doody, Tanya; Benyon, Richard; Theiveyanathan, S; Koul, Vijay; Stewart, Leroy (2013). "Development of pan coefficients for estimating evapotranspiration from woody vegetation". Hydrological Processes. 28 (4): 2129–2149. Bibcode:2014HyPr...28.2129D. doi:10.1002/hyp.9753.

- ↑ Doody, Tanya; Lewis, Megan; Benyon, Richard; Byrne, Guy (2013). "A method to map riparian exotic vegetation (Salix spp.) area to inform water resource management". Hydrological Processes. 28 (11): 3809–3823. Bibcode:2014HyPr...28.3809D. doi:10.1002/hyp.9916.

- ↑ Salix spp. UFL/edu, Weeping Willow Fact Sheet ST-576, Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson, United States Forest Service

- ↑ "Rooting Around: Tree Roots", Dave Hanson, Yard & Garden Line News Volume 5 Number 15, University of Minnesota Extension, 1 October 2003

- ↑ Blackman, R. L.; Eastop, V. F. (1994). Aphids on the World's Trees. CABI. ISBN 9780851988771.

- ↑ David V. Alford (2012). Pests of Ornamental Trees, Shrubs and Flowers. p. 78. ISBN 9781840761627.

- ↑ Kenaley, Shawn C.; et al. (2010). "Leaf Rust" (PDF).

- ↑ James Breasted (English translation). "The Edwin Smith Papyrus". Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ↑ "An aspirin a day keeps the doctor at bay: The world's first blockbuster drug is a hundred years old this week". Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ↑ W. Hale White. "Materia Medica Pharmacy, Pharmacology and Therapeutics". Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- ↑ The palaeoenvironment of the Antrea Net Find The Department of Geography, University of Helsinki

- ↑ Hageneder, Fred (2001). The Heritage of Trees. Edinburgh : Floris. ISBN 0-86315-359-3. p.172

- ↑ Aylott, Matthew J.; Casella, E; Tubby, I; Street, NR; Smith, P; Taylor, G (2008). "Yield and spatial supply of bioenergy poplar and willow short-rotation coppice in the UK" (PDF). New Phytologist. 178 (2): 358–370. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02396.x. PMID 18331429. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ↑ Mola-Yudego, Blas; Aronsson, Pär. (2008). "Yield models for commercial willow biomass plantations in Sweden". Biomass and Bioenergy. 32 (9): 829–837. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2008.01.002.

- ↑ "Forestresearch.gov.uk". Forestresearch.gov.uk. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ↑ Guidi Nissim W., Jerbi A., Lafleur B., Fluet R., Labrecque M. (2015) "Willows for the treatment of municipal wastewater: long-term performance under different irrigation rates". Ecological Engineering 81: 395–404. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.04.067.

- ↑ Guidi Nissim W., Voicu A., Labrecque M. (2014) "Willow short-rotation coppice for treatment of polluted groundwater". Ecological Engineering, 62:102–114 doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.10.005.

- ↑ Guidi W., Kadri H., Labrecque L. (2012) "Establishment techniques to using willow for phytoremediation on a former oil refinery in southern-Quebec: achievements and constraints". Chemistry and Ecology, 28(1):49–64. doi:10.1080/02757540.2011.627857

- ↑ Guidi Nissim W., Palm E., Mancuso S., Azzarello E. (2018) "Trace element phytoextraction from contaminated soil: a case study under Mediterranean climate". Environmental Science and Pollution Research, accepted doi:10.1007/s11356-018-1197-x

- ↑ See Palm Sunday#Bulgaria

- ↑ "ChurchYear.net". ChurchYear.net. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ↑ Doolittle, Justus (2002) [1876]. Social Life of the Chinese. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7103-0753-8.

- ↑ Doré S.J., Henry; Kennelly, S.J. (Translator), M. (1914). Researches into Chinese Superstitions. Tusewei Press, Shanghai. Vol I p. 2

- ↑ "The Forest of Willows in Our Minds". Arirang TV. 20 August 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ↑ "In Worship of Trees by George Knowles: Willow".

- ↑ "Mythology and Folklore of the Willow".

- ↑ "Under The Willow Tree". Hca.gilead.org.il. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ↑ "Green Willow". Spiritoftrees.org. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ↑ The Willow Wife Archived 18 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Wisdom of the Willow Tree". Tweedsblues.net. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ↑ English Names for Korean Native Plants (PDF). Pocheon: Korea National Arboretum. 2015. p. 617. ISBN 978-89-97450-98-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2016 – via Korea Forest Service.

Bibliography

- Keeler, Harriet L. (1990). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scriber's Sons. Pages 393–395. ISBN 0-87338-838-0.

- Newsholme, C. (1992). Willows: The Genus Salix. ISBN 0-88192-565-9

- Warren-Wren, S.C. (1992). The Complete Book of Willows. ISBN 0-498-01262-X

- Sviatlana Trybush, Šárka Jahodová, William Macalpine and Angela Karp. (2008). A genetic study of a Salix germplasm resource reveals new insights into relationships among subgenera, sections and species BioEnergy Research. 1(1):67 – 79.

External links

| Look up withy or osier in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up willow, sallow, withy, or osier in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |