Kafr Saba

Kafr Saba (Arabic: كفر سابا) was a Palestinian Arab village famous for its shrine dating to the Mamluk period and for a history stretching back for more than a millennium.[6][7] The village was depopulated of its Arab residents by Jewish forces on May 13, 1948, one day before the new State of Israel was declared.[8][9]

Kafr Saba كفر سابا | |

|---|---|

Village | |

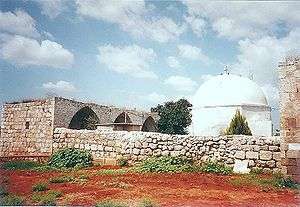

Mausoleum of Nabi Yamin, with riwaq (prayer hall) to the left. | |

| Etymology: the village of Sâba (from Aramaic )[1] | |

Kafr Saba | |

| Coordinates: 32°10′52″N 34°56′14″E | |

| Palestine grid | 144/176 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Tulkarm |

| Date of depopulation | 15 May 1948[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,688 dunams (9.688 km2 or 3.741 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 1,270[4][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Hak'ramim,[5] Beit Berl, Kfar Saba, Neve Yamin |

Presently the remains of the villages consists of two domed shrines located on either side of Route 55 between Kfar Saba and Qalqiliyya. The larger of the two is called Nabi Yamin, situated on the east side. About 40 meters (44 yd) away, on the west side of the road, is a much smaller shrine named Nabi Serakha.[10] The Nabi Yamin shrine was later taken over by a Haredi Jewish sect.

History

The origins of the name are not known – in Hebrew and Aramaic it means 'grandfather village'.

Antiquity

Kfar Saba (ancient Capharsaba) was an important settlement during the Second Temple period in ancient Judea,[11] and is mentioned for the first time in the writings of Josephus, in his account of the attempt of Alexander Jannaeus to halt an invasion from the North led by Antiochus (Antiquities, book 13, chapter 15). Kfar Saba appears in the Talmud in connection to corn tithing and the Capharsaba sycamore fig tree. Kfar Saba is mentioned in the Mosaic of Rehob, the oldest known Talmudic text, which dates from around the 3rd century C.E.

Excavations on the site have revealed the remains of a large Roman bathhouse. In the Byzantine periods the ruins of the bathhouse were first converted into fish pools, and later into some form of industrial installation.[12] Around year 985 C.E. Al-Muqaddasi described the place as a large village with a mosque that was situated on the road to Damascus.[13][14] In 1047 Nasir-i-Khusraw described it as a town on the road to al-Ramla, rich in fig and olive trees.[13]

A five-line inscription recording the grave of Sayf al-Din Bari, dated 1299–1300 CE was recorded within the shrine enclosure in 1922. The present location of this inscription is unknown.[15] A sabil ("water fountain") is situated on the east side of the main enclosure. An inscription embedded on the right side of this sabil referred to the foundation of a fountain for the public by Emir Tankiz, governor of Damascus in 1311–1312 CE.[16]

Ottoman era

In 1596, Kafr Saba was part of the Ottoman Empire, nahiya (subdistrict) of Bani Sa'b under the liwa' ("district") of Nablus. It had a population of 42 household; an estimated 231 persons, who were all Muslims. The villagers paid a fixed tax-rate of 33,3 % on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, goats and beehives, in addition to occasional revenues; a total of 8,314 Akçe. 3/24 the revenue went to a Waqf.[17]

In 1730, the Egyptian Sufi traveller al-Luqaymi visited Kafr Saba and saw the shrine for a local religious figure, Binyamin (also called al-Nabi Yamin).[13] In 1808 CE, the riwaq (prayer hall) was constructed, according to a now vanished inscription. This riwaq occupies the south side of the main enclosure of the shrine.[18] In the late nineteenth century, the village of Kafr Saba was described as a village built of stone and adobe brick and was situated on a low hill. It contained a mosque and was surrounded by sandy ground, with olive groves to the north. Its population was estimated to be 800.[19]

Part of the village was sold to the ICA during the Ottoman period. Jewish immigrants to Palestine established a moshava on the land and called it Kfar Saba.[20]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census there were 546 villagers, all Muslim,[21] increasing in the 1931 census to a population of 765, still all Muslims, in a total of 169 houses.[22]

The village expanded in the British Mandate period; new houses were built along the highway, and new agricultural land were cultivated to the west of the village.[13] In the 1945 statistics it had population of 1,270 Muslims,[4] while the total land area was 9,688 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[3] Of this, 1,026 dunums were used for citrus and bananas, 4,600 dunums for cereals, while 355 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards, of which 30 dunums were planted with olive trees.[23]

1948 War and aftermath

In the months leading up to the 1948 war, the local militia from Kafr Saba had attacked the neighboring Jewish town of Kfar Saba several times. The Arab Liberation Army (ALA), an army consisting of volunteers from several neighboring Arab countries, supported the Kafr Saba militia with troops during these intermittent attacks.[24] According to historian Benny Morris:

"By the beginning of May 1948, few Arabs were left in the Coastal Plain. On May 9, 1948 the Alexandroni Arab affairs expert, in preparation for the declaration of Israeli statehood and the expected pan-Arab invasion, ... decided to immediately 'expel or subdue' the inhabitants of the villages of Kafr Saba, al Tira, Qaqun, Qalansuwa, and Tantura. ... [O]n 13 May Alexandroni units took Kafr Saba, prompting a mass evacuation. ... The local Syrian ALA commander stood at the exit and to the village and extorted P£5 from each evacuee. Nine old men and women ... were left in the village and were later expelled.[9]

The Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi, described the remaining structures on the village land in 1992:

"The village site has been used for the construction of new residential quarters within an industrial area that is part of the settlement of Kefar Sava. Some of the old village houses have survived destruction and are located today within the settlement; a number of them are used as commercial buildings. The two shrines, the school, and the ruins of the village cemetery remain. The shrines have arched entrances and are surmounted with domes. The land around the site is cultivated by Israelis."[25]

After the war, the Nabi Yamin shrine near the town was abandoned. After 1967, the ruin was taken over by an ultraorthodox Jewish sect, that claimed it was the tomb of Benjamin, father of one of the 12 tribes of Israel.[26] Meron Benvenisti writes in 2002 that, "the dedicated inscriptions from the Mamluk period remain engraved on the stone walls of the tomb, but the cloths embroidered with verses from the Qur'an, with which the gravestones were draped, have been replaced by draperies bearing verses from the Hebrew Bible."[27] Benvenisti frames this transformation, and others similar to it, in the context of, "a wholesale appropriation of the sacred sites of a defeated religious community by members of the victorious one."[28]

The Jewish town of Kfar Saba, founded in 1903, was situated southwest of the village on the eve of the war. Following the war, it expanded to cover much of the village land. The location of the village is now the Shikun Kaplan area of modern Kfar Saba. Beit Berl, established in 1947 northwest of the village site, is on village land. The moshav of Neve Yamin was established in 1949 to the east of the village site on land around the shrine for al-Nabi Yamin. The Kibbutz of Nir Eliyahu was established in 1950 about 1 kilometer (0.62 mi) northeast of the village site, on lands of nearby Qalqilyah.[25]

References

- Palmer, 1881, p. 174

- Morris, 2004, p. xviii, village #193, Also gives the cause for depopulation

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 75

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 21

- Morris, 2004, p. xxii: settlement #106, 1949.

- Masalha 2007, p. 69

- Waked, Ali (2005-05-15), Palestinians mark ‘catastrophe’, ynet, retrieved 2009-08-13

- Benvenisti, 2002, p. 273

- Morris, 2004, pp. 246-247

- Petersen, 2001, pp. 233, 235

- Vilnai, Ze'ev (1976). "Kefar-Sava". Ariel Encyclopedia (in Hebrew). Volume 4. Israel: Am Oved. pp. 3790–96.

- According to Ayalon, 1982. Cited in Petersen, 2002, p.233

- Khalidi, 1992, p. 555.

- Al-Muqaddasi cited in Le Strange, 1890, p. 471

- Petersen, 2001, p. 235

- Mayer, 1933, pp. 219-220, cited in Petersen, 2001, p. 235

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 140. Quoted in Khalidi, p. 555

- Petersen, 2001, p. 234

- Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 134. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 555

- Karlinsky and Greenwood, 2009, pp. 158–159

- Barron, 1923, Table IX, Sub-district of Tulkarem, p. 28

- Mills, 1932, p. 57

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 126. Also cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.555

- Morris, 2008, p.164

- Khalidi, 1992, p.556.

- "Nabi Yamin" at The Seven Wonders of Israel. Also Zeev Vilnay, Saintly Tombs of the Land of Israel (1985, Achi-ever Press, Israel), V.I, p. 182. Also Gideon Bar (2008), "Reconstructing the Past: The Creation of Jewish Sacred Space in the State of Israel, 1948–1967", Israel Studies, 13 (3): 1–21, doi:10.2979/ISR.2008.13.3.1.

- Benvenisti, 2002, p. 277

- Benvenisti, 2002, p. 276

Bibliography

- Ayalon, E. (1982), "Kefar Sava -Nabi Yamin (Tomb of Benjamin)", ESI (Excavations and Surveys in Israel. (English version of Hadashot Arkheologiyot)), 1 p. 63. (Cited in Petersen, 2001)

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benveniśtî, M. (2000). Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948 (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21154-5.

- Birman, Galit (2006-06-11). "Kefar Sava (East)" (118). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Buchennino, Aviva (2010-05-23). "Kefar Sava, En-Nabi Gamin" (122). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Gorzalczany, Amir (2005-04-07). "Kefar Saba" (117). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karlinsky, Nahum and Naftali Greenwood. "California dreaming: ideology ...." Google Books. 10 August 2009.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Masalha, N. (2007). The Bible and Zionism: invented traditions, archaeology and post-colonialism in Palestine-Israel. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-761-9.

- Mayer, L.A. (1933). Saracenic Heraldry: A Survey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- ---- (2008), 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War, Yale University Press

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- al-Qawuqji, F. (1972): Memoirs of al-Qawuqji, Fauzi in Journal of Palestine Studies

- "Memoirs, 1948, Part I" in 1, no. 4 (Sum. 72): 27–58., dpf-file, downloadable

- "Memoirs, 1948, Part II" in 2, no. 1 (Aut. 72): 3–33., dpf-file, downloadable

- Wilson, C.W., ed. (c. 1881). Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt. 3. New York: D. Appleton. (p.116)

External links

- Welcome to Kafr Saba Palestine Remembered

- Kafr Saba, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 10: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Kafr Saba, at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center