Corporal punishment

| Part of a series on |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

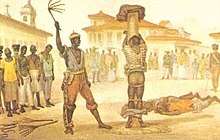

Corporal punishment or physical punishment is a punishment intended to cause physical pain on a person. It is most often practised on minors, especially in home and school settings. Common methods include spanking or paddling. It has also historically been used on adults, particularly on prisoners and enslaved people. Other common methods include flagellation and caning.

Official punishment for crime by inflicting pain or injury, including flogging, branding and even mutilation, was practised in most civilizations since ancient times. However, with the growth of humanitarian ideals since the Enlightenment, such punishments were increasingly viewed as inhumane. By the late 20th century, corporal punishment had been eliminated from the legal systems of most developed countries.[1]

The legality in the 21st century of corporal punishment in various settings differs by jurisdiction. Internationally, the late 20th century and early 21st century saw the application of human rights law to the question of corporal punishment in a number of contexts:

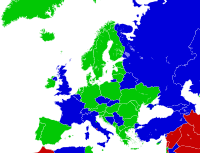

- Corporal punishment in the home, punishment of children or teenagers by parents or other adult guardians— is legal in most of the world. 58 countries, most of them in Europe and Latin America, have banned the practice as of 2018.[2]

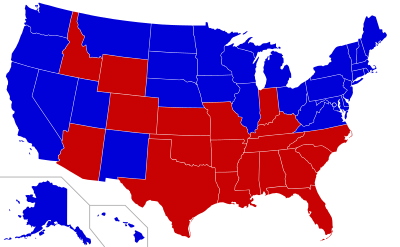

- School corporal punishment—of students by teachers or school administrators—has been banned in many countries, including Canada, Kenya, South Africa, New Zealand and all of Europe. It remains legal, if increasingly less common, in some states of the United States.

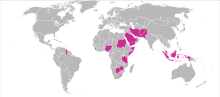

- Judicial corporal punishment, as part of a criminal sentence ordered by a court of law, has long disappeared from European countries.[3] However, as of November 2017, it remains lawful in parts of Africa, Asia, the Anglophone Caribbean and indigenous communities of Ecuador and Colombia.[4] Closely related is prison corporal punishment or disciplinary corporal punishment, ordered by prison authorities or carried out directly by staff. Corporal punishment is also allowed in some military settings in a few jurisdictions.

Other uses of corporal punishment have existed, for instance, as once practised on apprentices by their masters. In many Western countries, medical and human-rights organizations oppose corporal punishment of children. Campaigns against corporal punishment have aimed to bring about legal reform to ban the use of corporal punishment against minors in homes and schools.

Western history

Corporal punishment of children has traditionally been used in the Western world by adults in authority roles.[5] Beating one's child as a punishment was recommended as early as c. the 10th century BC in the book of Proverbs attributed to Solomon:

He that spareth the rod, hateth his son; but he that loveth him, chasteneth him betimes. (Proverbs, XIII, 24)

A fool's lips enter into contention, and his mouth calleth for strokes. (Proverbs, XVIII, 6) Chasten thy son while there is hope, and let not thy soul spare for his crying. (Proverbs, XIX, 18) Judgements are prepared for scorners, and stripes for the backs of fools. (Proverbs, XIX, 29) Foolishness is bound in the heart of a child; but the rod of correction shall drive it from him. (Proverbs, XXII, 15) Withhold not correction from the child; for if thou beatest him with a rod, thou shalt deliver his soul from hell. (Proverbs, XXIII, 13-14) A whip for a horse, a bridle for an ass, and a rod for a fool's back. (Proverbs, XXIX, 15)[6]

Robert McCole Wilson argues, "Probably this attitude comes, at least in part, from the desire in the patriarchal society for the elder to maintain his authority, where that authority was the main agent for social stability. But these are the words that not only justified the use of physical punishment on children for over a thousand years in Christian communities, but ordered it to be used. The words were accepted with but few exceptions; it is only in the last two hundred years that there has been a growing body of opinion that differed. Curiously, the gentleness of Christ towards children (Mark, X) was usually ignored".[7]

Corporal punishment was used in Greece, Rome, and Egypt for both judicial and educational discipline.[8] Some states gained a reputation for using such punishments cruelly; Sparta, in particular, used them as part of a disciplinary regime designed to build willpower and physical strength.[9] Although the Spartan example was extreme, corporal punishment was possibly the most frequent type of punishment. In the Roman Empire, the maximum penalty that a Roman citizen could receive under the law was 40 "lashes" or "strokes" with a whip applied to the back and shoulders, or with the "fasces" (similar to a birch rod, but consisting of 8–10 lengths of willow rather than birch) applied to the buttocks. Such punishments could draw blood, and were frequently inflicted in public.

Quintilian (c. 35 – c. 100) voiced some opposition to the use of corporal punishment. According to Robert McCole Wilson, "probably no more lucid indictment of it has been made in the succeeding two thousand years".[9]

By that boys should suffer corporal punishment, though it is received by custom, and Chrysippus makes no objection to it, I by no means approve; first, because it is a disgrace, and a punishment fit for slaves, and in reality (as will be evident if you imagine the age change) an affront; secondly, because, if a boy's disposition be so abject as not to be amended by reproof, he will be hardened, like the worst of slaves, even to stripes; and lastly, because, if one who regularly exacts his tasks be with him, there will not be the need of any chastisement (Quintilian, Institutes of Oratory, 1856 edition, I, III).[9]

Plutarch, also in the first century, writes:

This also I assert, that children ought to be led to honourable practices by means of encouragement and reasoning, and most certainly not by blows or ill-treatment, for it surely is agreed that these are fitting rather for slaves than for the free-born; for so they grow numb and shudder at their tasks, partly from the pain of the blows, partly from the degradation.[10]

In Medieval Europe, corporal punishment was encouraged by the attitudes of the medieval church towards the human body, flagellation being a common means of self-discipline. This had an influence on the use of corporal punishment in schools, as educational establishments were closely attached to the church during this period. Nevertheless, corporal punishment was not used uncritically; as early as the eleventh century Saint Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury was speaking out against what he saw as the excessive use of corporal punishment in the treatment of children.[11]

From the 16th century onwards, new trends were seen in corporal punishment. Judicial punishments were increasingly turned into public spectacles, with public beatings of criminals intended as a deterrent to other would-be offenders. Meanwhile, early writers on education, such as Roger Ascham, complained of the arbitrary manner in which children were punished.[12]

Peter Newell writes that perhaps the most influential writer on the subject was the English philosopher John Locke, whose Some Thoughts Concerning Education explicitly criticised the central role of corporal punishment in education. Locke's work was highly influential, and may have helped influence Polish legislators to ban corporal punishment from Poland's schools in 1783, the first country in the world to do so.[13]

.png)

During the 18th century, the concept of corporal punishment was challenged by some philosophers and legal reformers. Merely inflicting pain was seen as an inefficient form of discipline, influencing the subject only for a short period of time and effecting no permanent change in their behaviour. Some believed that the purpose of punishment should be reformation, not retribution. This is perhaps best expressed in Jeremy Bentham's idea of a panoptic prison, in which prisoners were controlled and surveyed at all times, perceived to be advantageous in that this system supposedly reduced the need of measures such as corporal punishment.[14]

.jpg)

A consequence of this mode of thinking was a reduction in the use of corporal punishment in the 19th century in Europe and North America. In some countries this was encouraged by scandals involving individuals seriously hurt during acts of corporal punishment. For instance, in Britain, popular opposition to punishment was encouraged by two significant cases, the death of Private Frederick John White, who died after a military flogging in 1846,[15] and the death of Reginald Cancellor, killed by his schoolmaster in 1860.[16] Events such as these mobilised public opinion and, by the late nineteenth century, the extent of corporal punishment's use in state schools was unpopular with many parents in England.[17] Authorities in Britain and some other countries introduced more detailed rules for the infliction of corporal punishment in government institutions such as schools, prisons and reformatories. By the First World War, parents' complaints about disciplinary excesses in England had died down, and corporal punishment was established as an expected form of school discipline.[17]

In the 1870s, courts in the United States overruled the common-law principle that a husband had the right to "physically chastise an errant wife".[18] In the UK the traditional right of a husband to inflict moderate corporal punishment on his wife in order to keep her "within the bounds of duty" was similarly removed in 1891.[19][20] See Domestic violence for more information.

In the United Kingdom, the use of judicial corporal punishment declined during the first half of the 20th century and it was abolished altogether in the Criminal Justice Act, 1948 (zi & z2 GEo. 6. CH. 58.), whereby whipping and flogging were outlawed except for use in very serious internal prison discipline cases,[21] while most other European countries had abolished it earlier. Meanwhile, in many schools, the use of the cane, paddle or tawse remained commonplace in the UK and the United States until the 1980s. In several other countries, it still is: see School corporal punishment.

Among hunter-gatherer tribes

Author Jared Diamond writes that hunter-gatherer societies have tended to use little corporal punishment whereas agricultural and industrial societies tend to use progressively more of it. Diamond suggests this may be because hunter-gatherers tend to have few valuable physical possessions, and misbehavior of the child would not cause harm to others' property.[22]

Researchers living among the Parakanã and Ju/’hoansi people, as well as among some Aboriginal Australians, have written of the absence of physical punishment of children in those cultures.[23]

Wilson writes:

Probably the only generalization that can be made about the use of physical punishment among primitive tribes is that there was no common procedure [...] Pettit concludes that among primitive societies corporal punishment is rare, not because of the innate kindliness of these people but because it is contrary to developing the type of individual personality they set up as their ideal [...] An important point to be made here is that we cannot state that physical punishment as a motivational or corrective device is 'innate' to man.[24]

International treaties

Human rights

Key developments related to corporal punishment occurred in the late 20th century. Years with particular significance to the prohibition of corporal punishment are emphasised.

- 1950: European Convention of Human Rights, Council of Europe.[25] Article 3 bars "inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment".

- 1978: European Court of Human Rights, overseeing its implementation, rules that judicial birching of a juvenile breaches Article 3.[26]

- 1985: Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice, or Beijing Rules, United Nations (UN). Rule 17.3: "Juveniles shall not be subject to corporal punishment."

- 1990 Supplement: Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty. Rule 67: "...all disciplinary measures constituting cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment shall be strictly prohibited, including corporal punishment..."

- 1990: Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency, the Riyadh Guidelines, UN. Paragraph 21(h): education systems should avoid "harsh disciplinary measures, particularly corporal punishment."

- 1966: International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, UN, with currently 167 parties, 74 signatories.[27] Article 7: "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment..."

- 1992: Human Rights Committee, overseeing its implementation, comments: "the prohibition must extend to corporal punishment . . . in this regard . . . article 7 protects, in particular, children, . . .."[28]

- 1984: Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, UN, with currently 150 parties and 78 signatories.[29]

- 1996: Committee Against Torture, overseeing its implementation, condemns corporal punishment.[30]

- 1966: International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN, with currently 160 parties, and 70 signatories.[31] Article 13(1): "education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity..."

- 1999: Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, overseeing its implementation, comments: "corporal punishment is inconsistent with the fundamental guiding principle of international human rights law . . . the dignity of the individual."[32]

- 1961: European Social Charter, Council of Europe.

- 2001: European Committee of Social Rights, overseeing its implementation, concludes: it is not "acceptable that a society which prohibits any form of physical violence between adults would accept that adults subject children to physical violence."[33]

Children's rights

The notion of children’s rights in the Western world developed in the 20th century, but the issue of corporal punishment was not addressed generally before mid-century. Years with particular significance to the prohibition of corporal punishment of children are emphasised.

- 1923: Children's Rights Proclamation by Save the Children founder. (5 articles).

- 1924 Adopted as the World Child Welfare Charter, League of Nations (non-enforceable).

- 1959: Declaration of the Rights of the Child, (UN) (10 articles; non-binding).

- 1989: Convention on the Rights of the Child, UN (54 articles; binding treaty), with currently 193 parties and 140 signatories.[34] Article 19.1: "States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation . . . ."

- 2006: Committee on the Rights of the Child, overseeing its implementation, comments: there is an "obligation of all States Party to move quickly to prohibit and eliminate all corporal punishment."[35]

- 2011: Optional Protocol on a Communications Procedure allowing individual children to submit complaints regarding specific violations of their rights.[36]

- 2006: Study on Violence against Children presented by Independent Expert for the Secretary-General to the UN General Assembly.[37]

- 2007: Post of Special Representative of the Secretary-General on violence against children established.[38]

Modern use

Corporal punishment of minors in the United States

Legal status

58 countries, most of them in Europe and Latin America, have prohibited any corporal punishment of children.

The earliest recorded attempt to prohibit corporal punishment of children by a state dates back to Poland in 1783.[39]:31–2 However, its prohibition in all spheres of life – in homes, schools, the penal system and alternative care settings – occurred first in 1966 in Sweden. The 1979 Swedish Parental Code reads: "Children are entitled to care, security and a good upbringing. Children are to be treated with respect for their person and individuality and may not be subjected to corporal punishment or any other humiliating treatment."[39]:32

As of 2018, corporal punishment of children by parents (or other adults) is outlawed in all settings in 54 nations and 3 constituent nations.[2] States that have completely prohibited corporal punishment of children are listed below (in chronological order):[2]

|

|

|

|

|

|

For a more detailed overview of the global use and prohibition of the corporal punishment of children, see the following table.

| Home | Schools | Penal system | Alternative care settings | ||

| As sentence for crime | As disciplinary measure | ||||

| Prohibited | 54 | 118 | 155 | 116 | 38 |

| Not prohibited | 140 | 80 | 42 | 78 | 160 |

| Legality unknown | - | - | 1 | 4 | - |

Corporal punishment in the home

Domestic corporal punishment, i.e. the punishment of children by their parents, is often referred to colloquially as "spanking", "smacking" or "slapping."

It has been outlawed in an increasing number of countries, starting with Sweden in 1966.[42][2] In some other countries, corporal punishment is legal, but restricted (e.g. blows to the head are outlawed, implements may not be used, only children within a certain age range may be spanked).

In all states of the United States and most African and Asian nations, corporal punishment by parents is currently legal. It is also legal to use certain implements such as a belt or paddle.

In Canada, spanking by parents or legal guardians (but nobody else) is legal, as long as the child is not under 2 years or at least 12 years of age, and no implement other than an open, bare hand is used (belts, paddles, etc. are strictly prohibited). It is also illegal to strike the head when disciplining a child.[43][44]

In the UK, spanking or smacking is legal, but it must not cause an injury amounting to Actual Bodily Harm (any injury such as visible bruising, breaking of the whole skin etc.); in addition, in Scotland, since October 2003, it has been illegal to use any implements or to strike the head when disciplining a child, and it is also prohibited to use corporal punishment towards children under the age of 3 years.

In Pakistan, Section 89 of Pakistan Penal Code allows corporal punishment.[45]

Corporal punishment in schools

Corporal punishment in schools for misbehaviour has been outlawed in many countries. It often involves striking the student on the buttocks or the palm of the hand with an implement kept for the purpose such as a rattan cane or spanking paddle, or with the open hand. There may be restrictions in some jurisdictions, for example, in Singapore caning is permitted for boys only. Medical professionals have urged putting an end to the practice, noting the danger of injury to children's hands especially.[46] In India, corporal punishment has been abolished by law. However, corporal punishment continues to exist and be practised in many Indian schools. Cultural perception of corporal punishment has rarely been studied and researched. One study carried out by Arijit Ghosh and Madhumathi Pasupathi discusses how corporal punishment is perceived among parents and students in the Indian context, with the help of a representative sample size.[47]

Judicial or quasi-judicial punishment

Around 33 countries in the world still retain judicial corporal punishment, including a number of former British territories such as Botswana, Malaysia, Singapore and Tanzania. In Singapore, for certain specified offences, males are routinely sentenced to caning in addition to a prison term. The Singaporean practice of caning became much discussed around the world in 1994 when American teenager Michael P. Fay received four strokes of the cane for vandalism. Judicial caning and whipping are also used in Aceh Province in Indonesia.[48]

A number of other countries with an Islamic legal system, such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Sudan and some northern states in Nigeria, employ judicial whipping for a range of offences. As of 2009, some regions of Pakistan are experiencing a breakdown of law and government, leading to a reintroduction of corporal punishment by ad hoc Islamicist courts.[49] As well as corporal punishment, some Islamic countries such as Saudi Arabia and Iran use other kinds of physical penalties such as amputation or mutilation.[50][51][52] However, the term "corporal punishment" has since the 19th century usually meant caning, flagellation or bastinado rather than those other types of physical penalty.[53][54][55][56][57][58][59]

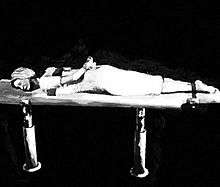

In some countries foot whipping (bastinado) is still practised on prisoners.[60]

Ritual and punishment

In parts of England, boys were once beaten under the old tradition of "Beating the Bounds" whereby a boy was paraded around the edge of a city or parish and spanked with a switch or cane to mark the boundary.[61] One famous "Beating the Bounds" took place around the boundary of St Giles and the area where Tottenham Court Road now stands in central London. The actual stone that marked the boundary is now underneath the Centre Point office tower.[62]

In popular culture

Art

- The Flagellation, (c.1455-70), by Piero della Francesca. Christ is lashed while Pontius Pilate looks on.

- The Whipping, (1941), by Horace Pippin. A figure tied to a whipping post is flogged.[63]

Film and TV

See: List of films and TV containing corporal punishment scenes.

See also

References

- ↑ "Corporal punishment". Encyclopædia Britannica. 9 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "States which have prohibited all corporal punishment". www.endcorporalpunishment.org. Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ↑ http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/assets/pdfs/legality-tables/Europe-and-Central-Asia-progress-table-commitment.pdf

- ↑ http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/legality-tables/ Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children

- ↑ Rich, John M. (December 1989). "The Use of Corporal Punishment". The Clearing House, Vol. 63, No. 4, pp. 149-152.

- ↑ Wilson, Robert M. (1971). A Study of Attitudes Towards Corporal Punishment as an Educational Procedure From the Earliest Times to the Present (Thesis). University of Victoria. 2.3. OCLC 15767752.

- ↑ Wilson (1971), 2.3.

- ↑ Wilson (1971), 2.3–2.6.

- 1 2 3 Wilson (1971), 2.5.

- ↑ Plutarch, Moralia. The Education of Children, Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press, 1927.

- ↑ Wicksteed, Joseph H. The Challenge of Childhood: An Essay on Nature and Education, Chapman & Hall, London, 1936, pp. 34–35. OCLC 3085780

- ↑ Ascham, Roger. The scholemaster, John Daye, London, 1571, p. 1. Republished by Constable, London, 1927. OCLC 10463182

- ↑ Newell, Peter (ed.). A Last Resort? Corporal Punishment in Schools, Penguin, London, 1972, p. 9. ISBN 0-14-080698-9

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy. Chrestomathia (Martin J. Smith and Wyndham H. Burston, eds.), Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1983, pp. 34, 106. ISBN 0-19-822610-1

- ↑ Barretts, C.R.B. The History of The 7th Queen's Own Hussars Vol. II Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Middleton, Jacob (2005). "Thomas Hopley and mid-Victorian attitudes to corporal punishment". History of Education.

- 1 2 Middleton, Jacob (November 2012). "Spare the Rod". History Today (London).

- ↑ Calvert, R. "Criminal and civil liability in husband-wife assaults", in Violence in the family (Suzanne K. Steinmetz and Murray A. Straus, eds.), Harper & Row, New York, 1974. ISBN 0-396-06864-2

- ↑ R. v Jackson Archived 7 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine., [1891] 1 QB 671, abstracted at LawTeacher.net.

- ↑

- ↑ Criminal Justice Act, 1948 zi & z2 GEo. 6. CH. 58., pp. 54-55.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared (2013). The World Until Yesterday. Viking. Ch. 5. ISBN 978-1-101-60600-1.

- ↑ Gray, Peter (2009). "Play as a Foundation for Hunter-Gatherer Social Existence". American Journal of Play. 1 (4): 476–522.

- ↑ Wilson (1971), 2.1.

- ↑ This applies to the 47 members of the Council of Europe, an entirely separate body from the European Union, which has only 28 member states.

- ↑ Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children (2012). Retrieved 1 May 2012. "Key Judgements." The ruling concerned the Isle of Man, a UK Crown Dependency.

- ↑ UN (2012) "4 . International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Archived 1 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine.," United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ UN Human Rights Committee (1992) "General Comment No. 20". HRI/GEN/1/Rev.4.: p. 108

- ↑ UN (2012) "9 . Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Archived 8 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ UN (1996) General Assembly Official Records, Fiftieth Session, A/50/44, 1995: par. 177, and A/51/44, 1996: par. 65(i).

- ↑ UN (2012). 3. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Archived 17 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1999) "General Comment on 'The Right to Education'," HRI/GEN/1/Rev.4: 73.

- ↑ European Committee of Social Rights 2001. "Conclusions XV – 2," Vol. 1.

- ↑ UN (2012). 11. Convention on the Rights of the Child Archived 11 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.. United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (2006) "General Comment No. 8:" par. 3. However, Article 19 of the Convention makes no reference to corporal punishment, and the Committee's interpretation on this point has been explicitly rejected by several States Party to the Convention, including Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom.

- ↑ UN OHCHR (2012). Committee on the Rights of the Child. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ UN (2006) "Study on Violence against Children presented by Independent Expert for the Secretary-General". United Nations, A/61/299. See further: UN (2012e). Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence against Children. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ UN (2007) United Nations General Assembly, A/RES/62/141. The United States was the only country to vote against. There were no abstentions.

- 1 2 Abolishing corporal punishment of children : questions and answers (PDF). Strasbourg: Council of Europe. 2007. ISBN 978-9-287-16310-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2014.

- ↑ https://www.crin.org/en/library/news-archive/chile-proposed-child-abuse-law-falls-short-banning-corporal-punishment

- ↑ http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/news/10/2017/aruba-has-prohibited-all-corporal-punishment-of-children.html

- ↑ "The Swedish Ban on Corporal Punishment: Its History and Effects". www.nospank.net. line feed character in

|title=at position 40 (help) - ↑ "To spank or not to spank?". CBC News. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ↑ Barnett, Laura. "The "Spanking" Law: Section 43 of the Criminal Code". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ↑ Wajeeh, Ul Hassan. "Pakistan Penal Code (Act XLV of 1860)". Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ↑ "Corporal Punishment to Children's Hands", A Statement by Medical Authorities as to the Risks, January 2002.

- ↑ Ghosh, Arijit; University, VIT; Vellore; Nadu, Tamil; India; Pasupathi, Madhumathi; University, VIT; Vellore; Nadu, Tamil (18 August 2016). "Perceptions of Students and Parents on the Use of Corporal Punishment at Schools in India" (PDF). Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities. 8 (3): 269–280. doi:10.21659/rupkatha.v8n3.28.

- ↑ McKirdy, Euan (14 July 2018). "Gay men, adulterers publicly flogged in Aceh, Indonesia". CNN. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ↑ Walsh, Declan. "Video of girl's flogging as Taliban hand out justice", The Guardian, London, 2 April 2009.

- ↑ Campaign against the Arms Trade, Evidence to the House of Commons Select Committee on Foreign Affairs, London, January 2005.

- ↑ "Lashing Justice", Editorial, The New York Times, 3 December 2007.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia: Court Orders Eye to Be Gouged Out", Human Rights Watch, 8 December 2005.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1989, "corporal punishment: punishment inflicted on the body; originally including death, mutilation, branding, bodily confinement, irons, the pillory, etc. (as opposed to a fine or punishment in estate or rank). In 19th c. usually confined to flogging or similar infliction of bodily pain."

- ↑ "Physical punishment such as caning or flogging" – Concise Oxford Dictionary.

- ↑ "... inflicted on the body, esp. by beating." – Oxford American Dictionary of Current English.

- ↑ "mostly a euphemism for the enforcement of discipline by applying canes, whips or birches to the buttocks." – Charles Arnold-Baker, The Companion to British History, Routledge, 2001.

- ↑ "Physical punishment such as beating or caning" – Chambers 21st Century Dictionary.

- ↑ "Punishment of a physical nature, such as caning, flogging, or beating." – Collins English Dictionary.

- ↑ "the striking of somebody's body as punishment" – Encarta World English Dictionary, MSN. Archived 31 October 2009.

- ↑ "Confirming Torture: The Use of Imaging in Victims of Falanga". Forensic Magazine. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ "Mayor may axe child spanking rite", BBC News Online, 21 September 2004.

- ↑ Ackroyd, Peter. London: The Biography, Chatto & Windus, London, 2000. ISBN 1-85619-716-6

- ↑ [www.reynoldahouse.org/collections/object/the-whipping]| Reynolda House Museum of American Art

Further reading

- Barathan, Gopal; The Caning of Michael Fay, (1995). A contemporary account of an American teenager ( Michael P. Fay ) caned for vandalism in Singapore.

- Gates, Jay Paul and Marafioti, Nicole; (eds.), Capital and Corporal Punishment in Anglo-Saxon England, (2014). Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.

- Moskos, Peter; In Defence of Flogging, (2011). An argument that flogging might be better than jail time.

- Scott, George; A History of Corporal Punishment, (1996).

External links

- "Spanking" (Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance)

- Center for Effective Discipline (USA)

- World Corporal Punishment Research

- Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children