Vienne, Isère

Vienne (French: [vjɛn] (![]()

Vienne Vièna (Arpitan) | |

|---|---|

Subprefecture and commune | |

An aerial view of Vienne | |

Coat of arms | |

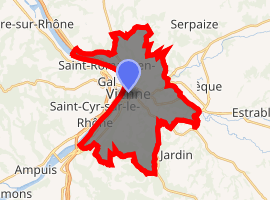

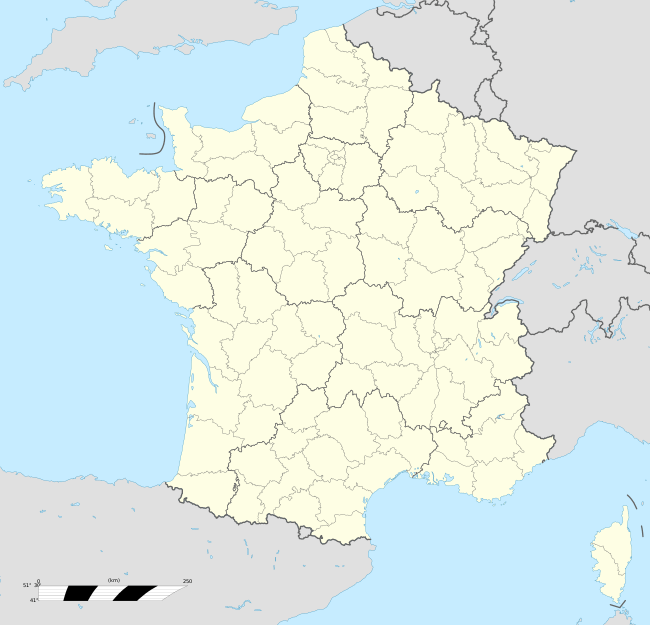

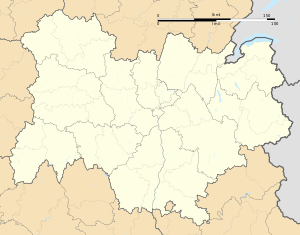

Location of Vienne

| |

Vienne  Vienne | |

| Coordinates: 45°31′27″N 4°52′41″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes |

| Department | Isère |

| Arrondissement | Vienne |

| Canton | Vienne-1 and 2 |

| Intercommunality | Pays Viennois |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2014–2020) | Thierry Kovacs (UMP) |

| Area 1 | 22.65 km2 (8.75 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 29,306 |

| • Density | 1,300/km2 (3,400/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Viennois |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 38544 /38200 |

| Elevation | 140–404 m (459–1,325 ft) (avg. 169 m or 554 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Before the arrival of the Roman armies, Vienne was the capital city of the Allobroges, a Gallic people. Transformed into a Roman colony in 47 BC under Julius Caesar, Vienne became a major urban center, ideally located along the Rhône, then a major axis of communication. Emperor Augustus banished Herod the Great's son, the ethnarch Herod Archelaus to Vienne in 6 AD.[2]

The town became a Roman provincial capital and remains of Roman constructions are everywhere in modern Vienne. The town was also an important early bishopric in Christian Gaul. Its most famous bishop was Avitus of Vienne. At the Council of Vienne, convened there in October 1311, Pope Clement V abolished the order of the Knights Templar. During the Middle Ages, Vienne was part of the kingdom of Provence, dependent on the Holy Roman Empire, while the opposite bank of the Rhône was French territory, thus making it a strategic position.[3]

Today the town is a regional commercial and industrial center, known regionally for its Saturday market. A Roman temple, circus pyramid, and theatre (where the annual Jazz à Vienne is held), as well as museums (archaeological, textile industry) and notable Catholic buildings, make tourism an important part of the town's economy.

History

.jpg)

Roman Vienne

The oppidum of the Allobroges became a Roman colony about 47 BC under Julius Caesar, but the Allobroges managed to expel them; the exiles then founded the colony of Lugdunum (today's Lyon).[3] Ethnarch of Judea Herod Archelaus was exiled here in 6 AD.[4] During the early Empire, Vienna (as the Romans called it—not to be confused with today's Vienna, then known as Vindobona) regained all its former privileges as a Roman colony. In 260 Postumus was proclaimed emperor here of a short-lived Gallo-Roman empire. Later it became a provincial capital of the Dioecesis Viennensis. Vienne became the seat of the vicar of prefects after the creation of regional dioceses. Regional dioceses were created during the First Tetrarchy, 293-305, or possibly later as some recent studies suggest in 313, but no later than the Verona List securely dated to June 314.[5] The date of creation is still controversial.

On the bank of the Gère are traces of the ramparts of the old Roman city, and on Mont Pipet (east of the town) are the remains of a Roman theatre, while the ruined thirteenth-century castle there was built on Roman footings. Several ancient aqueducts and traces of Roman roads can still be seen.

Two important Roman monuments still stand at Vienne. One is the Early Imperial Temple of Augustus and Livia, a rectangular peripteral building of the Corinthian order, erected by the emperor Claudius, which owes its survival, like the Maison Carrée at Nîmes, to being converted to a church soon after the Theodosian decrees and later rededicated as "Notre Dame de Vie." (During the Revolutionary Reign of Terror it was used for the local Festival of Reason.) The other is the Plan de l'Aiguille, a truncated pyramid resting on a portico with four arches, from the Roman circus. Legends from the 13th century mention Pontius Pilate's death in Vienne. Later legends held that the pyramid was either the tomb of Herod Archelaus or of Pontius Pilate.[6]

The vestiges of a temple to Cybèle were discovered in 1945 when a new hospital was built on Mount Salomon and the Ancien Hôpital in the center of town was torn down. Subsequent archaeological research conducted in 1965 permitted detailed reconstruction of the floor plan for the temple as well as the surrounding forum and established that the temple was constructed in the first century AD.[7]

Christian Vienne

The provincial capital was an important early seat of a bishop and the legendary first bishop said to have been Crescens, a disciple of Paul. There were Christians here in 177 when the churches of Vienne and Lyon addressed a letter to those of Asia and Phrygia and mention is made of the deacon of Vienne (Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History). The first historical bishop was Verus, who was present at the Council of Arles (314). About 450, Vienne's bishops became archbishops,several of whom in the played an important cultural role, e.g. Mamertus, who established Rogation pilgrimages, and the poet, Avitus (498-518). Vienne's archbishops and those of Lyon disputed the title of "Primate of All the Gauls" based on the dates of founding of the cities compared to the dates of founding of the bishoprics.[3] Vienne's archbishopric was suppressed in 1790[3] during the revolution and officially terminated 11 years later by the Concordat of 1801.

Burgundian Vienne

Vienne was a target during the Migration Period: it was taken by the Kingdom of the Burgundians in 438, but re-taken by the Romans and held until 461. In 534 the Merovingian-led Franks captured Vienne. It was then sacked by the Lombards in 558, and later by the Moors in 737.[3] When Francia's king divided Frankish Burgundia into three parts in 843 by the Treaty of Verdun, Vienne became part of Middle Francia.

In the Kingdom of Provence

King Charles II the Bald assigned the district in 869 to Comte Boso of Provence, who in 879 proclaimed himself king of Provence and on his death in 887 was buried in the cathedral church of St. Maurice.[3] Vienne then continued as capital of the Dauphiné Vienne of the Kingdom of Provence, from 882 of the Kingdom of West Francia and from 933 of the Kingdom of Arles until in 1032, when it reverted to the Holy Roman Empire, but the real rulers were the archbishops of Vienne. Their rights were repeatedly recognized, but they had serious local rivals in the counts of Albon, and later Dauphins of the neighboring countship of the Viennois. In 1349, the reigning Dauphin sold his rights to the Dauphiné to France, but the archbishop stood firm and Vienne was not included in this sale. The archbishops finally surrendered their territorial powers to France in 1449.[3] Gui de Bourgogne, who was archbishop 1090–1119, was pope from 1119 to 1124 as Callixtus II.

The Council of Vienne was the fifteenth Ecumenical Council of the Roman Catholic Church that met between 1311 and 1312 in Vienne. Its principal act was to withdraw papal support for the Knights Templar[3] on the instigation of Philip IV of France.

France

The archbishops did not give up their rights over it to France till 1449, when it first became French. Vienne was sacked in 1562 by the Protestants under the baron des Adrets, and was held for the Ligue 1590–95, when it was taken in the name of Henri IV by Montmorency. The fortifications were demolished between 1589 and 1636.[3]

Industrial era

Train stations were built in Vienne in 1855 and in Estressin in 1875 providing freight transport to the textile and metallurgy industries, which had begun taking advantage of the water power in the Gère Valley in the previous centuries.[8]

Monuments

The two outstanding Roman remains in Vienne are the temple of Augustus and Livia, and the Plan de l'Aiguille or Pyramide, a truncated pyramid resting on a portico with four arches, which was associated with the city's Roman circus.

The early Romanesque church of Saint Peter belonged to an ancient Benedictine abbey and was rebuilt in the ninth century, with tall square piers and two ranges of windows in the tall aisles and a notable porch. It is one of France's oldest Christian buildings dating from the 5th century laid-out in the form of a basilica and having a large and well constructed nave. It also boasts a beautiful Romanesque tower and a magnificently sculptured South portal containing a splendid statue of Saint Peter. Today, the building houses a lapidary museum that holds a Junon head and the beautiful statue of Tutela, the city's protective divinity.

The Gothic former cathedral of St Maurice was built between 1052 and 1533. It is a basilica, with three aisles and an apse, but no ambulatory or transepts. It is 315 feet (96 m) in length, 118 feet (36 m) wide and 89 feet (27 m) in height. The most striking portion is the west front, which rises majestically from a terrace overhanging the Rhône. Its sculptural decoration was badly damaged by the Protestants in 1562 during the Wars of Religion.[3]

The Romanesque church of St André en Bas was the church of a second Benedictine monastery, and became the chapel of the earlier kings of Provence. It was rebuilt in 1152, in the later Romanesque style.[3]

Gallery

- The SNCF Station of Vienne

The Gallo-Roman theater of Vienne

The Gallo-Roman theater of Vienne Pipet cemetery, Chemin des Aqueducs (D41), Notre Dame de Pipet

Pipet cemetery, Chemin des Aqueducs (D41), Notre Dame de Pipet Notre Dame de Pipet

Notre Dame de Pipet- Saint-André le Bas Abbey

- Saint-André le Bas Abbey

- Saint-André le Haut Abbey

- The #5 line, train station to Lucien Hussel hospital.

_022.jpg) The Gallo-Roman Pyramid

The Gallo-Roman Pyramid.jpg) Legend of the pyramid as Pontius Pilate's tomb

Legend of the pyramid as Pontius Pilate's tomb Fountain in central Vienne

Fountain in central Vienne.jpg) The banks of the river Rhône, in central Vienne

The banks of the river Rhône, in central Vienne_008.jpg) View over the North of the city

View over the North of the city- View over the South of the city with the Pilat mounts in the background

Famous residents

- Herod Archelaus (23 BC–c.18 AD), ethnarch.

- Pontius Pilate (according to legend)[6]

- Sextus Alcimus Ecdicius Avitus (St. Avitus) (450-c.578)

- Boso of Provence, (c. 841 - 11 January 887), Carolingian king of Provence.[9]

- Pope Callixtus II (1065-1124), pope.

- Michael Servetus (1509-1553), savant, burned as a heretic.

- Nicolas Chorier (1612-1692), lawyer, historian, author.

- Laurent Mourguet (1769-1884), puppeteer.

- Lucien Hussel (1889-1967), mayor & deputy.

- Fernand Point (1897-1955), chef.

Twin towns - sister cities

Vienne is twinned with:[10]

.svg.png)

See also

- Archbishopric of Vienne

- Council of Vienne (1311–1312)

References

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Flavius Josephus. "Book 17". Antiquities of the Jews. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

-

- Josephus, Wars of the Jews (book 2, chapter 7, verse 3).

- Constantin Zuckerman, 'Sur la liste de Verone et la province de Grande Armenie, la division de l'empire et la date de création des dioceses, 2002 Travaux et Memoires 12 Mélanges Gilbert Dagron, pp. 618-637 argues for a decision to create diocese by Constantine and Licinius at the meeting in Milan in February 313; since 1980 several scholars have suggested later dates (303, 305, 306, 313/14) than the traditional date of 297 set by Mommsen in the late 19th century

- Jacques Berlioz (1990). "Crochet de fer et puits à tempêtes: La légende de Ponce Pilate à Vienne (Isère) et au mont Pilat au XIIIe siècle". Le Monde Alpin et Rhodanien (in French): 85–104.

- André Pelletier (1966). "Les fouilles du "temple de cybèle" à Vienne (Isère) rapport provisoire". Revue Archéologique (in French). Presses Universitaires de France (1): 113–150. JSTOR 41005435.

- "Quartier d'Estressin, Vienne". Art et Histoire en Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (in French). Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Franz Staab (1998). "Jugement moral et propagande: Boson de Vienne vu par les élites du royaume de l'Est". In Régine Le Jen (ed.). La royauté et les les élites dans l'Europe carolingienne (du début du IXe aux environs de 920) (in French). L'institut de recherches historiques du Septentrion.

- "Les jumelages". vienne.fr (in French). Vienne. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

External links

- Livius.org: Roman Vienne - historical information and pictures

- Official website (in French)

- ‘Little Pompeii’ Unearthed in France is Most Exceptional Roman Site Found in Half a Century

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vienne (Isère). |